Individual, Group, and Multifamily Cognitive-Behavioral Treatments

Since the early 1980s, the psychosocial treatment of choice for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has been exposure for obsessions and prevention of rituals, or “response prevention,” for compulsions conducted mainly in an individual format. This treatment method, based on clinical observations that obsessions increase anxiety and compulsions reduce it, has now been incorporated into the diagnostic criteria for OCD. That is, obsessions “cause marked anxiety or distress” and compulsions “are aimed at preventing or reducing distress” provoked by obsessions (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Not surprisingly, behavioral treatment based on this model includes procedures to reduce anxiety associated with obsessions and to prevent or curtail ritualistic behavior. In this chapter we briefly describe the theoretical model for exposure and response prevention (ERP) and then review the empirical literature supporting the efficacy of this method. In addition, cognitive conceptualizations and interventions have gained considerable recent attention and the limited literature on this method will also be reviewed. Promising alternative treatment strategies to deliver ERP, group, and multifamily formats offer added advantages that may be particularly beneficial to some patients, so we present literature relevant to group and multifamily behavioral treatment as well.

Behavioral models

Foa and Tillmanns (1980) articulated a definition of OCD based on the functional relationship between obsessions and compulsions—that is, the thoughts, images, impulses, or actions that generate obsessive anxiety may be prompted by external (environmental) or internal (thoughts, images) triggers for fear. Obsessive fears may be accompanied by fears of potential disaster (e.g., disease, death, going to hell), or they may occur without fears of catastrophic consequences. Most sufferers try to avoid the feared situation or stimuli (passive, phobic-like avoidance), but when this is difficult or impossible, they usually perform overt rituals or covert mental events to restore safety or prevent harm (Rachman 1976). Both behavioral and mental rituals are functionally equivalent in that both are intended to reduce obsessive fear (Rachman 1976; Rachman and Hodgson 1980).

Why obsessions become highly anxiety provoking in the first place is the subject of some debate that remains unresolved. Possible etiologic models include parental teachings and modeling, biologic sources, cultural factors, historical experiences, religious teachings, cognitive beliefs and appraisals, and many other variables. ERP treatment, however, is based on the assumption that thoughts and behaviors are learned responses that have become conditioned and generalized to various contexts despite their seeming irrationality.

Behavioral theorists (e.g., Dollard and Miller 1950; Mowrer 1960) have proposed a two-stage theory of acquisition of fear in which individuals first associate fear or other emotional discomfort with particular situations for various reasons and then find that escaping from or avoiding those contexts reduces discomfort. Because most patients cannot easily avoid many fear-provoking situations (e.g., use of toilets or stoves, perverse religious ideas), they develop ritualistic behaviors such as washing, checking, or praying to prevent or reduce discomfort, even if only minimally or briefly. Such actions are reinforced and repeated precisely because they reduce discomfort. Supporting this hypothesis is substantial evidence from early studies of OCD that obsessions increase both subjective and physiologic anxiety or discomfort and that compulsions reduce it (e.g., Boulougouris et al. 1977; Hodgson and Rachman 1972; Hornsveld et al. 1979; Rabavilas and Boulougouris 1974; Roper et al. 1973). The treatments that logically derive from this learning theory model are exposure to foster habituation of obsessive fears and blocking of rituals to prevent escape and avoidance.

Assessment of symptoms

Before beginning behavioral (or cognitive) treatment, it is important for the clinician to gain a full picture of the OCD symptoms and their function for the patient. A complete assessment of symptoms consists of interview data (from the patient and, if possible, from family members or close others), clinician assessment of symptom types and severity, and standardized self-report measures.

In an initial evaluation interview, preparatory to conducting a behavioral treatment, clinicians should assess obsessions and compulsions separately, along with mood state and general functioning. Rating scales include the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al. 1989a, 1989b), used either as a rater-administered measure (Woody et al. 1995) or as a self-report (Steketee et al. 1996). Other necessary self-report instruments include a comprehensive list of feared and avoided situations as well as internal thought images and impulses.

Outstanding among standardized clinician ratings of severity is the Y-BOCS, favored because of its detailed assessment of the severity of idiographic symptoms without regard to particular types of obsessions or compulsions. This measure begins with the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist to determine which obsessions and compulsions occur most frequently for a particular patient and to identify other, less frequent or disturbing OCD symptoms that may prove problematic during behavioral treatment. After administering the Symptom Checklist, the clinician uses the Y-BOCS scale to assess five aspects each of obsessions and compulsions: time spent, distress, interference, resistance, and control. Scores range from 0 to 40. Scores of 16 and above are considered to be in the clinically significant range, with scores above 28 in the severe to extreme range. Positive evidence for the reliability and validity of the Y-BOCS is available in recent studies (e.g., Woody et al. 1995). A self-report version of this measure has demonstrated good reliability and validity in studies of clinical and nonclinical samples (Steketee et al. 1996). However, for patients with very poor insight into the irrationality of their symptoms, the clinician-rated Y-BOCS may be more valid.

Observational measures of the frequency and duration of ritualistic behavior are recommended because these bring the clinician closest to an understanding of the impact and role of obsessions and compulsions in the patient’s everyday life. Self-reported minutes spent on compulsive activity have been collected in some studies to provide an independent assessment of symptom severity before and after therapy (Emmelkamp and van Kraanen 1977; Foa et al. 1980b), although the reliability and validity of such measures have not been established.

Behavioral treatment

Variants of exposure and blocking procedures have been used very successfully for patients with OCD who have covert and overt rituals. Direct exposure techniques require the patient to directly confront fearful or disturbing ideas or situations and may be accompanied by exposure in imagery to feared catastrophic outcomes. Response prevention or blocking methods halt the patient’s ritualistic behaviors. To block “mental compulsions,” strategies such as thought stopping or distraction can be useful. These treatment strategies follow from the conceptualization of OCD described earlier; procedures that reduce anxiety (e.g., exposure) are applied specifically to anxiety-provoking obsessional content, whereas blocking strategies (e.g., response prevention) are used to prevent cognitive and behavioral rituals, thus allowing for habituation of obsessive fears. Both interventions are necessary for patients with obsessions accompanied by compulsions, as discussed later (Steketee 1993b; Steketee and White 1990).

The combining of exposure for obsessions with response prevention for compulsions was first employed by Meyer in 1966 in patients with washing and cleaning rituals. In this program, compulsions were prevented while the patient was required to repeatedly touch objects that evoked anxiety about “contamination” and consequent urges to wash (Meyer and Levy 1973; Meyer et al. 1974). Studies using variants of direct exposure techniques were compared with relaxation training, both in conjunction with response prevention. Of the patients treated with ERP, 75% were improved or much improved after 15 sessions and maintained their gains after 2 years; by contrast, relaxation training had no effect (Marks et al. 1975). In two studies from Greece, an average of 11 sessions of in vivo and imaginal exposure plus response prevention produced good results in 85% of patients (Boulougouris and Bassiakos 1973; Rabavilas et al. 1976), but a long-term follow-up indicated that only 60% were still improved (Boulougouris 1977). Several studies by investigators in the Netherlands used 10–15 sessions of in vivo exposure and blocking of compulsions. Overall, about 70%–80% of a large sample of patients with OCD improved and most remained so at follow-up, although some patients required additional treatment sessions (Boersma et al. 1976; Emmelkamp and van Kraanen 1977; Emmelkamp et al. 1980; Hoogduin and Duivenvoorden 1988).

In the initial studies by Foa and Goldstein (1978) in the United States, after 10 sessions of daily imagined and in vivo exposure treatment, 85% of patients were nearly symptom-free on rituals and only one patient failed to show improvement on obsessions, but fewer (57%) were asymptomatic. At follow-up, approximately 15% of patients relapsed. These findings indicated that treatment was somewhat more effective with compulsions than with obsessions, results that have held up in subsequent studies of exposure therapy. Later studies showed very positive gains with 15 sessions of treatment (Foa et al. 1992); most treatment regimens generally provide between 12 and 15 sessions of ERP.

Although “pure obsessionals” (OCD patients without overt rituals) have traditionally been considered more difficult to treat with ERP, studies suggest that careful application of this behavioral treatment may result in substantial improvement for some patients. For instance, Hoogduin et al. (1987) treated 26 obsessive patients with a systematic program of deliberate evoking of obsessional thoughts (exposure) combined with strategies for refraining from neutralizing thoughts and cognitive rituals (response prevention). Nineteen subjects (73%) showed improvement of greater than 30%, and 61% of these maintained their gains at a 1-year follow-up. Salkovskis and Westbrook (1989) outlined some helpful approaches to invoking an ERP treatment paradigm with pure obsessionals, including the use of tape-recorded obsessional thoughts to allow for deliberate exposure.

To date, prolonged ERP has been used to treat hundreds of patients with OCD, with most data derived from group studies. The remarkable convergence of results from studies conducted in many centers attests to the generalizability of the treatment effects. It is not surprising that, at present, ERP is considered the psychologic treatment of choice for OCD.

Although the basic components of ERP have been well established, further work has been done to explore the relative importance of the various components, specifically, the relative need for exposure as well as response prevention, the required duration of the exposure, and the need for a therapist to model the behavior. Meyer’s original treatment consisted of two basic components: exposure to discomfort-evoking stimuli and prevention of ritualistic responses. Theoretically, exposure should be necessary to reduce anxiety associated with obsessions, and ritualistic behavior should be blocked because it terminates confrontation with the fearful stimuli, thus preventing extinction of anxiety. The research data support these assumptions. However, both in case studies and in controlled comparisons, obsessive anxiety declined more after prolonged exposure rather than after blocking of rituals, and compulsions were reduced mainly by response prevention but not by exposure (Foa et al. 1980a, 1984; Mills et al. 1973; Turner et al. 1980). Thus, not surprisingly, combined treatment led to the best results. From a clinical standpoint, therapists should gradually expose patients to situations that provoke obsessions while at the same time preventing the rituals that usually occur in these circumstances.

According to clinical studies of patients with OCD, prolonged exposure to fear-provoking stimuli is superior to brief exposure: 80 minutes of continuous direct in vivo exposure proved superior to eight 10-minute segments (Rabavilas et al. 1976). Surprisingly, however, duration of the imagined exposure did not affect outcome. How quickly the therapist moves up the hierarchy of disturbing stimuli has not proved to be important in the treatment of OCD. Hodgson et al. (1972) exposed some patients gradually and others immediately to the most feared situation. The two procedures were equally effective, although patients reported feeling more comfortable with the gradual approach. We suspect from clinical experience that progressing too slowly will be unhelpful for most patients whose motivation and sense of accomplishment may wane. In general, then, clinicians are advised to extend patients’ exposure experiences in the office and at home as long as feasible and to encourage them to confront their fears as rapidly as they can tolerate.

A combination of response prevention and participant modeling, in which the patient copied the therapist’s demonstration of exposure, yielded better results than passive modeling in which the patient only observed the therapist (Roper et al. 1975). However, other investigators found that adding modeling did not improve outcome (Boersma et al. 1976; Rachman et al. 1973). Nonetheless, some patients have reported that observing the therapist helped them overcome their resistance and avoidance of exposure. How the therapist models or conducts exposure may influence patients’ willingness to continue in treatment. Marks et al. (1975) proposed that ERP treatment requires a good therapeutic relationship and often a sense of humor. The very limited research on the qualities of a good therapist for OCD indicated that therapists who were respectful, understanding, interested, encouraging, challenging, and explicit were able to help patients achieve greater gains than those who gratified dependency needs or were permissive or tolerant (Rabavilas et al. 1979). In practice, a combination of support, encouragement, humor, and firm insistence that the patient follow therapeutic instructions for ERP seems to be optimal.

Although the personal style of the therapist may be important, his or her presence during exposure may not be required, at least in some cases. Emmelkamp and van Kraanen (1977) found no differences in outcome for self-controlled versus therapist-controlled exposure, although subjects in the therapist-led group required more treatment sessions at follow-up than did the other group. The authors suggested that the self-controlled exposure patients may have gained greater independence in handling their fears. Consistent with this earlier study, the addition of therapist-aided exposure after 8 weeks of self-exposure instructions yielded only transient benefits that were lost at week 23 (Marks et al. 1988). Preliminary trials of computer-aided exposure suggest that such treatment may prove very useful for selected individuals with OCD (Greist 1996; Griest et al. 1996). The findings of these studies do not suggest that therapists are dispensable but do indicate that direct exposure may be implemented without their immediate presence. Whether this is especially true for patients with mild to moderate (rather than severe) symptoms remains to be tested.

In conclusion, it seems that both exposure and blocking of mental and overt rituals are needed for successful outcome. Imagined treatment may be especially useful when fears of disasters are prominent features of a patient’s OCD symptoms. From a clinical standpoint, research suggests that therapists may begin treatment by conducting prolonged exposure in office and then assigning more exposure as homework between sessions. Only if the patient has serious difficulty with homework should the therapist insist on being present through the process. Most patients are likely to prefer graduated exposure, but some circumstances may require more rapid confrontation. Modeling may be used whenever patients feel it would be useful.

Cognitive models

It is apparent from the phenomenology and characteristics of OCD that patients with this disorder exhibit some disturbances in cognitive functioning. Accordingly, several cognitive models for OCD have been proposed, many of which emphasize similar features of the disorder (see Steketee et al. 1998 and summary below). Pitman’s (1987) cybernetic model suggested that faulty beliefs and pathologic symptoms of OCD stem from signals experienced internally, such that a perceptual mismatch is registered in the perception of the input. This faulty perception leads to pervasive uncertainty and ritualistic efforts to correct it, along with difficulty withdrawing attention from intrusive thoughts. Pitman proposed neuroanatomic underpinnings for these processes.

From a more traditional cognitive perspective, Warren and Zgourides (1991) emphasized the role of irrational beliefs in a rational-emotive treatment (RET) model of OCD. They hypothesized that biologic vulnerability influenced by developmental and learning experiences determined which thoughts a person considers unacceptable and what meaning he or she attaches to the thoughts. Common irrational thoughts include assumptions about the need to make correct decisions, the need to be perfectly certain to avoid causing harm, and the unacceptableness of bizarre thoughts and impulses. According to the RET model, under stress, negative emotions tend to provoke such intrusive thoughts. Thereafter, attention narrows on these thoughts, with accompanying hypervigilance and efforts to avoid or escape them (see also Wegner 1989).

Salkovskis (1985) and Rachman (1993) formulated cognitive models focused on the salience of common intrusive thoughts associated with negative automatic thoughts. Discomfort arises from mistaken assumptions about responsibility for endangering oneself or others, leading to self-blame and precautions to avoid guilt, shame, and depression. Neutralization (mental and behavioral rituals) serves to reduce discomfort, responsibility, and the possible consequences of having the thought. Freeston et al. (1996) broadened this formulation to include additional types of faulty appraisals, including overestimation of the consequences of thoughts and of anxiety, the presumption that thinking can lead directly to doing an act (thought–action fusion), and perfectionism and the need for control.

Additional hypothesized cognitive distortions include overestimation of threat or harm (Carr 1974; McFall and Wollersheim 1979), problems with epistemologic reasoning associated with safety (Kozak et al. 1987), a need for certainty (Beech and Liddell 1974), ideas that one must be perfectly competent and that failure to do so should be punished (Guidano and Liotti 1983; McFall and Wollersheim 1979), feelings of loss of control of thoughts (Clark and Purdon 1993) and consequent efforts at suppression (Wegner 1989), and underestimates of coping capacity (Carr 1974; Foa and Kozak 1986; Guidano and Liotti 1983). Experimental findings have supported some of the above assertions, particularly with respect to overspecification, the need for certainty (Makhlouf-Norris and Norris 1972; Makhlouf-Norris et al. 1970; Milner et al. 1971; Persons and Foa 1984; Reed 1985; Volans 1976), and excessive responsibility (e.g., Lopatka and Rachman 1995; Rheaume et al. 1995; Salkovskis 1989). Evidence is now accumulating to substantiate several aspects of these theoretical ideas, but it will undoubtedly be some time before the relationship among these concepts and their importance for effective treatment is clearly articulated.

Cognitive treatment

To date, only a handful of studies, most of them uncontrolled, have attempted to determine whether treatments derived from cognitive models are fruitful for OCD. In an earlier study, cognitive methods proved minimally helpful in reducing OCD symptoms (Emmelkamp et al. 1980). In contrast to these disappointing findings, a study of RET compared with self-controlled ERP showed that both treatments improved OCD symptoms equally (Emmelkamp and Beens 1991; Emmelkamp et al. 1988).

However, the above-mentioned cognitive therapies did not appear to be designed specifically for cognitive distortions typical of patients with OCD. If certain cognitions (e.g., excessive responsibility, overestimation of harm, need for control) are particularly germane to OCD, cognitive treatment focused on these patient-specific thoughts and beliefs may be even more effective (Beck and Emery 1985). Several case studies demonstrated good effects of a traditional Beckian cognitive therapy tailored specifically for participating OCD patients (e.g., Ladouceur et al. 1993; Salkovskis and Warwick 1986; Van Noppen et al. 1995). Treatment included socratic dialogue and the triple column technique, which consisted of listing thoughts/beliefs, and rating the strength of conviction in the belief, associated emotions, and possible alternative beliefs. Experimental testing of beliefs and other cognitive strategies were intended to dispute various OCD-associated distorted beliefs. This cognitive treatment was highly successful, reducing Y-BOCS scores by 11 points after treatment and 12 points at 6-month follow-up. This outcome matched the effects of ERP (Van Noppen et al. 1995). These findings suggest that cognitive therapy is a promising adjunctive or, perhaps, alternative treatment to ERP.

Many clinicians providing behavioral treatment informally incorporate cognitive techniques into the therapy. Psychoeducation and the labeling of OCD symptoms are standard in our treatment and likely to alter cognitive misinterpretations. We also encourage patients to separate affect (“I feel as though I have to wash”) from distorted perceptions, assumptions, and beliefs (“I have to wash or I’ll get AIDS”) and to challenge faulty assumptions about harm, perceived responsibility, and unacceptableness of bizarre thoughts and impulses. A group context (see below) is particularly suitable for providing a normative consensus to test beliefs and rehearse alternative ways of thinking. The case example below illustrates ERP with an individual patient.

Case example

Rick, a 40-year-old computer systems support analyst, sought individual behavioral treatment after 10 months of pharmacologic treatment with limited benefits. He was married, the father of an 18-month-old son, and of Italian-Catholic descent. Although he was raised in a devout family, he described himself as not religious and “liberal” in his political views.

Upon initial evaluation, Rick spoke about “disturbing” thoughts that interfered with his ability to enjoy his wife, Susan, and their son, Nate. Completion of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist revealed primary aggressive obsessions, a need to know, considerable avoidance, reassurance seeking, and mental rituals. Rick described “worrying that I might have the ability to impulsively hurt my son or wife....Suppose I just do it for no reason at all.” He was very bothered by the constant distraction of these “horrible” thoughts, which arose when he was in the company of his wife and son. Rick dreaded the days he had to drive Nate home from day care and be with him alone at home; when his wife was home he felt reassured that his “impulses” might stay in check. Although Rick had no previous history of difficulty with loss of impulse control or aggressive outbursts, he was worried that “what if, one day, I might just lose control and do something awful?” When questioned about insight, Rick wavered, acknowledging that his fears and behaviors were unreasonable but uncertain whether he had reason to be concerned. Rick’s initial Y-BOCS score was 25, reflecting moderate severity of symptoms, 3–8 hours a day of obsessions and compulsions, and little sense of control over the OCD.

Rick described mild childhood obsessive-compulsive symptoms that included an excessive need for reassurance, a fear of “germs,” and some body dysmorphic symptoms (e.g., a preoccupation with his appearance, concern that he was “ugly,” checking in mirrors). In his late teens and early 20s, Rick’s fear of germs became more predominant, and on his own he used confrontation to help his fear “fade away.” He sought psychiatric treatment at age 19 because he was having difficulty with social relationships at college and was feeling insecure and inadequate. Aggressive obsessions began to emerge. In his psychodynamic approach, he examined his relationships in his family of origin and intrapsychic conflicts. After 10 years of weekly psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, Rick felt more “normal” socially and was able to have some meaningful relationships, graduate from college, secure a job, and live on his own. When he first presented for treatment, he knew he had OCD but spoke about the aggressive thoughts as though they were reflective of suppressed anger.

An individual behavioral treatment was outlined for Rick, who agreed to a protocol of two 90-minute information-gathering sessions, 12 weekly 2-hour treatment sessions, and six monthly check-in sessions. He decided to be maintained on a stable dose of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) throughout the therapy. During the first two information-gathering sessions, a more detailed history was taken; the intrapersonal behavior therapy was described, including a definition of ERP; and a more detailed description of Rick’s OCD was elicited. Rick seemed motivated, engaged, and eager to get started. The therapist instructed him to read When Once Is Not Enough (Steketee and White 1990) during the first few weeks. He came to the first session with his exposure homework hierarchy folded into a tiny square. Rick stated that he was so ashamed of his thoughts and fearful that “if anyone knew” just what he thought, they might think he was capable of doing these terrible things and “put him away.” He said he had never disclosed the exact content of his thoughts before and felt anxious to do so. Worried that someone would find the paper, he had put it in an envelope, placed the envelope into a jar, and hid the jar inside a bag of fertilizer, which he had then put into the trunk of his car and covered with a blanket. Thus, the very process of articulating the internal cues/triggers required Rick to expose himself to the obsessive thoughts and feared catastrophic consequences—in this case, that if he told someone about his obsessions, he would require hospitalization and possibly face divorce and loss of custody.

Rick’s therapy was based on his exposure hierarchy, which was constructed around his fears of harming his wife and son. Table 1 lists obsessive thoughts and situations and the subjective discomfort they provoked on a scale of 0–100. Similarly, a hierarchy of situations that Rick avoided or endured with anxiety was constructed; this is shown in Table 2.

Treatment, which consisted of ERP in vivo, imagined exposure in vivo, homework ERP assignments, and self-monitoring, proceeded based on these hierarchies. The first few sessions also contained psychoeducation on OCD, reading assignments (finish reading When Once Is Not Enough), and the viewing of a videotaped discussion by Michele T. Pato, M.D., on the neurobiology of OCD.

Because of the nature of Rick’s aggressive obsessions, most of the in vivo therapy involved the use of scripted imagery that he read aloud, audiotaped, and replayed. He was given instructions to write the scripts in the first person and to be as descriptive and detailed as possible, as though the obsessive idea or image were happening. Whenever possible, the therapist encouraged Rick to bring “props” to the sessions to heighten his discomfort. For example, to confront the fear of smashing his son in the head with a hammer, Rick brought in a hammer and pictures of his son. The exposure task was for Rick to look at the pictures while swinging the hammer toward the photos and saying “I will smash Nate in the head with a hammer.” Initially, Rick said “I’m afraid I will hit my son in the head,” but the therapist reminded him of the scripting instructions, adding that to make the technique effective he needed to confront the exact fear. As the behavioral treatment continued, Rick combined in vivo and imaginal exposure using a bat, scissors, and knives (first small then large). Rick found the in vivo practice, coupled with the exposure homework, to be highly effective in reducing his anxiety. The day Rick entered the session with a baseball bat hidden under his coat, he laughed and joked with the therapist about becoming a “bat killer.”

The therapist used modeling, often participating in the exposure challenge when Rick expressed difficulty getting started. For instance, the therapist took out a picture of her daughter, jabbed a knife at the photo, and said “I will stab Jill!” Observing this, Rick asked with puzzlement, “Doesn’t that bother you? You seem so calm about saying that...almost with no emotion.” The therapist asked Rick how other people would feel about the same thought. He said that they “wouldn’t think it in the first place.” The therapist provided information that many people have intrusive aggressive thoughts but dismiss them as such. She pushed him to reflect further on this—to think about the process of OCD rather than the content. In other words, it was not the thought itself that created the problem, it was the worrying about the thought or the thinking about the thought that was the real problem in OCD. Such mainly cognitive interventions are intended to redefine the feared ideas or images as normative intrusions about which the patient has become oversensitive.

Rick was diligent about following through on his homework assignments, and within 4 weeks he reported only very mild distress evoked by purposeful or spontaneous exposure to the thoughts that had been in the 40–50 range initially. ERP proceeded in a step-wise fashion. Rick self-monitored his anxiety levels and stayed in exposure situations until his distress declined significantly. He listened to his scripted imagery tapes in the car on the way to pick his son up from day care, when he was alone with his son, and while unloading knives from the dishwasher; thus, he became able to practice independently outside of the sessions.

Rick reported that the indifferent response he received after disclosing the detailed content of his thoughts was a therapeutic breakthrough for him because he had never “divulged his worries” to anyone before. To be able to discuss the content in such a matter-of-fact way reinforced the idea that the thoughts were in fact meaningless. This in-session experience, coupled with the between-session ERP practice, reduced the intensity and frequency of Rick’s obsessive-compulsive symptoms so that by session 8, he was able to confront his “worst” fear of strangling Nate. After the second reading, followed by several repetitions of listening to the tape, Rick reported a decline in distress (50). Rick was gradually able to view the strangling fear as “just another OCD thought” without becoming embroiled in analyzing the content. Rick’s assignment was to go home and practice putting his hands around Nate’s neck while allowing the “terrible” thoughts to come to his mind without engaging in mental rituals or reassurance seeking to decrease his anxiety. Again, the therapist reminded him he would most likely feel very anxious at the start but to stay with the anxiety, rating it every 10 minutes on his self-monitoring form until it diminished considerably.

At session 9, Rick reporting feeling proud of himself that he listened to the tape and performed the exposure exercise repeatedly to the point of no longer feeling the previous dread and fear. He rated his discomfort at 40, less than half of the initial rating. After the 12 weekly sessions, Rick’s symptoms had dramatically reduced in frequency and intensity and his functioning had improved. His posttreatment Y-BOCS score was 8, indicating mild obsessive-compulsive symptoms that intruded less than 1 hour per day with control over obsessions and compulsions.

Key elements in this case were the positive therapeutic relationship that developed between Rick and his therapist, the therapist’s empathic yet firm stance, consistent use of in vivo and imaginal exposure, response prevention, reviewing of homework, and Rick’s motivation to overcome the OCD despite previous failure in therapy.

Group behavioral treatment

Group behavioral treatments have proven effective for several other patient populations with anxiety disorders, but only a handful of studies, most of them uncontrolled, have investigated group treatments for OCD (Epsie and Michelson 1996; Hand and Tichatzky 1979; Taylor and Sholomskas 1993). This treatment holds considerable interest because of its potential for reducing costs without sacrificing benefits. Furthermore, the group context may offer added benefits for patients with OCD who experience stigma and social isolation or who need the motivational boost of a supportive treatment group. Yalom (1975) identified “curative factors” at work in group therapy, such as cohesiveness, imitative learning, imparting of information, and universality, that are clearly present in behavioral treatment groups for patients with OCD. Also, Budman (1981) recognized the importance of time-limited models of group therapy for pragmatic, economic reasons and to enhance motivation.

Four large uncontrolled trials have been reported. Enright (1991) used nine weekly 90-minute sessions with the addition of assertiveness training. Significant decreases in OCD symptoms and depressed and anxious mood and improvement in functioning were evident at posttest and at 6-month follow-up, although only 17% of those studied made clinically significant improvement according to strict standards. It is noteworthy that this study included less focus on exposure and blocking of rituals during sessions. In a second trial, Krone et al. (1991) treated 36 patients with OCD using short, 7-week group programs of education, instruction in cognitive and behavioral self-treatment, and therapist-directed ERP. Significant improvement was evident in the reductions of Y-BOCS scores from moderately severe before therapy to below clinical levels at 3-month follow-up. Interestingly, this improvement was independent of medication use. In another study, 10 sessions of group ERP produced moderate reductions (5–6 points) in the Y-BOCS scores of 90 outpatients with OCD, which were noted at least 6 months after treatment (Van Noppen et al. 1998).

Finally, Fals-Stewart et al. (1993) have conducted the only controlled trial for OCD comparing group imagined and/or in vivo ERP (N=30) with comparable individual ERP (N=31) and an individual relaxation control treatment (N=32). After 24 twice-weekly sessions, subjects in both ERP treatment conditions showed significant improvement in OCD symptoms, depression, and anxiety at posttest and follow-up, whereas the control group changed only on anxiety. Group treatment led to substantial reductions of 10 points in Y-BOCS scores at posttest and 8 points at follow-up, results quite similar to those of Van Noppen et al. (1998). Unfortunately, this study excluded patients with major depression and Axis II diagnoses, limiting the generalizability of these findings.

However, it is apparent from the above case series and controlled trial that behavioral treatment can be applied to group contexts with results that are generally equivalent to those of individual treatment, particularly when the number of sessions is comparable with that usually provided to individual patients in other controlled research (12–20 sessions). For clinical settings in which there is sufficient patient flow but a limited number of trained therapists, this is clearly a cost-effective and efficacious alternative to standard individual treatment.

Case example: group behavioral treatment

Eight patients with OCD were referred for group behavioral treatment. They were initially screened by an experienced clinician and then evaluated by the group therapist to ensure appropriateness for group treatment. Each patient participated in two 90-minute information-gathering sessions before starting with the group. During these meetings, the therapist collected general information; history of OCD, other symptoms and mental health treatment; and a general history about family and social relationships. The detailed information about OCD symptoms was used to generate a hierarchy that each patient brought to the first group session. The goals of the group therapy were outlined, OCD and behavior therapy were defined, and family members were invited to accompany the patient to the first half of the second information-gathering session, although they were not involved in the treatment. The behavioral treatment group ran for 12 consecutive weeks with each session lasting 2 hours.

The first three sessions consisted of introductions and psychoeducation about phenomenology, etiology, and behavioral and cognitive techniques. Simultaneously, in-group ERP was demonstrated and practiced and group modeling took place. Patients were required to select homework assignments and record daily distress levels between group sessions. After completing the active treatment of 12 sessions, the group members continued to meet for six monthly sessions to consolidate their treatment gains and discuss relapse prevention. Some of the details of these group sessions are highlighted below.

GBT Session 1. The therapist discussed confidentiality, coverage between groups, a crisis plan, and the importance of consistent attendance and posed questions such as “What do you hope to get out of this group?” and “What do you expect to gain from this group?” A handout entitled “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: What is OCD?” was distributed, and each patient took turns reading aloud from it. Each patient was given the self-rated version of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist to review, with members volunteering to read. Allowing patients to draw from their experience of OCD in order to provide examples for each symptom type promoted disclosure. Jan, a single, 34-year-old computer programmer, spoke about her extensive repeating rituals to ward off “bad things from happening.” Relieved to hear this, Dan, a married, 52-year-old salesman, told the group about his fear of the number 4 and how he “couldn’t say that number” in the same sentence as one of his kid’s names because they might get hurt and it would be his fault. “Oh, everything’s always my fault!” chuckled Jan. The group laughed along with her at this common trait, underscoring a general theme of excessive responsibility. Others felt inspired by these stories, and it generated discussion about the effect of OCD on people’s lives. The group’s “curative factors,” as described by Yalom (1975), were evident even in this first session. The group process appeared effective in decreasing feelings of isolation, stigma, and shame while universalizing problems, instilling feelings of hope, and using imitative behavioral methods to promote change.

Disclosure during the group session paved the way for the use of ERP and modeling. In addition, the heterogeneity of symptoms seemed to promote insight by facilitating greater participation in the in vivo exercises that led to group normative behavior and beliefs. For example, it would be difficult to get a group of eight patients with contamination fears to agree that people should be able to touch the flusher of a toilet and resist washing their hands without feeling significantly anxious. Patients had learned to appreciate the various forms of symptoms that allowed them to depersonalize the obsessive content.

After disclosing their situation, patients were asked to select an item in the 35–45 discomfort range from their personal hierarchy as part of their ERP homework. Homework forms were distributed (as they would be in every subsequent session) and explained. The therapist instructed the group members to record their distress levels throughout the week while practicing their homework task. Everyone was reminded of the time-limited nature of the group and that there was a lot to cover in a relatively short period of time.

GBT Session 2. At the second session, patients reported on their homework, receiving praise for accomplishments and problem-solving feedback when they experienced difficulties achieving habituation. The group input was intended to expand behavioral alternatives and offer consensual validation on normative beliefs and behaviors. Mark said it was helpful to talk with other patients with OCD and to “hear that no one else gets upset when they hear what I do. When I’m here, I feel at home because everybody has their weird worries and strange behaviors. We can laugh at ourselves without feeling like freaks that no one else can relate to. We know we aren’t alone!” During this psychoeducational phase, the therapist also introduced the concept that although patients “feel” or “think” they have to perform their rituals, almost everyone spoke in absolutes: “I have to check,” “I have to straighten the magazines.” She attempted to get them to restructure this cognitive distortion by having them restructure their speech from “I have to check” to “because of my OCD I think (or feel) I have to check.”

After the therapist gave a detailed 15-minute overview of in vivo and imaginal exposure, examples of these techniques were practiced in the group. Chuck and others in the group were asked to take out their wallets, shuffle around the money and credit cards, report on their distress, put the wallet away, continue to monitor the distress, then repeat the task. All of the patients rehearsed their exposure tasks and rated their discomfort levels. The exercises were repeated until discomfort was reduced. This in vivo exposure was very lively, as is typical in group behavioral therapy.

During this time, some patients displayed tremendous discomfort and seemed to benefit from the support, feedback, and encouragement of the other patients to stay in the dreaded situation. Most patients reported that it was invaluable to observe others exposing themselves to stimuli and experiencing mounting anxiety and, after repeated and prolonged exposure, watching their discomfort recede. Thus, although therapist modeling has not been shown empirically to improve outcome, patients have reported that participant modeling was beneficial to them. For homework, the patients often continued their in-group challenges and added items from their hierarchies. The exposure homework practice and discomfort ratings were recorded on the homework forms.

GBT Session 3. Patients began with a check-in and go-around, reporting on homework tasks. A 15-minute videotape that discussed the neurobiology of OCD and medications was viewed, followed by a brief discussion of this material. The remainder of the 2-hour session was devoted to in vivo and imagined exposure. At this session, patients selected items with higher discomfort ratings (between 50 and 60) on their hierarchies. Again, in-group exposure exercises were modified to address individual symptoms. All of the patients selected homework assignments and received feedback from the group as to whether the tasks chosen were reasonable but challenging. This process was intended to increase individual patients’ problem-solving options and to promote the use of various behavioral techniques. Imparting information and learning from other patients appeared to be beneficial because patients respected the advice that came from someone “in the same boat” whom had had success.

GBT Sessions 4–11. These sessions proceeded in a similar fashion as outlined in Session 3. After a check-in and go-around report from each patient on his or her homework successes and obstacles, the therapist quickly addressed any problems patients had encountered in carrying out their homework assignments. For patients who had not experienced any progress, it was often in this phase that dropout occurred. Although the sense of competition (“If Cheryl can do that, so can I”) was a powerful motivator, patients who had selected inappropriate challenges or had not used exposure long enough to allow habituation felt discouraged as others progressed. Other non-ERP obstacles may also hamper treatment. To prevent dropout, which can discourage other group members, the therapist looked for signs that a patient was repeatedly unsuccessful in employing ERP and used in vivo group exercises to provide an opportunity for a corrective experience. Often, group cohesion had become so developed that patients took more risks to avoid disappointing other group members.

As each session progressed, patients selected items from their hierarchies that evoked increasing levels of distress. By session 8, the most distressing stimulus was introduced to allow time for habituation. The group experience became more interactive, and patients pressed one another to tolerate anxiety. Many patients have reported that they felt a sense of pride and self-worth when they could help fellow patients. This may be another active ingredient of group therapy.

GBT Session 12. The final session was conducted in the same way as those described above, except that the therapist left ample time to address concerns and questions about the end of active treatment. Jan expressed fear that she “wouldn’t be able to do it” on her own without the support of the group. Peter reminded her that she had come so far because of her independent use of the behavioral techniques in her homework and that she had become a primary inspiration for others. The therapist allowed individual expression of parting but did not let the group stray too far off the track. The task of giving closure to the weekly treatment sessions needed attention in order to manage the high level of intimacy in the group. The main focus was on fostering self-instruction and self-efficacy. Group members were asked to comment on the enormous changes they had observed in others while identifying the most helpful elements of the group treatment. Six monthly meeting dates were scheduled, and patients were encouraged to call for help trouble-shooting between sessions as needed.

Family treatment interventions

Another potential strategy for reducing treatment costs and enhancing maintenance of gains is the use of a multiple-family group format that we call multifamily behavioral treatment (MFBT). It is clear that patients’ OCD symptoms can engender extensive family involvement (Calvocoressi et al. 1995) and have adverse effects on family functioning (e.g., Allsopp and Verduyn 1990; Marks et al. 1975). Calvocoressi et al. (1995) reported that 88% of family members participated in some way in OCD symptoms and that greater family participation in symptoms was significantly correlated with family dysfunction and negative attitudes toward the patient. Intervention to address these difficulties might be helpful in overall recovery. To date, however, most the research reported on family treatment for OCD has not directly addressed family involvement in symptoms or family stress and associated costs.

Family response patterns

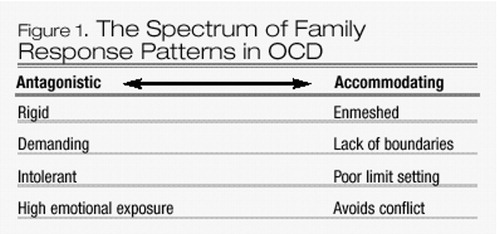

In our clinical experience, family responses to obsessive-compulsive symptoms fall along a continuum of behavioral interactional patterns. This spectrum can be visualized as having two polar opposites of either totally giving in to, and even assisting in, the symptomatic behavior or unequivocally opposing the behavior. The two most extreme positions are depicted in Figure 1.

A third type of response pattern that is commonly seen is a split family. In this case, the family members (usually parents) are divided in their reactions to the symptoms, with one family member at the antagonistic end and one at the enmeshed, accommodating end of the response continuum. Another common scenario occurs when family members oscillate in their responses, swinging from one end of the spectrum to the other as frustration and anger toward the patient and his or her symptoms escalate. Family members, usually out of frustration that “nothing seems to work,” become inconsistent by trying to participate in the rituals and then trying to cut them off. It should be kept in mind that most families lie somewhere in the middle of the continuum. Regardless of the family response pattern, both patients and their families often feel confused, angry, and anxious.

Relatives are often uncertain whether the prolonged rituals and constant need for reassurance are really part of an illness or are willful rebelliousness and demands for attention and control. Such perceptions may influence the ways in which family members respond to or try to cope with the symptoms of OCD. In turn, a transactional coping process unfolds in which family responses may facilitate or extinguish obsessive-compulsive symptoms, thereby affecting the patients’ functioning. Preoccupied with the needs of the patient and feeling blamed and burdened, family members may pull away from their usual social contacts or work commitments and become increasingly socially isolated themselves. Patients with OCD may become more impaired if it seems that less is expected of them, but hostile criticism and unrealistic expectations from relatives can also evoke undue anxiety and perpetuate impairment.

Expressed emotion

Another area of interest in family research that aptly extends to understanding transactional coping processes in OCD families is the concept of expressed emotion. Expressed emotion appears to be particularly applicable to our understanding of and treatment approach with OCD patients and their families. Based on British studies of families coping with a member diagnosed with schizophrenia (see Brown et al. 1972; Falloon et al. 1984), expressed emotion refers to relatives’ critical, hostile, or overinvolved attitudes toward the diagnosed patient. Numerous studies have consistently reported that high expressed emotion is significantly correlated with high rates of relapse. Studies have reported on the association of expressed emotion with relapse mainly for patients with schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar manic depression. Expressed emotion has been found to predict outcome independent of illness severity (see Hooley et al. 1986), supporting the contention that criticism and emotional overinvolvement are not merely responses to severe symptoms in patients. Expressed emotion has been less well studied in OCD. Hibbs et al. (1991) noted that high expressed emotion was more frequent among parents of children with OCD or conduct disorder than among control subjects. Leonard et al. (1993) reported a 2–7 year follow-up study of 54 children and adolescents with OCD in which high parental expressed emotion was the second strongest predictor of long-term global functioning, superceded only by response to clomipramine at 5 weeks. Although not a direct study of expressed emotion, a study with similar findings was reported by Steketee (1993a), who found that negative family interactions (e.g., anger, criticism) and relatives’ beliefs that the patient with OCD was malingering predicted fewer gains at 9-month follow-up.

Family interventions for other disorders

Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of family education and treatment in the outcome of schizophrenia and affective disorders (Brown et al. 1972; Falloon et al. 1984; Miller et al. 1986); this may also hold true in OCD. Family psychoeducation and communication training approaches have demonstrated that patients from families whose expressed emotion levels were reduced from high to low after treatment were considerably less likely to relapse than were those from families who remained high on expressed emotion (Anderson et al. 1986; Falloon et al. 1984; Hogarty et al. 1986; Leff et al. 1982; McFarlane et al. 1995). In addition, McFarlane et al. (1995) found that patients with schizophrenia who received multifamily treatment had lower rates of relapse than did those in single-family treatment. There are few data on behaviorally oriented multifamily groups. However, Falloon et al. (1981) were among those to report on such a treatment. They noted a reduction in critical comments and overinvolvement among family members after 25 sessions of a multifamily group for patients with schizophrenia. Applications of family interventions to OCD are not well studied.

Our clinical experience suggests that the family support system often plays a critical role in the prognosis and outcome of treatment. This may be particularly true for those patients who fail to respond to standard individual behavioral treatment and pharmacologic interventions. With regard to family involvement in treatment, Hafner (1982) reported several cases in which poor marital relationships appeared to interfere with the benefits from behavioral treatment for OCD outpatients. He noted that such patients showed improvement when spouses participated in the behavioral treatment process (Cobb et al. 1980; Hafner 1992). Similar benefits were also evident in case studies of parental involvement in behavioral treatment of children (e.g., Dalton 1983), adolescents, and adults (Hafner et al. 1981; Hoover and Insel 1984). Mehta (1990) reported that involving family members in behavioral treatment for 30 patients in India led to significantly greater gains in OCD symptoms, mood state, and social and occupational functioning compared with unassisted treatment. At follow-up, family treatment patients showed continued improvement, whereas patients treated individually lost some gains, making the outcome gap even wider. Patients with family members who were not anxious and who were firm were more successful than patients who had anxious and inconsistent family members, especially ones who engaged in argument and ridicule.

Correspondingly, our own work with family group interventions has led us to believe that special strategies are needed to alter such antagonistic communication styles. Two uncontrolled trials of family treatment have included efforts to reduce relatives’ involvement in OCD symptoms. An inpatient treatment program in Great Britain emphasized self-treatment and teaching relatives to assist in the therapy program for inpatients with various diagnoses, including OCD (Thornicroft et al. 1991). Individual behavior therapy was combined with a family component that focused on training relatives to monitor patient behavior and encourage self-exposure in a noncritical manner. Relatives practiced under the therapist’s supervision on the ward. This treatment program led to a 45% decrease in symptoms at discharge and a 60% decrease at 6-month follow-up, with concomitant improvement in functioning. Such results indicated excellent success for this severe inpatient population, who scored in the extreme range on disability from OCD symptoms.

Like group behavioral treatment, MFBT may also be a cost-effective and efficacious alternative to individual treatment for OCD. A pilot study of 19 patients in our center examined the effects of 10–12 sessions of family treatment conducted in groups of 6–8 families that included a mixture of spouses, partners, parents, and others in daily contact with the patient (Van Noppen et al. 1996). Treatment included psychoeducation, family exchange of information about OCD symptoms and coping strategies, exposure with modeling and response prevention, and family communication skills training, including family behavioral contracting for homework assignments. Good effects were observed after treatment and 1 year later: Y-BOCS scores improved by an average of 9–10 points and 58% of MFBT patients were clinically significantly improved, somewhat more than occurred with group behavioral treatment (43%). Significant improvements in disability scores were also evident. In addition, most scales assessing family functioning showed improvement posttest, although significant differences were not evident at follow-up on a smaller sample. The Family Accommodation Scale for OCD (FAS-OCD; Calvocoressi et al. 1995) was used to assess family involvement in rituals.

Support groups with psychoeducational foci for patients and family members may provide a useful avenue for family assistance in the treatment of OCD (Black and Blum 1992; Cooper 1993; Tynes et al. 1992). Psychoeducational group goals usually include improving self-esteem, sharing feelings and experiences, accepting patients’ realistic limitations, and learning strategies for coping with OCD symptoms. Participants have reported good satisfaction with psychoeducational groups, but no outcome data are available regarding group effects on patient symptoms.

Our MFBT uses interventions that are specifically aimed at reducing obsessive-compulsive symptoms as well as changing transactional patterns of communication between family members that may facilitate these symptoms. The MFBT incorporates psychoeducation, communication skills training, increased problem solving, boundary clarification, social learning, and rehearsal of ERP with therapist and participant modeling.

Case example: multifamily behavioral treatment

Information gathering. Kim, a 28-year-old mother of a 2-year-old daughter, described symptoms of OCD that dated back to her childhood. She sought treatment after severe exacerbation of her symptoms during her first pregnancy. Kim was referred for MFBT after a partial response to an SSRI and a low dose of a neuroleptic and 6 months of unsuccessful psychotherapy elsewhere. Kim reported that her primary fears had to do with extreme worry that she would contract cancer from various “substances,” even when they could not be seen. These included detergents, chemicals (e.g., asbestos, lawn service truck), gasoline, “oil spills” on the sand at the beach, batteries, exhaust, make-up, and cigarettes. In response to these fears, she was washing her hands more than 100 times a day and avoiding any situation or object that would trigger the worry about cancer. In addition, out of fear of “additives,” she had restricted her diet to only one brand of natural ice cream and natural granola. Kim also spoke about feeling as if she “had to sit with clenched fists to be sure” that she wasn’t making blasphemous gestures to God. She had given up on doing laundry, grocery shopping, and cooking because every task “took too long.” Kim described piles of unwashed laundry in her basement, some more than 3 years old, that were starting mold because of her avoidance. When asked about her husband’s response, Kim said that he would surrender to her requests in order to “keep the peace.” She involved him in extensive reassurance-seeking rituals, usually more than 50 times a day, although she stated that she wanted to stop her “strange behaviors” because it was tearing her family apart. However, Kim “really believed” she could die from the “cancer germs.” She had begun to involve her daughter, Lilly, by washing Lilly’s hands so frequently that she had protested against it. Kim’s husband, Joe, had also given up on trying to get Kim to cook. Sneaking food into the house created such an uproar that he resorted to taking Lilly to his mother’s house for most suppers.

Joe had viewed Kim’s worries as just part of her personality. Joe worked as a salesman and Kim was offered a good job as a secretary at a local company. Shortly after they bought their own home, Mary, Kim’s sister with whom she was very close, was diagnosed with cancer. To make it easier to receive chemotherapy, Kim insisted that Mary move in with her and Joe. Kim was wonderful to Mary during this time, sharing everything she owned. Mary’s cancer remitted and she moved back to live with their mother. Two years later, Kim became pregnant and began to express fears that she and the fetus would contract cancer from Mary or anything Mary had touched. Because Mary had been living in Kim’s house, nearly everything seemed “contaminated.” To avoid conflict, Joe went along with all of Kim’s requests, no matter how extreme. For example, he complied with her rules of taking specific routes to the grocery store, so as not to drive by “asbestos-contaminated” areas; buying dairy items at the back of the case so they weren’t exposed to “radiation”; not using certain dishes, spices, or foods that had been used by Mary; and not sitting on certain “clean” chairs.

Kim and Joe appeared at the second of two information-gathering sessions, eager to learn more about OCD and how to handle it. Joe spoke of feeling as though “Kim’s demands were controlling everything.” He had given up trying to convince her not to be afraid because nothing seemed to work. Joe reported that “lately, Kim was going too far by involving Lilly.” He went on to report that Lilly was not allowed to go to his mother’s house if anyone in the neighborhood had had their lawn treated with chemicals, which involved a lengthy interrogation process. Lilly’s clothes were changed at least 5 times a day, $25.00 a week was being spent on paper towels, and family activities were usually abandoned prematurely because of Kim’s demands to go home to wash and shower. Joe’s strategy had been to give in, but he felt that Kim’s behavior had gotten “way out of hand” and that he did not know what to do about it. The therapists spoke about the MFBT offering this kind of help to family members. Besides problem solving with other families dealing with OCD, Joe would learn a specific technique, behavioral contracting, that would help him begin to set some limits on his participation in Kim’s compulsions. Also, the more that Kim and Joe could learn about OCD, the more they would be able to control it. Hierarchies were established for fears of contamination-cancer from Kim’s sister and from chemicals. One such hierarchy is listed in Table 3.

MFBT Session 1. Kim and Joe were asked to read Chapters 1–4 in When Once is Not Enough before the group began. At the outset of the MFBT group, anticipatory anxiety ran high. Kim and Joe were among a total of seven couples/families. Some families arrived very early to be certain they were not late, whereas others, arriving late, rushed through the door with apologies, reporting that the patient had trouble getting to places on time because of obsessions and compulsions. The initial anxiety about the group was alleviated by providing structure, especially at this first session. However, the therapists also allowed room for individual expression that would collectively determine the “climate” of the group with regard to blame, responsibility, overprotection, overinvolvement, distance, impotence, and denial. The therapists observed the level of interaction and content as well as seating choices that could reveal alliances, conflicts, and level of trust within the group. Each person was asked to introduce him- or herself and indicate what he or she hoped to get out of the group. This facilitated participation and began the foundation for trust and group cohesiveness. Questions asked included, “What should I do when my daughter is in the shower for 3 hours? Can that really be OCD?”; “How do other families deal with the rituals?”; “What is OCD?”; and “How can each of us cope with it effectively?” A quick review of the ground rules clarified group expectations about the time frame of the group, the meeting place, confidentiality, and notification of absence from the group. A handout entitled “What is OCD?” that provided a definition of obsessions and compulsions and described theories of etiology, course of illness, common coexisting disorders, and treatment was distributed as well as the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist. The information was reviewed and the checklist served as a springboard for the group to disclose the obsessive-compulsive symptoms and behaviors that they typically hid in shame. As usual, there was great relief that others had similar thoughts and experiences. Kim, for example, said “Wow, you do that too! I thought I was the only one who won’t let anyone else sit in my chair!” As family members heard others describe symptoms and feelings identical to those they have struggled with for many years, they began to realize that OCD was a real disorder beyond the patient’s control. The group also provided the first real opportunity for several family members to learn about the content of the patient’s obsessions and the extent of the rituals.

Families enthusiastically compared experiences. Joe was relieved to hear other spouses express helplessness and how they would surrender “to keep the peace.” Families talked about the bizarre symptoms in an atmosphere with little social stigma. Fears that maybe their loved one was going crazy seemed quieted by meeting others with OCD who were “normal people.”

The leaders left time for patients to select their ERP homework challenges. Kim chose to begin with the items lowest on her hierarchies. The session formally ended after homework forms were distributed and the therapists explained that this first week would be a trial time to begin to practice ERP. If patients did not sense that their distress was decreasing, they were encouraged to modify the exposure challenge and stay with one item until the discomfort diminished. Family members were reminded that one of the goals of the MFBT was to learn to be involved in the OCD as little as possible except in life-threatening or dangerous situations. Family members were instructed to keep their involvement to a minimum but not to make any drastic changes in their responses to the demands of OCD until they learned to use behavioral contracting. All families and patients were asked to finish reading When Once is Not Enough before the next session.

MFBT Session 2. The second session began with a review of what had been covered and accomplished the previous week. The leaders then asked whether anyone had any thoughts, questions, or feelings that they wanted to talk about. This discussion, which was brief and to the point, provided continuity between sessions, allowed members to warm up, and conveyed a sense of respect and appreciation for members’ concerns. Each patient reported on the homework he or she had completed during the week, and the therapists collected homework forms, verifying that patients completed them as assigned. Therapists provided positive reinforcement to patients who had completed the form and performed the exposure, thereby modeling positive feedback to the group. Kim reported that she was unsure whether she was doing the homework correctly but that she had had success with holding a cigarette pack. She said that her discomfort level decreased to about 20 in all of these situations. Joe said he felt Kim should do the homework alone and asked what he should do if she wants him present “for security.” Some group members made suggestions that if it helped Kim to get started with the exposure, it was probably okay as long as he did not encourage her rituals.

Most of this second session involved the description of behavioral therapy and ERP techniques. Group leaders asked members what they thought behavioral therapy meant and explained that behavioral therapy provides tools for changing unwanted behaviors without analyzing the childhood history and meaning of the behaviors in detail. Next, the sequence of obsessions and compulsions was reviewed, explaining how a trigger or cue evoked an obsession, which led to feelings of anxiety and the urge to ritualize. The techniques of direct and imagined ERP in vivo and imaginal exposure were described. As each patient selected his or her homework, the group leader translated the task into a form that could be rehearsed in the group, and the therapist and other group members participated in the exposure challenge. Kim was asked to touch the doorknobs in the room along with all the other group members. This was difficult for other patients who had contamination fears for other reasons. Kim commented that it helped to see so many people unaffected by the task and that this observation made her question her own behavior and beliefs. Joe spoke about all the hours they had wasted talking about the irrationality of Kim’s beliefs and how these discussions would lead to a point of desperation at which he would shout at her and call her “crazy”: “Kim would end up crying, but at least it would stop the questioning.”

At the end of the second session, the therapists instructed patients to continue the exposure from that day’s session and add any other homework items to be practiced at least 1 hour a day, preferably all at one time rather than split into segments. Patients were reminded not to leave the exposure situation until their anxiety had declined noticeably and to record their distress levels on their homework form. Joe asked what he should do if Kim asked him to buy her more paper towels or to bathe Lilly “for the third time?” The therapists acknowledged that all families were eager to have these dilemmas resolved and that they would be getting to this more specifically at the next session. Families were encouraged to use what they had learned so far to modify their responses and to limit their involvement in rituals while communicating an appreciation for how hard it is for the patients to “just stop.”

MFBT Session 3. The group began in its usual way, with each patient reporting on his or her homework task results. Members engaged in troubleshooting for problems that they were experiencing with the ERP homework and the homework forms. Kim reported that she continued to make headway but felt that so many things bothered her that she was not sure she would ever “get over” her OCD. Joe added that he had noticed a big improvement in Kim’s outlook and that she seemed more willing to take risks. For example, they had gone out to eat pizza for the first time in 8 months, and Kim had stepped on a cigarette butt, driven behind a bus, touched the doorknobs, and sat with her hands open without performing any rituals. The group was tremendously supportive of Kim, but in spite of this support she asked how, if OCD is a neurobiologic disorder, she would be able to change it. Others nodded, and one insightful spouse responded, “it’s just as our therapist said: changing behavior can change thoughts and feelings. Look, it’s already happening for you.”

At this session, the therapists presented a brief videotaped lecture on the neurobiology of OCD that provided information on medication and the interplay of behavioral therapy with biologic processes in the treatment of OCD. After a discussion of this tape, the therapists asked each patient to select exposure items with a discomfort level of approximately 50–60. After about an hour of in vivo or imaginal exposure, the group began to discuss the “Guidelines For Living with OCD” described by Van Noppen and colleagues in their pamphlet, “Learning to Live With OCD.” These guidelines included the following:

| • | Learn to recognize the signals that indicate a person is having problems | ||||

| • | Modify expectations during stressful times | ||||

| • | Measure progress according to the person’s level of functioning | ||||

| • | Don’t make day-to-day comparisons | ||||

| • | Give recognition for “small” improvements | ||||

| • | Create a strong, supportive home environment | ||||

| • | Keep communication clear and simple | ||||

| • | Stick to a behavioral contract | ||||

| • | Set limits, yet be sensitive to the person’s mood | ||||

| • | Keep your family routine “normal” | ||||

| • | Use humor | ||||

| • | Support the person’s medication regimen | ||||

| • | Make separate time for other family members | ||||

| • | Be flexible | ||||

Group members took turns reading aloud and the therapists asked the families which of the five family responses best described them. These responses include

| 1. | Families that assist with rituals to keep the peace | ||||

| 2. | Families that do not participate in rituals but allow them to occur | ||||

| 3. | Families that refuse to acknowledge or allow the compulsions in their presence | ||||

| 4. | Families that are split in their responses—some members always give in, whereas others refuse to do so | ||||

| 5. | Families in which members swing from one extreme to the other | ||||

This discussion promoted insight into family response patterns and the impact of those responses on the patient. Joe spoke about the accommodating pattern as fitting for him, yet he started to see that he also oscillated at times out of frustration. He spoke about the time he got so angry because Kim wouldn’t get out of the shower that he shut off the hot water. She continued to shower anyway, in the cold water, so he turned off all the water in the house. This resulted in a screaming battle that woke Lilly and made her cry, so he turned the water back on. Other families related to Joe’s story, adding that it was hard to be consistent or to really follow through on threats. Kim reported that she had given this pamphlet to her mother and siblings to read and that “for the first time they seemed to understand that my fears weren’t personal feelings about them.”

Kim and the other patients reassessed their behavioral homework task with the family guidelines in mind and added another challenge. Members told Joe that he should not blame himself for “helping” because he was doing the best that he could, even more so because he had not known what he was dealing with. Now, with education and some tools, there was hope.

MFBT Session 4. The first three sessions had provided patients and families with a clearer understanding of OCD. The next step was to learn how to cope more productively with the symptoms as a family using cognitive and behavioral techniques. This fourth session was designed to prepare the families for family contracting, which forms the essence of family collaboration in the treatment of OCD and would be the focus of upcoming sessions. As usual, the meeting began with a review of homework. Kim and Joe described being discouraged because they had gone away for the weekend and Kim had been afraid that their condo was sprayed with pesticide. She had stayed in the same clothes all weekend, would not let Joe bring their suitcases out of the car, would not allow Lilly to play on the floor, and felt that she was “back to base 1.” Joe brought to the session some of the clothes that they had worn, despite Kim’s pleas not to do so; he knew he had to be firmer and insisted despite their bickering. The group gave Joe positive feedback for doing this and confronted him about his tendency to give in too much. The therapists asked that these items be used in the session during the behavioral contracting.

The therapists introduced the concept of behavioral contracting by asking the group what they thought was meant by this term. The therapists then outlined the critical concepts in behavioral contracting: 1) realistic expectations on the part of patient and family are clearly defined; 2) the family learns how to be supportive in ways that are therapeutic to the patient; 3) the patient is given responsibility for therapy that enhances his or her sense of control, motivation, and confidence; and 4) limits of responsibility are clarified and family members are redirected to get involved in their own lives again.

The group discussed Kim’s exposure homework and considered what Joe should do to be supportive but not facilitate the OCD. Kim and Joe decided they would target Kim’s need for reassurance, which had decreased but was still out of hand. This led to a discussion of what was reasonable with regard to reassurance. One father asked, “But don’t we all need reassurance?” One spouse responded that the kind of reassurance people with OCD ask for may seem reasonable at times, but the repetitive questioning and the urgency of the need for certainty were not “normal.” Others agreed and added that in some cases the questions did not have absolute answers, and in other cases the patient already knew the answer to the question. All of the families identified the process of giving reassurance as “futile,” “exhausting,” and “frustrating.” Patients in the group expressed feelings of shame about their behavior.

One of the therapists led Kim and Joe through a detailed negotiation process to arrive at an agreement as to how Joe should respond to Kim’s requests for reassurance. Kim gave Joe permission to label her questions as OCD and to remind her that she knows how he would answer the “OCD question.” If she persisted, he was to suggest that she put the question on hold, even though it seemed urgent, and if it still bothered her they could talk about it later. If Kim continued to persist, Joe was to remind her again that this was a reassurance question and that he knew what she was going through but that it would not help to talk about it. Kim agreed that at this point Joe should suggest that she do something else to distract herself because she always felt better over time. If this did not work and the requests became very unreasonable, Joe was to leave the room, or the house if necessary, to remove himself from the situation. If Kim became very agitated, Joe would answer her once and only once.

All of the families left the session with a behavioral contract to practice and homework forms to record the progress. As had been done in previous sessions, each patient committed to performing individual exposure homework as well as the family contract. Family members were directed to get involved in their own lives again.

MFBT Sessions 5–11. As usual, each of these sessions began with discussion of exposure homework and behavioral contract. During these 2-hour sessions, the group practiced in vivo and imaginal ERP, family contracting, self-monitoring of distress levels, and homework planning. Family responses to OCD symptoms were discussed in greater detail, and greater disclosure about symptoms emerged. Group interaction became highly personalized as families described the interpersonal conflicts that arose in their attempts to manage the obsessive-compulsive symptoms.