Mindfulness and Psychotherapy

Abstract

Mindfulness is a natural human mental state of moment-to-moment awareness of present experience. It is a skill that can be trained using meditation techniques that sustain focus on the present moment with a nonjudgmental attitude. Mindfulness training has been shown to be effective in relieving the suffering of numerous medical and psychological conditions while enhancing well-being. In particular, affective disorders including anxiety, depression, and personality disorders are particularly well suited to demonstrate benefit to patients when integrating mindfulness meditation techniques with usual psychotherapies, primarily cognitive behavior therapies. In addition, early evidence shows that when the clinician is practicing mindfulness, there is a positive impact on the outcome of the therapy. Mindfulness-based therapeutic interventions are an important technique for clinicians to be aware of in the treatment of their patients' distress. Further study using larger sample sizes and more controlled conditions is warranted to establish the benefit and efficacy of mindfulness-based psychotherapies.

DEFINITION

The practice of mindfulness training for therapeutic purposes has been defined by Kabat-Zinn and Epstein's work over the last two decades. Mindfulness is defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (1–4). Mindfulness is a human mental function that enhances clarity of thought and a more heart-felt engagement with life (1). The goal of mindfulness is “maintaining awareness moment by moment, disengaging oneself from strong attachment to beliefs, thoughts, or emotions, thereby developing a greater sense of emotional balance and well-being” (1). Epstein (2) defines the goal of therapeutic mindfulness as the abilities for “compassionate informed action in the world, to use a wide array of data, make correct decisions, understand the patient and relieve suffering.” Hence, for the clinician, it is the practice of cultivating nonjudgmental awareness in day-to-day life as a practical tool for self-awareness and self-reflection. This skill builds up a latency of reactivity that allows for different decisions and options to be entertained before taking the characteristic or patterned response that has been dysfunctional for our patients or has served the unconscious bias in the practitioner. When established as part of a focused treatment, the usual cognitive behavior techniques seem to be enhanced in efficacy for the patient's condition (5). Because mindfulness techniques foster individual acceptance and responsibility, the patient may feel more empowered in the pursuit of health and healing of a variety of chronic medical and psychiatric conditions. The ability to take charge of the desired change in one's life is enhanced by regular cultivation of mindfulness. One could even say that the wellness, recovery, and prevention movements initiated several decades ago are manifesting in our health care delivery system today as the increased interest and use of mindfulness training.

MINDFULNESS-BASED PSYCHOTHERAPIES

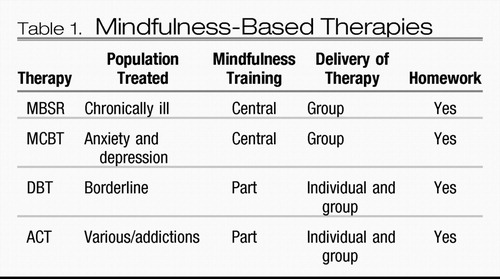

Over the past several decades, mindfulness meditation training has been integrated into cognitive behavior therapy, leading to new treatments with multiple components (Table 1). These components include mindfulness meditation practices, skills training, and relaxation techniques. Kabat-Zinn's mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs (6) and Linehan's dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) (7–9) have led the way for numerous approaches and techniques that integrate mindfulness in therapy. MBSR has been shown to decrease pain and facilitate recovery for numerous medical and psychiatric conditions (1, 3, 5, 10). DBT is an efficacious treatment for borderline personality disorder. Mindfulness meditation is one of the core elements in DBT, which integrates mindfulness and skills training (interpersonal effectiveness, emotional regulation, and distress tolerance) in a comprehensive treatment approach for borderline pathology (8). The ability to gain some perspective through mindfulness training underpins the development of the other self-modulating skills by the individual. Teasdale and others developed a mindfulness-based cognitive behavior therapy (MCBT) for the treatment and prevention of relapse in major depression (11, 12). They found that for patients who had more than three relapses of major depression, the use of MCBT significantly reduced further relapse compared with a control group. With positive experience using mindfulness in DBT for borderline personality disorder and the clear benefits using mindfulness techniques as part of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for depression and the prevention of relapse of depression, there has been a growing use of mindfulness as part of the treatment for many medical and psychiatric conditions. Stephen Hayes (13) developed a branch of CBT called acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). This therapy uses a mindfulness approach to experience “what is” rather than trying to deny or change the painful experience that brings the patient to treatment. However, desired change is brought about through an acceptance and tolerance of the offensive reality in the service of reframing, integrating, and developing from the distress.

|

Table 1. Mindfulness-Based Therapies

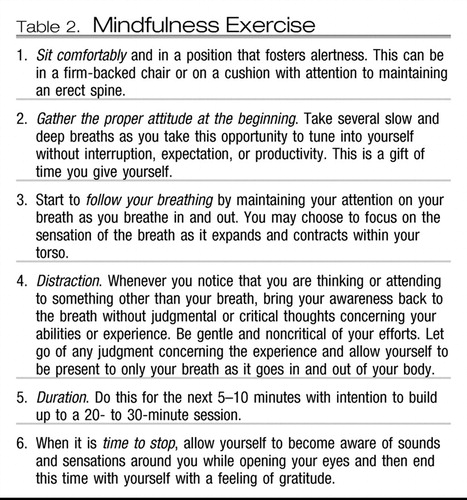

All of these techniques use manuals, are generally time-limited, and use mindfulness meditation training for therapeutic purposes. During active treatment, these therapies incorporate other techniques such as self-reflection, journal writing, skills training, affect tolerance, reframing, and acceptance of “what is” without judgment. The core component in all these treatments is learning mindfulness meditation skills. Various exercises are used to teach patients the skill of focusing their attention on the breath, parts of the body, emotions, and thoughts to enhance the holistic experience of the present moment. Patients are taught to maintain their focus on the object of attention moment by moment; when emotions, sensations, or thoughts arise, they are instructed to practice nonjudgmental observation while bringing their awareness back to the present moment by refocusing on the object of attention (Table 2). As training progresses, the ability to generalize these mindfulness skills becomes a part of daily life and not just limited to the meditation session. This practice allows individuals to observe their thoughts and feelings as changing, nonpermanent, and within a larger context. The mental training to accept the flow of experience using present moment attention builds an ability to delay reactivity, which allows the patient to choose a different behavior that may be better adaptive. This dialectic of the acceptance of “what is” and the desire for behavioral change runs through all of the mindfulness-based therapies. This mental flexibility to accept “what is” in the present moment is the beginning of therapeutic efficacy (14–16).

|

Table 2. Mindfulness Exercise

APPLICATIONS OF MINDFULNESS

Numerous articles have been written about the use and effectiveness of incorporating mindfulness-based therapies in treatment of both medical and psychiatric conditions. Two recently published books provide extensive bibliographies and synthesis of much of the literature that shows the effectiveness of these techniques (17, 18). In the initial studies using MBSR in the treatment of anxiety and panic, there was significant symptom improvement, which persisted in a follow-up study 3 years later (6). This study did not have a control component but was an indication in the early phase of the scientific exploration of MBSR that there was substantial benefit when mindfulness meditation techniques were incorporated in treatment. Recent studies show the efficacy of mindfulness meditation incorporated into therapies for pain (19), various cancers (20, 21), HIV (22), cardiovascular disease (23, 24), perinatal mood and stress (25), premenstrual syndrome (26), insomnia (27), anxiety (28), depression and treatment-resistant depression (29–31), suicidal ideation (32, 33), and borderline personality pathology (9). Weiss et al. (10) found that when patients with anxiety and depressive symptoms were treated with psychotherapy plus MBSR training, they made psychological improvement similar to that of a control group receiving just psychotherapy. However, the MBSR-trained patients showed greater gains in measures of goal attainment and were able to terminate therapy sooner than control subjects and demonstrated lasting improvement and satisfaction at a 6-month follow-up. Kingston et al. (29) randomly assigned 19 patients with residual depressive symptoms to either a MCBT group or a treatment as usual group. They found significant reduction in the depressive symptoms and even more symptom reduction at a 1-month follow-up compared with control subjects. Hepburn et al. (33) randomly assigned 68 patients with depression and suicidal thinking to an MCBT group or waitlist control group and then followed Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores and a measure of thought suppression. The MCBT group improved their BDI scores and demonstrated diminished thought suppression compared with the control group. Thought suppression was correlated with obsessive preoccupation with suicidal thinking. Less thought suppression meant less suicidal thinking. All of the studies mentioned above had small sample sizes, and most of these studies used control subjects to demonstrate significant improvement of the condition studied.

BIOLOGICAL BASIS OF MINDFULNESS

Neuroscience findings of neuronal changes during meditation are varied and may relate to the specific type of meditation technique that subjects practice (34). For instance, Lazar et al. (35) compared the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of five people during Kundalini meditation with those of control subjects. Their data reflected activation of frontal and parietal cortex (attentional networks) and cingulate, amygdala, midbrain, and hypothalamus (arousal and autonomic networks) compared with those of control subjects. Davidson et al. (36) used fMRI and other biomarkers to study MBSR practitioners compared with control subjects and demonstrated activation of the left prefrontal cortex (increased attention) and diminution of amygdala activity (less emotional arousal) during mindfulness meditation, implying an increase of positivity and sense of well-being and less emotional reactivity. The difference between a more activating meditation technique such as Kundalini and the calming focus technique of mindfulness meditation may be reflected in the different brain changes noted when these distinct meditation techniques (e.g., activated amygdala for Kundalini and diminished activity of the amygdala for mindfulness meditation) are studied. Such a brain state pattern activated by a mindfulness meditation practice may be the common mechanism (enhanced attention skills with less emotional reactivity associated with the focus of attention) that facilitates improvement for many different conditions (14, 37).

THERAPISTS WHO PRACTICE MINDFULNESS

The use of MBSR programs for health care professionals to counteract the stress inherent in health care settings has been studied owing to the impairment experienced by stressed professionals in the form of depression, job dissatisfaction, and emotional distress (38). A randomized control pilot study by Shapiro et al. (38) demonstrated that after an 8-week MBSR intervention, the mindfulness-trained professionals showed reduced stress and increased quality of life and self-compassion. Recently, Epstein's group at the University of Rochester, which studies medical education and professionalism, published a study in the annual medical education issue of JAMA about a mindfulness-based program for primary care physicians. They showed that physicians experiencing burnout who participated in a continuing medical education program based on mindful communication (mindfulness meditation, narrative medicine, and appreciative inquiry) had improvements in measurements of personal well-being and increased empathy and compassion for patients (39). The curriculum used mindfulness meditation training along with writing about personal and professional challenging experiences (narrative medicine) and exploring how these experiences were successfully resolved and what personal qualities were used for success (appreciative inquiry). Significantly, this study showed increased empathy, resilience, and professional efficacy as well as decreases in stress, emotional distress and reactivity to stress (39). These changes endured for 3 months after the program ended, and the research group plans further follow-up of the cohort. This study provides evidence to support the development of continuing medical education programs using a mindfulness meditation component for the treatment and prevention of physician burnout (39).

Over the past decade, Williams, a research psychologist, has been conducting psychotherapy research and discussed her findings concerning therapist self-awareness in an early career award article published in 2007 (40). The awareness of positive or negative thoughts in the therapist during therapy sessions affected the therapist's experience of the efficacy of any particular treatment session. She found that when therapists are more self-aware about either their positive or negative inner state during therapy sessions, both the therapist and patient experienced the session as helpful. Her conclusions call for further research of this process of the therapist's mindful presence in the “healing power of the psychotherapy relationship” (40).

In addition to the benefit the therapist may have using mindfulness practices, there is growing evidence that the therapist who practices mindfulness meditation may have a positive impact on the outcome of treatment for the patient. Grepmair et al. (41) studied the effect on treatment outcome when psychotherapists in training practiced mindfulness meditation. This German study of postbaccalaureate psychologists in their psychotherapy internship who practiced mindfulness meditation demonstrated a positive outcome in the treatment of their patients. Patients and psychotherapy trainees were randomly assigned to one of two groups: a group of patients treated by meditating trainees and a group of patients treated by trainees who did not meditate. Patient demographics and psychiatric disorders were similar for both arms of the study. Results of the study showed that patients treated by meditating therapists in training had significant improvements in the clarification and problem-solving effects of the therapy sessions compared with the control patients. In addition, symptom reduction on clinical scales for somatization, social insecurity, obsessiveness, anxiety, anger/hostility, and psychoticism was greater for the patients in the meditation group compared with that for the control patients. There was no difference in the positive relationship effects of therapy perceived by the patients in either arm of the study (41). These findings were gathered as part of the training of psychodynamic psychotherapists in Germany and warrant more study to generalize their findings to trainees in the United States.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Mindfulness meditation practices have a clear place in the treatment of psychiatric patients with regard to disorders of mood regulation, affect tolerance, and impulsivity. Because minimal side effects are associated with this mental training, its efficacy alone or associated with other modalities such as psychopharmacology, insight-oriented therapy, and CBT support its inclusion in the clinician's armamentarium. With the demonstrated positive effect of the clinician's practice of mindfulness meditation on treatment outcome for patients, ongoing studies of mindfulness-based therapies will have to take into account whether the therapist associated with control groups is engaged in mindfulness meditation. Training of medical professionals in mindfulness meditation should be further studied in this era of competency-based medical education, which emphasizes the maintenance of self-care and empathic communication as fundamental skills in professionalism and interpersonal communication. Mindfulness is a universal human mental capacity that enhances mental and emotional agility and interpersonal communication skills, which can be cultivated regardless of religious persuasion. The integration of mindfulness practices into psychodynamic and cognitive behavior psychotherapies is a growing area of clinical exploration. Early studies using mindfulness training in therapy show increased efficacy of the treatment for patients with numerous medical and psychiatric conditions as well as growing evidence of the enhanced efficacy for the patient when the clinician practices mindfulness. Future exploration will include

1) refinement in our definition of mindfulness, taking into account the various philosophical, spiritual, cultural, and intellectual traditions that practice mental training,

2) understanding the biological mechanisms of mindfulness in mental functioning,

3) understanding the essentials of mindfulness training and how best to teach mindfulness skills, and

4) further research to establish mechanisms of mindfulness and specific efficacy in the treatment of patients (42).

1 Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J: Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA 2008; 300:1350–1352 Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Epstein RM: Mindful practice. JAMA 1999; 282:833–839 Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Kabat-Zinn J: Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2003; 10:144–156 Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Germer CK: Mindfulness: What is it? What does it matter? in Mindfulness and Psychotherapy. Edited by Germer CK, Siegel RD, Fulton PR. New York, Guilford, 2005, pp 3–27 Google Scholar

5 Melbourne Academic Mindfulness Interest Group: Mindfulness-based psychotherapies: a review of conceptual foundations, empirical evidence and practical considerations. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2006; 40:285–294 Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, Peterson LG, Fletcher KE, Pbert L: Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:936–943 Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Linehan MM: Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 63–69 Google Scholar

8 Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 144–147 Google Scholar

9 Stepp SD, Epler AJ, Jahng S, Trull TJ: The effect of dialectical behavior therapy skills use on borderline personality disorder features. J Pers Disord 2008; 22:549–563 Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Weiss M, Nordlie JW, Siegel EP: Mindfulness-based stress reduction as an adjunct to outpatient psychotherapy. Psychother Psychosom 2005; 74:108–112 Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD: Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. New York, Guilford, 2002 Google Scholar

12 Ma SH, Teasdale JD: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72:31–40 Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Hayes SC: Get Out of Your Mind and into Your Life: The New Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oakland, CA, New Harbinger Publications, 2005 Google Scholar

14 Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA Freedman B: Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol 2006; 62:373–386 Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Childs D: Mindfulness and the psychology of presence. Psychol Psychother 2007; 80:367–376 Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Garland E, Gaylord S, Park J: The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore (NY) 2009; 5:37–44 Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Germer CK, Siegel RD, Fulton PR (eds): Mindfulness and Psychotherapy. New York, Guilford, 2005 Google Scholar

18 Shapiro SL, Carlson LE: The Art and Science of Mindfulness: Integrating Mindfulness into Psychology and the Helping Professions. Washington DC, American Psychological Association, 2009 Google Scholar

19 Kingston J, Chadwick P, Meron D, Skinner TC: A pilot randomized control trial investigating the effect of mindfulness practice on pain tolerance, psychological well-being, and physiological activity. J Psychosom Res 2007; 62:297–300 Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E: Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relations to quality of life, mood symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med 2003; 65:571–581 Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, Chroniak C, Durazo R, Mathews HL: Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun 2008; 22:969–981 Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Barrows K: The application of mindfulness to HIV. Focus: A Guide to AIDS Research and Counseling. UCSF. 2006 21: 1–4. www.ucsf-ahp.org Google Scholar

23 Sullivan MJ, Wood L, Terry J, Brantley J, Charles A, McGee V, Johnson D, Krucoff MW, Rosenberg B, Bosworth HB, Adams K, Cuffe MS: The support, education, and research in chronic heart failure study (SEARCH): a mindfulness-based psychoeducational intervention improves depression and clinical symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J 2009; 157:84–90 Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Nickels MW, Privitera MR, Coletta M, Sullivan P: Treating depression: psychiatric consultation in cardiology. Cardiol J 2009; 16:279–293 Google Scholar

25 Vieten C, Astin J: Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention during pregnancy on prenatal stress and mood: result of a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2008; 11:67–74 Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Lustyk MK, Gerrish WG, Shaver S, Keys SL: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health 2009; 12:85–96 Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Ong JC, Shapiro SL, Manber R: Combining mindfulness meditation with cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia: a treatment-development study. Behav Ther 2008; 39:171–182 Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Evans S, Ferrando S, Findler M, Stowell C, Smart C, Haglin D: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord 2008; 22:716–721 Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Kingston T, Dooley B, Bates A, Lawlor E, Malone K: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychol Psychother 2007; 80:193–203 Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Kenny MA, Williams JMG: Treatment-resistant depressed patients show a good response to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Behav Res Ther 2007; 45:617–625 Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Harley R, Sprich S, Safren S, Jacobo M, Fava M: Adaptation of dialectical behavior therapy skills training group for treatment-resistant depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 2008; 196:136–143 Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Birnbaum L, Birnbaum A: In search of inner wisdom: guided mindfulness meditation in the context of suicide. Sci World J 2004; 4:216–227 Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Hepburn SR, Crane C, Barnhofer T, Duggan DS, Fennell MJV, Williams JMG: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy may reduce thought suppression in previously suicidal participants: findings from a preliminary study. Br J Clin Psychol 2009; 48:209–215 Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Lazar SW. Mindfulness research, in Mindfulness and Psychotherapy. Edited by Germer CK, Siegel RD, Fulton PR. New York, Guilford, 2005, pp 220–240 Google Scholar

35 Lazar SW, Bush G, Gollub RL, Fricchione GL, Gurucharan K, Benson H: Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation. Neuroreport 2000; 11:1581–1585 Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, Urbanowski F, Harrington A, Bonus K, Sheridan JF: Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med 2003; 65:564–570 Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Stein DJ, Ives-Deliperi V, Thomas KGF: Psychobiology of mindfulness. CNS Spectr 2008; 13:752–756 Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Shapiro SL, Astin JA, Bishop SR, Cordova M: Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professional: result from a randomized trial. Int J Stress Manage 2005; 12:164–176 Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, Quill TE: Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA 2009; 302:1284–1293 Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Williams EN: A psychotherapy researcher's perspective on therapist self-awareness and self-focused attention after a decade of research. Psychother Res 2008; 18:139–146 Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Grepmair L, Mitterlehner F, Loew T, Bachler E, Rother W, Nickel M: Promoting mindfulness in psychotherapists in training influences the treatment results of their patients: a randomized double-blind, controlled study. Psychother Psychosom 2007; 76:332–338 Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Shapiro SL: The integration of mindfulness and psychology. J Clin Psychol 2009; 65:555–560 Crossref, Google Scholar