Interpersonal Maneuvers of Manic Patients

Abstract

Manic patients, excited schizoaffective patients, and agitated schizophrenic patients were rated using a “manic interpersonal interaction scale” that evaluated a number of interpersonal interactions including testing of limits, projection of responsibility, sensitivity to others’ soft spots, attempts to divide staff, flattering behavior, and ability to evoke anger. Manic patients showed an elevation in each of these items; overall, elevations were greater than those of schizoaffective and schizophrenic patients. The intensity of the manic state also correlated with the degree of elevation of the manic interpersonal interaction scale scores.

Recent pharmacological advances and increased understanding of the nature of affective disorders has led to an intensified interest in the diagnosis, biochemistry, and treatment of mania (1, 2). Recent publications have dealt with the nature of those symptoms characteristic of mania, and Beigel and Murphy have recently devised a manic rating scale based on a number of items thought to be characteristic of mania (3). Their work shows that those items indicating most precisely the severity of mania are representative of the “classic signs” of mania, including manifestations of increased motor activity, increased verbal productions, increased rapidity of thought processes, anger, poor judgment, and increased social contact. In addition, the acutely manic patient appears to have the ability to create interpersonal havoc with his family and therapists, and thus is one of the most challenging, taxing, and difficult of patients (4).

On the basis of clinical observations, a number of interpersonal maneuvers and characteristics have been described that appear to be present in the acutely manic state and that involve “patient-other” interactions, rather than “patient-centered” symptoms (4). Manic patients frequently manipulate the self-esteem of others, either building up or denigrating a person’s sense of pride. They show a remarkable perceptiveness to areas of vulnerability and conflict in others and possess a keen ability to sense, reveal, and exploit areas of covert sensitivity. They often project responsibility onto others, shifting responsibility in such a way that others become responsible for their actions. Furthermore, they engage in progressive limit testing and in so doing subtly extend externally imposed limits.

These “interpersonal-interactional” characteristics have not previously been subjected to quantitative evaluation. No objective correlations have been made between the extent of a manic patient’s characteristic interpersonal interactions and the more classic symptoms of mania. Nevertheless, we have observed clinically that a manic’s interpersonal interactions seem to be associated with such classic symptoms of mania as flight of ideas, insomnia, hyperactivity, grandiosity, denial of illness, high energy level, irritability, lability of affect, manipulativeness, logorrhea, and assaultive behavior. Such a relationship is of theoretical importance, since it links a character style to the fluctuations in a psychosis.

Our hypothesis, then, is that the manic disorder is more pervasive than is thought and does more than merely cause specific symptoms. We postulate that it causes an alteration in life-style and interpersonal relationships that is linked to the intensity of the manic person’s psychopathology. Evidence in support of this hypothesis would be provided by data showing that specific interactional characteristics occur selectively in those patients with manic symptoms but not in nonmanic patients, and that when the manic episode remits, the interactional characteristics also remit. The purpose of this study is to quantitatively investigate whether the various types of manic interpersonal interactions described above are linked to specific commonly accepted symptoms and to note whether the manic interpersonal interactions outlined above are found selectively in manic patients as compared to schizoaffective and schizophrenic patients.

Method

The investigation was carried out on the 11-bed inpatient research ward of the Tennessee Neuropsychiatric Institute. A total of 29 patients were included in the study. Patients included acutely ill activated schizophrenics; schizoaffective patients, excited type; and manic-depressive patients, manic type. (All of the patients in the “activated schizophrenic” group suffered from schizophrenia as defined in the APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-II]. They included patients with schizophrenia, paranoid type; those with an acute schizophrenic episode; and those with schizophrenia, chronic undifferentiated type. All patients showed obvious and florid symptoms, including hallucinations, delusions, and bizarre behavior. They interacted frequently with staff and fellow patients. They were considered “activated” in the sense that they did not mask their symptoms with emotional withdrawal.) Diagnosis was established on the basis of the consensus of three experienced psychiatrists, nurses’ notes, family history, psychiatric history, and response to lithium and/or phenothiazines. Ultimately a diagnosis was based on the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II). Also, all patients were assigned a score (“continuum score”) between zero and 15, which represented a continuum between schizophrenia and mania. A score of zero was assigned to patients showing only schizophrenic symptoms and 15 to patients with symptoms of mania alone. Intermediate scores were assigned to patients with both manic and schizophrenic symptoms. The number given to a patient on the schizophrenic-to-manic continuum was determined by the average of the numbers assigned by three psychiatrists. More than one patient could be assigned a given “continuum score.” For purposes of data analysis, patients with an average continuum score of zero to five were defined as schizophrenic, patients with an average of six to ten were considered to be schizoaffective, and patients with a score of 11 to 15 were considered to be manic. Nine patients were assigned scores between zero and five (schizophrenic), ten patients received scores between six and ten (schizoaffective), and ten patients received scores between 11 and 15 (manic). The patient group consisted of 17 women and 12 men.

Each patient was rated twice daily while acutely ill on a scale from zero to 15 on a number of interactional variables by the consensus of a team of nurse raters. A score of zero to five equaled mild symptoms, six to ten equaled moderate symptoms, and 11 to 15 equaled severe symptoms. The nurses rated each patient on a continuum as to testing of limits, projection of responsibility, sensitivity to others’ soft spots, attempts to divide staff, flattering behavior, and ability to evoke anger in people. The sum of scores of the six items evaluated on a given day for a given patient was obtained to create a “manic interpersonal interaction scale” score (MIIS). For purposes of data analysis, an average of the daily scores for the individual items and for their sum (MIIS) for a given patient were obtained over the time the patient was acutely ill. No less than five consecutive daily ratings were averaged in any patient. The data obtained when a patient had attained remission was handled similarly. The definition of each of these items has been described previously (4). Each patient was also evaluated daily using a 15-point global mania rating scale derived from the Bunney-Hamburg scale (5).

A total of five manic patients were rated longitudinally on a daily basis both while they were acutely ill and after remission had occurred to determine whether the interactional symptoms decreased with clinical improvements and/or with a decrease in the global mania ratings. Thus the relationship of the manic interpersonal interaction scale scores to diagnostic category and severity of global mania symptoms was evaluated.

Results

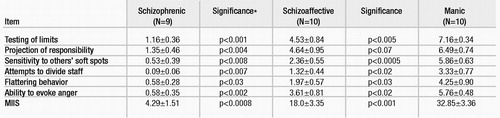

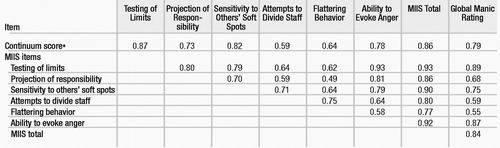

The data were analyzed to determine whether diagnosis correlated with the manic interpersonal interaction scale score. Table 1 demonstrates these relationships for the MIIS score and for the six individual items evaluated. Analysis of the data revealed that manic patients obtained a statistically significantly higher average MIIS score than the schizoaffective patients (32.85±3.36 vs. 18.01±3.35, p<0.001). Schizoaffective patients obtained a higher score than activated schizophrenics (18.01±3.35 vs. 4.29±1.51, p<0.0008). In addition, the manic patients showed an elevation in each of the individual items rated (testing of limits, projection of responsibility, sensitivity to others’ soft spots, attempts to divide staff, flattering behavior, and ability to evoke anger). Their scores were higher than those of the schizoaffective group, and the schizoaffective group’s were higher than the schizophrenic group’s. Table 2 demonstrates that in the subject group, a high degree of intercorrelation existed between each of the six individual items, the global mania rating, the continuum score, and the MIIS score. For example, a high positive correlation (r=0.86) existed between the MIIS score of a given patient while he was acutely ill and the patient’s continuum score (the place on the continuum between schizophrenia and mania assigned the patient). Furthermore, a high positive correlation existed between a patient’s global mania rating (Bunney-Hamburg scale score) and the MIIS score (r=0.84).

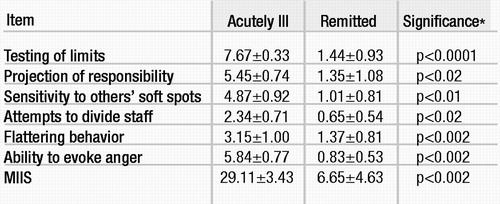

In addition, for those five manic patients evaluated longitudinally while acutely ill and again following remission, table 3 demonstrates that the MIIS score and the six individual item scores diminished dramatically as remission occurred (acutely ill MIIS score=29.11±3.43, remitted MIIS score=6.65±4.63, p<0.002). The individual items and the MIIS score decreased significantly as a patient’s global mania rating decreased, whether such a decrease in global mania rating occurred spontaneously or following pharmacotherapy.

The following case is illustrative: A 51-year-old manic-depressive patient was admitted to the unit. She exhibited characteristic symptoms of mania including irritability, overtalkativeness, flight of ideas, elation, grandiosity, and insomnia. Her premorbid history was characteristic of a manic-depressive patient in that she had been a high-achieving, rather competitive mother and wife who had shown no intellectual or personality deterioration over the years. On admission, the patient commented that even though the unit was supposed to be a “therapeutic community,” the staff was not being honest because they were not eating lunch with the patients. She also frequently commented that she wished to speak only to the chief of the ward, stating that subordinate doctors and the resident “couldn’t understand me as well.” She constantly attempted to exceed her limit of three phone calls per week, saying that the chief of the unit had given her permission to do so. Her request for phone calls always appeared reasonable. It was not until clarification the unit chief by the rather irritated nursing staff occurred that it was realized that he had stated only that at some time in the future she could make more phone calls. Furthermore, although she always remembered the name of the chief of the unit, she “forgot” or confused the names of other doctors, social workers, and aides and used their names interchangeably, thereby allowing an accentuation of suppressed conflicts in the “therapeutic community.” The patient was alternately flattering and critical of staff members. A number of the members of the patient group and the staff were angry with the patient, feeling antagonized by her manipulative behavior, her incessant demands, and her frequent testing of limits. The above interactions and the anger of the staff and patients decreased dramatically as the patient’s condition improved following the institution of lithium carbonate therapy.

Discussion

The data indicate that patients manifesting the typical symptoms of mania as measured by a standardized rating scale (the Bunney-Hamburg scale) also show certain interpersonal characteristics that are predictable and that appear to correlate in intensity with the severity of the manic state as defined by the intensity of such symptoms as flight of ideas, cheerfulness, and talkativeness. These interpersonal characteristics appear to be at least as representative of the manic state as the more “classic” symptoms of mania. They exist only infrequently in activated schizophrenics and are less frequent in excited schizoaffectives than in manic patients.

In our work with manic patients, we have been struck with the degree to which these patients engage in the interpersonal maneuvers described above. Initially, we thought that this character style was generally typical of the manic patient, occurring during the manic episode, during periods of normothymia, and during depressive episodes. With continued observation, however, it became apparent to us that the various types of manic interpersonal behavior disappeared when the manic episode remitted, either spontaneously or following lithium therapy. It would seem that this behavior, rather than being characteristic of a premorbid personality style that merely continues into a period of illness, is a characteristic of the manic episode, much as short-term symptom changes such as flight of ideas, overtalkativeness, and grandiosity are characteristic of acute mania. It is noteworthy that historically some of the typical symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations, delusions, and posturing, were described first, followed later by descriptions of the schizophrenic thought disorder and by descriptions of the schizophrenic’s characteristic shyness, aloofness, and interpersonal emotional withdrawal. It is our hypothesis that a manic episode is characterized not only by certain symptoms, such as flight of ideas, grandiosity, etc., but also, as with the schizophrenic, by a certain style of relating interpersonally. What may be unique in the acutely manic patient is the fact that he appears to have changes in his style of interpersonal interactions that fluctuate dramatically with the phases of the manic illness. This may be theoretically important, since styles of interpersonal relating are usually thought to be long-term and continuing characteristics of behavior, in contrast to symptoms, which can fluctuate over brief intervals. Thus, our observations suggest that the acute manic disorder has a widespread effect on personality, affecting not only drive and subsequent defenses but also those aspects of ego structure that govern an individual’s personality style.

Obviously, patients with other personality types and diagnostic labels may have some of the same interpersonal characteristics that the manic patient has. However, the specific interpersonal maneuvers we have mentioned, when found in an acutely ill psychotic patient, would seem to suggest a diagnosis of mania rather than schizophrenia. Such diagnostic differentiation between schizophrenic and manic patients is of therapeutic importance, since lithium carbonate appears to be relatively more effective in manics. Furthermore, both manic and schizophrenic patients can show hallucinations, delusions, and persecutory, grandiose, and paranoid ideas. Also, on occasion it may be difficult to distinguish differences between flight of ideas and loose associations. In such a situation, we have found that interpersonal characteristics are useful in differentiating among mania, schizoaffective disease, and schizophrenia.

The definition and acknowledgment of the interpersonal maneuvers of manic patients have a number of therapeutic implications. Generally, we have found that manic patients, while acutely manic, have a unique ability to intensify staff dissension as well as intrapersonal conflict and, in the ensuing chaos, to create a situation in which the psychotherapeutic or milieu treatment is undermined or abolished. The acutely manic patient is a master at exploiting covert conflicts in a ward staff and making suppressed feelings and anxieties overt. Also, in an almost uncanny way, the manic patient, by appealing to an individual’s sense of self-esteem, can divide and conquer staff members. In part, the manic patient’s success in manipulating lies in his ability to seem plausible and reasonable, thus undercutting a therapist’s ability to define his behavior as “sick” and to assume a “helping” role.

Although we offer no therapeutic panacea, we have found that a logical system of conceptualizing manic interpersonal activity, as described above, has been useful in providing us a framework for interpreting and reacting to the manic patient’s style of relating. Specifically, daily use of the MIIS scale has been therapeutic in that it has caused the staff of our inpatient milieu therapy unit to be forced to continuously evaluate the interpersonal activity of the manic patients admitted to the unit and at least occasionally to accept such maneuvers with good humor, as “part of the game.” Thus, expecting the manic patient to divide staff members, assault self-esteem, progressively test limits, project responsibility, and distance himself from family members allows anticipation of these activities, with the possibility of formulating concrete responses and plans. This in turn decreases staff anger. Formal evaluation of manic interpersonal behavior allows those in therapeutic positions to consider their own roles in interacting with manics. How they may unwittingly allow the manic patient to manipulate self-esteem or how they may become defensive when he attacks their self-image can be a subject of consideration.

We feel it is important to acknowledge conflicts when one is dealing with manic patients, thus deflating their tendency to manipulate and exploit covert conflicts. Frequent staff meetings centering around manic interactions may undercut the ability of the manic patient to divide, for it is in the context of faulty communication that he is most effective. It may be useful to view the manic patient’s ability to perceive covert conflict as a positive attribute, to be used as a diagnostic tool to unearth and externalize interpersonal dissension within a staff.

It is worthwhile to focus on the feelings, realities, and affects that underlie manic patients’ behavior, rather than to become caught up in a characteristic battle of semantics. When a therapist agrees to engage with the patient in semantic quibbling, he has thereby abdicated his objective usefulness to the patient by allowing a shift of focus to an arena in which the manic patient will be successful in avoiding therapeutic work, and, in fact, may show superior abilities.

Finally, we have found that the unambivalent, firm, and rather arbitrary setting of limits and controls is most useful in decreasing manic symptomatology. It seems that when the manic is unable to successfully divide staff members, exploit areas of conflict and vulnerability, and exceed set limits, his manipulative and uncontrolled behavior decreases. It may be that the psychotic manic patient hears most easily the nonverbal communication implicit in the setting of limits—the statement that the patient is indeed controllable and that the therapist cares enough and is powerful enough to protect him from his self-destructive activities.

Discussion

Harold W. Arlen, M.D. (Los Angeles, Calif.)—The task of quantifying interpersonal modes of relating is even more prone to subjective distortion and failure of scientific replicability than is the comparatively simpler but still very difficult problem of assessing discrete neurotic or psychotic symptomatology. The use of hospital ward personnel as the clinical assessors, with the wide diversity of clinical sophistication that this heterogeneous grouping characteristically entails, is but another potential pitfall in any attempt to create a scientifically sterile field in which to engage in meaningful research that requires exactitude, standardization, and quantification. Less courageous investigators might well have been daunted by such formidable obstacles, and it is to the considerable credit of the authors that they persevered and set up a research design that approaches a degree of scientific control that is still comparatively rare in clinical psychiatry.

It is not a heady undertaking to take potshots at potentially weak links in the research methodology: 1) the size of the patient population (29 patients, of whom ten were judged to be manic-depressive), 2) the use of nursing staff raters, and 3) the separation of the 29 patients into the three diagnostic categories—activated schizophrenics, schizoaffective patients, excited type, and manic-depressive patients, manic type—by the consensus of three experienced psychiatrists using the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II). Surely one could question the degree to which the logical fallacy of petitio principii is encroached upon by the methodological use of the very nosology that is being researched. But as Disraeli said, “It is much easier to be critical than to be correct,” and as a clinician, I would agree that it would avail us more to consider the practical consequences of the authors’ contribution.

Indeed, the specificity of the use of lithium in the treatment of many manic states makes the recognition of this group of disorders, in contradistinction to the schizophrenic group, a crucial one. The authors state their hypothesis as follows: “The manic disorder is more pervasive than is thought and does more than merely cause specific symptoms. We postulate that it causes an alteration in life-style and interpersonal relationships that is linked to the intensity of the manic person’s psychopathology.” This is, to be sure, a very modest hypothesis when one considers that a thorough study of any psychopathological process would reveal it to be more pervasive than a mere cause of specific symptoms. This is certainly true for the schizophrenias, as the authors themselves acknowledge, and it is equally true for the gamut of psychoneurotic and characterological disturbances that are listed in the diagnostic manual. The authors state that “what may be unique in the acutely manic patient is the fact that he appears to have changes in his style of interactions that fluctuate dramatically with the phases of the psychotic illness. This may be theoretically important, since styles of interpersonal relating are usually thought to be long-term and continuing characteristics of behavior, in contrast to symptoms, which can fluctuate over brief intervals.” Again, I would question whether the dramatic fluctuations of the interpersonal interactions of the manic patient with the phases of his psychotic illness are unique for this group of patients any more than they are for a schizophrenic. With the advent of ego psychology in the 1920s, it has become commonplace to deal with psychopathological phenomena both in terms of their discernible symptomatology and the interpersonal characteristics and relationships that they give rise to. The authors have not demonstrated, despite their assertion, that the interpersonal fluctuations of the manic are more dramatic than those of the schizophrenic. But even if they had demonstrated this hypothesis adequately, it does not justify as a conclusion their very next assertion: “Thus, our observations suggest that the acute manic disorder has a widespread effect on personality, affecting not only drive and subsequent defenses, but also those aspects of ego structure that govern an individual’s personality style.” This conclusion is also true for the schizophrenic and other diagnostic entities.

The unfolding of the still incomplete catecholamine hypothesis is appealing in its attempt to offer a scientifically parsimonious rationale for the biochemistry of the affective disorders. That a significant percentage of manic patients fail to respond to lithium therapy would seem to suggest that there is more than a single biochemical pathway that has gone awry. It is difficult to avoid the temptation to assign a statistically useful diagnostic label to a complex of related but different disease processes. Unless we yield to this temptation, research studies such as the one under discussion are often not possible.

And finally we come to what perhaps is the most important difficulty. The Bunney-Hamburg study cited in the authors’ list of references revealed that rater agreement decreased as the intensity of observed behavior increased. What clinician has not had the experience of discovering that the more he knows about any given patient, the more uncertain he is in relegating him to any diagnostic pigeonhole? And how infinitely more complex it is to agree on quantification of interpersonal relationships that are so much more ephemeral and elusive than the symptoms into which they crystallize, not to mention the nosological abstractions that we assign to the symptom complexes. It is when we consider this mind-boggling complexity that we can best turn to the authors with both tolerance and respect for their courageous efforts.

While I do not regard the authors’ hypothesis (that a manic episode is characterized not only by certain symptoms, such as flight of ideas, grandiosity, hyperactivity, logorrhea, lability of affect, etc., but also by a certain style of relating interpersonally such as testing of limits, projection of responsibility, sensitivity to others’ soft spots, attempts to divide staff, flattering behavior, and ability to evoke anger) as more than good perceptive clinical observation, I do feel that the primary clinical value of their contribution is their concluding emphasis on the desirability of conceptualizing the interpersonal modes of behavior of this group of patients in order to coordinate the therapeutic efforts of the milieu team. Clinical research is most productive when it can lead to specific therapeutic modifications, and in this regard the authors have performed a valuable service.

|

Table 1. Average Individual Item Scores and Total Manic Interpersonal Interaction Scale Scores

|

Table 2. Intercorrelations Among Continuum Score, Individual Item and Total MIIS Scores, and Global Mania Rating for 29 Patients

|

Table 3. Average Individual Item Scores and Total Manic Interpersonal Interaction Scale Scores in Five Manic Patients Before and After Clinical Remission

1 Davis JM: Theories of biological etiology of affective disorders. Int Rev Neurobiol 12:145–175, 1970Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Schildkraut JJ: The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 122:509–522, 1965Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Beigel A, Murphy DL: Assessing clinical characteristics of the manic state. Am J Psychiatry 128:688–694, 1971Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Janowsky DS, Leff M, Epstein RS: Playing the manic game. Arch Gen Psychiatry 22:252–261, 1970Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Bunney WE, Hamburg DA: Methods for reliable longitudinal observations of behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 9:114–128, 1963Crossref, Google Scholar