Depression and Coronary Heart Disease: Recommendations for Screening, Referral, and Treatment

Abstract

Depression is commonly present in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and is independently associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Screening tests for depressive symptoms should be applied to identify patients who may require further assessment and treatment. This multispecialty consensus document reviews the evidence linking depression with CHD and provides recommendations for healthcare providers for the assessment, referral, and treatment of depression.

(Reprinted with permission from Circulation 2008; 118:1768–1775. © 2008 American Heart Association Inc.)

Over the past 40 years, more than 60 prospective studies have examined the link between established indices of depression and prognosis in individuals with known coronary heart disease (CHD) (1). Since the first major review articles were published in the late 1990s (2–5), there have been more than 100 additional narrative reviews of this literature, as well as numerous meta-analyses examining the role of depression on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (6–11). Despite differences in samples, duration of follow-up, and assessment of depression and depressive symptoms, these studies have demonstrated relatively consistent results.

Depression is ≈3 times more common in patients after an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) than in the general community (12). Assessments conducted in the hospital indicate that 15% to 20% of patients with myocardial infarction (MI) meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (13) criteria for major depression (duration since admission, no assessment of functional impairment), and an even greater proportion show an elevated level of depressive symptoms (14–16). Prevalence rates of depression have been shown to be higher among women in the general population (17) and among cardiac patients (18), with recent evidence suggesting that young women may be at particularly high risk for depression after AMI (19). Prevalence estimates in patients hospitalized for unstable angina, angioplasty, bypass surgery, and valve surgery are similar to those in patients with AMI, with slightly higher levels reported in patients with congestive heart failure (1–9). Less is known about the prevalence of depression in outpatient samples; however, available studies suggest that both major depression and elevated depressive symptoms are also considerably higher among people with CHD living in the community as compared with individuals without CHD (9–12). A recent study based on National Health Interview Survey data of 30,801 adults found the 12-month prevalence of major depression to be 9.3% in individuals with cardiac disease as compared with 4.8% in those with no comorbid medical illness (20). Depression prevalence ranged from 7.9% to 17% in those with other chronic medical conditions. The study found that the coexistence of major depression with chronic conditions is associated with more ambulatory care visits, emergency department visits, days spent in bed because of illness, and functional disability.

Major depression and elevated depressive symptoms are associated with worse prognosis in patients with CHD (10, 21–25). In fact, most studies that have examined the relationship between increasing depression severity and cardiac events have shown a dose-response relationship, with more severe depression associated with earlier and more severe cardiac events (10, 22). Not all individual studies have shown a significant link between depression and prognosis after statistical adjustment for measures of cardiac disease severity. Although some argue that this association is entirely explained by cardiac disease severity, most studies show robust links that remain statistically significant after adjustment for other potential confounders (8, 15, 22, 26–28). Methodological differences, including sample sizes, sample characteristics, selection of covariates, definition of outcomes, and length of follow-up, may account for the variations across studies (1, 6–8, 29, 30). There is general consensus that depression remains associated with at least a doubling in risk of cardiac events over 1 to 2 years after an MI (1, 6, 7, 9, 21).

Both biological and behavioral mechanisms have been proposed to explain the link between depression and CHD. In comparison with nondepressed individuals, depressed patients with CHD frequently have higher levels of biomarkers found to predict cardiac events or promote atherosclerosis. Although not always consistent, several studies in depressed patients with coronary artery disease have reported reduced heart rate variability (suggesting increased sympathetic activity and/or reduced vagal activity) (31), evidence of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction (32), increased plasma platelet factor 4 and β-thromboglobulin (suggesting enhanced platelet activation) (33, 34), impaired vascular function (35), and increased C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and fibrinogen levels (suggesting increased innate inflammatory response) (36, 37). Depression can be highly correlated with other mental disorders (eg, anxiety disorders) that have also been associated with adverse cardiac outcomes (38, 39). Certain behaviors and social characteristics in depressed patients may also contribute to the development and progression of coronary disease. These include diet, exercise, medication adherence, and tobacco use, as well as social isolation and chronic life stress (21, 40–44). Although the specific behavioral and biological processes remain unclear, the alteration of these processes is associated with depressive symptoms, consistently in a direction that increases cardiovascular risk.

Beyond what many believe to be its pathophysiological effect on the heart, depression is associated with decreased adherence to medications (21, 40, 45, 46) and triple the risk of noncompliance with medical treatment regimens (47). Depression reduces the chances of successful modifications of other cardiac risk factors (48) and participation in cardiac rehabilitation (49, 50) and is associated with higher healthcare utilization and costs (9, 51, 52) and, not surprisingly, greatly reduced quality of life (24, 53, 54). Thus whether depression affects cardiac outcomes directly or indirectly, the need to screen and treat-depression is imperative (55).

ASSESSMENT OF DEPRESSION AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS

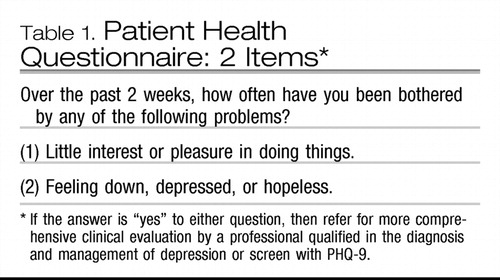

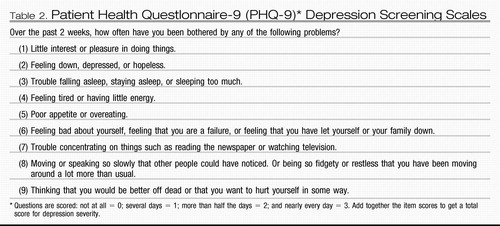

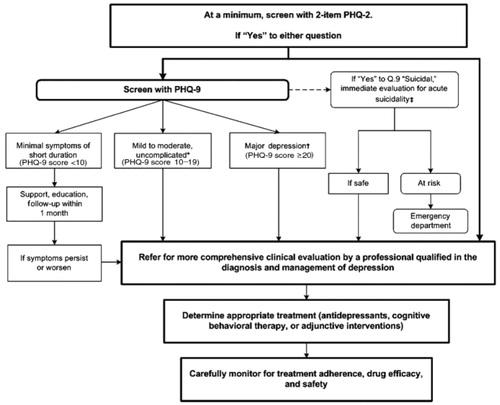

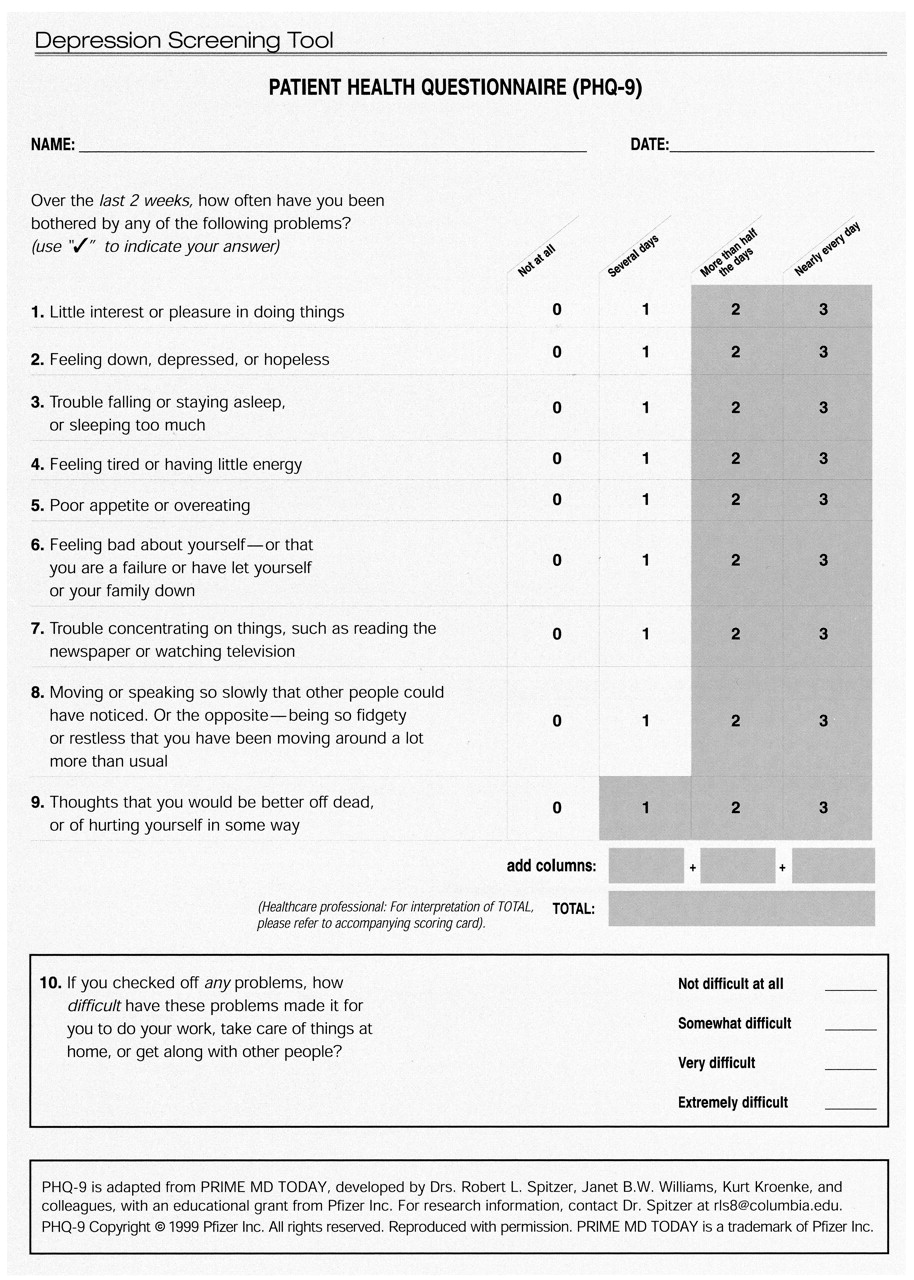

At a minimum, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) (56) provides 2 questions that are recommended for identifying currently depressed patients (Table 1). If the answer is “yes” to either or both questions, it is recommended that all 9 PHQ items (PHQ-9; Table 2) be asked (57). The PHQ-9 is a brief depression screening instrument (Appendix) (66). Most patients are able to complete it without assistance in 5 minutes or less. It yields both a provisional depression diagnosis and a severity score that can be used for treatment selection and monitoring. The PHQ-9 has been shown to have reasonable sensitivity and specificity for patients with CHD (58–60). For patients with mild symptoms, follow-up during a subsequent visit is advised. In patients with high depression scores, a physician or nurse should review the answers with the patient. Other assessment tools and their use for research purposes have been discussed elsewhere (61). Any of these tools can provide a useful initial assessment, but it must be recognized that depressive symptoms may present within the context of a complex medical condition. This current science advisory builds on the approach developed by the MacArthur Initiative on Depression and Primary Care (62–64), which provides empirically supported tools and procedures for the recognition and treatment of depression in primary care settings for depression screening and care guidelines for cardiologists (65–66). However, patients with screening scores that indicate a high probability of depression (PHQ-9 score of 10 or higher) should be referred for a more comprehensive clinical evaluation by a professional qualified to evaluate and determine a suitable individualized treatment plan (Figure). Patients who meet the threshold for a more comprehensive clinical evaluation should be evaluated for the presence of other mental disorders (eg, anxiety) that have also been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes in cardiac patients (38–39).

|

Table 1. Patient Health Questionnaire: 2 Items*

|

Table 2. Patient Health Questlonnaire-9 (PHQ-9)* Depression Screening Scales

*Meets diagnostic criteria for major depression, has a PHQ-9 score of 10–19, has had no more than 1 or 2 prior episodes of depression, and screens negative for bipolar disorder, suicidality, significant substance abuse, or other major psychiatric problems. †Meets the diagnostic criteria for major depression and 1) has a PHQ-9 score ≥20; or 2) has had 3 or more prior depressive episodes; or 3) screens positive for bipolar disorder, suicidality, significant substance abuse, or other major psychiatric problem. ‡If “Yes” to Q.9 “suicidal,” immediately evaluate for acute suicidality. If safe, refer for more comprehensive clinical evaluation; if at risk for suicide, escort the patient to the emergency department.

Cardiologists should take depression into account in the management of CHD, regardless of whether they treat the depression or refer the patient to a healthcare provider who is qualified in the assessment and treatment of depression, which often may be the patient's primary care provider (65). Current evidence indicates that only approximately half of cardiovascular physicians report that they treat depression in their patients, and not all patients who are recognized as depressed are teated (67). Some physicians are reluctant to treat depression in patients with CHD because they believe that depression after an acute cardiac event is a “normal” reaction to a stressful life event that will remit when the acute event stabilizes and the individual resumes customary activities. However, in many cases, depression may occur before and continue after an acute cardiac event (68). Although there is currently no direct evidence that screening for depression leads to improved outcomes in cardiovascular populations, depression has been linked with increased morbidity and mortality, poorer risk-factor modification, lower rates of cardiac rehabilitation, and reduced quality of life. Therefore, it is important to assess depression in cardiac patients with the goal of targeting those most in need of treatment and support services.

DEPRESSION TREATMENT

Treatment options include antidepressant drugs, cognitive behavioral therapy, and physical activity such as aerobic exercise and cardiac rehabilitation.

Antidepressant drugs

Although antidepressant use has been associated with both increased and decreased cardiac risk in some epidemiological studies (69), randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that 2 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants, sertraline and citalopram, are safe for patients with CHD and effective for moderate, severe, or recurrent depression (70, 71). Nonrandomizcd, post hoc analysis of the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) study revealed that patients treated with an SSRI, whether assigned to receive cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care, had a 42% reduction in death or recurrent MI as compared with the depressed patients not receiving an antidepressant (72). Given that SSRI treatment soon after AMI appears safe, is relatively inexpensive, and may be effective for post-AMI depression, it seems appropriate to screen and treat depression. Not only does treatment improve mood and quality of life, but studies have shown that depression interferes with compliance, and treatment of depressive symptoms may improve medication adherence in patients after AMI (73).

Sertraline and citalopram are the first-line antidepressant drugs for patients with CHD. Patients with recurrent depression who previously tolerated and responded well to another antidepressant may resume taking that agent instead, unless it is now contraindicated. For example, tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are contraindicated for many patients with heart disease because of their cardiotoxic side effects (74). If pharmacological treatment is initiated, patients should be observed closely for the first 2 months and regularly thereafter to monitor suicidal risk, ensure medication compliance, and detect and manage adverse effects. Approximately 15% to 25% of patients stop their antidepressants during the first 6 months of treatment because of adverse effects or lack of efficacy (14–75). Therefore, potential drug interactions or adverse effects should be closely monitored.

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Cognitive behavioral therapy can benefit depression in cardiac patients (76). It may be an alternative for cardiac patients who cannot tolerate antidepressants or who may prefer a nonpharmacological or counseling approach to treatment. Also, many patients with moderate to severe depression may respond better to the combination of an antidepressant and psychotherapy than to either treatment alone. Referral to a qualified psychotherapist is necessary. In ENRICHD, a randomized controlled trial, at least 12 to 16 sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy over 12 weeks were advocated to achieve remission of moderate to severe depression (77, 78). In clinical practice, the duration and frequency can be customized by the treating therapist to meet the individual needs of the patient; some patients may prefer and do well with a less intensive regimen.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY/EXERCISE

Aerobic exercise (79) and cardiac rehabilitation 80) can reduce depressive symptoms in addition to improving cardiovascular fitness. Although depression may be a barrier to participation in cardiac rehabilitation and exercise programs, cardiologists can help depressed patients overcome this barrier by providing encouragement and follow-up contacts. They should also enlist the help of spouses, partners, or family to improve adherence. The prescription of exercise would need to be individually assessed based on cardiac status and exercise capacity of the individual (81).

The depression guidelines for the primary care population have documented that treatment with appropriate pharmacological agents versus behavioral interventions are similarly effective; the combination of both has the benefit of lower relapse rates (63, 64). There is no evidence that treatments for depression are differentially effective in cardiac versus other patients. There is as yet no direct evidence showing that treatment of depression improves cardiac outcomes; patients may remain at increased risk for major cardiac events and mortality even when treated for depression (72). Evidence suggests that depressed patients who are not responsive to treatment for depression may be at greater risk for adverse cardiac events (82). Aggressive cardiologic care may help mitigate this increased risk. Depressed patients may also require additional clinical management to ensure compliance with cardiac treatment regimens and to promote lifestyle behavior change.

SUMMARY

In summary, the high prevalence of depression in patients with CHD supports a strategy of increased awareness and screening for depression in patients with CHD. Specifically, we recommend the following:

| •. | Routine screening for depression in patients with CHD in various settings, including the hospital, physician's office, clinic, and cardiac rehabilitation center. The opportunity to screen for and treat depression in cardiac patients should not be missed, as effective depression treatment may improve health outcomes. | ||||

| •. | Patients with positive screening results should be evaluated by a professional qualified in the diagnosis and management of depression. | ||||

| •. | Patients with cardiac disease who are under treatment for depression should be carefully monitored for adherence to their medical care, drug efficacy, and safety with respect to their cardiovascular as well as mental health. Monitoring mental health may include, but is not limited to, the assessment of patients receiving antidepressants for possible worsening of depression or suicidality, especially during initial treatment when doses may be adjusted, changed, or discontinued. Monitoring cardiovascular health may include, but is not limited to, more frequent office visits, ECGs, or assessment of blood levels of medications on the basis of the individual needs and circumstances of the patient. | ||||

| •. | Coordination of care between healthcare providers is essential in patients with combined medical and mental health diagnoses. | ||||

For Writing Group Disclosures refer to original article.

1 Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F. Recent evidence linking coronary heart disease and depression. Can J Psychiatry. 2006; 51: 730– 737.Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Glassman AH, Shapiro PA. Depression and the course of coronary artery disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1998; 155: 4– 11.Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch Gen Psychienry. 1998; 55: 580– 592.Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology: psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 1999; 318: 1460– 1467.Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Rozanski A. Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999; 99: 2192– 2217.Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Barth J. Schumacher M. Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patienls with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66: 802– 813.Crossref, Google Scholar

7 van Melle JP, de Jonge P, Spijkerman TA, Tijssen JG, Ormel J, van Veldhuisen DJ, van den Brink RH, van den Berg MP. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66: 814– 822.Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H. Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146 558 participants in 54 observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27: 2763– 2774.Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48: 1527– 1537.Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Rugulies R. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 23: 51– 61.Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Wulsin LR, Singal BM. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65: 201– 210.Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Thombs BD, Bass EB, Ford DE, Stewart KJ, Tsilidis KK, Patel U, Fauerbach JA, Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC. Prevalence of depression in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006; 21: 30– 38.Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.Google Scholar

14 Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N. Depression in patients with cardiac disease: a practical review. J Psychosom Res. 2000; 48: 379– 391.Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Carney RM. Freedland KE. Depression, mortality, and medical morbidity in patients with coronary heart disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2003; 54: 241– 247.Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC, Patel UV, Thombs BD, Ford DE, Fauerbach JA, McCann UD, Stewart KJ, Tsilidis KK, Patel AL, Feuerstein CJ, Bass EB. Post-myocardial infarction depression. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2005; l– 8.Google Scholar

17 Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003; 74: 5– 13.Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Pilote L, Dasgupta K, Guru V, Humphries KH, McGrath J, Norris C, Rabi D, Tremblay J, Alamian A, Barnett T, Cox J, Ghali WA, Grace S, Hamet P, Ho T, Kirkland S, Lambert M, Libersan D, O'Loughlin J, Paradis G, Petrovich M, Tagalakis V. A comprehensive view of sex-specific issues related to cardiovascular disease. CMAJ. 2007; 176: S1– S44.Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Mallik S, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, Krumholz HM, Rumsfeld JS, Weintraub WS, Agarwal P, Santra M, Bidyasar S, Lichtman JH, Wenger NK, Vaccarino V; PREMIER Registry Investigators. Depressive symptoms after acute myocardial infarction: evidence for highest rates in younger women. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166: 876– 883.Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen Hasp Psychiatry. 2007; 29: 409– 416.Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Strauman T, Robins C, Newman MF. Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66: 305– 315.Google Scholar

22 Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F. Reflections on depression as a cardiac risk factor. Psychosom Med. 2005; 67( suppl 1): S19– S25.Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Pratt LA, Ford DE, Crum RM, Armenian HK, Gallo JJ, Eaton WW. Depression, psychotropic medication, and risk of myocardial infarction: prospective data from the Baltimore ECA follow-up. Circulation. 1996; 94: 3123– 3129.Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Parashar S, Rumsfeld JS, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, Wenger NK, Krumholz HM, Amin A, Weintraub WS, Lichtman J, Dawood N, Vaccarino V. Time course of depression and outcome of myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166: 2035– 2043.Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Carney RM, Freedland KE, Steinmeyer B, Blumenthal JA, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Czajkowski SM, Burg MM, Jaffe AS. Depression and five year survival following acute myocardial infarction: a prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2008; 109: 133– 138.Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Lane D, Carroll D, Ring C, Beevers DG, Lip GY. Mortality and quality of life 12 months after myocardial infarction: effects of depression and anxiety. Psychosom Med. 2001; 63: 221– 230.Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Lauzon C, Beck CA, Huynh T, Dion D, Racine N, Carignan S, Diodati JG, Charbonneau F, Dupuis R, Pilote L. Depression and prognosis following hospital admission because of acute myocardial infarction. CMAJ. 2003; 168: 547– 552.Google Scholar

28 Mayou RA, Gill D, Thompson DR, Day A, Hicks N, Volmink J, Neil A. Depression and anxiety as predictors of outcome after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2000; 62: 212– 2l9.Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Sorensenf C, Friis-Hasché E, Haghfelt T, Bech P. Postmyocardial infarction mortality in relation to depression: a systematic critical review. Psychother Psychosom. 2005; 74: 69– 80.Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Wassertheil-Smoller S, Applegate WB, Berge K, Chang CJ, Davis BR, Grimm R Jr., Kostis J, Pressel S, Schron E. Change in depression as a precursor of cardiovascular events: SHEP Cooperative Research Group (Systolic Hypertension in the elderly). Arch Intern Med. 1996; 156: 553– 561.Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Stein PK, Watkins L, Catellier D, Berkman LF, Czajkowski SM, O'Connor C, Stone PH, Freedland KE. Depression, heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001; 104: 2024– 2028.Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Taylor CB, Conrad A, Wilhelm FH, Neri E, DeLorenzo A, Kramer MA, Giese-Davis J, Roth WT, Oka R, Cooke JP, Kraemer H, Spiegel D. Psychophysiological and cortisol responses to psychological stress in depressed and nondepressed older men and women with elevated cardiovascular disease risk. Psychosom Med. 2006; 68: 538– 546.Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Pollock BG, Laghrissi-Thode F, Wagner WR. Evaluation of platelet activation in depressed patients with ischemic heart disease after paroxetine or nortriptyline treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000; 20: 137– 140.Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Serebruany VL, Glassman AH. Malinin AI, Sane DC, Finkel MS, Krishnan RR, Atar D, Lekht V, O'Connor CM. Enhanced platelet/endothelial activation in depressed patients with acute coronary syndromes: evidence from recent clinical trials. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2003; 14: 563– 567.Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Sherwood A, Hinderliter AL, Watkins LL, Waugh RA, Blumenthal JA. Impaired endothelial function in coronary heart disease patients with depressive symptomatology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46: 656– 659.Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N, Théroux P, Irwin M. The association between major depression and levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein in patients with recent acute coronary syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161: 271– 277.Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Empana JP, Sykes DH, Luc G, Juhan-Vague I, Arveiler D, Ferrieres J, Amouyel P. Bingham A, Montaye M, Ruidavets JB, Haas B, Evans A, Jouven X, Ducimetiere P; PRIME Study Group. Contributions of depressive mood and circulating inflammatory markers to coronary heart disease in healthy European men: the Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction (PRIME). Circulation. 2005; 111: 2299– 2305.Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Strik JJ, Denollet J, Lousberg R. Honig A. Comparing symptoms of depression and anxiety as predictors of cardiac events and increased health care consumption after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 42: 1801– 1807.Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F. Depression and anxiety as predictors of 2-year cardiac events in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008; 65: 62– 71.Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Carney RM, Freedland KB, Miller GE, Jaffe AS. Depression as a risk factor for cardiac mortality and morbidity: a review of potential mechanisms. J Psychosom Res. 2002; 53: 897– 902.Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Thomas AJ, Kalaria RN, O'Brien JT. Depression and vascular discase: what is the relationship? J Affect Disord. 2004; 79: 81– 95.Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I. Going to the heart of the matter: do negative emotions cause coronary heart disease? J Psychosom Res. 2000; 48: 323– 337.Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005; 26: 469– 500.Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Appels A. Depression and coronary heart disease: observations and questions. J Psychosom Res. 1997; 43: 443– 452.Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Gehi A, Haas D, Pipkin S, Whooley MA. Depression and medication adherence in outpatients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Arch Intent Med. 2005; 165: 2508– 2513.Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Rieckmann N, Kronish IM, Haas D, Gerin W, Chaplin WF, Burg MM, Vorchheimer D, Davidson KW. Persistent depressive symptoms lower aspirin adherence after acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2006; 152: 922– 927.Crossref, Google Scholar

47 DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160: 2101– 2107.Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients wilh depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160: 1818– 1823.Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Ades PA, Waldmann ML, McCann WJ, Weaver SO. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation participation in older coronary patients. Arch Intern Med. 1992; 152: 1033– 1035.Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Glazer KM, Emery CF, Frid DJ, Banyasz RE. Psychological predictors of adherence and outcomes among patients in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2002; 22: 40– 46.Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, Masson A, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Depression and health-care costs during the first year following myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res. 2000; 48: 471– 478.Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Stein MB, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Belik SL, Sareen J. Does co-morbid depressive illness magnify the impact of chronic physical illness? A population-based perspective. Psychol Med. 2006; 36: 587– 596.Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, Liu H, Browner WS, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: the Heart and Soul Study. JAMA. 2003; 29: 215– 221.Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Swenson JR. Quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease and the impact of depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004; 6: 438– 445.Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a call for recognition. Circulation. 2005; 111: 250– 253.Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343: 1942– 1950.Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16: 606– 613.Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; 22: 1596– 1602.Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Stafford L, Berk M, Jackson HJ, Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007; 29: 417– 424.Crossref, Google Scholar

60 McManus D, Pipkin SS, Whooley MA. Screening for depression in patients with coronary heart disease (data from the Heart and Soul Study). Am J Cardiol. 2005; 96: 1076– 1081.Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Davidson KW, Kupfer DJ, Bigger JT, Califf RM, Carney RM, Coyne JC, Czajkowski SM, Frank E, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Froelicher ES, Glassman AH, Katon WJ, Kaufmann PG, Kessler RC, Kramer HC, Krishnan KR, Lespérance F, Rieckmann N, Sheps DS, Suls JM. Assessment and treatment of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group report. Ann Behav Med. 2006; 32: 121– 126.Crossref, Google Scholar

62 US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Depression: Recommendations and Rationale. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002.Google Scholar

63 US Department of Health and Human Services; Public Health Service; Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Depression in Primary Care. Volume 1. Detection and Diagnosis. AHCPR Publication No. 93–0550. Rockville. Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993.Google Scholar

64 US Department of Health and Human Services; Public Health Service; Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Depression in Primary Care. Volume 2. Treatment of Major Depression. AHCPR Publication No. 93–0550. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993.Google Scholar

65 US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002; 36: 760– 764.Google Scholar

66 Patient Health Questionnaire Tool Kit for Clinicians. Available at: http://www.depression-primarycare.org/clinicians/toolkits/materials/forms/phq9.

67 Feinstein RE, Blumenfield M, Orlowski B, Frishman WH, Ovanessian S. A national survey of cardiovascular physicians' beliefs and clinical care practices when diagnosing and treating depression in patients with cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Rev. 2006; 14: 164– 169.Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Glassman AH, Bigger JT, Gaffney M, Shapiro PA, Swenson JR. Onset of major depression associated with acute coronary syndromes: relationship of onset, major depressive disorder history, and episode severity to sertraline benefit. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006; 63: 283– 288.Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Trivedi R, Johnson KS, O'Connor CM, Adams KF Jr, Dupree CS, Waugb RA, Bensimhon DR, Gaulden L, Christenson RH, Koch GG, Hinderliter AL. Relationship of depression to death or hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167: 367– 373.Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N, Koszycki D, Laliberté MA, van Zyl LT, Baker B, Swenson JR, Ghatavi K, Abramson BL, Dorian P, Guertin MC; CREATE Investigators. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial. JAMA. 2007; 297: 367– 379.Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT Jr, Krishnan KR, van Zyl LT, Swenson JR, Finkel MS, Landau C, Shapiro PA, Pepine CJ, Mardekian J, Harrison WM, Barton D, McIvor M; Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHEART) Group. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002; 288: 701– 709.Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Taylor CB, Youngblood ME, Catellier D, Veith RC, Carney RM, Burg MM, Kaufmann PG, Shuster J, Mellman T, Blumenthal JA, Krishnan R, Jaffe AS; ENRICHD Investigators. Effects of antidepressant medication on morbidity and mortality in depressed patients after myocardial infarction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62: 792– 798.Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Rieckmann N, Gerin W, Kronish IM, Burg MM, Chaplin WF, Kong G, Lespérance F, Davidson KW. Course of depressive symptoms and medication adherence after acute coronary syndromes: an electronic medication monitoring study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48: 2218– 2222.Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Glassman AH, Roose SP, Bigger JT Jr. The safety of tricyclic antidepressants in cardiac patients: risk-benefit reconsidered. JAMA. 1993; 269: 2673– 2675.Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N. What cardiologists need to know on depression in acute coronary syndromes. In: Theroux P, ed. Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2003: 131– 143.Google Scholar

76 Lett HS, Davidson J, Blumenthal JA. Nonpharmacologic treatments for depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2005; 67( suppl 1): S58– S62.Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ. Czajkowski SM, DeBusk R, Hosking J, Jaffe A, Kaufmann PG, Mitchell P, Norman J, Powell LH, Raczynski JM, Schneiderman N; Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients Investigators (ENRICHD). Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003; 289: 3106– 3116.Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Thase ME, Friedman ES, Biggs MM, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi MH, Luther JF, Fava M, Nierenberg AA, McGrath PJ, Warden D, Niederehe G, Hollon SD, Rush AJ. Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second step treatments: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2007; 164: 739– 752.Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Brosse AL, Sheets ES, Lett HS, Blumenthal JA. Exercise and the treatment of clinical depression in adults: recent findings and future directions. Sports Med. 2002; 32: 741– 760.Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on depression and its associated mortality. Am J Med. 2007; 120: 799– 806.Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Smith SC Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Fonarow GC, Grundy SM, Hiratzka L, Jones D, Krumholz HM, Mosca L, Pasternak RC, Pearson T, Pfeffer MA, Taubert KA; AHA/ACC; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006; 113: 2363– 2372.Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, Youngblood M. Veith RC, Burg MM, Cornell C, Saab PG, Kaufmann PG, Czajkowski SM, Jaffe AS; ENRICHD Investigators. Depression and late mortality after myocardial infarction in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66: 466– 474.Crossref, Google Scholar