From the Guest Editor

The concepts of temperament and personality are ancient in psychiatry, extending back to the beginning of history in ancient Greek writings. Temperament originally referred to those aspects of personality that are innate, rather than learned, whereas character was considered to be what we made of ourselves intentionally. Temperament is the emotional core of personality that is moderately stable throughout life, whereas character reflects a person's goals and values as they develop over the lifespan. However, research has shown that nature and nurture are always interactive in influencing all aspects of personality despite these differences in content and development.

Temperaments were also originally thought to be traits that were either present or absent, as was once suggested for the categories and clusters of personality disorder in DSM-III to DSM-IV. Once again research has demonstrated that personality traits vary quantitatively and occur in all possible combinations. The proposed revision of personality disorders for DSM-V continues to struggle with these questions of types and traits.

Many clinicians have assumed in the past that personality and its disorders are fixed traits and do not respond to treatment. Such expectations can lead to neglect of personality assessment as a self-fulfilling prophecy that reduces hope. A growing body of data has shown reductions in drop-out, relapse, and recurrence, as well as increases in well-being when the positive adaptive potential of a person is focused on in the assessment of temperament and other aspects of personality (1).

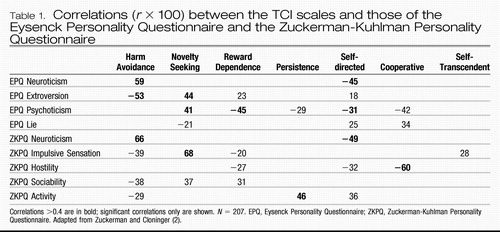

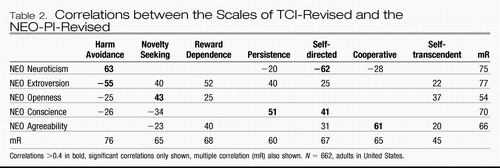

This issue of Focus concentrates on the use of the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) to evaluate these fundamental questions about the effects of nature and nurture on the development of personality and psychopathology in a way that is useful for the promotion of health and well-being in clinical practice. The TCI measures both adaptive and maladaptive personality traits, which makes it particularly useful for evaluating alternative approaches to personality assessment and for differential diagnosis and treatment planning in general. Personality traits can be described in many different ways, and unfortunately the same name is often used to label different combinations of traits. For example, Eysenck distinguished only neuroticism, extraversion-introversion, and psychoticism, and these traits are closely related to three proposed for DSM-V (negative emotionality, introversion, and antagonism). The TCI measures were developed to better measure individual differences in psychobiological processes within the person that shape learning and development. They are compared with those of Eysenck and Zuckerman (2) in Table 1 and to those of Costa and McCrae in Table 2 (3). What is important for a clinician to know is that the same name does not always mean the same thing: different tests with the same name measure different things, as seen by examining the TCI correlates of the neuroticism measures of Eysenck, Zuckerman, and Costa. Fortunately, the TCI provides a system of measurement that encompasses other tests and has predictive validity as good as or better than that of other available tests (4).

|

Table 1. Correlations (r × 100) between the TCI scales and those of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire and the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire

|

Table 2. Correlations between the Scales of TCI-Revised and the NEO-PI-Revised

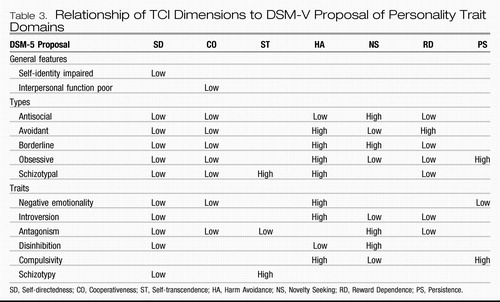

In addition, the constructs in the TCI provide a way to evaluate the components proposed for DSM-V (http://www.dsm5.org) (Table 3). The DSM-V Work Group proposal represents a significant advance in the assessment and treatment of personality disorders because it describes the core elements of healthy personality functioning, which are deficient in all personality disorders. The TCI character traits directly measure the features that distinguish healthy personality function from features common to all personality disorders, which are self-directedness and cooperativeness (5). The recent proposal of the APA Work Group on Personality for DSM-V explicitly described the adequacy of the functioning of the self as “identity integration, integrity of self-concept, and Self-directedness.” It described the adequacy of interpersonal functioning as “empathy, intimacy and Cooperativeness, and complexity and integration of representations of others.”

|

Table 3. Relationship of TCI Dimensions to DSM-V Proposal of Personality Trait Domains

The TCI temperament measures distinguish the types and traits proposed for DSM-V as well (Table 3). The use of personality traits and core character features will require an adjustment in thinking by many psychiatrists. The adjustment is expected to be difficult and can be expected to improve care in a practical way that we will describe in this issue. However, our focus here is not to describe or evaluate the preliminary DSM-V proposal in detail; rather it is to update clinicians on fundamental questions about nature and nurture in temperament and personality and about the clinical effectiveness of a person-centered approach to diagnosis and treatment, whether your practice involves mainly medication management or a particular form of psychotherapy.

1 Cloninger CR: The science of well-being: an integrated approach to mental health and its disorders. World Psychiatry 2006; 5:71–76 Google Scholar

2 Zuckerman M, Cloninger CR: Relationship between Cloninger's, Zuckerman's, and Eysenck's dimensions of personality. Pers Individual Differ 1996; 21:283–285 Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Cloninger CR: Personality as a dynamic psychobiological system, in Dimensional Models of Personality Disorders: Refining the Research Agenda for DSM-V. Edited by Widiger TA, Simonsen E, Sirovatka PJ, Regier DA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2006, pp 73–76 Google Scholar

4 Grucza RA, Goldberg LR: The comparative validity of 11 modern personality inventories: predictions of behavioral acts, informant reports, and clinical indicators. J Pers Assess 2007; 89:167–187 Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Cloninger CR: A practical way to diagnose personality disorder: a proposal. J Pers Disord 2000; 14:99–108 Crossref, Google Scholar