Cognitive Therapy for Psychosis in Schizophrenia: An Effect Size Analysis

Abstract

We conducted a meta-analysis using all available controlled treatment outcome studies of cognitive therapy (CT) for psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Effect sizes were calculated for seven studies involving 340 subjects. The mean effect size for reduction of psychotic symptoms was 0.65. The findings suggest that cognitive therapy is an effective treatment for patients with schizophrenia who have persistent psychotic symptoms. Follow-up analyses in four studies indicated that patients receiving CT continued to make gains over time (ES = 0.93). Further research is needed to determine the replicability of standardized cognitive interventions, to evaluate the clinical significance of cognitive therapy for schizophrenia, and to determine which patients are most likely to benefit from this intervention.

1. Introduction

Despite the effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in treating acute psychosis and in preventing relapse, many patients with schizophrenia continue to experience psychotic symptoms. Although estimates vary, most surveys indicate that between 25 and 50% of patients with schizophrenia experience persistent psychotic symptoms even with optimal pharmacological treatment (Curson et al., 1988; Kane and Marder, 1993; Carpenter and Buchanan, 1994). The search for complimentary interventions to decrease residual psychotic symptoms has led some researchers to cognitive therapy (CT). Cognitive-therapy for psychosis focuses on altering the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors of patients by teaching them skills to challenge and modify beliefs about delusions and hallucinations, to engage in experimental reality testing, and to develop better coping strategies for the management of hallucinations. The goals of these interventions are to decrease the conviction of delusional beliefs, and hence their severity, and to promote more effective coping and reductions in distress.

Although the initial applications of CT for psychosis date back two decades, the vast majority of controlled CT studies have been published within the past 5 years, and conducted almost exclusively in Great Britain (Bouchard et al., 1996; Haddock et al., 1997). The relative lag in controlled research on CT for psychosis can be traced to common assumptions that the cognitive deficits of schizophrenia preclude the use of CT approaches or that such approaches, which assume basic reasoning skills, are inappropriate for clients with psychosis. Nevertheless, the recent acceleration of activity in this research area raises a number of questions. Is CT for psychosis an effective treatment? How can we quantify its effectiveness? How can we combine the results of diverse outcome studies in a meaningful way to draw reliable conclusions about its effects?

In the present paper, we will employ meta-analytic techniques to address these questions. Meta-analysis can be a powerful tool for an outcome researcher in several ways. First, making meaningful comparisons between studies is complicated by a number of methodological issues. Studies vary widely in their use of outcome measures, which include clinician-rated instruments, and self-report measures of cognitive and mood change. Consequently, finding a common metric to compare these ‘apples and oranges’ is an elusive proposition. Meta-analysis provides this common metric in the form of an effect size that can be measured uniformly across studies. Second, studies often differ on several other methodological components, including whether they use control groups, the types of control groups employed (e.g. wait-list, treatment as usual, or psychological placebo), lengths of treatment, and differences in sample selection. Meta-analysis supplies a systematic and quantitative method to explore these differences. Third, interpreting findings from some studies may be complicated by problems of statistical power. Studies comparing two active treatments and reporting null statistical findings actually may be underpowered to detect clinically meaningful treatment effects due to small sample sizes (e.g. <10 subjects per cell). Employing meta-analysis, effect sizes can be combined across studies to increase the power to detect differential treatment or methodological effects. Finally, effect sizes offer advantages over literary reviews that compare findings based on levels of statistical significance because studies with different levels of significance can, in fact, have very similar effect sizes (Glass et al., 1981).

2. Method

2.1. Selection of studies

We selected CT treatment outcome studies for patients with schizophrenia that employed a control group (wait-list control, treatment as usual control, or psychological placebo). In addition, we required that subjects either meet DSM-III, DSM-III-R, or DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1987, 1994) or, for papers published earlier than 1980, subjects would have met them, had they been applied. We included two studies that enrolled patients with delusional disorder (Kuipers et al., 1997; Tarrier et al., 1998) because these patients represented such a small percentage of the total sample in these studies (6%).

For the purposes of this review, we were interested in cognitive treatment studies that focused on decreasing psychotic symptoms and modifying core dysfunctional beliefs. As such, we were not interested in studies of ‘cognitive rehabilitation’, which focus on information-processing deficits, nor were we interested in studies of social skills training that also use behavioral techniques (see Benton and Schroeder, 1990). Behavioral studies that used compensation approaches as their primary intervention (e.g. distraction techniques for hallucinations in (McGuigan, 1966) or monaural occlusion techniques (Green, 1978) were excluded, as were studies that taught illness or medication management skills without trying to modify dysfunctional beliefs (e.g. Eckman et al., 1992). Similarly, behavioral studies in which the primary intervention was the reinforcement or punishment of specific behaviors (e.g. decreasing verbal abuse on a hospital ward; Peniston, 1988) were thought to be sufficiently different to warrant exclusion.

Journal articles were located using five strategies. First, a computer-based CD ROM PsychLIT (American Psychological Association, 1994) search was conducted from the beginning of this database in 1974 to the present. PsychLIT’s database consists of citations from 1300 journals from 50 countries. The search was conducted using the following combination of key terms: schizophrenia, psychosis, cognitive, cognitive-behavioral, treatment, treatment outcome, clinical trial, and comparative study. These terms were used both as free-text form and as major key terms in searching the database. Second, a search using the same key terms was implemented with the MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine, 1994) database from 1966 to the present. MEDLINE is a database derived from more than 3000 medical and biomedical journals. Third, the reference sections of articles located from both CD ROM searches were perused for relevant citations. Fourth, unpublished articles were sought by examining Dissertation Abstracts from 1980 to the present. Fifth, articles ‘in press’ were included if we had knowledge of them due to their presentation at national conferences prior to January 2000.

A total of 25 articles were initially identified for possible analysis, but 17 of these were excluded because they did not use a control condition; many of these were pilot studies using a single case or multiple baseline designs. Among the remaining eight studies, one more was excluded because its intervention did not focus on changing psychotic symptoms (Jackson et al., 1998). We decided to include one study that used acute episode inpatients (Drury et al., 1996), because it employed CT techniques that were very similar to those used in outpatient studies, and combined them with medication over a comparable time period. The final pool of studies for this meta-analysis consisted of seven controlled reports.

2.2. Meta-analysis procedure

For the purposes of this paper, we were interested primarily in assessing changes in psychotic symptoms. In order to reduce the potential source of measurement error from heterogeneous dependent measures, we decided to derive effect sizes from validated clinician-rated scales. These scales included the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Lukoff et al., 1986), Psychiatric Assessment Scale (PAS; Krawieka et al., 1997), the Comprehensive Psychiatric Rating Scale-Schizophrenia Change (CPRS; Asberg et al., 1978), and the Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Scale (MADS; (Buchanan et al., 1993).

Effect sizes were derived using Smith and Glass’s delta procedures (Glass et al., 1981). Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting the mean of the posttreatment control group from the posttreatment experimental group(s), and then dividing by the standard deviation of the control group at posttreatment:

A number of different methods were used if the means and standard deviations of a comparison group were not reported. If the t statistic was reported, ES was calculated from:  ). If the results were reported by F score, t was calculated by:

). If the results were reported by F score, t was calculated by:  ; then, the above formula for t was applied. If only the significance level was reported, procedures based on Glass et al. (1981) (pp. 128–129) were utilized to determine t, and then t was entered into the above formula. If proportions of the number of individuals ‘improved’ or ‘not improved’ were reported in the study, effect sizes were computed from a table reported by Glass et al. (1981) (p. 139). These proportions were rounded to the nearest 5% for purposes of comparison.

; then, the above formula for t was applied. If only the significance level was reported, procedures based on Glass et al. (1981) (pp. 128–129) were utilized to determine t, and then t was entered into the above formula. If proportions of the number of individuals ‘improved’ or ‘not improved’ were reported in the study, effect sizes were computed from a table reported by Glass et al. (1981) (p. 139). These proportions were rounded to the nearest 5% for purposes of comparison.

Dependent measures mentioned in the Method section of articles but not presented in the Results section were assumed to be non-significant. Nonsignificant results were assumed to be P = 0.50 unless otherwise specified. Both of these decisions were conservative and were likely to reduce the overall effect size; however, this approach was chosen so that greater confidence could be placed in the results. Effect sizes were computed for each dependent variable at posttreatment and, when available, at follow-up. The effect sizes of all studies were tested for heterogeneity using the Rosenthal (1991) Chi-square test for heterogeneity.

Follow-up effect sizes were drawn from the same outcome measures as posttreatment effect sizes. We used a minimum follow-up period of 6 months, and four studies met these criteria.

3. Results

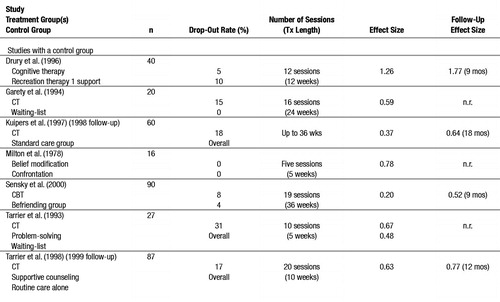

Effect sizes for changes in psychotic symptoms from pretreatment to posttreatment are presented in Table 1, along with the type of control group employed, sample size, length of treatment, and drop-out rates for each experimental and control group. Follow-up effect sizes are presented for the four studies that assessed it. All studies satisfied Rosenthal’s Chi-square test for heterogeneity.

3.1. Sample characteristics

We were initially interested in examining whether several variables related to sample characteristics (e.g. sex, duration of illness) had a systematic effect on the magnitude of the effect size. Nearly all studies (six of seven) assessed the male/female ratio in their samples; 70% of subjects were men, and 30% were women. Simple regression analyses revealed no significant relationship between sex distribution across studies and the effectiveness of the active treatment (P = 0.31; df = 1, 5; P = 0.60). In other words, studies with a high proportion of men did not appear to have significantly higher or lower effect sizes. This conclusion is tentative, however, given that study results were not broken down by sex, precluding a more definitive evaluation.

The duration of illness was determinable in six of seven studies; the mean duration of the disorder was 14.0 years (S.D. = 3.2; range = 11.0–18.2), suggesting a chronically ill sample. In only one study (Drury et al., 1996) were patients less chronic. In this study, 66% were experiencing their first or second episode of psychosis, and 70% of the participants were within the first 5 years of presentation. The total number of past hospital admissions was assessed in six of seven studies with a mean of 3.4 (S.D. = 0.8; range = 2.5–4.8).

The medication status of patients in these studies was nearly uniform, with 100% taking psychotropic medication in six studies and 95% of patients taking medication in one study. In five of the studies, subjects were outpatients, and in two, they were inpatients.

Diagnostically, patients in these studies were a representative sample of community patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Eighty-nine per cent of the sample met criteria for schizophrenia, 7% had schizoaffective disorder, and 4% had delusional disorder. Patients with comorbid primary drug and alcohol abuse were excluded from these studies, as were patients with organic brain pathology. In most studies, patients were required to have at least one positive symptom that was distressing to them.

3.2. Treatment outcome and characteristics

The mean effect size for change in psychotic symptoms from pre- to posttreatment was 0.65 (95% CI = 0.56–0.71). This effect size is categorized as a ‘large effect size’ according to estimates designated by Glass et al. (1981). This finding is consistent with the ‘qualitative’ clinical findings reported in these studies. All seven studies reported significant decreases in positive symptoms at posttreatment, and five of seven reported significant decreases for CT relative to the control condition at posttreatment. The overall drop-out rate in these studies was 12.4%. The two studies with the lowest levels of attrition (Milton et al., 1978; Drury et al., 1996) used inpatients. Participation refusal rates were not uniformly assessed across studies, even though these statistics may be more meaningful than attrition rates in studies of schizophrenia.

The number of sessions of CT treatment and treatment duration are also included in Table 1. The mean number of sessions of CT treatment was 13.6 (S.D. = 5.7) with a range of five to 20 sessions. Simple regression analyses revealed no significant relationship between number of sessions of CT treatment and change in psychotic symptoms (R = 0.28; df = 1,4; p = 0.64). In three studies, the treatment intensity varied across subjects (Garety et al., 1994; Kuipers et al., 1997; Sensky et al., 2000) and, as such, these studies were excluded from this analysis.

CT treatment format was fairly consistent across studies; six of seven studies employed an individual therapy format, and one study (Drury et al. 1996) used combined individual and group therapy. The content of the CT interventions was also fairly similar across studies. All studies focused on modifying beliefs about delusions and hallucinations in order to decrease the impact that these phenomena had on patients’ lives. Therapists used a collaborative process in which they worked closely with a patient to understand the delusions or hallucinations from his/her perspective. They often employed specific strategies such as identifying cognitive errors, Socratic questioning, acting on beliefs to test their validity, and seeking the assistance of others in collecting disconfirming evidence for their beliefs. Study therapists also frequently used a hierarchical approach to change delusions by starting with the least strongly held beliefs and then progressing to more firmly held beliefs. The two studies by Tarrier and his colleagues used an intervention called Coping Strategy Enhancement in which the aim is to determine which environmental factors maintain psychotic symptoms as well as to teach better coping strategies; hypothesis testing skills and relapse prevention skills were also taught. In addition to modifying delusional beliefs, the Kuipers et al. (1997) and Garety et al. (1994) studies focused on changing dysfunctional schemas (e.g. that the patient was a bad and worthless person).

Treatment was conducted by doctoral-level (‘clinical doctorate’ in the UK) psychologists in four of the studies and psychiatric nurses in one study (Sensky et al., 2000), and the level of training was unclear in the two remaining studies (Milton et al., 1978; Drury et al., 1996). Although assessment raters were not the providers of treatment, they were not blind to treatment allocation. Use of independent raters was not mentioned in either the Drury et al. (1996) or the Milton et al. (1978) studies and therefore was assumed not to have been employed.

3.3. Long-term treatment outcome

Examination of the long-term efficacy of controlled research studies may be restricted by the difficulties in maintaining patients in control conditions over time. In the present meta-analysis, four studies assessed outcome past 6 months posttreatment. Interestingly, in all four studies, patients continued to improve significantly over the follow-up periods, and their combined mean effect size at follow-up was 0.93. In the Drury et al. (1996) study, only 5% of CT subjects showed moderate or severe residual symptoms of psychosis at follow-up compared to 56% of patients in the control group. Similarly, in the Kuipers et al. (1997) study, patients in the CT group continued to make a modest improvement in BPRS scores, while control patients got worse. In the Sensky et al. (2000) study, CBT and Befriending Control subjects were not different at posttreatment but were significantly different at 9 month follow-up. Patients in the Tarrier et al. (1999) trial maintained their posttreatment gains during the 12 month follow-up.

4. Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis of the effects of CT for psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. The effect size of 0.65 across seven controlled studies is large, and indicates that cognitive interventions represent a promising strategy for decreasing the severity of persistent delusions and hallucinations, or improving patients’ abilities to manage those distressing symptoms. Considering the high proportion of patients with schizophrenia who experience continued psychotic symptoms despite optimal pharmacological treatment, CT may represent an important, new intervention in the management of this serious disorder. In addition, the effects of CT over time appear to be quite robust (ES = 0.93).

Although the results of this meta-analysis demonstrate the strong effects of CT for schizophrenia, there are limitations to the studies conducted thus far, and many questions remain. Despite promising early research on CT for psychosis (Milton et al., 1978), research on this treatment has been conducted almost exclusively in Great Britain by the developers of the cognitive interventions. There is a need to evaluate the replicability of CT for schizophrenia in additional treatment settings and to determine the generalizability of the intervention when performed by clinicians not working directly under the treatment innovators. In addition, although some studies successfully used independent evaluators, (e.g. Kuipers et al., 1997), others used evaluators who were blind to group allocation but not to the timing of the assessments (e.g. Tarrier et al., 1993, 1999). Future research would benefit from more consistent use of ‘blind’ evaluators.

The patients included in the studies reviewed were mostly males who were treated in outpatient settings. Although there are no a priori reasons for hypothesizing that CT would be less effective for women, or when conducted in inpatient settings, studies need to evaluate the effects of CT in more heterogeneous patient populations. Another methodological issue concerns the strength of the control group used in deriving effect sizes. The relative strength of a control group and its effect size when compared to the experimental treatment are inversely proportional (Gould et al., 1995). In the present meta-analysis, two studies employed control groups that were matched to the CT group in level of treatment (Tarrier et al., 1998; Sensky et al., 2000). Thus, the effect sizes of the CT intervention in these studies might be an underestimate of the ‘true’ effect size of CT when compared to ‘treatment as usual’.

Another important question raised by research on CT for psychosis is the clinical and functional significance of treatment gains. There is a broad consensus that poor functioning in the areas of social relationships, work, and self-care in schizophrenia is more strongly related to the severity of negative symptoms and cognitive impairment than psychotic symptoms (Liddle, 1987; Bellack et al., 1990; Glynn et al., 1992; Brekke et al., 1994). However, persistent psychotic symptoms are associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression (Tarrier, 1987; Mueser et al., 1991) and with increased vulnerability to relapse and rehospitalization. Only two studies of CT evaluated effects on relapse and rehospitalization, with one study reporting no relapses in the CT and supportive counselling groups (Tarrier et al., 1998), and the other failing to find significantly lower relapse and rehospitalization rates (Kuipers et al., 1997). The Kuipers et al. (1998) study did, however, find that the CT group experienced fewer (but non-significant) in-patient care days in hospital relative to the control condition. Even a modest effect of CT on rehospitalization rates would be of considerable clinical and economic importance. Aside from its effects on relapse, CT may benefit patients by reducing distress associated with psychotic symptoms. More work is needed to evaluate the effects of CT on the course of the illness and patient distress in order to determine its proper place in the comprehensive treatment of schizophrenia.

Conventional wisdom has held that patients with schizophrenia are not amenable to CT because of psychosis, cognitive impairment, and the lack of insight that often accompanies it. Clearly, this is not the case. It remains to be determined which patients are most able to benefit from CT. Garety et al. (1997) reported that cognitive flexibility, which was correlated with insight, predicted benefit from CT, while a brief test of cognitive impairment did not. Further research is needed to evaluate this in larger samples of patients and to determine whether reliable predictors of treatment response can be identified.

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that CT has a significant effect on improving symptoms in patients with schizophrenia who experience psychotic symptoms. Although research evaluating the effects of CT with this population is limited, the studies reviewed here included strong experimental designs, well-articulated treatment interventions (which were in most cases standardized in the form of a treatment manual), and comprehensive assessment batteries. These encouraging findings warrant further research on CT for schizophrenia designed to replicate findings by other investigators, to evaluate which patients are most likely to benefit, and to better understand the effects of CT on other areas of functioning presumably related to severity of psychotic symptoms, including relapses and rehospitalizations, distress, and quality of life.

|

Table 1. Mean Effect Sizes for Measures of Change in Psychotic Symptoms for Cognitive Therapy Interventions at Posttreatmenta

American Psychiatric Association, 1980. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. third ed., American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association, 1987. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III-R. revised ed., American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association, 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. fourth ed., American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.Google Scholar

American Psychological Association, 1994. PsychLIT Database (CD-ROM). American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.Google Scholar

Asberg, M., Montgomery, S.A., Perris, C., Shalling, D., Sedvall, G., 1978. A comprehensive psychopathological rating scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 271 (Suppl.), 5–27.Google Scholar

Bellack, A.S., Morrison, R.L., Wixted, J.T., Mueser, K.T., 1990. An analysis of social competence in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 156, 809–818.Crossref, Google Scholar

Benton, M.K., Schroeder, H.E., 1990. Social skills training with schizophrenics: A meta-analytic evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 58, 741–753.Crossref, Google Scholar

Bouchard, S., Vallieres, A., Roy, M., Maziade, M., 1996. Cognitive restructuring in the treatment of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia: A critical analysis. Behavior Therapy 27, 257–277.Crossref, Google Scholar

Brekke, J.S., Debonis, J.S., Graham, J.W., 1994. A latent structure analysis of the positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry 235, 252–259.Crossref, Google Scholar

Buchanan, A., Reed, A., Wessley, S., Garety, P., Taylor, P., Grubin, D., Dunn, G., 1993. Acting on delusions (2): The phenomenological correlates of acting on delusions. British Journal of Psychiatry 163, 77–81.Crossref, Google Scholar

Carpenter Jr., W.T., Buchanan, R.W., 1994. Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 330, 681–690.Crossref, Google Scholar

Curson, D.A., Patel, M., Liddle, P.F., Barnes, T.R.E., 1988. Psychiatric morbidity of a long-stay hospital population with chronic schizophrenia and implications for future community care. British Medical Journal 297, 819–822.Crossref, Google Scholar

Drury, V., Birchwood, M., Cochrane, R., MacMillan, F., 1996. Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: A controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 169, 593–601.Crossref, Google Scholar

Eckman, T.A., Wirshing, W.C., Marder, S.R., Liberman, R.P., Johnston-Cronk, K., Zimmermann, K., Mintz, J., 1992. Technique for training schizophrenic patients in illness self-management: A controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 149, 1549–1555.Crossref, Google Scholar

Garety, P.A., Kuipers, L., Fowler, F., Chamberlain, F., Dunn, G., 1994. Cognitive behavioural therapy for drug-resistant psychosis. British Journal of Medical Psychology 67, 259–271.Crossref, Google Scholar

Garety, P., Fowler, D., Kuipers, E., Freeman, D., Dunn, G., Bebbington, P., Hadley, C., Jones, S., 1997. London–East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychosis II: Predictors of outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry 171, 420–426.Crossref, Google Scholar

Glass, G.V., McGaw, G., Smith, M.L., 1981. Meta-analysis in Social Research. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA.Google Scholar

Glynn, S.M., Randolph, E.M., Eth, S., Paz, G.G., Leong, G.B., Shaner, A.L., Van Vort, W., 1992. Schizophrenia symptoms, work adjustment and behavioral family therapy. Rehabilitation Psychology 37, 323–338.Crossref, Google Scholar

Gould, R.A., Otto, M.W., Pollack, M.H., 1995. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. Clinical Psychology Review 15, 819–844.Crossref, Google Scholar

Green, P., 1978. Defective interhemispheric transfer in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 87, 472–480.Crossref, Google Scholar

Haddock, G., Tarrier, N., Spaulding, W., Yusupoff, L., Kinney, C., McCarthy, E., 1997. Individual cognitive-behavior therapy in the treatment of hallucinations and delusions: A review. Clinical Psychology Review 18, 821–838.Crossref, Google Scholar

Jackson, H., McGorry, P., Edwards, J., Hulbert, C., Henry, L., Francey, S., Maude, D., Cocks, J., Power, P., Harrigan, S., Dudgeon, P., 1998. Cognitively-oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis (COPE). British Journal of Psychiatry 173, 93–100.Google Scholar

Kane, J.M., Marder, S.R., 1993. Psychopharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19, 287–302.Crossref, Google Scholar

Krawieka, M., Goldberg, D., Vaughan, M., 1997. A standardised psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 55, 299–308.Crossref, Google Scholar

Kuipers, E., Garety, P., Fowler, D., Dunn, G., Bebbington, P., Freeman, D., Hadley, C., 1997. London–East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 171, 319–327.Crossref, Google Scholar

Kuipers, E., Fowler, D., Garety, P., Chisholm, D., Freeman, D., Dunn, G., Bebbington, P., Hadley, C., 1998. London–East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychosis III: Follow-up and economic evaluation at 18 months. British Journal of Psychiatry 173, 61–68.Crossref, Google Scholar

Liddle, P.F., 1987. The symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: A reexamination of the positive–negative dichotomy. British Journal of Psychiatry 151, 145–151.Crossref, Google Scholar

Lukoff, D., Nuechterlein, K.H., Ventura, J., 1986. Manual for the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Schizophrenia Bulletin 12, 594–602.Google Scholar

McGuigan, F.J., 1966. Covert oral behaviour and auditory hallucinations. Psychophysiology 3, 73–80.Crossref, Google Scholar

Milton, F., Patwa, V.K., Hafner, R.J., 1978. Confrontation vs. belief modification in persistently deluded patients. British Journal of Medical Psychology 51, 127–130.Crossref, Google Scholar

Mueser, K.T., Douglas, M.S., Bellack, A.S., Morrison, R.L., 1991. Assessment of enduring deficit and negative symptom subtypes in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17, 565–582.Crossref, Google Scholar

National Library of Medicine, 1994. MEDLINE Database. BRS Information Technologies, McLean, VA.Google Scholar

Peniston, E.G., 1988. Evaluation of long-term therapeutic efficacy of behavior modification program with chronic male psychiatric patients. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 19, 95–101.Crossref, Google Scholar

Rosenthal, R., 1991. Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research. revised ed. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.Google Scholar

Sensky, T., Turkington, D., Kingdon, D., Scott, J., Scott, J., Siddle, R.O, Carroll, M., Barnes, T.R.E., 2000. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for persistent symptoms in schizophrenia resistant to medication. Archives of General Psychiatry 57, 165–172.Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N., 1987. An investigation of residual psychotic symptoms in discharged schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 26, 141–143.Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N., Beckett, R., Harwood, S., Baker, A., Yusupoff, L., Ugarteburu, I., 1993. A trial of two cognitive-behavioural methods of treating drug-resistant residual psychotic symptoms in schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 162, 524–532.Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, N., Wittkowski, A., Kinney, C., McCarthy, E., Morris, J., Humphreys, L., 1999. Durability of the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of chronic schizophrenia: 12-month follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 174, 500–504.Crossref, Google Scholar

Tarrier, R.N., Yusupoff, L., Kinney, C., McCarthy, E., Gledhill, A., Haddock, G., Morris, J., 1998. A randomized controlled trial of intensive cognitive behaviour therapy for patients with chronic schizophrenia. British Medical Journal 317, 303–307.Crossref, Google Scholar