The Effect of Family Interventions on Relapse and Rehospitalization in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

Twenty-five intervention studies were meta-analytically examined regarding the effect of including relatives in schizophrenia treatment. The studies investigated family intervention programs to educate relatives and help them cope better with the patient’s illness. The patient’s relapse rate, measured by either a significant worsening of symptoms or rehospitalization in the first years after hospitalization, served as the main study criterion. The main result of the meta-analysis was that the relapse rate can be reduced by 20 percent if relatives of schizophrenia patients are included in the treatment. If family interventions continued for longer than 3 months, the effect was particularly marked. Furthermore, different types of comprehensive family interventions have similar results. The bifocal approach, which offers psychosocial support to relatives and schizophrenia patients in addition to medical treatment, was clearly superior to the medication-only standard treatment. The effects of family interventions and comprehensive patient interventions were comparable, but the combination did not yield significantly better results than did a treatment approach, which focused on either the patient or the family. This meta-analysis indicates that psychoeducational interventions are essential to schizophrenia treatment.

The past decade has witnessed a growing interest in psychoeducation and family participation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Because of improved medication treatment in the past 40 years, more patients can be treated today in an outpatient setting and the majority of the patients stay with their families (Schooler et al. 1995). Caring for a schizophrenia patient is often a burden for families. About two-thirds of the family caregivers feel considerably burdened (Creer and Wing 1974; Hatfield 1978; Fadden et al. 1987; Kuipers 1993; Winefield and Harvey 1993). Relatives involved are experiencing severe emotional and economic strain and often suffer from various health problems. Families with a member afflicted with such a serious illness need help to cope with this burden and related personal stress.

Several surveys indicate that relatives need more information about the disease and how to deal with it more effectively. The research of Brown and coworkers (1958, 1962, 1972) and the further work of Leff and Vaughn on the concept of “expressed emotion” (Vaughn 1986) strongly support the importance of psychoeducational work with relatives of schizophrenia patients. In theory and practice, the approach to caring for relatives has gradually changed during the past two decades. Relatives of schizophrenia patients are no longer stigmatized as having caused the illness; rather, they are considered partners in treatment who need the proper tools. Mental health professionals have hoped that well-informed relatives could act as co-therapists (Lefley and Johnson 1990; Böker 1992; Bäuml 1993) and might thus help to improve patients’ compliance (Corrigan et al. 1990; Kissling 1994).

As a result, various family intervention programs were developed, such as family therapy in a single-family setting (Esterson et al. 1965; Goldstein et al. 1978; Falloon et al. 1984; Tarrier et al. 1988; Hogarty et al. 1991) or in a multifamily setting (McFarlane et al. 1995a, 1995b), psychoeducational relatives’ groups (Leff et al. 1990; Posner et al. 1992; Bäuml et al. 1996), educational lectures for relatives (Smith and Birchwood 1987; Tarrier et al. 1988; Canive et al. 1993), counseling groups for relatives (Vaughan et al. 1992; Szmukler et al. 1996; Buchkremer et al. 1997), and group therapy for relatives (Schindler 1958; Köttgen et al. 1984; Lewandowski and Buchkremer 1988). Most of these interventions for relatives can be subsumed under the category of “psychoeducation” or at least contain psychoeducation as an essential component. “Psychoeducation” is the most common collective designation for an intervention that combines the imparting of information with therapeutic elements, and the term is internationally acknowledged.

Despite the positive results substantiated by numerous intervention studies, the inclusion of relatives in the treatment of schizophrenia patients is still not an integral part of routine procedures in many countries. This may result from the initial work involved in establishing such intervention programs as well as general skepticism about the effectiveness of such psychosocial treatment forms. Research results need to be summarized to determine the exact treatment effects achieved through family interventions. In previous narrative reviews (Barrowclough and Tarrier 1984; Strachan 1986; Waring et al. 1986; Tarrier 1989; Falloon et al. 1990; Smith and Birchwood 1990; Bellack and Mueser 1993; Dixon and Lehman 1995; Penn and Mueser 1996), the quantitative analysis was restricted to the representation of the various statistical significances of the individual studies or to counting the studies with significant results. Thus, information contained in the primary literature was not fully exploited. Meta-analytic reviews are needed to assess quantitatively the efficacy of family interventions and to summarize the current state of scientific knowledge in this field. The first carefully conducted meta-analysis, by Mari and Streiner (1994), demonstrated a moderate effectiveness of family interventions in schizophrenia. The result was based on six primary studies investigating community-oriented family interventions of more than five sessions. Updates of this meta-analysis (Mari and Streiner 1996; Pharoah et al. 1999) containing up to 13 studies confirmed the result that family interventions may decrease the frequency of relapse and rehospitalization and that they may encourage compliance (Pharoah et al. 1999). But the authors point out that further data are needed to consolidate these findings.

In our meta-analysis, some more studies (studies published up to 1997) could be added and the following questions were studied in detail:

| • | Is treatment that includes relatives superior to the usual care? | ||||

| • | Do the treatment effects differ for followup periods of different lengths? | ||||

| • | Do characteristics of the studies such as duration of intervention, type of intervention, study criteria, and study sample influence the treatment effects? | ||||

| • | Does the combination of family intervention and patient intervention produce better results than family intervention alone? | ||||

| • | Is family intervention superior to psychosocial patient intervention? | ||||

| • | Which type of family intervention achieves the best results? | ||||

Method

Identification and selection of studies

A computerized literature search was performed using the data base Medline (1966–December 1997) and the keywords 11 schizophrenia,” “family,” “psychoeducation,” and “relapse.” In addition, reference lists of previous reviews on the subject as well as references of other relevant articles were sources of information. Only English and German studies were selected. Number of patients who relapsed and number of patients who required rehospitalization were used as outcome parameters. Thus, studies that investigated interventions on the relatives of schizophrenia patients but focused on other study criteria, such as knowledge increase of the relatives or reduction of burden and stress, were not considered. After carefully screening about 600 articles, 39 potentially suitable studies were selected.

| • | All these studies were coded with respect to relevant variables corresponding to the suggestions by Chalmers and coworkers (1981). The quality of each study was rated “good,” “sufficient,” or “insufficient.” For this global rating, the quality of the study design, the presentation of the results, and the statistical analyses were taken into account. Nonrandomized studies were generally considered “insufficient.” Studies that received an “insufficient” for quality were excluded. | ||||

| • | To verify the reliability of the coding system, we recruited a second coder who was a specialist in meta-analyses but not family interventions. Differing assessments and uncertainties were discussed and final agreement was established. A survey of the coding variables and the final coding of the individual studies may be obtained from the authors on request. | ||||

Data analyses

The relapse rates or rehospitalization rates achieved in the studies under the respective treatment conditions served as a basis for the present meta-analytical calculations. Several methods for the calculation of effect sizes are available, but they generally do not yield greatly different results (Rosenthal 1991). In this meta-analysis phi (ϕ) was calculated as an effect size estimate according to the formula  , which corresponds to Pearson’s correlation coefficient r applied to dichotomous data. This effect size was applied because it is easy to interpret using the binomial effect size display method (BESD: defined as a change from 0.5–r/2 to 0.5+r/2), developed by Rosenthal and Rubin (1982). All calculations were performed according to the procedures proposed by Rosenthal (1991), which are acknowledged and often used in social and medical research (Bennett Herbert and Cohen 1993; Butzlaff and Hooley 1998; Leucht et al. 1999). The effect sizes were transformed into Fisher’s zr values. The mean effect size r̄ was then calculated from z̄r, the weighted mean of the zr values. All pooled calculations included a test of heterogeneity using χ2 tests. For the indirect comparison of two mean effect sizes with regard to a hypothesis, contrast weights were calculated.

, which corresponds to Pearson’s correlation coefficient r applied to dichotomous data. This effect size was applied because it is easy to interpret using the binomial effect size display method (BESD: defined as a change from 0.5–r/2 to 0.5+r/2), developed by Rosenthal and Rubin (1982). All calculations were performed according to the procedures proposed by Rosenthal (1991), which are acknowledged and often used in social and medical research (Bennett Herbert and Cohen 1993; Butzlaff and Hooley 1998; Leucht et al. 1999). The effect sizes were transformed into Fisher’s zr values. The mean effect size r̄ was then calculated from z̄r, the weighted mean of the zr values. All pooled calculations included a test of heterogeneity using χ2 tests. For the indirect comparison of two mean effect sizes with regard to a hypothesis, contrast weights were calculated.

Results are presented as (mean) effect sizes along with their 95 percent confidence interval (CI), with positive values indicating effects in favor of the family intervention. Two-tailed significance tests were used, and for the evaluation of the results a significance level of 5 percent was taken as the basis.

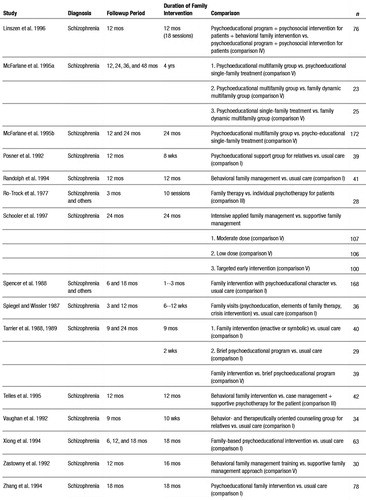

Studies with repeated measurement

Several studies provided results for two or more followup periods (table 1). Several effect sizes were calculated for each of these studies. The first-year effect size refers in each case to the last assessment within the first year after the treatment; the second-year effect size refers to the assessment period within the second year; and so on. For each year, a mean effect size was calculated. When calculating the overall mean effect sizes, the mean values of the repeated measurements were entered. In the comparison of different followup periods, only the last value of a study was used to ensure independent measurement.

Treatment of dropout patients

Because dropout patients could not always be associated with the treatment groups involved in the individual comparisons, the figures were used uniformly following the according-to-protocol (ATP) strategy. Two studies (Spencer et al. 1988; Kelly and Scott 1990) indicated the relapse rates of study completers, which were used as a basis for the calculations. In the study of Tarrier et al. (1989) the effect sizes for the second year were likewise calculated on the basis of the study completers only.

Results

Fourteen intervention studies had to be excluded because their quality was rated “insufficient.” Four studies (Bäuml et al. 1991; McCreadie et al. 1991; Schneider et al. 1991; Boonen and Bockhorn 1992; McCreadie 1992) provided no control group, nine studies lacked a randomized assignment to one of the treatment conditions (Schindler 1958; Esterson et al. 1965; Snyder and Liberman 1981; Köttgen et al. 1984; Ehlert 1988; Lewandowski and Buchkremer 1988; MacCarthy et al. 1989; Scherrmann and Seizer 1989; Scherrmann et al. 1992; Rund et al. 1994), and in one study data for group comparisons were missing (Levene et al. 1989, 1990).

The selected studies enabled us to establish five basic categories for comparisons.

1. Comparison I: Family intervention vs. usual care. Studies testing a family intervention against standard treatment are included here. As comparison I encompasses a sufficient number of studies, contrast analyses could be performed.

2. Comparison II: Family intervention + patient intervention vs. usual care. Studies that combined a family intervention with a psychosocial patient intervention and tested this intervention package against the standard treatment are included in this category.

3. Comparison III: Family intervention vs. patient intervention. Studies that compared family intervention to patient-oriented psychosocial intervention are part of this category.

4. Comparison IV: Family intervention + patient intervention vs. patient intervention. Studies that investigated what additional effects family intervention has compared to mere psychosocial patient intervention fall within this category.

5. Comparison V: Family intervention A vs. family intervention B. Studies that compared two different family intervention programs appear in this category.

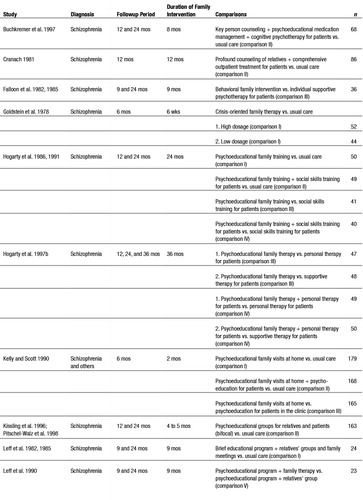

Seven studies were based on more than two intervention strategies (i.e., different types of family interventions or different medication strategies). Because studies with more than two treatment conditions cannot be reasonably summarized under one specific hypothesis, these studies were included several times in the meta-analysis. Either partial samples were assigned to different comparisons (Tarrier et al. 1988, 1989; Kelly and Scott 1990; Hogarty et al. 1991; Hogarty et al. 1997b) or the studies were included twice in a single comparison with two different partial samples (Goldstein et al. 1978; Tarrier et al. 1988, 1989; McFarlane et al. 1995a; Schooler et al. 1997). In the final stage, 25 studies with a total of 40 individual comparisons were included in the meta-analysis. Some important variables of the studies are shown in table 1.

Description of studies

All of the studies included were conducted between 1977 and 1997. In the majority of the studies family interventions were performed in outpatient settings (62%). The sample sizes of the studies varied from n=23 to n=418. The average age of the patients in the individual studies lay between 16 and 40 years. Approximately one-third of the patients included were female. The percentage of females ranged from 0 to 65 percent. Patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective psychoses were included. Four studies also relied on patients with different diagnoses according to one of the established diagnostic systems. The study patients included those with first episodes and those with multiple episodes. The average number of hospital stays of the patients per study was between 1 and 7. The relatives included in the treatment were usually the patient’s parents (range: 50%–100%). In four studies only high EE (“Expressed Emotion” status assessed with the Camberwell Family Interview) families were involved. With the exception of the study of Schooler et al. (1997), who tested different medication strategies, and the study of Goldstein et al. (1978), who varied the dose of the antipsychotic treatment, family and patient interventions were carried out in addition to the standard medication treatment (antipsychotic relapse prevention). The duration of the family interventions ranged from 2 weeks to 4 years. Most of the family interventions studied were classified as psychoeducational. The psychosocial patient interventions in the comparative studies included psychoeducational interventions, social skills training, supportive or cognitive psychotherapy, and personal therapy. Because the selected studies and their intervention programs have already been described in numerous reviews (Mosher and Keith 1980; Barrowclough and Tarrier 1984; McGill and Lee 1986; Schooler 1986; Waring et al. 1986; Falloon et al. 1990; Smith and Birchwood 1990; Tarrier and Barrowclough 1990; Lam 1991; Bellack and Mueser 1993; Dixon and Lehman 1995; Goldstein 1995, 1996a; Penn and Mueser 1996; Schaub and Brenner 1996), a more detailed description of each study has been omitted in this article. The interested reader may refer to the original literature and the reviews.

Family intervention vs. usual care (comparison I)

The effect sizes from 12 different studies (of 14 individual comparisons) were compared with each other. The heterogeneity test was not significant. A mean effect size r̄=0.20 (p<0.0001; Cl=0.14–0.27) was calculated in the comparison of family intervention and usual care. A treatment that includes family intervention is clearly superior to the usual care of schizophrenia patients.

Table 2 shows the studies included, the relapse rates for the first and second years, and the result of the effect size calculations.

Different followup periods

The effect sizes were examined 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months after treatment. The differences between the mean effect sizes independently measured during these five different followup periods were not statistically significant (r̄6 months=0.16, r̄9 months=0.24, r̄12 months=0.07, r̄18 months=0.24, r̄24 months=0.26, r̄total=0.20; χ2=3.45; p>0.1). The success rate remained approximately the same at all points in time within the first 2 years after treatment as long as relatives were included in the treatment strategy.

Duration of family interventions

It was investigated whether short-term interventions (interventions lasting less than 3 months) were just as effective as interventions of longer duration. The group of short-term interventions included seven studies (table 1) with a treatment duration of 2 to 10 weeks. The group of long-term interventions encompassed six studies with a treatment duration of 9 to 24 months. The effect sizes within both types of interventions were homogeneous. As shown in table 3, a mean effect size of 0.14 (CI=0.06–0.22) was found for short-term interventions. For long-term interventions the mean effect size was 0.30 (CI=0.19–0.41). Both short-term and long-term family interventions in addition to the usual care were superior to standard medical care alone (p<0.005 and p<0.0001). However, long-term interventions appeared to be more successful (z=2.36; p<0.05) than short-term interventions.

Type of family interventions

We tested whether the type of family intervention had any influence on the effect size. For this analysis, each study was assessed as to whether the family intervention was more psychoeducationally or more therapeutically oriented. A mean effect size of 0.18 (CI=0.11–0.26) was calculated for psychoeducational interventions. For therapeutic interventions the mean effect size was 0.23 (CI=0.10–0.36). No matter whether the interventions were psychoeducationally or therapeutically oriented, significantly better results were attained through additional family interventions than with the usual standard medical care (p<0.0001 and p<0.001). Even though the mean effect size for therapeutically oriented interventions was greater in magnitude, the contrast calculation proved that the type of family intervention did not significantly influence the effect size (z=0.61; p>0.5).

Study criteria

We examined whether different definitions of the study criterion also led to different results. We averaged the effect sizes of studies that used worsening of the patient’s symptoms as a criterion for the relapse rate. The effect sizes of studies that used rehospitalization as a criterion were combined separately. In studies with two criteria (worsening of symptoms, rehospitalization), the figures for rehospitalization were selected preferentially. As listed in table 3. the mean effect sizes were similar in magnitude: 0.20 (p<0.001; CI=0.09–0.30) and 0.19 (p<0.0001; CI=0.11–0.28). The calculated z value was not significant (z=0.09; p>0.5).

Sample selection

In most of the studies the sample consisted solely of patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective psychosis (according to DSM-III, DSM-III-R, Present State Examination, ICD-9, Research Diagnostic Criteria, and other diagnostic systems). In two cases interventions were also offered to relatives of patients with other diagnoses. To check whether this difference in sample composition had any impact on the effect size, the mean effect size of all studies based on a sample of only schizophrenia patients was contrasted with the mean effect size of those studies with mixed samples. As shown in table 3, a mean effect size of 0.24 (p<0.0001; Cl=0.17–0.29) was calculated for the studies with only schizophrenia patients. The mean effect size of studies with mixed samples was 0.12 (p<0.05; CI=0.02–0.23). Significant effects resulted for both sample types. The mean effect size of the studies with schizophrenia patients only was higher, but contrast calculations failed to be statistically significant (z=1.75; p=0.08).

Family intervention + patient intervention vs. usual care (comparison II)

In comparison II the effectiveness of combined interventions for schizophrenia patients and their relatives was tested and compared to administering only standard medical care. Five studies were part of comparison II. Calculations were based on a total of 523 patients.

Table 4 lists the studies that fall into this category, the relapse rates for the first and second years, and the calculated effect sizes.

Combining effect sizes

Combining the five calculated effect sizes yielded a mean effect size of r̄=0.18 (p<0.0001; CI=0.16–0.29). As expected, the bifocal approach offering support to relatives as well as schizophrenia patients turned out to be more successful than the simple drug treatment of schizophrenia alone.

Independent measurements for the two different followup periods indicated that the mean effect size for the second year (r̄=0.23; p<0.0001; CI=0.12–0.33) was greater than in the first year (r̄=0.13; p=0.03; CI=0.04–0.25).

Bifocal vs. unifocal approach

We wanted to know whether the combination family intervention + patient intervention yielded better results than family intervention alone (without special psychosocial intervention on behalf of the patient). For this purpose, an indirect comparison was carried out by means of contrasts of Fisher’s z’s. The difference between the weighted mean effect size of comparison I (r=0.20) and the weighted mean effect size of comparison II (r=0.18) proved to be statistically nonsignificant (z=0.47; p>0.5). The effects of combined interventions were comparable to those of a family intervention not accompanied by a special patient intervention.

Family intervention vs. patient intervention (comparison III)

In comparison III the question was asked whether family interventions might lead to a lower relapse rate than interventions solely focusing on the schizophrenia patients and excluding relatives. Six studies were part of this group and included a total of 40 patients. Table 5 lists all studies included; the relapse rate for the first, second, and third years; and the calculated effect sizes.

Combining effect sizes

The averaging process the effect sizes resulted in a value of r̄=0.01 (p>0.5; CI=–0.09–0.11). Thus, the effect of a family intervention seems to be comparable to that of an intervention addressed directly to the patients. When it comes to drawing conclusions one should proceed with caution, because only a small number of studies were conducted in this field and each of the studies was quite different. Averaging the effect sizes of these studies produced strong heterogeneity (χ2=35.1; df=6; p<0.001). There were three studies with a result clearly in favor of the family intervention, one study with no difference between family and patient interventions, and two studies with a result clearly in favor of the patient intervention.

Different followup periods

The mean effect sizes for the three defined measurement periods were calculated based on independent sampling. Whereas the effects of the interventions with families and with patients did not differ al all during the first year (r̄=0.00; p=1.0; Cl=–0.13–0.12), a highly significant difference was found during the second year after discharge (r̄=0.46; p<0.0001; Cl=0.26–0.62). For the third year a significant result in favor of the patient intervention was calculated (r̄=–0.28; p<0.0001; Cl=–0.48–0.05).

These results must also be interpreted with caution because the effect sizes are largely heterogeneous in the first (χ2=14.6; df=2; p<0.001) and second year (χ2=6.09; df=1; p<0.05) and the number of studies available varies across the followup periods. Although family interventions on behalf of schizophrenia patients seem to be as successful as patient interventions during the first year, the second year after discharge shows a different picture. Here it becomes apparent how effective family interventions can be and that such measures actually reduce the relapse rate among schizophrenia patients significantly. On the other hand the latest Hogarty et al. (1997b) study, which provided the only data for the third year, demonstrated the superiority of personal therapy, a comprehensive patient intervention, over the family intervention.

Family intervention + patient intervention vs. patient intervention (comparison IV)

Hogarty et al. (1991, 1997b) and Linszen et al. (1996) investigated additional effects of family interventions. All study patients received comprehensive psychosocial treatment, and some of them were subject to a family intervention. Table 6 lists all studies included; the relapse rates for the first, second, and third years; and the calculated effect sizes.

Combining effect sizes

The mean effect size calculation produced an r of 0.04 (p>0.5; Cl=–0.10–0.17). After 1, 2, and 3 years no difference in results was detected for the two treatment conditions. Thus, no additional effect of a family intervention could be found, on condition that the patients received a comprehensive treatment.

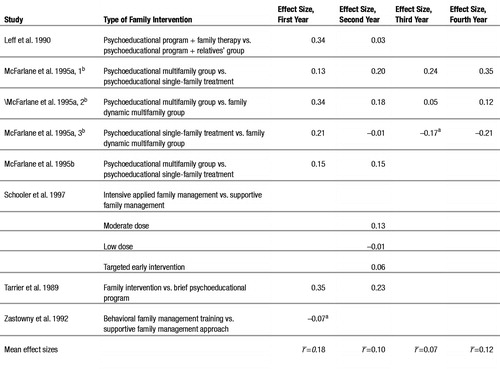

Family intervention A vs. family intervention B (comparison V)

Several research groups set out to investigate which form of family intervention is most effective. They conducted comparative studies on the topic—mostly without involving a control group. Six studies could be assigned to comparison V, which included data of 659 patients. Table 7 lists all studies included, the different types of family intervention that were tested, and the calculated effect sizes.

Combining effect sizes

Although very different types of interventions were tested, we tried to combine them under one single explicit hypothesis. What the studies had in common was that the authors wanted to investigate whether there is a significant difference between family interventions that differ in their intensity. Thus, more and less intensive interventions were compared. An overall mean effect size of r̄=0.10 (p<0.01; Cl=0.03–0.18) resulted. This indicates that a more intensive family treatment approach is statistically significantly superior to a more limited approach. Taking a closer look at the individual studies, it can be concluded for comparison V that good results were obtained with comprehensive interventions of different types. Differences in the effect sizes of family interventions refer to the studies testing brief interventions, which made in general a poorer showing, and studies testing the multifamily format, which seems to be more successful in the long run than the single-family approach.

Discussion

This meta-analysis clearly indicates that including the relatives in treatment programs is an effective way of reducing relapse and rehospitalization rates in schizophrenia patients. The mean effect size of 0.20 attained in this meta-analysis appears low in numerical terms but should be considered quite substantial when compared to the question posed. We are aware of the difficulty of interpreting a meta-analytic effect size. For a better understanding we can use BESD. The r̄ of 0.20 would correspond to a decrease in relapse rate of 20 percent. An average relapse rate of 60 percent thus can be reduced to about 40 percent. This definitely is an important finding of clinical relevance. However, some points require a more detailed discussion.

Duration of family interventions

The differentiated analysis of treatment effects in comparison I revealed that the effect size varied depending on the duration of the interventions. The success of family interventions was particularly evident when these interventions lasted longer than 3 months. Not only in this contrast analysis but also in comparison V of this meta-analysis, where various forms of family interventions were directly compared, brief interventions proved inferior. It was clearly demonstrated that a few lessons on schizophrenia for relatives was simply not sufficient to substantially influence the relapse rate. These findings are in line with the conclusions drawn by Fiedler et al. (1986), Tarrier and BarrowcIough (1990), and Mari and Streiner (1994), and they confirm Hogarty’s criticism of the Videka-Sherman meta-analysis (Hogarty 1989). The author of the meta-analysis (Videka-Sherman 1988) had concluded that brief psychosocial interventions including family interventions are more effective than long-term interventions. Hogarty (1989) argued that low-quality studies might have unduly influenced this result and pointed out that data from better designed studies lead to the opposite conclusion.

Type of family interventions

In comparison I it was indirectly examined whether psychoeducational interventions are just as effective as intensive therapeutic interventions. When grouping effect sizes according to the type of intervention no statistically significant difference was found. Closer inspection revealed that the effects were confounded with those of the variable duration. The somewhat lower mean effect size for psychoeducational interventions particularly derived from studies that performed a brief psychoeducational intervention, whereas long-term psychoeducational interventions such as those of Hogarty et al. (1991) or Leff et al. (1985) yielded large effect sizes. On the whole the long-term participation of relatives in the treatment of schizophrenia patients proved very successful, with the type of intervention being rather secondary. An explanation of this finding could be that general therapeutic factors as defined for example by Yalom (1984) for group psychotherapy may also become effective in psychoeducational interventions over time.

The results of the contrast analyses (comparison I) were confirmed by comparison V. where various forms of family interventions were directly compared. Taking the studies together it turned out that there are significant differences in the effectiveness of family interventions. Again, long-term interventions appeared to be more effective. Under the condition that they are long-term interventions, the psychotherapeutic intensity or orientation seems to be secondary. Comparison V adds another interesting finding concerning the format of family interventions. In the two McFarlane et al. studies (1995a, 1995b) the multi-family approach yielded better results than the treatment in a single-family setting. However, conclusive results on this issue can be derived only from future studies.

Methodological variables of family intervention studies

The impact of methodological variables of the studies on the effect sizes was also investigated in this meta-analysis (comparison I). Criteria were selected such as followup period, study criterion, and choice of sample (which had been discussed as influencing variables in the relevant literature) to analyze their specific influence on the effect sizes in intervention studies in more detail. Considering followup period, several authors hypothesized that the effectiveness of family interventions would be visible more clearly during later measurements, for example, during the second year after the intervention took place. This assumption was based on the results of the Hogarty et al. (1991) and Falloon et al. (1985) studies. The meta-analysis revealed that the treatment effects did not differ significantly for followup periods of different lengths. The question of whether the effect size remains the same for followups beyond the 24-month followup cannot yet be answered adequately. Hogarty et al. (1991) found some evidence that family intervention effects do not persist long after the treatment ends. On the other hand, two recent studies (Bäuml et al. 1997; Hornung et al. 1999) provided positive results concerning the long-term effects achieved through bifocal interventions. The rehospitalization rates in both studies increased with the number of years, but the difference between the intervention group and the control group remained constant. The 5- and 8-year followup data of Tarrier et al. (1994) also support the positive long-term effects of family interventions. Thus, psychoeducational family interventions may have a positive effect not only during the treatment and shortly afterward but also months and years thereafter. To get a definite answer to this question, more long-term studies are needed. In addition, further studies should investigate whether regular booster sessions can help to stabilize the effects of psychoeducational family interventions over a longer period of time.

The impact of another criterion, the study criterion, was investigated because one group of intervention studies classified the worsening of symptoms as a relapse, whereas another group used rehospitalization as an essential outcome criterion. The literature supports both variants. However, rehospitalization has become a dominant criterion in today’s research, as it is easy and clear to measure. The effect size did not vary in dependence on the study criterion. This means that family interventions did not only improve the competence of relatives in dealing with the patients, implying that fewer rehospitalizations became necessary due to acute crises, but did actually decrease the occurrence of acute crises considerably.

Separate averaging of the effect sizes for different samples (schizophrenia/mixed diagnoses) indicated that the mean effect size tended to be higher for homogeneous schizophrenia samples than for diagnostically heterogeneous samples. It definitely makes sense in all cases of psychiatric illnesses to include the patient’s relatives in the treatment process, to provide them with information about the illness and explain specific psychosocial aids to them. Because patients suffering from schizophrenia are particularly dependent on the support of their families, it is important to enhance the involvement of relatives and to test its effectiveness. It can be concluded from the results of this meta-analysis that family interventions are particularly effective when they are tailored directly to the needs of this special target group. If such interventions are offered only to relatives of schizophrenia patients, therapists can go into detail on their specific problems more intensively. Participants might benefit better from this type of intervention than from interventions that cover the entire spectrum of questions and problems concerning various psychiatric diseases in the same number of sessions.

It is also important to remember that the average relapse rate observed during the first followup year might be lower for patients with diagnoses other than schizophrenia. Therefore, the actual margin for a reduction in this rate was less to start with.

The impact of family interventions in comparison to psychosocial patient interventions

Even though some studies suggest an additive effect of family intervention and patient intervention (Kelly and Scott 1990; Hogarty et al. 1991; Bäuml et al. 1997; Buchkremer et al. 1997), the indirect comparison (comparison II) did not prove that. Bifocal intervention approaches did not produce a significantly greater effect size than family interventions alone. This does not mean that a psychosocial intervention focused on the schizophrenia patient alone has no positive effect on the relapse rate. When effect sizes were combined in comparison III, the results of patient interventions were comparable to the results of family interventions. The effect sizes of the individual studies, however, were very heterogeneous. Three studies showed the superiority of family interventions, one study found no difference, and two studies brought better results under the patient intervention condition. The reason for this heterogeneity may be that there are differences in the effectiveness of the individual patient intervention approaches. Whereas in a previous meta-analysis on social skills training only moderate effects on the relapse rate were found (Benton and Schroeder 1990), the meta-analysis of Wunderlich et al. (1996) on the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia patients revealed equally large effect sizes for family therapy and cognitive therapy for patients. The positive results of the latest Hogarty et al. study (1997a, 1997b), which was included in our meta-analysis, could indicate a particularly good effectiveness of personal therapy, although it should be mentioned that the positive effects of personal therapy on relapse rates were found only among patients who lived with family.

Furthermore, in comparison IV the additional effect of family interventions for schizophrenia patients who received a comprehensive psychosocial treatment was investigated. The relapse rate could not be lowered through an additional family intervention. In the Linszen et al. 1996 study all patients received outstanding medical and psychosocial treatment during the entire study period. It would have therefore been difficult to further improve the outcome through additional family intervention. The psychoeducational sessions offered at the beginning of the intervention under both treatment conditions probably leveled the differences out. For some families, characterized as low-EE in several studies, it might be sufficient to get basic psychoeducation to support the patient adequately. Hogarty et al. showed in their 1991 study the superiority of the combined treatment over an intervention approach focused on the patient alone, whereas in their 1997b study personal therapy with the patient alone brought better long-term results than the combination with a family intervention. As the studies with very positive results for patient interventions are recent studies, it might be imaginable that the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia patients has been improved considerably in recent years. The meta-analysis of Mojtabai et al. (1998) on psychosocial treatments for patients with schizophrenia would support this assumption, showing that more recent studies tended to produce larger effect sizes. Furthermore, psychoeducation has gradually become a basic treatment for all schizophrenia patients and their relatives and part of the usual care, at least in the United States. It might therefore get more and more difficult to produce a significant effect through an additional family treatment.

Limitations

Despite the clearly positive results and new perspectives for the future, some limitations should be kept in mind. First. our meta-analytical calculations were not based on intention to treat (ITT). Because dropout patients could not always be associated with the treatment groups involved in the individual comparisons, ATP analyses were presented. Most of the authors noted that dropout rates in intervention and control groups were not significantly different. Therefore. a systematic error caused by patients dropping out of the study groups was not to be expected. In the Kelly and Scott (1990) study, which had higher dropout rates. especially in the control group (family intervention: 29%, patient intervention: 21%, combination: 30%, usual care: 42%), a small effect size was calculated. In the Hogarty et al. (1997b) study also a particularly high dropout rate was found for the supportive therapy condition (family therapy: 21%, personal therapy: 4%, supportive therapy: 33%) and a small effect size was calculated as well. Thus, an overestimation of the family intervention as a result of the evaluation strategy cannot be assumed. It appeared to be appropriate to use the ATP strategy also considering the content of the meta-analysis, because it should answer the basic question about the additional effect achieved by family interventions. Therefore, the relatives who were randomly assigned to the intervention groups should have gotten the intervention in fact. Other important questions concerning the acceptance among patients, relatives, and professionals or the implementation in routine care should be investigated independently. Nevertheless the possibility that an evaluation according to the ITT strategy would yield findings of less significance cannot be ruled out.

Secondly, unpublished studies remained outside the scope of this meta-analysis. As negative results have a higher tendency to remain unpublished, a bias cannot be excluded, even if there are few indications of unpublished studies concerning the topics treated here.

A third general limitation derives from the fact that the reported findings relate to only schizophrenia patients (1) who have relatives, (2) who are in regular contact with their relatives, and (3) who have relatives willing to become involved on behalf of the schizophrenia patient. At least one-third of all schizophrenia patients (Hogarty 1993; Pitschel-Walz 1997) do not meet these basic prerequisites and, therefore, simply cannot be supported through psychoeducational family interventions. Other treatment strategies must be developed for these patients in theory and practice to actively support them in dealing effectively with their illness. New developments are encouraging, showing that schizophrenia patients can absolutely benefit from psychosocial treatments when they are tailored to the patients’ special needs (Hogarty et al. 1997a; Mojtabai et al. 1998; Schaub 1998). In addition, hopes are raised by the introduction of the new atypical antipsychotic drugs, which have a more favorable side effect profile and may improve the patient’s compliance and contribute to further reduction of the relapse rate (Weiden et al. 1996; Leucht et al. 1999).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis could clearly confirm the hypothesis that psychoeducational family interventions reduce the relapse and rehospitalization rates of schizophrenia patients. In the coming decade the results of this research need to be applied in practical settings to enable as many patients as possible to benefit from these findings. Psychoeducation for patients and their families should become a basic part of a comprehensive psychosocial treatment package that is offered to all schizophrenia patients. Future research should focus on and evaluate the process of integrating family interventions into the clinical routine and examine the long-term effects in more detail.

In this meta-analysis we focused on the relapse rate and the rehospitalization rate as outcome criteria. However, there are further important effects of family interventions that were not investigated here but should be considered when the implementation of family interventions is discussed. In addition to a reduced relapse rate, several studies demonstrated the following:

The overall goal of all scientific efforts finally remains the effective improvement of long-term outcomes for patients with schizophrenia based on antipsychotic drug therapy; psychotherapy; family intervention methods; and new, individualized concepts of psychiatric rehabilitation.

|

|

Table 1. Survey of the Intervention Studies Included

| Study | n1/n2 | Relapse Rates Family Intervention (%) | Usual Care (%) | Effect Size, First Year | Effect Size, Second Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldstein et al. 1978: high dosage | 23/29 | 0 | 14 | 0.26 | |

| Goldstein et al. 1978: low dosage | 23/21 | 22 | 48 | 0.27 | |

| Hogarty et al. 1991 | 21/29 | 19 | 38 | 0.20 | |

| 29 | 62 | 0.33 | |||

| Kelly and Scott 1990 | 75/104 | 35 | 45 | 0.11 | |

| Leff et al. 1985 | 12112 | 9 | 50 | 0.46 | |

| 40 | 78 | 0.38 | |||

| Posner et al. 1992 | 19/20 | 26 | 40 | 0.15 | |

| Randolph et al. 1994 | 21/20 | 38 | 50 | 0.12 | |

| Spencer et al. 1988 | 79/89 | Global outcome: χ2=5.29, df=1, p=0.0214a | 0.18 | ||

| 77/81 | Global outcome: χ2=3.23, df=1, p=0.0723a | 0.14 | |||

| Spiegel and Wissler 1987 | 14/22 | 57 | 50 | −0.07b | |

| Tarrier et al. 1989: long intervention | 25/15 | 12 | 53 | 0.45 | |

| 33 | 60 | 0.26 | |||

| Tarrier et al. 1989: short intervention | 14/15 | 43 | 53 | 0.10 | |

| 57/60 | 60 | 0.03 | |||

| Vaughan et al. 1992 | 17/17 | 41 | 65 | 0.24 | |

| Xiong et al. 1994 | 34/29 | 12 | 36 | 0.28 | |

| 32/28 | 13 | 36 | 0.27 | ||

| Zhang et al. 1994 | 39/39 | 15 | 54 | 0.40 | |

| Mean effect sizes | r̄=0.19 | r̄=0.25 |

| Duration | Type | Study Criteria | Sample Selection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Psychoeducational | Therapeutic | Symptoms | Rehospitalization | Schizophrenia | Mixed Diagnoses | |

| n | 571 | 287 | 648 | 210 | 329 | 529 | 521 | 347 |

| Heterogeneity χ2 | 3.83 | 2.73 | 11.1 | 0.65 | 3.13 | 9.03 | 8.97 | 0.12 |

| df forχ2 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 1 |

| p forχ2 | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.1 | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.1 | >0.5 | >0.5 |

| Mean effect size | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.12 |

| p for mean effect size | <0.005 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.05 |

| z for contrast | 2.36 | 0.61 | 0.09 | 1.75 | ||||

| p for z | <0.05 | >0.5 | >0.5 | 0.08 | ||||

| Relapse Rates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | n1/n2 | Family Intervention + Patient Intervention (%) | Usual Care (%) | Effect Size, First Year | Effect Size, Second Year |

| Buchkremer et al. 1997 | 33/35 | 15 | 22 | 0.10 | |

| 33/34 | 24 | 50 | 0.27 | ||

| Cranach 1981 | 44/42 | 18 | 21 | 0.04 | |

| Hogarty et al. 1991 | 20/29 | 0 | 38 | 0.45 | |

| 25 | 62 | 0.37 | |||

| Kelly and Scott 1990 | 64/104 | 28 | 45 | 0.17 | |

| Pitschel-Walz et al. 1998 | 81/82 | 21 | 38 | 0.18 | |

| 79/74 | 41 | 58 | 0.18 | ||

| Mean effect sizes | r̄=0.17 | r̄=0.23 | |||

| Relapse Rates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | n1/n2 | Family Intervention (%) | Patient Intervention (%) | Effect Size, First Year | Effect Size, Second Year | Effect Size, Third Year |

| Falloon et al. 1982, 1985 | 18/18 | 6 | 44 | 0.45 | ||

| 17 | 83 | 0.67 | ||||

| Hogarty et al. 1991 | 21/20 | 19 | 20 | 0.00 | ||

| 29 | 50 | 0.22 | ||||

| Hogarty et al. 1997, 1b | 24/23 | 33 | 9 | −0.30a | ||

| 22/23 | 41 | 13 | −0.32a | |||

| 19/22 | 53 | 14 | −0.42a | |||

| Hogarty et al. 1997, 2b | 24/24 | 33 | 21 | −0.14a | ||

| 22/18 | 41 | 33 | −0.08a | |||

| 19/16 | 53 | 44 | −0.09a | |||

| Kelly and Scott 1990 | 75/90 | 35 | 35 | 0.00 | ||

| Ro-Trock et al. 1977 | 14/14 | 0 | 43 | 0.52 | ||

| Telles et al. 1995 | n=42 | Survival analysis:χ2=5.91, df=1, p=0.015 | −0.38a | |||

| Mean effect sizes | r̄=−0.01a | r̄=0.12 | r̄=−0.28a | |||

| Relapse Rates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | n1/n2 | Family Intervention (%) | Patient Intervention (%) | Effect Size, First Year | Effect Size, Second Year | Effect Size, Third Year |

| Hogarty et al. 1991 | 20/20 | 0 | 20 | 0.33 | ||

| 25 | 50 | 0.26 | ||||

| Hogarty et al. 1997, 1b | 26/23 | 12 | 9 | −0.05a | ||

| 25/23 | 28 | 13 | −0.18a | |||

| 24/22 | 38 | 14 | −0.27a | |||

| Hogarty et al. 1997, 2b | 26/24 | 12 | 21 | 0.13 | ||

| 25/18 | 28 | 33 | 0.06 | |||

| 24/16 | 38 | 44 | 0.06 | |||

| Linszen et al. 1996 | 37/39 | 16 | 15 | −0.01a | ||

| Mean effect sizes | r̄=0.08 | r̄=0.03 | r̄=–0.12 | |||

|

Table 7. Studies and Effect Sizes (Comparison V: Family Intervention A vs. Family Intervention B)

Abramowitz, I.A., and Coursey, R.D. Impact of an educational support group on family participants who take care of their schizophrenic relatives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(2):232–236, 1989. Crossref, Google Scholar

Barrowclough, C., and Tarrier, N. Psychosocial interventions with families and their effects on the course of schizophrenia: A review. Psychological Medicine, 14:629–642, 1984. Crossref, Google Scholar

Barrowclough, C., and Tarrier, N. Social functioning in schizophrenic patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 25:125–129, 1990. Crossref, Google Scholar

Barrowclough, C.; Tarrier, N.; Watts, S.; Vaughn, C.; Bamrah, J.S.; and Freeman, H.L. Assessing the functional value of relatives’ knowledge about schizophrenia: A preliminary report. British Journal of Psychiatry, 151:1–8, 1987. Crossref, Google Scholar

Bäuml, J. Der Umgang mit schizophrenen Patienten aus der Sicht der Angehörigen. In: Kockott, G., and Möller, H.-J., eds. Sichtweisen der Psychiatrie. München, Germany: W. Zuckschwerdt Verlag, 1993. pp. 42–52. Google Scholar

Bäuml, J.; Kissling, W.; Meurer, C.; Wais, A.; and Lauter, H. Informationszentrierte Angehörigengruppen zur Complianceverbesserung bei schizophrenen Patienten. Psychiatrische Praxis, 18:48–54, 1991. Google Scholar

Bäuml, J.; Pitschel-Walz, G.; and Kissling, W. Psychoedukative Gruppen bei schizophrenen Psychosen für Patienten und Angehörige. In: Stark, A., ed. Verhaltenstherapeutische und psychoedukative Ansätze im Umgang mit schizophren Erkrankten. Tübingen, Germany: dgvt-Verlag, 1996. pp. 217–255. Google Scholar

Bäuml, J.; Pitschel-Walz, G.; and Kissling, W. Psychoedukative Gruppenarbeit bei schizophrenen Psychosen: Spezifische Auswirkungen eines bifokalen Ansatzes auf Krankheitsbewältigung und Rezidivraten im 4-Jahreszeitraum. Ergebnisse der Münchner PIP-Studie. In: Dittmar, V.; Klein, H.E., and Schön, D., eds. Die Behandlung schizophrener Menschen—Integrative Therapiemodelle und ihre Wirksamkeit. Regensburg, Germany: S. Roderer Verlag, 1997. pp. 169–195. Google Scholar

Bellack, A.S., and Mueser, K.T. Psychosocial treatment for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 19(2):317–336, 1993. Crossref, Google Scholar

Bennett Herbert, T., and Cohen, S. Depression and immunity: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 113(3):472–486, 1993. Crossref, Google Scholar

Benton, M.K., and Schroeder, H.E. Social skill training with schizophrenics: A meta-analytic evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58(6):741–747, 1990. Crossref, Google Scholar

Berkowitz, R.; Eberlein-Fries, R.; Kuipers, L.; and Leff, J.P. Educating relatives about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 10(3):418–429, 1984. Crossref, Google Scholar

Birchwood, M.J.; Smith, J.V.; and Cochrane, R. Specific and nonspecific effects of educational intervention for families living with schizophrenia: A comparison of three methods. British Journal of Psychiatry, 160:806–814, 1992. Crossref, Google Scholar

Böker, W. A call for partnership between schizophrenic patients, relatives and professionals. British Journal of Psychiatry, 161(Suppl 18):10–12, 1992. Crossref, Google Scholar

Boonen, M., and Bockhorn, M. Schizophreniebehandlung in der Familie. Psychiatrische Praxis, 19:76–80, 1992. Google Scholar

Brown, G.W.; Birley, J.L.T.; and Wing, J.K. Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders: A replication. British Journal of Psychiatry, 121:214–258, 1972. Crossref, Google Scholar

Brown, G.W.; Carstairs, G.M.; and Topping, G. Post-hospital adjustment of chronic mental patients. The Lancet, 2:685–689, 1958. Crossref, Google Scholar

Brown, G.W.; Monck, E.M.; Carstairs, G.M.; and Wing, J.K. Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic illness. British Journal of Prevention and Social Medicine, 16:55–68, 1962. Google Scholar

Buchkremer, G.; Klingberg, S.; Holle, R.; SchulzeMönking, H.; and Hornung, P. Psychoeducational psychotherapy for schizophrenic patients and their key relatives or care-givers: Results of a 2-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 96:483–491, 1997. Crossref, Google Scholar

Butzlaff, R.L., and Hooley, J.M. Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55:547–552, 1998. Crossref, Google Scholar

Canive, J.M.; Sanz-Fuentenebro, J.; Tuason, V.B.; Vázquez, C.; Schrader, R.M.; Alberdi, J.; and Fuentenebro, F. Psychoeducation in Spain. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 44(7):679–681, 1993. Google Scholar

Cardin, V.A.; McGill. C.W.; and Falloon, I.R.H. An economic analysis: Costs, benefits and effectiveness. In: Falloon, I.R.H., ed. Family Management of Schizophrenia. Baltimore. MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985. pp. 115–123. Google Scholar

Cazzullo, C.L.; Bertrando, P.; Clerici, C.; Bressi, C.; Da Ponte, C.; and Albertini, E. The efficacy of an information group intervention on relatives of schizophrenics. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 35(4):313–3231. 1989. Crossref, Google Scholar

Chalmers, T.C.; Smith. H.; Blackburn, B.; Silverman, B.: Schroeder, B.; Reitman. D.; and Ambroz, A. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2:31–49. 1981. Crossref, Google Scholar

Corrigan, P.W.; Liberman, R.P.; and Engel, J.D. From noncompliance to collaboration in the treatment of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 41(11):1203–1211, 1990. Google Scholar

Cozolino, L.J.; Goldstein, M.J.; Nuechterlein, K.H.; West, L.W.; and Snyder, K. The impact of education about schizophrenia on relatives varying in expressed emotion. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 14(4):675–687, 1988. Crossref, Google Scholar

Cranach, M.V. Psychiatrische Versorgung durch niedergelassene Ärzte und ambulante Dienste. In: Bauer, M., and Rose, H.K., eds. Ambulante Dienste für psychisch Kranke. Köln, Germany: Rheinland-Verlag, 1981. pp. 31–41. Google Scholar

Creer, C., and Wing, J.K. Schizophrenia at Home. Surrey, U.K.: National Schizophrenia Fellowship, 1974. Google Scholar

Dixon, L.B., and Lehman, A.F. Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 21(4):631–643, 1995. Crossref, Google Scholar

Ehlert, U. Psychosocial intervention for the relatives of schizophrenic patients. In: Emmelkamp, P.; Everaed, W.; Kraaimaat, E; and van Son, M., eds. Advances in Theory and Practice in Behaviour Therapy. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger, 1988. S. 251–259. Google Scholar

Esterson, A.; Cooper, D.G.; and Laing, R.D. Results of family-oriented therapy with hospitalized schizophrenics. British Medical Journal, 2:1462–1465, 1965. Crossref, Google Scholar

Fadden, G.; Bebbington, P.; and Kuipers, L. The burden of care: The impact of functional psychiatric illness on the patient’s family. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150:285–292, 1987. Crossref, Google Scholar

Falloon, I.R.H.; Boyd, J.L.; and McGill, CW. Family Care of Schizophrenia. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1984. Google Scholar

Falloon, I.R.H.; Boyd, J.L.; McGill, CW.; Razani, J.; Moss, H.B.; and Gilderman, A.M. Family management in the prevention of exacerbations of schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine, 306:1437–1440, 1982. Crossref, Google Scholar

Falloon, I.R.H.; Boyd, J.L.; McGill, CW.; Williamson, M.; Razani, J.; Moss, H.B.; Gilderman, A.M.; and Simpson, G.M. Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42:887–896, 1985. Crossref, Google Scholar

Falloon, I.R.H.; Hahlweg, K.; and Tarrier, N. Family interventions in the community management of schizophrenia: Methods and results. In: Straube, E.R., and Hahlweg, K., eds. Schizophrenia: Concepts, Vulnerability, and Intervention. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1990. pp. 217–240. Google Scholar

Falloon, I.R.H.; McGill, C.W.; Boyd, J.L.; and Pederson, J. Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia: Social outcome of a two-year longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine, 17:59–66, 1987. Crossref, Google Scholar

Fiedler, P.; Niedermeier, T.; and Mundt, C. Therapeutische Gruppenarbeit mit Angehörigen und Familien schizophrener Patienten—Eine kritische Übersicht. Gruppendynamik, 17(3):255–272, 1986. Google Scholar

Fowler, L. Family psychoeducation: Chronic psychiatrically ill Caribbean patients. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 30(3):27–32, 1992. Google Scholar

Goldstein, MJ. Psychoeducational and family therapy in relapse prevention. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 89(Suppl 382):54–57, 1994. Google Scholar

Goldstein, M.J. Psychoeducation and relapse prevention. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 9(Suppl 5):59–69, 1995. Crossref, Google Scholar

Goldstein, MJ. Psychoeducation and family treatment related to the phase of a psychotic disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11(SuppI 2):77–83, 1996a. Google Scholar

Goldstein, M.J. Psychoeducational family programs in the United States. In: Moscrelly, M.; Rupp, A.; and Sartorius, N.; eds. Handbook of Mental Health Economics, I. Schizophrenia. Chichester, U.K.: J. Wiley and Sons, 1996b. Google Scholar

Goldstein, M.J.; Rodnick, E.H.; Evans, J.R.; May, R.P.A.; and Steinberg, M.R. Drug and family therapy in the aftercare of acute schizophrenics. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35:1169–1177, 1978. Crossref, Google Scholar

Hatfield, A.B. Psychological costs of schizophrenia to the family. Social Work, 23:355–359, 1978. Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E. Metaanalysis of the effects of practice with the chronically mentally ill: A critique and reappraisal of the literature. Social Work, 34:363–373, 1989. Crossref, Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E. Prevention of relapse in chronic schizophrenic patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 54(Suppl):18–23, 1993. Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E.; Anderson, C.M.; Reiss, D.J.; Kornblith, S.J.; Greenwald, D.P.; Javan, C.D.; and Madonia, M.J. Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43:633–642, 1986. Crossref, Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E.; Anderson, C.M.; Reiss, D.J.; Kornblith, S.J.; Greenwald, D.P.; Ulrich, R.F.; and Carter, M. Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48:340–347, 1991. Crossref, Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E.; Greenwald, D.P.; Ulrich, R.F.; Kornblith, S.J.; DiBarry, A.L.; Cooley, S.; Carter, M.; and Flesher, S. Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family: II. Effects on adjustment of patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(11):1514–1524, 1997a. Crossref, Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E.; Kornblith, S.J.; Greenwald, D.P., DiBarry, A.L.; Cooley, S.; Ulrich, R.F.; Carter, M.; and Flesher, S. Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family: I. Description of study and effects on relapse rates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(11):1504–1513, 1997b. Crossref, Google Scholar

Hornung, W.P.; Feldmann, R.; Klingberg, S.; Buchkremer, G.; and Reker, T. Long-term effects of a psychoeducational psychotherapeutic intervention for schizophrenic outpatients and their key-persons-results of a five-year follow-up. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 249(3):162–167, 1999. Crossref, Google Scholar

Hornung, W.P.; Holle, R.; Schulze-Mönking, H.; Klingberg, S.; and Buchkremer, G. Psychoedukativ-psychotherapeutische Behandlung von schizophrenen Patienten und ihren Bezugspersonen. Nervenarzt, 66:828–834, 1995. Google Scholar

Kelly, G.R.; and Scott, J.E. Medication compliance and health education among outpatients with chronic mental disorders. Medical Care, 28(12):1181–1197, 1990. Crossref, Google Scholar

Kissling, W. Schizophrenie: Jedes zweite Rezidiv wäre vermeidbar. Fortschritte der Medizin, 11(Suppl 147):3–5, 1993. Google Scholar

Kissling, W. Compliance, quality assurance and standards for relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 89(SuppI 382):16–24, 1994. Google Scholar

Kissling, W.; Bäuml, J.; and Pitschel-Walz, G. Psychoedukation und Compliance bei der Schizophreniebehandlung. In: Helmchen, H., and Hippius, H., eds. Psychiatrie für die Praxis 23. München, Germany: MMV Medizin Verlag, 1996. pp. 14–23. Google Scholar

Köttgen, C.; Sönnichsen, I.; Mollenhauer, K.; and Jurth, R. Group therapy with the families of schizophrenic patients: Results of the Hamburg Camberwell-family-interview study III. Journal of Family Psychiatry, 5:84–94, 1984. Google Scholar

Kuipers, L. Family burden in schizophrenia: Implications for services. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 28(5):207–210, 1993. Google Scholar

Lam, D.H. Psychosocial family intervention in schizophrenia: A review of empirical studies. Psychological Medicine, 21:423–441, 1991. Crossref, Google Scholar

Leff, J.; Berkowitz, R.; Shavit, N.; Strachan, A.M.; Glass, I.; and Vaughn, C. A trial of family therapy versus a relatives’ group for schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 157:571–577, 1990. Crossref, Google Scholar

Leff, J.; Kuipers, L.; Berkowitz, R.; Eberlein-Vries, R.; and Sturgeon, D. A controlled trial of social intervention in the families of schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 141:121–134, 1982. Crossref, Google Scholar

Leff, J.; Kuipers, L.; Berkowitz, R.; and Sturgeon, D. A controlled trial of social intervention in the families of schizophrenic patients: Two year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 146:594–600, 1985. Crossref, Google Scholar

Lefley, H.P., and Johnson, D.L., eds. Families as Allies in Treatment of the Mentally Ill: New Directions for Mental Health Professionals. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1990. Google Scholar

Leucht, S.; Pitschel-Walz, G.; Abraham, D.; and Kissling, W. Efficacy and extrapyramidal side effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophrenia Research, 35:51–68, 1999. Crossref, Google Scholar

Levene, J.E.; Newman, F.; and Jeffries, J.J. Focal family therapy outcome study: I. Patient and family functioning. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 34(7):641–647, 1989. Crossref, Google Scholar

Levene, J.E.; Newman, F.; and Jeffries, J.J. Focal family therapy: Theory and practice. Family Process, 29(1):73–86, 1990. Crossref, Google Scholar

Lewandowski, L., and Buchkremer, G. Therapeutische Gruppenarbeit mit Angehörigen schizophrener Patienten—Ergebnisse zweijähriger Verlaufsuntersuchungen. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie, 17:2, 1988. Google Scholar

Liberman, R.P.; Cardin, V.A.; McGill, C.W.; Falloon, I.R.H.; and Evans, C.D. Behavioral family management of schizophrenia: Clinical outcome and costs. Psychiatric Annals, 17(9):610–619, 1987. Crossref, Google Scholar

Lindgens, M. Ambulante Familienintervention zahlt sich aus: Kosten durch Prophylaxe minimiert. Fortschritte der Medizin, 11(Suppl 147):7–9, 1993. Google Scholar

Linszen, D.; Dingemans, P.; Van der Does, J.W.; Nugter, A.; Scholte, P.; Lenior, R.; and Goldstein, M.J. Treatment, expressed emotion and relapse in recent onset schizophrenic disorders. Psychological Medicine, 26:333–342, 1996. Crossref, Google Scholar

MacCarthy, B.; Kuipers, L.; Hurry, J.; Harper, R.; and LeSage, A. Counselling the relatives of the long-term adult mentally ill. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154:768–775, 1989. Crossref, Google Scholar

Mari, J.J., and Streiner, D.L. An overview of family interventions and relapse on schizophrenia: Meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Medicine, 24:565–578, 1994. Crossref, Google Scholar

Mari, J.J., and Streiner, D.L. Family intervention for people with schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Iss. 1. Oxford, U.K.: Update Software, 1996. Google Scholar

McCreadie, R.G. The Nithsdale Schizophrenia Surveys: An overview. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 27:40–45, 1992. Crossref, Google Scholar

McCreadie, R.G.; Phillips, K.; Harvey, J.A.; Waldron, G.; Stewart, M.; and Baird, D. The Nithsdale Schizophrenia Surveys: VIII. Do relatives want family intervention—and does it help? British Journal of Psychiatry, 158:110–113, 1991. Crossref, Google Scholar

McFarlane, W.R.; Link, B.; Dushay, R.; Marchal, J.; and Crilly, J. Psychoeducational multiple family groups: Four-year relapse outcome in schizophrenia. Family Process, 34:127–144, 1995a. Crossref, Google Scholar

McFarlane, W.R.; Lukens, E.; Link, B.; Dushay, R.; Deakins, S.A.; Newmark, M.; Dunne, E.J.; Horen, B.; and Toran, J. Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52:679–687, 1995b. Crossref, Google Scholar

McGill, C.; Falloon, I.R.H.; Boyd, J.L.; and Wood-Siverio, C. Family educational intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 34(10):934–938, 1983. Google Scholar

McGill, C., and Lee, E. Family psychoeducational intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 50(3):269–286, 1986. Google Scholar

Mojtabai, R.; Nicholson, R.A.; and Carpenter, B.N. Role of psychosocial treatments in management of schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review of controlled outcome studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(4):569–587, 1998. Crossref, Google Scholar

Mosher, L.R., and Keith, S.J. Psychosocial treatment: Individual, group, family, and community support approaches. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 6(1):10–41, 1980. Crossref, Google Scholar

Pakenham, K.I., and Dadds, M.R. Family care and schizophrenia: The effects of a supportive educational program on relatives’ personal and social adjustment. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 21:580–590, 1987. Crossref, Google Scholar

Penn, D.L., and Mueser, K.T. Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(5):607–617, 1996. Crossref, Google Scholar

Pharoah, EM.; Mari, J.J.; and Streiner, D.L. Family intervention for schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Iss. 4. Oxford, U.K.: Update Software, 1999. Google Scholar

Pitschel-Walz, G. Die Einbeziehung der Angehörigen in die Behandlung schizophrener Patienten und ihr Einfluß auf den Krankheitsverlauf. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang, 1997. Google Scholar

Pitschel-Walz, G.; Kissling, W.; and Bäuml, J. Psychoeducation. In: The Workshop Manager: Evidence Based Medicine in Schizophrenia (CD-ROM), London, U.K.: OCC Multimedia, 1998. Google Scholar

Posner, C.M.; Wilson, K.G.; Kral. M.J.; Lander, S.; and McIlwraith, R.D. Family psychoeducational support groups in schizophrenia. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 62(2):206–218. 1992. Crossref, Google Scholar

Randolph, E.T.; Spencer, E.T.H.; Glynn, S.M.; Paz, G.G.; Leong, G.B.; Shaner, A.L.; Strachan, A.; Van Vort, W.; Escobar, J.L; and Liberman, R.P. Behavioural family management in schizophrenia: Outcome of a clinic-based intervention. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164:501–506, 1994. Crossref, Google Scholar

Rosenthal, R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research, Rev. ed. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 6. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1991. Google Scholar

Rosenthal, R.; and Rubin, D.B. A simple, general purpose display of magnitude of experimental effect. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74:166–169, 1982. Crossref, Google Scholar

Ro-Trock, G.K.; Wellisch, D.K.; and Schoolar, J.C. A family therapy outcome study in an inpatient setting. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 47(3):514–522, 1977. Crossref, Google Scholar

Rund, B.R.; Moe, L.; Sollien, T.; Fjell, A.; Borchgrevink, T.; Hallert, M.; and Næss, P.O. The Psychosis Project: Outcome and cost-effectiveness of a psychoeducational treatment programme for schizophrenic adolescents. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 89:211–218, 1994. Crossref, Google Scholar

Schaub, A. Cognitive-behavioural coping-orientated therapy for schizophrenia: A new treatment model for clinical service and research. In: Perris, C., and McGorry, P., eds. Cognitive Psychotherapy of Psychotic and Personality Disorders: Handbook of Theory and Practice. Chichester, U.K.: John Wiley and Sons, 1998. pp. 91–109. Google Scholar

Schaub, A., and Brenner, H.D. Aktuelle verhaltenstherapeutische Ansätze zur Behandlung schizophren Erkrankter. In: Stark, A., ed. Verhaltenstherapeutische und psychoedukative Ansätze im Umgang mit schizophren Erkrankten. Tübingen, Germany: dgvt-Verlag, 1996. pp. 37–65. Google Scholar

Scherrmann, T., and Seizer, H.-U. Das Tübinger Angehörigenprojekt: Eine Pilotstudie über die Konzeption und Evaluation einer Informationsgruppe für Angehörige schizophrener Patienten. In: Buchkremer, G., and Rath, N., eds. Therapeutische Arbeit mit Angehörigen schizophrener Patienten. Bern, Switzerland: Hans Huber, 1989. pp, 87–91. Google Scholar

Scherrmann, T.E.; Seizer, H.-U.; Rutow, R.; and Vieten, C. Psychoedukative Angehörigengruppe zur Belastungsreduktion und Rückfallprophylaxe in Familien schizophrener Patienten. Psychiatrische Praxis, 19:66–71, 1992. Google Scholar

Schindler, R. Ergebnisse und Erfolge der Gruppenpsychotherapie mit Schizophrenen nach den Methoden der Wiener Klinik. Wiener Zeitschrift für Nervenheilkunde u. deren Grenzgebiete, 15:250–261, 1958. Google Scholar

Schneider, F.; Leitner, D.; and Heimann, H. Psychoedukative Angehörigengruppe bei psychiatrischen Patienten verschiedener Diagnosen. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie, 142(3):247–258, 1991. Google Scholar

Schooler, N.R. The efficacy of antipsychotic drugs and family therapy in the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 6(1)(Suppl):11S–19S, 1986. Crossref, Google Scholar

Schooler, N.R.; Keith, S.J.; Severe, J.B.; and Matthews, S.M. Maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: A review of dose reduction and family treatment strategies. Psychiatric Quarterly, 66(4):279–292, 1995. Crossref, Google Scholar

Schooler, N.R.; Keith, S.J.; Severe, J.B.; Matthews, S.M.; Bellack, A.S.; Glick, I.D.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Kane, J.M.; Ninan, P.T.; Frances, A.; Jacobs, M.; Lieberman, J.A.; Mance, R.; Simpson, G.M.; and Woerner, M.G. Relapse and rehospitalization during maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54:453–463, 1997. Crossref, Google Scholar

Smith, J.V., and Birchwood, M.J. Specific and non-specific effects of educational intervention with families living with a schizophrenic relative. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150:645–652, 1987. Crossref, Google Scholar

Smith, J.V., and Birchwood, M.J. Relatives and patients as partners in the management of schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 156:654–660, 1990. Crossref, Google Scholar

Snyder, K.S., and Liberman, R.P. Family assessment and intervention with schizophrenics at risk for relapse. In: Goldstein, M.J., ed. New Developments in Interventions With Families of Schizophrenics. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1981. pp. 49–60. Google Scholar

Spencer, J.H.; Glick, I.D.; Haas, G.L.; Clarkin, J.F.; Lewis, A.B.; Peyser, J.; DeMane, N.; and Good-Ellis, M. A randomized clinical trial of inpatient family intervention: III. Effects at 6-month and 18-month follow-ups. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145(9):1115–1121, 1988. Crossref, Google Scholar

Spiegel, D., and Wissler, T. Using family consultation as psychiatric aftercare for schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 38(10):1096–1099, 1987. Google Scholar

Strachan, A.M. Family intervention for the rehabilitation of schizophrenia: Toward protection and coping. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 12(4):678–698, 1986. Crossref, Google Scholar

Szmukler, G.I.; Herrman, H.; Colusa, S.; Benson, A.; and Bloch, S. A controlled trial of a counselling intervention for caregivers of relatives with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 31(3–4):149–155, 1996. Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N. Effect of treating the family to reduce relapse in schizophrenia: A review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 82(7):423–424, 1989. Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N., and Barrowclough, C. Family interventions for schizophrenia. Behavior Modification, 14(4):408–440, 1990. Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N.; Barrowclough, C.; Porceddu, K.; and Fitzpatrick, E. The Salford Family Intervention Project: Relapse rates of schizophrenia at five and eight years. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165:829–832, 1994. Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N.; Barrowclough, C.; Vaughn, C.; Bamrah, J.S.; Porceddu, K.; Watts, S.; and Freeman, H. The community management of schizophrenia: A controlled trial of a behavioural intervention with families to reduce relapse. British Journal of Psychiatry, 153:532–542, 1988. Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N.; Barrowclough, C.; Vaughn, C.; Bamrah, J.S.; Porceddu, K.; Watts, S.; and Freeman, H. Community management of schizophrenia: A two-year follow-up of a behavioural intervention with families. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154:625–628, 1989. Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N., Lowson, K.; and Barrowclough, C. Some aspects of family interventions in schizophrenia: II. Financial considerations, British Journal of Psychiatry, 159:481–484, 1991. Crossref, Google Scholar

Telles, C.; Karno, M.; Mintz, J.; Paz, G.; Arias, M.; Tucker, D.; and Lopez, S. Immigrant families coping with schizophrenia-behavioural family intervention v. case management with a low-income Spanish-speaking population. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167:473–479, 1995. Crossref, Google Scholar

Vaughan, K.; Doyle, M.; McConaghy, N.; Blaszczynski, A.; Fox, A.; and Tarrier, N. The relationship between relatives’ expressed emotion and schizophrenic relapse: An Australian replication. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 27:10–15, 1992. Crossref, Google Scholar

Vaughn, C.E. Patterns of emotional response in the families of schizophrenic patients. In: Goldstein, M.J.; Hand, I., and Hahlweg, K., eds. Treatment of Schizophrenia: Family Assessment and Intervention. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1986. pp. 97–106, Google Scholar

Videka-Sherman, L. Metaanalysis of research on social work practice in mental health. Social Work, 33:325–338, 1988. Google Scholar

Waring, E.; Carver, C.; Moran, P.; and Lefcoe, D.H. Family therapy and schizophrenia: Recent developments. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 31(2):154–160, 1986. Crossref, Google Scholar

Weiden, P.; Aquila, R.; and Standard, J. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and long-term outcome in schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 57(Suppl 11):53–60, 1996. Google Scholar

Winefield, H.R., and Harvey, E.J. Determinants of psychological distress in relatives of people with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 19(3):619–625, 1993. Crossref, Google Scholar

Wunderlich, U.; Wiedemann, G.; and Buchkremer, G. Are psychosocial methods of intervention effective in schizophrenic patients? A meta-analysis. Verhaltenstherapie, 6:4–13, 1996. Crossref, Google Scholar

Xiang, M.; Ran, M.; and Li, S. A controlled evaluation of psychoeducational family intervention in a rural Chinese community. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165:544–548, 1994. Crossref, Google Scholar

Xiong, W.; Phillips, R.; Hu, X,; Wang, R.; Dai, Q., Kleinman, J.; and Kleinman, A. Family-based intervention for schizophrenic patients in China. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165:239–247, 1994. Crossref, Google Scholar

Yalom, I.D. Theorie und Praxis der Gruppenpsychotherapie. München, Germany: Verlag J. Pfeiffer, 1984. Google Scholar

Zastowny, T.R.; Lehman, A.F.; Cole, R.E.; and Kane, C. Family management of schizophrenia: A comparison of behavioral and supportive family treatment. Psychiatric Quarterly, 62(2):159–186, 1992. Crossref, Google Scholar

Zhang, M.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; and Philips, M.R. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165(Suppl 24):96–102, 1994. Crossref, Google Scholar