Ask the Expert: Psychosomatic Medicine/Delirium

I have been asked to consult on a patient who suffers from delirium. What are the pertinent risk factors and are there any good treatment algorithms?

Delirium is a challenging neuropsychiatric problem affecting medically ill patients. It is also the most common psychiatric syndrome found in the general hospital setting. Its prevalence surpasses that of the most commonly known and identified psychiatric syndromes and varies depending on the medical setting (1). By definition, delirium is an acute or subacute organic mental syndrome characterized by disturbance of consciousness, global cognitive impairment, disorientation, the development of perceptual disturbance, attention deficits, disordered sleep-wake cycle, fluctuation in presentation (e.g., waxing and waning), and changes in psychomotor activity (depending on the type of delirium) (1).

Seldom are we able to identify a single clear cause for the development of delirium in any one patient. Therefore, the syndrome of delirium is better understood as having a multifactorial etiology. These multiple etiological entities may give rise to transient disruption of normal neuronal activity, which in turn cause the various manifestations of delirium. Details of the pathogenesis of delirium have been discussed extensively elsewhere (2).

Of the many risk factors identified as causative of delirium (1), the following are the most common:

Age. Studies have suggested that age is an independent predictor of a transition to delirium (3, 4). The increased incidence of delirium in older patients may be associated with a decrease in the volume of acetylcholine-producing cells occurring during the normal aging process (5). Data suggest that the probability of transitioning to delirium increases dramatically (by 2%) for each year of life after age 65 (6). Others have demonstrated that older patients have a higher incidence of development of postoperative delirium, even after relatively simple outpatient surgery (7).

Baseline cognitive level of functioning. Studies in both the acute medical ward and surgical units suggest that the presence of baseline cognitive decline or dementia increases the occurrence of delirium (3, 4, 8–10). A study of elderly subjects undergoing joint replacement demonstrated that the presence of dementia significantly increased the occurrence of delirium (31.8% in the population without dementia versus 100% of subjects with dementia) (11). Yet, even in individuals without dementia, the presence of subtle preoperative attention deficits was closely associated with a four to five times increase in the development of postoperative delirium (12).

Gender. Studies suggest that most patients who develop delirium are male (63% male versus 37% female) (3, 13).

Sensory impairment. Of the various forms of sensory impairment, only visual impairment has been shown to contribute to delirium (4). In fact, studies have shown that visual impairment can increase the risk of delirium 3.5-fold (14).

Exogenous substances. Many substances have been associated with a greater deliriogenic potential, including benzodiazepines (3, 6, 15, 16), corticosteroids (16, 17), and opioids (16–18). For example, studies have shown that the probability of transitioning to delirium increased with the dose of lorazepam administered in the previous 24 hours. This incremental risk was large at low doses and plateaued at around 20 mg/day (6, 19). Yet the most direct evidence indicates that a substance's anticholinergic potential is related to delirium (20, 21). In fact, some have demonstrated that the threshold for delirium occurs when the anticholinergic serum level reaches 0.80 ng/ml (21).

Endogenous anticholinergic substances. Studies have demonstrated that detectable serum anticholinergic activity (SAA) have been found in delirious patients who were not exposed to pharmacologic agents with known anticholinergic activity. These findings suggest that endogenous anticholinergic substances may exist during acute illness and may be implicated in the etiology of delirium (22–24).

Immobility and physical restraints. The use of restraints, including endotracheal tubes (ventilator), soft and leather restraints, intravenous lines, bladder catheters, and intermittent pneumatic leg compression devices, casts, and traction devices all have been associated with an increased incidence of delirium (1, 4, 25).

Sleep deprivation. Studies have demonstrated that sleep deprivation may lead to the development of both psychosis (26) and delirium (27–30). Studies have found that the average amount of sleep in patients in an intensive care unit (ICU) is limited to 1 hour and 51 minutes per 24-hour period (31). Many factors may affect sleep in the ICU, including frequent therapeutic interventions, the nature of diagnostic procedures, pain, fear, and the noisy environment (1). Mounting data suggest that a cumulative sleep debt may not just be a cause of but may aggravate or perpetuate delirium (32–35). Among other factors, findings suggest that the dyssynchronization of the melatonin secretion rhythm commonly found among critical care patients (possibly mediated or exacerbated by the use of sedative agents) may contribute to the development of delirium (36–38).

Oversedation. Similarly, oversedation has been found to be an independent predictor of prolonged mechanical ventilation (39). Sedative agents (mostly GABA-ergic) and opioids may contribute to the development of delirium by one of five mechanisms (1): 1) interfering with physiological sleep patterns; 2) interfering with central cholinergic function muscarinic transmission at the level of the basal forebrain and hippocampus (i.e., causing a centrally mediated acetylcholine-deficient state); 3) increasing compensatory up-regulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate and kainite receptors and Ca2+ channels; 4) disrupting the circadian rhythm of melatonin release; and 5) disrupting the thalamic gating function.

Psychiatric Disorders. Certain psychiatric diagnoses, including a history of alcohol and other substance abuse, as well as depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have been associated with a higher incidence of delirium (3, 40, 41).

Pain. Data suggests that both pain and medications used for the treatment of pain have been associated with the development of delirium. Studies have demonstrated that the presence of postoperative pain is an independent predictor of delirium after surgery (42). On the other hand, the use of opioid agents has been implicated in the development of delirium (43–45). For example, opioids are blamed for nearly 60% of the cases of delirium in patients with advanced cancer (46).

Severity of underlying medical illness/comorbidities. Evidence shows that the probability of transitioning to delirium increases dramatically for each additional point in the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) severity of illness score (6). Others have also found that high medical comorbidity is an independent risk factor for the development of delirium (3, 4).

|

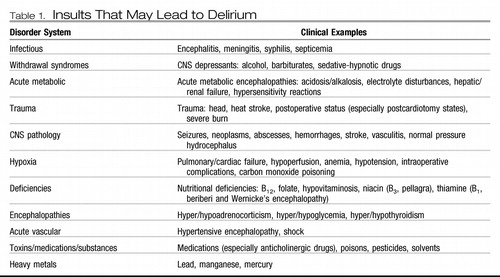

Table 1. Insults That May Lead to Delirium

Another important aspect to consider is the differential diagnosis. The symptoms of delirium vary from patient to patient and sometimes within a single patient over time. Some have suggested that there are motor variations (i.e., hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed states) regarding their presentation (47). But what a clinician needs to keep in mind is that symptoms of delirium may present like mania, psychosis, catatonia, and even depression. In fact, data suggests that nearly 40% of the times when psychosomatic medicine consultants are asked to assist in the management of depression of hospitalized medically ill patients, these subjects were, in fact, experiencing hypoactive delirium and not major depression (48, 49). Substance intoxication/abuse (particularly CNS stimulant agent intoxication [e.g., cocaine and amphetamines]) and withdrawal states (particularly from CNS depressant agents [e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates]) may all lead to various forms of delirium (usually the hyperactive type). Conversely, acute intoxication with a CNS depressant or withdrawal from a CNS stimulant may lead to hypoactive forms of delirium.

Understanding delirium is important because of its high prevalence and the increased morbidity and mortality rates associated with its development. The incidence of delirium in the ICU has been reported to be as high as 81.3% (50). Several studies have found that patients who developed delirium fared much worse than their counterparts without delirium when controlling for all other factors. One study (51) showed that the mortality rate was higher among patients with delirium (as high as 8% compared with 1% in patients without delirium). In another study, patients in the ICU who developed delirium had higher 6-month mortality rates (34% versus 15%, p=0.03) (52). Similarly, another study showed that the 90-day mortality was as high as 11% among patients with delirium, compared with only 3% among elderly patients without delirium (53). Not only is delirium associated with increased mortality, but the rate of morbidity is also increased. Multiple studies have demonstrated that patients with delirium have prolonged hospital stays (i.e., average 5–10 days longer), compared with patients with the same medical problem who do not develop delirium as a complication (50–52, 54).

Finally, the development of delirium has been associated with significant increases in the cost of delivering care. A study of cardiac surgery demonstrated that the calculated additional cost caused by the development of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery was $6,150 per patient (55). Similarly, a subsequent study of the same population demonstrated that the development of postoperative delirium nearly doubled the cost of care in cardiac valve replacement (i.e., $6,763 in patients who did not develop delirium versus $12,965 in patients who developed delirium). A study of a step-down critical care unit showed that even though only 14% of patients developed delirium, they represented 22% of ALL hospital days during the index period (54). The same study showed that patients with delirium remained hospitalized an average of 9.2 days longer than their counterparts without delirium at an average cost of $28,000 per patient. A study of patients in the ICU with delirium showed that health care costs were 31% higher than for patients with similar medical problems but without delirium (i.e., $41,836 versus $27,106 per patient) (56). In addition, in a study of hospitalized elderly patients, data show that 1) delirium is common, 2) patients with delirium had significantly higher unadjusted health care costs and survived fewer days, 3) the average costs per day among patients with delirium were 2.5-fold greater than those for patients without delirium; and 4) the total cost estimates attributable to delirium ranged from $16,303 to $64,421 per patient (57).

As can be surmised from the above facts, it is imperative to treat delirium early, but it is more important to prevent it. There are several excellent studies suggesting potential interventions for the prevention of delirium. The best nonpharmacological method is the multicomponent intervention method described below (58). With this intervention strategy a 40% reduction in the odds of developing delirium has been seen. Other nonpharmacological prevention strategies, primarily consisting of the prophylactic use of neuropsychiatric consultation in “at-risk patients” have also demonstrated a lower incidence of postoperative delirium and a reduction in associated complications (e.g., decubitus ulcers, urinary tract infections, nutritional complications, sleeping problems, and falls) (59, 60). There have also been pharmacological interventions in small, but promising studies that have demonstrated significant reductions in the development of delirium. Several studies have demonstrated that antipsychotics, given preoperatively, may reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium (61–64). Some studies have suggested that the long-term use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in at-risk populations may lower the incidence of postoperative delirium (65, 66). However, studies using short-term preoperative treatment failed to demonstrate any benefit (67, 68). A recently published article demonstrated a dramatic reduction in the incidence of postoperative delirium (3% versus 50%) in cardiac patients with the use of the novel anesthetic dexmedetomidine and avoidance of the use of more conventional GABA-ergic agents (69).

There are few conclusive studies demonstrating efficacy in treatment. Many studies using pharmacological agents have shown either conflicting findings, or the study population or data size is inadequate to allow for generalizability of the results. Thus, what follows is a basic algorithm for the prevention and management of delirium. Steps associated with robust evidence-based data are identified with an asterisk (*). The others have been developed from clinical practice or empirical data based on theoretical models. A more thorough discussion of these, along with their theoretical rationale, is beyond the scope of this commentary and can be found elsewhere (1, 2, 70–72).

| I. | Timely diagnosis

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| II. | Identify and treat underlying medical problems that may be causing or contributing to delirium in your particular patient (Table 1). The ultimate treatment of choice is the timely discovery and correction of the underlying medical causes of delirium. That is, aggressively treat infectious processes and electrolyte imbalances, correct vital signs and end-organ functioning, restore a more physiological sleep-wake cycle, minimize fear, anxiety, and pain, and manage extrinsic/environmental factors, such as lighting and noise control.* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| III. | Institute non-pharmacological treatment strategies* (based on Inouye's multicomponent intervention method for prevention of delirium in elderly patients) (58).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IV. | Consider pharmacological treatment strategies.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1 Maldonado JR: Delirium in the acute care setting: characteristics, diagnosis and treatment. Crit Care Clin 2008; 24: 657– 722Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Maldonado JR: Pathoetiological model of delirium: a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Crit Care Clin 2008; 24: 789– 856Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bellavance F: Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med 1998; 13: 204– 12Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Inouye S, Zhang Y, Jones RN, Shi P, Cupples LA, Calderon HN, Marcantonio ER: Risk factors for delirium at discharge: development and validation of a predictive model. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 1406– 1413Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Gibson GE, Peterson C: Aging decreases oxidative metabolism and the release and synthesis of acetylcholine. J Neurochem 1981; 37: 978– 984Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, Pun BT, Wilkinson GR, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW: Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology 2006; 104: 21– 6Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Milstein A, Pollack A, Kleinman G, Barak Y; Confusion/delirium following cataract surgery: an incidence study of 1-year duration. Int Psychogeriatr 2002; 14: 301– 306Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Bergmann K, Eastham EJ: Psychogeriatric ascertainment and assessment for treatment in an acute medical ward setting. Age Ageing 1974; 3: 174– 188Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Kalisvaart K, Vreeswijk R, de Jonghe JF, van der Ploeg T, van Gool WA, Eikelenboom P: Risk factors and prediction of postoperative delirium in elderly hip-surgery patients: implementation and validation of a medical risk factor model. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 817– 822Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Wahlund L, Bjorlin GA: Delirium in clinical practice: experiences from a specialized delirium ward. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10: 389– 392Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Wacker P, Nunes PV, Cabrita H, Forlenza OV: Post-operative delirium is associated with poor cognitive outcome and dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006; 21: 221– 227Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Lowery DP, Wesnes K, Ballard CG: Subtle attentional deficits in the absence of dementia are associated with an increased risk of post-operative delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007; 23: 390– 394Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Aldemir M, Ozen S, Kara IH, Sir A, Bac B: Predisposing factors for delirium in the surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care 2001; 5: 265– 270Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Cacchione PZ, Culp K, Dyck MJ, Laing J: Risk for acute confusion in sensory-impaired, rural, long-term-care elders. Clin Nurs Res 2003; 12: 340– 355Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Francis J: Three millennia of delirium research: moving beyond echoes of the past. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47: 1382Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Tuma R, DeAngelis LM: Altered mental status in patients with cancer. Arch Neurol 2000; 57: 1727– 1731Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A: The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics 2002; 43: 183– 194Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, Pereira JL, Hanson J, Suarez-Almazor ME, Bruera ED: Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 786– 794Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Ely EW: Delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2008; 12( suppl 3): S3Google Scholar

20 Plaschke K, Thomas C, Engelhardt R, Teschendorf P, Hestermann U, Weigand MA, Martin E, Kopitz J: Significant correlation between plasma and CSF anticholinergic activity in presurgical patients. Neurosci Lett 2007; 417: 16– 20Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Tune L, Carr S, Hoag E, Cooper T: Anticholinergic effects of drugs commonly prescribed for the elderly: potential means for assessing risk of delirium. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149: 1393– 1394Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Flacker JM, Wei JY: Endogenous anticholinergic substances may exist during acute illness in elderly medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: M353– M355Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Mach JR Jr, Dysken MW, Kuskowski M, Richelson E, Holden L, Jilk KM: Serum anticholinergic activity in hospitalized older persons with delirium: a preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43: 491– 495Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Kirshner M, Shen C, Dodge H, Ganguli M: Serum anticholinergic activity in a community-based sample of older adults: relationship with cognitive performance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60: 198– 203Crossref, Google Scholar

25 McCusker J, Verdon J, Caplan GA, Meldon SW, Jacobs P: Older persons in the emergency medical care system. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 2103– 2105Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Berger M, Vollmann J, Hohagen F, Konig A, Lohner H, Voderholzer U, Riemann D: Sleep deprivation combined with consecutive sleep phase advance as a fast-acting therapy in depression: an open pilot trial in medicated and unmedicated patients. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 870– 872Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Evans JI, Lewis SA: Sleep studies in early delirium and during drug withdrawal in normal subjects and the effect of phenothiazines on such states. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1968; 25: 508– 509Google Scholar

28 Johns M, Large AA, Masterton JP, Dudley HA: Sleep and delirium after open heart surgery. Br J Surg 1974; 61: 377– 381Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Lipowski ZJ: Delirium (acute confusional states). JAMA 1987; 258: 1789– 1792Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Mistraletti G, Carloni E, Cigada M, Zambrelli E, Taverna M, Sabbatici G, Ombrello M, Elia G, Destrebecq AL, Iapichino G: Sleep and delirium in the intensive care unit. Minerva Anesthesiol 2008; 74: 329– 333Google Scholar

31 Aurell J, Elmqvist D: Sleep in the surgical intensive care unit: continuous polygraphic recording of sleep in nine patients receiving postoperative care. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985; 290: 1029– 1032Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Heller SS, Frank KA, Malm JR, Bowman FO Jr, Harris PD, Charlton MH, Kornfeld DS: Psychiatric complications of open-heart surgery: a re-examination. N Engl J Med 1970; 283: 1015– 1020Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Helton MC, Gordon SH, Nunnery SL: The correlation between sleep deprivation and the intensive care unit syndrome. Heart Lung 1980; 9: 464– 468Google Scholar

34 Ito H, Harada D, Hayashida K, Ishino H, Nakayama K: Psychiatry and sleep disorders—delirium. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 2006; 108: 1217– 1221Google Scholar

35 Munoz X, Marti S, Sumalla J, Bosch J, Sampol G: Acute delirium as a manifestation of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 158: 1306– 1307Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Balan S, Leibovitz A, Zila SO, Ruth M, Chana W, Yassica B, Rahel B, Richard G, Neumann E, Blagman B, Habot B: The relation between the clinical subtypes of delirium and the urinary level of 6-SMT. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 15: 363– 366Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Olofsson K, Alling C, Lundberg D, Malmros C: Abolished circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion in sedated and artificially ventilated intensive care patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004; 48: 679– 684Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Shigeta H, Yasui A, Nimura Y, Machida N, Kageyama M, Miura M, Menjo M, Ikeda K: Postoperative delirium and melatonin levels in elderly patients. Am J Surg 2001; 182: 449– 454Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O'Connor MF, Hall JB: Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1471– 1477Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Palmstierna T: A model for predicting alcohol withdrawal delirium. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52: 820– 823Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Ritchie J, Steiner W, Abrahamowicz M: Incidence of and risk factors for delirium among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv 1996; 47: 727– 730Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Vaurio LE, Sands LP, Wang Y, Mullen EA, Leung JM: Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 1267– 1273Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Fong HK, Sands LP, Leung JM: The role of postoperative analgesia in delirium and cognitive decline in elderly patients: a systematic review. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 1255– 1266Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD: Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous systems of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2007; 21: 15– 25Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Wang Y, Sands LP, Vaurio L, Mullen EA, Leung JM: The effects of postoperative pain and its management on postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 15: 50– 59Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Centeno C, Sanz A, Bruera E: Delirium in advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med 2004; 18: 184– 194Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Meagher DJ Trzepacz PT: Motoric subtypes of delirium. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 2000; 5: 75– 85Google Scholar

48 Farrell KR, Ganzini L: Misdiagnosing delirium as depression in medically ill elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 2459– 2464Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Maldonado JR, Dhami N: Recognition and management of delirium in the medical and surgical intensive care wards. J Psychosom Res 2003; 55: 150Google Scholar

50 Ely EW, Gautam S, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Speroff T, Truman B, Dittus R, Bernard R, Inouye SK: The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intens Care Med 2001; 27: 1892– 1900Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Francis J, Martin D, Kapoor WN: A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA 1990; 263: 1097– 1101Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Dittus RS: Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA 2004; 291: 1753– 1762Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Pompei P, Foreman M, Rudberg MA, Inouye SK, Braund V, Cassel CK: Delirium in hospitalized older persons: outcomes and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42: 809– 815Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Maldonado JR, Dhami N, Wise L: Clinical implications of the recognition and management of delirium in general medical and surgical wards. Psychosomatics 2003; 44: 157– 158Google Scholar

55 Ebert AD, Walzer TA, Huth C, Herrmann M: Early neurobehavioral disorders after cardiac surgery: a comparative analysis of coronary artery bypass graft surgery and valve replacement. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2001; 15: 15– 19Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, Shintani AK, Speroff T, Stiles RA, Truman B, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW: Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 955– 962Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK: One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 27– 32Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Inouye S, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, Leo-Summers L, Acampora D, Holford TR, Cooney LM Jr: A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 669– 676Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Lundström M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, Karlsson S, Nyberg L, Englund U, Borssén B, Svensson O, Gustafson Y: Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2007; 19: 178– 186Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM: Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 516– 522Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Kalisvaart K, de Jonghe JF, Bogaards MJ, Vreeswijk R, Egberts TC, Burger BJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA: Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1658– 1666Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Larsen KA, Kelly S, Stern TA: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of peri-operative administration of olanzapine to prevent post-operative delirium in joint replacement patients, in

63 Prakanrattana U, Prapaitrakool S: Efficacy of risperidone for prevention of postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care 2007; 35: 714– 719Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Schrader SL, Wellik KE, Demaerschalk BM, Caselli RJ, Woodruff BK, Wingerchuk DM: Adjunctive haloperidol prophylaxis reduces postoperative delirium severity and duration in at-risk elderly patients. Neurologist 2008; 14: 134– 137Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Dautzenberg PL, Mulder LJ, Olde Rikkert MG, Wouters CJ, Loonen AJ: Delirium in elderly hospitalised patients: protective effects of chronic rivastigmine usage. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004; 19: 641– 644Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, Cattaruzza T, Cazzato G: Cholinesterase inhibition as a possible therapy for delirium in vascular dementia: a controlled, open 24-month study of 246 patients. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2004; 19: 333– 339Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Liptzin B, Laki A, Garb JL, Fingeroth R, Krushell R: Donepezil in the prevention and treatment of post-surgical delirium. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 13: 1100– 1106Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Sampson EL, Raven PR, Ndhlovu PN, Vallance A, Garlick N, Watts J, Blanchard MR, Bruce A, Blizard R, Ritchie CW: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil hydrochloride (Aricept) for reducing the incidence of postoperative delirium after elective total hip replacement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 22: 343– 349Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Maldonado J, Wysong A, van der Starre PJA, Miller C, Reitz BA: Dexmedetomidine and the reduction of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Psychosomatics 2009; 50: 206– 217Crossref, Google Scholar

70 APA: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium, in American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Edited by Trzepacz P. Washington, DC, APA, 1999Google Scholar

71 APA: Guideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium, in American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. Edited by Cook IA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2004Google Scholar

72 Khan RA, Kahn D, Bourgeois JA: Delirium: sifting through the confusion. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2009; 11: 226– 234Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Trzepacz PT: The Delirium Rating Scale. its use in consultation-liaison research. Psychosomatics 1999; 40: 193– 204Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Inouye S, van Dyck CH, Alessi, CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI: Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113: 941– 948Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Brown T: Basic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of delirium, in The Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient. Edited by Stoudemire A, Fogel BS, Greenberg DB, New York, Oxford Press, 2000, pp 571– 580Google Scholar

76 Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, Riker RR, Fontaine D, Wittbrodt ET, Chalfin DB, Masica MF, Bjerke HS, Coplin WM, Crippen DW, Fuchs BD, Kelleher RM, Marik PE, Nasraway SA Jr, Murray MJ, Peruzzi WT, Lumb PD; Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), American College of Chest Physicians: Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med 2002; 30: 119– 141Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Riker RR, Fraser GL, Cox PM: Continuous infusion of haloperidol controls agitation in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1994; 22: 433– 440Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Shapiro BA, Warren J, Egol AB, Greenbaum DM, Jacobi J, Nasraway SA, Schein RM, Spevetz A, Stone JR: Practice parameters for intravenous analgesia and sedation for adult patients in the intensive care unit: an executive summary. Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 1995; 23: 1596– 1600Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Tune, L. The role of antipsychotics in treating delirium. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2002. Jun [cited 4 3]; 209-12]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12003684Google Scholar

80 Maldonado JR, van der Starre PJ, Block T, Wysong A: Post-operative sedation and the incidence of delirium and cognitive deficits in cardiac surgery patients. Anesthesiology 2003; 99: 465Google Scholar

81 Lonergan E, Britton AM, Luxenberg J, Wyller T: Antipsychotics for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007: CD005594dGoogle Scholar

82 Ballard C, Hanney ML, Theodoulou M, Douglas S, McShane R, Kossakowski K, Gill R, Juszczak E, Yu LM, Jacoby R, DART-AD Investigators: The dementia antipsychotic withdrawal trial (DART-AD): long-term follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 151– 157Crossref, Google Scholar