Patient Management Exercise: Psychopharmacology: Treatment-Resistant Disorders

Abstract

This exercise is designed to test your comprehension of material presented in this issue of FOCUS as well as your ability to evaluate, diagnose, and manage clinical problems. Answer the questions below, to the best of your ability, on the information provided, making your decisions as you would with a real-life patient.

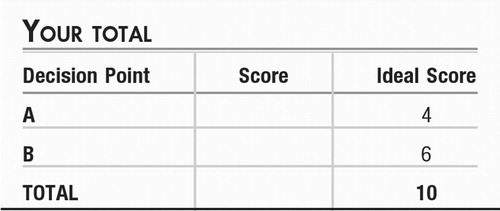

Questions are presented at “decision points” that follow a section that gives information about the case. One or more choices may be correct for each question; make your choices on the basis of your clinical knowledge and the history provided. Read all of the options for each question before making any selections. You are given points on a graded scale for the best possible answer(s), and points are deducted for answers that would result in a poor outcome or delay your arriving at the right answer. Answers that have little or no impact receive zero points. At the end of the exercise, you will add up your points to obtain a total score.

CASE VIGNETTE PART 1

The management of patients who are not able to recover with the initial treatment poses challenges in management, a phenomenon that cuts across virtually all psychiatric disorders.

Kevin W. is a 25-year-old man who initially had experienced disorganized behavior and paranoia at age 19 in the context of daily marijuana use while at college. He had transitioned from sporadically smoking marijuana to daily use when he moved away from home to a large university. He had become distressed by academic difficulties and suspicious feelings about some other students in a particular fraternity. He sought care at the college clinic, and after initially being told by the intake counsellor that he was probably “stressed out” by the demands of college and that he should stop smoking marijuana, he joined a student 12-step program and was able to stop his use of that drug. He performed poorly on his courses that term but did not fail out of the college. Nonetheless, the disorganization continued to adversely affect his academic performance in the next semester, and his situation came to the attention of the dean of students. With reevaluation by a psychiatrist at the college health program at that time, he was given the diagnosis of schizophrenia and was offered treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) agent at a dose within the therapeutic range. Over the ensuing month, he had some improvement in his paranoia ideation but had persistence of disorganization. Unable to succeed in his college coursework, he elected to take an extended leave of absence and moved back home with his parents.

He refused to see a psychiatrist in his hometown upon his return, but his parents were able to persuade him to be followed by his family doctor, who initially continued his treatment with the same SGA that had been prescribed at the college. After 2 months without change in symptoms, a trial of a second SGA, at a dose at the high end of the therapeutic range for that drug, was initiated. This controlled the paranoid ideation, but the patient was still too disorganized to take classes at a local community college or even to work part time in a local grocery store. Around this time the patient became frustrated with weight gain and sexual dysfunction and stopped his medication.

He rapidly became increasingly paranoid and disorganized and now was experiencing auditory hallucinations as well. The voices directed him to leave home and he wandered away from his parents' residence. He was found 2 weeks later in a park about 100 miles away, when he was picked up by the police in that town for vagrancy; because of his disorganized and confused behavior and his generally disheveled and malnourished state, he was taken to a regional hospital for involuntary hospitalization rather than to a holding cell at the jail.

After being evaluated in the emergency room there, he was admitted to the psychiatric inpatient service, and his parents were contacted for collateral history, because the patient was much too disorganized to be a reliable historian. Because he had failed to have a full response to two different SGAs, he was started on haloperidol, 10 mg at bedtime. His behavior and thought processes appeared to be less catastrophically disorganized within the first few days of hospitalization, and at that time he agreed to sign in for voluntary care. He continued to take his medications and was discharged back to home on hospital day 8. When he was seen by his family doctor 6 weeks later, he had evidence of improvement in paranoia but still had some prominent auditory hallucinations and disorganization.

At this point, he was willing to see an outpatient psychiatrist and was referred to you for evaluation and care. According to the International Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project (IPAP), he has treatment-refractory schizophrenia (1) with

| a. | nonresponse to at least two trials of antipsychotic medications from different classes, | ||||

| b. | moderate to severe psychopathology, especially positive symptomatology (conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, delusions, or hallucinatory behavior), and | ||||

| c. | no period of good functioning in the previous 5 years. | ||||

Consideration Point A:

As you review his records and your examination of this patient, some of the options you may consider as a next step in treatment include the following:

| A1._____ | Treatment with a third Second-Generation Antipsychotic agent (SGA). |

| A2._____ | Initiation of social skills training. |

| A3._____ | Treatment with clozapine. |

| A4._____ | Addition of methylphenidate to help him focus his attention. |

CASE VIGNETTE PART 2

Now under your care, the patient agreed to a trial of clozapine. The dose was titrated, and blood monitoring was instituted, and after 3 months of use, he experienced near-complete resolution of disorganization, hallucinations, and paranoia. He reported that, although he was clearly happy at last not to have these symptoms, he was having difficulty in his efforts to date because of the excess salivation and weight gain, side effects which both you and he ascribed to clozapine.

Social skills training was introduced. With this, Kevin was able to start working part-time at a local merchant and to take one class at the local community college. He reported that he had expanded his circle of friends.

After 2 months, his parents reported that he had become increasingly paranoid again. You saw him in your office, and your examination confirmed that he appeared to have had a return of paranoid ideation, with concerns mostly focused on police, the CIA, and other authority or law-enforcement figures.

Consideration Point B:

What source(s) of data would you consider collecting at this point?

| B1._____ | Obtain blood for a serum clozapine level to assess adherence. |

| B2._____ | Obtain Rorschach projective testing to assess level of psychosis. |

| B3._____ | Obtain urine for toxicology assessment. |

ANSWERS: SCORING, RELATIVE WEIGHTS, AND COMMENTS

Consideration Point A:

| A1._____ | Trial of yet another SGA. (−1) According to the IPAP (1), nonresponse to prior treatment with two chemically distinct SGAs suggests that a third SGA agent is not likely to lead to a response. |

| A2._____ | Social skills training. (+1) Social skills training can be a useful component of the overall treatment plan to help improve the functional outcomes of patients with psychotic illness (2, 3), although it is often more effective in patients who are less symptomatic. |

| A3._____ | Trial of clozapine. (+3) The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) manual suggests that clozapine should be considered at this point or even earlier (4). |

| A4._____ | Addition of methylphenidate. (−2) Although this agent may improve cognition and behavior in individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or may have some use with inattention in other syndromes, it has been found to have the potential to induce psychotic symptoms (5). |

Consideration Point B:

| B1._____ | Evaluation of biological evidence for nonadherence. (+3) Not adhering to treatment in the face of side effects may be more common than generally recognized and may lead to return of symptoms (6). |

| B2._____ | Projective testing. (0) Rorschach testing may be used to detect psychotic phenomena for diagnosis but has not found wide use in assessing degree of symptomatology or in following changes over time (7). A structured instrument, such as the PANSS (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale) or BPRS (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale), may be more useful in systematically monitoring symptom presence and severity serially. |

| B3._____ | Urine drug testing. (+3) Covert substance use, particularly of marijuana or of cocaine, may affect treatment outcome (8, 9). This patient has a past history of daily marijuana use. |

|

CONCLUSIONS

You determined that Kevin's urine showed evidence of marijuana and cocaine use. His blood level of clozapine was found to be low. In discussion with him, you learned that, as he developed a larger circle of friends, he had gravitated to associate with those who also had used marijuana, and now with money from his job and access to drug dealers, he had returned to daily marijuana use. He also had become introduced to cocaine use through his “friends.” With his attention increasingly devoted to substances of abuse, he had neglected to take clozapine as directed. He voiced despair at having relapsed with drugs of abuse and in disappointing his parents and you.

A family meeting was convened, and treatment options were reviewed. The patient and his family agreed with your recommendation for a brief inpatient detox program, to be followed by a dual-diagnosis program at a residential treatment center. He was able to follow through on your plan and while in the residential program was able to incorporate daily exercise into his life to address the weight gain he had associated with medication use. He was able to achieve symptom control with the reintroduction of clozapine.

After 4 months, he was discharged and went to live with his parents who had moved to a new town. In this new environment, he was able to maintain his abstinence, attend classes as a part-time student at a local college, and work part-time in a local business. He was able to use clozapine effectively as a component of his total treatment plan, which also included a 12-step program, a specialized cognitive behavior therapy program (10), and a clubhouse program (11).

1 The International Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project, 2009. http://www.ipap.org/schiz/Google Scholar

2 Halford WK, Harrison C, Kalyansundaram, Moutrey C, Simpson S: Preliminary results from a psychoeducational program to rehabilitate chronic patients. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:1189–1191Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Zarate R: Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32(Suppl 1):S12–S23Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Moore TA, Buchanan RW, Buckley PF, Chiles JA, Conley RR, Crismon ML, Essock SM, Finnerty M, Marder SR, Miller del D, McEvoy JP, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Shon SP, Stroup TS, Miller AL: The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2006 update. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:1751–1762Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Klein-Schwartz W: Abuse and toxicity of methylphenidate. Curr Opin Pediat 2002; 14:219–223Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Xiang YQ, Zhang ZJ, Weng YZ, Zhai YM, Li WB, Cai ZJ, Tan QR, Wang CY: Serum concentrations of clozapine and norclozapine in the prediction of relapse of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2006; 83:201–210Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Frank G: Research on the clinical usefulness of the Rorschach: 1. The diagnosis of schizophrenia. Percept Mot Skills 1990; 71:573–578Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Compton MT, Kelley ME, Ramsay CE, Pringle M, Goulding SM, Esterberg ML, Stewart T, Walker EF: Association of pre-onset cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco use with age at onset of prodrome and age at onset of psychosis in first-episode patients. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:1251–1257Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Shaner A, Khalsa ME, Roberts L, Wilkins J, Anglin D, Hsieh SC: Unrecognized cocaine use among schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:758–762Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Rathod S, Kingdon D, Weiden P, Turkington D: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication-resistant schizophrenia: a review. J Psychiatr Pract 2008; 14:22–33Crossref, Google Scholar

11 McGurk SR, Schiano D, Mueser KT, Wolfe R: Implementation of the thinking skills for work program in a psychosocial clubhouse. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2010; 33:190–199Crossref, Google Scholar