Interactions Between Child and Parent Temperament and Child Behavior Problems

Abstract

Objective:

Few studies of temperament have tested goodness-of-fit theories of child behavior problems. In this study, we test the hypothesis that interactions between child and parent temperament dimensions predict levels of child psychopathology after controlling for the effects of these dimensions individually.

Methods:

Temperament and psychopathology were assessed in a total of 175 children (97 boys, 78 girls; mean age, 10.99 years; SD, 3.66 years) using composite scores from multiple informants of the Junior Temperament and Character Inventory and the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment. Parent temperament was assessed using the adult version of the Temperament and Character Inventory. Statistical analyses included multiple regression procedures to assess the contribution of child-parent temperament interactions after controlling for demographic variables, other types of child psychopathology, and the individual Temperament and Character Inventory and Junior Temperament and Character Inventory dimensions.

Results:

Interactions between child and parent temperament dimensions predicted higher levels of externalizing, internalizing, and attention problems over and above the effects of these dimensions alone. Among others, the combination of high child novelty seeking with high maternal novelty was associated with child attention problems, whereas the combination of high child harm avoidance and high father harm avoidance was associated with increased child internalizing problems. Many child temperament dimensions also exerted significant effects independently.

Conclusions:

The association between a child temperament trait and psychopathology can be dependent upon the temperament of parents. These data lend support to previous theories of the importance of goodness-of-fit.

(Reprinted with permission from Comprehensive Psychiatry 2006; 47:412–420)

1. INTRODUCTION

Temperament refers to individual differences in a person's emotional reactivity and regulation (1). Accumulating research has demonstrated associations between several specific temperament dimensions and child psychopathology (2, 3). In children and adolescents, high novelty seeking (NS) has been associated with externalizing problems (4) and disorders, including early onset antisocial behavior (5, 6) as well as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition conduct disorder (7). Measures of low persistence (P) have been linked to disruptive behavior (8) and attention problems (9, 10). In contrast, high levels of harm avoidance (HA) have been linked mainly with internalizing disorders in children and adolescents (4, 11, 12).

Fewer links have been found between parent personality and child psychopathology (13), although 1 study reported high neuroticism and low agreeableness in the fathers of children with comorbid disruptive behavior disorders (14). In contrast to the scant literature regarding parent temperament and personality, a larger body of research has shown important associations between child temperament, parenting, and child adjustment (15). The literature has also slowly begun to define the relations between parenting style and parent personality (16, 17). Low parent-child warmth and involvement, which bears some resemblance to the temperamental trait of low reward dependence (RD), have been shown to predict externalizing problems (18, 19). Parental overprotection, rejection, and decreased exposure opportunities (20) have been found in children and adolescents with internalizing disorders and may reflect variability in several temperament dimensions including HA, RD, and P (21).

Although informative, most previous studies of temperament and psychopathology have tested direct linear effects between a child or parent trait and psychopathology rather than interactional or “goodness-of-fit” models. This concept, which was developed by Thomas and Chess (22, 23), suggests that a particular trait or behavior in a child or parent may not be problematic in and of itself but leads to conflict and later behavior problems when there is a mismatch between the trait and the characteristics of a particular environment. Moreover, what literature exists in this area is inconsistent. Some evidence for specific child-parent temperament interactions (24) has been reported in predicting secure attachment, whereas other studies of infants (25) and handicapped children (26) have found little evidence that such interactions are associated with greater behavior problems.

This study tested the goodness-of-fit hypothesis using established temperament taxonomy with consistent dimensions across child and adult age groups. Our main hypothesis was that the relations between many of the previously mentioned child temperament traits and psychopathology would be dependent on levels of these same traits in parents. For example, although high NS in a child may predict externalizing problems, the combination of both a high-NS child and a high-NS parent was predicted to result in an even higher degree of disturbance than would be expected from each dimension independently. Based on the work previously described, the specific interaction terms tested in this study included (1) child NS with parent NS, HA, RD, and P; (2) child HA with parent NS, HA, RD, and P; (3) child RD with parent RD; and (4) child P with parent NS and P. This is, to our knowledge, the first study that tested the “fit” of specific parent and child temperamental dimensions as it relates to levels of childhood psychopathology in a school aged sample.

2. METHOD

2.1. Subjects

Participants came from a family study conducted in the northeastern United States that was designed to examine the genetic and environmental contributions to attention and aggression (27). Potential families were recruited from local pediatricians and psychiatrists in a university-based outpatient clinic based on a review of clinical records. Local newspaper advertisements and posters were also used. Families were initially screened over the telephone for the following demographic inclusion criteria: (1) proband child between the ages of 6 and 18 years; (2) proband child living with at least 1 biologic parent; and (3) proband child with at least 1 sibling between the ages of 6 and 18 years.

A total of 206 families participated in the study. The present investigation used 1 randomly selected sibling from each family as subjects rather than the proband. This was done because the proband selection criteria excluded subjects with intermediate levels of both aggression and attention problems and focused on selecting probands with more extreme combinations. As a result, the normal distribution of these and other related scales was disrupted and thought not to be optimal in analyses comparing these problems with continuously distributed temperamental traits. The randomly selected sibling was not subject to any of the restrictions imposed on probands. Parents of subjects and all subjects themselves older than 11 years signed a statement of informed consent.

2.2. Child psychopathology assessment

The following measures were used to form composite measures of child psychopathology and come from the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) (28).

2.2.1. Child behavior checklist

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is a standardized and widely used instrument in which parents report the frequency of 120 problem behaviors exhibited by their child in the past 6 months. To preserve power, only 3 scales were selected as dependent variables based on the hypotheses of the study. These included the overall externalizing and internalizing scales and the attention problems subscale, which is not included in either externalizing or internalizing problems. There were 182 mother-rated CBCLs and 90 rated by the father.

2.2.2. Youth self-report form

The Youth Self-Report Form, which follows a similar format as the CBCL, allows for the self-report of subjects and has shown to be valuable adjunct to ratings obtained from parents. It can be used for participants aged 11 years and older and was obtained for 93 of the 101 age-eligible subjects.

2.2.3. Teacher report form

Subjects were encouraged to submit the Teacher Report Form to the teacher who the family believed knew the subject the best. Sixty-six Teacher Report Forms were available for data analysis.

2.2.4. Test observation form

The Test Observation Form (29) was added during the course of subject recruitment as an additional source of data. As this scale was under development during the course of this study, some earlier versions were used and scored according to the most recent 2004 scoring algorithms (30). The raters for these scales were trained bachelor-level research assistants supervised by a licensed child psychologist and board-certified child psychiatrist. A total of 144 were completed.

2.2.5. Composite measure

Because of substantial differences that have been found between ratings from different informants (31), we computed a composite measure of each child's level of externalizing, internalizing, and attention problems. Raw scores for these scales were first converted to z scores. The composite z score was then computed by obtaining the mean of all available informants. A composite score was computed only if there were at least 2 informants. All 5 informants were available for 7 subjects, 4 for 52 subjects, 3 for 68 subjects, and 2 for 58 subjects, whereas 21 subjects were excluded because there was no more than 1 informant of child psychopathology. There were no significant correlations between the number of informants and any of the 3 composite measures of behavior problems. Similarly, there were no significant differences in the mother-rated CBCLs in internalizing, externalizing, or attention problems between subjects who were excluded from the analysis because of a lack of informants and those who were included.

2.3. Temperament assessment

Temperament was assessed using the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) (32, 33) and its downward extension, the Junior Temperament and Character Inventory (JTCI), which has shown good reliability and validity (34, 35). The JTCI consists of 108 statements that the respondent rates as true or false based on how the person usually acts and feels. Parent temperament and character were measured using a 125-item short version of the TCI that has established reliability and validity (32).

Of the 4 temperament dimensions, NS describes a tendency to seek out stimulation and includes measures of impulsivity, extravagance, and disorderliness. The HA dimension refers to the degree a person inhibits behavior and contains elements of worry, shyness, and fatigability. Reward dependence (RD) is defined as the tendency to maintain behaviors and includes the degree of sentimentality, attachment, and dependence. Persistence (P) reflects the ability of an individual to persevere despite obstacles or frustration. The temperament dimensions of the JTCI and TCI are the same. The 3 character dimensions were not used for these analyses.

2.3.1. Composite measures of child temperament

Similar to ratings obtained for child psychopathology, we attempted to increase validity by creating a composite measure of child temperament by averaging the z scores of the 4 temperament scales from 4 possible informants (mother, father, self, and teacher). Here, we required at least 1 informant for a valid score. Of the 206 initially participating families, 1 informant (usually mother) was obtained for 37 subjects, 2 informants for 87 subjects, 3 for 67 subjects, 4 for 7 subjects, and 8 were excluded because there were no informants of child temperament. Again, there were no significant correlations between the number of informants and the 4 composite temperament dimensions. In analyses similar to those used for missing composite behavioral ratings, we compared mother-rated JTCIs between subjects included vs excluded from the study and found that of the 4 temperament scales, RD was higher in excluded subjects (8.0 vs 6.2; F[1,188] = 5.36; P < .05). Parent temperament was assessed through self-report only. In total, final data, which required valid data for child psychopathology, child temperament, and parent temperament were obtained for 175 children (97 boys and 78 girls) for analyses between child and mother temperament and 88 children (46 boys and 42 girls) for analyses of child and father temperament. The mean age of the child was 10.99 years (SD, 3.66). Age, sex distribution, and socioeconomic status (SES) (AB Hollingshead, unpublished data, 1975) similarly did not differ between those individuals with and without complete data except for higher SES in the families where child and father data were obtained, compared with families with missing child-father data (6.9 vs 6.1; t = 2.56; df = 201; P < .05).

2.4. Data analysis

Multiple regression procedures were used to test the contribution of particular interactions between child-parent temperament after controlling for the effects of demographics, child temperament alone, and parent temperament alone. Three regression models were created with the composite externalizing, internalizing, and attention problems scores each as the dependent variable. Potential predictors for each regression included the 3 demographic variables (age, sex, and SES), the 4 child temperament dimensions (composite) and the TCI for the parent (self-report), and the particular interaction terms of interest. Regressions for each parent were conducted separately. Because there are substantial correlations among CBCL scales (36), these were also included as potential covariates. From our own data, the correlation between internalizing and externalizing problems was .51 (P < .001). All predictors were entered simultaneously into the regression model to test the contribution of each variable, controlling for all others. Standardized β coefficients are presented as well as squared semipartial correlations to calculate the amount of variance attributed to each independent variable. Because interaction terms in regression models do not reveal the nature and direction of the interaction, those interactions found significant were investigated graphically by creating groups of children with high and low scores on a particular dimension based on a mean split (z score greater or less than 0) and plotting them against 2 groups based on the parent temperament dimension. If this procedure did not reveal the nature of the interaction, quartile splits were used. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were also used to examine differences in levels in child psychopathology among groups identified from the regressions.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Temperament correlations

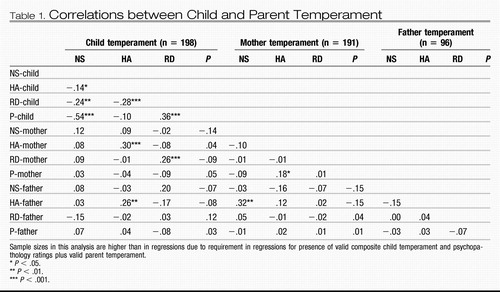

The correlations between child, mother, and father temperament are shown in Table 1. In general, there were significant correlations among the child temperament dimensions, between child and both mother and father HA and between child and mother RD. The only significant temperament correlation between parents was between mother NS and father HA (r = .32; P < .01).

|

Table 1. Correlations between Child and Parent Temperament

3.2. Child and maternal temperament

3.2.1. Externalizing problems

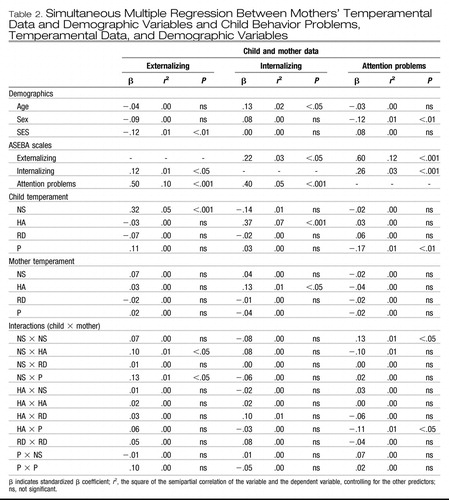

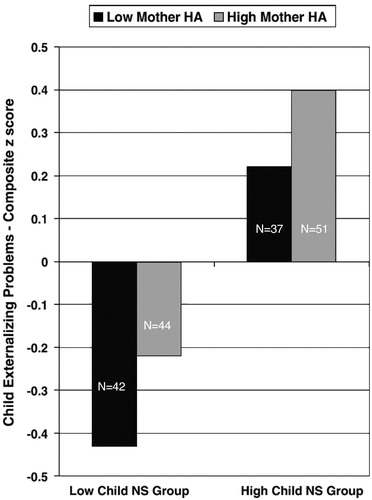

As can be seen in Table 2, lower SES and higher child NS predicted child externalizing scores. There were no significant maternal temperament predictors found as main effects; however, the main effect of higher child NS relating to higher externalizing problems was highly significant (β = .32; P < .001). The child NS × mother HA interaction (Fig. 1) and the child NS × mother P interaction were also significant, such that the effect of child NS on externalizing problems was dependent on the level of maternal HA and P. Follow-up ANOVAs revealed that among low- but not high-NS children, high maternal HA was associated with higher child externalizing scores (F[1,84] = 4.29; P < .05). We did not find statistically significant comparisons among the child NS × mother P groups, in part because certain combinations of child and mother temperaments were quite rare. For example, of the quartile of 42 children with the lowest NS scores, 35 had mothers in the top 50% of P scores. Of the 41 children with the highest NS scores, the trend was the opposite (34 mothers in the lower 50% of P scores). As expected, other Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) scales were significant covariates in each regression model.

|

Table 2. Simultaneous Multiple Regression Between Mothers' Temperamental Data and Demographic Variables and Child Behavior Problems, Temperamental Data, and Demographic Variables

Interactions from simultaneous multiple regressions in which child temperament × parent temperament was entered simultaneously with other demographic, child temperament, parent temperament, and interaction terms (see Table 1). Child NS × Mother HA β = .10, P < .05. Follow-up ANOVAs revealed that among low-NS children, higher maternal HA was associated with higher child externalizing problems (F[1,84] = 4.29; P < .05). No such effect was found among high-NS children (F[1,86] = 1.13; P = not significant).

3.2.2. Internalizing problems

Higher internalizing problems were positively associated with age. Among the temperament variables, higher levels of child HA were predictive of increased internalizing scores as was maternal HA, each acting independently. No child × mother temperament interactions were found to be statistically significant.

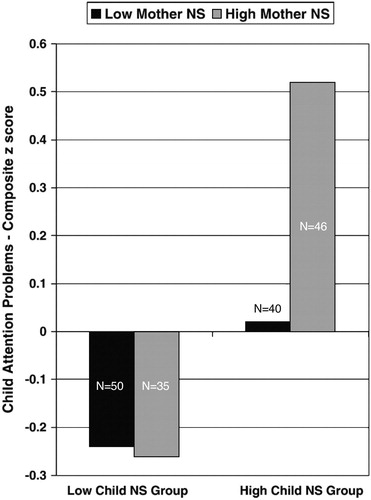

3.2.3. Attention problems

Attention problems were higher in boys. Lower child P was also found to significantly predict higher attention problems. Again, no maternal temperament dimensions were found to be significant alone, but the child NS × mother NS interaction was significant as was child HA × mother P interaction. Subsequent ANOVAs revealed that mean attention problems scores were no different among low NS children between high- and low-NS mothers, whereas for high NS children, high maternal NS was associated with significantly higher child attention problems (F[1,84] = 9.46; P < .01) as shown in Fig. 2. For the child HA × mother P interaction, follow-up ANOVAs were non significant.

Interactions from simultaneous multiple regressions in which child temperament × parent temperament was entered simultaneously with other demographic, child temperament, parent temperament, and interaction terms (see Table 1). Child NS × mother NS β = .13, P < .05. Follow-up ANOVAs revealed that among high-NS children, higher maternal NS was associated with higher child attention problems (F[1,84] = 9.46; P < .01). No such effect was found among low-NS children (F[1,83] = 0.03; P = not significant).

Because an effect of sex was found, we analyzed the data separately for boys and girls. For boys, child P and the child HA × mother P interaction remained significant; however, the child NS × mother NS did not because of loss of sample size (the standardized βs were nearly identical). For girls, higher attention problems were found not to be related to lower child P with higher child NS just missing statistical significance (β = .23, P = .058). Here, the child NS × mother NS interaction remained significant (β = .30, P < .05), whereas the HA × P interaction was non significant (β = −.06, P = non significant).

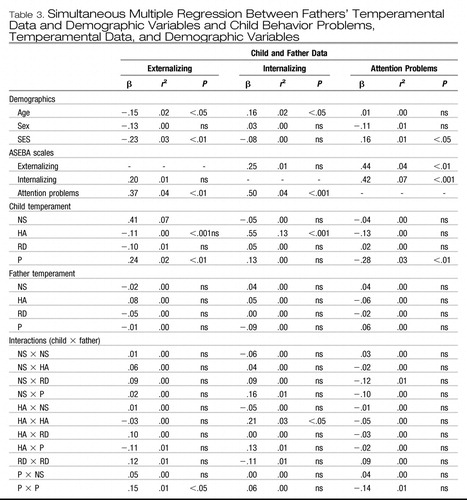

3.3. Child and paternal temperament

3.3.1. Externalizing problems

Corresponding analyses were conducted using paternal rather than maternal temperament as shown in Table 3. Because fewer fathers participated in the study, the sample size was reduced (n = 88 for father-child pairs), and these results should be considered preliminary. Once again, there were significant intercorrelations between the 3 ASEBA scales that remained as significant covariates in the regression models. Nevertheless, several temperament variables alone and in interaction also remained significant as independent predictors. Significant temperamental predictors of child externalizing scores included lower age and SES and 2 of the 4 child temperament measures: higher NS and higher P. The higher P may represent a suppressor effect as the bivariate correlation between P and externalizing problems was significant and negative (r = −.38; P < .001). Furthermore, the significant child P × father P interaction indicated that low externalizing scores were associated with the combination of high child and father persistence, whereas the association between low child P and externalizing problems was less dependent upon father P levels. The ANOVAs comparing child externalizing scores among children with high P scores between fathers with low or high P approached statistical significance (F[1, 42] = 3.24, P = .08) again because of the fact that particular child-parent combinations (in this case, high-P children with low-P fathers) were very uncommon (n = 5).

|

Table 3. Simultaneous Multiple Regression Between Fathers' Temperamental Data and Demographic Variables and Child Behavior Problems, Temperamental Data, and Demographic Variables

3.3.2. Internalizing problems

For internalizing problems, the significant predictors included higher age and higher child HA. Again, no paternal temperament dimensions were significant on their own; however, the child HA × father HA interaction remained significant despite the strong main effect of child HA. Graphing the HA × HA result showed high child internalizing scores associated with the particular combination of a high-HA child and a high-HA father, although specific ANOVA comparison just missed significance because of small sample size (F[1,15] = 4.05; P = .06).

3.3.3. Attention problems

For child attention problems, the only significant predictors were SES (again a possible suppressor effect) and, once again, lower child P. No demographic, father temperament, or child × father temperament interactions were found to be significant.

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined the “goodness of fit” hypothesis with regard to child-parent temperament and child psychopathology. The results showed that the interaction between child and parent temperament dimensions were significant additional predictors of childhood psychopathology even after controlling for the effects of the same dimensions acting independently. The effect of child temperament upon child psychopathology can be dependent on parent temperament, and the effect of parent temperament upon child psychopathology can be dependent on child temperament. The findings support previous hypotheses that stress the importance of looking beyond simple linear relationships between a particular temperament trait and psychopathology. Similarly, the associations between internalizing and externalizing problems were diminished after accounting for temperament both for main effects and interactions.

Different interactions were related to different types of problems. Moreover, differential effects were found between mother and father temperament. For externalizing problems, several interactions were found, most of which involved the dimensions of NS, HA, and persistence. Although the risk-taking and exploratory features of NS are often highlighted, there are also several items that could be referred to as self-regulatory skills, such as limiting impulsivity and being able to delay gratification, some of which are also involved in persistence. Prospective studies have documented associations with other measures of disinhibition or being “undercontrolled” with both externalizing and internalizing problems in later life (8, 37). It is possible that similar self-regulatory deficits in parents contribute to the increased levels of child-parent conflict that have been linked to child behavior problems (38–40). The association between child temperament and adjustment has also been hypothesized to be mediated through mismatches of behavioral expectations with peer or parent demands (41) or through disrupted attachment patterns (24, 42). Additional studies are planned with this and other samples to test whether the association between these interactions and child psychopathology are mediated by specific parenting or family environment factors. The child P × father P interaction showed particularly low externalizing scores with the combination of a high-P child and high-P father. In a clinical sample, this result could have been missed and underscores the importance of looking at nonclinical populations.

For internalizing problems, the expected importance of the child HA × parent HA interaction was seen in fathers. It is possible that high levels of HA in fathers underlie the increased overprotection found in some parents of anxious children (20). These results suggest that a father's level of inhibition or anxiety may play an important role in the development of internalizing symptoms in their children, especially in those with similar predispositions. Caution should be used with this finding because post hoc comparisons were not significant, although there was a significant interaction found in the regression. Replication using a larger sample with efforts directed at obtaining hard-to-find child/parent temperament combinations are advised. Longitudinal studies would also be helpful in differentiating the degree to which high father HA may also be a response to having a more anxiety-prone child. The specific role of fathers in the development of internalizing disorders has received little specific attention and appears to warrant further study. It is puzzling that similar interactions were not found in mothers, although maternal HA was independently predictive of child internalizing problems.

For attention problems, some evidence of a sex effect was also found with problems relating to low child P in boys and (at the trend level) higher child NS in girls. Furthermore, different interactions were found between mothers and their male vs female children. Looking at boys and girls combined, the child NS × mother NS interaction suggested that the combination of a high-NS child and high-NS mother may be particularly problematic with regard to child attention problems.

The importance of specific temperament interactions in these results should not diminish the robust findings where a child trait exerted an individual effect acting alone. Child NS, HA, and P each significantly predicted levels of psychopathology for different types of behavior problems. These results do not contradict the goodness-of-fit hypothesis except in its most literal form. Rather, our findings from this study suggest a more complicated picture where certain temperamental traits in children can exert an effect both independently and in interaction with other traits. Interestingly, it appeared that child temperamental traits could exert strong independent effects on their own, whereas levels of parent temperamental traits, with the exception of maternal HA and child internalizing problems, were significant only in their interaction with child traits.

Similarly, the interactions do not contradict the importance of the genetic influence of these temperamental traits (43) or their shared genes with certain psychiatric disorders (44). Because parents influence both the genes and environments of their offspring, effects of what appear to be important environmental variables may, at least in part, be due to genetic influences. For example, it is likely that risk genes for parent attention problems, independent from any links to temperament, are inherited and contribute to child attention problems. This effect could then diminish the perceived influence of temperamental interactions. Although we cannot completely eliminate the possibility of such genotype-environment interaction from our results, we would expect that if it were inherited genetic risk that was accounting for the associations with psychopathology, then this would be at least partially detected in the main effects of child or parent temperament on psychopathology rather than the interactions that controlled for these main effects. Ideally, as pointed out by Rutter and colleagues (45), the impact of environmental factors are best evaluated within a genetically informative design such as a twin or adoption study.

One limitation of this study concerns the content overlap between items on the ASEBA scales used to assess psychopathology and items on the TCI and JTCI used to assess temperament. Although the real vs tautological distinction between temperament and psychopathology remains an important issue both methodologically and theoretically, this association has been found to be preserved even when overlapping items are removed (46). Furthermore, any potential overlap does not diminish the finding of the importance of interactions, namely, how the effect of a child trait or symptom is dependent on corresponding traits or symptoms in parents. Another question concerns the assessment of temperament in older children. Although school-age children in comparison with infants or toddlers have certainly had more time to have their temperament modified by external factors, research has shown that the stability and heritability coefficients of many temperamental traits increase through childhood (47). Finally, this study was performed with an ethnically homogenous group from the northeastern United States. As such, the generalizability of these findings to other cultural groups remains to be determined.

In summary, these findings suggest that more extreme levels of particular temperamental traits may not be problematic in and of themselves but can lead to certain types of behavioral problems when paired with more extreme levels of other temperamental traits in parents. Clinically, the results support the necessity of evaluating the full family context, including fathers, of child psychiatric symptoms. Concentrating on particular interactions between child and parent temperament rather than just on the child alone may well be more easily accepted by child patients and viewed as less pathologizing. It is to be hoped that additional research confirm whether these interactions actually precede the emergence of significant behavioral problems and are moderated by important parenting and family characteristics. If so, interventions directed at these moderating variables could help reduce the association between particular temperamental interactions and various types of maladaptive behavior.

[1] Goldsmith HH, Buss AH, Plomin R, Rothbart MK, Thomas A, Chess S, et al. Roundtable: what is temperament? Four approaches. Child Dev 1987;58:505–29. Crossref, Google Scholar

[2] Shiner R, Caspi A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: measurement, development, and consequences. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003;44(1):2–32. Crossref, Google Scholar

[3] Rettew DC, McKee L. Temperament and its role in developmental psychopathology. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2005;13(1):14–27. Crossref, Google Scholar

[4] Kuo PH, Chih YC, Soong WT, Yang HJ, Chen WJ. Assessing personality features and their relations with behavioral problems in adolescents: tridimensional personality questionnaire and junior Eysenck personality questionnaire. Compr Psychiatry 2004;45(1): 20–8. Crossref, Google Scholar

[5] Tremblay RE, Pihl RO, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL. Predicting early onset of male antisocial behavior from preschool behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51(9):732–9. Crossref, Google Scholar

[6] Wills TA, DuHamel K, Vaccaro D. Activity and mood temperament as predictors of adolescent substance use: test of a self-regulation mediational model. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;68(5):901–16. Crossref, Google Scholar

[7] Schmeck K, Poustka F. Temperament and disruptive behavior disorders. Psychopathology 2001;34(3):159–63. Crossref, Google Scholar

[8] Caspi A. The child is father of the man: personality continuities from childhood to adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000;78(1):158–72. Crossref, Google Scholar

[9] Hoza B, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Kipp H, Owens JS. Academic task persistence of normally achieving ADHD and control boys: performance, self-evaluations, and attributions. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69(2):271–83. Crossref, Google Scholar

[10] Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Longitudinal predictors of behavioural adjustment in pre-adolescent children. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001;35(3):297–307. Crossref, Google Scholar

[11] Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, et al. A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993;32(4):814–21. Crossref, Google Scholar

[12] Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38(8):1008–15. Crossref, Google Scholar

[13] Warner MB, Morey LC, Finch JF, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, et al. The longitudinal relationship of personality traits and disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 2004;113(2):217–27. Crossref, Google Scholar

[14] Nigg JT, Hinshaw SP. Parent personality traits and psychopathology associated with antisocial behaviors in childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1998; 39(2):145–59. Crossref, Google Scholar

[15] Bates JE, McFadyen-Ketchum S. Temperament and parent-child relations as interacting factors in children's behavioral adjustment. In: Molfese VJ, Molfese DL editors. Temperament and personality development across the life span. Mahway (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. p. 141–76. Google Scholar

[16] Clark LA, Kochanska G, Ready R. Mothers' personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000;79(2):274–85. Crossref, Google Scholar

[17] Hooley JM, Hiller JB. Personality and expressed emotion. J Abnorm Psychol 2000;109(1):40–4. Crossref, Google Scholar

[18] Bates JE, Bayles K, Bennett DS, Ridge B, Brown MM, Pepler D, et al. Origins of externalizing behavior problems at eight years of age. In: Pepler D, Rubin K, editors. Development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hillsdale (NJ): Erlbaum; 1991. p. 93–120. Google Scholar

[19] Olson SL, Bates JE, Sandy JM, Lanthier R. Early developmental precursors of externalizing behavior in middle childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2000;28(2):119–33. Crossref, Google Scholar

[20] Lieb R, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, Fuetsch M, Stein MB, Merikangas KR. Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: a prospective-longitudinal community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57(9):859–66. Crossref, Google Scholar

[21] Arrindell WA, Emmelkamp PM, Monsma A, Brilman E. The role of perceived parental rearing practices in the aetiology of phobic disorders: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1983;143:183–7. Crossref, Google Scholar

[22] Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and development. New York: Bruner/Mazel; 1977. Google Scholar

[23] Thomas A, Chess S. Genesis and evolution of behavioral disorders: from infancy to early adult life. Am J Psychiatry 1984;141(1):1–9. Crossref, Google Scholar

[24] Mangelsdorf S, Gunnar M, Kestenbaum R, Lang S, andreas D. Infant proneness-to-distress temperament, maternal personality, and mother-infant attachment: associations and goodness of fit. Child Dev 1990;61:820–31. Crossref, Google Scholar

[25] Sprunger L, Boyce WT, Gaines JA. Family-infant congruence: routines and rhythmicity in family adaptation to a young infant. Child Dev 1985;56:564–72. Crossref, Google Scholar

[26] Wallander JL, Hubert NC, Varni JW. Child and maternal temperament characteristics, goodness of fit, and adjustment in physically handicapped children. J Clin Child Psychol 1988;17:336–44. Crossref, Google Scholar

[27] Hudziak JJ, Copeland W, Stanger C, Wadsworth M. Screening for DSM-IV externalizing disorders with the child behavior checklist: a receiver-operating characteristic analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 2003;42(3):357–63. Google Scholar

[28] Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18. Burlington (Vt): Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. Google Scholar

[29] McConaughy SH, Achenbach TM, Gent CL. Multiaxial empirically based assessment: parent, teacher, observational, cognitive, and personality correlates of child behavior profile types for 6- to 11-year-old boys. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1988;16(5):485–509. Crossref, Google Scholar

[30] McConaughy SH, Achenbach TM. Manual for the test observation form for ages 2–18. Burlington (Vt): University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2004. Google Scholar

[31] Goldsmith HH, Rieser-Danner LA, Briggs S. Evaluating convergent and discriminant validity of temperament questionnaires for preschoolers, toddlers, and infants. Dev Psychol 1991;27:566–79. Crossref, Google Scholar

[32] Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): a guide to its development and use. St. Louis (Mo): Center for Psychobiology of Personality, Washington University; 1994. Google Scholar

[33] Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50(12):975–90. Crossref, Google Scholar

[34] Luby JL, Svrakic DM, McCallum K, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. The Junior Temperament and Character Inventory: preliminary validation of a child self-report measure. Psychol Rep 1999;84(3 Pt 2): 1127–38. Google Scholar

[35] Lyoo IK, Han CH, Lee SJ, Yune SK, Ha JH, Chung SJ, et al. The reliability and validity of the Junior Temperament and Character Inventory. Compr Psychiatry 2004;45(2):121–8. Crossref, Google Scholar

[36] Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington (Vt): University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. Google Scholar

[37] Silva PA, Stanton W. From child to adult: the Dunedin Study. Oxford (England): Oxford University Press; 1996. Google Scholar

[38] Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono W. Parent-child conflict and the comorbidity among childhood externalizing disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(5):505–13. Crossref, Google Scholar

[39] Pike A, McGuire S, Hetherington ME, Reiss D, Plomin R. Family environment and adolescent depressive and antisocial behavior: a multivariate genetic analysis. Dev Psychol 1996;32(4):590–604. Crossref, Google Scholar

[40] Johnston C. Parent characteristics and parent-child interactions in families of nonproblem children and ADHD children with higher and lower levels of oppositional-defiant behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1996;24(1):85–104. Crossref, Google Scholar

[41] Talwar R, Nitz K, Lerner RM. Relations among early adolescent temperament, parent and peer demands, and adjustment: a test of the goodness of fit model. J Adolesc 1990;13(3):279–98. Crossref, Google Scholar

[42] Seifer R, Sameroff AJ, Barrett LC, Krafchuk E. Infant temperament measured by multiple observations and mother report. Child Dev 1994;65:1478–90. Crossref, Google Scholar

[43] Keller MC, Coventry WL, Heath AC, Martin NG. Widespread evidence for non-additive genetic variation in Cloninger's and Eysenck's personality dimensions using a twin plus sibling design. Behav Genet 2005;35:707–21. Crossref, Google Scholar

[44] Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental sources of covariation between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(9):1581–7. Crossref, Google Scholar

[45] Rutter M, Dunn J, Plomin R, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Maughan B, et al. Integrating nature and nurture: implications of person-environment correlations and interactions for developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 1997;9:335–64. Crossref, Google Scholar

[46] Lemery KS, Essex MJ, Smider NA. Revealing the relation between temperament and behavior problem symptoms by eliminating measurement confounding: expert ratings and factor analyses. Child Dev 2002;73(3):867–82. Crossref, Google Scholar

[47] Nigg JT, Goldsmith HH. Developmental psychopathology, personality, and temperament: reflections on recent behavioral genetics research. Hum Biol 1998;70(2):387–412. Google Scholar