Eating Disorders

Abstract

The diagnostic category of eating disorders encompasses anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and the heterogeneous group of eating disorders not otherwise specified, most prominent among which is binge-eating disorder, currently detailed in research criteria in DSM-IV-TR and under consideration for inclusion as a separate diagnosis. In recent decades researchers have increasingly appreciated the multifaceted contributions to the etiology and pathogenesis of eating disorders, including genetic, familial, developmental, and psychosocial influences. Comorbidity with other axis I and axis II disorders is common, and medical comorbidity is of particular significance because of marked nutritional impairments that often accompany these disorders. Although the evidence-based treatment literature is sparse, particularly for anorexia nervosa, progress has been made with respect to nutritional, psychosocial, and psychopharmacological interventions for these disorders, and a growing consensus among clinicians has resulted in practice guidelines that attend to each of these dimensions.

Clinical context

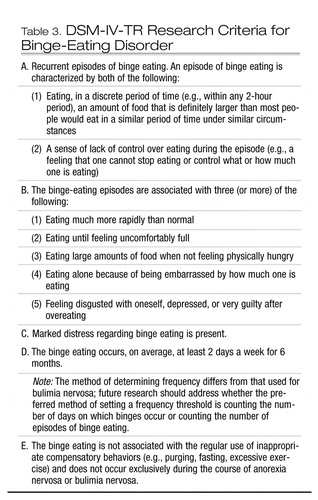

Eating disorders primarily affect women, although in clinical settings males constitute some 5%–10% of cases of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and about 30% of cases of binge-eating disorder (1–3). Significantly impaired patients with mixed signs and symptoms of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and/or binge-eating disorder comprise a large percentage of patients seen in treatment centers. Currently, binge-eating disorder is classified under the category of eating disorders not otherwise specified, but it may attain separate diagnostic status in future editions of DSM.

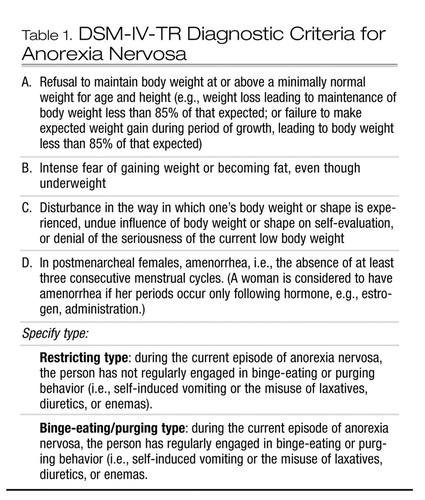

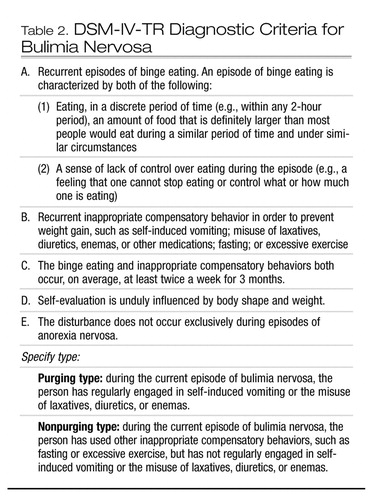

The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. For these disorders, developmental vulnerabilities such as shyness and childhood anxiety disorders (4), perfectionism (5), obsessive-compulsive traits (6), early mood disorders (7), familial transmission (8, 9), physical impairments (10, 11), and high psychiatric comorbidity (12–14) inform treatment. In the bulimia and binge-eating subgroups in particular, co-occurring substance use disorders (14) and a propensity toward obesity (2) are also relevant. Treatment and prognosis also vary with coexisting personality traits and disorders. The prognosis is most promising for patients who are otherwise high functioning and worse for those who are highly disturbed, constricted, and avoidant and those who are highly disturbed, impulsive, and emotionally dysregulated (15). For patients with long-term cases, chronic medical problems, among them osteoporosis and cardiovascular problems, become especially important. Obesity and its complications are prevalent among patients with binge-eating disorders (2).

Treatment often requires interdisciplinary care, with primary care physicians, nurses, registered dieticians, psychologists, social workers, and a variety of ancillary therapists working with the psychiatrist. Inpatient treatment facilities that specialize in the treatment of eating disorders are not abundant, and many areas lack treatment programs for eating disorders. Geographic and/or financial constraints often limit access to treatment options for patients and their families and clinicians.

Since most cases of anorexia nervosa and many cases of bulimia nervosa begin in the early to mid-teens, families are vitally concerned; they must always be considered and involved, and they are sometimes deputized to serve as members of the treatment team (16). Families are understandably distressed by the potential lethality of these conditions; death from suicide and malnutrition are potential outcomes in young women with eating disorders (17–19).

Given the demographics of patients with eating disorders, issues of concern to adolescents in particular and women of all ages are also of prime importance in treatment. In vulnerable adolescents facing anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, these pressures produce negative self-evaluations regarding appearance, fat phobias, and a drive toward self-starvation, purging, and excessive exercise. For those with binge-eating disorders, satisfying food cravings to salve states of emotional dysregulation may lead to significant obesity and self-disparagement.

Treatment strategies and evidence

Treatment plans should include assessment and treatment of several problem sets: physiological impairments; behaviors that maintain eating disorders, such as restrictive eating, excessive exercise, binge eating, and purging; self-endangering attitudes, thoughts, and emotions that sustain the disorders; and co-occurring psychiatric disorders (20). In treating anorexia nervosa especially, key initial tasks may include enhancing the patient’s motivation, involving the patient in treatment despite his or her ambivalence, and engaging the family’s assistance in conducting treatment. Although motivational interviewing techniques used in substance use disorders are being examined for their potential utility in increasing readiness for change among patients with eating disorders, the effectiveness of such techniques remains to be demonstrated (21).

The extent of the initial medical workup depends on the patient’s degree of nutritional impairment. Along with the usual metabolic measures, such as CBC, electrolytes, magnesium, calcium, liver function tests, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone, current recommendations sometimes include complement factor 3, a sensitive measure known to indicate malnutrition even when other parameters are normal (22). For thin patients, an electrocardiogram is recommended, and for those showing any cardiovascular signs or symptoms, a cardiac ultrasound may be considered (23). A bone density scan is recommended because osteopenia may occur within a year after onset of amenorrhea (24). Demonstrating early osteopenia may help motivate wavering patients. Psychological assessment should include family members whenever feasible.

Treating anorexia nervosa

Although few controlled clinical trials have been conducted (20, 25), numerous observational studies suggest that initial treatment should focus on refeeding (20, 26, 27). Ambulatory treatment usually requires an interdisciplinary team that includes a general physician and a registered dietician who will monitor weight and laboratory indicators if the psychiatrist does not routinely perform these functions. Initial caloric intake should be tolerable to the patient but increased every few days to ensure a weight gain of 1–2 pounds per week (20). Controlled studies show that family involvement in treatment improves outcomes for younger patients, except when highly dysfunctional family patterns preclude such involvement (28, 29).

The decision about when to hospitalize a patient with anorexia nervosa depends on specific physiological and psychiatric status, patient and family motivation and ability to adhere to weight-gain programs, and personal and local resources. Indications for hospitalization and other settings of care are detailed in APA’s Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders (20). Especially for patients whose initial weight is 25% or more below expected weight but also for patients at higher weight levels, depending on a comprehensive assessment of psychiatric and medical circumstances, hospitalization is often necessary to ensure adequate intake and to limit physical activity. In younger children and adolescents, hospitalization should be considered even earlier if the patient is losing weight rapidly, before too much weight is lost, since early intervention may avert rapid physiological decline and loss of cortical white and gray matter (20). Generally, specialized eating disorders units yield better outcomes than general psychiatric units because of nursing expertise and effectively conducted protocols (30). One study suggested that short-term outcomes for involuntarily hospitalized patients are similar to those for voluntarily admitted patients (31). Higher rates of relapse and rehospitalization have been shown to occur when patients are prematurely discharged from inpatient care (32). Since weight gains of more than 2–4 pounds per week may be physiologically unsafe, patients who need to gain 20–30 pounds to restore health may require 2–3 months of hospital treatment. Partial hospitalization programs have been found to be effective in direct relation to their intensity: 8-hour, 5-day-a-week programs may approach inpatient programs in effectiveness, whereas programs that involve fewer hours and/or fewer days per week are much less effective (33, 34). In fact, however, few partial hospitalization programs specialized for treatment of eating disorders exist.

For acutely thin patients with anorexia nervosa, there have been few controlled medication studies to guide treatment. For patients treated in well-implemented inpatient programs, adding a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) provides no advantage for weight gain or reduction of hospital stay (35, 36). Several small open-label studies (37–39), the largest of which involved 20 patients, and one small controlled trial comparing olanzapine and low-dose chlorpromazine (40) suggest that low doses of atypical antipsychotic medications such as olanzapine (2.5 to 15 mg/day) may improve weight gain and psychological indicators, but good controlled studies are lacking. With regard to psychotherapy, a recent small controlled study suggests that although dropout rates were substantial for all treatments, for acutely ill patients neither cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) nor interpersonal psychotherapy was superior to a well-conducted manualized nonspecific supportive clinical management based on empathic care, nutritional education, and advice (41).

In dealing with the osteopenia and osteoporosis resulting from anorexia nervosa, the only intervention shown to potentially reverse bone loss is nutritional rehabilitation during the period of bone growth, ensuring sufficient dietary protein, carbohydrates, fats, calcium, and vitamin D (42). Supplemental estrogen-progestins (43), calcium, and/or vitamin D have not been shown to meaningfully reverse skeletal deterioration but are often prescribed in routine practice. Interventions for bone revitalization using recombinant human insulin-like growth factors (IGF) (44) and biphosphonates (24, 45) are being investigated but cannot be recommended for routine clinical use.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, severe mood disorders, and/or substance dependence, require modifications of psychiatric medications and psychotherapies.

A controlled trial has shown that after sufficient weight restoration has occurred to permit return to ambulatory aftercare, fluoxetine, averaging 40 mg/day, may help avert subsequent weight loss, depression, and rehospitalization (46). Another controlled study demonstrated that although dropout rates were high, CBT after weight gain may reduce relapse (47). In controlled trials with adult patients, other psychotherapies, including focal psychoanalytic and family therapy, have proved better than low-contact treatment (48). For younger patients, family involvement is always required, and family therapy clearly shows advantage for patients 18 years of age or younger (49). Recovery is often prolonged even in the best of situations. Full psychosocial recovery may take 5–7 years, with treatment continuing long after weight is restored (50, 51).

Treating bulimia nervosa

Both psychotherapeutic and medication treatments are available for treating bulimia nervosa, and some studies suggest that combining CBT and an SSRI yields the best results (52). Available evidence supports CBT-based treatments as the most effective single approach (53, 54), but many psychiatrists are not well trained in this area. Controlled studies show that both individual and group CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy are effective in treating bulimia nervosa (55), and dialectical behavior therapy focusing on emotion regulation skills has been shown to result in significant improvement in binging and purging behavior compared with waiting-list control subjects (56). CBT either alone or in combination with nutritional therapy was more effective than nutritional therapy alone or a control support group (57). In cases where clinical complexity does not immediately mandate more intensive interventions, self-management strategies employing written, Web-based, or CD-ROM-based CBT-oriented manuals (58–63) may effectively help some patients with bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. However, limitations are evident; many patients do not complete these trials (64), and many who do complete them ultimately seek professional treatment (58). Adding fluoxetine to self-help manual-based interventions may yield better outcomes than either treatment alone (65).

Among patients who failed an initial course of CBT, a small controlled study showed that those who were subsequently assigned to a fluoxetine group did better than those who received placebo (66). However, high dropout and low abstinence rates have been seen among patients who underwent a trial of interpersonal psychotherapy or medication management after failing CBT (67). For relapse prevention, scheduling regular visits is recommended, since simply telling successfully treated patients with bulimia nervosa to come back if they have additional problems appears ineffective as a relapse prevention technique (68).

Various medications have been used in treating bulimia nervosa. SSRIs have long been considered the gold standard, particularly fluoxetine, for which the largest controlled studies have been conducted (69). With fluoxetine, the higher dose levels usually used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorders (typically 60 mg) are more effective than the lower doses usually effective for depression (typically 20 mg). Early smaller series showed effectiveness for tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, which are now rarely used. These medications are no longer recommended as first-line treatments. Other classes of agents have been investigated, largely in relatively small industry-sponsored studies. In double-blind studies, inositol (which has also been effective in treating depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder) (70), ondansetron (71), and topiramate (72, 73), and, in open trials, the selective noradrenergic receptor inhibitor (SNRI) reboxetine (not available in the United States) (74, 75) have all been reported to be effective in treating bulimia nervosa.

Treating eating disorder not otherwise specified

Within this heterogeneous category, binge-eating disorder merits particular attention. Interpreting treatment studies of binge-eating disorder requires caution, since the symptoms of this disorder are often labile, and high placebo response rates are frequently seen.

CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy have been studied most extensively in binge-eating disorder, and both appear to do reasonably well at keeping patients in treatment. Results of psychosocial treatments resemble those for bulimia nervosa (76). Treatment of binge-eating disorder often entails concurrent interventions to address comorbid obesity, usually involving behaviors, exercise, and diet. Some research shows that patients with binge-eating disorder who receive CBT do better if they also receive exercise instruction monitored by and subsequently maintained with biweekly booster sessions conducted by exercise staff (77).

Results of medication studies for binge-eating disorder also parallel those for bulimia nervosa. More recent studies, most of them industry funded, have shown several SSRIs to be somewhat effective. In 6-week double-blind placebo-controlled trials, fluoxetine (78) and citalopram (79) have each been shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing binge-eating behavior and promoting weight loss. In another small study, fluvoxamine was not more effective than placebo, although improvement was seen with both (80). In a 12-week randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, the SNRI sibutramine was superior to placebo in reducing binge eating, with differential results evident by the third week (81). Several novel anticonvulsants, including topiramate (82) and zonisamide (83), have also shown promise for binge-eating disorder in recent trials, but about 25% of patients in these studies discontinued the anticonvulsant because of adverse events.

Overall, the available evidence seems to favor psychotherapy alone over medications alone for treatment of binge-eating disorder. In a recent randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, the addition of 60 mg/day of fluoxetine to CBT did not appear to alter rates of remission or produce substantial advantage on dimensional measures of binge eating or psychological distress (84). In some other instances, adding medications to CBT-based psychotherapy has appeared to enhance the effects of CBT on eating behavior or at least on symptoms of depression (85).

Questions and controversies

Questions and controversies abound on the treatment of eating disorders, and many of them may yield to future research. For anorexia nervosa, few controlled trials have been conducted because of substantial difficulties in implementing and sustaining controlled trials with this patient group, and many trials suffer from high dropout rates. Consequently, debates remain on optimal nutritional, pharmacological, and psychotherapeutic strategies. For example, the use of supplemental overnight nasogastric feedings for hospitalized patients who are willing to tolerate this intervention deserves more study (86). Similarly, the use of atypical antipsychotics with or without SSRIs for underweight patients merits further investigation. SSRIs may prove to be particularly important for patients who are unable to access specialty inpatient programs. The use of biphosphonates and other currently experimental interventions using bone growth factors to retard or reverse osteopenia and osteoporosis demands more investigation. The value of incorporating psychotherapeutic elements derived from various schools “transtheoretically,” where different approaches are tailored to different stages of these disorders to yield optimum benefits, is unclear. Although motivational enhancement for unmotivated, resistant patients with eating disorders sounds good in theory, its value has yet to be demonstrated in practice. For younger patients and their families, the so-called Maudsley approach of actively enlisting parents to take charge of their children’s eating is receiving considerable attention, but empirical studies are needed to delineate which patients and under what circumstances this approach is most useful.

For bulimia nervosa, current questions to be addressed concern the best mix and staging of transtheoretical psychotherapy treatment elements in relation to severity and concurrent psychiatric comorbidities, the combination of such treatments with medications and other somatic treatments, and management of the difficult syndromes that remain unresponsive to current treatments.

For binge-eating disorder, treatment of the psychological and behavioral problems in the context of obesity—which itself is still difficult to treat—remains challenging. In particular, questions regarding the potential value and hazards of gastric surgery in treating seriously obese binge eaters are unresolved.

Recommendations from the authors

Clinicians treating patients with eating disorders should be familiar with APA’s current practice guidelines (20) and Guideline Watch updates, the most recent of which was published in February 2005 (87).

Additional guidelines, many of which also address the role of nonpsychiatric practitioners, are also available, such as those from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence in Great Britain (27, 88), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (26), pediatric groups (89, 90), and the American Dietetic Association (91). Interventions have been evaluated in Cochrane reviews (25). The guidelines all point to the importance of early intervention, interdisciplinary treatment, initial refeeding, careful medical monitoring, involving the family in the treatment of younger patients, flexible psychotherapeutic interventions at various points, judicious use of medications, and individualizing treatments on the basis of specific clinical features. All bemoan the fact that limited evidence has resulted in very broadly written guidelines.

Clinicians searching for resources for patients may find suitable consultants and psychotherapists through the Academy for Eating Disorders (www.aedweb.org). Patients and families may be directed to resources through the National Eating Disorders Association (www.nationaleatingdisorders.org) and the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (www.anad.org).

|

Table 1. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa

|

Table 2. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa

|

Table 3. DSM-IV-TR Research Criteria for Binge-Eating Disorder

1 Hoek HW, van HD: Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 34:383–396Crossref, Google Scholar

2 de Zwaan M: Binge eating disorder and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25(suppl 1):S51–S55Google Scholar

3 Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL: Epidemiology of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 34(suppl):S19–S29Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Fear JL, Joyce PR: Eating disorders and antecedent anxiety disorders: a controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 96:101–107Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Anderluh MB, Tchanturia K, Rabe-Hesketh S, Treasure J: Childhood obsessive-compulsive personality traits in adult women with eating disorders: defining a broader eating disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:242–247Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Halmi KA, Sunday SR, Klump KL, Strober M, Leckman JF, Fichter M, Kaplan A, Woodside B, Treasure J, Berrettini WH, Al Shabboat M, Bulik CM, Kaye WH: Obsessions and compulsions in anorexia nervosa subtypes. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 33:308–319Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Kovacs M, Obrosky DS, Sherrill J: Developmental changes in the phenomenology of depression in girls compared to boys from childhood onward. J Affect Disord 2003; 74:33–48Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Ben-Dor DH, Laufer N, Apter A, Frisch A, Weizman A: Heritability, genetics, and association findings in anorexia nervosa. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2002; 39:262–270Google Scholar

9 Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS: Heritability of binge-eating and broadly defined bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:1210–1218Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS: Eating disorders during adolescence and the risk for physical and mental disorders during early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:545–552Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Miller KK, Grinspoon SK, Ciampa J, Hier J, Herzog D, Klibanski A: Medical findings in outpatients with anorexia nervosa. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:561–566Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Halmi KA, Eckert E, Marchi P, Sampugnaro V, Apple R, Cohen J: Comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses in anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:712–718Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Masters K: Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2215–2221Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Bulik CM, Klump KL, Thornton L, Kaplan AS, Devlin B, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Strober M, Woodside DB, Crow S, Mitchell JE, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano GB, Keel PK, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH: Alcohol use disorder comorbidity in eating disorders: a multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1000–1006Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Westen D, Harnden-Fischer J: Personality profiles in eating disorders: rethinking the distinction between axis I and axis II. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:547–562Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Lock J: Treating adolescents with eating disorders in the family context: empirical and theoretical considerations. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2002; 11:331–342Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Eddy KT, Franko D, Charatan DL, Herzog DB: Predictors of mortality in eating disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:179–183Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Nielsen S, Moller-Madsen S, Isager T, Jorgensen J, Pagsberg K, Theander S: Standardized mortality in eating disorders: a quantitative summary of previously published and new evidence. J Psychosom Res 1998; 44(3–4):413–434Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Sullivan PF: Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1073–1074Crossref, Google Scholar

20 American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157(Jan suppl)Google Scholar

21 Vitousek K, Watson S, Wilson GT: Enhancing motivation for change in treatment-resistant eating disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 1998; 18:391–420Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Nova E, Lopez-Vidriero I, Varela P, Toro O, Casas JJ, Marcos AA: Indicators of nutritional status in restricting-type anorexia nervosa patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Clin Nutr 2004; 23:1353–1359Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Ramacciotti CE, Coli E, Biadi O, Dell’Osso L: Silent pericardial effusion in a sample of anorexic patients. Eat Weight Disord 2003; 8:68–71Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Golden NH: Osteopenia and osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa. Adolesc Med 2003; 14:97–108Google Scholar

25 Hay P, Bacaltchuk J, Claudino A, Ben-Tovim D, Yong PY: Individual psychotherapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; 4:CD003909Google Scholar

26 Beumont P, Hay P, Beumont D, Birmingham L, Derham H, Jordan A, Kohn M, McDermott B, Marks P, Mitchell J, Paxton S, Surgenor L, Thornton C, Wakefield A, Weigall S; Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Anorexia Nervosa: Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2004; 38:659–670Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Dix A: Clinical management special: mental health: one to chew over. Health Serv J 2004; 114(5899):28–29Google Scholar

28 Eisler I, Dare C, Hodes M, Russell G, Dodge E, Le Grange D: Family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: the results of a controlled comparison of two family interventions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000; 41:727–736Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Robin AL, Siegel PT, Moye AW, Gilroy M, Dennis AB, Sikand A: A controlled comparison of family versus individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1482–1489Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Wolfe BE, Gimby LB: Caring for the hospitalized patient with an eating disorder. Nurs Clin North Am 2003; 38:75–99Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Watson TL, Bowers WA, Andersen AE: Involuntary treatment of eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1806–1810Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Howard WT, Evans KK, Quintero-Howard CV, Bowers WA, Andersen AE: Predictors of success or failure of transition to day hospital treatment for inpatients with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1697–1702Google Scholar

33 Olmsted MP, Kaplan AS, Rockert W: Relative efficacy of a 4-day versus a 5-day day hospital program. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 34:441–449Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Zipfel S, Reas DL, Thornton C, Olmsted MP, Williamson DA, Gerlinghoff M, Herzog W, Beumont PJ: Day hospitalization programs for eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 2002; 31:105–117Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Attia E, Haiman C, Walsh BT, Flater SR: Does fluoxetine augment the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa? Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:548–551Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Strober M, Pataki C, Freeman R, DeAntonio M: No effect of adjunctive fluoxetine on eating behavior or weight phobia during the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: an historical case-control study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999; 9:195–201Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Barbarich NC, McConaha CW, Gaskill J, La Via M, Frank GK, Achenbach S, Plotnicov KH, Kaye WH: An open trial of olanzapine in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1480–1482Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Powers PS, Santana CA, Bannon YS: Olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: an open label trial. Int J Eat Disord 2002; 32:146–154Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Malina A, Gaskill J, McConaha C, Frank GK, LaVia M, Scholar L, Kaye WH: Olanzapine treatment of anorexia nervosa: a retrospective study. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 33:234–237Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Mondraty N, Birmingham CL, Touyz S, Sundakov V, Chapman L, Beumont P: Randomized controlled trial of olanzapine in the treatment of cognitions in anorexia nervosa. Australasian Psychiatry 2005; 13:72–75Crossref, Google Scholar

41 McIntosh VV, Jordan J, Carter FA, Luty SE, McKenzie JM, Bulik CM, Frampton CM, Joyce PR: Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:741–747Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Lantzouni E, Frank GR, Golden NH, Shenker RI: Reversibility of growth stunting in early onset anorexia nervosa: a prospective study. J Adolesc Health 2002; 31:162–165Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Golden NH, Lanzkowsky L, Schebendach J, Palestro CJ, Jacobson MS, Shenker IR: The effect of estrogen-progestin treatment on bone mineral density in anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2002; 15:135–143Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Grinspoon S, Thomas L, Miller K, Herzog D, Klibanski A: Effects of recombinant human IGF-I and oral contraceptive administration on bone density in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:2883–2891Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Golden NH, Iglesias EA, Jacobson MS, Carey D, Meyer W, Schebendach J, Hertz S, Shenker IR: Alendronate for the treatment of osteopenia in anorexia nervosa: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90:3179–3185Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Kaye WH, Nagata T, Weltzin TE, Hsu LK, Sokol MS, McConaha C, Plotnicov KH, Weise J, Deep D: Double-blind placebo-controlled administration of fluoxetine in restricting- and restricting-purging-type anorexia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:644–652Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Pike KM, Walsh BT, Vitousek K, Wilson GT, Bauer J: Cognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:2046–2049Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Dare C, Eisler I, Russell G, Treasure J, Dodge L: Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: randomised controlled trial of out-patient treatments. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:216–221Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Eisler I, Dare C, Russell GF, Szmukler G, Le Grange D, Dodge E: Family and individual therapy in anorexia nervosa: a 5-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1025–1030Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W: Atypical anorexia nervosa: separation from typical cases in course and outcome in a long-term prospective study. Int J Eat Disord 1999; 25:135–142Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W: The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10–15 years in a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord 1997; 22:339–360Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Bacaltchuk J, Hay P, Trefiglio R: Antidepressants versus psychological treatments and their combination for bulimia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; 4:CD003385Google Scholar

53 Hay PJ, Bacaltchuk J: Psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa and binging. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; 1:CD000562Google Scholar

54 Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ: Eating disorders. Lancet 2003; 361(9355):407–416Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Fairburn CG, Jones R, Peveler RC, Hope RA, O’Connor M: Psychotherapy and bulimia nervosa: longer-term effects of interpersonal psychotherapy, behavior therapy, and cognitive behavior therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:419–428Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Safer DL, Telch CF, Agras WS: Dialectical behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:632–634Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Hsu LK, Rand W, Sullivan S, Liu DW, Mulliken B, McDonagh B, Kaye WH: Cognitive therapy, nutritional therapy and their combination in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 2001; 31:871–879Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Bailer U, de Zwaan M, Leisch F, Strnad A, Lennkh-Wolfsberg C, El-Giamal N, Hornik K, Kasper S: Guided self-help versus cognitive-behavioral group therapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2004; 35:522–537Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Bara-Carril N, Williams CJ, Pombo-Carril MG, Reid Y, Murray K, Aubin S, Harkin PJ, Treasure J, Schmidt U: A preliminary investigation into the feasibility and efficacy of a CD-ROM-based cognitive-behavioral self-help intervention for bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2004; 35:538–548Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Pritchard BJ, Bergin JL, Wade TD: A case series evaluation of guided self-help for bulimia nervosa using a cognitive manual. Int J Eat Disord 2004; 36:144–156Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Ghaderi A, Scott B: Pure and guided self-help for full and sub-threshold bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Br J Clin Psychol 2003; 42(pt 3):257–269Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Durand MA, King M: Specialist treatment versus self-help for bulimia nervosa: a randomised controlled trial in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2003; 53(490):371–377Google Scholar

63 Carter JC, Olmsted MP, Kaplan AS, McCabe RE, Mills JS, Aime A: Self-help for bulimia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:973–978Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Mickley D, Sysko R, Parides MK: Treatment of bulimia nervosa in a primary care setting. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:556–561Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Mitchell JE, Fletcher L, Hanson K, Mussell MP, Seim H, Crosby R, Al-Banna M: The relative efficacy of fluoxetine and manual-based self-help in the treatment of outpatients with bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:298–304Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Walsh BT, Agras WS, Devlin MJ, Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, Kahn C, Chally MK: Fluoxetine for bulimia nervosa following poor response to psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1332–1334Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Mitchell JE, Halmi K, Wilson GT, Agras WS, Kraemer H, Crow S: A randomized secondary treatment study of women with bulimia nervosa who fail to respond to CBT. Int J Eat Disord 2002; 32:271–281Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Mitchell JE, Agras WS, Wilson GT, Halmi K, Kraemer H, Crow S: A trial of a relapse prevention strategy in women with bulimia nervosa who respond to cognitive-behavior therapy. Int J Eat Disord 2004; 35:549–555Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Fluoxetine in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:139–147Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Gelber D, Levine J, Belmaker RH: Effect of inositol on bulimia nervosa and binge eating. Int J Eat Disord 2001; 29:345–348Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Faris PL, Kim SW, Meller WH, Goodale RL, Oakman SA, Hofbauer RD, Marshall AM, Daughters RS, Banerjee-Stevens D, Eckert ED, Hartman BK: Effect of decreasing afferent vagal activity with ondansetron on symptoms of bulimia nervosa: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2000; 355(9206):792–797Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Hedges DW, Reimherr FW, Hoopes SP, Rosenthal NR, Kamin M, Karim R, Capece JA: Treatment of bulimia nervosa with topiramate in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, part 2: improvement in psychiatric measures. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1449–1454Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Hoopes SP, Reimherr FW, Hedges DW, Rosenthal NR, Kamin M, Karim R, Capece JA, Karvois D: Treatment of bulimia nervosa with topiramate in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, part 1: improvement in binge and purge measures. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1335–1341Crossref, Google Scholar

74 El-Giamal N, de Zwaan M, Bailer U, Lennkh C, Schussler P, Strnad A, Kasper S: Reboxetine in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: a report of seven cases. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 15:351–356Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Fassino S, Daga GA, Boggio S, Garzaro L, Piero A: Use of reboxetine in bulimia nervosa: a pilot study. J Psychopharmacol 2004; 18:423–428Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell EB, Cohen LR, Saelens BE, Dounchis JZ, Frank MA, Wiseman CV, Matt GE: A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:713–721Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Pendleton VR, Goodrick GK, Poston WS, Reeves RS, Foreyt JP: Exercise augments the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of binge eating. Int J Eat Disord 2002; 31:172–184Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Arnold LM, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Welge JA, Bennett AJ, Keck PE: A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:1028–1033Crossref, Google Scholar

79 McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Malhotra S, Welge JA, Nelson EB, Keck PE Jr.: Citalopram in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:807–813Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Pearlstein T, Spurell E, Hohlstein LA, Gurney V, Read J, Fuchs C, Keller MB: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluvoxamine in binge eating disorder: a high placebo response. Arch Women Ment Health 2003; 6:147–151Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Appolinario JC, Bacaltchuk J, Sichieri R, Claudino AM, Godoy-Matos A, Morgan C, Zanella MT, Coutinho W: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sibutramine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:1109–1116Crossref, Google Scholar

82 McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, Keck PE Jr, Rosenthal NR, Karim MR, Kamin M, Hudson JI: Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:255–261Crossref, Google Scholar

83 McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Hudson JI, Nelson EB, Keck PE: Zonisamide in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: an open-label, prospective trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:50–56Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT: Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:301–309Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, Moretti S, Di Bernardo M, Bertelli M, Rotella CM, Faravelli C: Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine combined with individual cognitive-behaviour therapy in binge eating disorder: a one-year follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom 2001; 70:298–306Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Robb AS, Silber TJ, Orrell-Valente JK, Valadez-Meltzer A, Ellis N, Dadson MJ, Chatoor I: Supplemental nocturnal nasogastric refeeding for better short-term outcome in hospitalized adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1347–1353Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Yager J, Devlin MJ, Halmi KA, Herzog DB, Mitchell JE, Powers PS, Zerbe KJ: Guideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, 2nd edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2005; available online at http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/reatg/pg/prac_guide.cfm.Google Scholar

88 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: Eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and related eating disorders. (Clinical Guideline 9). London, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, January 2004; available online at www.nice.org.uk/CG009NICEguidelineGoogle Scholar

89 Ebeling H, Tapanainen P, Joutsenoja A, Koskinen M, Morin-Papunen L, Jarvi L, Hassinen R, Keski-Rahkonen A, Rissanen A, Wahlbeck K; Finnish Medical Society Duodecim: A practice guideline for treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Ann Med 2003; 35:488–501Crossref, Google Scholar

90 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence: Identifying and treating eating disorders. Pediatrics 2003; 111:204–211Crossref, Google Scholar

91 American Dietetic Association: Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition intervention in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS). J Am Diet Assoc 2001; 101:810–819Crossref, Google Scholar