Patient Management Exercise for Substance Abuse: Diagnosis and Treatment

Abstract

This exercise is designed to test your comprehension of material presented in this issue of FOCUS as well as your ability to evaluate, diagnose, and manage clinical problems. Answer the questions below, to the best of your ability, on the basis of the information provided, making your decisions as you would with a real-life patient.

Questions are presented at “decision points” that follow a section that gives information about the case. One or more choices may be correct for each question; make your choices on the basis of your clinical knowledge and the history provided. Read all of the options for each question before making any selections.

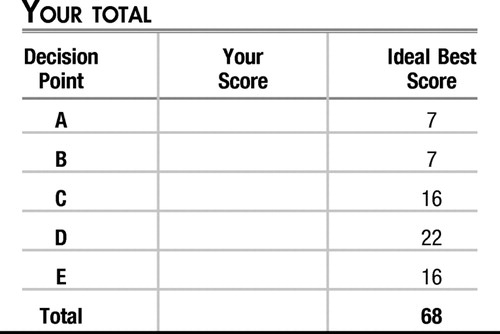

You are given points on a graded scale for the best possible answer(s), and points are deducted for answers that would result in a poor outcome or delay your arriving at the right answer. Answers that have little or no impact receive zero points. On questions that focus on differential diagnoses, bonus points are awarded if you select the most likely diagnosis as your first choice. At the end of the exercise you will add up your points to obtain a total score.

VIGNETTE PART I

You are an attending psychiatrist on an adult inpatient unit. You receive a call from the hospital's intensive care unit asking you to admit a 22-year-old man 4 days after the patient overdosed on an unknown quantity of psychoactive medications plus an unclear amount of acetaminophen. The college roommate who found him unconscious estimated that the patient probably ingested the pills between 5 and 8 hours before admission; the patient was intubated for 24 hours at the beginning of the hospitalization but was soon able to breathe on his own. His serum acetaminophen level was 225 μg/ml, his aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were 1,220/700 IU/L, and his urine toxicology screen was positive for opiates and cannabis. His blood alcohol level on admission to the emergency room was 0.28. His pupils were pin-point, suggesting opiate intoxication, and naloxone was administered. The medical team ordered that he be NPO and treated him with activated charcoal with gastric lavage and then began N-acetylcholine treatment over the next 72 hours and monitored him closely for the following 2 days. Normal saline, thiamine, and lorazepam, 1 mg i.v. every 2 hours, were administered during day 2 as the patient began to exhibit signs of acute alcohol withdrawal, including clouded consciousness, an inability to sustain attention, disorientation, and a core temperature of 39°C. He was treated for acute fulminant liver failure and responded quickly. According to the consultation-liaison (C/L) psychiatry resident who was called to see the patient on day 2, the patient continued to be delirious, irritable, agitated, and refused to speak, although he “kicked me out of the room.” He noticed, however, a pack of cigarettes in the patient's belongings bag.

According to the patient's mother, whom the C/L psychiatry resident was able to reach by telephone on the opposite coast, the patient made two prior suicide attempts, both by overdose of medications, and had two subsequent inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations. She suggested checking his thighs for cut marks as he had engaged in self-mutilation off and on since he was at least 12 years old. He spent 2 weeks at an outpatient alcohol and substance abuse rehabilitation program in California when he was 16 after he was caught smoking marijuana at home. He attended 90 Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, attending daily for 3 months (“90 in 90”) and then stopped going. He saw a psychotherapist sporadically from the age of 16 until he was 18 and was treated by a psychiatrist for major depression with fluoxetine 40 mg daily. He was accepted to a university in New York City.

When he was 6 years old he was sent by elementary school staff for a psychiatric evaluation because of inattentiveness and disruptive and impulsive behaviors. He was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Methylphenidate was prescribed. However his mother said she and his father refused to give it to him because they were afraid it would cause him to become addicted to the drug. He continued to struggle in school, but managed to earn good marks because of his “natural intelligence.” “He never had to study much,” his mother told the resident. According to his mother, she is not sure if he is still using street drugs or if he still takes his fluoxetine because he does not call home more than two or three times a year, “and only when he needs money.” She and her husband say their son does well in college and is due to graduate 1 year late after taking a year off to travel in Europe.

The lorazepam was slowly tapered beginning on hospital day 3 by 10%–15% per day. An antiemetic, non-opiate antidiarrhea formulation and fluids were administered or offered to help control the patient's withdrawal from opiates.

On hospital day 6 the medical team reports that the patient's vital signs have normalized, his acetaminophen level is 0, and his liver enzyme levels are moving toward normal limits, so you accept the transfer. The patient arrives several hours later, somewhat lethargic after he was given haloperidol 2 mg i.m. and lorazepam 1 mg i.m. by the treatment team after he learned he would be transferred to the psychiatry inpatient unit, had pulled out his intravenous lines, and leave the hospital against medical advice. Six hours later, the patient is still lethargic, but his heart rate is 110 and blood pressure is 160/100 mm Hg. To control the patient's withdrawal symptoms, he was initially titrated to lorazepam 2mg every 4 hours. Prior to arrival on the inpatient psychiatric unit, the patient's lorazepam regimen had been tapered to 1.5mg every 4 hours, for a total of 9mg/day. The patient's vital signs normalize for approximately 4 hours, but he again becomes tachycardic and hypertensive.

DECISION POINT A

Given what you know about this patient's history of alcohol abuse and current symptoms, his refusal to speak with the resident, and not yet having spoken with him yourself, what would be the safest next step?

| A1.___ | Until you are able to accurately assess the quantity and frequency of his alcohol abuse, you should not administer any additional pharmacotherapies. Wait until he is sober and able to provide a more detailed history to guide your decision making. |

| A2.___ | Until you are able to accurately assess the quantity and frequency of his alcohol abuse, you should not administer any additional pharmacotherapies. However, you should order aspiration precautions, ask nursing staff to provide visual cues to orient patient to time and place, and continue to monitor his vital signs every 2 hours for the first 12 hours and then every 8 hours. Apply a nicotine patch, 14 mg, and every 24 hours adjust according to symptomatology or to the patient's self-reported amount of smoking. |

| A3.___ | Continue the lorazepam taper by 10% every day. Tell the patient you noticed his cigarettes and offer him a nicotine patch to help withdrawal from cigarette smoking because smoking is not permitted in the hospital. |

| A4.___ | Order aspiration precautions because of the high dose of lorazepam, ask nursing staff to provide visual cues to orient the patient to time and place, and continue to monitor his vital signs every 2 hours for the first 12 hours and then every 8 hours. Start lorazepam 2 mg p.o. every 4 hours, holding the dose for sedation. Continue the taper by 10%–15% daily. Ask the patient if he would like a nicotine replacement therapy as he may be feeling agitated as a result of not smoking, which he cannot do in the hospital. |

| A5.___ | The patient is now out of the window for delirium tremens and his withdrawal symptoms are improving. Schedule him for outpatient follow-up within 3 days of discharge and give him chlordiazepoxide 50 mg tablets, 1 tablet every day for 3 days. |

DECISION POINT B

Given what you know, how should you approach this patient?

| B1.___ | Have the patient sign release of information forms to enable you to speak with his parents, psychiatrist, and therapist in California. Call each and obtain as much collateral information as you can. |

| B2.___ | Have the patient sign release of information forms to enable you to speak with his parents, psychiatrist and therapist in California. However, wait until the patient is more cooperative so you can explain what information you are seeking from these other sources. |

| B3.___ | Ask the patient to sit up and, if necessary, to splash water on his face so you can speak with him about the suicide attempt that led to this hospitalization. |

| B4.___ | If the patient refuses to speak with you, tell him he will not be going anywhere until he does. Explain that his suicide attempt was very serious, and you cannot allow him to leave the hospital in this condition. |

| B5.___ | Have the patient sign release of information forms to enable you to speak with his parents, psychiatrist, and therapist in California. Call each and obtain as much collateral information as you can. Ask the parents to fly to New York to participate in their son's treatment as he is abusing substances and the most effective strategy requires family work. |

VIGNETTE PART II

You obtain consent from the patient to speak with his parents, his psychiatrist, and therapist in California. The patient is still refusing to speak with you about the suicide attempt. He asks repeatedly for “something to mellow me out” because “I'm really stressed and I'm going to explode.” You explain that he is being carefully monitored for withdrawal symptoms, discomfort, and his lorazepam is being tapered. He becomes irate and screams, “Get out of my room! Get me a doctor who knows what he's doing. You are trying to torture me because that is what you get paid to do.” Using a calm voice you explain again that the staff is carefully monitoring him, but you are unable to finish your sentence because he throws a shoe at you, which fortunately misses and hits the wall instead.

You contact the patient's mother who explains that she and the patient's father divorced 6 years ago after she caught him cheating with his legal secretary. She has one other child, a daughter, 20 years old, who attends a private college in northern California. The daughter briefly saw a therapist during the divorce. She was also diagnosed with ADHD when she was between 6 and 7 years of age; like her brother, she was never given the methylphenidate she was prescribed. She is not doing well in school, has a history of running away from home, using drugs, and underwent an elective abortion at the age of 15 after a rape.

The patient's mother suffers from depression and takes escitalopram. Her depression was diagnosed 1 year before the divorce. The patient's father allegedly has alcohol dependency that is untreated, but has not yet interfered with his ability to function as a malpractice attorney. She is not certain whether her parents had any psychiatric problems, but her father-in-law died of pancreatic cancer related to heavy drinking. She warns you not to call her ex-husband because he remarried, and has two young children and does not want to be involved.

The patient's former psychiatrist and therapist inform you that the patient's two previous suicide attempts, at ages 16 and 17, were probably related to his parents' divorce when he turned 16. They recall that the patient was diagnosed with ADHD by history that was not treated, but say he was lucky that he maintained good enough grades to move on to a university in New York. He had at least five episodes of major depression, beginning when he was 10 years old when he claimed that his father sexually molested him. The family was investigated by Child Protective Services, and no charges were made.

He again exhibited symptoms of depression at 12 and 15 years of age, the longest lasting 4 months, but his depression became disabling when he was 16, lasting more than 6 months and leading to his first suicide attempt. In between bouts of depression he says he felt “normal.” During his depressions, however, he had anhedonia, was isolative, and ignored his friends. He typically lost 10% of his already lean body mass, had difficulty with sleep, and poor energy. After he was 16, he felt the divorce was his fault and continually ruminated with intrusive negative thoughts about himself. He never exhibited psychotic symptoms, homicidal ideation, or paranoid delusions. His mood was never elevated or euphoric, although he says it can change rapidly from “normal” to “really depressed.” The mood switching can happen several times in a day and last a day or up to several months. There is no history of aggression toward people or animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness or theft, or serious violations of rules. He abused alcohol by binge drinking on weekends with friends beginning at the age 15. By the time his parents divorced, he was drinking by himself during the week as well.

His psychiatrist diagnosed him with “strong cluster B symptoms,” but explains that he feels the patient's personality structure has taken on borderline personality disorder characteristics. By the time the patient was 12 it was noticed that he had begun cutting his thighs with a razor. The cuts were superficial, but there were numerous scars from his self-mutilation efforts and during visits typically six to eight fresh marks. None ever required sutures.

His friendships were of a fleeting nature. He would come to therapy or to see the psychiatrist extolling the virtues of his closest friends, but by the next month or two these friends had become enemies. Romantically, the patient seemed ambivalent about whether he preferred women or men and seemed to struggle with his own sexual identity. He often slept with strangers he met at bars, although he reported that he always used a condom. Even when he was in a better mood, he still complained of feeling empty, that his life was ruined, and he repeatedly blamed himself for his parents' divorce. He felt they may have set him up, to be the scapegoat for their decision to divorce by continually punishing him for alleged misconduct and poor grades, despite his “being the best son anyone could possibly want.”

Therapy was started with fluoxetine 20 mg, which was increased to 60 mg over the next 4 months. He stopped taking the medication and seeing his therapist because he said he “felt fine” but again became depressed and made the second suicide attempt approximately 4 months later. He returned to the psychiatrist and therapist after a week-long hospitalization, and fluoxetine was restarted but was quickly titrated back to 60 mg. Again, once he felt better he quit coming to appointments and stopped the medication. He called the therapist one last time before leaving for New York.

His mother reported that he was excited to start at the university, felt good about his academic achievements, and seemed to have put the events surrounding his parents' divorce into better perspective. He acknowledged that their divorce had nothing to do with him or his sister; his father had cheated on his mother, and although he still harbored resentment toward his father, he told the therapist that he wanted to concentrate on his studies. She gave him referrals for a psychiatrist and therapist in New York City, but apparently he never followed up on them.

DECISION POINT C

Match the following drugs/substances with their approximate detection duration by urine toxicology screening:

On hospital day 8 the patient has calmed down considerably and decides to speak with you. You ask him what precipitated the overdose. “I could not take it anymore,” he tells you. “I have been lying to everyone to the point where I do not know which way is up. I am tired. I cannot handle all of the pressure anymore. I do not know what I'm going to do.” His eyes become glassy and he grabs a few tissues. He tells you he is “pissed off” that his suicide attempt failed. When he sleeps he wakes up every hour or so and feels overwhelmed by his problems. He says he feels hopeless, helpless, and worthless. He cannot focus on anything, not even TV, and he has not been eating well. He apologizes for his behavior then blames the nursing staff for not helping him with PRN [as needed] medications. “You should fire half this staff,” he tells you. “I've seen them do things to other patients that would get them arrested.” You ask about his alcohol consumption. He tells you that he has been drinking on and off since the age of 12. “I can put away a fifth if I want.” He began drinking by stealing sips of his father's drinks. He liked the way it felt and began stealing bottles from what he describes as “a huge bar.” By the time he was 13 he was drinking 5 shots of vodka per night before bedtime. He would binge drink on the weekend and often blacked out, and “I ended up in some pretty odd places doing some very odd things.” He does not want to tell you about those incidents. He managed to maintain sobriety for 6 months when he started college, but this situation quickly deteriorated and he was again binge drinking. “My parents do not know this, but I was kicked out of school after my sophomore year.” You ask what he has been doing for money and he replies that his parents send him large checks periodically “because I figure they owe me” and he also does “things” for money he prefers not to discuss.

You tell him you found evidence of opiates and marijuana in his urine toxicology screen. He admits to smoking marijuana infrequently, perhaps once per 1–2 months, only if someone “shoves a joint in my mouth.” He does not use opiates, but overdosed on “a couple of handfuls of Vicodin” that his roommate had hidden because he sold the pills. “I do not get into that either,” he says. “But I needed pills and they were around.”

Regarding his general health, he reports that he is healthy, has had recent tests for sexually transmitted diseases including HIV infection, all of which were negative. In the past he contracted a chlamydial infection that was treated successfully with antibiotics. He says “the one thing I do right is practice safe sex.” He says he smokes one pack of cigarettes per day and has smoked since he was 15 years old.

DECISION POINT DGiven what you know about this patient, what is your differential diagnosis? (+2) points for correct responses, including appropriate rule-out diagnoses, and (−2) points for incorrect responses.

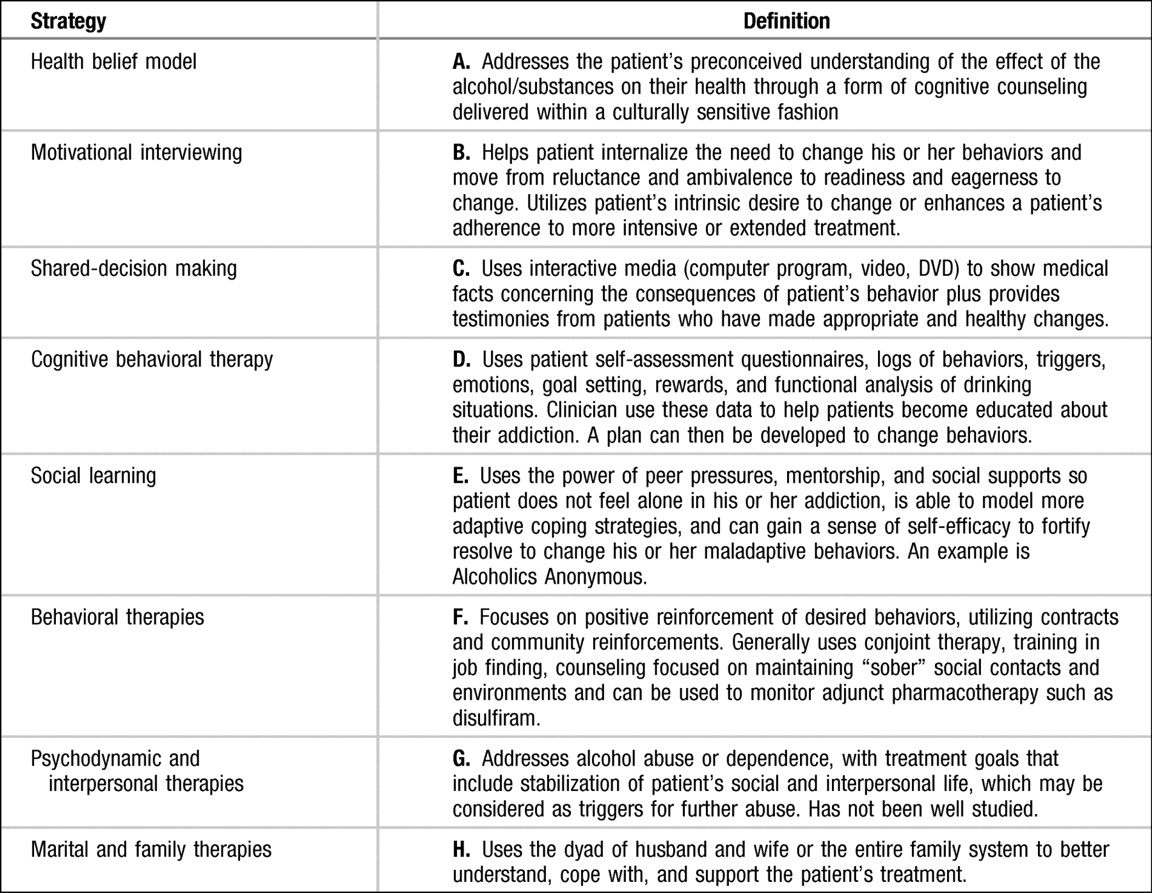

According to a meta-analysis of studies measuring the effectiveness of education and counseling to help patients make behavioral changes, no single intervention appeared more effective than others in changing behaviors, whether the purpose was to 1) add a behavior, 2) eliminate nonaddicting behavior, or 3) eliminate addicting behavior. However, four strategies demonstrated the greatest change in promoting better health habits:

| 1. | Rewarding the patient for positive behavior | ||||

| 2. | Using multiple forms of information | ||||

| 3. | Self-pacing and tailoring the intervention to the patient's needs | ||||

| 4. | Providing feedback information about the change in health status measures. | ||||

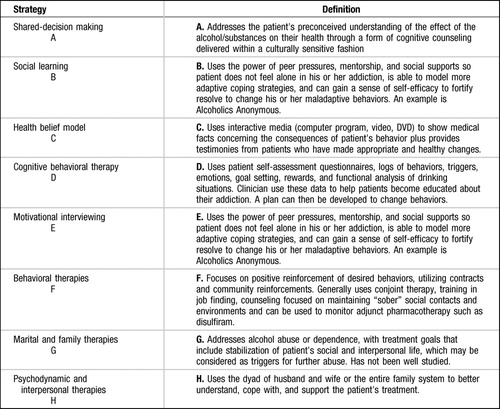

Match the following variety of specific strategies for patient education and counseling with their corresponding definitions:

High positive scores (+3 and above) indicate a decision that would be effective, would be required for diagnosis, and without which management would be negligent. Lower positive scores (+2) indicate a decision that is important but not immediately necessary. The lowest positive score (+1) indicates a decision that is potentially useful for diagnosis and treatment. A neutral score (0) indicates a decision that is neither helpful nor harmful under the given circumstances. High negative scores (−5 to −3) indicate a decision that is inappropriate and potentially harmful or possibly life-threatening. Loser negative scores (−2 and above) indicate a decision that is nonproductive and potentially harmful.

DECISION POINT AThe goal of treating this patient's acute alcohol and opiate intoxication as well as treating the overdose on acetaminophen were managed by the medical intensive care unit before the patient's transfer to the inpatient psychiatric unit. His withdrawal symptoms should decline sharply within the first 4–12 hours after his last drink and will peak in intensity by the 2nd day. He should begin to feel somewhat better by day 4 or 5. Symptoms include agitation, hyperactivity, anxiety, hand tremors, nausea or vomiting, insomnia, hallucinations or illusions with clear sensorium, tonic-clonic seizures, increased startle response, increased tendon reflexes, and orthostatic hypotension. Delirium tremens, a medical emergency, typically begins 48–96 hours, possibly up to 1 week after cessation of alcohol intake. This occurs in less than 5% of individuals and is heralded by the onset of delirium in most cases.

Like alcohol, opiates are short-acting; withdrawal from these substances is not likely to cause death. Patients typically experience withdrawal symptoms beginning from 6 to 24 hours after last dose, peaking at 48–72 hours, and lasting 7–10 days. This patient, owing to the context of overdose, was treated initially with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, to reverse the opioid effects. For treatment of mild to moderate withdrawal from opiates or maintenance therapy for withdrawal from opiates, patients typically can be treated with opioid agonists such as methadone, agonist/antagonists such as buprenorphine, or non-opioid agonists such as clonidine, an α2-agonist antihypertensive drug that helps reduce insomnia, restlessness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle aches, and craving. Both buprenorphine and methadone are both metabolized by the liver, buprenorphine by one P450 enzyme and methadone by several P450 enzymes. Given the orthostatic hypotension caused by alcohol withdrawal, the emergency team chose to avoid clonidine. Studies have shown that buprenorphine is better tolerated and has greater acceptance for the treatment of mild to moderate opiate withdrawal by addicts. If the patient has ingested a high dose of opiates, buprenorphine can worsen the symptoms of withdrawal because of its antagonist properties. There are no well-designed studies at this time comparing buprenorphine with methadone, although methadone has also been shown to be very effective in acute withdrawal. Both buprenorphine and methadone are used for long-term stabilization and help with eventual cessation.

Nicotine withdrawal typically presents as a dysphoric or depressed mood, insomnia, irritability, frustration, or anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, decreased heart rate, and increased appetite or weight gain. The symptoms and craving begin within 24 hours and decline gradually over a period of 10 days to several weeks. The patient is 6 days from his last cigarette and may be irritable and uncomfortable in part because of nicotine withdrawal. Offering him one of the nicotine preparations, such as Nicorette gum, the nicotine inhaler, or a nicotine patch would help alleviate these symptoms and help toward convincing the patient to quit smoking.

He is now 6 days free of alcohol and opiates and medically stabilized. His starting dose of lorazepam was 12 mg/day. He arrives on your unit with his lorazepam dose at 9 mg/day.

| A1.___ | −5 This answer is incorrect because the patient requires some pharmacotherapy to manage his acute withdrawal from alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. |

| A2.___ | −2 This answer is incorrect regarding pharmacotherapy for the reasons explained in A1; however, adding environmental cues and aspiration precautions is helpful for a patient who has been delirious from hepatotoxicity, alcohol, and a drug overdose. The patient does not require such vigilant checking of his vital signs: every 8 hours is sufficient. Applying a nicotine patch is a good idea but should first be discussed with the patient and his permission should be obtained. |

| A3.___ | +2 Continuing the lorazepam taper by 10% per day and offering a nicotine patch are appropriate choices to help the patient's withdrawal from both alcohol and nicotine. However, the best answer should include aspiration precautions and monitoring vital signs for safety, and environmental cues to help the patient orient to time and place. |

| A4.___ | +5 This is the best answer. |

| A5.___ | −5 The patient should not be discharged for clear reasons of safety. He made a serious suicide attempt that has not yet been addressed, and he clearly is dependent upon alcohol. More history is required, and appropriate psychiatric follow-up must be arranged. |

| B1.___ | +5 The only way to truly assess this patient, especially given his dependence upon alcohol and abuse of substances, is to gather collateral information. |

| B2.___ | −5 It is not necessary to wait to gather collateral information. You should not rely on the hope that the patient will become cooperative in a timely manner. |

| B3.___ | −5 This patient is recovering from his overdose and experience in the intensive care unit. You do need to learn about the suicide attempt, but an aggressive approach will probably ruin any chance of establishing a good rapport so he can comfortably speak about sensitive issues. |

| B4.___ | −5 Although it is true that the patient will probably remain an inpatient as long as he is unstable and uncooperative, and if you cannot establish a safe disposition, you should avoid the overly aggressive approach for the same reasons described in answer B3. |

| B5.___ | +2 Gathering collateral information will help you understand your patient better. Having the patient's parents join in the treatment process could lead to a better outcome. However, this depends entirely upon their current relationship and ability to fly from California to New York. Additionally, the two parents are not on speaking terms so this fact may further alienate one or both from the process. |

Score +2 points for each correct answer.

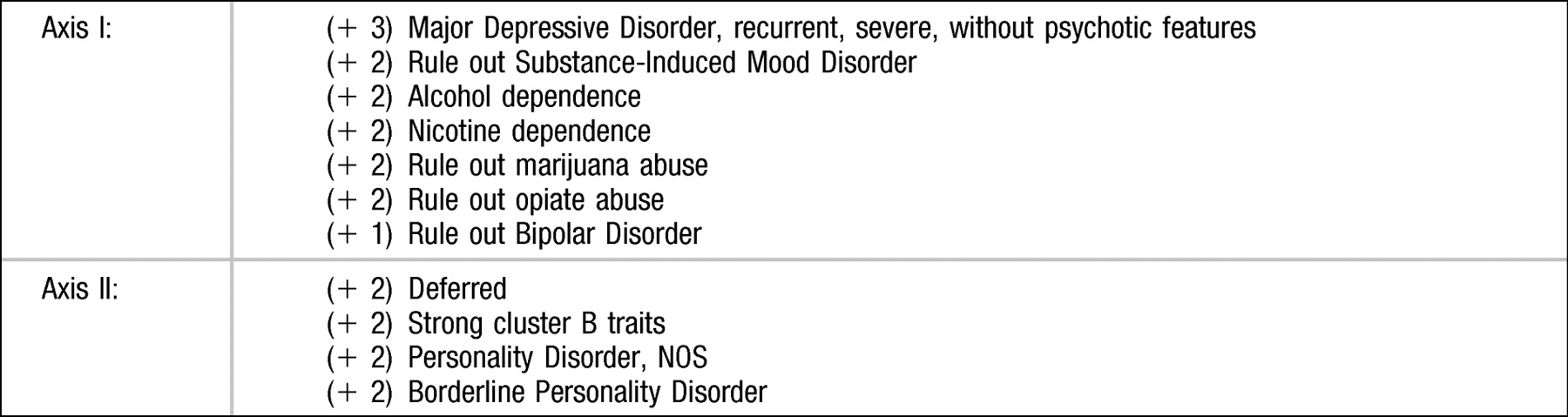

The patient arrives in your inpatient unit after a serious suicide attempt using an overdose in the context of heavy alcohol use. Subsequently, your initial evaluation may be complicated by whether this is a primary substance abuse or a dependence problem with subsequent mood symptoms or whether there is an underlying mood problem that is complicated by the dual diagnosis of a substance abuse or dependence diagnosis. Once you start to gather collateral information, and the patient begins to share more of his history, you learn that he has suffered at least five episodes of major depression beginning at 10 years of age, the longest lasting 6 months and ending with his first suicide attempt. He has been hospitalized twice previously for suicide attempts, has a history of self-mutilating behavior, and was diagnosed with ADHD as a child.

His current symptoms include disturbed sleep, feeling hopeless, helpless, and worthless, an inability to focus, and poor appetite. Because his mood symptoms preceded his abuse of alcohol and later substances by at least 2 years, it is likely that his mood symptoms underlie his substance and alcohol issues. Given that his major depressive episodes have lasted more than 2 weeks at a time, but less than 2 years, with symptom-free periods lasting greater than 2 months in between episodes, he can be diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, recurrent (+2 points). The severity of the symptoms, including suicide attempts, justifies the qualifier “severe,” and he has not experienced any psychotic symptoms. Because the longest episode lasted 6 months, he does not qualify for Dysthymic Disorder (−2 points). However, given that this mood disorder did take place in the context of alcohol and substance abuse or dependence, one could write a rule-out for Substance-Induced Mood Disorder (+2 points).

Both he and his collateral informants have not endorsed any symptoms of mania or hypomania. However, when considering the early age at onset of depressive symptoms, the recurrence throughout adolescence, and the unclear family history (the father and paternal grandfather's alcohol dependence are strongly comorbid with mood disorders), it is not unreasonable to keep bipolar disorder as a rule-out. However, it would probably be lower on the differential (+1 point).

Given the earlier diagnosis of ADHD, this diagnosis could at least be carried over, listed as a rule-out, or listed in the patient's psychiatric history.

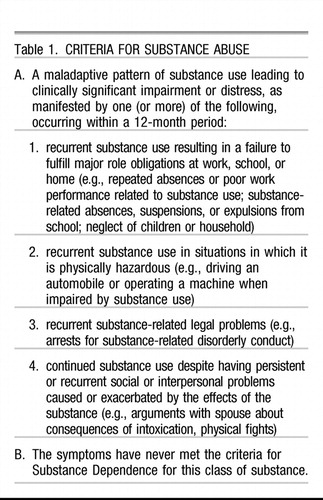

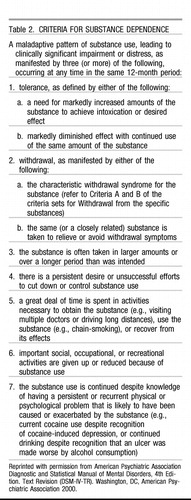

The differences between substance abuse and dependence as described by DSM-IV-TR are related primarily to the extent of disability caused by the use of this substance and the inability of an individual to cease using the substance:

|

Table 1. CRITERIA FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE

|

Table 2. CRITERIA FOR SUBSTANCE DEPENDENCE

This patient clearly has an alcohol dependency (+2 points) and a nicotine dependency (+2 points), but the evidence for making a diagnosis of cannabis abuse is not clear at this time other than the patient's admission he used it (but not frequently) and it showed up in his urine toxicology screen. Subsequently, a rule-out for cannabis abuse is warranted (+2 points). The patient used Vicodin (oxycodone-acetaminophen) tablets to overdose. He denies using opiates and claims he chose this drug because it was what he had available to him. Until we obtain a more detailed history of his opiate use we can write ‘rule out opiate abuse’ (+2 points).

On axis II, the patient's admission that he has difficulty with interpersonal relationships, using black-and-white-type thinking, in which he is either “extolling the virtues” of his friends, or they are enemies. He describes mood lability, but no elevated or euphoric moods. He is easily irritable and demonstrates that while in the hospital. Finally, he has long demonstrated poor impulse control, using drugs, suicide attempts, self-injurious behaviors, ambivalence about his sexual identity, and relative sexual promiscuity. These personality traits have been enduring, and over the years have caused him to have interpersonal conflicts; in addition, the possibility that he was sexually molested as a young boy by his father led to an investigation by Child Protective Services. Subsequently, the patient meets criteria for Personality Disorder, not otherwise specified (+2 points).

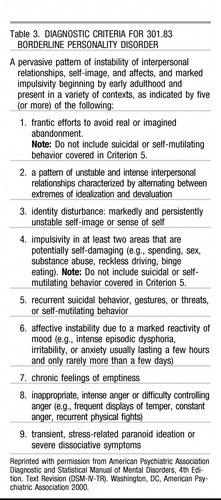

Table 3 lists the DSM-IV-TR criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder.

|

Table 3. DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR 301.83 BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

This patient presents with a history that is very suggestive of Borderline Personality Disorder, and, given his age, it is possible to diagnose this disorder. However, diagnosing personality disorders is very difficult if the clinician does not know the patient well, in the context of a severe mood disorder or episode, and in the context of substance abuse or dependence. If the underlying mood disorder is treated and the substance abuse or dependency issues are treated, and the patient still demonstrates a maladaptive personality structure, the diagnosis is much clearer. For this patient, given the long history taken from the patient and his mother, it is safe to label him as a rule-out Personality Disorder, not otherwise specified (+2 points), rule-out Borderline Personality Disorder (+2 points), or write “strong cluster B traits” (+2 points). The latter is not an official DSM-IV-TR diagnosis, but could help other clinicians who may treat this patient in the future. Writing “Deferred” is also appropriate if the clinician prefers to either wait to get to know the patient better and under sober and mood symptom-free circumstances (+2 points).

DECISION POINT EScore +2 points for each correct answer.

Azrin NH: Improvements in the community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther 1976; 14: 339– 348Crossref, Google Scholar

Bandura A: Social Foundation of Thoughts and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1986Google Scholar

Chaney EF: Social skills training, in Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches. Edited by Hester RK, Miller WR, New York, Pergamon Press, 1989, pp 206– 221Google Scholar

DeBellis R, Smith BS, Choi S, Malloy M: Management of delirium tremens. J Intensive Care Med 2005; 20: 164– 173Crossref, Google Scholar

DiMatteo MR. The Psychology of Health, Illness and Medical Care: An Individual Perspective. Pacific Grove, CA, Brooks/Cole, 1991Google Scholar

Dunn C, Deroo L Rivara FP: The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction 2001; 96: 1725– 1742Crossref, Google Scholar

Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O'Connor PG: Outpatient management of patients with alcohol problems. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133: 815– 827Crossref, Google Scholar

Femino J, Lewis DC: Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome: Monograph 272. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1982Google Scholar

Gallant D: Alcohol, in The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment, 2nd ed. Edited by Galanter M, Kleber H. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1999, pp 151– 164Google Scholar

Gordon GH, Duffy FD: Educating and enlisting patients. J Clin Outcomes Med 1998; 5: 45Google Scholar

Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, Fenwick JW: A behavioral approach to achieving initial cocaine abstinence. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148: 1218– 1224Crossref, Google Scholar

Hodgson R: Treatment of alcohol problems. Addiction 1994; 89: 1529– 1534Crossref, Google Scholar

Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D: Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal. CMAJ 1999; 160: 649– 655Google Scholar

Holder HD, Longabaugh R, Miller WR, Rubonis AV: The cost effectiveness of treatment for alcoholism: a first approximation. J Stud Alcohol 1991; 52: 517– 540Crossref, Google Scholar

Hunt GM, Azrin NH: A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther 1973; 11: 91– 104Crossref, Google Scholar

Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, Wang MC: Efficacy of relapse prevention: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67– 563- 570Crossref, Google Scholar

Mayo-Smith MF: Pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal: a meta-analysis and evidence-based practice guideline. American Society of Addiction Medicine working Group on Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal. JAMA 1997; 278: 144– 151Crossref, Google Scholar

McClellan T, Dembo R: Screening and Assessment of Alcohol- and Other Drug-Abusing Adolescents: Treatment Improvement Protocol Series 3. Rockville, Md, U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1993, p 116Google Scholar

Meichenbaum, D, Turk, DC: Facilitating Treatment Adherence: A Practitioner's Guidebook. New York, Plenum Press, 1987Google Scholar

Miller WR, Munoz RF: How to Control Your Drinking, revised ed. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1982Google Scholar

Miller WR, Hester RK: Inpatient alcoholism treatment: who benefits? Am Psychol 1986; 41: 794– 805Crossref, Google Scholar

Miller, WR, Rollnick, S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

Miller WR, Wilbourne PL: Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction 2002; 97: 265– 277Crossref, Google Scholar

Monti PM, Abrams DB, BinkoffJA, Zwick WR, Liepman MR, Nirenberg TD, Rohsenow DJ: communication skills training, communication skills training with family and cognitive behavioral mood management training for alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol 1990; 51: 263– 270Crossref, Google Scholar

Price JL, Cordell B: Cultural diversity and patient teaching. J Contin Educ Nurs 1994; 25: 163– 166Crossref, Google Scholar

Russell, ML: Behavioral Counseling in Medicine: Strategies for Modifying At-risk Behavior. New York, Oxford University Press, 1986Google Scholar

Sanchez-Craig M: Therapist's Manual for Secondary Prevention of Alcohol Problems: Procedures for Teaching Moderate Drinking and Abstinence. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Addiction Research Foundation, 1984Google Scholar

Schwazzer R: Self efficacy, physical symptoms and rehabilitation of chronic disease, in Self-Efficacy: Thought Control in Action. Edited by Schwazzer R. Washington, DC, Hemisphere Publishing, 1992Google Scholar

Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, Krystal JH: Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res World 1998; 22: 61– 66Google Scholar