Essential Ethical Skills of Mental Health Professionals

Abstract

(Reprinted with permission from Roberts LW, Hoop JG, Dunn LB, Geppert CM: Chapter 1: (pages 8-16) An overview for mental health clinicians, researchers, and learners. in Professionalism and Ethics. Roberts LW, Hoop JG (eds) 2008 American Psychiatric Publishing.)

Six essential skills

The clinical and interpersonal skills of the well-trained mental health professional ideally should translate into a facility with ethical problem solving—a sophisticated set of abilities that goes beyond a simple adherence to written guidelines, laws, and codes. Clinical training and, frequently, natural aptitude typically enable these clinicians to attend to subtleties and nuances, to look beyond the surface for hidden motivations, and to form habits of self-reflection and self-scrutiny. These skills and habits can form the basis for sensitivity to moral issues and an ability to solve ethical dilemmas in a systematic and thoughtful way.

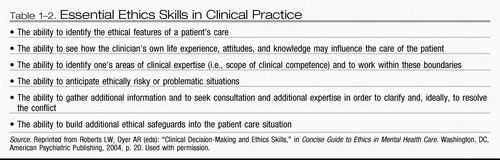

All mental health professionals whose work embodies the highest ethical standards tend to rely on a set of six core ethics skills that are learned during or before professional training and are continually practiced and refined during one's career (Roberts and Dyer 2004; Roberts et al. 1996a). These six skills are listed in Table 1–2. Acquiring these skills in support of professional conduct unites all the mental health disciplines in a common developmental process, with certain predictable issues and milestones that occur in relation to the nature of our work and societal roles with which we are entrusted (Fann et al. 2003; Hoop 2004; Roberts et al. 1996a).

|

Table 1–2. Essential Ethics Skills in Clinical Practice

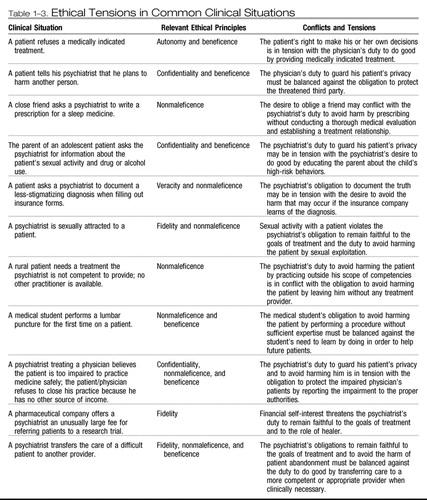

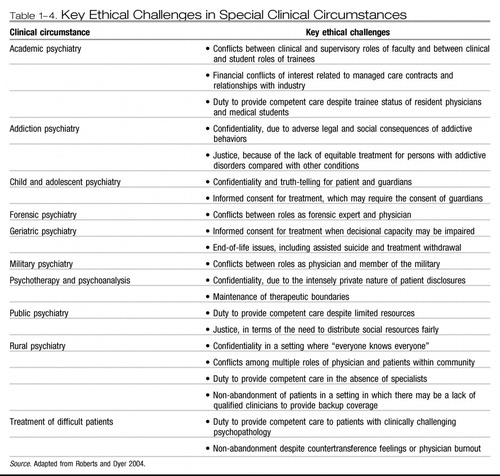

The first of these core skills is the ability to identify ethical issues as they arise. For some, this will be an intuitive insight (e.g., the internal sense that something is not right), and for others it will be derived more logically (e.g., the foreknowledge that involuntary treatment or the care of VIP patients poses specific ethical problems). Tables 1–3 and 1–4 outline some common ethical issues in mental health practice and related activities.

|

Table 1–3. Ethical Tensions in Common Clinical Situations

|

Table 1–4. Key Ethical Challenges in Special Clinical Circumstances

The ability to recognize ethical issues requires some familiarity with key ethics concepts and the emerging interdisciplinary field of bioethics. As a corollary, this ability presupposes the clinician's capacity to observe and translate complex phenomena into patterns, using the common language of the helping professions (e.g., conflicts among autonomy, beneficence, and justice when a person with mental illness threatens the life of a specific individual and is thus involuntarily held for evaluation).

The second skill is the ability to understand how the mental health professional's personal values, beliefs, and sense of self may affect his or her care of patients. Just as all clinicians involved in therapeutic work must be able to recognize and therapeutically manage transference and counter-transference in the doctor–patient relationship, they must also be able to understand how their own personalitiesand experiences may influence their ethical judgment. For instance, a psychiatric nurse who places a high value on her ability to do good as a healer should recognize that this may subtly influence her judgment when evaluating the decisional capacity of patients who refuse medically necessary treatments. A psychologist with a strong commitment to personal self-care and athleticism may have difficulty accepting patients who do not share this commitment and who engage voluntarily in high-risk behaviors with both ethical and clinical consequences. Attentiveness to these interpersonal aspects of the clinician-patient relationship is a crucial safeguard for ethical decision making by professionals in order to serve the needs and best interests of patients.

The third key ethics skill is an awareness of the limits of one's own medical knowledge and expertise and the willingness to practice within those limits. Providing competent care within the scope of one's expertise fulfills both the positive ethical duty of doing good as well as the obligation to do no harm. In some real-world situations, however, mental health professionals may at times feel compelled to perform services outside of their area of competence–for example, a general psychiatrist or psychologist providing care for elders or children due to the shortage of clinicians with subspecialty expertise. Such circumstances are often encountered in geographically isolated communities. For instance, rural providers may be faced with the dilemma of being asked to provide care for which they are not adequately trained or may treat people with whom they have other relationships (e.g., neighbors or local businesspeople). Rural practitioners may also be unable to provide care for all of the patients who need help (Roberts and Dyer 2004). In such settings, clinicians may feel ethically justified in choosing to do their best in the clinical situation, while simultaneously trying to resolve the underlying problem (American Psychiatric Association 2001b). For example, a rural psychologist may expand his or her zone of competence by obtaining consultation by telephone or using teleconferencing.

The fourth skill is the ability to recognize high-risk situations in which ethical problems are likely to arise. Such circumstances can occur when a mental health professional must step out of the usual treatment relationship to protect the patient or others from harm or to protect the patient's best interest (even when the patient may not agree). These situations include involuntary treatment and hospitalization, reporting child or elder abuse, and informing an identified third party of a patient's intention to inflict harm.

The fifth skill is the willingness to seek information and consultation when faced with an ethically or clinically difficult situation and the ability to make use of the guidance offered by these sources. All mental health professionals should tackle clinically difficult cases by reviewing the relevant literature and consulting with more (or differently) experienced colleagues. They should also strive to clarify and resolve ethically difficult situations by looking for data, referring to ethics codes and guidelines, discussing the circumstances with supervisors or consultants, and conferring with ethics committees when appropriate.

The sixth and final essential skill for the mental health professional is the ability to build appropriate ethical safeguards into one's work. For example, clinicians who treat children and adolescents should routinely inform new patients and their parents at the initiation of treatment about limits of confidentiality and the clinician's legal mandate to report child abuse (Belitz 2004). Similarly, clinical researchers can prevent some ethical conflicts from arising in the course of their research by designing protocols that incorporate safeguards, such as careful training for research staff, participant education sessions in conjunction with the informed consent process, operating procedures that protect personal information gathered from study volunteers (e.g., data encryption), and a priori exit criteria for with-drawing participants (Roberts 1999).

Practical ethical problem solving

Many clinicians use an eclectic approach to ethical problem solving that makes intuitive use of principles, case experiences, lessons learned from colleagues, and a combination of inductive and deductive reasoning. Such an approach does not typically yield one “right” answer but, rather, an array of possible and ethically justifiable responses that may be acceptable in the specific set of circumstances. For lower-risk decisions (e.g., introducing a new medication into the care of a reluctant patient this visit vs. the next visit), this style of decision making is often quite adequate. For higher-risk decisions that must now-or may later have to-stand up to more rigorous scrutiny, a more systematic and explicit approach is better and often necessary.

In the clinical setting, a widely used approach to ethical problem solving is the four-topics method described by Jonsen and colleagues (2002). This method entails gathering and evaluating information about 1) clinical indications, 2) patient preferences, 3) patient quality of life, and 4) contextual or external influences on the ethical decision-making process. The model for this approach is depicted in Figure 1–1.

Source. Reprinted from Roberts LW, Dyer AR (eds): “Health Care Ethics Committees,” in Concise Guide to Ethics in Mental Health Care. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004, p. 307. Used with permission.

This four-topics methodology has the advantage of being pragmatic, offering an implicit prioritization of issues that arise in complex, real-world situations, and having been successfully utilized to analyze ethical issues in a variety of clinical settings and decision contexts. The approach has been widely disseminated, and many ethics committees in hospitals use the model in their evaluations and decisions regarding ethical dilemmas. In the psychiatric context, less attention has been paid to developing ethical decision-making models specifically addressing the unique characteristics of psychiatric patients, settings, and decisions (Roberts et al. 1996a). With practice, however, the four-topics method can be used to help psychiatrists and other mental health professionals think through both straightforward and complex ethical cases. Strategies for systematically evaluating ethical issues in clinical supervision of multidisciplinary colleagues and clinicians in training may also be helpful in academic and community-based patient care settings (Roberts et al. 1996b).

Many ethical dilemmas in clinical care involve a conflict between the first two topics of the four-topics model: clinical indications and patient preferences (Table 1–3). Consider, for instance, a severely depressed elder with cancer who refuses life-prolonging chemotherapy, or an adolescent who is experiencing psychotic symptoms, is behaviorally erratic, and is brought to a hospital against his will. Other scenarios include a psychologist attempting to form a therapeutic alliance with an individual who has received inadequate treatment in the past or a psychiatric social worker evaluating a young mother who refuses a life-saving blood transfusion on religious grounds. In each scenario, the patient's preferences are crosswise with what is deemed medically beneficial, creating a conflict between duties of beneficence (promoting patient welfare) and respecting patient autonomy (respecting patient wishes).

In order to work through such dilemmas where two vital ethical principles are at odds one must first explore fully and thoughtfully the patient's preferences as well as the clinical indications. Why does the patient refuse treatment? Does the patient have the cognitive and emotional capacity to make this decision at this time? Is there a range of options, perhaps ones that had not been previously considered, that may offer benefit? How urgent is the clinical situation, and is time available for discussion, collaboration, and perhaps compromise? If the patient does not have decision-making capacity, the dilemma is at least temporarily resolved by identifying an appropriate alternative decision-maker. If the patient does have the ability to provide informed consent–involving capacity for decision making (Appelbaum and Grisso 1988) and capacity for voluntarism (Geppert 2007b; Roberts 2002b)–then, under most foreseeable circumstances, his or her preferences must be followed. However, by engaging the patient in a meaningful dialogue in which the mental health professional describes the full range of treatment options and demonstrates sensitivity to the reasons for the patient's refusal, it may often be possible to discover a solution that the patient can willingly accept and the clinician can justify as medically beneficial.

Roberts LW, Dyer A: A Concise Guide to Ethics in Mental Health Care. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004Google Scholar

Roberts LW, McCarty T, Roberts BB, et al: Clinical ethics teaching in psychiatric supervision. Acad Psychiatry 20: 176– 188, 1996aCrossref, Google Scholar

Fann JR, Hunt DD, Schaad D: A sociological calendar of transitional stages during psychiatry residency training. Acad Psychiatry 27: 31– 38, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Hoop JG: Hidden ethical dilemmas in psychiatric residency training: the psychiatry resident as dual agent. Acad Psychiatry 28: 183– 189, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association: Opinions of the Ethics Committee on the Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry, 2001 Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001bGoogle Scholar

Belitz J: Caring for children, in Concise Guide to Ethics in Mental Health Care. Edited by Roberts LW, Dyer AR. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004, pp 119– 135Google Scholar

Roberts LW: Ethical dimensions of psychiatric research. A constructive criterion based approach to protocol preparation: the Research Protocol Ethics Assessment Tool (RePEAT). Biol Psychiatry 46: 1106– 1119, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ: Clinical Ethics: A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine, 5th Edition. New York, McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division, 2002Google Scholar

Roberts LW, Hardee JT, Franchini G, et al: Medical students as patients: a pilot study of their health care needs, practices, and concerns. Acad Med 71: 1225– 1232, 1996bCrossref, Google Scholar

Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: Assessing patients' capacities to consent to treatment. N Eng J Med 319: 1635– 1638, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

Geppert CM: Voluntarism in consultation psychiatry: the forgotten capacity. Am J Psychiatry 164: 409– 413, 2007bCrossref, Google Scholar

Roberts LW: Informed consent and the capacity for voluntarism. Am J Psychiatry 159: 705– 712, 2002bCrossref, Google Scholar