Advances in the Management of Treatment-Resistant Depression

Abstract

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is a prevalent, disabling, and costly condition affecting 1%–4% of the U.S. population. Current approaches to managing TRD include medication augmentation (with lithium, thyroid hormone, buspirone, atypical antipsychotics, or various antidepressant medications), psychotherapy, and ECT. Advances in understanding the neurobiology of mood regulation and depression have led to a number of new potential approaches to managing TRD, including medications with novel mechanisms of action and focal brain stimulation techniques. This review will define and discuss the epidemiology of TRD, review the current approaches to its management, and then provide an overview of several developing interventions.

TREATMENT-RESISTANT DEPRESSION: DEFINITION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Major depressive disorder is a widespread and costly illness, with a 1-year U.S. prevalence of about 7% (1). A variety of antidepressant treatments are available, but many patients fail to achieve sustained symptomatic remission. Continued depressive symptoms are associated with ongoing functional impairment (2), increased usage of health care resources (3), a greater risk of suicide (4–6), and overall increased mortality, especially associated with cardiovascular disease (7–10).

Despite the growing recognition of the public health importance of treatment-resistant depression (TRD), a consensus definition for this condition does not exist. Various approaches to stages of treatment resistance have been developed, including the Thase-Rush (11), Massachusetts General Hospital (12), and Maudsley systems (13). It has been conservatively estimated that >10% of depressed patients will not respond to multiple, adequate interventions (including medications, psychotherapy, and ECT) (14), and data from a large, community-based sequential treatment study (STAR*D) suggest that up to 33% of patients may fail to achieve full symptomatic remission despite multiple medication attempts (15). Studies of TRD have varied widely in the operational criteria used, but failure of at least two antidepressant treatments (of adequate dose and duration) from two distinct classes is one of the most consistent definitions in the literature (16). This definition also has predictive validity. In STAR*D, remission rates with the first two treatments were quite similar (36.8% in the first level and 30.6% in the second) but decreased significantly after a failure of two treatments (13.7% in the third level and 13.0% in the fourth) (15).

Considering these various definitions of TRD, the estimated prevalence ranges from 10% to 60% of all depressed patients (12, 14, 15), resulting in a U.S. prevalence of about 1%–4%, equal to or greater than the prevalence of schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or Alzheimer's dementia. And, for those patients who do eventually respond after multiple treatments, relapse is quite high (up to 80%) (17–19), emphasizing the fact that better strategies are needed to both treat and prevent depressive episodes.

CURRENT APPROACHES FOR MANAGING TRD

Establishing the correct diagnosis

When a patient presents with TRD, the first step is to confirm the primary diagnosis, assess for the presence of psychiatric and medical comorbidity, and verify the adequacy of prior treatments through a careful patient interview (with collateral information if available) and review of medical records (20). More than 10% of patients with the initial diagnosis of major depression may ultimately meet the criteria for bipolar disorder (21) and may require a modified treatment approach. Psychiatric comorbidity is common in depression and TRD (primarily anxiety, personality, and substance use disorders) (22, 23), and failure to achieve remission may be associated with inadequate treatment of these other conditions. Similarly, certain comorbid medical illnesses (e.g., sleep apnea, anemia, thyroid disease, hypogonadism, and others), as well as nonpsychiatric medications (e.g., corticosteroids, interferon alfa, and chemotherapy), may be associated with symptoms and side effects that overlap with those of depression. Finally, many patients with depression labeled as “treatment-resistant” may not have actually achieved adequate doses of prior medications for a sufficient duration (12, 14), such that a first step in management often includes increasing and potentially maximizing dose and duration of a current or prior treatment.

Medication augmentation

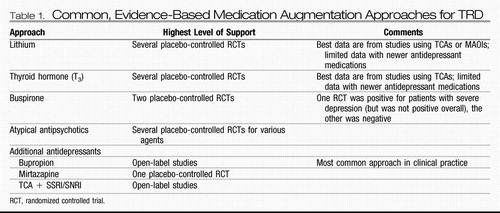

For patients with documented treatment resistance to one or more medications, augmentation is a typical approach. Accepted augmentation agents for TRD include lithium, thyroid hormone, buspirone, and atypical antipsychotics. Combining antidepressant medications is also quite common. Table 1 provides a summary of these approaches, including the highest level of support for each.

|

Table 1. Common, Evidence-Based Medication Augmentation Approaches for TRD

Lithium.

Lithium augmentation (typically at doses ≥600 mg/day) currently has the most extensive evidence base with reported response rates between 40% and 50% (in depression studies, response is typically defined as a decrease in depression severity of at least 50% compared with baseline) (24). However, it should be noted that the majority of these studies combined lithium with a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). The efficacy of lithium augmentation of newer antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), is less clear (25). It is notable that lithium probably acts in part through modulation of the serotonin neurotransmitter system (26), such that it may be less mechanistically distinct from many newer medications compared with the older agents. In STAR*D, lithium was added after two failed treatment attempts that included bupropion, citalopram plus bupropion, citalopram plus buspirone, sertraline, or venlafaxine (27). Lithium augmentation was compared with triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation (results for T3 are described below). Lithium augmentation was associated with a 16% remission rate and a 16% response rate; 23% of patients dropped out due to side effects.

Thyroid hormone.

Augmentation with 25–50 μg of T3 also has an extensive database in medication-refractory depression (again with most studies adding this agent to a TCA). One meta-analysis found mixed results but generally confirmed a statistically significant advantage for T3 augmentation of TCAs, with an overall response rate of 57% (a 23% improvement over placebo) (28). Another meta-analysis identified a statistically significant benefit for T3 in accelerating the response to TCAs (29). In STAR*D, patients were randomly assigned to augmentation with either T3 or lithium after two failed treatments (see above for details). T3 augmentation was associated with a 25% remission rate and a 23% response rate (response was defined using a different scale than that used to define remission; in addition, it is possible that some patients achieved remission without having a 50% decrease in depression severity because of a partial response in the previous STAR*D levels); 10% of patients dropped out due to side effects. The numerical advantage of T3 over lithium augmentation was not statistically significant.

Buspirone.

Buspirone augmentation (at doses ranging from 10 to 60 mg/day) has a mixed database supporting antidepressant efficacy (largely comprising open-label studies). One placebo-controlled trial (N=119) found no statistically significant benefit for buspirone augmentation in patients not responding to an SSRI (30). A second placebo-controlled trial (N=102) also found no overall augmentation benefit for buspirone but did identify statistically significantly greater antidepressant effects in patients with severe depression (31). Buspirone augmentation was used in the second level of STAR*D (for patients not achieving remission with citalopram) and compared with bupropion augmentation. Remission rates were virtually identical with the two agents (roughly 30%), although bupropion was associated with a greater reduction in self-rated depression severity and a lower dropout rate due to side effects.

Atypical antipsychotics.

Atypical antipsychotic medications have previously shown benefit as augmentation agents for a number of SSRI-resistant nonpsychotic anxiety disorders (32–36). A recent meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found that atypical antipsychotic augmentation of an antidepressant medication was associated with statistically significantly greater response and remission rates, with a pooled response rate of 44% compared with 30% for placebo (37). Discontinuation due to side effects was greater for the antipsychotics compared with placebo. Aripiprazole is currently U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of depression not responding to an SSRI or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). Quetiapine monotherapy and the combination agent olanzapine/fluoxetine have each received FDA approval for the treatment of bipolar depression.

Combining antidepressants.

The most common combination of antidepressants is the addition of bupropion to an SSRI or SNRI (38, 39), despite a limited database with no placebo-controlled studies (40). As described above, bupropion augmentation of citalopram had a remission rate similar to that of buspirone augmentation in STAR*D, although there was some evidence for greater antidepressant effectiveness of bupropion overall. The efficacy of adding mirtazapine to an SSRI/SNRI is supported by a small database including at least one placebo-controlled trial (41, 42). The combination of an SSRI/SNRI with a TCA is somewhat supported by a limited dataset (43–46).

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is a mainstay in the treatment of depression, and it is generally accepted that structured, evidence-based psychotherapies such as behavioral activation, cognitive behavior therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy are as effective as antidepressant medications, even in moderate and severe depression (47–50). These therapies may also be effective in medication-resistant depression (48, 51, 52). Short-term psychodynamic therapies have also shown benefit for depression (53–56). The combination of psychotherapy with an antidepressant medication may be more effective than medication alone (49, 54, 57). Finally, psychotherapy may help prevent relapse, possibly to a greater degree than continued pharmacotherapy (58, 59). One challenge in managing patients with psychotherapy is that efficacy probably correlates with therapist skill and expertise (50), and some patients may not have ready or affordable access to an appropriate psychotherapist.

ECT

ECT was introduced in 1938 as a treatment for “schizophrenia” (60), yet has proved to be the most effective acute treatment for a major depressive episode (61, 62), with remission rates of more than 40%, even in patients with TRD (63–65). The efficacy of ECT has been validated in a number of open and blinded controlled trials, including comparisons with medication, sham ECT, and transcranial magnetic stimulation (62, 66–68). Cognitive side effects, especially retrograde amnesia, are common with ECT, and may be persistent (61, 69, 70). In addition, despite its acute efficacy, depressive relapse after a successful ECT course is still common, even when continuation ECT (ECT treatments delivered at an increasing time interval beyond the acute course) or optimal medication management is used (18, 63). Despite these limitations, ECT remains the best validated acute treatment for a major depressive episode, even when standard medication and psychotherapeutic interventions have not been effective.

Ablative surgery

The first antidepressant medications were developed in the 1950s (71–73). Before this, treatments for patients with severe depression unresponsive to ECT were limited and often invasive [such as the prefrontal leucotomy (74)]. After the advent of pharmacotherapy for depression, neurosurgery remained an option for a small group of patients with severe and treatment-resistant depression, facilitated by the development of stereotactic neurosurgical techniques that allowed more focal ablation (75, 76). Ablative procedures in use today include capsulotomy (a lesion in the anterior limb of the internal capsule), cingulotomy (a lesion in the dorsal anterior cingulate), subcaudate tractotomy (a lesion in thalamocortical white matter tracts inferior to the anterior striatum), and limbic leucotomy (which combines a subcaudate tractotomy with a cingulotomy) (77). In TRD, the efficacy for these procedures in open-label, naturalistic studies has been judged to be between 22% and 75% (78, 79); side effects include epilepsy, cognitive abnormalities, and personality changes (78–80).

ADVANCES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF TRD

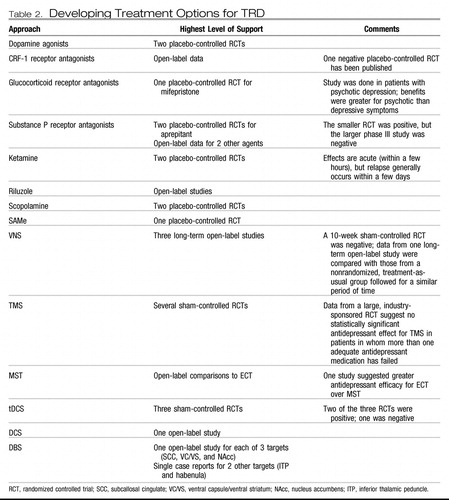

Two main approaches have defined the search for improved strategies for managing depression and TRD. The first has focused on development of novel medications. Although some of these continue to rely on modulation of monoaminergic neurotransmitter systems, the majority are based on targets in neuromodulatory systems beyond the monoamines. The second approach has focused on development and refinement of focal brain stimulation techniques, in which a focal electrical current is introduced in neural tissue with the goal of modulating activity locally and within a broader network of connected brain regions. This review will focus on medications and brain stimulation approaches for which published clinical data are available (see Table 2 for a summary).

|

Table 2. Developing Treatment Options for TRD

Novel pharmacological targets

Dopamine agonists.

Dopamine receptor agonists (pramipexole and ropinirole) are accepted treatments for Parkinson's disease (81). Data in TRD are limited, although two placebo-controlled trials in treatment-resistant bipolar depression (82, 83) and two open-label studies in treatment-resistant unipolar depression support potential efficacy (84, 85). A long-term (48-week) extension of an open-label study of pramipexole in unipolar TRD showed that 36% of patients achieving remission relapsed; the absence of a comparison group limits the interpretation of this finding (86). Larger, placebo-controlled trials of both pramipexole and ropinirole as augmentation agents in TRD have been initiated and/or completed (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov), but results have not been published.

Modulators of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function.

It is well-recognized that emotional or physical stress predisposes an individual to developing depression. Corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF), a neuropeptide produced in the hypothalamus and released after a stressful event to initiate the stress hormone cascade, has been implicated in the pathophysiology of depression, largely through its actions at the CRF-1 receptor (87–90). Several CRF-1 receptor antagonists possess anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects in animal models (88). However, the early clinical data on these agents are mixed (91, 92), although several agents are currently in phase II/III studies (93).

Another strategy for modulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis involves interfering with the synthesis or action of glucocorticoids. Several medications (e.g., ketoconazole, aminoglutethimide, and metyrapone) decrease cortisol synthesis and have demonstrated antidepressant effects, although poor tolerability has hampered use and further development of these agents (94). The glucocorticoid 2 receptor antagonist mifepristone has shown antidepressant efficacy for chronic depression in a single case series (95), and overall clinical efficacy for psychotic depression in one open (96) and one blinded placebo-controlled study (97). In the latter, effects were greater for psychotic than depressive symptoms.

Substance P (NK-1) antagonists.

Neurokinins are neuropeptides known to help mediate the neural processing of pain. The neurokinin substance P has been associated with the mammalian response to stressful stimuli (98, 99), and blocking its action can decrease the physiological and behavioral reactions to stress (100, 101). Substance P has also been implicated in the stress response in patients with major depression (102), and successful antidepressant treatment has been associated with decreased serum substance P levels (103). Agents that block a major substance P receptor (NK-1) have shown antidepressant-like effects in animal models. One NK-1 receptor antagonist, aprepitant, demonstrated antidepressant efficacy in a placebo-controlled study (100), but these results were not confirmed in a larger, phase III trial (104). Antidepressant effects have been seen with two other agents in early pilot studies (105, 106), but these findings await replication.

Glutamatergic modulation.

Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain that binds to both ionotropic [N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid, and kainate) and metabotropic (G protein-coupled) receptors. Glutamatergic function is implicated in the neurobiology of depression (107–110). NMDA antagonists have shown antidepressant-like properties in animal studies (111, 112). Amantadine, an orally administered NMDA receptor antagonist, has show antidepressant-like effects as an augmentation agent in preclinical and clinical studies (113).

More recently, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated very rapid (within a few hours) and significant antidepressant effects with a single intravenous infusion of ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant unipolar (114) and bipolar (115) depression. Unfortunately, these effects were time-limited, and depressive relapse occurred within days to weeks. An open-label study found that six repeated ketamine infusions were safe and generally well-tolerated in a group of 10 patients with TRD (116). Of the nine patients who received repeated infusions, all responded and eight achieved remission. One patient remained generally well for more than 3 months, but the other eight relapsed within 2 months (with a mean time to relapse of 19 days).

The antidepressant effects of ketamine may be mediated by a family history of alcoholism as suggested in an open-label study (117). Further, although memantine, an orally administered NMDA antagonist, did not have statistically significant antidepressant effects in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (118), it did show antidepressant effects equivalent to those of escitalopram in patients with major depression and alcohol dependence (119).

Riluzole is a medication with a complex and largely unknown mechanism of action that may involve inhibition of glutamate release. Open-label studies in treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression suggest antidepressant efficacy for riluzole (120–122). However, riluzole failed to prevent relapse after successful antidepressant treatment with ketamine (123).

Scopolamine.

Based on a database suggesting a role for the cholinergic system in the neurobiology of depression and antidepressant treatment, the antimuscarinic agent scopolamine was tested and demonstrated rapid (within days) antidepressant effects in a series of small, placebo-controlled trials (124, 125). No data on relapse were presented in these reports, so the duration of these effects is unknown.

S-Adenosylmethionine.

S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) is a molecule involved in the transfer of methyl groups across a variety of biological substrates. A number of controlled studies have demonstrated antidepressant effects for intravenous or intramuscular SAMe (126). A recent double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral SAMe augmentation in patients not responding to an SSRI showed statistically significant antidepressant effects (127).

Focal brain stimulation

The emergence of focal brain stimulation therapies over the past few decades has been jointly facilitated by major advances in neuroimaging and the technical ability to acutely and chronically stimulate a discrete neural target. Neuroimaging studies have helped map out a network of brain regions involved in the pathophysiology of depression and the neurobiological mechanisms of various treatments (128, 129); this work has helped postulate critical nodes within this network that might reasonably serve as targets for direct modulation. Such focal neuromodulation is now possible via noninvasive acute stimulation techniques [e.g., transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial DC stimulation (tDCS)] as well as methods that allow for chronic stimulation but require surgery [e.g., vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), direct cortical stimulation (DCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS)]. Two of these procedures (VNS and TMS) are currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of depression.

VNS.

VNS involves stimulating the vagus nerve via an electrode that is surgically attached to the nerve where it courses through the neck. A subcutaneously implanted pulse generator (IPG) controls stimulation and serves as the power supply for the system. Common treatment parameters include chronic but intermittent stimulation (e.g., 30 seconds on every 5 minutes). In 1997, VNS was approved by the FDA for the treatment of medication-resistant epilepsy. Observations of positive mood effects in some patients with epilepsy led to testing in medication-resistant depression. A double-blind, sham-controlled trial (on versus off stimulation) showed no statistically significant antidepressant effects for 10 weeks of active VNS, with a response of 15% for active VNS versus a 10% response rate with sham VNS (130). However, open-label data suggest increasing antidepressant efficacy over a year of stimulation [in combination with treatment-as-usual (TAU)] in patients in whom between two and six adequate treatments in the current episode have failed, with reported response rates of 27%–53% and remission rates of 16%–33% (131–133). Response and remission rates appear to either remain stable or may continue to increase with 2 years of stimulation (134, 135).

In a nonrandomized comparison with patients with TRD receiving only TAU, 1-year response rates were statistically significantly higher in the VNS + TAU group (27% versus 13%). In addition, VNS + TAU only showed a 23%–35% relapse rate over an additional year of stimulation (136) compared with a 62% relapse rate in the TAU-only group over an equivalent time period (137). However, a European study suggested that only 44% of patients receiving VNS sustain a response over an additional year of stimulation (133).

Risks of VNS surgery are minor, and adverse effects associated with acute and chronic stimulation include voice changes, coughing, and difficulty swallowing. In general, VNS appears to be cognitively safe, although stimulation intensity may be associated with some modest cognitive impairments (80, 138). The published data suggest that more than 80% of patients receiving VNS choose to continue stimulation even in the absence of an antidepressant response, suggesting that the treatment is generally well-tolerated.

TMS.

TMS uses an electromagnetic coil placed on the head to generate a depolarizing electrical current in the underlying cortex. Repetitive TMS (rTMS) delivers a train of stimuli at a set frequency, with “high-frequency” denoting ≥5 Hz stimulation and “low-frequency” denoting ≤1 Hz stimulation. A series of stimulation trains are given during each treatment session, and a typical treatment course involves daily sessions (each lasting about 1 hour) for 3–6 weeks. Patients are awake during treatment, and no anesthesia is required.

The types of rTMS most commonly studied for the treatment of depression include high-frequency rTMS (generally 5–20 Hz) applied to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and low-frequency rTMS (generally 1 Hz) applied to the right DLPFC. Safety and efficacy have been demonstrated for both approaches through a number of relatively small open-label and sham-controlled studies (139–144). Although effect sizes in favor of active rTMS have been moderately strong, absolute response rates have been relatively low (generally between 20% and 40% in sham-controlled studies).

Higher stimulation intensity and total number of pulses delivered (i.e., longer treatment sessions and more sessions over time) are associated with better antidepressant effects (145). High-frequency rTMS seems to be less effective in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients (67) and those with a longer versus shorter (<5 years) duration of the current episode (146). One study suggests lower efficacy in patients with late-life depression (147), although it is noted that this study probably did not use optimal treatment parameters, and the efficacy of rTMS may be lower if stimulation intensity is not adjusted upward to account for prefrontal cortical atrophy (148, 149), which was not done in this study of older patients.

Two multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled studies have helped clarify the safety and efficacy of rTMS as a monotherapy for medication-resistant depression. In an industry-sponsored study of medication-free patients who had not responded to at least one antidepressant medication, 4–6 weeks of high-frequency left DLPFC rTMS was associated with statistically significant antidepressant effects compared to sham rTMS, including higher response (24% versus 12%) and remission rates (14% versus 6%) after 6 weeks of treatment (150). However, a secondary analysis showed that the difference in antidepressant efficacy between active and sham rTMS was only statistically significant in those patients in whom no more than one medication (of adequate dose and duration) had failed in the current episode (151). A four-site National Institute of Mental Health-funded study using stimulation parameters and eligibility criteria similar to the industry-sponsored study also showed statistically significant antidepressant effects for active rTMS with remission rates similar to those in the industry study (152). These data also suggested that rTMS was more effective in patients with a lower degree of medication resistance. The long-term efficacy of rTMS is largely unknown, with studies suggesting relapse rates similar to those seen after ECT (153, 154). Repeated rTMS courses may be beneficial in helping to maintain benefit over time (155).

Although rTMS can result in seizures, this is highly unlikely when stimulation parameters are maintained within suggested safety guidelines (156). Common side effects of rTMS include pain at the site of stimulation and headaches, although most patients tolerate treatments very well (150, 152). There are no cognitive side effects associated with rTMS for depression (80). A potential disadvantage of rTMS as currently administered is the need for daily treatments over several weeks. However, in a recent open-label study testing accelerated rTMS (in which 15 treatment sessions were delivered over 2 days in an inpatient setting) (157), response and remission rates immediately after treatment were 43% and 29%, respectively, and were largely maintained over the next 6 weeks; side effects were similar to and no more severe than those seen with daily rTMS.

Magnetic seizure therapy.

More focal ECT administration is associated with fewer cognitive side effects but equivalent efficacy compared with less focal techniques (158, 159). Based on this finding, it was hypothesized that if seizures could be generated using very focal stimulation (i.e., with TMS), then efficacy approaching that of ECT could be achieved with an even better cognitive side effect profile. Similar to ECT, magnetic seizure therapy (MST) is performed under general anesthesia and involves the serial induction of seizures over several weeks. Preliminary data suggest that MST has antidepressant effects and may result in fewer cognitive side effects than ECT (160–162). Larger trials are currently underway.

tDCS.

tDCS is a noninvasive technique that modulates cortical excitatory tone (rather than causing neuronal depolarization) via a weak electrical current generated by two scalp electrodes. Five sessions of tDCS applied to the left DLPFC have shown mixed antidepressant efficacy in sham-controlled studies with one study finding a statistically significant antidepressant benefit (163) but another failing to replicate this (164). A third sham-controlled study using 10 sessions demonstrated antidepressant efficacy for active tDCS (165). In general, tDCS is very well-tolerated with no known cognitive side effects.

DCS.

Direct cortical stimulation involves electrical stimulation of the cortex via one or more electrodes surgically placed in either the epidural or subdural space. Similar to VNS, stimulation is driven by an IPG connected to the electrodes via subcutaneous wires. In a small pilot study of DCS of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices, three of five patients with TRD achieved remission after 7 months of chronic, intermittent stimulation (in these patients at least four adequate treatments had failed in the current episode) (166). DCS was very well tolerated, although one patient required explantation due to a scalp infection.

DBS.

DBS is achieved by placing a thin electrode through a burr hole in the skull into a specific brain region using imaging-guided stereotactic neurosurgical techniques. Electrodes can be placed in essentially any brain region and can be implanted unilaterally or bilaterally. Each electrode typically contains several distinct contacts that can be used to provide monopolar or bipolar stimulation. As with VNS and DCS, the electrodes are connected via subcutaneous wires to an IPG that controls stimulation.

DBS is an established treatment for patients with severe, treatment-resistant Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, and dystonia. DBS has largely replaced ablative surgery in these conditions because it can be adjusted to achieve maximal benefit with a minimum of side effects and can be turned off or completely removed in the case of severe, unwanted side effects. DBS of the anterior internal capsule [as a potential replacement for capsulotomy; this target is also referred to as the ventral capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS)] has shown potential safety and efficacy for patients with severe treatment-refractory OCD based on a multicenter open-label case series of 26 patients (167). This intervention is now FDA-approved via a Humanitarian Device Exemption. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus has also shown efficacy for OCD in a 6-month sham-controlled study (168).

Based on a converging neuroanatomical database suggesting a critical role for Brodmann area 25 in a neural network involved in depression and antidepressant response, Mayberg and colleagues (169, 170) demonstrated that open-label subcallosal cingulate DBS was associated with antidepressant effects in a cohort of 20 patients with severe TRD in whom at least four treatments had failed in the current episode. After 6 months of chronic stimulation, 60% of patients achieved response and 35% achieved remission; these effects were largely maintained over an additional 6 months with 72% of 6-month responders still meeting the response criteria at 12 months (and three additional patients achieving response by 12 months). Adverse events related to the procedure included skin infection (leading to explantation in two patients) and perioperative pain/headache related to surgery. There were no negative effects associated with acute or chronic DBS, and no negative cognitive effects (171).

In studies of VC/VS DBS for OCD, it was noted that many patients experienced significant improvement in comorbid depression (167), leading to testing of VC/VS DBS for TRD without comorbid OCD. After 6 months of chronic stimulation in 15 patients with TRD enrolled in a three-center open-label pilot study, 40% of patients achieved response and 27% achieved remission (172). At the last follow-up (an average of 24 ± 15 months after onset of stimulation, with a range of 6–51 months), there was a 53% response rate and a 33% remission rate. Adverse effects related to surgery and/or the device included perioperative pain and a DBS electrode break. Adverse effects of stimulation included hypomania, anxiety, perseverative speech, autonomic symptoms, and involuntary facial movements; these were mostly reversible with a stimulation parameter change. No cognitive side effects were described.

The most ventral aspect of the VC/VS DBS target includes the nucleus accumbens, a region implicated in reward processing. This region was targeted for DBS in a cohort of 10 patients with TRD in an open-label pilot study, with 50% of patients achieving an antidepressant response after 6 months of chronic stimulation (173). Case reports have described potential antidepressant efficacy of DBS of the inferior thalamic peduncle (which contains thalamocortical projection fibers) (174) and the habenula (which is involved in modulation of monoaminergic neurotransmission) (175).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

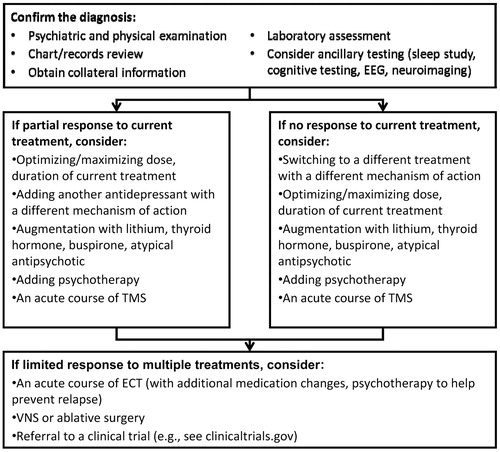

TRD is a prevalent and disabling condition with few evidence-based treatments available. Several medication augmentation or combination strategies currently exist, but the supporting database is limited and overall response and remission rates are relatively low in patients with TRD. Psychotherapy has shown significant potential as a treatment for depression and TRD but it is relatively understudied, and patient access can be limited. ECT is highly effective, even in TRD, for getting a patient out of a depressed episode, but relapse rates are high. A general algorithm for approaching the patient with TRD is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A Proposed General Algorithm for Approaching and Managing a Patient with TRD. EEG, Electroencephalography.

Advances in the management of TRD include the development of a number of novel pharmacological agents, many of which target systems outside the monoamines, as well as several focal neuromodulation techniques. Overall, there is optimism that these strategies will lead to antidepressant treatments to help achieve and sustain remission in a greater number of depressed patients. However, progress to date has been limited: despite encouraging preliminary results, none of the novel drugs are yet established for clinical use; the two FDA-approved brain stimulation therapies (VNS and TMS) are associated with relatively low response and remission rates, and neither has shown efficacy in those patients with the most extreme forms of treatment-resistant depression (i.e., more than six treatment failures in the current episode); and data on the remaining brain stimulation approaches are far too preliminary to draw meaningful conclusions regarding safety and efficacy. Still, the efforts of the past decade herald a new era of antidepressant treatment development, and it is highly likely that this work will eventually result in new and more powerful antidepressant therapies.

1 Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:617–627Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Miller IW, Keitner GI, Schatzberg AF, Klein DN, Thase ME, Rush AJ, Markowitz JC, Schlager DS, Kornstein SG, Davis SM, Harrison WM, Keller MB: The treatment of chronic depression, part 3: psychosocial functioning before and after treatment with sertraline or imipramine. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:608–619Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Crown WH, Finkelstein S, Berndt ER, Ling D, Poret AW, Rush AJ, Russell JM: The impact of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:963–971Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Nelsen MR, Dunner DL: Clinical and differential diagnostic aspects of treatment-resistant depression. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:43–50Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Papakostas GI, Petersen T, Pava J, Masson E, Worthington JJ 3rd, Alpert JE, Fava M, Nierenberg AA: Hopelessness and suicidal ideation in outpatients with treatment-resistant depression: prevalence and impact on treatment outcome. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003; 191:444–449Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Fawcett J, Harris SG: Suicide in treatment-refractory depression, in Treatment-Resistant Mood Disorders. New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp 479–488Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Everson SA, Roberts RE, Goldberg DE, Kaplan GA: Depressive symptoms and increased risk of stroke mortality over a 29-year period. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:1133–1138Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Honig A, Deeg DJ, Schoevers RA, van Eijk JT, van Tilburg W: Depression and cardiac mortality: results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:221–227Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Carney RM, Freedland KE: Treatment-resistant depression and mortality after acute coronary syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:410–417Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Murphy JM, Monson RR, Olivier DC, Sobol AM, Leighton AH: Affective disorders and mortality. A general population study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:473–480Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Thase M, Rush A: When at first you don't succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant non-responders. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(Suppl 13):23–29Google Scholar

12 Fava M: Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:649–659Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Fekadu A, Wooderson S, Donaldson C, Markopoulou K, Masterson B, Poon L, Cleare AJ: A multidimensional tool to quantify treatment resistance in depression: The Maudsley staging method. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:177–184Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Nierenberg AA, Amsterdam JD: Treatment-resistant depression: definition and treatment approaches. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(suppl):39–47; discussion 48–50Google Scholar

15 Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, Niederehe G, Thase ME, Lavori PW, Lebowitz BD, McGrath PJ, Rosenbaum JF, Sackeim HA, Kupfer DJ, Luther J, Fava M: Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1905–1917Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Berlim MT, Turecki G: What is the meaning of treatment resistant/refractory major depression (TRD)? A systematic review of current randomized trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 17:696–707Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Fekadu A, Wooderson SC, Markopoulo K, Donaldson C, Papadopoulos A, Cleare AJ: What happens to patients with treatment-resistant depression? A systematic review of medium to long term outcome studies. J Affect Disord 2009; 116:4–11Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Sackeim HA, Haskett RF, Mulsant BH, Thase ME, Mann JJ, Pettinati HM, Greenberg RM, Crowe RR, Cooper TB, Prudic J: Continuation pharmacotherapy in the prevention of relapse following electroconvulsive therapy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285:1299–1307Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Rasmussen KG, Mueller M, Rummans TA, Husain MM, Petrides G, Knapp RG, Fink M, Sampson SM, Bailine SH, Kellner CH: Is baseline medication resistance associated with potential for relapse after successful remission of a depressive episode with ECT? Data from the Consortium for Research on Electroconvulsive Therapy (CORE). J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:232–237Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Berlim MT, Fleck MP, Turecki G: Current trends in the assessment and somatic treatment of resistant/refractory major depression: an overview. Ann Med 2008; 40:149–159Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Keller M, Warshaw M, Clayton P, Goodwin F: Switching from ‘unipolar’ to bipolar II. An 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:114–123Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I, Bailer U, Bollen J, Demyttenaere K, Kasper S, Lecrubier Y, Montgomery S, Serretti A, Zohar J, Mendlewicz J, Group for the Study of Resistant Depression: Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a European multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:1062–1070Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS, National Comorbidity Survey Replication: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Bauer M, Forsthoff A, Baethge C, Adli M, Berghöfer A, Döpfmer S, Bschor T: Lithium augmentation therapy in refractory depression-update 2002. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 253:132–139Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, Quitkin FM, Wisniewski S, Lavori PW, Rosenbaum JF, Kupfer DJ: Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003; 26:457–494, xCrossref, Google Scholar

26 Chenu F, Bourin M: Potentiation of antidepressant-like activity with lithium: mechanism involved. Curr Drug Targets 2006; 7:159–163Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, McGrath PJ, Alpert JE, Warden D, Luther JF, Niederehe G, Lebowitz B, Shores-Wilson K, Rush AJ: A comparison of lithium and T3. Augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1519–1530; quiz 1665Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Aronson R, Offman HJ, Joffe RT, Naylor CD: Triiodothyronine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:842–848Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Altshuler LL, Bauer M, Frye MA, Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Szuba MP, Leight KL, Whybrow PC: Does thyroid supplementation accelerate tricyclic antidepressant response? A review and meta-analysis of the literature. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1617–1622Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Landén M, Björling G, Agren H, Fahlén T: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of buspirone in combination with an SSRI in patients with treatment-refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:664–668Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, Mehtonen OP, Muhonen TT, Naukkarinen HH: Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:448–452Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Bystritsky A, Ackerman DL, Rosen RM, Vapnik T, Gorbis E, Maidment KM, Saxena S: Augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder using adjunctive olanzapine: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:565–568Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Turner J, Mintz J, Saunders CS: Adjunctive risperidone in the treatment of chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:474–479Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Stein MB, Kline NA, Matloff JL: Adjunctive olanzapine for SSRI-resistant combat-related PTSD: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1777–1779Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Pollack MH, Simon NM, Zalta AK, Worthington JJ, Hoge EA, Mick E, Kinrys G, Oppenheimer J: Olanzapine augmentation of fluoxetine for refractory generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:211–215Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Brawman-Mintzer O, Knapp RG, Nietert PJ: Adjunctive risperidone in generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1321–1325Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Nelson JC, Papakostas GI: Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:980–991Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Mischoulon D, Nierenberg AA, Kizilbash L, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M: Strategies for managing depression refractory to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment: a survey of clinicians. Can J Psychiatry 2000; 45:476–481Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Fredman SJ, Fava M, Kienke AS, White CN, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF: Partial response, nonresponse, and relapse with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression: a survey of current “next-step” practices. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:403–408Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Zisook S, Rush AJ, Haight BR, Clines DC, Rockett CB: Use of bupropion in combination with serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:203–210Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Papakostas GI: Managing partial response or nonresponse: switching, augmentation, and combination strategies for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70(Suppl 6):16–25Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Carpenter LL, Yasmin S, Price LH: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antidepressant augmentation with mirtazapine. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:183–188Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Gillman PK: Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated. Br J Pharmacol 2007; 151:737–748Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Gómez Gómez JM, Teixidó Perramón C: Combined treatment with venlafaxine and tricyclic antidepressants in depressed patients who had partial response to clomipramine or imipramine: initial findings. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:285–289Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Amsterdam JD, García-España F, Rosenzweig M: Clomipramine augmentation in treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety 1997; 5:84–90Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Amsterdam JD, Quitkin FM: Lithium and tricyclic augmentation of fluoxetine treatment for resistant major depression: a double-blind, controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1372–1374Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Gloaguen V, Cottraux J, Cucherat M, Blackburn IM: A meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy in depressed patients. J Affect Disord 1998; 49:59–72Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Thase ME, Friedman ES, Biggs MM, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi MH, Luther JF, Fava M, Nierenberg AA, McGrath PJ, Warden D, Niederehe G, Hollon SD, Rush AJ: Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:739–752Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, Arnow B, Dunner DL, Gelenberg AJ, Markowitz JC, Nemeroff CB, Russell JM, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Zajecka J: A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1462–1470Crossref, Google Scholar

50 DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Young PR, Salomon RM, O'Reardon JP, Lovett ML, Gladis MM, Brown LL, Gallop R: Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:409–416Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Eisendrath SJ, Delucchi K, Bitner R, Fenimore P, Smit M, McLane M: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for treatment-resistant depression: a pilot study. Psychother Psychosom 2008; 77:319–320Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Fava GA, Savron G, Grandi S, Rafanelli C: Cognitive-behavioral management of drug-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:278–282, quiz 283–274Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Bressi C, Porcellana M, Marinaccio PM, Nocito EP, Magri L: Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy versus treatment as usual for depressive and anxiety disorders: a randomized clinical trial of efficacy. J Nerv Ment Dis 2010; 198:647–652Crossref, Google Scholar

54 de Maat S, Dekker J, Schoevers R, van Aalst G, Gijsbers-van Wijk C, Hendriksen M, Kool S, Peen J, Van R, de Jonghe F: Short psychodynamic supportive psychotherapy, antidepressants, and their combination in the treatment of major depression: a mega-analysis based on three randomized clinical trials. Depress Anxiety 2008; 25:565–574Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Driessen E, Cuijpers P, de Maat SC, Abbass AA, de Jonghe F, Dekker JJ: The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:25–36Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Salminen JK, Karlsson H, Hietala J, Kajander J, Aalto S, Markkula J, Rasi-Hakala H, Toikka T: Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and fluoxetine in major depressive disorder: a randomized comparative study. Psychother Psychosom 2008; 77:351–357Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, Andersson G: Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:1219–1229Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Amsterdam JD, Salomon RM, O'Reardon JP, Lovett ML, Young PR, Haman KL, Freeman BB, Gallop R: Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:417–422Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Conti S, Grandi S: Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1872–1876Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Bini L: Experimental researches on epileptic attacks induced by the electric current. Am J Psychiatry 1938; 94:172–174Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Fink M: Convulsive therapy: a review of the first 55 years. J Affect Disord 2001; 63:1–15Crossref, Google Scholar

62 The UK ECT Review Group: Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2003; 361:799–808Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Kellner CH, Knapp RG, Petrides G, Rummans TA, Husain MM, Rasmussen K, Mueller M, Bernstein HJ, O'Connor K, Smith G, Biggs M, Bailine SH, Malur C, Yim E, McClintock S, Sampson S, Fink M: Continuation electroconvulsive therapy vs pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention in major depression: a multisite study from the Consortium for Research in Electroconvulsive Therapy (CORE). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:1337–1344Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Sackeim HA, Dillingham EM, Prudic J, Cooper T, McCall WV, Rosenquist P, Isenberg K, Garcia K, Mulsant BH, Haskett RF: Effect of concomitant pharmacotherapy on electroconvulsive therapy outcomes: short-term efficacy and adverse effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:729–737Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, Malone KM, Pettinati HM, Stephens S, Greenberg R, Rifas SL, Sackeim HA: Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:985–992Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Kho KH, van Vreeswijk MF, Simpson S, Zwinderman AH: A meta-analysis of electroconvulsive therapy efficacy in depression. J ECT 2003; 19:139–147Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Grunhaus L, Dannon PN, Schreiber S, Dolberg OH, Amiaz R, Ziv R, Lefkifker E: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation is as effective as electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of nondelusional major depressive disorder: an open study. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:314–324Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Grunhaus L, Schreiber S, Dolberg OT, Polak D, Dannon PN: A randomized controlled comparison of electroconvulsive therapy and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in severe and resistant nonpsychotic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:324–331Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Lisanby SH, Maddox JH, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Sackeim HA: The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:581–590Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Fuller R, Keilp J, Lavori PW, Olfson M: The cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in community settings. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007; 32:244–254Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Kuhn R: The treatment of depressive states with G 22355 (imipramine hydrochloride). Am J Psychiatry 1958; 115:459–464Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Bailey SD, Bucci L, Gosline E, Kline NS, Park IH, Rochlin D, Saunders JC, Vaisberg M: Comparison of iproniazid with other amine oxidase inhibitors, including W-1544, JB-516, RO 4–1018, and RO 5–0700. Ann NY Acad Sci 1959; 80:652–668Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Kiloh LG, Child JP, Latner G: A controlled trial of iproniazid in the treatment of endogenous depression. J Ment Sci 1960; 106:1139–1144Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Jasper HH: A historical perspective. The rise and fall of prefrontal lobotomy. Adv Neurol 1995; 66:97–114Google Scholar

75 Hariz MI, Blomstedt P, Zrinzo L: Deep brain stimulation between 1947 and 1987: the untold story. Neurosurg Focus 2010; 29:E1Google Scholar

76 Sachdev P, Sachdev J: Sixty years of psychosurgery: its present status and its future. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1997; 31:457–464Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Marino Júnior R, Cosgrove GR: Neurosurgical treatment of neuropsychiatric illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997; 20:933–943Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Sachdev PS, Sachdev J: Long-term outcome of neurosurgery for the treatment of resistant depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:478–485Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Shields DC, Asaad W, Eskandar EN, Jain FA, Cosgrove GR, Flaherty AW, Cassem EH, Price BH, Rauch SL, Dougherty DD: Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64:449–454Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Moreines JL, McClintock SM, Holtzheimer PE: Neuropsychologic effects of neuromodulation techniques for treatment-resistant depression: a review. Brain Stimul (In press)Google Scholar

81 Clarke CE, Guttman M: Dopamine agonist monotherapy in Parkinson's disease. Lancet 2002; 360:1767–1769Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Zarate CA Jr, Payne JL, Singh J, Quiroz JA, Luckenbaugh DA, Denicoff KD, Charney DS, Manji HK: Pramipexole for bipolar II depression: a placebo-controlled proof of concept study. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56:54–60Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Goldberg JF, Burdick KE, Endick CJ: Preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole added to mood stabilizers for treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:564–566Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Lattanzi L, Dell'Osso L, Cassano P, Pini S, Rucci P, Houck PR, Gemignani A, Battistini G, Bassi A, Abelli M, Cassano GB: Pramipexole in treatment-resistant depression: a 16-week naturalistic study. Bipolar Disord 2002; 4:307–314Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Cassano P, Lattanzi L, Fava M, Navari S, Battistini G, Abelli M, Cassano GB: Ropinirole in treatment-resistant depression: a 16-week pilot study. Can J Psychiatry 2005; 50:357–360Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Cassano P, Lattanzi L, Soldani F, Navari S, Battistini G, Gemignani A, Cassano GB: Pramipexole in treatment-resistant depression: an extended follow-up. Depress Anxiety 2004; 20:131–138Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Arborelius L, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB: The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depression and anxiety disorders. J Endocrinol 1999; 160:1–12Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Gutman DA, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB: Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor and glucocorticoid receptor antagonists: new approaches to antidepressant treatment, in Current and Future Developments in Psychopharmacology. Edited by Benecke NI. Amsterdam, 2005, pp 133–158Google Scholar

89 Holsboer F: Corticotropin-releasing hormone modulators and depression. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2003; 4:46–50Google Scholar

90 Nemeroff CB: Recent advances in the neurobiology of depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 2002; 36(Suppl 2):6–23Google Scholar

91 Zobel AW, Nickel T, Künzel HE, Ackl N, Sonntag A, Ising M, Holsboer F: Effects of the high-affinity corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 antagonist R121919 in major depression: the first 20 patients treated. J Psychiatr Res 2000; 34:171–181Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Binneman B, Feltner D, Kolluri S, Shi Y, Qiu R, Stiger T: A 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial of CP-316,311 (a selective CRH1 antagonist) in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:617–620Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Zorrilla EP, Koob GF: Progress in corticotropin-releasing factor-1 antagonist development. Drug Discov Today 2010; 15:371–383Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI: Treatment of depression with antiglucocorticoid drugs. Psychosom Med 1999; 61:698–711Crossref, Google Scholar

95 Murphy BE, Filipini D, Ghadirian AM: Possible use of glucocorticoid receptor antagonists in the treatment of major depression: preliminary results using RU 486. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1993; 18:209–213Google Scholar

96 Belanoff JK, Flores BH, Kalezhan M, Sund B, Schatzberg AF: Rapid reversal of psychotic depression using mifepristone. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:516–521Crossref, Google Scholar

97 DeBattista C, Belanoff J, Glass S, Khan A, Horne RL, Blasey C, Carpenter LL, Alva G: Mifepristone versus placebo in the treatment of psychosis in patients with psychotic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 60:1343–1349Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Culman J, Unger T: Central tachykinins: mediators of defence reaction and stress reactions. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1995; 73:885–891Crossref, Google Scholar

99 Helke CJ, Krause JE, Mantyh PW, Couture R, Bannon MJ: Diversity in mammalian tachykinin peptidergic neurons: multiple peptides, receptors, and regulatory mechanisms. FASEB J 1990; 4:1606–1615Crossref, Google Scholar

100 Kramer MS, Cutler N, Feighner J, Shrivastava R, Carman J, Sramek JJ, Reines SA, Liu G, Snavely D, Wyatt-Knowles E, Hale JJ, Mills SG, MacCoss M, Swain CJ, Harrison T, Hill RG, Hefti F, Scolnick EM, Cascieri MA, Chicchi GG, Sadowski S, Williams AR, Hewson L, Smith D, Carlson EJ, Hargreaves RJ, Rupniak NM: Distinct mechanism for antidepressant activity by blockade of central substance P receptors. Science 1998; 281:1640–1645Crossref, Google Scholar

101 Culman J, Klee S, Ohlendorf C, Unger T: Effect of tachykinin receptor inhibition in the brain on cardiovascular and behavioral responses to stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 280:238–246Google Scholar

102 Geracioti TD Jr, Carpenter LL, Owens MJ, Baker DG, Ekhator NN, Horn PS, Strawn JR, Sanacora G, Kinkead B, Price LH, Nemeroff CB: Elevated cerebrospinal fluid substance p concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:637–643Crossref, Google Scholar

103 Bondy B, Baghai TC, Minov C, Schüle C, Schwarz MJ, Zwanzger P, Rupprecht R, Möller HJ: Substance P serum levels are increased in major depression: preliminary results. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:538–542Crossref, Google Scholar

104 Keller M, Montgomery S, Ball W, Morrison M, Snavely D, Liu G, Hargreaves R, Hietala J, Lines C, Beebe K, Reines S: Lack of efficacy of the substance p (neurokinin1 receptor) antagonist aprepitant in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:216–223Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Kramer MS, Winokur A, Kelsey J, Preskorn SH, Rothschild AJ, Snavely D, Ghosh K, Ball WA, Reines SA, Munjack D, Apter JT, Cunningham L, Kling M, Bari M, Getson A, Lee Y: Demonstration of the efficacy and safety of a novel substance P (NK1) receptor antagonist in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29:385–392Crossref, Google Scholar

106 Herpfer I, Lieb K: Substance P receptor antagonists in psychiatry: rationale for development and therapeutic potential. CNS Drugs 2005; 19:275–293Crossref, Google Scholar

107 Paul IA, Skolnick P: Glutamate and depression: clinical and preclinical studies. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003; 1003:250–272Crossref, Google Scholar

108 Zarate CA Jr, Du J, Quiroz J, Gray NA, Denicoff KD, Singh J, Charney DS, Manji HK: Regulation of cellular plasticity cascades in the pathophysiology and treatment of mood disorders: role of the glutamatergic system. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003; 1003:273–291Crossref, Google Scholar

109 McEwen BS, Seeman T: Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress. Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci 1999; 896:30–47Crossref, Google Scholar

110 Sapolsky RM: The possibility of neurotoxicity in the hippocampus in major depression: a primer on neuron death. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:755–765Crossref, Google Scholar

111 Rogóz Z, Skuza G, Maj J, Danysz W: Synergistic effect of uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists and antidepressant drugs in the forced swimming test in rats. Neuropharmacology 2002; 42:1024–1030Crossref, Google Scholar

112 Rogóz Z, Skuza G, Kuśmider M, Wójcikowski J, Kot M, Daniel WA: Synergistic effect of imipramine and amantadine in the forced swimming test in rats. Behavioral and pharmacokinetic studies. Pol J Pharmacol 2004; 56:179–185Google Scholar

113 Stryjer R, Strous RD, Shaked G, Bar F, Feldman B, Kotler M, Polak L, Rosenzcwaig S, Weizman A: Amantadine as augmentation therapy in the management of treatment-resistant depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2003; 18:93–96Crossref, Google Scholar

114 Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK: A randomized trial of an N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:856–864Crossref, Google Scholar

115 Diazgranados N, Ibrahim L, Brutsche NE, Newberg A, Kronstein P, Khalife S, Kammerer WA, Quezado Z, Luckenbaugh DA, Salvadore G, Machado-Vieira R, Manji HK, Zarate CA Jr: A randomized add-on trial of an N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67:793–802Crossref, Google Scholar

116 aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW, Perez AM, Reich DL, Charney DS, Mathew SJ: Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67:139–145Crossref, Google Scholar

117 Phelps LE, Brutsche N, Moral JR, Luckenbaugh DA, Manji HK, Zarate CA Jr: Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65:181–184Crossref, Google Scholar

118 Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Quiroz JA, De Jesus G, Denicoff KK, Luckenbaugh DA, Manji HK, Charney DS: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:153–155Crossref, Google Scholar

119 Muhonen LH, Lönnqvist J, Juva K, Alho H: Double-blind, randomized comparison of memantine and escitalopram for the treatment of major depressive disorder comorbid with alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:392–399Crossref, Google Scholar

120 Sanacora G, Kendell SF, Levin Y, Simen AA, Fenton LR, Coric V, Krystal JH: Preliminary evidence of riluzole efficacy in antidepressant-treated patients with residual depressive symptoms. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61:822–825Crossref, Google Scholar

121 Zarate CA Jr, Payne JL, Quiroz J, Sporn J, Denicoff KK, Luckenbaugh D, Charney DS, Manji HK: An open-label trial of riluzole in patients with treatment-resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:171–174Crossref, Google Scholar

122 Zarate CA Jr, Quiroz JA, Singh JB, Denicoff KD, De Jesus G, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK: An open-label trial of the glutamate-modulating agent riluzole in combination with lithium for the treatment of bipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:430–432Crossref, Google Scholar

123 Mathew SJ, Murrough JW, aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Reich DL, Charney DS: Riluzole for relapse prevention following intravenous ketamine in treatment-resistant depression: a pilot randomized, placebo-controlled continuation trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010; 13:71–82Crossref, Google Scholar

124 Furey ML, Drevets WC: Antidepressant efficacy of the antimuscarinic drug scopolamine: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:1121–1129Crossref, Google Scholar

125 Drevets WC, Furey ML: Replication of scopolamine's antidepressant efficacy in major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67:432–438Crossref, Google Scholar

126 Papakostas GI: Evidence for S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM-e) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70(Suppl 5):18–22Crossref, Google Scholar

127 Papakostas GI, Mischoulon D, Shyu I, Alpert JE, Fava M: S-Adenosyl methionine (SAMe) augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167:942–948Crossref, Google Scholar

128 Mayberg HS: Targeted electrode-based modulation of neural circuits for depression. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:717–725Crossref, Google Scholar

129 Price JL, Drevets WC: Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35:192–216Crossref, Google Scholar

130 Rush AJ, Marangell LB, Sackeim HA, George MS, Brannan SK, Davis SM, Howland R, Kling MA, Rittberg BR, Burke WJ, Rapaport MH, Zajecka J, Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Ginsberg D, Cooke RG: Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, controlled acute phase trial. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:347–354Crossref, Google Scholar

131 Sackeim HA, Rush AJ, George MS, Marangell LB, Husain MM, Nahas Z, Johnson CR, Seidman S, Giller C, Haines S, Simpson RK Jr, Goodman RR: Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, side effects, and predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001; 25:713–728Crossref, Google Scholar

132 Marangell LB, Rush AJ, George MS, Sackeim HA, Johnson CR, Husain MM, Nahas Z, Lisanby SH: Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for major depressive episodes: one year outcomes. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:280–287Crossref, Google Scholar

133 Schlaepfer TE, Frick C, Zobel A, Maier W, Heuser I, Bajbouj M, O'Keane V, Corcoran C, Adolfsson R, Trimble M, Rau H, Hoff HJ, Padberg F, Müller-Siecheneder F, Audenaert K, Van den Abbeele D, Matthews K, Christmas D, Stanga Z, Hasdemir M: Vagus nerve stimulation for depression: efficacy and safety in a European study. Psychol Med 2008; 38:651–661Crossref, Google Scholar

134 Nahas Z, Marangell LB, Husain MM, Rush AJ, Sackeim HA, Lisanby SH, Martinez JM, George MS: Two-year outcome of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment of major depressive episodes. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1097–1104Crossref, Google Scholar

135 Bajbouj M, Merkl A, Schlaepfer TE, Frick C, Zobel A, Maier W, O'Keane V, Corcoran C, Adolfsson R, Trimble M, Rau H, Hoff HJ, Padberg F, Müller-Siecheneder F, Audenaert K, van den Abbeele D, Matthews K, Christmas D, Eljamel S, Heuser I: Two-year outcome of vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2010; 30:273–281Crossref, Google Scholar

136 Sackeim HA, Brannan SK, Rush AJ, George MS, Marangell LB, Allen J: Durability of antidepressant response to vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 10:817–826Crossref, Google Scholar

137 Dunner DL, Rush AJ, Russell JM, Burke M, Woodard S, Wingard P, Allen J: Prospective, long-term, multicenter study of the naturalistic outcomes of patients with treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:688–695Crossref, Google Scholar

138 Helmstaedter C, Hoppe C, Elger CE: Memory alterations during acute high-intensity vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsy Res 2001; 47:37–42Crossref, Google Scholar

139 Holtzheimer PE 3rd, Russo J, Avery DH: A meta-analysis of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 2001; 35:149–169Google Scholar

140 Burt T, Lisanby SH, Sackeim HA: Neuropsychiatric applications of transcranial magnetic stimulation: a meta analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2002; 5:73–103Crossref, Google Scholar

141 Kozel FA, George MS: Meta-analysis of left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to treat depression. J Psychiatr Pract 2002; 8:270–275Crossref, Google Scholar

142 Martin JL, Barbanoj MJ, Schlaepfer TE, Thompson E, Pérez V, Kulisevsky J: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of depression. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182:480–491Crossref, Google Scholar

143 Schutter DJ: Quantitative review of the efficacy of slow-frequency magnetic brain stimulation in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med 2010; 40:1789–1795Crossref, Google Scholar

144 Fitzgerald PB, Brown TL, Marston NA, Daskalakis ZJ, De Castella A, Kulkarni J: Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:1002–1008Google Scholar

145 Gershon AA, Dannon PN, Grunhaus L: Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:835–845Crossref, Google Scholar

146 Holtzheimer PE 3rd, Russo J, Claypoole KH, Roy-Byrne P, Avery DH: Shorter duration of depressive episode may predict response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Depress Anxiety 2004; 19:24–30Crossref, Google Scholar

147 Manes F, Jorge R, Morcuende M, Yamada T, Paradiso S, Robinson RG: A controlled study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment of depression in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr 2001; 13:225–231Crossref, Google Scholar

148 Nahas Z, Teneback CC, Kozel A, Speer AM, DeBrux C, Molloy M, Stallings L, Spicer KM, Arana G, Bohning DE, Risch SC, George MS: Brain effects of TMS delivered over prefrontal cortex in depressed adults: role of stimulation frequency and coil-cortex distance. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:459–470Crossref, Google Scholar

149 Kozel FA, Nahas Z, deBrux C, Molloy M, Lorberbaum JP, Bohning D, Risch SC, George MS: How coil-cortex distance relates to age, motor threshold, and antidepressant response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 12:376–384Crossref, Google Scholar

150 O'Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, Sampson S, Isenberg KE, Nahas Z, McDonald WM, Avery D, Fitzgerald PB, Loo C, Demitrack MA, George MS, Sackeim HA: Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:1208–1216Crossref, Google Scholar

151 Lisanby SH, Husain MM, Rosenquist PB, Maixner D, Gutierrez R, Krystal A, Gilmer W, Marangell LB, Aaronson S, Daskalakis ZJ, Canterbury R, Richelson E, Sackeim HA, George MS: Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: clinical predictors of outcome in a multisite, randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009; 34:522–534Crossref, Google Scholar

152 George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, McDonald WM, Durkalski V, Pavlicova M, Anderson B, Nahas Z, Bulow P, Zarkowski P, Holtzheimer PE 3rd, Schwartz T, Sackeim HA: Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: a sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67:507–516Crossref, Google Scholar

153 Avery DH, Holtzheimer PE 3rd, Fawaz W, Russo J, Neumaier J, Dunner DL, Haynor DR, Claypoole KH, Wajdik C, Roy-Byrne P: A controlled study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in medication-resistant major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:187–194Crossref, Google Scholar

154 Dannon PN, Dolberg OT, Schreiber S, Grunhaus L: Three and six-month outcome following courses of either ECT or rTMS in a population of severely depressed individuals—preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:687–690Crossref, Google Scholar

155 Demirtas-Tatlidede A, Mechanic-Hamilton D, Press DZ, Pearlman C, Stern WM, Thall M, Pascual-Leone A: An open-label, prospective study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the long-term treatment of refractory depression: reproducibility and duration of the antidepressant effect in medication-free patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:930–934Crossref, Google Scholar

156 Wassermann EM: Risk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: report and suggested guidelines from the International Workshop on the Safety of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, June 5–7, 1996. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998; 108:1–16Crossref, Google Scholar

157 Holtzheimer PE 3rd, McDonald WM, Mufti M, Kelley ME, Quinn S, Corso G, Epstein CM: Accelerated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety 2010; 27:960–963Crossref, Google Scholar

158 Lisanby SH: Electroconvulsive therapy for depression. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1939–1945Crossref, Google Scholar

159 Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Nobler MS, Fitzsimons L, Lisanby SH, Payne N, Berman RM, Brakemeier EL, Perera T, Devanand DP: Effects of pulse width and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. Brain Stimul 2008; 1:71–83Crossref, Google Scholar

160 Lisanby SH, Luber B, Schlaepfer TE, Sackeim HA: Safety and feasibility of magnetic seizure therapy (MST) in major depression: randomized within-subject comparison with electroconvulsive therapy. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:1852–1865Crossref, Google Scholar

161 Kosel M, Frick C, Lisanby SH, Fisch HU, Schlaepfer TE: Magnetic seizure therapy improves mood in refractory major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:2045–2048Crossref, Google Scholar

162 White PF, Amos Q, Zhang Y, Stool L, Husain MM, Thornton L, Downing M, McClintock S, and Lisanby SH: Anesthetic considerations for magnetic seizure therapy: a novel therapy for severe depression. Anesth Analg 2006; 103:76–80, table of contentsCrossref, Google Scholar

163 Fregni F, Boggio PS, Nitsche MA, Marcolin MA, Rigonatti SP, Pascual-Leone A: Treatment of major depression with transcranial direct current stimulation. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8:203–204Crossref, Google Scholar

164 Loo CK, Sachdev P, Martin D, Pigot M, Alonzo A, Malhi GS, Lagopoulos J, Mitchell P: A double-blind, sham-controlled trial of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010; 13:61–69Crossref, Google Scholar

165 Boggio PS, Rigonatti SP, Ribeiro RB, Myczkowski ML, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial on the efficacy of cortical direct current stimulation for the treatment of major depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008; 11:249–254Crossref, Google Scholar

166 Nahas Z, Anderson BS, Borckardt J, Arana AB, George MS, Reeves ST, Takacs I: Bilateral epidural prefrontal cortical stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67:101–109Crossref, Google Scholar

167 Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DA Jr, Rezai AR, Friehs GM, Okun MS, Shapira NA, Foote KD, Cosyns PR, Kubu CS, Malloy PF, Salloway SP, Giftakis JE, Rise MT, Machado AG, Baker KB, Stypulkowski PH, Goodman WK, Rasmussen SA, Nuttin BJ: Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Mol Psychiatry 2010; 15:64–79Crossref, Google Scholar

168 Mallet L, Polosan M, Jaafari N, Baup N, Welter ML, Fontaine D, du Montcel ST, Yelnik J, Chéreau I, Arbus C, Raoul S, Aouizerate B, Damier P, Chabardès S, Czernecki V, Ardouin C, Krebs MO, Bardinet E, Chaynes P, Burbaud P, Cornu P, Derost P, Bougerol T, Bataille B, Mattei V, Dormont D, Devaux B, Vérin M, Houeto JL, Pollak P, Benabid AL, Agid Y, Krack P, Millet B, Pelissolo A, STOC Study Group: Subthalamic nucleus stimulation in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2121–2134Crossref, Google Scholar

169 Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, Schwalb JM, Kennedy SH: Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 2005; 45:651–660Crossref, Google Scholar

170 Lozano AM, Mayberg HS, Giacobbe P, Hamani C, Craddock RC, Kennedy SH: Subcallosal cingulate gyrus deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64:461–467Crossref, Google Scholar

171 McNeely HE, Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Kennedy SH: Neuropsychological impact of Cg25 deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: preliminary results over 12 months. J Nerv Ment Dis 2008; 196:405–410Crossref, Google Scholar

172 Malone DA Jr, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Friehs GM, Eskandar EN, Rauch SL, Rasmussen SA, Machado AG, Kubu CS, Tyrka AR, Price LH, Stypulkowski PH, Giftakis JE, Rise MT, Malloy PF, Salloway SP, Greenberg BD: Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65:267–275Crossref, Google Scholar

173 Bewernick BH, Hurlemann R, Matusch A, Kayser S, Grubert C, Hadrysiewicz B, Axmacher N, Lemke M, Cooper-Mahkorn D, Cohen MX, Brockmann H, Lenartz D, Sturm V, Schlaepfer TE: Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases ratings of depression and anxiety in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67:110–116Crossref, Google Scholar

174 Jimenez F, Velasco F, Salin-Pascual R, Hernandez JA, Velasco M, Criales JL and Nicolini H: A patient with a resistant major depression disorder treated with deep brain stimulation in the inferior thalamic peduncle. Neurosurgery 2005; 57:585–593Crossref, Google Scholar

175 Sartorius A, Kiening KL, Kirsch P, von Gall CC, Haberkorn U, Unterberg AW, Henn FA and Meyer-Lindenberg A: Remission of major depression under deep brain stimulation of the lateral habenula in a therapy-refractory patient. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67:e9–e11Crossref, Google Scholar