Advances in the Management of Treatment-Resistant Anxiety Disorders

Abstract

Anxiety disorders are among the most common and disabling mental illnesses. While effective treatments exist, many patients—possibly even 50–60%—remain symptomatic despite first-line treatments. With the exception of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), there are generally no universal definitions of treatment resistance and many treatments (both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic) have not been tested specifically in refractory cases. This article reviews the evidence for possible medication, psychotherapy, brain stimulation, and neurosurgical approaches—including some promising novel treatments—for managing treatment-resistant anxiety.

Anxiety disorders are among the most common and disabling of mental disorders, making them a serious public health concern (1). Anxiety disorders are associated with an increase in physician visits and medical costs and with reduced productivity at home and in the workplace (2). Although many pharmacological (and nonpharmacological) treatments exist, the evidence suggests that these disorders in many patients—perhaps as many as 50%–60%—are resistant or refractory to first-line treatments (3). This scenario speaks to the compelling need for recommendations about managing such patients.

There are two main challenges limiting clinicians who aim to provide evidence-based care for treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. The first is a general lack of agreed-upon definitions as to what constitutes treatment resistance in anxiety. In broad terms, our starting point in discussing treatment-resistant anxiety will be when a patient has not responded to one of two first-line treatments, for example, a serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The second challenge is that few studies have tested strategies in treatment-refractory cases. Unless otherwise noted, the investigations reported here were not tested after other treatments had failed. Given this lack of specific data, the majority of this article is a review of first-line efficacy studies. Although not ideal, this is the best evidence currently available that holds potential utility for treatment planning after first-line treatments have been unsuccessful. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is the only exception; as discussed in the section on Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, there are agreed-upon definitions of treatment resistance, and strategies have been tested in patients with treatment-resistant OCD. An additional limitation of the literature present for any disorder is publication bias; positive findings are more likely to be published than negative results.

When facing a patient who appears to have a treatment-refractory disorder, a critical first step is to ensure that the patient has received adequate first-line treatment. For example, many patients considered to have a treatment-resistant disorder have not yet received cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), which is a valid first-line therapy, and once they do receive such therapy respond well to it. Unfortunately, access to good-quality CBT is limited in many practice settings, although computerized and Web-based delivery approaches are increasingly being investigated to increase the reach of CBT (e.g., reference 4). Assessing adherence to treatment is also useful to confirm that patients have actually received an adequate trial of therapy and/or medication before moving on to therapies with a less well-established evidence base. Another essential step is to reevaluate a patient with a treatment-refractory disorder diagnostically to ensure that the principal diagnosis is correct and to ensure that there are not additional comorbid disorders that would require a different treatment strategy.

We refer all readers to the up-to-date APA Practice Guideline for Panic Disorder (5) and Guideline (6) and more recent Guideline Watch (7) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as the 2007 Guideline for OCD (8), which are all excellent resources on evidence-based practice for both initial treatment and treatment in refractory cases. The 2008 World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety and obsessive and post-traumatic stress disorders is another excellent review of evidence-based pharmacotherapy (9). Consultation with a psychiatrist experienced in treating anxiety disorders is also recommended when one is establishing a plan of care after first-line treatments have failed. At the end of each section, we include a case vignette example demonstrating possible approaches. Readers should note that in this review, we generally do not discuss mechanisms of actions or adverse effects of these medications and advise readers to be familiar with these before using the medication in clinical practice. In addition, reviewing the evidence for complementary or alternative treatments is beyond the scope of this review.

PANIC DISORDER

First-line treatment for panic disorder includes any of the following: SSRI, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (venlafaxine is the most studied, but duloxetine has a similar mechanism of action), tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) (the most data are available for imipramine or clomipramine; TCAs often are not used as first-line treatment because of their side effect profile), benzodiazepine (not adequate monotherapy if there is a co-occurring mood disorder), or CBT (5).

If one first-line treatment has failed or been inadequate, augmentation with or switching to another first-line therapy is recommended. As with other disorders, augmentation is generally preferable if a patient has had a partial response, whereas switching to another agent will probably be more efficacious if there has been no response. Examples of augmentation strategies include adding CBT or a benzodiazepine to an SSRI or adding an SSRI to CBT. A common reasonable switching strategy is to cross-titrate from an SSRI that has been completely ineffective to another SSRI, to an SNRI, or, less commonly, to a TCA. Only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) (N=46) has systematically studied a series of interventions in patients with panic disorder who failed to achieve remission with initial SSRI monotherapy (10). Simon et al. (10) noted that 21% of patients achieved remission after 6 weeks of initial SSRI monotherapy. Among those who did not achieve remission, increasing the dose of the SSRI in the next phase of the study was not effective. In the third phase of the study, remission rates were similarly low in both groups; CBT added to the SSRI was comparable to clonazepam added to the SSRI. Two open, noncontrolled studies found CBT to be effective after failed pharmacotherapy (11, 12).

Although there is little evidence specifically addressing the question of whether therapy is effective after failure with an SSRI, examining the more substantial data on using medication in combination with therapy as initial treatment may be informative in guiding treatment planning for the patient with a refractory disorder. An RCT of 150 patients with panic disorder found that the combination of CBT and an SSRI or SSRI alone was somewhat superior to CBT alone at the end of treatment, but this difference was no longer significant 6 and 12 months after treatment discontinuation (13). A 2006 meta-analysis of 21 RCTs of antidepressants and psychotherapy (mostly behavior therapy or CBT) for panic disorder concluded that in the initial phase of treatment, the combination of an antidepressant plus psychotherapy was better than either alone. In later phases of treatment, combination therapy remained more effective than antidepressants alone but was no better than psychotherapy alone (14). A recent meta-analysis of the three RCTs that studied combining benzodiazepines with psychotherapy reported that there was inadequate evidence to draw any definitive conclusions, but all studies found no advantage for combination treatment over monotherapy (15).

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Although there is evidence supporting their use in panic disorder, given their many potential adverse effects, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) should generally be reserved for situations in which several first-line treatments have failed. Phenelzine has proven effective for what would now be called panic disorder in one open (16) and two double-blind placebo-controlled studies (17, 18). Most studies of MAOIs were done before the publication of DSM-III and therefore did not use the panic disorder diagnosis; however, the description of symptoms is consistent with panic disorder. Doses found effective in those studies were fairly low, usually up to 45 mg/day. It is possible that higher doses may be needed for patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder, but no trials specifically address this question.

The reversible MAOIs are appealing, given that they do not typically require adherence to a low-tyramine diet or a 2-week washout period before starting. However, the studies examining moclobemide (which is not currently available in the United States) for panic disorder have yielded mixed results: two studies showed positive results, finding it comparable to fluoxetine (19) and clomipramine (20), whereas one showed benefit only for seriously ill patients (21), and another found no benefit over placebo (22). Brofaromine is a reversible MAOI that also inhibits serotonin reuptake. It is not available for use but has been found in three RCTs to be more effective than placebo (23) and as effective as fluvoxamine (24) or clomipramine (25). There have been no published studies of selegiline for panic disorder. None of the studies of MAOIs or reversible MAOIs were specifically conducted with treatment-resistant patients, so it is not known how effective they would be in patients for whom an SSRI, benzodiazepine, or CBT has failed.

Other antidepressants

As with MAOIs, the data on other antidepressants for panic disorder are limited to populations with nontreatment-refractory disorders. The evidence in support of mirtazapine for panic disorder includes three open-label studies (26–28) and one small (N=27) double-blind trial showing that mirtazapine was comparable in efficacy to fluoxetine (29). Although three small open trials found nefazodone to be potentially beneficial for panic disorder (30–32), no RCTs have confirmed this finding, and its use is limited by the risk of liver toxicity. In one very small (N=11) single-blind trial, trazodone was efficacious for panic disorder (33), but two larger RCTs found it ineffective in enhancing CBT (34) and less effective than imipramine or alprazolam (35). There is insufficient evidence to either support or refute the efficacy of bupropion in panic disorder; it was found to be effective in one small open trial (36) but not in another (37).

Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsants have been investigated for panic disorder in small studies, only two of which were RCTs. In one RCT, gabapentin was efficacious in the severely ill group, but there was no overall difference between gabapentin and placebo (38). Valproate was found to be effective in a very small open study (N=13) among patients with panic disorder and mood instability who had not responded to CBT and a first-line medication (39). Two other very small open-label studies also support the use of valproate for panic disorder, but these findings require confirmation in larger RCTs before it can be recommended, particularly given its significant side effects. Positive results in two case series of tiagabine (40, 41), suggested it could be beneficial for patients with treatment-refractory disorders. However, a subsequent open trial (42) and an RCT (43) found no difference between tiagabine and placebo. One small (N=14) controlled study found that carbamazepine was statistically, but not clinically, more effective than placebo (44). Positive results in one case series (N=3) of vigabatrin (45) and one (N=28) open-label study of levetiracetam (46) suggested that further study of these agents in controlled trials is warranted.

Antipsychotics

No evidence supports the use of first-generation antipsychotics in panic disorder. There is only preliminary positive evidence for some second-generation antipsychotics. Two open-label studies have examined olanzapine monotherapy (47) and olanzapine augmentation after a failed SSRI trial (48) with positive results. Risperidone augmentation appeared to be effective for panic disorder that had not responded to an SSRI and/or benzodiazepine in a small 8-week open-label study (N=30) (49). A more recent randomized, rater-blinded trial (N=56) found risperidone monotherapy equivalent to paroxetine (50). An open-label study of patients with refractory panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) found that aripiprazole augmentation of an SSRI and/or benzodiazepine significantly reduced anxiety (51). The only data on ziprasidone for refractory panic disorder is a small case series with positive results (52). Given the significant risk of metabolic side effects and the lack of conclusive evidence about their efficacy, second-generation antipsychotics cannot be widely recommended as second-line agents in panic disorder, but they could have utility in severe refractory cases.

Other medications

The evidence points to buspirone monotherapy being ineffective for panic disorder. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials have found buspirone to be comparable to placebo and less effective than imipramine (N=52) (53) and alprazolam (N=92) (54). Another RCT (N=60) detected no difference between buspirone, imipramine, or placebo groups (55), which the authors attributed in part to a strong placebo response. A small (N=16) randomized study concluded that clorazepate was significantly more effective than buspirone (56). Another RCT (N=91) found that buspirone did not enhance the efficacy of CBT for panic attacks, although there was an initial benefit at 16 weeks for agoraphobia and generalized anxiety that did not persist (57). Because buspirone is more commonly used clinically as an adjunctive agent than as monotherapy, controlled trials investigating its efficacy in conjunction with first-line agents in refractory cases would be valuable.

d-Cycloserine is a partial agonist of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor that has been shown to enhance extinction learning (58). A recent RCT lends strong preliminary support for adding d-cycloserine to exposure-based CBT for panic disorder (59). Although d-cycloserine requires further study, particularly in patients in whom first-line treatments have failed, it holds promise in enhancing CBT.

Antihypertensives

There is little evidence on the use of antihypertensives for panic disorder and even less data on their use in treatment-resistant disorders. One RCT of 25 patients with treatment-refractory disorders that showed positive results supports use of pindolol to augment fluoxetine (60), but these data have not been replicated.

Other psychotherapies

There is substantial evidence to support use of CBT, either in individual or group format, as a first-line treatment in panic disorder (5), but there is little evidence to guide the choice of alternative psychotherapies in a patient in whom CBT has not worked or in a patient who prefers another type of therapy. A manualized psychoanalytic psychotherapy called panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy was shown to be more effective than applied relaxation training in an RCT of 49 patients with panic disorder (61). Forms of psychodynamic psychotherapy other than panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy have not been tested in controlled trials. Emotion-focused therapy, a supportive psychotherapy, was found to be less effective than imipramine and CBT and comparable to placebo for panic disorder (62). In general, beyond the use of CBT, the evidence is sparse and essentially nonexistent for treatment-resistant cases.

Other treatments

There have not been any controlled investigations of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for refractory panic disorder. Although most commonly performed for refractory OCD, capsulotomy, the neurosurgical technique of producing bilateral lesions in the anterior limb of the internal capsule, has rarely been performed for severe treatment-refractory panic disorder. In their case series of 26 patients with refractory panic disorder (N=8), GAD, or social phobia, Rück et al. (63) reported significant 1-year and long-term reductions in anxiety but also noted that seven patients had substantial adverse side effects, most commonly frontal lobe dysfunction. More recently, deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been investigated for refractory OCD, but it has not been tested in panic disorder. At this time, psychosurgical approaches to treatment-refractory panic disorder cannot be advocated based on the evidence.

CASE VIGNETTE

A 23-year-old female college student with panic disorder with agoraphobia has been taking sertraline at 200 mg/day (the highest tolerable dose for her) for 8 weeks. She reports a significant decrease in the frequency and intensity of panic attacks but continues to avoid many activities because of fear of attacks and continues to have difficulty falling asleep because of fear of night-time panic attacks. You add a low dose (0.25 mg) of clonazepam twice daily. Her sleep improves, but she reports excessive daytime sleepiness and feels cognitively dulled and continues to have problems with avoidance. In addition, she expresses the desire to minimize the use of medication. You refer her for CBT, continue the SSRI at the present dose, and reduce the clonazepam to only one 0.25-mg dose at bedtime. After 12 weeks of CBT, there has been a further significant reduction in the number and intensity of attacks, and she has resumed many of the activities she previously avoided. She finds she needs the clonazepam only a few nights a week. After 20 weeks, her panic disorder is in remission, she continues to practice the techniques learned in CBT, and she no longer needs the clonazepam. You develop a treatment plan with her to continue the SSRI for another 6 months until summer break, at which time you successfully taper her off it, with the help of booster CBT sessions.

GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER

First-line treatment options for GAD include SSRIs, SNRIs, benzodiazepines (not adequate monotherapy for GAD with comorbid depression), buspirone, and CBT. As in panic disorder, if monotherapy with one of these agents is not successful, a reasonable next step is to either 1) augment the first agent (usually chosen if there was a partial response to the first treatment) or 2) switch to another first-line treatment (64).

Only one study has examined whether a different first-line treatment for GAD is effective after a first has failed. Schneier et al. (63) examined whether open-label escitalopram was beneficial for persistent symptoms of generalized anxiety after at least 12 sessions of CBT (65). Eight of the original 24 participants entering the study had clinically significant symptoms after 12 weeks of treatment. Four of those eight subsequently completed 12 weeks of open-label escitalopram treatment. Among those four, there was a statistical trend toward pre to post improvement on the primary outcome measure. Although these results are suggestive of a possible benefit, larger controlled trials are needed before any conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy of SSRIs for residual symptoms after CBT. There have not yet been any studies addressing the question of whether CBT is effective for persistent symptoms after SSRI or SNRI treatment. Likewise, studies are needed to examine whether SNRIs are effective after a failed SSRI trial and vice versa.

Other antidepressants

There is a general paucity of data, including even efficacy studies in treatment-naive patients, on use of other antidepressants for GAD. There has been only one double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a TCA for GAD. In their 8-week RCT (N=230) comparing imipramine, trazodone, and diazepam, Rickels et al. (66) found all three medications superior to placebo. Although diazepam worked most quickly, imipramine showed comparable, and on one measure even superior, efficacy by the study's end. That trial is also the only investigation of trazodone, which was also found to be slightly more efficacious than diazepam at 8 weeks. There have been no RCTs of MAOIs or reversible MAOIs among patients with GAD. One small (N=24) double-blind, randomized trial found bupropion XL comparable to escitalopram in anxiolytic efficacy, but there have not yet been any larger controlled confirmatory studies. Mirtazapine (67) and nefazodone (68) have shown promise for GAD in open trials, but larger RCTs are needed. None of these antidepressants have been systematically tested in treatment-refractory GAD. Overall the scant available first-line efficacy evidence supports imipramine and trazodone.

Antihypertensives

Antihypertensives have received little study for GAD, and neither of the two published trials focused on patients with treatment-refractory GAD. The one published RCT of β-blockers (N=49) for generalized anxiety found both propranolol and atenolol to be significantly more efficacious than placebo for patients awaiting therapy, but atenolol produced more intolerable cardiovascular side effects leading to more study dropouts (69). A double-blind crossover trial of clonidine (N=23) for patients with GAD or panic disorder found that it was it modestly superior to placebo for anxiety (70).

Antihistamines

Two controlled trials, neither of which was in treatment-refractory cases, support the use of hydroxyzine for GAD. In their RCT comparing hydroxyzine, bromazepam, and placebo (N=334), Llorca et al. (71) found that hydroxyzine was superior to placebo and comparable to the benzodiazepine. Lader et al. (72) studied hydroxyzine, buspirone, and placebo among 244 patients with GAD. Only hydroxyzine, but not buspirone, was superior to placebo on the primary outcome measure, the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, but on secondary measures both hydroxyzine and buspirone were superior to placebo.

Anticonvulsants

Pregabalin is an anticonvulsant approved for treatment of GAD in Europe but not in the United States. It is marketed in the United States with indications for various types of chronic pain. Six published double-blind RCTs have established the efficacy of pregabalin for GAD (73–78). All of these trials found pregabalin to be superior to placebo. In the four studies that also included an active comparative agent, the efficacy of pregabalin was similar to that of a benzodiazepine (73, 74, 76) and venlafaxine (77). Although most of the trials were short-term, the one that examined continuation treatment with pregabalin found it superior to placebo in preventing recurrence of symptoms (78). A meta-analysis of the six RCTs found that pregabalin was effective for both psychic and somatic anxiety in a dose-dependent relationship that reached a plateau at 300 mg daily (79).

The data for other anticonvulsants are less robust. There have been no RCTs examining gabapentin, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, or vigabatrin for GAD. In the one published double-blind RCT of valproate for GAD (N=80, all males), significantly more patients in the valproate group responded compared with the placebo group (80), but more controlled trials are needed, particularly given the side effect profile of valproate. Although one open-label study of tiagabine compared with paroxetine was promising (81), three parallel-group double-blind RCTs did not find it superior to placebo (82).

Therefore, pregabalin is currently the only anticonvulsant with sufficient efficacy data to warrant considering its use for refractory GAD. Notably, however, none of the investigations of pregabalin focused specifically on patients with treatment-refractory GAD, so it remains unknown how efficacious pregabalin would be as an adjunct or stand-alone treatment among patients in whom a first-line treatment has failed.

Antipsychotics

Of the typical antipsychotics, trifluoperazine carries an Food and Drug Administration indication for short-term treatment of nonpsychotic anxiety based on a 4-week RCT (N=415) that found trifluoperazine (2–6 mg daily) to be superior to placebo for moderate to severe GAD (based on DSM-III criteria) (83). This evidence must be weighed, however, against the significant risk of tardive dyskinesia with typical antipsychotics, particularly with longer-term use. In addition, that trial was not focused on treatment-refractory GAD.

The evidence for atypical antipsychotics is currently primarily limited to augmentation trials. However, many have been conducted in patients who have treatment-refractory GAD. Pollack et al. (84) studied olanzapine compared with placebo added to fluoxetine among 24 participants in an RCT who remained symptomatic after 6 weeks of fluoxetine. Olanzapine augmentation led to significantly more responders, but not remitters, compared with placebo, but the olanzapine group also gained significantly more weight (84). The data for risperidone are mixed. One RCT (N=40) of risperidone augmentation for persistent GAD symptoms after at least 4 weeks of anxiolytic treatment showed a significant reduction in symptoms compared with placebo, but response rates were not statistically significantly different (85). A larger (N=417) RCT of adjunctive risperidone among patients with GAD who were symptomatic after 8 weeks of anxiolytic treatment found no overall difference between risperidone and placebo, but among those participants with moderate to severe symptoms, risperidone did outperform placebo in symptom reduction (86). Although an open-label study of quetiapine augmentation in 40 patients with treatment-refractory GAD suggested that it could be beneficial, an RCT (N=70) of adjunctive quetiapine for patients remaining symptomatic after 10 weeks of paroxetine CR monotherapy failed to find quetiapine better than placebo (87). However a recent large (N=873) RCT testing quetiapine XR monotherapy compared with paroxetine or placebo found 150 mg daily of quetiapine XR or paroxetine to be equally efficacious in producing remission at 8 weeks, with the suggestion that quetiapine XR might work faster (88). Although the results are encouraging, it should be noted this trial was not in patients with treatment-refractory GAD. Two small open-label trials of aripiprazole augmentation for treatment-resistant GAD reported a significant reduction in symptoms (51, 89), but these preliminary data require confirmation in larger controlled investigations. Ziprasidone monotherapy or augmentation was studied in an RCT of 62 patients with refractory GAD and was not found to be superior to placebo (90).

Other medications

Riluzole is a glutamate modulator used in the treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. One small open-label trial (N=18) of riluzole for GAD found that it significantly reduced anxiety symptoms and led to a 67% response and 44% remission rate at 8 weeks (91). Larger controlled investigations are needed, however, particularly given the high cost of riluzole.

d-Cycloserine has not yet been studied in human clinical trials as therapy augmentation for GAD. Two novel agents, agomelatine (a melatonin agonist and serotonin 5-HT2C antagonist) (92) and deramciclane (a serotonin 5-HT2A/2C antagonist) (93) have shown promise for GAD in RCTs in patients with nontreatment-refractory disorders.

Other psychotherapies

Although CBT has the smallest average effect size for GAD compared with the effect sizes for other anxiety disorders (94), it and applied relaxation therapy have the largest evidence bases in support of them compared with other therapies in GAD (95). Given the smaller effect sizes and the fact that some patients might prefer other styles of therapy, it is worth examining the evidence for other therapies. There have not been any studies of other therapies after nonresponse to CBT. One RCT of 57 patients with GAD supports short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP) as being equally effective as CBT on the primary outcome measure (96); however, for secondary outcome measures including trait anxiety and worry, CBT was superior. In a randomized trial (N=326) of solution focused therapy, STPP, and long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (LTPP) for long-standing (>1 year) depressive or anxiety disorders, STPP was initially superior to LTPP for anxiety disorders (examined collectively), but at the 3-year follow-up LTPP showed better outcomes (97). It should be noted that there was no CBT or relaxation therapy comparison included, and the anxiety disorders were not examined individually. An 11-participant open trial of mindfulness meditation-based cognitive therapy produced promising results, suggesting that further study in controlled trials would be worthwhile (98). Similarly, a treatment called integrative therapy that incorporates CBT and interpersonal emotional processing therapy was effective in an open study of 18 patients with GAD. Overall, the existing data most strongly support CBT or applied relaxation.

Other treatments

ECT has not been tested for refractory GAD. A preliminary open trial of rTMS, a noninvasive technique, suggests that it could be a beneficial treatment for treatment-resistant GAD (99), but further controlled trials are needed. There are no published human trials of DBS in GAD. In the only published case series of capsulotomy for GAD (N=13 patients with GAD), Rück et al. (63) reported significant 1-year and long-term reductions in anxiety, but also noted that seven patients had substantial adverse side effects, most commonly frontal lobe dysfunction. Therefore, neurosurgical techniques cannot be recommended, even for severe treatment-refractory GAD.

Case vignette

A 55-year-old male veteran with GAD and major depressive disorder and a history of alcohol abuse (in full, sustained remission) has not responded to 40 mg/day of paroxetine (at which dose he is experiencing a lot of sedation) after 8 weeks. You switch to fluoxetine and gradually increase the dose to 60 mg/day, which he tolerates well, and after 8 weeks at that dose he joins a CBT group. He reports feeling so anxious that he has difficulty concentrating in the group and continues to have difficulty sleeping at night. You add trazodone, which helps his sleep, but he continues to have significant daytime anxiety and low energy and motivation. You continue the trazodone, but switch the fluoxetine to venlafaxine XR 75 mg mg/day and gradually increase the dose to 225 mg/day. After 8 weeks at 225 mg/day, he has had significant improvement in depressive and worry symptoms and finds he is more able to use the CBT successfully.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Exposure-based cognitive behavior psychotherapies [including prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR)] have a robust evidence base in support of their efficacy for PTSD, and there is wide consensus that they are first-line treatments (6, 7). The 2004 APA Practice Guideline for PTSD recommend SSRIs as first-line pharmacotherapy. However, since then, a 2007 Institute of Medicine review (100) concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the first-line use of SSRIs in PTSD because of the moderate effect sizes (approximately 0.5) from most RCTs. In addition, the 2009 APA Guideline Watch for PTSD (7) concluded there has been a decrease in the strength of evidence for SSRIs in the treatment of combat-related PTSD based on mixed results from recent trials of SSRIs in that specific population. While we await evidence to resolve these questions, given the relatively favorable side effect profile of SSRIs, as well as multiple RCTs (6, 7) and meta-analyses (101, 102) in support of their use, SSRIs continue to be a reasonable first-line pharmacotherapy choice for many patients. Another first-line choice is an SNRI, in particular venlafaxine, for which there are multiple RCTs supporting its efficacy in PTSD (103, 104).

Few studies have specifically looked at what to do when one first-line treatment has failed. Simon et al. (105) tested whether paroxetine CR added onto prolonged exposure therapy was helpful for participants who remained symptomatic after eight individual prolonged exposure therapy sessions. They did not find that paroxetine CR was any better than placebo, but this result could have been due to the fairly small sample size (N=23). A randomized trial of sertraline alone versus sertraline with culturally tailored CBT among 10 Cambodian female refugees with PTSD who had not achieved remission with an antidepressant found the combination treatment highly efficacious (106), suggesting that adding CBT to an antidepressant is a reasonable next step option. Although there is little evidence to guide next-step treatment choices, as with the other disorders, a reasonable first step after failure of one first-line agent is to augment with or switch to another first-line agent.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Two 8-week trials support the efficacy of amitriptyline for PTSD. In their RCT of 46 combat veterans, Davidson et al. (107) found that amitriptyline was superior to placebo but noted low overall remission rates (only 36% of amitriptyline and 28% of placebo groups were in remission by the end of the study). A head-to-head randomized comparison of amitriptyline (75 mg/day) and fluoxetine (60 mg/day) in 20 Bosnian combat veterans showed that both produced a significant reduction in symptoms (70% for amitriptyline and 60% for fluoxetine) (108). Two RCTs of imipramine and phenelzine found both medications to be superior to placebo for PTSD (109, 110), although one noted a small advantage for phenelzine over imipramine (110). In contrast, desipramine was not found to be efficacious for PTSD, although this result could be due to the small sample (N=18) and short duration (4 weeks) of the crossover RCT (111). Notably, none of the tricyclic antidepressant studies were performed specifically in treatment-resistant populations and most participants were male combat veterans, limiting the potential generalizability of these findings.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

The two RCTs of imipramine and phenelzine described above provide evidence in support of the efficacy of phenelzine in PTSD (109, 110). Another small (N=13) double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study failed to find a difference between phenelzine and placebo after 4 weeks (112). Regarding the reversible MAOIs, only open-label studies suggest the efficacy of moclobemide for PTSD (113, 114), and the RCTs of brofaromine yielded mixed results (115, 116).

Other antidepressants

The only RCT of mirtazapine for PTSD found it effective on some, but not all, measures of symptoms (117). Bupropion is not effective for PTSD as demonstrated in two RCTs (118, 119), although the primary focus of one trial was smoking cessation (119). Two RCTs of nefazodone support its use in PTSD (120, 121), and an open-label study of 19 veterans in whom three previous medication trials had failed (122) suggests that nefazodone may have a role in treatment-refractory PTSD, although its widespread clinical use is limited by potential hepatotoxicity. Although widely used as an augmenting agent for insomnia in PTSD (123, 124), trazodone has only been studied in one very small (N=6) open-label trial (125) and not in any controlled studies.

Antipsychotics

First-generation antipsychotics have not been investigated for PTSD in any published controlled trials. The evidence for second-generation atypical antipsychotics is largely limited to augmentation studies. Risperidone augmentation has been investigated in five controlled trials with mixed results. Three RCTs found that adjunctive risperidone was effective particularly for the reexperiencing and hyperarousal symptom clusters in combat veterans (126, 127) and in women who had experienced childhood abuse (128). However, the two other trials did not find risperidone augmentation beneficial for overall PTSD symptoms but did note improvement specifically for sleep (129, 130) and psychosis (130). The only RCT of adjunctive olanzapine among 19 patients with PTSD with only minimal response after 12 weeks of SSRI monotherapy demonstrated significant improvement in PTSD, sleep, and depression symptoms, but it led to a 13-pound mean weight gain (131). There have been two RCTs of atypical antipsychotics as monotherapy for PTSD. Risperidone was effective for the primary outcome, an overall measure of PTSD symptoms but not any secondary outcomes in a trial of 20 women who had experienced sexual assault or domestic violence (132). In a small RCT (N=15), olanzapine monotherapy was no better than placebo and caused significantly more weight gain, but there was a high placebo response rate (133). There have not been any RCTs of quetiapine, aripiprazole, or ziprasidone as augmentive or monotherapy for PTSD. Overall, atypical antipsychotics appear to be a promising but imperfect option for treatment-refractory PTSD.

Anticonvulsants

Overall, there have been few studies of anticonvulsants for PTSD, and they have yielded mixed to negative results. There are three studies with clearly negative results: one large multicenter RCT found no difference between tiagabine and placebo for PTSD (134) and two RCTs in veterans found valproate monotherapy to be ineffective (135, 136). In contrast, a small RCT (N=15) showed promising results for lamotrigine (137), but no larger follow-up studies have yet been published to confirm or refute this finding. Topiramate monotherapy was found to be effective in an RCT of civilian PTSD (138). However, augmentive topiramate was not effective in a trial of chronic PTSD in combat veterans, possibly because of a higher dropout rate in the topiramate group (139). Gabapentin has only been studied in one controlled 14-day trial (N=48), which compared it to propranolol and placebo in prevention of PTSD and found it to be ineffective in that setting (140). Pregabalin, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, tiagabine, and vigabatrin have not been tested in controlled trials in PTSD. Preliminary open studies of augmentive pregabalin (N=9) (141) and augmentive levetiracetam (N=23) (142) in nonresponders or partial responders to antidepressants suggest that these medications are worthy of further study in larger controlled trials of refractory PTSD.

Antihypertensives

Propranolol has been studied for the prevention of PTSD in two RCTs that involved administering it shortly after a traumatic event and then following patients over time, with generally negative results (140, 143). It has not been studied in chronic or treatment-refractory PTSD. Neither other β-blockers nor calcium channel blockers have been studied in controlled PTSD trials.

The α-adrenergic antagonist prazosin has received considerable recent study specifically for PTSD nightmares and sleep disturbance in patients with chronic, refractory PTSD. Although there was heterogeneity in the number and types of treatments patients had tried, all of participants had chronic PTSD and were already taking medications or were in therapy and could therefore be considered to have treatment-refractory PTSD. Three sequential trials (144–146) examining adjunctive prazosin in PTSD (added to whatever stable treatment participants were already receiving) found that it was not only effective for reducing nightmares and increasing sleep time but also helpful in reducing overall PTSD symptoms. Raskind et al. conducted a 20-week double-blind crossover study (N=10) (145) and a follow-up larger RCT (N=40) (144) of veterans with chronic PTSD and found that prazosin was effective for reducing trauma nightmares and improving sleep quality as well as overall clinical status. Mean daily doses (taken at bedtime) in those studies were 9.5 and 13 mg, respectively. Their third study was a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study that examined more specific sleep measures in addition to PTSD symptoms among 13 mostly female patients with chronic PTSD from civilian trauma (146). They found that in addition to reducing PTSD symptoms overall, prazosin (mean nightly dose 3 mg) also significantly increased total sleep time, REM sleep time, and mean REM duration.

Benzodiazepines

Somewhat surprisingly, only two very small RCTs have looked at benzodiazepines for established PTSD, with generally negative results. Braun et al. (147) conducted a very small double-blind crossover trial (N=10) and found that alprazolam was helpful only for nonspecific anxiety and ineffective for core posttraumatic symptoms and noted that it produced significant rebound anxiety. Another very small (N=6) randomized, single-blind (patient), placebo-controlled crossover trial found that clonazepam was ineffective for sleep disturbances, particularly nightmares (148). Clearly, more work is needed to evaluate the utility of benzodiazepines for PTSD, particularly treatment-resistant cases for which benzodiazepine augmentation may be useful.

Other pharmacotherapy

d-Cycloserine was investigated in one small (N=11 patients with chronic PTSD) double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in which it was found to be generally comparable to placebo (149). However, this study did not include psychotherapy, so it could not answer the question of whether d-cycloserine could enhance response to psychotherapy for patients with PTSD.

Other psychotherapies

Exposure-based CBTs are first-line psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD (6, 7). There have not been any studies testing other therapies for refractory PTSD after CBT has failed; therefore, we cannot answer the most salient question of whether the following therapies would work specifically in treatment-refractory PTSD. However, we review the evidence for them in patients with nontreatment-refractory PTSD, as it could be helpful in guiding treatment planning after first-line strategies have failed.

EMDR therapy incorporates exposure-based therapy with guided eye movements, recall, and verbalization of traumatic memories. Although many individual EMDR studies have been small, meta-analyses support the efficacy of EMDR for PTSD (150, 151). There have been conflicting results of meta-analyses comparing the efficacy of EMDR with that of CBT (152, 153). Given that EMDR includes a type of exposure therapy, the question of whether the eye movements are an essential feature of EMDR has been raised (154). A 1999 critical review (155) and a 2001 meta-analysis (152) found that the eye movements were neither necessary nor sufficient for efficacy of EMDR, but this finding is still being debated (156).

One controlled trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy (N=112) found it comparable to trauma desensitization and hypnotherapy and concluded that all three therapies were superior to a wait-list control (157, 158). A meta-analysis that included psychodynamic psychotherapy also supports its efficacy for PTSD (158). A more recent randomized trial of 32 veterans with chronic PTSD comparing hypnotherapy or zolpidem added to an SSRI and supportive therapy found hypnotherapy effective in reducing PTSD symptoms and as effective as zolpidem in number of hours of sleep but superior in improving sleep quality (159).

Other treatments

Although ECT has not been studied in controlled trials of PTSD, there have been recent promising results from studies of rTMS, particularly higher frequency right-sided rTMS. In their RCT of low-frequency (1 Hz) rTMS, high-frequency (10 Hz) TMS, and sham rTMS for 24 patients with PTSD, Cohen et al. (160) found that 10 daily treatments over 2 weeks of 10-Hz rTMS applied to the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) were superior to both low-frequency and sham TMS in producing a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms. In a recent RCT, Boggio et al. (161) compared 20-Hz rTMS applied to either the right or left DLPFC with sham rTMS. Similar to the study of Cohen et al., the treatments were administered in 10 daily sessions over 2 weeks. They found that both right and left DLPFC rTMS were effective in reducing PTSD symptoms, but right rTMS had a greater effect and led to additional improvements in mood and overall anxiety. These benefits persisted at the 3-month follow-up. Osuch et al. (161) examined in a sham-controlled crossover study whether 20 sessions of 1 Hz rTMS therapy delivered over 3–5 sessions per week could enhance prolonged exposure therapy among nine patients with chronic, treatment-refractory PTSD (162). Overall, they did not find a statistically significant difference between the sham and active treatment, but hyperarousal symptoms were more improved in the active group.

No neurosurgical techniques have been investigated for PTSD.

In summary, despite many cases of PTSD being resistant to existing treatments, very little available evidence exists to guide treatment decisions. Lacking this evidence, the available literature suggests that augmentation with atypical antipsychotics may be beneficial in some patients. Given its preliminary promising results, prazosin should be more formally studied in treatment-resistant PTSD algorithms.

Case vignette

A 45-year-old female business executive with PTSD from a rape in college was unable to tolerate one SSRI (escitalopram) because of initial activation and increase in anxiety. She has a history of alcohol abuse in full, sustained remission, so she asks to avoid any potentially addictive medications. You start a more sedating SSRI (paroxetine) at night, which she is better able to tolerate. After 4 weeks of a full dose, she reports improvement but continues to have poor sleep and nightmares. She declines CBT because of schedule constraints. You maximize the dose of the SSRI and add prazosin initially 1 mg at bedtime for a week. You gradually increase the prazosin 1 mg every 1–2 weeks, and once you reach 4 mg nightly, she reports a significant decrease in nightmares and improvement in her sleep. She also reports that her daytime concentration and irritability have improved and she feels less “on guard” and is better able to tolerate reminders of the rape.

OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER

First-line treatment for OCD includes CBT [specifically exposure and response prevention (ERP), at least 13–20 weekly sessions with daily homework] and/or an SSRI, typically at high doses for at least 8–12 weeks (8). Clomipramine is also highly effective for OCD, but it is generally recommended that an SSRI be tried first, given the more favorable side effect profile of SSRIs (8).

OCD is the only anxiety disorder for which there are generally agreed-upon definitions of nonresponse. In OCD trials, “nonresponders” are typically participants whose Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale (Y-BOCS) score has decreased 25% or less from baseline or who have been rated less than much improved on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale (163). These definitions are not, however, universally used, and considerable heterogeneity among nonresponders remains, leading experts in the field to call for more scientifically validated measures of response (163). In addition, many patients called responders remain symptomatic (8, 163).

If one first-line treatment has failed or has been inadequate, augmenting with or switching to another first-line therapy is recommended. As with other disorders, augmentation is generally preferable if a patient has had a partial response, whereas switching to another agent will probably be more efficacious if there has been no response. Examples of augmentation strategies include adding CBT to an SSRI or adding an SSRI to CBT. There is evidence, mostly open trials (164–166), but also two controlled trials (167, 168), in support of adding CBT after inadequate response to an SSRI. There have not been any trials examining whether an SSRI is effective either as monotherapy or augmenting treatment after nonresponse or a partial response to CBT. A common reasonable switching strategy is to cross-titrate from an SSRI that has been completely ineffective to another SSRI, clomipramine, or an SNRI (8). Surprisingly, few controlled studies specifically addressed the question of whether a second serotonergic antidepressant is effective after another failed. In one randomized, double-blind, crossover trial, 150 patients with OCD were randomly assigned to receive either paroxetine or venlafaxine ER. After 12 weeks, the 43 nonresponders were switched to the other agent for 12 weeks. The authors found that 42% of nonresponders benefited from switching to the other agent (169). Although venlafaxine ER and paroxetine were both initially comparably effective (170), in the latter part of the trial, paroxetine was superior to venlafaxine among nonresponders to the previous agent (169). Interestingly, a placebo-controlled trial of intravenous clomipramine found it effective for patients with OCD who had not responded to oral clomipramine (171), but the clinical use of intravenous clomipramine is limited by the need for cardiac monitoring.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

MAOIs have not been investigated for treatment-refractory OCD in controlled trials. The only published RCT of an MAOI as initial therapy for OCD generally found that phenelzine was ineffective and fluoxetine was effective, although the subgroup with symmetry obsessions did respond to phenelzine (172). The reversible MAOIs including moclobemide, brofaromine, and selegiline have not been investigated in controlled trials of OCD.

Other antidepressants

The other antidepressants have not been studied specifically for OCD that has not responded to first-line treatments. An initial treatment trial of 12 weeks of open-label mirtazapine followed by 8 weeks of double-blind placebo-controlled discontinuation found it to be effective for OCD (173), but additional RCTs have not yet been conducted. A single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial found that mirtazapine added to citalopram accelerated treatment response, but responder rates at the end of the trial were similar in the citalopram plus placebo and citalopram plus mirtazapine groups (174). There have not been any RCTs of nefazodone for OCD. A small open investigation of bupropion did not find it effective for OCD (175). The only RCT of trazodone for OCD found that it was ineffective for OCD (176).

Anticonvulsants

There have not been any controlled trials of anticonvulsant monotherapy either for initial treatment or treatment for nonresponders. The one randomized, but open-label study of gabapentin added onto fluoxetine suggested that it could accelerate the treatment response but did not lead to better outcomes at any time point after 2 weeks (177).

Antipsychotics

The vast majority of published RCTs of antipsychotics for OCD have studied adding an antipsychotic after insufficient response to an SSRI. The overall results have been mixed, with the exception of risperidone, for which results were generally positive. In an RCT, haloperidol added to fluvoxamine was effective for treatment-refractory OCD, but only among those patients with both OCD and tics (178). Randomized placebo-controlled trials of olanzapine and quetiapine augmentation have yielded mixed results. One RCT found that olanzapine augmentation was efficacious (179), whereas another found no difference compared with continuing monotherapy with an SSRI (180). Two RCTs with positive results support quetiapine augmentation (181, 182), but three RCTs with negative results did not find it effective (183–185). The two published RCTs comparing augmentive risperidone with placebo for refractory OCD found it efficacious (186, 187). A head-to-head, single-blind, randomized study comparing olanzapine to risperidone augmentation in SSRI nonresponders found that both medications were effective for OCD but found limited tolerability for both (due to amenorrhea with risperidone and weight gain with olanzapine) (188). Li et al. (189) studied risperidone and haloperidol in a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial and found them to be equally efficacious, but risperidone was superior for depressive symptoms and was better tolerated overall. Using these data, Bloch et al. (190) conducted a meta-analysis and concluded that atypical antipsychotics, particularly risperidone, could be useful for augmentation in treatment-refractory cases of OCD. They noted that the evidence was too mixed to conclusively either support or refute using olanzapine and quetiapine (190). Matsunaga et al. (191) conducted a 1-year study of antipsychotic augmentation for SSRI nonresponders (191). In that trial, 90 patients were initially treated with an SSRI for 12 weeks, followed by the addition of CBT for 1 year. Patients who had less than 10% reduction in OCD symptoms after 12 weeks of the SSRI (N=44) were also randomly assigned to receive olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone augmentation of the SSRI for 1 year in addition to CBT. The authors noted that although the SSRI nonresponders had a significant reduction in OCD symptoms, their initial and final Y-BOCS scores were higher than those of the SSRI responders, and they experienced significant side effects from the antipsychotic augmentation (191). One promising open-label investigation of aripiprazole augmentation for treatment-refractory OCD (192) suggests that it is worthy of further study in larger controlled trials.

Other medications

Benzodiazepines have received surprisingly little study for OCD, and there have not been any controlled trials in treatment-refractory cases. Clonazepam has been studied as an initial therapy with mixed results. Of the monotherapy studies, one found that it was effective (193), whereas another did not (194), and the one augmentation study found no difference with placebo (195). Although one small RCT (N=18) found that buspirone monotherapy was comparable to clomipramine for treatment-naive patients (196), when studied as an adjunctive agent for refractory OCD, its efficacy was not supported by the results of controlled trials (197–199). An open-label investigation of riluzole with positive results suggests that it could be worthy of further study (200). Lithium was not found to be an effective adjuvant treatment for refractory OCD in two small controlled trials (201, 202). One of those small studies also failed to find that triiodothyronine added onto clomipramine was helpful for clomipramine nonresponders (202). A small (N=23) randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study found that adding once-weekly morphine (30–45 mg) to SSRIs outperformed placebo among participants in whom two to six previous SSRI trials had failed (203), but further investigations are needed. Likewise, promising results of a single-blind case-control study of 44 patients with severe treatment-refractory OCD suggests that memantine is worthy of further study (204).

Two small double-blind placebo-controlled studies, one in chronic OCD (205), of single-dose dextroamphetamine (30 mg) found that it produced a significantly greater reduction in symptoms compared with placebo (205, 206). A more recent 5-week double-blind study (N=24) of dextroamphetamine (30 mg/day) or caffeine (300 mg/day) added to an SSRI/SNRI after nonresponse (207) found that both agents produced significant decreases in OCD symptoms.

Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of d-cycloserine added to CBT found that it enhanced response to CBT, particularly in the initial phases of treatment (208, 209). Neither of these studies was conducted specifically with a medication-resistant population, so it is still not clear whether d-cycloserine would be beneficial in treatment-refractory OCD.

Antihypertensives

Pindolol augmentation was found to be effective in one small RCT in treatment-refractory OCD (210), but it did not show benefit in augmenting the initial response to fluvoxamine in another small RCT in treatment-naive patients (211). The sole randomized double-blind study of clonidine in patients with nontreatment-refractory OCD found that it was ineffective (193).

Antihistamines

The same study that found clonidine ineffective for OCD also found that diphenhydramine produced a significant reduction in symptoms, although it was intended to be a nonactive comparator (193). However, this study was not in patients with treatment-refractory OCD, and there have not been any other studies of it. There have been no investigations of hydroxyzine in OCD.

Psychotherapy and other psychosocial treatments

CBT for OCD can focus primarily on behavioral techniques as in ERP therapy or primarily on cognitive techniques. ERP in a variety of different settings (individual, group, therapist guided, and patient-controlled) has been the most extensively studied and consistently has demonstrated efficacy for OCD, leading to its being a first-line treatment for OCD (8). No controlled trials studying other therapies after a failed trial of ERP have been conducted.

Although there have not been controlled trials, large open studies of both partial hospitalization (212, 213) and intensive residential treatment (214–218), including long-term follow-up after discharge (212, 217), suggest these are worthy of consideration for severe treatment-refractory OCD.

Other treatments

Various ablative neurosurgical techniques, including anterior capsulotomy, gamma-knife radiosurgery, and cingulotomy, have been tried for severe treatment-refractory OCD, but only in case reports and uncontrolled studies (219–224). Therefore, it is difficult to interpret the reported response rates of up to 50%. In addition, the potential adverse effects, including psychosis, seizures, personality change, hydrocephalus, and executive dysfunction, indicate that ablative neurosurgery should be reserved for only patients with severe OCD for whom multiple first- and second-line agents have failed (8). More recently, the less-invasive technique of DBS (in which electrodes connected to a stimulator are neurosurgically placed into the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule and ventral striatum) has shown promise in two small studies. A small (N=4) study of DBS that included a blinded on/off phase showed significant benefit during the blinded treatment in one participant and moderate benefit for another during open follow-up (225). More recently, Goodman et al. (226) conducted a sham stimulation-controlled study of six patients with severe treatment-refractory OCD and found that DBS led to a significant response in four participants after 12 months of stimulation.

The only evidence in support of ECT in treatment-refractory OCD is a case series of 32 patients (227). Therefore, although the case series reported generally positive results, given the risks of anesthesia and memory loss, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of ECT for OCD, although it may have utility when there are co-occurring conditions for which ECT is indicated, such as depression (8).

Recently rTMS, a noninvasive technique, has been investigated for a variety of psychiatric disorders including OCD. The early sham-controlled studies of rTMS for OCD used a low frequency (1 Hz) over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (228, 229) or right prefrontal cortex (230); none showed benefit for OCD symptoms. With use of those three studies, a recent meta-analysis (231) concluded that rTMS was ineffective for OCD. Consistent with those studies, a more recent sham-controlled trial of 10 sessions of high-frequency (10 Hz) rTMS over the right prefrontal cortex failed to find benefit for OCD symptoms but did note significant decreases in depression and overall anxiety symptoms (232). In contrast, two recent sham-controlled studies of low-frequency (1 Hz) rTMS to different brain regions, including the orbital frontal cortex (233) and bilateral supplementary motor area (234), showed significant benefit for OCD symptoms in patients with medication-resistant OCD, suggesting that larger trials of rTMS on these brain regions are warranted.

In summary, there have been more studies done for treatment-refractory OCD than for any other anxiety disorder. Although further investigations are needed, particularly for patients in whom multiple first- and second-line treatments have failed, there was sufficient evidence for the authors of the OCD APA Practice Guideline to outline a treatment algorithm (8).

Case vignette

A 33-year-old unemployed man with severe OCD who you see through a public mental health clinic had no appreciable improvement in symptoms after 10 weeks of citalopram 60 mg/day. You switch to another SSRI (fluoxetine) and titrate up to his maximally tolerated dose (80 mg/day). After 8 weeks, he reports a decrease in the intensity of obsessions and a slight decrease in time spent on compulsions but continues to have significant distress. CBT for OCD is not available in your community. You add low-dose risperidone augmentation (initially 0.5 mg at bedtime and then increase to 1 mg at bedtime after 1 week) and continue the high-dose SSRI. After another 4 weeks, he has had a significant reduction in symptoms but not enough that he has improved functionally (i.e., he still spends many hours per day performing compulsions). You increase the risperidone to 1 mg b.i.d., and within 2 weeks he notices that it is easier to distract himself from his obsessions and the time spent on compulsions has reduced enough that he is able to start searching for work.

SOCIAL PHOBIA

First-line therapy for social anxiety disorder, also called social phobia, includes SSRIs, the SNRI venlafaxine ER, and/or CBT (9, 235). Phenelzine is also effective for social anxiety disorder but given the more favorable side effect profile of SSRIs or venlafaxine ER, it is recommended that phenelzine be tried second-line (9). Clonazepam also has demonstrated efficacy for social phobia, but only for short-term treatment; therefore, it is typically best used as an addition to an SSRI or SNRI, either when starting the SSRI/SNRI to give initial symptom relief or in treatment-refractory cases (9).

As with the other anxiety disorders, if one first-line treatment has failed or been inadequate, augmenting with or switching to another first-line therapy is the recommended next step. If a patient has had a partial response, augmentation is typically recommended, whereas switching to another first-line agent will probably be more efficacious if there has been no response. Examples of augmentation strategies include adding CBT and/or clonazepam to an SSRI or adding an SSRI to CBT. Although there is little specific data to guide switching after SSRI nonresponse, most experts recommend switching from a failed SSRI to another SSRI, venlafaxine ER, or phenelzine (9).

There are no studies on augmenting CBT with medication or vice versa after monotherapy with either has failed. However, studies on combining medication and therapy for initial treatment of social anxiety disorder have been conducted with mixed results. Recently Blanco et al. (236) reported the results of their RCT (N=128) comparing phenelzine, cognitive behavior group therapy (CBGT), or their combination for initial treatment of social anxiety disorder. They found that combination treatment was most efficacious; in addition, phenelzine was superior to placebo but CBGT was not. In contrast, an RCT (N=295) of fluoxetine, CBGT, or their combination found that all treatments were superior to placebo by the end of the study, with no advantage for combination therapy (237). Therefore, although there is no specific evidence to guide second-step treatment choices after failure of one first-line agent, given the strong evidence base for SSRIs, venlafaxine, phenelzine, and CBT, switching to another of these agents or combining medication and CBT would be a reasonable next step. Extremely limited evidence exists on what to do for social anxiety disorder after two first-line treatments have failed. Therefore, in the following we review available evidence for other treatments, most of which is from nontreatment-refractory cases.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants

As described above, four RCTs support of the efficacy of phenelzine as an initial treatment for social anxiety disorder and, therefore, it should be considered in patients for whom a first-line treatment has failed (9). Multiple double-blind trials demonstrate the efficacy of the reversible MAOIs including moclobemide (238–242) and brofaromine (243–245) in nontreatment-refractory social anxiety disorder, although brofaromine is not currently available for use, and moclobemide is not currently approved for use in the United States. A small 6-week open-label study of low-dose oral selegiline (10 mg/d) suggested that it had modest efficacy for social phobia (246).

There are no controlled trials of TCAs for social anxiety disorder.

Other antidepressants

The data in support of mirtazapine are limited to one open trial with positive results (247) and one RCT with positive results among 66 women with social anxiety disorder (248); neither study was in patients with treatment-resistant disorders. The one RCT (N=105) of nefazodone found that it was ineffective for social phobia. Bupropion and trazodone have not been studied in controlled trials of social anxiety disorder.

Benzodiazepines

Clonazepam is the only benzodiazepine that has been studied in controlled trials for the treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clonazepam monotherapy has been shown to be more efficacious than placebo (249–251), including use for long-term treatment (249), and with efficacy comparable to that of CBT (252). One RCT of 28 patients with social anxiety disorder found clonazepam added to paroxetine to be more efficacious than paroxetine alone on some, but not all, outcome measures, although the authors noted that this result could be attributable to inadequate power (253). Although none of these investigations were in patients with treatment-refractory disorders, the first-line efficacy of clonazepam and the different mechanisms of action of benzodiazepines and SSRIs/SNRIs suggest there may be a role for adding clonazepam to an SSRI or SNRI after a partial response.

Anticonvulsants

None of the investigations of anticonvulsants have focused on patients with treatment-refractory social anxiety disorder. The most promising data for anticonvulsants in patients with nontreatment-refractory disorders are RCTs in support of gabapentin (N=69) (254) and high-dose (600 mg/day) but not low-dose (150 mg/day) pregabalin (N=135) (255). Although levetiracetam initially appeared promising in an open-label study (256), it was subsequently found to be ineffective for social anxiety disorder in two RCTs (257), one of which was large (N=217) (258). Open trials of tiagabine (259), topiramate (260), and valproic acid (261) as initial monotherapy for social anxiety disorder suggest that they are worthy of further study in controlled trials.

Antipsychotics

In the one investigation of antipsychotic augmentation for refractory social anxiety disorder, Simon et al. (49) studied open-label risperidone augmentation (N=7 participants with social anxiety disorder) of an SSRI or benzodiazepine that patients had not fully responded to after 8 previous weeks of treatment. Although the results were promising, further study in large, controlled trials is needed before this can be a recommended treatment. A small RCT (N=12) found that olanzapine monotherapy was superior to placebo in a population with nontreatment-refractory disorders (262). Whereas an open-label study (263) suggested a role for quetiapine monotherapy in social anxiety disorder, subsequent RCTs of monotherapy for generalized social anxiety (264) and of single-dose quetiapine before a public speaking virtual exposure (265) did not find benefit. Given the generally high side effect burden of these agents, further study is needed before they become part of standard treatment options for treatment-resistant social anxiety disorder.

Other medications

Although buspirone appeared to have some efficacy in open studies as monotherapy (266) and as an SSRI augmentation (267), two RCTs failed to find any benefit over placebo (268, 269) or any augmentive effect with CBT (268, 269) for social phobia. Riluzole has not been investigated in social anxiety disorder. One open-label trial with positive results in patients previously treated with antidepressants suggests that reboxetine (270) should be investigated in larger RCTs for refractory social phobia. A small RCT (N=27) of atomoxetine found that it was not effective for social anxiety disorder (271).

Antihypertensives

Although β-blockers may be useful for specific performance or test anxiety (272–275), they appear to be ineffective for generalized social anxiety disorder, including treatment-refractory cases. Pindolol augmentation of paroxetine was not found to be superior to placebo in a small (N=14) double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study among patients who had not responded to 10 previous weeks of paroxetine monotherapy (276). Atenolol was shown to be ineffective as initial monotherapy for social anxiety disorder in two randomized, controlled trials (276–278). The α-adrenergic antagonists have not been investigated for the treatment of social phobia.

Other pharmacotherapy

Diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine have not been investigated for social anxiety disorder.

The two randomized, placebo-controlled trials of d-cycloserine in social anxiety disorder found that it was efficacious in enhancing response to CBT (exposure therapy) (279, 280). Although these studies were not in patients with treatment-resistant disorders, they suggest that d-cycloserine is worthy of consideration for enhancing an exposure therapy trial in this population. The hormone, oxytocin, was also studied in an RCT (N=25) as a potential enhancer of exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder but was found to be ineffective (281).

Other psychotherapies

CBT, particularly exposure therapy but also cognitive therapy, has been shown to be effective for social phobia and is a first-line treatment (9). There have not been any controlled investigations of other therapies in patients in whom CBT has yielded a partial or nonresponse. Other psychotherapies, however, have shown utility for social anxiety in controlled trials and may be worthy of consideration if CBT has not been effective or if it is unavailable. Two recent controlled trials of a computerized attention training found it highly effective for social anxiety disorder (282, 283), although another controlled study did not find that attention training enhanced CBGT (284). One trial (N=58) found that psychodynamic group therapy and clonazepam were more effective than clonazepam alone for social anxiety disorder (285). Mindfulness-based stress reduction was found to be less effective than CBGT for generalized social anxiety disorder in a head-to-head randomized trial (286).

Other treatments

There are no reported trials or case series of ECT, rTMS, or DBS for social anxiety disorder. In their case series (N=26) of capsulotomy that included five patients with social phobia, Rück et al. (63) reported significant 1-year and long-term reductions in anxiety, but also noted that seven patients had substantial adverse side effects, most commonly frontal lobe dysfunction. Given this extremely limited evidence base and the substantial side effects, capsulotomy cannot be recommended even for the most treatment-refractory social phobia.

Case vignette

A 29-year-old male graduate student with generalized social phobia has not responded to 12 weeks of sertraline 150 mg/day (his maximally tolerated dose). You switch to escitalopram, which, after 8 weeks at 30 mg/day, yields only slight improvement in his self-consciousness and no change in his avoidance. You add CBT, which he finds very helpful, but he continues to have great difficulty in any group meetings, which he needs to attend for his program. You continue CBT, but, after a 2-week washout period and careful explanation of dietary and medication restrictions, switch the SRRI to phenelzine and gradually increase the dose to 60 mg/day. He gradually improves to the point of being able to more effectively use the skills learned in CBT when attending the group meetings. After practicing a public speaking exposure exercise in CBT, he is able to successfully present his work during a talk at a national meeting. His ability to interact with colleagues in less formal situations also improves, and he is able to make contacts for a future fellowship job.

SUMMARY

A paucity of data addresses the management of patients with treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. For most anxiety disorders, with the exception of OCD, there are no consistent definitions of treatment resistance in the literature, making it difficult to judge and compare the data that do exist across studies. These severe limitations notwithstanding, there is beginning to emerge both within and across disorders a literature on approaches to patients with treatment-resistant disorders. At the present time, the data cannot be considered compelling for any anxiety treatment-resistant indication, but clinicians are nonetheless frequently faced with anxiety treatment resistance, and so we present the following suggested approach based on what little published evidence is available, buttressed and expanded upon by our own clinical experience and by other published treatment recommendation guidelines (5–9).

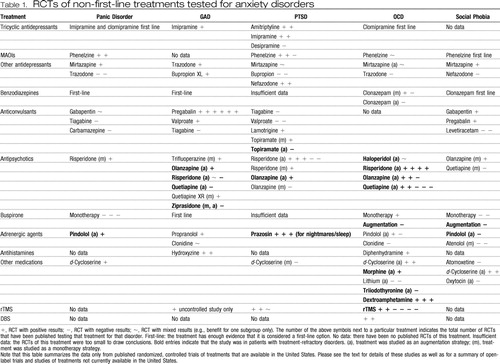

As described in the Introduction, this approach should be used only after thorough diagnostic assessment, evaluation of adequacy of prior treatment, and, ideally, consultation with colleagues experienced in treatment of refractory anxiety disorders. When faced with a patient with an anxiety disorder who remains symptomatic after an adequate trial of a first-line treatment, we recommend either switching to (in the case of nonresponse) or augmenting with (in the case of partial-response) another first-line treatment. If that is ineffective, we recommend successive complete trials of first-line agents (if any remain untried) or second-line agents (with augmentation if clinically indicated). In general, a complete medication trial would be 8–12 weeks at the highest tolerable dose. If a medication is effective, there are scant data to guide length of maintenance treatment; using good clinical judgment, taking into account patient preference and a risk/benefit assessment on a case-by-base basis, is advised. Although there is some variation by disorder, an adequate trial of CBT would typically consist of at least 12–20 sessions with the patient doing daily homework. If all first-line and second-line treatments have been exhausted or are clinically inappropriate, Table 1 presents the evidence for and against possible next-step strategies. Although large gaps remain in our knowledge of how best to manage treatment-refractory anxiety disorders, recent advances offer promise.

|

Table 1. RCTs of non-first-line treatments tested for anxiety disorders

1 Kessler RC, Wang PS, Kessler RC, Wang PS: The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health 2008; 29:115–129 Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Saarni SI, Suvisaari J, Sintonen H, Pirkola S, Koskinen S, Aromaa A, Lönnqvist J: Impact of psychiatric disorders on health-related quality of life: general population survey. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190:326–332. Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Ravindran LN, Stein MB: Anxiety disorders: somatic treatment, in Kaplan and Sadock Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009, pp 1906–1914. Google Scholar

4 Furmark T, Carlbring P, Hedman E, Sonnenstein A, Clevberger P, Bohman B, Eriksson A, Hållén A, Frykman M, Holmström A, Sparthan E, Tillfors M, Ihrfelt EN, Spak M, Eriksson A, Ekselius L, Andersson G: Guided and unguided self-help for social anxiety disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 195:440–447 Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Stein MB, Goin MK, Pollack MH, Roy-Byrne P, Sareen J, Simon NM: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. Alexandria, Va., American Psychiatric Association, 2009 Google Scholar

6 Ursano RJ, Bell C, Eth S, Friedman M, Norwood A, Pfefferbaum B, Pynoos RS, Zatzick DF, Benedek DM: Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Alexandria, Va., American Psychiatric Association, 2004 Google Scholar

7 Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatazick D, Ursano RJ: Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Alexandria, Va., American Psychiatric Association, 2009 Google Scholar

8 Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, Nestadt G, Simpson HB: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Arlington, Va., American Psychiatric Association, 2007 Google Scholar

9 Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, Kasper S, Möller HJ, WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disoders, Zohar J, Hollander E, Kasper S, Möller HJ, Bandelow B, Allgulander C, Ayuso-Gutierrez J, Baldwin DS, Buenvicius R, Cassano G, Fineberg N, Gabriels L, Hindmarch I, Kaiya H, Klein DF, Lader M, Lecrubier Y, Lépine JP, Liebowitz MR, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Marazziti D, Miguel EC, Oh KS, Preter M, Rupprecht R, Sato M, Starcevic V, Stein DJ, van Ameringen M, Vega J: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders—first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry 2008; 9:248–312 Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Simon NM, Otto MW, Worthington JJ, Hoge EA, Thompson EH, Lebeau RT, Moshier SJ, Zalta AK, Pollack MH. Next-step strategies for panic disorder refractory to initial pharmacotherapy: a 3-phase randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:1563–1570 Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Pollack MH, Otto MW, Kaspi SP, Hammerness PG, Rosenbaum JF: Cognitive behavior therapy for treatment-refractory panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:200–205 Google Scholar

12 Heldt E, Gus Manfro G, Kipper L, Blaya C, Isolan L, Otto MW: One-year follow-up of pharmacotherapy-resistant patients with panic disorder treated with cognitive-behavior therapy: outcome and predictors of remission. Behav Res Ther 2006; 44:657–665 Crossref, Google Scholar