Sexual Dysfunction

Abstract

Sexual dysfunction encompasses disorders of the sexual response cycle or sex-related pain. Disorders of desire include hypoactive sexual desire disorder and sexual aversion disorder. Disorders of arousal include male erectile disorder and female arousal disorder. Disorders of orgasm include premature ejaculation, female orgasmic disorder, and male orgasmic disorder. Sexual pain disorders include vaginismus and dyspareunia. In recent years, the treatment of sexual dysfunction has shifted from mostly psychosocial interventions, such as sex therapy, to the use of recently developed biochemical interventions, such as the phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. However, the increased focus on the medical treatment of erectile problems has been accompanied by a neglect of the biopsychosocial factors that affect the couple. This clinical synthesis provides up-to-date information on evaluating individuals and couples and on empirically based treatments. Each of the sexual disorders will be discussed from the phenomenological, etiological, and therapeutic angles.

The identification of sexual dysfunction has long been a challenging issue. According to a 2000 survey, the prevalence of sexual disorders is 43% in women and 31% in men (1). Yet a 1999 survey of patients revealed that 71% of respondents believed that physicians would dismiss concerns about sexual problems, and 68% were afraid of embarrassing their physicians by discussing sexual dysfunction (2). Clinician- and system-related barriers no doubt also have a role in preventing open communication between clinicians and patients. Such barriers include discomfort with the subject, awkwardness with language, fear of offending the patient, confidentiality, documentation of details in medical records, and legal risks.

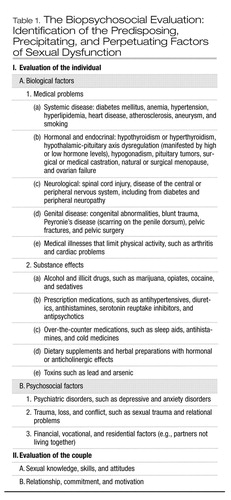

The biopsychosocial model of evaluating sexual disorders provides for a broad assessment of significant factors that interfere with sexual functioning (Table 1). Biological factors include medical problems and the effect of substances such as medications, alcohol, and illicit drugs. Psychiatric disorders clearly can have an impact on a couple’s ability to achieve a satisfying sexual relationship. Psychosocial factors include conflict within the couple as well as individual histories of trauma and loss. This model lends itself to approaches that enable the individual or the couple to fully benefit from biological interventions, psychosocial interventions, or both.

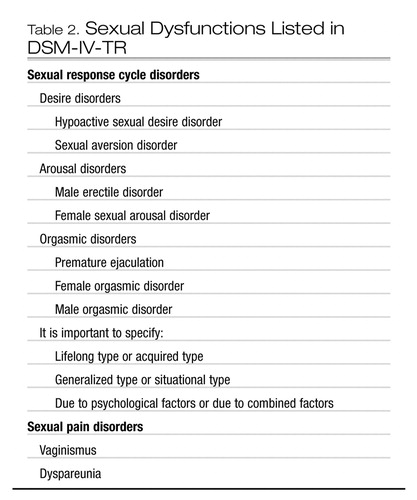

DSM-IV-TR identifies four phases of the sexual response cycle: desire, excitement (or arousal), orgasm, and resolution. Sexual dysfunction is categorized according to the first three of these phases in addition to sexual pain (Table 2). Because this clinical synthesis focuses on sexual dysfunction, the paraphilias and gender identity disorders are not covered. The reader is encouraged to seek introductory information about these disorders in the references listed (3, 4).

Sexual desire disorders

Desire or libido is characterized as the wanting of sexual intimacy and physical involvement. DSM-IV-TR lists two sexual desire disorders: hypoactive sexual desire disorder and sexual aversion disorder. These disorders, along with disorders of increased sexual activity or desire, are discussed briefly below.

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder is defined as a persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of desire for sexual activity, resulting in marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. The prevalence of the disorder is about 15% in men and about 33% in women, making it the most common sexual disorder in women (5). As individuals advance in age, the prevalence tends to decrease for women and increase for men; this phenomenon is not fully understood (5).

In diagnosing hypoactive sexual desire disorder, it is important to rule out the biological factors—medical conditions and substance-related conditions—that can reduce sexual desire. Psychosocial factors that can reduce sexual desire include sexual trauma such as incest, sexual abuse, or rape; relational factors such as mistrust or conflicts; fatigue; financial or vocational stress; and family problems. Axis I psychiatric conditions that affect desire include major depressive disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, schizophrenia, and other depressive and anxiety disorders. Negative sexual experiences and sexual disorders such as dyspareunia may also have a negative effect on desire. Certain phases of the female reproductive cycle, such as postpartum states, lactation, and menopause, are associated with low desire (6). General medical conditions such as anemia, hypertension, diabetes, thyroid problems, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, hyperprolactinemia, and the posthysterectomy state can affect desire as well. It is possible that low testosterone levels in women can contribute to hypoactive sexual desire disorder, although this is a controversial issue. Medications that can interfere with sexual desire include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antihypertensive agents, estrogens, and progestins. Chronic use of substances such as heroin or alcohol can contribute significantly to the demise of sexual appetite.

The treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder is also biopsychosocial in approach. Among the biological factors, one must address medical problems, medications, or substance abuse that may be decreasing sexual desire. Medications used in treatment include phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors, such as sildenafil, especially when hypoactive sexual desire disorder coexists with arousal disorders (7). Hormones prescribed for hypoactive sexual desire disorder include topical or transdermal testosterone (8) and estrogen replacement therapy around menopause. Sustained-release bupropion showed effectiveness in about 29% of nondepressed women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder at doses of 300 mg per day (9). Another biological intervention is the use of vacuum devices such as the Eros Clitoral Therapy Device (Eros-CTD—a vacuum device that has received approval from the Food and Drug Administration), which can promote desire (10). Psychosocial treatments start with encouraging sex education and self-exploration. Psychotherapy includes individual psychodynamic therapy, individual cognitive behavior therapy, and sex therapy with the couple. The impact of lack of desire on the partner, often leading to long-standing relational conflicts, cannot be overstated. Couples therapy within the context of sex therapy can be helpful in mitigating the impact of hypoactive sexual desire disorder on the partner.

Sexual aversion disorder

Sexual aversion disorder is defined as the persistent or recurrent aversion to and avoidance of genital sexual contact with a sexual partner, resulting in marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. This rare disorder is thought to be more common in women than men. Etiological factors are similar to those of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Sexual aversion disorder has a high incidence among patients with anorexia nervosa (11). A Brazilian study found that sexual aversion disorder is the most common sexual disorder in patients with panic disorder (12). The treatments are also similar to those for hypoactive sexual desire disorder. In addition, case reports have demonstrated the effectiveness of desensitization using behavior therapy (13).

Disorders of increased sexual activity or desire

Although disorders of this type are not listed in DSM-IV-TR, it has been proposed that the diagnosis of hyperactive sexual desire disorder be added to the sexual desire disorders to include them (14). Three models have been proposed over the years for hyperactive sexual behavior, explaining increased and repeated sexual activity that interferes with functioning as an addiction, as a compulsion, or as an impulse control disorder (15). Biopsychosocial treatment modalities such as SSRIs, naltrexone, self-help groups, and group therapy have shown some efficacy. More studies are needed to develop a better understanding of this type of disorder.

Sexual arousal disorders

Arousal or excitement is characterized by the development of pelvic vasocongestion leading to erections in men, and to lubrication, swelling, and vaginal elongation in women. DSM-IV-TR lists two disorders of arousal: male erectile disorder and female sexual arousal disorder.

Male erectile disorder

Normal erectile physiology is mediated by the release of nitric oxide secondary to parasympathetic stimulation, leading to cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation and penile engorgement. Disruption of this process leads to male erectile disorder (16).

Male erectile disorder is defined as an inability to attain or maintain an erection for the completion of sexual activity, causing marked distress and interpersonal difficulties. This condition may be lifelong or acquired, and generalized or situational. Many men are affected by male erectile disorder, with prevalence estimates ranging from 10% to 52%; prevalences are higher among older men (5). Male erectile disorder may be caused by medical or psychological factors, singly or in combination. Medical causes include neuropathic, vasculogenic, and endocrinological disorders, acquired conditions such as fibrosis of the corpus spongiosum, and concomitant medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease and morbid obesity. Male erectile disorder may be the presenting symptom for a general medical condition such as diabetes mellitus or hypothyroidism. Substances such as alcohol, opiates, and prescription medications can have a marked effect on erectile function. Psychiatric causes include mood disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, and performance anxiety. Male erectile disorder may also be caused by increased stress or relational issues.

Prior to treating male erectile disorder, any associated medical conditions or substances that might interfere with erectile function must be identified and addressed. Biological treatments include medical and surgical options. Medical treatment has primarily revolved around the use of PDE-5 inhibitors, which include sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil. All three have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of male erectile disorder, and all are contraindicated with the use of nitrates. Other pharmacological agents include intraurethral suppositories and intracavernosal injections of alprostadil. Surgical intervention involves placement of a penile prosthesis. Nonsurgical interventions include vacuum constriction devices. Couples counseling and the use of sex therapy with sensate focus exercises are key psychosocial approaches to the treatment of male erectile disorder.

Female sexual arousal disorder

Female sexual arousal disorder is defined as an inability to attain and/or maintain vaginal lubrication, vaginal elongation, and engorgement of the external genitalia for the completion of sexual activity, causing marked distress and interpersonal difficulty. The prevalence of the disorder is 20% (2).

Unlike male erectile disorder, the etiology of female sexual arousal disorder is not well understood. However, a significant association with sexual trauma has been established. As with male erectile disorder, etiologies include neuropathic, vasculogenic, and endocrinological disorders, acquired conditions such as surgical castration, concomitant medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease, and substance use. Psychosocial issues must also be ruled out.

Primary treatment options include addressing any underlying medical conditions and the effects of any substances used. It may be important to reestablish a normal hormonal milieu with hormone replacement therapy. The use of PDE-5 inhibitors has shown some limited benefit in premenopausal women; greater efficacy was demonstrated in postmenopausal women, especially when the sexual arousal disorder was associated with low desire (17). In addition, the Eros-CTD may be used to treat the symptoms of female sexual arousal disorder (10). Individual psychotherapy may also be necessary, especially if there is a history of sexual trauma. Couples therapy and/or sex therapy can be helpful in addressing relational issues, enhancing intimacy, and providing a medium for improvements in technique and communication.

Orgasmic disorders

Orgasm is characterized by pleasurable rhythmic contractions within the sex organs. DSM-IV-TR lists three disorders of orgasm: premature ejaculation, female orgasmic disorder, and male orgasmic disorder.

Premature ejaculation

Premature ejaculation is defined as persistent or recurrent ejaculation with minimal sexual stimulation or before, on, or shortly after penetration and before the person wishes it, resulting in marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. Recent sexual behavior surveys revealed that one-third of men experienced recurrent premature ejaculation, making it the most common sexual disorder in men (5). Hereditary factors, less frequent intercourse, over-the-counter cold pills, cigarette smoking, chronic prostatitis and urethritis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, arteriosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, pelvic and spinal cord injuries, polyneuritis, and polycythemia have been thought to be associated with premature ejaculation. However, more studies are needed to clarify the etiology. Psychiatric disorders, particularly panic disorder and social phobia, have been associated with premature ejaculation (12). Psychosocial factors include performance anxiety and relational problems.

The treatment of premature ejaculation begins with evaluation and treatment of any medical and substance-related factors. Common practical interventions include the use of condoms, masturbation 1–2 hours before sexual activity, and utilizing the partner-on-top sexual position. Biological interventions include SSRIs (6–12 hours before intercourse or fluoxetine 90 mg weekly), tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., clomipramine 50 mg 2–12 hours before intercourse or daily), topical anesthetic agents (lidocaine or prilocaine 2.5%), and PDE-5 inhibitors (as sole agents or in combination with SSRIs) (18). Psychosocial interventions include behavior therapy (start-stop method, squeeze method, or biofeedback), couples and/or sex therapy, and individual psychotherapy.

Male orgasmic disorder

Male orgasmic disorder is defined as persistent or recurrent delay in or absence of orgasm following a normal sexual excitement phase during sexual activity, resulting in marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. Sexual behavior surveys have estimated that approximately 8% of men experience orgasmic difficulties (5), making male orgasmic disorder the least common sexual disorder in men. Clinicians are encouraged to investigate and rule out retrograde ejaculation, which is often misdiagnosed as male orgasmic disorder. Biological factors contributing to male orgasmic disorder include general medical conditions such as diabetes, arteriosclerosis, low testosterone levels, vascular and pelvic pathology, and the use of substances such as marijuana and alcohol. Thioridazine has been implicated in orgasmic difficulties in patients with schizophrenia (19). Obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder seem to be more associated with orgasmic disorders in men than in women.

The biopsychosocial treatment of male orgasmic disorder revolves around the management of medical and substance-related disorders in addition to individual and couples/sex psychotherapy. Promising results have been shown with low doses of antiprolactin agents such as cabergoline prior to intercourse (20).

Female orgasmic disorder

Female orgasmic disorder is defined as the persistent or recurrent delay in or absence of orgasm following a normal sexual excitement phase, resulting in marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. It has been estimated that approximately 24% of women experience orgasmic difficulties at some point in their lives (5), making it the second most common sexual disorder in women after hypoactive sexual desire disorder. It is essential that the adequacy of sexual arousal (excitement) be evaluated before making this diagnosis. It is also important to rule out the presence of coexisting sexual disorders such as desire or arousal problems.

Biological illnesses contributing to female orgasmic disorder include diabetes and diabetic neuropathy, hormonal deficiencies, heart, liver, and kidney disease, and pelvic conditions such as spinal cord injuries and damage to pelvic arteries or nerves as a result of pelvic injury or surgery. Substances such as alcohol, marijuana, SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines are known to delay or inhibit orgasm. Depressive and anxiety symptoms can also affect a woman’s ability to attain orgasm. Psychosocial factors include poor sexual stimulation, relational difficulties, low self-esteem or poor body image, and unresolved emotional or sexual trauma.

Treatment approaches begin with management of medical conditions and substance-related disorders when necessary. Innovative treatments include use of the Eros-CTD (10), sacral neuromodulation using an implanted neurostimulator to stimulate the roots of S2 through S4, and Kegel exercises. PDE-5 inhibitors have shown varied results in the treatment of female orgasmic disorder. Psychosocial interventions such as individual and couples/sex psychotherapy have demonstrated efficacy. The use of innovative medical treatments such as antiprolactin agents has shown promising results in both hyperprolactinemic and normoprolactinemic women (20).

Sexual pain disorders

Pain related to sexual activity is classified by DSM-IV-TR into two main disorders: vaginismus and dyspareunia.

Vaginismus

Vaginismus is defined as recurrent or persistent involuntary spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina that interferes with sexual intercourse, resulting in marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. This involuntary, spasmodic contraction of the pelvic floor muscles (the pubococcygeus, levator ani, and related muscles) leads to the obstruction of the vaginal introitus, making penetration difficult or impossible. Data on the prevalence of vaginismus are scarce, although some sexual dysfunction clinics have reported that 12%–17% of female patients presented with this complaint (21). Etiological factors are primarily psychological and developmental in nature. Sexual trauma, conditioned association with pain or fear of penetration, and relational difficulties have all been implicated in vaginismus (22).

Treatment of vaginismus includes muscle strengthening exercises as well as psychotherapeutic interventions such as couples/sex therapy (23), and cognitive behavior therapy (24).

Dyspareunia

Dyspareunia is recurrent or persistent genital pain associated with sexual intercourse in either a male or a female. By definition, it is not caused by vaginismus or lack of lubrication, and it results in marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. Prevalence figures vary widely, depending on the definition used and population studied; prevention of intercourse occurs in about 10% (25). There is a high degree of overlap in the biological and psychological factors causing dyspareunia. It is important to include the impact of both sets of factors during the evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia, because the same factors can be expected to perpetuate other sexual problems (26). Biological factors include anatomical, inflammatory, and allergic illnesses of the vulva, vagina, and pelvis. Vaginal dryness, radiation therapy, and surgery can all contribute to dyspareunia. Substances such as antihistamines and marijuana have also been implicated. Psychosocial factors include a history of sexual trauma, body image problems, and relational difficulties.

The treatment of dyspareunia requires careful evaluation of all of the factors listed above and management of any underlying medical and substance-related disorders. Kegel exercises, electrical stimulation of the vestibular area and vaginal introitus, topical nitroglycerin (for vulvodynia), couples/sex therapy, and individual psychotherapy have been used in the treatment of dyspareunia as well.

Conclusion

It is critical that we as mental health clinicians appropriately identify and treat sexual dysfunction. Such disorders are clearly underdiagnosed, yet they cause significant physical, emotional, and interpersonal distress in patients. The importance of open-mindedness, empathic communication, and a nonjudgmental demeanor cannot be overstated. The thorough use of a biopsychosocial approach to the diagnostic workup and treatment of sexual disorders ensures that no correctable causes are missed and that all effective treatment modalities are used. In addition, the course of treatment is well served by the use of outcome measures such as structured interviews and rating scales to monitor symptom severity and treatment response (27). Patients with sexual disorders should not suffer in silence. An approach that incorporates all of these elements can lead to the best possible outcomes for them.

|

Table 1. The Biopsychosocial Evaluation: Identification of the Predisposing, Precipitating, and Perpetuating Factors of Sexual Dysfunction

|

Table 2. Sexual Dysfunctions Listed in DSM-IV-TR

1 Rosen RC: Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in men and women. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2000; 2:189–195Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Marwick C: Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. JAMA 1999; 281:2173–2174Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Kafka MP: Paraphilia-related disorders: common, neglected, and misunderstood. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1994; 2(1):39–40; discussion 41–42Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Zucker KJ: Gender identity development and issues. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2004; 13:551–568, viiCrossref, Google Scholar

5 Laumann EO, Paik AM, Rosen RC: Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999; 281:537–544Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Warnock JJ: Female hypoactive sexual desire disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. CNS Drugs 2002; 16:745–753Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG: SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther 2002; 28(suppl 1):143–153Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, Casson PR, Buster JE, Redmond GP, Burki RE, Ginsburg ES, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR, Caramelli KE, Mazer NA: Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:682–688Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Segraves RT, Croft H, Kavoussi R, Ascher JA, Batey SR, Foster VJ, Bolden-Watson C, Metz A: Bupropion sustained release (SR) for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in nondepressed women. J Sex Marital Ther 2001; 27:303–316Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Billups KL, Berman L, Berman J, Metz ME, Glennon ME, Goldstein I: A new non-pharmacological vacuum therapy for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther 2001; 27:435–441Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Raboch JS, Faltus F: Sexuality of women with anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:9–11Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Figueira I, Possidente E, Marques C, Hayes K: Sexual dysfunction: a neglected complication of panic disorder and social phobia. Arch Sex Behav 2001; 30:369–377Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Finch S: Sexual aversion disorder treated with behavioural desensitization. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:563–564Google Scholar

14 IsHak WW, Amiri SR, Mikhail AA, Berman LA: Sexual medicine course. Presented at the 158th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Atlanta, May 21–26, 2005Google Scholar

15 Gold SN, Heffner CL: Sexual addiction: many conceptions, minimal data. Clin Psychol Rev 1998; 18:367–381Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Lue TF: Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1802–1813Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Berman JR, Berman LA, Toler SM, Gill J, Haughie S; Sildenafil Study Group: Safety and efficacy of sildenafil citrate for the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol 2003; 170:2333–2338Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Waldinger MD: Lifelong premature ejaculation: from authority-based to evidence-based medicine. BJU Int 2004; 93:201–207Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Aizenberg D, Shiloh R, Zemishlany Z, Weizman A: Low-dose imipramine for thioridazine-induced male orgasmic disorder. J Sex Marital Ther 1996; 22:225–229Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Melmed S, IsHak WW, Berman D: Use of cabergoline for the treatment of anorgasmia or delayed orgasm, in Orgasmic Disorders, Sexual Medicine Course. Edited by IsHak WW. Presented at the 158th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Atlanta, May 21–26, 2005Google Scholar

21 Spector IP, Carey MP: Incidence and prevalence of the sexual dysfunctions: a critical review of the empirical literature. Arch Sex Behav 1990; 19:389–408Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalife S, Cohen D, Amsel R: Vaginal spasm, pain, and behavior: an empirical investigation of the diagnosis of vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav 2004; 33:5–17Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Biswas A, Ratnam SS: Vaginismus and outcome of treatment. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1995; 24:755–758Google Scholar

24 Kabakci E, Batur S: Who benefits from cognitive behavioral therapy for vaginismus? J Sex Marital Ther 2003; 29:277–288Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Basson R: Women’s sexual dysfunction: revised and expanded definitions. CMAJ 2005; 172:1327–1333Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Heim LJ: Evaluation and differential diagnosis of dyspareunia. Am Fam Physician 2001; 63:1535–1544Google Scholar

27 Berman L, Berman J, Zierak MC, Marley C: Outcome measurement in sexual disorders, in Outcome Measurement in Psychiatry: A Critical Review. Edited by IsHak WW, Burt T, Sederer LI. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2002Google Scholar