Patient Management Exercise for Psychosomatic Medicine

Abstract

This exercise is designed to test your comprehension of material presented in this issue of FOCUS as well as your ability to evaluate, diagnose, and manage clinical problems. Answer the questions below, to the best of your ability, making your decisions as you would with a real-life patient.

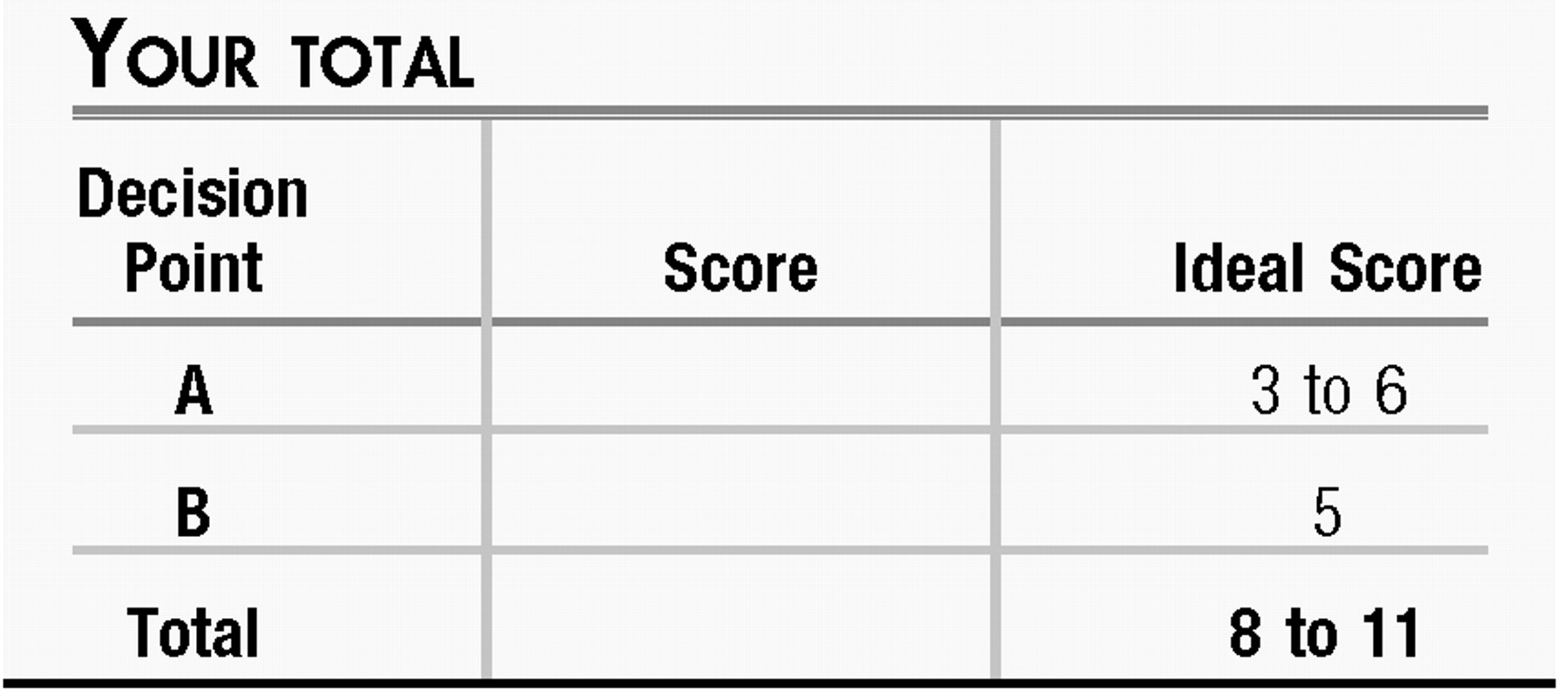

Questions are presented at “decision points” that follow a section that gives information about the case. One or more choices may be correct for each question; make your choices on the basis of your clinical knowledge and the history provided. Read all of the options for each question before making any selections. You are given points on a graded scale for the best possible answer(s), and points are deducted for answers that would result in a poor outcome or delay your arriving at the right answer. Answers that have little or no impact receive zero points. On questions that focus on differential diagnoses, bonus points are awarded if you select the most likely diagnosis as your first choice. At the end of the exercise you will add up your points to obtain a total score.

The management of psychiatric conditions in patients hospitalized for medical or surgical treatment poses special concerns. In addition to the classic issues posed by managing the biological and psychosocial aspects of a psychiatric condition in a patient with multiple other problems, the current system of care of inpatient hospitalization can unexpectedly add complicating factors.

CASE VIGNETTE

Jim is a 24-year-old man who was admitted to the hospital 4 days ago after sustaining numerous orthopedic injuries as the seat-belted front-seat passenger in a motor vehicle accident; you are asked to consult on his case during his hospitalization because he seems “depressed” and “uncooperative.”

Jim is a law student at a nearby university. On the evening of the accident, he and the other occupants in the car had been out to dinner to celebrate the end of the semester. Their car had been hit when another car crossed the median divider and collided head-on; airbags had deployed. Immediately after the collision Jim was awake at the scene, but transiently confused. He endorsed having had only “two beers” that evening, and blood alcohol levels upon arrival in the emergency room were consistent with that history. Paramedics had intubated him in the field to protect his airway, and from the emergency room he had been taken promptly to the operating room for debridement and repair of a compound left femoral fracture. He had been sedate for the first 24 hours postoperatively, but nursing notes and physician progress notes from postoperative days 2 and 3 describe periods of “restlessness” and “irritability” with shouting at staff to “leave me alone” when dressings needed to be changed, and other periods of being tearful and withdrawn. Postoperative pain had been managed initially with scheduled doses of morphine sulfate, but now that the patient could take medications and liquids orally, moderate doses of hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin) were being used with meperidine (Demerol) for breakthrough pain.

Consideration Point A:

Before you interview the patient, which item ranks most highly in your thinking as to potential etiology of the behavioral disturbances that prompt the consult?

| A1._____ | Alcohol withdrawal |

| A2._____ | Side effects from the narcotic analgesic agents |

| A3._____ | Urinary tract infection |

| A4._____ | Fat embolus from the femoral fracture |

| A5._____ | Depression or some other mood disorder, as suggested by the primary team |

VIGNETTE CONTINUES

The patient guardedly allowed you to assess his situation. After promising him that you would not write anything in his medical records of a sensitive nature, you learned that the patient had been experiencing a recurrence of major depression in recent months; his first episode had been in college, and at that time he had seen a therapist for a few months and the episode resolved. His mother has had recurrent depression, successfully treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Nine months ago when this episode began, he sought out a private psychiatrist and began paroxetine at 20 mg nightly; this was increased to 30 mg/day for the past 6 months. With this treatment, his symptoms of depression had been in remission before the motor vehicle accident.

He did not acknowledge that he was taking the antidepressant when he entered the hospital because he didn't want his friends to know that he was in treatment for depression. The paramedics and doctors in the ER had asked about his medications only in front of all his friends, with blatant disregard for what he viewed as private, confidential information. He shared with you that he had experienced a “discontinuation syndrome” reaction about 6 months ago, with similar feelings of restlessness, irritability, and emotional lability; on that occasion he had gone away for a 3-day weekend and neglected to bring along his medication.

Your bedside examination revealed that he had some minor attentional difficulties (easily distracted by alarm sounds from other patients' rooms), an affect that was constricted, and a mood that was “depressed and anxious” and that he was oriented to person and place but was off by 1 day for the date. He was somewhat slowed psychomotorically. His thought process was linear and well organized, and his thought content was notable for his despair at how an evening of fairly tame celebration had led to his orthopedic injuries and the risk of having his psychiatric history disclosed. His insight and judgment appeared to be acceptable.

Consideration Point B:

What recommendation do you offer the team?

| B1._____ | Resume paroxetine, starting at 20 mg every evening. |

| B2._____ | Use lorazepam 0.5 mg every 6 hours as needed for restlessness. |

| B3._____ | Give a single dose of fluoxetine 20 mg. |

| B4._____ | Give haloperidol 0.5 mg orally every 8 hours as needed for agitation/irritability. |

ANSWERS: SCORING, RELATIVE WEIGHTS, AND COMMENTS

Points awarded for correct and incorrect answers are scaled from best (3) to unhelpful but not harmful (0) to dangerous (−3).

Consideration Point A:

| A1._____ | −1 Alcohol withdrawal. A 20-something man who has been out celebrating with friends may fit an actuarial profile of being at risk for misusing alcohol, and withdrawal symptoms emerging after a few days of “enforced abstinence” are a common occurrence when patients are taking nothing by mouth. This patient's history is of only two beers on the night of the motor vehicle accident, and blood alcohol level data were consistent with that being the truth, going against this possibility. If liver function test results were elevated, the possibility of longer-standing alcoholism might be important to consider, but with normal results, this item can be de-prioritized. |

| A2._____ | +2 Narcotic analgesic side effects. Reactions of lability, disinhibition, and irritability may be idiosyncratically associated with the CNS effects of narcotic analgesics, along with the more classic effects of mental slowing or sedation. Assessing any temporal pattern relating times of doses with times of behavioral issues could help clarify the relevance of these agents to the patient's behavioral and emotional symptoms. |

| A3._____ | −2 Urinary tract infection. Although urinary tract infections are a common reason for delirium in older adults, they are not frequent in generally healthy men in this age group, and seldom are associated with CNS effects in the absence of urinary system findings of frequency, urgency, pain, and cloudy urine. Urine dip was performed on admission along with a urine toxicology screen, and both showed negative findings. |

| A4._____ | +1 Fat embolus. Fat emboli from fractures of long bones fortunately are not common but do have the potential to be lethal; confusion can be a presenting symptom. Jim's confusion was reported to be transient rather than persistent or progressive. If vital signs and pulse oximetry results are unremarkable, then the likelihood of this phenomenon is lower. |

| A5._____ | +3 Mood disorder. Inpatient teams may raise the question of depression in a patient who presents as lacking the motivation to enthusiastically embrace their directions, whether for vigorous incentive spirometry or postoperative physical rehabilitation. However, other features of this patient's situation—being tearful and withdrawn, showing irritability, and wishing to be left alone—could also point to the possibility of a preexisting mood disturbance as well as adjustment disorder or acute stress disorder. Alas, a full and truthful response may not be forthcoming when the question “are you depressed?” is asked by an imposing figure towering over a patient in bed, especially when posed at 5:30 a.m. during rounds with an entourage of staff crowding around the bed; tactful assessment during a private interview is more likely to be revealing. |

Consideration Point B:

| B1._____ | +3 Resume paroxetine. By history, the patient has achieved remission with paroxetine at 30 mg/day and would still be taking it had he not been admitted after the motor vehicle accident. Resuming an SSRI is a common strategy for relieving discontinuation syndrome and tends to be effective with modest rapidity. Given that he has missed doses for several days, a conservative approach would be to restart this agent at 20 mg/day with a plan to increase the dose to his prior dose of 30 mg/day in a week. |

| B2._____ | +2 Address symptoms with lorazepam. Benzodiazepines can ease some of the symptoms of discontinuation syndrome (1), and the use of low-dose lorazepam can be justified as an intervention for restlessness and agitation while waiting for resumption of his antidepressant to remedy the underlying pathophysiology of the discontinuation syndrome. (This can also be a useful tactic when it is not possible for a patient to resume antidepressant treatment promptly, e.g., because of continued nothing by mouth status.) |

| B3._____ | −1 Fluoxetine. Some have suggested that the pharmacokinetic properties of fluoxetine can be advantageously used to manage antidepressant discontinuation syndrome (2, 3), particularly when one is tapering a medication that is being discontinued. Because the goal you and the patient share is for him to resume taking a therapeutic dose of the agent that had led to his remission, rather than stopping antidepressant treatment or transitioning to something else, this is not a preferred strategy in this situation. |

| B4._____ | −3 Haloperidol. Neuroleptic agents have a long history of off-label use in helping to manage the agitation and confusion associated with delirium. The patient's mental status examination showed fairly good cognitive function, so the possible benefits do not clearly outweigh the potential risks. |

1 Shelton RC: Steps following attainment of remission: discontinuation of antidepressant therapy. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 3: 168– 174Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Benazzi F: Fluoxetine for the treatment of SSRI discontinuation syndrome. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008; 11: 725– 726Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Haddad PM: Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes. Drug Saf 2001; 24: 183– 197Crossref, Google Scholar