Surgical Nonpsychiatric Medical Treatment of Patients With Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Abstract

It appears that many individuals with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) receive nonpsychiatric medical treatment and surgery; however, this topic has had little systematic investigation. This study assessed the nonpsychiatric treatment sought and received by 289 individuals (250 adults and 39 children/adolescents) with DSM-IV BDD. Such treatment was sought by 76.4% and received by 66.0% of adults. Dermatologic treatment was most often received (by 45.2% of adults), followed by surgery (by 23.2%). These treatments rarely improved BDD symptoms. Results were similar in children/adolescents. These findings indicate that a majority of patients with BDD receive nonpsychiatric treatment but tend to respond poorly.

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), also known as dysmorphophobia, is a relatively common disorder (1, 2) that consists of a distressing and impairing preoccupation with a nonexistent or slight defect in appearance. It appears that these patients often seek surgical, dermatologic, and other nonpsychiatric medical treatment for their perceived appearance flaws and that the outcome is often poor (3–6). Studies have reported rates of BDD of 7% (7) and 15% (8) in patients seeking cosmetic surgery and a rate of 12% in patients seeking dermatologic treatment (9). However, the types of treatment sought by patients with BDD and the outcome of such treatment has received very little systematic investigation.

The surgery literature discusses patients with characteristics that have some overlap with BDD, such as “insatiable” surgery patients (10), patients with “minimal deformity” (11), “psychologically disturbed” patients (12), and “polysurgical addicts” (13). It is unclear, however, which and how many of these patients have DSM-IV-defined BDD. There are some suggestions that certain patients with minimal deformity or psychological disturbance are good surgical candidates (11, 12, 14). However, many authors caution against performing surgery on these patients, especially those identified as having BDD, because of poor outcomes that include dissatisfaction with the procedure (10, 15) or violence toward the surgeon (16–18). In particular, cosmetic surgery in men has been cited as sometimes generating aggression toward the surgeon, even triggering murder (16, 18).

The dermatology literature notes that individuals with “dermatological hypochondriasis” (19) or “dermatological non-disease” (20) who resemble patients with BDD, often seek dermatologic treatment, including laser therapy or dermabrasion (20). A number of authors state that these patients are often difficult to treat and frequently have a poor treatment outcome (20, 21–23). Case reports of patients with BDD seeking dental treatment or orthognathic surgery have been published, with mixed treatment outcomes reported (24, 25).

In reports from psychiatric settings, a relatively high percentage of BDD patients have sought and received nonpsychiatric treatment for their perceived appearance flaws (4–6, 26), which appears to rarely improve BDD symptoms (6, 26). However, the literature has been limited by small numbers of subjects, a lack of detailed description of treatment outcome and types of treatment sought and received, and a lack of data on why requested treatment is not received.

In this study, we assessed the frequency, types, and outcomes of nonpsychiatric medical, surgical, and dental treatment sought and received by 289 patients with BDD seen in a psychiatric setting. This is, to our knowledge, the largest series of patients with DSM-IV BDD. Because much of the surgical and dermatologic literature warns against treating patients with minimal or nonexistent defects, we determined how often, and why, BDD patients did not receive such treatment. And because some authors warn in particular against performing cosmetic surgery in men (16, 18), we determined whether men were more often refused surgery than women and whether surgical outcome was worse for men. In addition, we hypothesized that patients with more severe BDD symptoms and those with poorer insight would be more likely to seek and receive nonpsychiatric treatment.

Method

Subjects

Study subjects were 289 consecutive individuals with DSM-IV BDD (250 adults and 39 children/adolescents) who were evaluated and/or treated in a BDD research program. Patients with a delusional belief about their appearance flaws (delusional disorder, somatic type) were included because available data suggest that the delusional and nondelusional forms of BDD are variants of the same disorder (27), and they may be double-coded in DSM-IV. Informed consent/assent was obtained after the study was fully explained; for children, consent was also obtained from the child’s legal guardian.

A majority of the adults (62.0%; n=155) participated in a BDD phenomenology study, which has been described elsewhere (5), and 38.0% (n=95) participated in BDD pharmacotherapy studies (28). The adults had a mean age of 33.0±10.3 years (range=18–80); 52.4% (n=131) were female. Regarding marital status 66.4% (n=166) had never been married, 20.8% (n=52) were married, and 12.8% (n=32) were divorced. The mean age at BDD onset was 16.9±7.4 (range=4–43) years, with a mean duration of illness of 15.5±11.6 (range=<1–69) years. The 39 children and adolescents participated in a descriptive study of BDD’s clinical features in this age group (29). They had a mean age of 14.7±2.5 (range=6–17) years, and 87.2% (n=34) were female. The mean age of BDD onset in this group was 11.7±2.7 (range=5–17) years. Among adults and adolescents combined, the most common areas of concern were the skin (e.g., acne or scarring; 69.0%; n=169), hair (55.7%; n=137), and nose (35.7%; n=87), although any body area could be the focus of concern. Over the course of their illness, subjects were concerned with 3.8±2.4 (range=1–13) body areas. The most common lifetime comorbid disorders were major depression (73.7%; n=182), social phobia (36.8%; n=91), and substance use disorders (31.6%; n=79).

Assessments

By use of a clinician-administered semistructured instrument (5) (Phillips KA, unpublished data), information was retrospectively obtained about the frequency of nonpsychiatric treatment sought and received in the following categories: dermatologic, surgical, other medical (e.g., ophthalmologic), dental, and paraprofessional (e.g., electrolysis). Whereas one surgical procedure was counted as one surgery, an entire course of treatment with a dentist (e.g., orthodontia) or a paraprofessional (e.g., a course of electrolysis) was counted as one treatment. An entire course of treatment received from a particular dermatologist or other nonsurgeon physician (e.g., internist, ophthalmologist) was also counted as one treatment because patients were often unable to recall specific, individual types of treatment (such as different types of oral or topical antibiotics) received from these physicians. Thus, frequencies of dermatologic and “other medical” treatment received represent the number of different physicians seen rather than the number of different types of treatment received. Information was also obtained on why treatment sought from a professional was not actually received.

Response to these treatments was assessed with the Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI) (30). Ratings of “much” or “very much” improved on the CGI were considered to indicate improvement; ratings of “much” or “very much” worse were considered worsening; and ratings of “minimally improved,” “unchanged,” or “minimally worse” constituted no change. (Early in the study, “moderate” or “marked” improvement was used instead of “much” or “very much” improved and was considered indicative of improvement.) From the beginning of the study, treatment response was assessed for overall response of BDD symptoms; later in the study, treatment outcome was also obtained specifically for the treated body part (i.e., whether the subject worried less about and was less distressed by the treated body part per se). Several other variables were added later during the study, such as the type of surgery received.

All subjects age 13 and older were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-P) (31), and those 12 and younger were administered the K-SADS–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) (32) to obtain data on demographic features and associated psychopathology. Because these instruments do not assess BDD, this disorder was diagnosed with a reliable semistructured SCID-like diagnostic instrument based on DSM-IV criteria (33). The semistructured instrument noted above obtained information on characteristics of BDD (e.g., age at onset). Current severity of BDD symptoms was assessed with the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder, a reliable and valid 12-item clinician-administered scale (34). Current delusionality of appearance-related beliefs was determined with the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale, a reliable and valid 7-item, semistructured clinician-administered scale (35).

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and means±standard deviations were determined; χ2 was used for categorical analyses. Pearson product-moment correlation was used to assess the relationship between selected variables. Data for adults and for children/adolescents are reported separately because findings specific to these age groups are of interest. Results are reported only for adults except where they are specifically indicated to pertain to children and adolescents. Because some variables (e.g., treatment outcome for the treated body part) were added later in the study, data are missing for some subjects.

Results

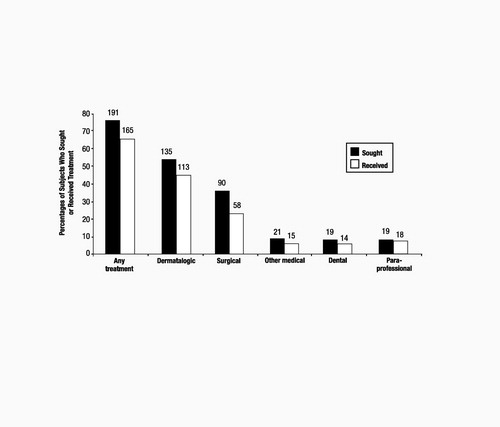

A majority of adults (76.4%; n=191) sought nonpsychiatric treatment for their perceived appearance flaws (Figure 1). A total of 785 nonpsychiatric treatments were sought, with 4.1±4.8 (range=1–35) treatments requested by those who sought such treatment; 38.2% (n=73) of these individuals requested treatment from more than one treatment category, most often both surgery and dermatologic treatment (63.0%; n=46).

Of the entire sample of adults, 66.0% (n=165) received nonpsychiatric treatment (Figure 1). Of those adults who sought such treatment, 86.4% (n=165) received it. A total of 484 nonpsychiatric treatments were received, with 2.9±3.0 (range=1–22) treatments received per adult who had such treatment; 63.0% (n=104) received more than one treatment, and 27.3% (n=45) received treatment from more than one category (e.g., both dermatologic and surgery).

Dermatologic treatment was most often received, by 45.2% of adults, with 2.4±2.6 (range=1–20) courses of treatment per adult who received dermatologic treatment. Antibiotics were most commonly prescribed, but treatments included minoxidil for perceived hair thinning and isotretinoin or dermabrasion for perceived acne. Subjects who had surgery (23.2% of adults) received 2.2±1.7 (range=1–9) surgical procedures. Rhinoplasty was the most common procedure (41.6% of all surgeries; n=32), followed by chin surgery (14.3%; n=11) and breast surgery (10.4%; n=8). The number of dental treatments (e.g., tooth filing or orthodontia) received was 2.5±4.5 (range=1–18). Other medical treatments were 1.4±.63 (range=1–3), and paraprofessional treatment was 1.4±0.7 (range=1–3). Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no significant association between the number of nonpsychiatric treatments sought or received and current BDD severity or delusionality, although there was a trend for subjects with more severe BDD symptoms to seek more nonpsychiatric treatment (r=0.12, P=0.09).

Approximately one-third (35.6%; n=267) of all requested treatments were not received: 53.5% of all requested surgeries, 30.0% of requested dental treatments, 27.6% of requested other medical treatments, 25.4% of requested dermatologic treatments, and 13.8% of requested paraprofessional treatments were not received. The most common reason for not receiving requested treatment was the physician’s considering the treatment unnecessary and not providing it (76.2%; n=170). Other reasons were cost (8.5%; n=19), fear of the procedure (3.6%; n=8), being dissuaded by someone other than the physician (3.1%; n=7), and miscellaneous reasons (8.5%; n=19).

Female and male adults were equally likely to seek nonpsychiatric treatment (77.9%, n=102, vs. 74.8%, n=89; χ2=0.33, df=1, P=0.57) and sought a similar number of treatments [3.6±5.3 vs. 2.6±3.5; t(227)=1.7, P=0.08]. Women and men were also equally likely to receive such treatment (70.2%, n=92 vs. 61.3%, n=73; χ2=2.2, df=1, P=0.14). However, women received a greater number of treatments than men [2.4±3.4 vs. 1.5±1.8; t(203)=2.6, P=0.009], which was accounted for by receiving more dermatologic treatment [1.4±2.6 vs. 0.8±1.2; t(188)=2.6, P=0.01]. Physicians were as likely to refuse treatments requested by women as by men (48.8%, n=83 vs. 51.2%, n=87; χ2=0.09, df=1, P=0.76). The refusal rate for women and men was similar for requested surgeries (45.9%, n=45 vs. 54.1%, n=53; χ2=0.65, df=1, P=0.42) and for all other types of treatment.

The most frequent treatment outcome was no change in overall BDD severity (72.0%, n=326 of treatments; Table 1). Regarding change in concern with the treated “defective” body part per se (rather than overall BDD severity), 61.4% (n=178) of treatments resulted in no change (Table 1). Although 23.1% (n=67) of treatments resulted in decreased concern with the treated body part (i.e., improvement), a majority (68.7%; n=46) of these treatments led to no improvement or worsening in overall BDD severity, generally because patients worried more about another body area, developed a new appearance concern, became more concerned about more minor imperfections in the treated area, or worried that an improved body part would become ugly again. Thus only 7.3% (n=21) of all treatments led to both a decrease in concern with the treated body part and overall improvement in BDD. There were no significant gender differences in outcome of overall BDD severity, including for surgery.

Regarding the children and adolescents, 41.0% (n=16) sought nonpsychiatric treatment for their perceived defect. All of the nine requested dermatologic treatments, two of three requested dental treatments, one of two requested other medical treatments, and one of two requested cosmetic surgeries were received. All of these treatments resulted in no change in concern with the treated body part or in severity of overall BDD symptoms.

Discussion

In this study a majority of adults and nearly half of children/adolescents received nonpsychiatric treatment, most often dermatologic and surgical, for their minimal or nonexistent appearance flaws. Our finding that 23% of patients had cosmetic surgery is similar to Veale’s finding that 26% of 50 BDD patients seen in a psychiatric setting had received surgery (6). Hollander et al. (4) reported an even higher rate of 40%. Whereas 48% of Veale’s subjects had seen either a cosmetic surgeon or a dermatologist (6), 72% of our subjects had sought and 60% had received treatment from one of these types of practitioners.

In this study the most common treatment outcome was no change in overall severity of BDD symptoms. Although we did not obtain ratings of satisfaction with treatment, our impression is that most patients considered this outcome unsatisfactory, which is consistent with Veale’s finding that 81% of 50 BDD patients seen in a psychiatric setting were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the outcome of nonpsychiatric medical consultation or operation (6). Some reports from the surgery literature indicate that patients with “minimal deformity” or “psychological problems” may respond well to surgery (11, 12, 14); however, it is unclear whether these patients have BDD. Our results suggest, in contrast, that surgery and other nonpsychiatric treatments rarely diminish BDD symptoms. Although concern with the treated body part improved in about one-quarter of cases, only 7.3% of all treatments led to both a decrease in concern with the treated body part and overall improvement in BDD. This finding is consistent with reports in the surgery and dermatology literature indicating that patients with BDD, and individuals resembling BDD patients, can be difficult to treat and are often dissatisfied with treatment (10, 13, 20, 21). They may request extensive work-ups, consult numerous physicians, pressure physicians to prescribe unsuitable and ineffective treatments, or take legal action against their physician (21, 23). As one dermatologist has stated, “The author knows of no more difficult patients to treat than those with body dysmorphic disorder” (23).

Although only a minority of patients experienced worsening of BDD symptoms with nonpsychiatric treatment, in some cases the outcome was extremely poor. For example, one man who had multiple ear surgeries became psychotic, suicidal, and violent each time the bandages were removed postsurgery, necessitating repeated emergency psychiatric hospitalization. A number of patients threatened to sue, or expressed fantasies of harming, their surgeon.

It is worth noting that physicians refused to provide more than one-quarter of all requested treatments. However, as has been noted in the surgery literature (13), some patients persistently pursue such treatment. One of our patients, for example, received a rhinoplasty after being refused treatment for various appearance concerns by 3 dermatologists, 3 dentists, and 16 plastic surgeons. Some patients harm themselves so the requested surgery will have to be done; one of our patients smashed his nose with a hammer so he could obtain a rhinoplasty. As has been reported by Veale (36), some patients even do their own surgery in an effort to improve their appearance, generally because they cannot afford to pay a surgeon or find one willing to perform the requested procedure. One of our patients, for example, cut off her nipples, and another attempted a rhinoplasty by replacing his nose cartilage with chicken cartilage.

Although some reports in the surgery literature warn against doing cosmetic surgery in men (16, 18), we found that men were no more likely to be refused surgery than women and that surgical outcomes were similar for women and men. Our finding that men were as likely as women to receive cosmetic surgery, in contrast to the general population (where men are less likely than women to have cosmetic surgery), raises the question of whether men with BDD are overrepresented among male cosmetic surgery patients. Indeed, one study that assessed the rate of BDD in patients seeking cosmetic surgery found that only 7% of women had BDD, whereas 33% of the men did (8).

Our study has a number of limitations. Data on nonpsychiatric treatment received was largely obtained retrospectively and was for the most part not verified (e.g., by medical record review), although in some cases family members or the referring physician corroborated the information provided. Interpretation of the outcome of dermatologic and other medical treatment is complicated by the fact that outcome was reported for an entire course of treatment rather than an individual treatment. Additional limitations are the lack of a control group and selection of the study sample from a research program specializing in BDD, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Perhaps most important, the study consisted of currently symptomatic patients who sought psychiatric evaluation after receiving nonpsychiatric treatment; this may have biased the results toward treatment failures because patients who do not improve with nonpsychiatric treatment may be more likely to remain symptomatic and seek psychiatric consultation. Studies that evaluate patients prospectively and address the other limitations of this study are needed.

In summary, these findings suggest that nonpsychiatric medical treatment usually does not improve BDD symptoms, thus supporting suggestions in the surgical and medical literature that such treatment should be avoided or approached with caution in this population. In contrast, emerging data suggest that psychiatric treatment (i.e., serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive-behavioral therapy) is often effective for BDD (28, 37, 38). However, the treatment response of this relatively common and severe disorder requires further investigation.

| Any Treatment n =453/290a | Surgery n =115/58 | Dermatologic n =265/178 | Dental n =34/29 | Other Medical n =17/9 | Paraprofessional n =22/16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | ||||||

| Overall BDD | 11.7 (53) | 17.4 (20) | 9.8 (26) | 14.7 (5) | 0.0 (0) | 9.1 (2) |

| Body part | 23.1 (67) | 34.5 (20) | 19.7 (35) | 20.7 (6) | 0.0 (0) | 37.5 (6) |

| Same | ||||||

| Overall BDD | 72.0 (326) | 58.3 (67) | 81.9 (217) | 29.4 (10) | 88.2 (15) | 77.3 (17) |

| Body part | 61.4 (178) | 48.3 (28) | 73.6 (131) | 13.8 (4) | 77.8 (7) | 50.0 (8) |

| Worse | ||||||

| Overall BDD | 16.3 (74) | 24.3 (28) | 8.3 (22) | 55.9 (19) | 11.8 (2) | 13.6 (3) |

| Body part | 15.5 (45) | 17.2 (10) | 6.7 (12) | 65.5 (19) | 22.2 (2) | 12.5 (2) |

Figure 1. Dermatologic, Surgical, Dental, and Other Nonpsychiatric Medical Treatment Sought and Received by 250 Adults With Body Dysmorphic Disorder

1 Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Riddle MA, et al: The relationship of obsessive-compulsive disorder to possible spectrum disorders: results from a family study. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:287–293Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Mayville S, Katz RC, Gipson MT, et al: Assessing the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in an ethnically diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies 1999; 8:357–362Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Phillips KA: Body dysmorphic disorder: the distress of imagined ugliness. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1138–1149Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Hollander E, Cohen LJ, Simeon D: Body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatric Annals 1993; 23:359–364Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Keck PE, et al: Body dysmorphic disorder: 30 cases of imagined ugliness. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:302–308Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Veale D, Boocock A, Gournay K, et al: Body dysmorphic disorder: a survey of fifty cases. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:196–201Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Pertschuk MJ, et al: Body image dissatisfaction and body dysmorphic disorder in 100 cosmetic surgery patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998; 101:1644–1649Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Ishigooka J, Iwao M, Suzuki M, et al: Demographic features of patients seeking cosmetic surgery. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 1998; 52:283–287Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Phillips KA, Dufresne RG Jr, Wilkel C, et al: Rate of body dysmorphic disorder in dermatology patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42:436–441Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Knorr NJ, Edgerton MT, Hoopes JE: The “insatiable” cosmetic surgery patient. Plast Reconstr Surg 1967; 40:285–289Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Edgerton MT, Jacobson WE, Meyer E: Surgical-psychiatric study of patients seeking plastic (cosmetic) surgery: ninety-eight consecutive cases with minimal deformity. Br J Plast Surg 1960; 13:136–145Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Edgerton MT, Langman MW, Pruzinsky T: Plastic surgery and psychotherapy in the treatment of 100 psychologically disturbed patients. Plastic Surgery and Psychotherapy 1991; 88:594–608Google Scholar

13 Fukuda O: Statistical analysis of dysmorphophobia in out-patient clinic. Japanese Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1977; 20:569–577Google Scholar

14 Hay GG: Psychiatric aspects of cosmetic nasal surgery. Br J Psychiatry 1970; 116:85–97Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Cunningham SJ, Bryant CJ, Manisali M, et al: Dysmorphophobia: recent developments of interest to the maxillofacial surgeon. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 1996; 34:368–374Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Ladee GA: Hypochondriacal Syndromes. Amsterdam, Netherlands, Elsevier, 1966Google Scholar

17 Phillips KA, McElroy SM, Lion JR: Plastic surgery and psychotherapy in the treatment of psychologically disturbed patients (letter). Plast Reconstruc Surg 1992; 90:333–334Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Wright MR: The male aesthetic patient. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1987; 113:724–727Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Zaidens SH: Dermatologic hypochondriasis: a form of schizophrenia. Psychosom Med 1950; 12:250–253Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Cotterill JA: Dermatological non-disease: a common and potentially fatal disturbance of cutaneous body image. Br J Dermatol 1981; 104:611–619Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Koblenzer CS: The dysmorphic syndrome. Arch Dermatol 1985; 121:780–784Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Hanes KR: Body dysmorphic disorder: an underestimated entity? (letter) Australian Journal of Dermatology 1995; 36:227–229Google Scholar

23 Cotterill JA: Body dysmorphic disorder. Dermatol Clin 1996; 14:457–463Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Cunningham SJ, Feinmann C: Psychological assessment of patients requesting orthognathic surgery and the relevance of body dysmorphic disorder. British Journal of Orthodontics 1998; 25:293–298Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Kells BE, Kime DL, Kennedy JG, et al: Dysmorphophobia: a case successfully treated using a multidisciplinary approach. Dental Update 1996; December:402–404Google Scholar

26 Phillips KA, Diaz S: Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:570–577Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, et al: A comparison of delusional and nondelusional body dysmorphic disorder in 100 cases. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 1994; 30:179–186Google Scholar

28 Phillips KA, Dwight MM, McElroy SL: Efficacy and safety of fluvoxamine in body dysmorphic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:165–171Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Albertini RS, Phillips KA: 33 cases of body dysmorphic disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:453–459Crossref, Google Scholar

30 National Institute of Mental Health: Special feature: rating scales and assessment instruments for use in pediatric psychopharmacology research. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 1985; 21:714–1124Google Scholar

31 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, et al: The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): I. history, rationale and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al: The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Phillips KA, Atala KD, Pope HG Jr: Diagnostic instruments for body dysmorphic disorder. Paper presented at American Psychiatric Association 148th Annual Meeting, Miami, Fl, 1995Google Scholar

34 Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, et al: A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:17–22Google Scholar

35 Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, et al: The Brown Assessments of Beliefs Scale: reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:102–108Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Veale D: Outcome of cosmetic surgery and “DIY” surgery in patients with body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatric Bulletin 2000; 24:218–221Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Hollander E, Allen A, Kwon J, et al: Clomipramine/desipramine crossover trial in body dysmorphic disorder: selective efficacy of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in imagined ugliness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:1033–1039Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Veale D, Gournay K, Dryden W, et al: Body dysmorphic disorder: a cognitive behavioral model and pilot randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:717–729Crossref, Google Scholar