Obesity and Psychiatric Disorders: Frequently Encountered Clinical Questions

Abstract

Obesity is a global epidemic and a health priority, and several psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, are associated with an elevated risk of comorbid obesity. Moreover, persons with psychiatric disorders often have multiple risk factors (e.g., poverty and use of psychotropic medications) for excess weight. Excess weight in turn is associated with serious health consequences, both medical and psychiatric. Mental health care professionals must be familiar with the appropriate screening and treatment strategies for obesity. The authors provide a synthesis of the epidemiology, psychiatric and medical consequences, risk factors, and management strategies for obesity in psychiatric populations, giving particular consideration to management of the psychiatric patient who experiences psychotropic-associated weight gain. To formulate answers to 10 commonly asked questions about obesity and mental health, the authors conducted a MEDLINE search of all English-language articles published between 1966 and June 2005. The search terms were obesity, overweight, body mass index (BMI), metabolism, bariatric treatment, weight-loss treatment, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, binge-eating disorder, eating disorder, and psychotropic medication. The search was supplemented with a manual review of relevant references.

It has been reported that the increasing prevalence and dispersion of obesity in the general population are commensurate with those of a communicable disease epidemic (1). Several subpopulations of psychiatric patients (e.g., those with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder) have an increased risk of overweight and obesity (2). Moreover, in many psychiatric patients risk factors tend to cluster for type 2 diabetes mellitus and other general medical disorders (3). Mortality due to a general medical condition is the most frequent cause of excess death among persons with mood and psychotic disorders (4, 5). Obesity is a well-established risk factor for many medical disorders that are differentially reported in psychiatric populations (6). Mental health care providers must be familiar with the definitions, measurements, psychiatric and medical consequences, and management strategies for obesity. Many psychiatric medications are associated with clinically significant weight gain and metabolic disturbances (2, 7). To address these issues, we review 10 questions on obesity and mental disorders that are frequently asked by mental health care providers.

To formulate answers to 10 commonly asked questions about obesity and mental health, we conducted a MEDLINE search of all English-language articles published between 1966 and June 2005. The search terms were obesity, overweight, body mass index (BMI), metabolism, bariatric treatment, weight-loss treatment, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, binge-eating disorder, eating disorder, and psychotropic medication. The psychiatric disorders were cross-listed with obesity, overweight, body mass index, bariatric treatment, and metabolism. The search was supplemented with a manual review of relevant references. In the following, “excess weight” refers to both overweight and obesity, and use of the word significant denotes statistical significance at an alpha level of 0.05 or less.

Ten frequently asked questions on obesity

1. How is obesity defined and operationalized?

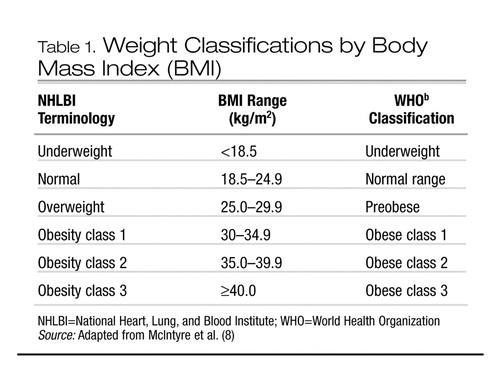

Normal body weight is defined as a body mass index (BMI) in the range of 18.5–24.9; BMI is computed as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Overweight, sometimes referred to as “pre-obese,” is defined as a BMI in the range of 25–29.9. A BMI of ≥ 30.0 is defined as obesity. Obesity has also been divided into subclasses (Table 1). Overweight in children and adolescents is frequently defined as a BMI in the 95th percentile or higher for age and sex (9).

The most frequently cited anthropometrics are weight, BMI, waist-to-hip girth ratio (WHR), and waist circumference. Total body weight and/or increase in absolute weight are the most frequently cited markers of excess weight. BMI, which takes height and weight into account, is a more useful metric. The WHR provides an estimate of the abdominal accumulation of body fat. Undesirable accumulation of body fat is defined as a WHR greater than 0.9 for males and 0.8 for females. It has been proposed that a WHR in excess of 0.85 in women and 1.00 in men is associated with alterations in glucose-insulin homeostasis and lipid-lipoprotein metabolism. The WHR is obtained by measuring the waist between the iliac crests and the lower costal margin and dividing that measure by the maximum circumference around the buttocks. It has been reported that waist circumference alone provides an adequate proxy of visceral adipose tissue. Obesity-associated morbidity is reported to be higher when the waist circumference exceeds 88 cm in females and 102 cm in males (10).

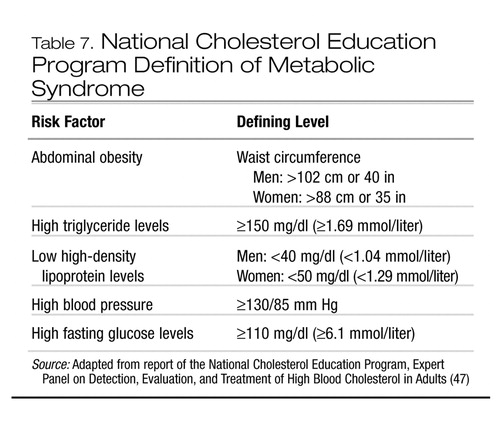

Straker and colleagues (11) evaluated the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of screening for the metabolic syndrome (see question 7) in a heterogeneous group of psychiatric patients who were treated with a variety of atypical antipsychotic agents. The overall prevalence of the metabolic syndrome was 29.2%. Abdominal obesity and elevated fasting blood glucose (>110 mg/dl) identified 100% of patients with the metabolic syndrome. These data indicate that combining measurements of waist circumference and fasting blood glucose is a reasonable and cost-effective proxy of metabolic syndrome in this patient group.

2. What is the prevalence of excess weight in the general population?

Obesity is the most common nutritional disorder in North America and globally (12). It is estimated that up to 54% of the adult population in the United States is overweight and approximately 30% are categorically obese (12–15). The estimated prevalence of obesity has been increasing significantly over the past two decades. For example, data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1998–1994) indicate that the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity was 30.5% in the 1999–2000 survey, compared with an estimate of 22.9% in the 1988–1994 survey. The prevalence of overweight also increased during this period, from 55.9% to 64.5% (14). The estimated prevalence of excess weight in pediatric populations has also more than doubled over the past three decades (16).

3. Which psychiatric populations are at risk for obesity?

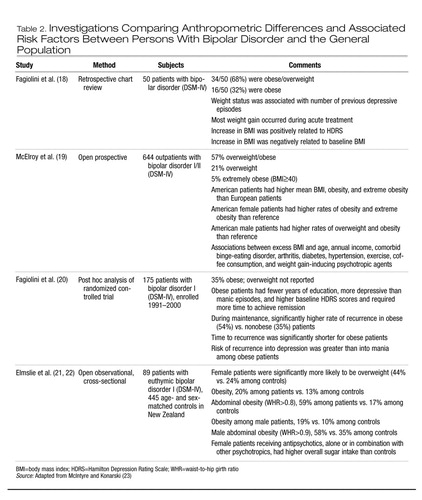

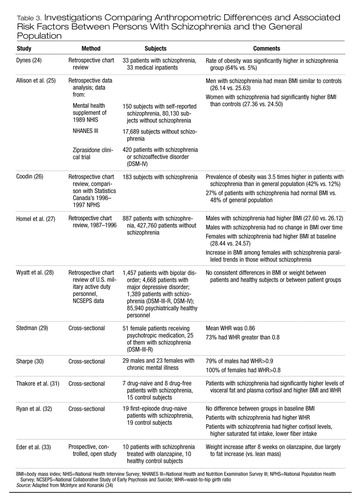

Major depressive disorder, binge-eating disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia are associated with excess weight (2, 3). A comprehensive review of the association between depression, binge-eating disorder, and obesity has been reported elsewhere (17). In Tables 2 and 3 we summarize data on obesity in patients with bipolar disorder and with schizophrenia. Taken together, contemporary studies indicate that persons with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be obese. Moreover, the WHR in both patient groups may also be higher than in the general population, indicating an abdominal distribution of excess weight.

4. What are the risk factors for obesity in psychiatric patients?

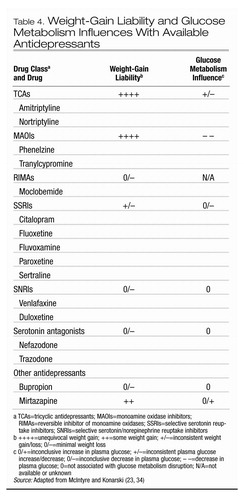

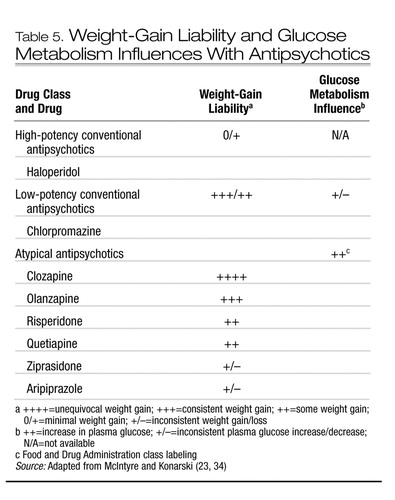

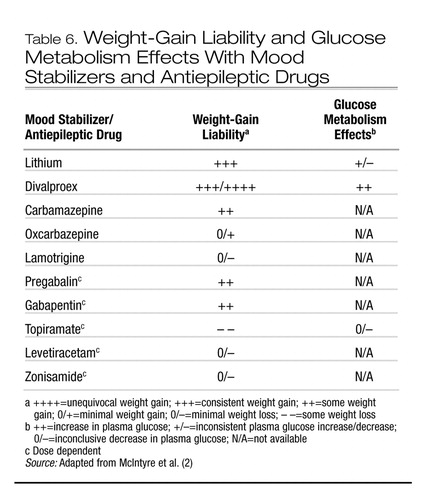

Risk factors for obesity tend to cluster in patients with psychiatric disorders, including insufficient access to primary and preventative health care, poverty, and others (3). Several psychotropic medications are particularly associated with clinically significant weight gain (Tables 4–6). The association between atypical antipsychotics and weight gain has been comprehensively examined (3). Several correlates of weight gain in patients taking antipsychotics have been suggested, although few are compelling. Younger age, improvement in psychopathology, and lower basal BMI have been the most consistently reported variables associated with antipsychotic-associated weight gain.

5. What are the mechanisms of weight gain in patients taking antipsychotic medications?

The balance between energy intake and expenditure largely determines net body weight (35). Energy expenditure can be further partitioned into resting energy expenditure and activity-related expenditure (36). Weight gain is a highly complex multifactorial phenotype with a heritability liability of approximately 70% (37). Energy intake and expenditure are tightly regulated by a panoply of central and peripheral energy homeostasis mechanisms. It is likely that antipsychotic-associated weight gain is promoted by several mechanisms, with an increase in appetite via an affinity for central appetite-stimulating systems occupying a central role (38, 39).

6. What are the medical and psychiatric consequences of obesity?

The medical complications of overweight and obesity are well established. They include, among others, osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, gallbladder disease, sleep apnea, and some forms of cancer (40). Many of these maladies are more common in some psychiatric populations (4, 5, 41, 42). The therapeutic objectives in managing severe persistent psychiatric disorders include the reduction of excess mortality. The salience of medical disorders in excess mortality of all causes calls for clinical surveillance for obesity and its associated morbidity in all psychiatric patients.

Overweight and obesity are associated with stigma, decreased self-regard, treatment noncompliance, and a variety of indexes of harmful dysfunction (e.g., work maladjustment). Obesity may also complicate treatment response and the course and outcome of some psychiatric disorders. For example, Fagiolini and associates (18, 20, 43) have reported that obesity and bipolar disorder are correlated with a longer time to recovery, higher risk of recurrence (notably for depression), suicidality, and a greater number of prior affective episodes.

7. What is the metabolic syndrome?

The term metabolic syndrome has been used interchangeably with several other monikers (e.g., syndrome X and insulin resistance syndrome). This syndrome denotes a clustering of cardiovascular and metabolic disturbances that may share a common pathophysiology. Not all affected persons manifest all dimensions of the metabolic syndrome. For example, up to 5% of the general population who do not have excess weight may be “metabolically obese” (44). It is estimated that the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the general population is approximately 20%–25%, and in some psychiatric populations, perhaps higher (45, 46). Several definitions have been formulated for the metabolic syndrome. Health care providers should be familiar with the definition proposed by the National Cholesterol Education Program (Table 7).

8. What are the management strategies for obesity?

The evidence-based guidelines issued by the National Institutes of Health (48) suggest the need for weight loss in obese persons and in overweight persons who have two or more risk factors for obesity-related diseases. The edifice for any successful weight loss program is a healthy, balanced diet, along with increased physical activity.

Some patients are at risk of rapid weight gain from taking atypical antipsychotics. For example, a post hoc analysis of data on patients treated with olanzapine (49) reveals that approximately 15% are at risk of rapid weight gain (defined as gaining 7% or more of their baseline weight within 6 weeks of initiation of therapy). These data suggest that weight gain monitoring should be particularly close during the first 2 months of administrating the medication.

It has been established that relatively modest reductions in weight are associated with clinically significant health benefits. The provision of basic education on weight management and healthy dietary choices is an inexpensive and effective intervention. Yet, unfortunately, most obese persons do not routinely receive weight loss advice from their primary health care provider (42, 50).

Screening of the patient’s dietary habits, eating behaviors, and concomitant drug and alcohol use and screening for obesity-associated morbidity and family medical history are integral components of evaluation and monitoring (51). Patients need to be informed about the differences in caloric density in commonly consumed foods and beverages and be counseled on smoking cessation and reasonable alcohol use (52). The physical and mental health benefits of weight loss need to be clearly presented along with practical resources for exercise that are accessible and affordable (3, 53, 54). Body weight, BMI, and WHR should be measured and monitored routinely, with baseline measurements and then semiannual measurements at minimum, and more frequent monitoring for patients who have experienced substantial weight gain.

9. What medications are effective for antipsychotic-associated weight gain?

Bariatric pharmacotherapy is recommended for adults who have a BMI ≥ 30 as well as for adults who have a BMI ≥ 27 along with obesity-related medical conditions (10). No pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic-associated weight gain has been proven to be reliably efficacious and safe, although several medication approaches are being studied (55, 56). The best available efficacy evidence is for sibutramine and topiramate. Amantadine, metformin, orlistat, and nizatidine are alternatives, but their use is associated with many hazards (e.g., exacerbation of psychosis) (57–74).

10. What behavioral interventions are effective for psychiatric patients?

As noted, a weight loss program should begin with a healthy, balanced diet and an increase in physical activity, along with education on nutrition, diet, the benefits of weight loss, and appropriate resources for exercise.

Several reports have examined the effectiveness of behavioral strategies for weight management in psychiatric patients (see McIntyre et al. [75] for a comprehensive review). Vreeland and colleagues (76) examined the effectiveness of a 12-week multimodal weight management program among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (intervention group, n=31; control group, n=15). All patients had been receiving an atypical antipsychotic for at least 3 months and had a BMI ≥ 26, or they had experienced a weight gain of ≥ 2.3 kg within 2 months of initiating the index medication. The program emphasized nutritional counseling, exercise, behavioral interventions, and healthy weight management techniques. At the end of the study period, patients assigned to the intervention group lost significantly more weight (mean loss, 2.7 kg or 2.7% of body weight) than patients assigned to the control group (mean gain, 2.9 kg or 3.1% of body weight). The corresponding mean change in BMI was a drop from 34.32 to 33.34 (2.8%) in the intervention group and an increase from 33.4 to 34.6 (3.6%) in the control group.

A report on the combination of exercise and the multicomponent Weight Watchers program (77) indicated that there were no statistically significant changes in BMI in patients with schizophrenia who were treated with olanzapine (n=21). Menza and colleagues (78) evaluated the effectiveness of a multimodal 12-month weight management program offered over 12 months to patients with schizophrenia who were treated with antipsychotics (n=31) who had gained significant weight. The intervention group experienced a significant loss of weight (3.0 kg) and reduction in BMI (5.1%), with favorable effects on blood pressure.

The evidentiary base supporting nonpharmacological approaches for medication-associated weight gain in psychiatric populations (76, 79–82) is sparse; this is clearly an area that requires further research. Nevertheless, the assertion that behavioral strategies are acceptable to psychiatric patients and beneficial for treating excess weight has preliminary support in the available research, and these strategies should have a salient role in the management plan.

Conclusion

The estimated prevalence of excess weight is increasing in the general population, and excess weight is particularly common in patients with mood and psychotic disorders. Several psychotropic medications, notably antipsychotics, are associated with clinically significant weight gain. Excess weight is associated with medical and psychiatric adversity, medical morbidity, and premature mortality. Patients with mood and psychotic disorders should be considered metabolically vulnerable. Routine screening, monitoring, and targeting obesity for treatment in psychiatric populations is a primary therapeutic objective.

|

Table 1. Weight Classifications by Body Mass Index (BMI)

|

Table 2. Investigations Comparing Anthropometric Differences and Associated Risk Factors Between Persons With Bipolar Disorder and the General Population

|

Table 3. Investigations Comparing Anthropometric Differences and Associated Risk Factors Between Persons With Schizophrenia and the General Population

|

Table 4. Weight-Gain Liability and Glucose Metabolism Influences With Available Antidepressants

|

Table 5. Weight-Gain Liability and Glucose Metabolism Influences With Antipsychotics

|

Table 6. Weight-Gain Liability and Glucose Metabolism Effects With Mood Stabilizers and Antiepileptic Drugs

|

Table 7. National Cholesterol Education Program Definition of Metabolic Syndrome

1 Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP: The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998. JAMA 1999; 282:1519–1522Crossref, Google Scholar

2 McIntyre RS, Mancini DA, Pearce MM, Silverstone P, Chue P, Misener VL, Konarski JZ: Mood and psychotic disorders and type 2 diabetes: a metabolic triad. Can J Diabetes 2005; 29:122–132Google Scholar

3 Keck PE, Buse JB, Dagogo-Jack S, D’Alessio DA, Daniels SR, McElroy SL, McIntyre RS, Sernyak MJ, Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC: Managing Metabolic Concerns in Patients With Severe Mental Illness. Minneapolis, Healthcare Information Programs, McGraw-Hill Healthcare Information Group, December 2003Google Scholar

4 Osby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparen P: Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm County, Sweden. Schizophr Res 2000; 45(1–2):21–28Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Osby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparen P: Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:844–850Crossref, Google Scholar

6 McIntyre RS, Mancini DA, Pearce MM, Silverstone P, Chue P, Misener VL, Konarski JZ: Mood and psychotic disorders and type 2 diabetes: a metabolic triad. Can J Diabetes 2005; 29:122–132Google Scholar

7 American Diabetes Association: Consensus Development Conference on Antipsychotic Drugs and Obesity and Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:596–601Crossref, Google Scholar

8 McIntyre RS, McCann SM, Kennedy SH: Antipsychotic metabolic effects: weight gain, diabetes mellitus, and lipid abnormalities. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:273–281Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Troiano RP, Flegal KM, Kuczmarski RJ, Campbell SM, Johnson CL: Overweight prevalence and trends for children and adolescents: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1963 to 1991. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995; 149:1085–1091Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE: Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ 1995; 311(6998):158–161Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Straker D, Correll CU, Kramer-Ginsberg E, Abdulhamid N, Koshy F, Rubens E, Saint-Vil R, Kane JM, Manu P: Cost-effective screening for the metabolic syndrome in patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1217–1221Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA: Obesity. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:591–602Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS: Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA 2003; 289:76–79Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL: Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002; 288:1723–1727Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL: Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998; 22:39–47Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL: Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002; 288:1728–1732Crossref, Google Scholar

17 McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Malhotra S, Nelson EB, Keck PE, and Nemeroff CB: Are mood disorders and obesity related? A review for the mental health professional. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:634–651Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Fagiolini A, Frank E, Houck PR, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, Buysse DJ, Ombao H, Kupfer DJ: Prevalence of obesity and weight change during treatment in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:528–533Crossref, Google Scholar

19 McElroy SL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Dhavale D, Keck PE Jr, Leverich GS, Altshuler L, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, Kupka R, Grunze H, Walden J, Post RM: Correlates of overweight and obesity in 644 patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:207–213Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ, Houck PR, Novick DM, Frank E: Obesity as a correlate of outcome in patients with bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:112–117Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Elmslie JL, Mann JI, Silverstone JT, Williams SM, Romans SE: Determinants of overweight and obesity in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:486–491Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Elmslie JL, Silverstone JT, Mann JI, Williams SM, Romans SE: Prevalence of overweight and obesity in bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:179–184Crossref, Google Scholar

23 McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ: Bipolar disorder, overweight/obesity and glucose handling disorders. Current Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

24 Dynes JB: Diabetes in schizophrenia and diabetes in nonpsychotic medical patients. Dis Nerv Syst 1969; 30:341–344Google Scholar

25 Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Heo M, Mentore JL, Cappelleri JC, Chandler LP, Weiden PJ, Cheskin LJ: The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:215–220Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Coodin S: Body mass index in persons with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:549–555Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Homel P, Casey D, Allison DB: Changes in body mass index for individuals with and without schizophrenia, 1987–1996. Schizophr Res 2002; 55:277–284Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Wyatt RJ, Henter ID, Mojtabai R, Bartko JJ: Height, weight and body mass index (BMI) in psychiatrically ill US armed forces personnel. Psychol Med 2003; 33:363–368Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Stedman T, Welham J: The distribution of adipose tissue in female in-patients receiving psychotropic drugs. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:249–250Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Sharpe JK, Hills AP: Anthropometry and adiposity in a group of people with chronic mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1998; 32:77–81Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Thakore JH, Mann JN, Vlahos I, Martin A, Reznek R: Increased visceral fat distribution in drug-naive and drug-free patients with schizophrenia. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002; 26:137–141Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Ryan MC, Flanagan S, Kinsella U, Keeling F, Thakore JH: The effects of atypical antipsychotics on visceral fat distribution in first episode, drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Life Sci 2004; 74:1999–2008Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Eder U, Mangweth B, Ebenbichler C, Weiss E, Hofer A, Hummer M, Kemmler G, Lechleitner M, Fleischhacker WW: Association of olanzapine-induced weight gain with an increase in body fat. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1719–1722Crossref, Google Scholar

34 McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ: Schizophrenia, overweight/obesity and glucose handling disorder. Current Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

35 Tappy L, Binnert C, Schneiter P: Energy expenditure, physical activity, and body-weight control. Proc Nutr Soc 2003; 62:663–666Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Speakman JR, Selman C: Physical activity and resting metabolic rate. Proc Nutr Soc 2003; 62:621–634Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Hebebrand J, Sommerlad C, Geller F, Gorg T, Hinney A: The genetics of obesity: practical implications. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25(suppl 1):S10–S18Google Scholar

38 Gale SM, Castracane VD, Mantzoros CS: Energy homeostasis, obesity, and eating disorders: recent advances in endocrinology. J Nutr 2004; 134:295–298Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Baptista T, Zarate J, Joober R, Colasante C, Beaulieu S, Paez X, Hernandez L: Drug induced weight gain, an impediment to successful pharmacotherapy: focus on antipsychotics. Curr Drug Targets 2004; 5:279–299Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH: The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA 1999; 282:1523–1529Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Lambert TJ, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C: Medical comorbidity in schizophrenia. Med J Aust 2003; 178(suppl):S67–S70Google Scholar

42 Evans DL, Charney DS: Mood disorders and medical illness: a major public health problem. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:177–180Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ, Rucci P, Scott JA, Novick DM, Frank E: Suicide attempts and ideation in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:509–514Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Ruderman N, Chisholm D, Pi-Sunyer X, Schneider S: The metabolically obese, normal-weight individual revisited. Diabetes 1998; 47:699–713Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Casey DE: Metabolic issues and cardiovascular disease in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Med 2005; 118(suppl 2):15S–22SGoogle Scholar

46 Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH: Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA 2002; 287:356–359Crossref, Google Scholar

47 National Cholesterol Education Program, Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001; 285:2486–2497Crossref, Google Scholar

48 National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Obesity Education Initiative: Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, June 1998Google Scholar

49 Kinon BJ, Kaiser CJ, Ahmed S, Rotelli MD, Kollack-Walker S: Association between early and rapid weight gain and change in weight over one year of olanzapine therapy in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25:255–258Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM: Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:565–572Crossref, Google Scholar

51 McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Misener VL, Kennedy SH: Bipolar disorder and diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment implications. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2005; 17:83–93Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB: Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 2004; 292:927–934Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Fontaine KR, Barofsky I, Bartlett SJ, Franckowiak SC, Andersen RE: Weight loss and health-related quality of life: results at 1-year follow-up. Eat Behav 2004; 5:85–88Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Avenell A, Broom J, Brown TJ, Poobalan A, Aucott L, Stearns SC, Smith WC, Jung RT, Campbell MK, Grant AM: Systematic Review of the Long-Term Effects and Economic Consequences of Treatments for Obesity and Implications for Health Improvement. Health Technol Assess 2004; 8(21)Google Scholar

55 Raison CL, Klein HM: Psychotic mania associated with fenfluramine and phentermine use. Am J.Psychiatry 1997; 154:711Google Scholar

56 Khan SA, Spiegel DA, Jobe PC: Psychotomimetic effects of anorectic drugs. Am Fam Physician 1987; 36:107–112Google Scholar

57 Baptista T: Body weight gain induced by antipsychotic drugs: mechanisms and management. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100:3–16Crossref, Google Scholar

58 James WP, Astrup A, Finer N, Hilsted J, Kopelman P, Rossner S, Saris WH, Van Gaal LF: Effect of sibutramine on weight maintenance after weight loss: a randomised trial. Lancet 2000; 356(9248):2119–2125Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Wirth A, Krause J: Long-term weight loss with sibutramine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286:1331–1339Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Henderson DC, Copeland PM, Daley TB, Borba CP, Cather C, Nguyen DD, Louie PM, Evins AE, Freudenreich O, Hayden D, Goff DC: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sibutramine for olanzapine-associated weight gain. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:954–962Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Benazzi F: Organic hypomania secondary to sibutramine-citalopram interaction. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:165Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Giese SY, Neborsky R: Serotonin syndrome: potential consequences of Meridia combined with Demerol or fentanyl. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 107:293–294Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Hedges DW, Reimherr FW, Hoopes SP, Rosenthal NR, Kamin M, Karim R, Capece JA: Treatment of bulimia nervosa with topiramate in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, part 2: improvement in psychiatric measures. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1449–1454Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Bray GA, Hollander P, Klein S, Kushner R, Levy B, Fitchet M, Perry BH: A 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of topiramate for weight loss in obesity. Obes Res 2003; 11:722–733Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Hoopes SP, Reimherr FW, Hedges DW, Rosenthal NR, Kamin M, Karim R, Capece JA, Karvois D: Treatment of bulimia nervosa with topiramate in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, part 1: improvement in binge and purge measures. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1335–1341Crossref, Google Scholar

66 McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, Keck PE Jr, Rosenthal NR, Karim MR, Kamin M, Hudson JI: Topiramate in the treatment of binge-eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:255–261Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Nickel MK, Nickel C, Muehlbacher M, Leiberich PK, Kaplan P, Lahmann C, Tritt K, Krawczyk J, Kettler C, Egger C, Rother WK, Loew TH: Influence of topiramate on olanzapine-related adiposity in women: a random, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25:211–217Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Floris M, Lejeune J, Deberdt W: Effect of amantadine on weight gain during olanzapine treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001; 11:181–182Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Cavazzoni P, Tanaka Y, Roychowdhury SM, Breier A, Allison DB: Nizatidine for prevention of weight gain with olanzapine: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 13:81–85Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Ustundag B: Nizatidine ftreatment and its relationship with leptin levels in patients with olanzapine-induced weight gain. Hum Psychopharmacol 2003; 18:457–461Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Baptista T, Hernandez L, Prieto LA, Boyero EC, de Mendoza S: Metformin in obesity associated with antipsychotic drug administration: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:653–655Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Bustillo JR, Lauriello J, Parker K, Hammond R, Rowland L, Bogenschutz M, Keith S: Treatment of weight gain with fluoxetine in olanzapine-treated schizophrenic outpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:527–529Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Heck AM, Yanovski JA, Calis KA: Orlistat: a new lipase inhibitor for the management of obesity. Pharmacotherapy 2000; 20:270–279Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Hilger E, Quiner S, Ginzel I, Walter H, Saria L, Barnas C: The effect of orlistat on plasma levels of psychotropic drugs in patients with long-term psychopharmacotherapy. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22:68–70Crossref, Google Scholar

75 McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Keck PE: Psychotropic-induced weight gain: liability, mechanisms, and treatment approaches, in Obesity and Mental Disorders. Edited by McElroy SL, Allison DB, Bray GA. New York, Taylor and Francis, 2005, pp 307–352Google Scholar

76 Vreeland B, Minsky S, Menza M, Rigassio Radler D, Roemheld-Hamm B, Stern R: A program for managing weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:1155–1157Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Ball MP, Coons V B, Buchanan RW: A program for treating olanzapine-related weight gain. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:967–969Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Menza M, Vreeland B, Minsky S, Gara M, Radler DR, Sakowitz M: Managing atypical antipsychotic-associated weight gain: 12-month data on a multimodal weight control program. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:471–477Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, Berisford MA, Goldstein D, Pashdag J, Mintz J, Marder SR: Novel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilities. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:358–363Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Holt RA, Maunder EMW: Is lithium-induced weight gain prevented by providing healthy eating advice at the commencement of lithium therapy? J Hum Nutr Diet 1996; 9:127–133Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Littrell KH, Hilligoss NM, Kirshner CD, Petty RG, Johnson CG: The effects of an educational intervention on antipsychotic-induced weight gain. J Nurs Scholarsh 2003; 35:237–241Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Ball MP, Coons VB, Buchanan RW: A program for treating olanzapine-related weight gain. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:967–969Crossref, Google Scholar