Strategies for the Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behavior

Abstract

This article discusses research-informed strategies for predicting and treating suicidal behavior. One of the most important approaches is to provide training to health professionals in recognizing and treating depression aggressively. An awareness of risk factors, such as certain psychiatric disorders, past suicide attempts, age, gender, other illnesses, and access to means, is essential to these strategies. Levels of treatment that include proper prescription of medication for depression, paired with psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavior therapy, and extensive communication between patient and health professional may be the best predictors of remission. Intervention plans should also include community education, simple interventions, and treatment of the underlying psychiatric disorders, including the use of lithium and electroconvulsive therapy.

CLINICAL CONTEXT

CURRENT STATISTICS ABOUT DEATH BY SUICIDE

In 2005, the year of the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics, there were approximately 32,000 suicides in the United States. This is the equivalent of 89 suicides per day or one suicide every 16 minutes. The number has fluctuated for the past 6 years, showing a significant increase in 2004 and a small decrease in 2005.

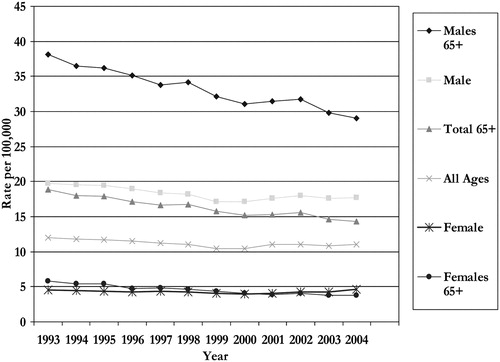

The unnecessary loss of life to suicide is a staggering problem for the U.S. population. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people 25–34 years of age and the third leading cause of death for those 15–24 years of age. In 2005, the rate of suicide among adults older than 65 years was 14.3/100,000. Suicide accounts for 1.4% of all deaths in the United States. Although suicide is highest in white males older than 75 years (37.4/100,000), because there are many other reasons people of this age die, it is not among the leading causes of death for this group. Suicide rates are illustrated in Figure 1, which reflects data up to 2004, as the 2005 data are still preliminary. At all ages, the suicide rate is nearly four times higher in men than in women. The overall suicide rate in 2005 was 11.05/100,000, compared with the homicide rate of 5.9/100,000.

Figure 1. U.S. Suicide Rates of All Ages.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WISQARS.)

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR

Psychological autopsy studies (using systematic, detailed interviews and records about the deceased, with close relatives, friends, and caretakers of the persons who died by suicide) done in various countries over 50 years report remarkably similar outcomes. These studies show that more than 90% of people who die by suicide have one or more psychiatric disorders, most commonly major depression or bipolar depression, with alcohol or substance abuse reported as the second most common diagnoses (17–8). Individuals with other diseases, such as schizophrenia, anorexia, and some anxiety disorders, also have elevated rates of suicide compared with the appropriate age-matched populations (9). The personality disorders of antisocial and borderline are also prominent (10, 11). The surprising fact is that although there have been at least 117 psychological autopsy studies (12), post-traumatic stress disorder is seldom mentioned as an associated illness. This finding probably reflects the omission of the appropriate questions from the diagnostic interviews used in these studies. Although there is criticism about these studies, as they could not conceal the cause of death and in most cases there were no controls, the slightly variable but mostly consistent outcomes, as well as the fact that many of them were consecutive samples of those who died by suicide, probably give credence to the findings (13).

DEPRESSION AND DEATH BY SUICIDE

Looking at the issue in a different way, when patients with either major depression or bipolar illness are followed longitudinally for life, there is evidence that suicide is the leading cause of death for those with these disorders (14). The percentage who die by suicide depends on severity, with those who have been hospitalized for these disorders having higher suicide rates than those identified as outpatients. This fact was documented in a recent study by Angst et al. in 2002 (15), who showed that the suicide rates in patients with mood disorders followed for 40–44 years was 11.1%. The rates were highest among patients with major depression at 17.7%. In patients with bipolar disorder the rate was 11.4%. Prospectively, the suicide rate decreased over the 44-year follow-up. Treatment with lithium, neuroleptics (mainly clozapine), and antidepressants reduced the number of suicides significantly. Long-term treatment also reduced the overall mortality, and combined treatments proved more effective than monotherapy (16). Suicide is also a prominent cause of death for those with many other mental disorders, the exceptions being mental retardation or late-stage dementias.

RISK FACTORS AND SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR

COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS BETWEEN PATIENTS AND HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

There are ample data to confirm the fact that frequently people tell others they are contemplating suicide, but the percentage who communicate their intent to their doctors varies by age (58% of older people tell their primary care doctor in the month before the suicide and 77% in the prior year) (17). In a study of suicidal deaths in hospitals, 77% denied their intent on their last communication with the staff (18). Still, for every patient with depressive illness, there should be a record of depressive symptoms and suicidal intent on every visit to the doctor. This may best be accomplished by the use of a depressive symptom questionnaire such as the PHQ9 (Physician Health Inventory Self- Report) or some similar instrument. Certainly every medical student should be taught about the necessity of asking the questions related to suicidal intent in the appropriate patients (those with mental illness and with medical disorders who are depressed).

DIVERSE RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH DEATH BY SUICIDE

There are many risk factors associated with an outcome of suicide, although in any individual patient, it is impossible to predict. Individuals of all races, creeds, incomes, and educational levels die by suicide. There is no typical victim. In addition to the known psychiatric disorders, the other well-confirmed risk factor is a history of a past suicide attempt or a past serious plan and/or preparation for suicide (19). Unfortunately, there are many long-term follow-up studies of suicide attempters seen in an emergency setting, and they demonstrate that 7%–10% of these people eventually (up to 22 years later) die by suicide (20). It is true that if the patient is admitted to a hospital for at least 24 hours after an attempt, the likelihood of death by suicide increases substantially over that for those not admitted (21).

Other factors that are important when considering risk for suicide include a family history of suicide (22–25); the symptoms of hopelessness, anxiety, psychic anxiety, panic attacks, desperation, or being a burden in a person who is depressed (26, 27); a recent hospitalization for depression; drinking or drug use or abuse; and aggressive or impulsive personality traits (28). There are clear data showing that after a hospitalization for depression and a suicide attempt, careful aftercare, especially in the first week up to 1 month, reduces suicide rates. Other important factors to note are a history of trauma, abuse, or being bullied, chronic physical pain especially in elderly individuals, certain serious medical illnesses, and being a smoker (9, 29, 30). Environmental factors that must be part of the assessment are the access to lethal means (72% of elderly individuals kill themselves with guns) (31) and recent occurrence of other community or notable suicides that might create a “contagious” effect (32).

Treatment strategies and evidence

INTERVENTION AND AWARENESS OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR AND MENTAL ILLNESS

Despite the fact that we have many proven interventions (antidepressants and manual-based short-term psychotherapies), suicide rates are not falling. If we assume that therapies are efficacious, they may not be sought because there is still a stigma to admitting to mental illnesses or to seeking treatment. Another possibility is that illnesses associated with suicide are either not recognized by the affected people and their close relatives, friends, and physicians or the treatments being given are not optimal.

Interventions in the community include education and awareness for the general public and for general physicians. There are two successful programs, both from the armed service, here and in Norway showing that an intervention from the top down can decrease suicide or suicide attempts (33, 34). However, these programs have not been successfully transplanted to any civilian institution or group.

NEED FOR EXTENSIVE TRAINING FOR HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN TREATMENT AND PREVENTION STRATEGIES

There are now three studies from Europe, two from Sweden (35, 36) and one from Hungary (37), showing that educating general physicians to recognize depression and to treat the illness with antidepressants lowers the suicide rate in the population that is being served. In another study from Germany, with a similar program, the suicide rate did not decrease, although the recorded suicide attempt rate did (38). Although there is much emphasis on education for mental health professionals and gatekeepers such as school teachers, clergy, and policemen, the outcome of such programs in preventing suicide has not been proven. A recent study (39) with aggregate analysis showed that there is a strong state by state correlation between suicides and access to health care, which the authors interpret to mean that clinical intervention is the crucial element in the prevention of suicide.

Most of the data on education, interventions, and treatments come from studies involving patients who have made suicide attempts. As already stated, the relationship between changes in attempt rates with changes in suicide rates is tenuous.

The role of “simple” interventions

There are now several reports of simple interventions that either lower the suicide rate at follow up or lower the suicide attempt rate. The first was from the work of Motto and Bostrom (40). A group of 3,005 patients who had been hospitalized because of a depressive or suicidal state were contacted 30 days after discharge about follow-up treatment. They were asked if they had enrolled in and continued in the posthospital therapy plan for 30 days. Only 843 had not. These patients were randomly assigned to either a contact group or a no contact group. The contact group received a monthly letter for 4 months, then every 2 months for 8 months, and after the first year, a letter every 3 months for the next 4 years and were followed for up to 15 years. The letters were from the research staff member who had interviewed them in the hospital. They were short, expressing concern that the person was getting along all right, and invited a response. They were always worded differently, were individually typed, and included comments if the person had responded. In the 2,782 patients who could be followed for 5 years, the accumulated percentage of suicides was significantly lower for the first 2 years in those who got the letters compared with those who did not or those who at discharge claimed they were in follow-up treatment. Although the rates remained lower than those for the others for all 5 years, the difference was only significant in the first 2 years. Those who said they were getting treatment had the highest suicide rates at all points. Severity of illness at discharge was not assessed, but it may be that those who indicated they were engaged in the posthospital treatment plan had more severe illness. There is no information, however, about whether they actually were receiving treatment.

Carter et al. (41) reported on a somewhat different study from Australia where, after hospital admission for a suicide attempt by self-poisoning, 394 patients got treatment as usual and 378 got treatment as usual as well as eight postcards simply inquiring about their health over the following year. Although the percentage of repeaters was similar in the two groups, the number of suicide attempts greatly decreased in the group who received postcards compared with those who did not (101 compared to 192) because the repeats greatly decreased in those women with three or more attempts.

ACCURATE PRESCRIPTION OF ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Although percentages vary by study, probably only 20% of medicated depressed patients are adequately treated with antidepressants (42). There are a multitude of reasons proposed (43), which include failure/stoppage because of side effects, because the medications did not work, or because of cost, undermedication of patients, patients not taking the medication for fear of drug addiction, insufficient duration of treatment, patients not convinced that depression is an illness treatable by drugs, and undetected substance use or abuse. Additional problems arise because the physician does not combine the treatment with psychotherapy, does not use other medications, or does not consider all the options such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or other somatic therapies.

ACHIEVING REMISSION THROUGH LEVELS OF TREATMENT

The STAR*D study is an excellent example of several of the necessary options that should be pursued by patients and their doctors (44–48). It included 2,876 patients with depression (80% of whom had chronic or recurring depression) who were seen by a psychiatrist or a family care physician at multiple sites across the country. Patients could be included in the study if they had suicidal thoughts and/or a past suicide attempt. If they were found to have alcohol dependence, they needed to get substance abuse treatment before they entered the study. Everyone got the first medication, citalopram. The medication was given for at least 12 weeks and the dose was maximized. The outcome had to be remission, implying that the patient was almost well.

Only 33% of the patients achieved remission with the first medication. After that the patient was allowed to choose the next step(s) in treatment. The treatments varied by “steps” in the protocol but always allowed either an augmentation, which included psychotherapy or a switch in medication or to psychotherapy alone. There were four levels of treatments, each for 12 weeks unless the patient dropped out. By the end of the study 67% of the patients had achieved remission, although the relapse rate varied at each level. There were no differences between those treated by a psychiatrist or a primary care doctor. In all settings a depression rating scale was used to monitor treatment. The patients were called by staff to keep them involved in the protocol. The study was profound because it taught us if the first medication is pushed to its limits and the treatment is extended to 12–14 weeks, 33% of patients will achieve remission, half by 6 weeks and another half in the next 6–8 weeks. If the second step is taken and the patient stays in treatment, 50% of the patients achieve remission by 20 weeks. Although some may be disappointed by these results, it should be reassuring that with close care and monitoring half of outpatients will be in recovery. Returning to the data (35–37) showing that educating primary care physicians to recognize and treat depression with antidepressants lowers suicide rates, it is assumed that a treatment regimen in the STAR*D tradition could lower suicide rates.

It should be noted that Weissman (49), as part of the STAR*D collaboration, showed that if mothers are treated for their depressions and achieve remission, their children do better than those whose mothers did not achieve remission. In addition, from the STAR*D study, a genetic variation in the HTR2A gene and a new marker in the GR1K4 gene, which is a glutamate receptor, are reported to correlate with response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (50) and with a host of other findings. A recent STAR*D report in 2007 (51) indicated that there is a genetic marker for suicidal ideation. In this study, 1,915 outpatients with major depressive disorder were given optimal doses of the antidepressant citalopram. Within 12–14 weeks of treatment, 120 of these outpatients presented with treatment-emergent suicidal ideation. Two significant markers were found on the inotropic glutamate receptors, genes GRIA3 and GRIK2 in this sample, and the risk was more significant for those patients who carried both risk alleles. Two patients attempted suicide during this phase, and the one patient who participated in the gene collection, although he continuously denied suicidal ideation, carried the high-risk alleles for both genes.

QUESTIONS AND CONTROVERSIES

Numerous studies suggested an association between increased use of antidepressants and decreased rates of suicide, especially with “newer” antidepressants (13, 52–59). This finding would account for the falling rates of suicide in European countries through 2003. When the Food and Drug Administration became alarmed and called for a review of adverse events in the antidepressant drug trials, the blind rating of these events showed an increased risk of suicidal behavior in people up to age 24 after starting an antidepressant, but a protective effect against this behavior for older adults. This finding led to a black box warning for all antidepressants for those younger than age 25, a decrease in the diagnosis of depression in adolescents (60), and a decrease in the use of antidepressants. Some investigators maintained that the increase in suicide deaths resulted from this warning (61). The data from 2005 showed a decrease in suicide deaths, but it is unclear whether antidepressant prescriptions decreased, leveled off, or increased during this period.

Although it can be said, without question, that there is no relationship between death by suicide and starting an antidepressant, some evidence suggests that in adolescents there is an association between starting an antidepressant and an increase in suicidal thoughts and attempts, especially in the first 10 days of treatment. Because patients with suicidal ideas are frequently excluded from treatment studies, this suggestion is unexpected. The increase could be due to adverse events such as increased anxiety, agitation, restlessness, irritability, anger or akathisia, or an unrecognized switch into hypomania manifested by agitation and irritability (62). This means that physicians who treat adolescents need to develop strategies to warn them and their parents about this possible occurrence, to monitor them closely for the first 2 weeks, and to add agents to decrease anxiety and agitation if symptoms appear.

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE AUTHORS : THE MOST EFFECTIVE AND CONTEMPORARY MEDICATION AND THERAPEUTIC TECHNIQUES FOR SUICIDALITY

It is imperative that physicians who treat patients with mood disorders feel comfortable prescribing lithium. If they do not, then they should refer patients who do not respond to antidepressant and psychotherapy treatment to a physician who does use lithium. The evidence showing that patients who are taking lithium as well as other medications are significantly less likely in their lifetimes to die by suicide is overwhelming (63–68). For that reason it should be an option available to all patients with mood disorders. As already mentioned, in the long-term study of 406 patients with mood disorders who were followed for almost 40 years, (16) treatment with lithium, neuroleptics (primarily clozapine), and antidepressants significantly reduced suicide mortality and overall mortality (cardiovascular disease, strokes, and other causes).

In the same vein, one of the collaborative ECT studies also showed that for patients with suicide intent who received ECT, after three sessions 38% expressed no suicidal intent, after six sessions it was 61%, and after nine sessions 81% were without intent (69). An excellent review of the conclusions of these collaborative studies was recently published (70). Physicians who treat depressed patients should be amenable to offering patients this option.

In addition, research has shown that by treating suicidal outpatients with suicide attempt-directed cognitive behavioral therapy, suicide attempts are reduced by 50% over an 18-month period (71). There are other specific treatments that have also been shown to be effective in treating depressed or suicidal patients (including patients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorders) (72). Although each treatment is different, they are all short term (10–16 weeks) and structured (meaning that therapists should be able to give step-by-step treatment instructions that any other therapist can easily follow). Unfortunately, there are too few therapists trained to deliver these treatments (73). The other major effort to prevent suicide is the attempt of various countries to restrict means to suicide such as gun safety programs, bridge barriers, medication availability and packaging, and changes in domestic gas content and vehicle emissions (31, 74).

The review of these strategies gives hope for successful interventions, but it is clear that the effort must include training physicians to recognize and vigorously treat the psychiatric disorders that lead to suicide.

1 Robins E, Murphy GE, Wilkinson RH, Gassner S, Kayes J: Some clinical considerations in the prevention of suicide based on a study of 134 successful suicides. Am J Public Health 1959; 49: 888– 889Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Dorpat TL, Ripley HS: A study of suicide in the Seattle area. Compr Psychiatry 1960; 1: 349– 359Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Barraclough B, Bunch J, Nelson B, Saisbury P: A hundred cases of suicide; clinical aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 125: 355– 373Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Beskow J: Suicide and mental disorder in Swedish men. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1979; 277: 1– 138Google Scholar

5 Chynoweth R, Tonge JI, Armstrong J: Suicide in Brisbane—a retrospective psychosocial study. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1980; 14: 37– 45Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Rich CL, Ricketts JE, Young D, Fowler RC: Some differences between men and women who commit suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145: 718– 722Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Arató M, Demeter E, Rihmer Z, Somogyi E: Retrospective psychiatric assessment of 200 suicides in Budapest. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 77: 454– 456Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Kõlves K, Värnik A, Tooding L, Wasserman D: The role of alcohol in suicide: A case-control psychological autopsy study. Psychol Med 2006; 36: 923– 930Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Harris EC, Barraclough B: Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170: 205– 228Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Runeson BS, Rich CL: Diagnostic comorbidity of mental disorders among young suicides. Int Rev Psychiatry 1992; 4: 197– 203Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Rydelius PA: The development of antisocial behaviour and sudden violent death. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 77: 398– 403Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Pouliot L, De Leo D: Critical issues in psychological autopsy studies. Suicide Life Threat Behave 2006; 36: 491– 510Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Isacsson J: Depression is the core of suicidality—its treatment is the cure. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006; 114: 149– 150Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Guze SB, Robins E: Suicide and primary affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1970; 117: 437– 448Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Angst F, Stassen H, Clayton PJ, Angst, J: Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34–38 years. J Affect Disord 2002; 68: 167– 181Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Angst J, Angst F, Gerber-Werder R, Gamma A: Suicide in 406 mood-disorder patients with and without long-term medication: a 40 to 44 years' follow-up. Arch Suicide Res 2005; 9: 279– 300Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL: Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 909– 916Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Busch KA, Fawcett J, Jacobs DJ: Clinical correlates of inpatient suicide. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64: 14– 19Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Coryell W, Young EA: Clinical predictors of suicide in primary major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 4: 412– 417Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Jenkins JR, Hale R, Papanastassiou M, Crawford MJ, Tyrer P: Suicide rate 22 years after parasuicide: cohort study. BMJ 2002; 325: 115 5Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Beautrais A: Subsequent mortality in medically serious suicide attempts: A 5 year follow-up. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003; 37: 595– 599Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Wender PH, Kety SS, Rosenthal D, Schulsinger F, Ortmann J, Lunde I: Psychiatric disorders in the biological and adoptive families of adopted individuals with affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43: 1Google Scholar

23 Schulsinger F, Kety SS, Rosenthal D, Wender PH A family study of suicide, in Origin, Prevention, and Treatment of Affective Disorders. Edited by Schou M, Stromgren E. New York, Academic Press, 1979, pp 277– 287Google Scholar

24 Roy A, Segal NL, Centerwall BS, Robinette CD: Suicide in twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48: 29– 32Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Kim CD, Seguin M, Therrien N, Riopel G, Chawky N, Lesage AD, Tureki G: Familial aggregation of suicidal behavior: a family study of male suicide completers from the general population. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1017– 1019Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Beck A, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler, L: The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974; 42: 861– 865Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Fawcett J, Sheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R: Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147: 1189– 1194Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Mann J: Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Neuroscience 2003; 819– 828Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Angst J, Clayton P: Premorbid personality of depressive, bipolar, and schizophrenic patients with special reference to suicidal issues. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27: 511– 532Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Clayton PJ: Suicide and smoking (editorial). J Affect Disord 1998; 50: 1– 2Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Mann J, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H: Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005; 294: 2064– 2074Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Gould MS, Davidson L: Suicide contagion among adolescents, in Advances in Adolescent Mental Health: Depression and Suicide. Edited by Stiffman AR, Feldman RA. London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1988, pp 29– 59Google Scholar

33 Knox KL, Litts DA, Talcott GW, Feig JC, Caine ED: Risk of suicide and related adverse outcomes after exposure to a suicide prevention programme in the US Air Force: cohort study. BMJ 2003; 327: 1– 5Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Mehlum L, Scwebs R: Suicide prevention in the military: recent experiences in the Norwegian army, in Program and Abstracts of the 33rd International Congress on Miliatary Medicine, Helsinki, Finland, 2000Google Scholar

35 Rutz W, von Knorring L, Walinder J: Frequency of suicide on Gotland after systematic postgraduate education of general practitioners. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 80: 151– 154Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Henriksson S, Isacsson G: Increased antidepressant use and fewer suicides in Jämtland County, Sweden, after a primary care educational programme on the treatment of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006; 114: 159– 167Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Szanto K, Kalmar S, Rihmer Z, Hendin H, Mann JJ: A suicide prevention program in a very high suicide rate region. Arch Gen Psychiatry; 2007; 64: 914– 920.Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Hegerl U, Althaus D, Schmidtke A, Niklewski G: The alliance against depression: 2-year evaluation of a community-based intervention to reduce suicidality. Psychological Medicine 2006; 36: 1225– 1233Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Tondo L, Alpert MJ, Baldessarini R: Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: an ecological study. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67: 517– 523Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Motto JA, Bostrom AG: A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52: 828– 833Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Carter GL, Clover K, Whyte IM, Dawson AH, D'Este C: Postcards from the Edge project: randomized controlled trial of an intervention using postcards to reduce repetition of hospital treated deliberate self poisoning. BMJ 2005; 331: 80 5Google Scholar

42 Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walter EE, Wang PS: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289: 3095– 3105Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Haslam C, Atkinson S, Brown SS, Haslam RA: Anxiety and depression in the workplace: effects on the individual and organization (a focus group investigation). J Affect Disord 2005; 88: 209– 215Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenber AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M: Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical Practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 28– 40Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Steward JW, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Ritz L, Biggs M, Warden D, Luther JF, Shores-Wilson K, Niederehhe G, Fava M: Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1231– 1242Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Fava M, Rush AJ, Wisneiweski SR, Nierenberg AA, Alpert JE, McGrath PJ, Thase ME, Warden D, Biggs M, Luther JF, Niederehe G, Ritz L, Trivedi MH: A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1521– 1541Crossref, Google Scholar

47 McGrath PJ, Steward JW, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Davis L, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Luther JF, Niederehe G, Warden D, Rush AJ, for the Star*D trial team: Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medications trials for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1531– 1541Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, McGrath PJ, Alpert JE, Warden D, Luther JF, Niederhe G, Lebowitz B, Shores-Wison K, Rush AJ: A comparison of lithium and T3 augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1519– 1530Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Weissman MM, Pilowski DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King CA, Cerda G, Sood, AB, Alpert JE, Trivedi MH, Rush AJL: Remissions in maternal depression and child psychotherapy. JAMA 2006; 295: 1389– 1398Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Paddock S, Laje G, Charney DA, Rush J, Wilson AF, Sorant AJM, Lipsky R, Wisniewsk SR, Manji H, McMahon FJ: Association of GRIK4 with outcome of antidepressant treatment in the STAR*D cohort. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1181– 1188Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Laje G, Paddock S, Manji H, Rish AJ, Wilson AF, Charney D, McMahon FJ: Genetic markers of suicidal ideation emerging during citalopram treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1– 9Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL: Epidemiological data suggest antidepressants reduce suicide risk among depressives. J Affect Disord 1996; 41: 1– 8Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Rich CL, Isacsson G: Suicide and antidepressants in south Alabama: evidence for improved treatment of depression. J Affect Disord 1997; 45: 135– 142Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Ohberg A, Vuori E, Klaukka T, Lonnqvist: Antidepressants and suicide mortality. J Affect Disord 1998; 50: 225– 233Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Isacsson G, Holmgren P, Druid H, Bergman U: Psychotropics and suicide prevention: implications from toxicological screening of 5281 suicides in Sweden 1992–1994. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174: 259– 265Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Isacsson G: Suicide prevention-a medical breakthrough? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102: 113– 117Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik KL, Mann J: The relationship between antidepressant medication use and rate of suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 165– 171Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Korkeila J, Salminen JK, Hiekkanen H, Salokangas RKR: Use of antidepressants and suicide rate in Finland: an ecological study. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 505– 511Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Sondergard L, Kvist K, Lopez AG, Andersen PK, Kessing LV: Temporal changes in suicide rates for persons treated and not treated with antidepressants in Denmark during 1995–1999. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006; 114: 168– 176Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Erkens JA, Herings RMC, Mann JJ: Early evidence on the effects of regulators' suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1356– 1363Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, Orton HD, Allen R, Valuck RJ: Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 884– 891Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Baldessarini RJ, Pompili M, Tondo L: Suicidal risk in antidepressant drug trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63: 246– 248Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Cipriani A, Pretty H, Hawton K, Geddes JR: Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1805– 1819Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Kessing LV, Sondergard L, Kvist K, Anderson PK: Suicide risk in patients treated with lithium. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 52: 860– 866Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Felber W, Berghofer A, Lauterbach E, Ahrens, B: The impact of lithium long-term medication on suicidal behavior and mortality of bipolar patients. Arch Suicide Res 2005; 9: 307– 319Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P, Pompili M, Goodwin FK, Hennen J: Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long-term lithium treatment: a meta-analytic review. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8: 625– 639Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Gonzalez-Pinto A, Mosquera F, Alonso M, Lopez P, Ramirez F, Vieta E, Baldessarini RJ: Suicidal risk in bipolar I disorder patients and adherence to long-term lithium treatment. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8: 618– 624Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Guzzetta F, Tondo L, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ: Lithium treatment reduces suicide risk in recurrent major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 380– 383Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Kellner CH, Fink M, Knapp R, Petrides G, Husain M, Rummans T, Mueller M, Bernstein H, Rasmussen K, O'Connor K, Smith J, Rush AJ, Biggs M, McClintock S, Bailine MSS, Malur C: Relief of expressed suicidal intent by ECT: a consortium for research in ECT study. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 977– 982Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Fink M, Taylor MA: Electroconvulsive therapy. JAMA 2007; 298: 330– 332Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Brown GK, Have TT, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT: Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial, JAMA 2005; 294: 563– 570Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Guthrie E, Kapur N, Mackway-Jones K, Chew-Graham C, Moorey J, Mendel E, Marino-Francis F, Sanderson S, Turpin C, Boddy G, Tomenson B: Randomized controlled trial of brief psychological intervention after deliberate self-poisoning. BMJ 2001; 323: 1– 5Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SR, Betts K, Mufson L, Fitterling H, Wickramaratne P: National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63: 925– 934Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Bennewith O, Nowers M, Gunnell D: Effect of barriers on the Clifton suspension bridge, England, on local patterns of suicide: implication for prevention. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190: 266– 267Crossref, Google Scholar