Depression and Access to Treatment Among U.S. Hispanics: Review of the Literature and Recommendations for Policy and Research

Abstract

Ethnic and racial diversity in the United States increases daily through immigration and population shifts, and multiculturalism in the mental health field has had a difficult time keeping pace. Delivery of adequate mental health care to Hispanics, now the largest and fastest-growing ethnic minority, has been plagued by low utilization rates and inadequate or delayed mental health services. Among the issues compounding the problem are the diversity that exists within the Hispanic population, the varied ways that symptoms are experienced and expressed, and the unique sets of risk factors and barriers facing U.S. Hispanic groups. This review provides an epidemiologic overview of the mental health status of the three largest U.S. Hispanic subgroups, with particular attention to diagnosis and treatment of major depressive disorder. Also discussed is the gap between the need for and the delivery of services, which is characterized in terms of problems with access to care, utilization of mental health services, and quality of care. Mental health research on Hispanic populations is relatively sparse. The data summarized here suggest that although response to antidepressant treatment is comparable between Hispanics and the general population, treatment compliance appears to be an area of concern. Research needs and other efforts to improve mental health care and treatment outcomes in Hispanics are addressed.

A growing appreciation of multiculturalism in the United States was apparent in the mental health field with the publication of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) in 1994. Because previous versions were seen as lacking in cultural sensitivity, DSM-IV introduced an Outline for Cultural Formulation to guide clinicians in factoring cultural context into their diagnoses, and a Glossary of Culture-Bound Syndromes to help illustrate the diversity of clinical presentations. Although it may be argued that placing the Outline and Glossary in an appendix rather than in the main text serves to marginalize consideration of culture in diagnosis (1), the inclusion of these two items nevertheless represented an acknowledgment that not all cultures experience mental disorders in ways that conform to DSM descriptions. In the decade that has passed since then, however, the distance between the acknowledgment of cultural diversity and the existence of a system in which all populations can and do receive adequate mental health care has become all the more apparent.

Population diversity has increased since 1970, with the proportion of the U.S. population that is foreign born growing from 5% to approximately 10% by 2000. This trend has been largely driven by Latin American immigrants, whose numbers rose from 19% of the foreign-born population to 51% over the same period (2). Consequently, the Hispanic population has emerged as the largest U.S. ethnic minority, with 37.4 million people constituting 13.3% of the U.S. population in 2002 (3). Furthermore, the growth of the Hispanic population is expected to remain strong, with Hispanics representing nearly one-quarter of U.S. citizens in 2050 (4).

Evolving less vigorously is the state of mental health care for U.S. Hispanic populations. Several studies suggest a significant gap between needs and care among Hispanics for illnesses such as major depressive disorder that is manifested by low rates of utilization (5, 6) and inadequate or delayed service (7, 8). This gap is the result of a complex mix of patient and system factors, many of them cultural, economic, and organizational in nature. Only a limited amount of research has been undertaken to explore these factors, and a great deal is yet to be learned about why so many Hispanics are not receiving adequate mental health care.

The Hispanic Psychiatry Education Initiative (HPEI) is one effort dedicated to reducing the gap between need and treatment. Among the activities of the HPEI are the development and maintenance of a knowledge base that characterizes the mental health climate for U.S. Hispanics; the information gleaned in that effort is summarized in this paper. Discussion about developing such a knowledge base began at a 2004 meeting of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry; subsequent meetings helped refine the information, and a corresponding electronic slide set was created and is available to organizations and individuals who share HPEI aims. The purpose of HPEI is to generate greater awareness of the cultural, economic, and organizational barriers to the delivery of psychiatric care to Hispanics as well as to focus attention on the need for more research to better understand and address these barriers.

Most of the material in this article focuses on major depressive disorder, which is among the most common, best studied, and most costly of mental disorders. Moreover, depression is projected to be the leading cause of disease burden by 2020 (9). HPEI’s scope is expected to broaden as the effort matures and more research involving Hispanic populations becomes available.

Epidemiology

Hispanics are linked primarily by a common language derived from Spain as well as by some aspects of ethnic heritage (10). The U.S. Census Bureau defines Hispanics as persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central and South American, or other Hispanic heritage, with the latter two options functioning as catchall categories for smaller subgroups. In 2002, 66.9% of U.S. Hispanics were Mexican, 8.6% were Puerto Rican, and 3.7% were Cuban (3). These are the three largest subgroups, and they are the most studied in mental health research (10).

Hispanics are more geographically concentrated than non-Hispanic whites, with nearly 8 out of 10 living in southern and western states. They also are more likely to live inside the central cities of metropolitan areas and less likely than non-Hispanic whites to live in nonmetropolitan areas (3). The largest Mexican populations live in California, Texas, Illinois, and Arizona; the largest Puerto Rican populations reside in New York, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania; and the majority of Cuban Americans call Florida home. Perhaps more indicative of future trends are clusters of Hispanics who live in states not historically associated with Hispanic settlement, such as North Carolina, Georgia, and Iowa, representing as much as a quarter of a given county’s population (11).

Evidence of disease burden

Research on the prevalence of depression among Hispanics provides some perspective on the heterogeneity of the three largest subgroups, and the representation of each group in the literature is roughly proportional to their relative sizes. The largest, most recent study (12), using data from the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), showed that Mexican Americans generally face a lower risk of depression than do non-Hispanic whites. This conclusion echoes analyses (13, 14) of data collected in the early 1980s for the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (15) and the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (H-HANES) (16). NESARC data also confirm that Mexican immigrants are approximately half as likely as their U.S.-born counterparts to experience mental disorders, as demonstrated earlier with ECA data (17) and the Mexican American Prevalence and Services Survey (MAPSS) (18). These earlier studies further concluded that acculturation appears to work against the immigrant advantage; MAPSS data showed that the estimated lifetime mental disorder rate for immigrants who had lived in the United States for more than 13 years was nearly double that for more recent immigrants.

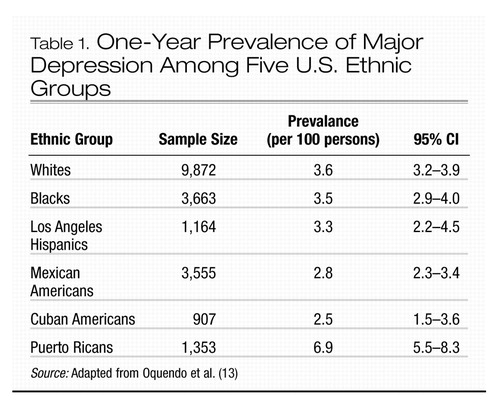

U.S. Puerto Ricans appear to face greater mental health risks, as suggested by data showing current, 6-month, 1-year, and lifetime depression rates more than double those for Mexican Americans and Cuban Americans (13, 16). Furthermore, Puerto Ricans are almost twice as likely as whites to have depression in a given year (Table 1). The situation is not much better in Puerto Rico, where the proportion of the population experiencing elevated symptoms of depression is similar to that for U.S. Puerto Ricans (19) and the overall prevalence of mental disorders is similar to that for the general U.S. population (20). This similarity between island Puerto Ricans and the U.S. population has been attributed to the industrial and economic development of the island and unrestricted circular migration between the mainland and Puerto Rico (20). Still, there is some evidence of a greater risk of depression in the U.S., such as data suggesting that the lifetime rate of depression for Puerto Ricans in New York City is nearly twice that for island Puerto Ricans (16, 20).

Mental health data on Cuban Americans are relatively sparse, in part because the ECA study did not include Cuban Americans. Furthermore, a lack of data on mental disorders within Cuba precludes assessment of any potential immigration correlation. The H-HANES reported lifetime, 6-month, and 1-month prevalence rates of major depressive disorder of 3.15%, 2.12%, and 1.5%, respectively, for Cuban Americans, which is comparable to rates for Mexican Americans and less than half the rates for Puerto Ricans (21).

An evaluation of the depression burden borne by Hispanics also requires consideration of the effects of culture on illness presentation. The acceptability of psychiatric care varies among cultures and depends in part on the ways in which mood disturbances are perceived (22). Cultures that are less accustomed, willing, or able to consider mood disturbances to be psychiatric disorders are more likely to express them as somatic complaints (23). Some data have indicated higher rates of somatization among Puerto Ricans (24) and Mexican American women over the age of 40 years (25), compared to non-Hispanic whites. Other research (26) has suggested that structured diagnostic interviews may yield artificially high rates of somatization because of cultural differences in language usage and utilization of care.

Similarly, clinicians need to be cognizant of the disparate folk constructs various ethnic groups hold regarding mental health problems. Many of these, including susto (fright), nervios (nerves), and mal de ojo (evil eye), are listed in the DSM-IV Glossary of Culture-Bound Syndromes, and a number of articles (27–31) have characterized these folk syndrome patterns and their overlap with DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic entities. Engaging patients in ways that honor their conceptions of illness is essential to formulating accurate diagnoses and establishing therapeutic alliances.

Research on substance use and suicide prevalence provides additional perspective on the heterogeneity of mental health burden and subpopulations, although coverage of the literature is beyond the scope of this review. Data on these topics were collected in conjunction with NESARC, H-HANES, the ECA study, and the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (32), and a number of reviews are available. Similarly, literature reviews dedicated to the challenges facing younger and older Hispanics contribute to our understanding of Hispanic mental health across the life cycle.

Potential influences on disease burden

A number of causes and contributing factors have been proposed for the mental health burdens borne by U.S. Hispanics, most of which similarly influence the risks other cultures face. Examples of shared risk factors for depressive symptoms include female gender (18, 33, 34), low educational achievement (19, 34–36), low income (19, 33–35), unemployment (19, 21, 36), and medical comorbidity (37). In the Hispanic population, the prevalence of some factors is greater. Only 57% of Hispanics age 25 years and older have completed high school, compared with nearly 89% of non-Hispanic whites, and more than one-quarter have less than a ninth-grade education, compared with 4% of non-Hispanic whites. Furthermore, Hispanics are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to live in poverty (21.4% vs. 7.8%) and to be unemployed (8.1% vs. 5.1%) (3).

Risk factor logic hits a snag, however, in consideration of Mexican American immigrants, who have lower levels of income and education as well as lower rates of depression (12, 17, 18). This finding is consistent with the “Hispanic paradox” concept that emerged as public health researchers began noting better findings on a number of health measures (e.g., birth weight and mortality from cardiovascular causes) than typically is associated with lower socioeconomic status (38). The concept has been refined through subsequent research, such as in an analysis of adult mortality data (39) suggesting that the benefit is limited to immigrant Mexican Americans and other Hispanic immigrants who are not Puerto Rican or Cuban. Additional perspective on demographic risk factors is provided in a study (33) that found few statistically significant differences in prevalence or severity of depression among whites and ethnic subgroups once results were adjusted for demographic differences such as gender and income.

The act of making a life within a new culture appears to carry its own risks. Marital dysfunction (e.g., divorce and separation) increases in the second and third postimmigration generations (40, 41) and is associated with a greater risk of depression (16, 42). Burnam et al. (17) reviewed ECA data using a multidimensional scale of acculturation and found that U.S.-born Mexican Americans were more acculturated than those born in Mexico. They also suffered from the highest rates of mental disorders of any ECA subgroup, even after age, sex, and marital status were controlled for. Ortega et al. (43) reached a similar conclusion in an analysis of NCS data. A third study (44) found a positive correlation between acculturation and risk of depression among younger Mexican Americans (20–30 years of age) but not their older counterparts.

Consideration of the social, economic, and political factors leading to emigration may also help explain variations in mental health burden. Mexican and Puerto Rican emigration has been driven generally by economic need, whereas for Cubans and South and Central Americans, it is more likely related to political dissent and seeking asylum as refugees (45). Central and South American immigrants in particular may have fled political or war-related trauma that would place them at higher risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (46). Political refugees also may be more likely to experience a reduction in socioeconomic status and associated distress.

Health services

The inadequacy of mental health care for U.S. Hispanics may be attributed to both patient and system factors. Examples of patient factors undermining access to care include socioeconomic position, language proficiency, and citizenship status. System factors encompass issues related to the delivery and reimbursement of care. Access to care, utilization of care, and quality of care all are in need of improvement for Hispanic populations.

Access to care

Effective care is central to improvement of mental health services, if only because concepts such as utilization and quality of care mean little without it. Moreover, effective access requires that patients be able to navigate the health care system beyond an initial visit or two. This is true particularly for mental health care, for which ongoing treatment is the norm. Thus, access to care should be regarded as the ability to enter the care system plus the ability to receive care on an ongoing basis.

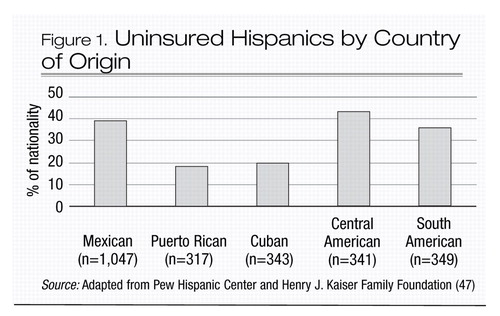

With one in five living in poverty (3), Hispanics are more likely to live in resource-poor neighborhoods and to have no income available for mental health care. More than one-third lack health insurance, despite the fact that almost two-thirds of the uninsured are employed (47), which suggests disproportionate employment in occupations that do not offer health care benefits. Moreover, the proportion of Hispanics lacking health insurance has been on the rise (48, 49), and lack of coverage is the primary reason Hispanics are more likely than whites to report unmet medical needs, not to have a regular health care provider, and not to have seen a physician within the past year (50). As with other variables discussed here, the likelihood of having insurance coverage varies by national origin (Figure 1) (47). Puerto Ricans are more likely than Mexican Americans to be insured because their status as U.S. citizens makes them eligible for publicly funded health benefits. Cuban Americans benefit both from refugee status and elevated socioeconomic standing and are more likely to have private insurance (51, 52).

Although broadly predictive of access to care, disparities in income and health insurance coverage do not account fully for access disparities (53, 54). A study (55) of immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican Americans showed that knowing where to find a provider increased the likelihood that a person would seek and use specialty mental health care. Indeed, the U.S. health care system is among the most complex in the world and presents barriers to natives as well. Language is a significant issue (56), with nearly three of every 10 Hispanics reporting problems communicating with providers (47). Related to the language barrier is the relative scarcity of U.S. mental health professionals of Hispanic origin. There are approximately 29 Hispanic providers per 100,000 Hispanics, compared with 173 white providers per 100,000 non-Hispanic whites (57). With fewer culturally proficient professionals, geographic distribution of providers is very likely another issue, particularly for rural Hispanics and the more recently formed Hispanic population clusters. Employment circumstances also may represent a barrier if provider availability during non-work hours is limited. Moreover, even finding non-work hours may be a challenge, as it is not uncommon for Hispanic heads of household to work two or three jobs to provide for their families.

Utilization of care

Additional factors contributing to inadequate mental health care for U.S. Hispanics are evident in utilization patterns. Mexican Americans in the ECA study who had experienced mental disorders within the previous 6 months were only half as likely as whites (11% vs. 22%) to use health or mental health services (5). Mexican Americans with psychiatric disorders also are more likely to receive care from general medical care providers than mental health specialists, particularly in rural areas (6). Among Mexican Americans who had a psychiatric disorder in the previous year, the U.S. born are seven times more likely than the foreign born to have seen a psychiatrist (8.8% vs. 1.2%) and three times more likely to have visited any mental health specialist (13.4% vs. 4.0%) (55).

Fewer data are available to characterize Puerto Ricans and Cuban Americans, among whom utilization of care generally is thought to be higher. Obtaining care may be more ingrained in Puerto Rican culture. In a study of poor island dwellers (58), 32% of those who met criteria for mental health care need received at least some care within the previous year. Like Mexican Americans, patients in this study were more likely to seek care for mental health in the medical care sector. An expenditures study (52) demonstrated that Puerto Ricans had the highest annual medical expenses and were more likely to have had at least one physician visit in the previous year, compared with Mexican and Cuban Americans. Greater utilization among Cuban Americans has been attributed to greater access to public care because of refugee status (51), higher rates of private insurance (52), and greater familiarity with American-style care delivery (52, 59).

Lower socioeconomic status has been linked to lower utilization regardless of insurance status (60, 61). Language barriers probably influence utilization, as evidenced by a study (62) that found that Hispanics with fair or poor English proficiency had 22% fewer physician visits than non-Hispanics. Similarly, the relative lack of Hispanic providers appears to be a factor. Mexican Americans with ethnically matched therapists have been found to remain in treatment longer and to have better outcomes (63). Moreover, minority patients characterize their physicians’ decision making as less participatory than do nonminorities (64), and patients in race-concordant therapeutic relationships rate their visits as significantly more participatory than do those in race-discordant dyads (65).

Utilization also may be affected by help seeking directed toward other sources. Not only were Mexican Americans who had a psychiatric disorder within the previous year more likely to see a general medical professional (19.9%) than a mental health specialist (9.3%), they also were more likely to see other professionals, including priests, chiropractors, and counselors (11.2%). Patients saw informal sources such as folk healers, spiritualists, and psychics less frequently (4.5%) (55).

Finally, bias and prejudice probably exert some influence on utilization. After Proposition 187 was passed by California voters, making illegal immigrants ineligible for public health services, use of outpatient mental health services by younger Hispanics dropped by 26% and use of crisis services increased (66). Health care professionals may unintentionally incorporate bias or stereotypes in the course of assessment or treatment (67, 68), leading patients to reject treatment recommendations. Patients, too, may have negative attitudes toward mental health care that are based on the experiences of others (55, 69), resulting in avoidance.

Quality of care

Mental health care for U.S. Hispanics is compromised by lower quality of care. Here again, language represents a significant obstacle, as quality of care depends on the quality of the communication between provider and patient. In medical care settings, language barriers have been associated with less discussion of medication side effects and potentially poorer compliance (70), reduced question asking and patient recall of clinician encounters (71), and lower utilization of preventive health screening (72, 73). Clear communication becomes all the more crucial in mental health care, which requires a shared understanding of subjectively experienced symptoms.

Uncertainty in interpreting disease symptoms in minorities leads to differences in care, a dynamic known as statistical discrimination (74), which has been shown to affect the diagnosis of depression, hypertension, and diabetes (75). In a study of pediatric emergency department data (76), the presence of a language barrier was associated with significantly higher charges related to diagnostic tests. Although expensive diagnostic tests are less likely to be an issue in mental health settings, this finding nevertheless suggests that communication difficulties often leave providers without the information needed for accurate diagnosis.

High utilization of general or family practitioners to address depression-based symptoms is another potential influence on overall quality of care, with some data (77) suggesting that Hispanics are less likely than whites to obtain mental health diagnoses in the primary care setting. Furthermore, among patients with self-perceived need for treatment for substance use or other mental disorders, most of whom utilized primary care providers, Hispanics were significantly more likely than whites to report less care than needed or delayed care (22.7% vs. 10.7%) (7). An alternative perspective, however, is provided in a study (78) suggesting that primary care providers recommend depression treatments equally to Hispanic and white patients but that Hispanics are less likely to take antidepressants and to obtain specialty mental health care.

Still, use of mental health providers does not guarantee higher quality of care, as suggested by data from community health clinics showing that minorities are significantly less likely than nonminorities to receive a treatment recommendation to take an antidepressant (79). Similarly, a review of National Ambulatory Medical Care data found that minorities were approximately half as likely to have office visits documenting antidepressant therapy, a diagnosis of depressive disorder, or both (8). In a study comparing psychiatric emergency service diagnoses with those obtained subsequently via structured interview (80), diagnostic agreement was significantly more likely for white than for nonwhite patients. The diagnostic disagreement was attributable to information variance associated with the patient’s race in nearly 60% of cases. Finally, a large study of psychiatric outpatients (81) found that Hispanics were approximately 74% more likely than European and African Americans to receive a diagnosis of major depressive disorder and that although Hispanics had the highest level of self-reported psychotic symptoms, African Americans were almost twice as likely to receive a diagnosis from the schizophrenia spectrum of disorders. Among the potential causes of misdiagnosis cited by the authors are cultural variance in the behavioral repertoire (e.g., symptoms that are indicative of psychosis in one culture but more normative in another) and diagnostic bias.

Treatment

The paucity of data on treatment of depression for Hispanic populations is startling. This state of affairs is due in part to a lack of Hispanic participation in clinical research (82). Although National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding generally requires minority representation in trials, the lack of marked differences in depression treatment outcomes in cross-national studies (83–87) may have encouraged modest interest in ethnicity-specific research from investigators and the pharmaceutical industry. The results of studies conducted with largely or entirely Caucasian populations have been regarded as applicable to Hispanics. Although generally not harmful, such assumptions necessarily gloss over distinct characteristics that may moderate the computed risk of illness for distinct ethnic populations. In planning culturally competent mental health care, leveraging protective elements while minimizing risk factors is an essential goal.

Few trials have assessed the efficacy of antidepressants in Hispanics. Although early studies involved small samples and other factors limiting generalization of results, some conclusions are confirmed by more recent findings. Hispanics in these initial trials responded at least as well to antidepressants as non-Hispanics did (85, 86) or as compared with standard U.S. response rates (84). An early comparative trial that reported discontinuation rates (86), the only one to do so, found that Hispanics were more likely than non-Hispanics to complain about side effects and to discontinue the antidepressant despite receiving roughly half the dosage. Finally, the core symptoms of depression generally were consistent across cultures, with variation seen in somatization indexes, psychomotor components of depression, and levels of psychopathology (85, 86, 88).

A more recent study (87) concluded that optimal dosage levels, response, and tolerability are comparable for Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. This open-label trial of nefazodone with 50 Spanish-monolingual Hispanics with major depressive disorder was conducted in an outpatient clinic specializing in the treatment of depressive disorders in Hispanics, and results were compared with historical controls among English-speaking, predominantly non-Hispanic patients. Discontinuations, however, fell beyond the typical range for nefazodone (42% vs. 21%–33%); side effects and family and work demands were cited as the cause for the majority of discontinuations. The authors noted that the study patients either responded, as reflected in the 90% completer response rate, or discontinued, and no significant associations could be detected between discontinuation and demographic or clinical variables.

A smaller pilot study (83) compared fluoxetine treatment and interpersonal psychotherapy for 12 weeks in Spanish-monolingual patients with major depressive disorder. Twenty subjects received either one 45-minute interpersonal psychotherapy session weekly or fluoxetine. The majority of completers in both groups (67%) responded, but only 40% of interpersonal psychotherapy subjects and 50% of fluoxetine subjects completed the trial, with just one discontinuation due to adverse events. The results of these trials suggest that treatment is likely to be effective for Hispanics who adhere to the treatment.

Additional information comes from an open-label, naturalistic trial of escitalopram (89) with 5,453 patients with major depressive disorder, including 143 Hispanics. When the Hispanic subpopulation was compared with the whole (data on file, Forest Laboratories), the overall mean dose at the endpoint was found to be similar. Hispanics who finished the 8-week study were as likely as the general population to respond (73.3% vs. 73.1%), although the dropout rate was higher among Hispanics (38.5% vs. 23.9%). Discontinuation was due primarily to higher rates of adverse events (11.9% vs. 8.7%) and loss to follow-up (11.9% vs. 8.3%).

Together these studies suggest that Hispanics who undergo an adequate antidepressant trial (i.e., 6–8 weeks) are as likely as non-Hispanics to respond but that Hispanics may be more likely to discontinue treatment. In addition to variations in risk of illness, it may be that Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites face differential risks regarding the tolerability and efficacy of medications. Questions of whether study samples have been representative of the general Hispanic population limit the predictive power of these studies. Sample sizes have been prohibitively small, and it may be argued that Hispanics who are obtaining mental health care are more acculturated than others, in which case dropout rates may be underestimated and response rates overestimated.

Although an exploration of the psychology literature involving Hispanics is beyond the scope of this review, some studies involving cognitive behavior therapy have demonstrated the value of care that reflects the realities of the patient population. Over a 5-year span in 46 primary care clinics (90), quality improvement initiatives, such as training in cultural sensitivity, collaborative care, and bilingual cognitive behavior therapy, minimized the disparity in risk of depression between minorities and Caucasians. In another study of impoverished primary care patients (91), the addition of clinical case management (including telephone outreach and home visits) to cognitive behavior therapy reduced treatment discontinuations for all patients and improved symptoms and functioning in those whose first language was Spanish.

Conclusions and recommendations

The reasons that U.S. Hispanics as a group receive substandard mental health care are, like the cultures that qualify as Hispanic, numerous and diverse. Although this complexity frustrates the desire for uncomplicated solutions (e.g., allocating more money to developing care for Hispanics), it also means that the opportunities for improvement also are many and varied, which suggests a campaign that can be conducted on a number of smaller and potentially more manageable fronts. Given the rapid growth of the Hispanic population and the rising proportion that is uninsured, perhaps the primary targets for reducing mental health care disparities should be those related to access to care. It is incumbent upon the mental health field to advocate for greater access, with solutions likely to be rooted in public policy, creative approaches, or both.

Research and action also are required to help improve interaction between U.S. Hispanics and the mental health care system. NIH requirements for minority inclusion probably have boosted Hispanic representation in trials, although the need for a deeper understanding of ethnicity’s effects remains. Of the many areas that deserve attention, the following have emerged as priorities in the course of HPEI work.

Updating DSM.

DSM-IV acknowledged that culture can influence disease presentation. The next version must reflect the fact that cultural diversity becomes more the mainstream in the United States with every passing day. Cultural considerations cannot be relegated to an appendix but instead must be addressed in descriptions of diagnostic categories.

Deconstructing “Hispanic.”

Although much research necessarily has grouped all Spanish-speaking persons together as Hispanics, our growing understanding of cultural diversity increasingly renders the practice inadequate in mental health care. Central and South American cultures are particularly underrepresented in the literature, and studies are needed to help characterize mental health in these populations.

Understanding immigration.

The factors protecting the mental health of some immigrants and the apparent deleterious effects of U.S. acculturation on others are poorly understood. Further research may help answer questions surrounding these issues and lead to better therapeutic strategies.

Performing triage.

Puerto Ricans appear to bear the most significant mental health burden of the groups discussed, so it may be argued that their need is the most acute. Greater understanding of the causes would aid efforts to reduce this disparity.

Boosting recruitment.

Reduction of cultural barriers to effective mental health care depends on increasing the ranks of Hispanic mental health care professionals. Furthermore, geographic areas experiencing Hispanic population growth must take steps to attract and develop ethnically appropriate providers.

Improving adherence.

Although the literature suggests some reasons why Hispanics appear to discontinue treatment more frequently than non-Hispanics, studies are needed to develop practical methods for keeping patients engaged.

Digging deeper.

Pharmacogenetic research seeks to identify hereditary correlates for human interaction with medications, and further efforts in Hispanic populations may yield information about such issues as tolerability.

Mobilizing support.

Extending care among disadvantaged populations requires resources as well as individuals to champion the cause. Securing these in the absence of current data that quantify disparities in care would be a daunting challenge under the best of circumstances, which underscores the need for continued research in addition to the commitment and ability to act when data become available.

Mental health care has never been a field in which one-size-fits-all solutions have proven particularly fruitful, and this fact becomes increasingly relevant in the context of the growing cultural diversity in the United States. The more the care delivered reflects the realities of the people for whom it is intended, the less energy will be required to analyze and eliminate disparities.

|

Table 1. One-Year Prevalence of Major Depression Among Five U.S. Ethnic Groups

Figure 1. Uninsured Hispanics by Country of Origin

1 Lewis-Fernandez R: Cultural formulation of psychiatric diagnosis. Cult Med Psychiatry 1996; 20:133–144Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Adding diversity from abroad: The foreign-born population, 2000, in Population Profile of the United States: 2000 (Internet release). Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2000, chapter 17Google Scholar

3 Ramirez RR, de la Cruz GP: The Hispanic population in the United States: March 2002. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2003Google Scholar

4 US interim projections by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2004Google Scholar

5 Hough RL, Landsverk JA, Karno M, Burnam MA, Timbers DM, Escobar JI, Regier DA: Utilization of health and mental health services by Los Angeles Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:702–709Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Catalano R: Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:928–934Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:2027–2032Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL, Galin RS: Ethnicity and the prescribing of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: 1992–1995. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1999; 7:29–36Google Scholar

9 Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds): Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment or Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

10 Garza-Trevino ES, Ruiz P, Venegas-Samuels K: A psychiatric curriculum directed to the care of the Hispanic patient. Acad Psychiatry 1997; 21:1–10Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Guzman B: Census 2000 brief: the Hispanic population. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2001Google Scholar

12 Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Anderson K: Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:1226–1233Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Oquendo MA, Ellis SP, Greenwald S, Malone KM, Weissman MM, Mann JJ: Ethnic and sex differences in suicide rates relative to major depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1652–1658Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Oquendo MA, Lizardi D, Greenwald S, Weissman MM, Mann JJ: Rates of lifetime suicide attempt and rates of lifetime major depression in different ethnic groups in the United States. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 110:446–451Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Robins LN, Reiger DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

16 Moscicki EK, Rae DS, Regier DA, Locke BZ: The Hispanic health and nutrition survey: depression among Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans, in Research Agenda for Hispanics. Edited by Garcia M, Arana J. Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1987, pp 145–159Google Scholar

17 Burnam MA, Hough RL, Karno M, Escobar JI, Telles CA: Acculturation and lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. J Health Soc Behav 1987; 28:89–102Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J: Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:771–778Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Vera M, Alegria M, Freeman D, Robles RR, Rios R, Rios CF: Depressive symptoms among Puerto Ricans: island poor compared with residents of the New York City area. Am J Epidemiol 1991; 134:502–510Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Canino GJ, Bird HR, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bravo M, Martinez R, Sesman M, Guevara LM: The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rico. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:727–735Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Narrow WE, Rae DS, Moscicki EK, Locke BZ, Regier DA: Depression among Cuban Americans: the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990; 25:260–268Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Kirmayer LJ: Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: implications for diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 13):22–28; discussion 29–30Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Escobar JI: Transcultural aspects of dissociative and somatoform disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1995; 18:555–569Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Escobar JI, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Karno M: Somatic symptom index (SSI): a new and abridged somatization construct: prevalence and epidemiological correlates in two large community samples. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:140–146Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Escobar JI, Golding JM, Hough RL, Karno M, Burnam MA, Wells KB: Somatization in the community: relationship to disability and use of services. Am J Public Health 1987; 77:837–840Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Villasenor Y, Waitzkin H: Limitations of a structured psychiatric diagnostic instrument in assessing somatization among Latino patients in primary care. Med Care 1999; 37:637–646Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Liebowitz MR, Salman E, Jusino CM, Garfinkel R, Street L, Cardenas DL, Silvestre J, Fyer AJ, Carrasco JL, Davies S: Ataque de nervios and panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:871–875Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Salgado de Snyder VN, Diaz-Perez MJ, Ojeda VD: The prevalence of nervios and associated symptomatology among inhabitants of Mexican rural communities. Cult Med Psychiatry 2000; 24:453–470Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Koss-Chioino JD, Canive JM: The interaction of popular and clinical diagnostic labeling: the case of embrujado. Med Anthropol 1993; 15:171–188Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Guarnaccia PJ, Rivera M, Franco F, Neighbors C: The experiences of ataques de nervios: towards an anthropology of emotions in Puerto Rico. Cult Med Psychiatry 1996; 20:343–367Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Jenkins JH: Conceptions of schizophrenia as a problem of nerves: a cross-cultural comparison of Mexican-Americans and Anglo-Americans. Soc Sci Med 1988; 26:1233–1243Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Jackson-Triche ME, Greer Sullivan J, Wells KB, Rogers W, Camp P, Mazel R: Depression and health-related quality of life in ethnic minorities seeking care in general medical settings. J Affect Disord 2000; 58:89–97Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Moscicki EK, Locke BZ, Rae DS, Boyd JH: Depressive symptoms among Mexican Americans: the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 130:348–360Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Golding JM, Lipton RI: Depressed mood and major depressive disorder in two ethnic groups. J Psychiatr Res 1990; 24:65–82Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Munet-Vilaro F, Folkman S, Gregorich S: Depressive symptomatology in three Latino groups. West J Nurs Res 1999; 21:209–224Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Kemp BJ, Staples F, Lopez-Aqueres W: Epidemiology of depression and dysphoria in an elderly Hispanic population: prevalence and correlates. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987; 35:920–926Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Markides KS, Coreil J: The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public Health Rep 1986; 101:253–265Google Scholar

39 Palloni A, Arias E: Paradox lost: explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography 2004; 41:385–415Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Rumbaut RG: Assimilation and its discontents: between rhetoric and reality. Int Migr Rev 1997; 31:923–960Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Rumbaut RG: Ties that bind: immigration and immigrant families in the United States, in Immigration and the Family: Research and Policy on US Immigrants. Edited by Booth A, Crouter AC, Landale NS. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997, pp 3–46Google Scholar

42 Hovey JD, Magana CG: Exploring the mental health of Mexican migrant farm workers in the Midwest: psychosocial predictors of psychological distress and suggestions for prevention and treatment. J Psychol 2002; 136:493–513Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Ortega AN, Rosenheck R, Alegria M, Desai RA: Acculturation and the lifetime risk of psychiatric and substance use disorders among Hispanics. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:728–735Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Kaplan MS, Marks G: Adverse effects of acculturation: psychological distress among Mexican American young adults. Soc Sci Med 1990; 31:1313–1319Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Saez-Santiago E, Bernal G: Depression in ethnic minorities: Latinos and Latinas, African Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans, in Handbook of Racial and Ethnic Minority Psychology, vol 4. Edited by Bernal G, Trimble JE, Burlew AK, Leong FTL. London, Sage, 2003, pp 1–28Google Scholar

46 Farias P: Central and South American refugees: some mental health challenges, in Amidst Peril and Pain: The Mental Health and Well Being of the World’s Refugees. Edited by Marsella AJ, Bornemann S, Ekblad S, Orley J. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994, pp 101–113Google Scholar

47 Pew Hispanic Center and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: Health care experiences, 2002 National Survey of Latinos: survey brief. Pew Hispanic Center and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2004, pp 1–5Google Scholar

48 Doty MM, Holmgren AL: Unequal access: insurance instability among low-income workers and minorities. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2004; 729:1–6Google Scholar

49 Hargraves JL: The insurance gap and minority health care, 1997–2001. Track Rep 2002; 2:1–4Google Scholar

50 Hargraves JL, Hadley J: The contribution of insurance coverage and community resources to reducing racial/ethnic disparities in access to care. Health Serv Res 2003; 38:809–829Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Vega WA, Lopez SR: Priority issues in Latino mental health services research. Ment Health Serv Res 2001; 3:189–200Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Schur CL, Bernstein AB, Berk ML: The importance of distinguishing Hispanic subpopulations in the use of medical care. Med Care 1987; 25:627–641Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW: Racial and ethnic differences in access to and use of health care services, 1977 to 1996. Med Care Res Rev 2000; 57(Suppl 1):36–54Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM: Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA 2000; 283:2579–2584Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S: Help seeking for mental health problems among Mexican Americans. J Immigr Health 2001; 3:133–140Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Timmins CL: The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Womens Health 2002; 47:80–96Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar

58 Alegria M, Robles R, Freeman DH, Vera M, Jimenez AL, Rios C, Rios R: Patterns of mental health utilization among island Puerto Rican poor. Am J Public Health 1991; 81:875–879Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Portes A, Kyle D, Eaton WW: Mental illness and help-seeking behavior among Mariel Cuban and Haitian refugees in south Florida. J Health Soc Behav 1992; 33:283–298Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Escarce JJ, Puffer FW: Black-white differences in the use of medical care by the elderly, in Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Health of Older Americans. Edited by Martin LG, Soldo BJ. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1997, pp 183–209Google Scholar

61 Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Stoddard JJ: Children’s access to primary care: differences by race, income, and insurance status. Pediatrics 1996; 97:26–32Google Scholar

62 Derose KP, Baker DW: Limited English proficiency and Latinos’ use of physician services. Med Care Res Rev 2000; 57:76–91Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu LT, Takeuchi DT, Zane NW: Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: a test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:533–540Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield S, Rogers W, Ware JE: Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision-making style: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care 1995; 33:1176–1187Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, Ford DE: Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA 1999; 282:583–589Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Fenton JJ, Catalano R, Hargreaves WA: Effect of Proposition 187 on mental health service use in California: a case study. Health Aff (Millwood) 1996; 15:182–190Crossref, Google Scholar

67 van Ryn M, Burke J: The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med 2000; 50:813–828Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, Dube R, Taleghani CK, Burke JE, Williams S, Eisenberg JM, Escarce JJ: The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:618–626Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995; 36:1–10Crossref, Google Scholar

70 David RA, Rhee M: The impact of language as a barrier to effective health care in an underserved urban Hispanic community. Mt Sinai J Med 1998; 65:393–397Google Scholar

71 Seijo R, Gomez H, Friedenberg J: Language as a communication barrier in medical care for Hispanic patients, in Hispanic Psychology: Critical Issues in Theory and Research. Edited by Padilla AM. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1995Google Scholar

72 Solis JM, Marks G, Garcia M, Shelton D: Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HHANES 1982–84. Am J Public Health 1990; 80(suppl):11–19Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Stein JA, Fox SA: Language preference as an indicator of mammography use among Hispanic women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990; 82:1715–1716Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Balsa AI, McGuire TG: Statistical discrimination in health care. J Health Econ 2001; 20:881–907Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Balsa AI, McGuire TG, Meredith LS: Testing for statistical discrimination in health care. Health Serv Res 2005; 40:227–252Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Hampers LC, Cha S, Gutglass DJ, Binns HJ, Krug SE: Language barriers and resource utilization in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 1999; 103:1253–1256Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB: Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? J Gen Intern Med 2000; 15:381–388Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Miranda J, Cooper LA: Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19:120–126Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Raue P: Predictors of antidepressant prescription and early use among depressed outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:690–696Google Scholar

80 Strakowski SM, Hawkins JM, Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, West SA, Bourne ML, Sax KW, Tugrul KC: The effects of race and information variance on disagreement between psychiatric emergency service and research diagnoses in first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:457–463Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Minsky S, Vega W, Miskimen T, Gara M, Escobar J: Diagnostic patterns in Latino, African American, and European American psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:637–644Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Evelyn B, Toigo T, Banks D, Pohl D, Gray K, Robins B, Ernat J: Participation of racial/ethnic groups in clinical trials and race-related labeling: a review of new molecular entities approved 1995–1999. J Natl Med Assoc 2001; 93(12 suppl):18S–24SGoogle Scholar

83 Blanco C: A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy versus fluoxetine in the treatment of depressed Hispanics, in Advancing the Next Generation of Latino Mental Health Research. San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2001Google Scholar

84 Escobar JI, Gomez J, Constain C, Rey J, Santacruz H: Controlled clinical trial with trazodone, a novel antidepressant: a South American experience. J Clin Pharmacol 1980; 20:124–130Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Escobar JI, Tuason VB: Antidepressant agents: a cross-cultural study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1980; 16(3):49–52Google Scholar

86 Marcos LR, Cancro R: Pharmacotherapy of Hispanic depressed patients: clinical observations. Am J Psychother 1982; 36:505–512Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Sanchez-Lacay JA, Lewis-Fernandez R, Goetz D, Blanco C, Salman E, Davies S, Liebowitz M: Open trial of nefazodone among Hispanics with major depression: efficacy, tolerability, and adherence issues. Depress Anxiety 2001; 13:118–124Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Escobar JI, Gomez J, Tuason VB: Depressive phenomenology in North and South American patients. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:47–51Crossref, Google Scholar

89 Rush AJ, Bose A: Escitalopram in clinical practice: results of an open-label trial in a naturalistic setting. Depress Anxiety 2005; 21:26–32Crossref, Google Scholar

90 Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Ettner S, Duan N, Miranda J, Unutzer J, Rubenstein L: Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:378–386Crossref, Google Scholar

91 Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, Dwyer E, Areane P: Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:219–225Crossref, Google Scholar