Clinical Ethics Teaching in Psychiatric Supervision

Abstract

Supervision of psychiatric residents provides a natural context for clinical ethics teaching. In this article, the authors discuss the need for ethics education in psychiatry residencies and describe how the special attributes of supervision allow for optimal ethics training for psychiatry residents in their everyday encounters with ethical problems. Ethical decision making in clinical settings is briefly reviewed, and a six-step strategy for clinical ethics training in psychiatric supervision is outlined. The value of the clinical ethics supervisory strategy for teaching and patient care is illustrated through four case examples.

Ethics is not added to a clinical case by injecting into it new facts or by imposing on it some alien principles and values. The ethics of any case arises out of the facts and values imbedded in the case itself. Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade (1)

Ethics is not just a set of visceral sensations. McIlhenney and Pellegrino (2)

Psychiatry, like the rest of medicine, is in part the practice of applied ethics. . . . Each day the resident must struggle with existential questions in the emergency room, in the clinic, on the wards. The questions are not simply idle exercises but must be answered; the answers intimately affect the lives of the patients. Yager (3)

Psychiatric resident supervision provides a natural context for clinical ethics teaching. Supervision is case-based, contextual, exploratory, responsive, knowledge-driven, judgment-oriented, and evaluative. Ideally, clinical ethics teaching also possesses all of these features. Clinical ethics is an emerging academic discipline that seeks to improve patient care by incorporating the knowledge of ethics into everyday medical practice, enhancing the clinical judgment of physicians (1, 4).

Describing why these attributes of supervision are so valuable to clinical ethics teaching is the first aim of this article. The second aim is to present a six-step approach to clinical ethics teaching in psychiatric supervision, with examples of its use.

The need for ethics training in residency

Caring for patients is an intrinsically ethical activity, and it is widely agreed that ethics training is an important component of a psychiatry resident’s education (3–25). Ethics education provides knowledge, cognitive tools, and communication and behavioral skills that are useful to physicians and patients in clinical settings (2, 10, 15, 26, 27). Moreover, trainees are very interested in learning more about ethics as it applies to psychiatric practice, as was demonstrated in two studies involving psychiatry residents.

Roberts et al. found that 92% of 181 psychiatry residents at 10 training programs believed ethics training to be helpful in responding to ethical dilemmas in patient care (17). A majority of these residents wanted to learn more about 19 specific ethics topics. Coverdale et al. surveyed chief residents at psychiatry training programs across the United States who indicated interest in a number of ethics areas as well (8). Concern about ethical dilemmas created by new economic pressures in mental health care (28–29) and controversy about recent cases of ethical misconduct in psychiatric practice and research suggest that ethics curricula will continue to be important in postgraduate psychiatric education.

Curiously, physicians often do not receive much formal ethics teaching during residency (12, 15, 17). Seventy-six percent of 181 residents in the Roberts et al. study reported facing an ethical dilemma in residency for which they felt unprepared, and 46% reported having received no formal ethics training during residency (17). Similarly, Coverdale et al. found that 40% of 121 psychiatry residencies did not offer a formal ethics curriculum (8). These results are disturbing, as ethics training in medical schools also is not ubiquitous—one-third of residents in the Roberts et al. study could not recall receiving ethics education as medical students. Thus, it cannot be assumed that all psychiatrists will have been formally trained in ethics, even modestly, during their medical education. As a consequence, there is an imperative to develop rigorous, useful ethics curricula in psychiatry residency programs in the United States now (6, 8, 11, 17, 19, 21, 24, 28, 30).

While it has become clear that ethics should be taught to psychiatrists, the characteristics of effective ethics training have been less certain. Controversy surrounds the question of which curricular interventions have the greatest and most enduring value (9, 14, 15, 26, 27, 31). This issue is particularly true during residency education, a period in which curricular development and innovation are extremely difficult (7–9, 12, 15, 17, 27–33).

In addition, with a few valuable exceptions (7, 22, 23), models for understanding psychiatric ethical issues have been relatively neglected in the psychiatric literature. The conceptual distinction between ethical and legal aspects of psychiatry also has been underrecognized, with negative repercussions for ethics curriculum development. Moreover, studies of the ethical issues in psychiatric practice and research have generated many new questions that have not yet been addressed empirically (34–36). Much remains to be understood about the task of teaching ethics in psychiatry.

Experience and some evidence suggest, however, that intensive, systematic approaches to clinical ethics training that build upon a foundation of knowledge and help to develop practical judgment may be especially worthwhile for physicians (1, 2, 4, 10, 12, 15, 17, 29). Residents themselves prefer training methods and topics that integrate clinically relevant information on ethics with everyday medical activities and decision making (12, 17, 31). For psychiatry residents, individual supervision that extends beyond didactic teaching and includes a sustained and organized focus on ethics issues thus offers an ideal setting for ethics education.

Psychiatric supervision and clinical ethics teaching

Several aspects of supervision make it particularly suited to clinical ethics teaching. The first is that it is case-based. Supervision focuses on the care of individual patients; clinical ethics focuses on the ethical issues arising in the care of individual patients. The intrinsic work of supervision—evaluation of patient symptoms and signs, formulation of diagnostic issues, and construction of therapeutic plans—lays the groundwork for exploring the ethical dimensions of a case (1, 4, 10).

Second, supervision is contextual. Supervision occurs on wards, in clinics, in therapy offices, and in emergency rooms. Supervisors at these sites are optimally attuned to the salient clinical issues, the real constraints on resident decisions, and the influences of the treatment milieu and institutional culture in each of these training settings. This contextual quality of supervision is helpful to ethics teaching for two reasons.

The first reason is that patient-care decisions, which may be complicated by context-related problems, are often identified as ethical dilemmas, a phenomenon that may be best clarified by residents in supervision. For example, a resident may grapple with what might appear to an outsider to be autonomy issues involving an “uncooperative” patient when the real problem is lack of access to psychiatric services, interfering with patient compliance. The supervisor can help the resident to see how the provision of clinical care within a particular system thus emerges as one kind of ethical conflict when it may, in fact, be another type of problem.

The second reason is that supervision itself becomes an important part of each training context. Consequently, ethics teaching in supervision is immediate, pervasive, and meaningful for the resident. This level of attention to ethical issues, taken not in isolation but in their real clinical context, has been a highly touted but elusive goal of medical ethics education (9). For these reasons, psychiatric supervision provides an excellent opportunity for understanding and addressing the ethical dimensions of patient care.

Third, supervision is a uniquely responsive and exploratory educational experience in residency training (21, 37). It is a collaborative relationship with two aims: the professional development of the resident and the optimal care of his or her patients. Ideally, through supervision, faculty explore and respond to the trainee’s concerns in a manner that is genuinely helpful, promotes growth, reduces defensiveness, and encourages self-understanding. Supervision also provides information and support, appropriately addressing the troubling emotions, stresses, and challenges experienced by the resident (12, 38). These qualities of supervision make for a constructive milieu in which to discuss difficult clinical ethical issues. Rather than simply reacting in challenging clinical situations, residents may carefully consider ethical problems with their supervisors, think about their choices and concerns, and then deliberately decide upon their actions. Good supervision thus promotes better individual ethical decisions and improves professional conduct by residents.

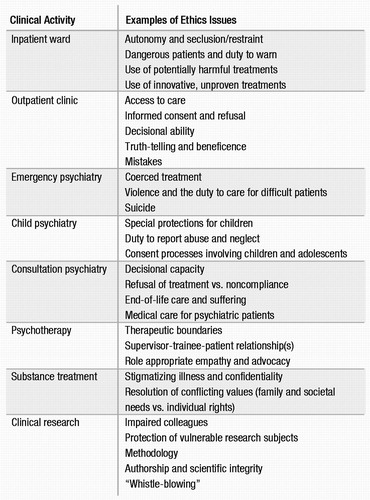

Finally, supervision is knowledge-driven, judgment-oriented, and evaluative. It offers an opportunity to gather information, reach clinical decisions, and learn from patient outcomes over time (25, 37). Supervision sessions provide a structured occasion to reflect upon one’s own perceptions and behavior in caring for patients (25). That is to say, supervision helps residents learn sound clinical practices and careful self-observation. In addition, as the clinical and ethical problems encountered by residents shift emphasis (Table 1), their supervision also will evolve in content and meaning. The tasks of supervision heel closely to the clinical sophistication and professional maturation of residents, prompting both supervisors and supervisees to learn. The sum of a resident’s experiences in supervision throughout their training thus constitutes a kind of apprenticeship in decision making and practical judgment. Because judgment encompasses not only clinical actions but also self-knowledge, self-evaluation, and professional conduct, the work of psychiatric supervision and of ethics training overlaps.

Supervision is an educational experience in psychiatric residencies in which ethical issues arise indigenously and clinical ethics teaching may be particularly compelling.

Clinical ethics: decision-making strategy

Valuable models for ethical reflection in clinical settings have been described by Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade (1, 4); by Beauchamp and Childress (39); by Hundert (22); by Sadler and Hulgus (23); and others. Each of these models offers a conceptual scheme for organizing the many complex, perplexing, and potentially incongruent aspects of a clinical case. The clinical ethics decision-making scheme proposed by Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade (1, 4) is presented here because, of all these models, it places the greatest emphasis on the clarification of clinical issues as the initial work of ethical reflection in patient care. It capitalizes on the clinical strengths of supervisors, and, as a model, it fits very naturally with the usual tasks of clinical supervision. Other conceptual schemes are very helpful and are not mutually exclusive, however, and can easily be incorporated within the clinical ethics supervisory approach we propose.

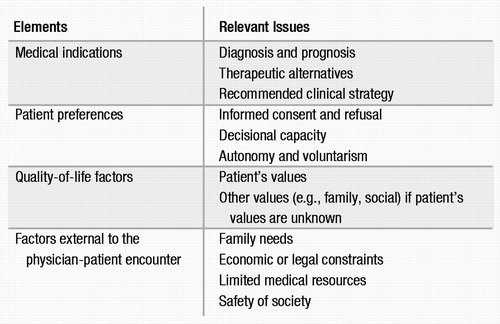

The original strategy for clinical ethical decision making constructed by Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade (1, 4) involves four areas of consideration (Table 2). The first consideration always relates to the medical indications in the case. Medical indications include the diagnosis, prognosis, therapeutic alternatives, and, ultimately, the physician’s recommendation or care plan. The second consideration chronologically, but of great significance in clinical actions, is the patient’s preferences. The patient’s informed and reasoned choice is of vital concern in clinical ethical decision making. The next consideration, quality-of-life factors, may take precedence when patient preferences are unknown or are unknowable, but these factors ordinarily play a lesser role in determining clinical ethical decisions. Finally, other relevant factors outside the immediate physician-patient encounter may influence clinical ethical decisions. Examples include limited medical resources for treatment of serious, chronic mental illnesses or for organ transplantation or other interventions; legal constraints of physicians with respect to coerced treatment or to patient confidentiality; and economic obstacles of patients seeking elective surgery, innovative pharmacotherapies, or other costly care. These factors typically set the conditions under which clinical ethical decisions must be made. Taken together, these four areas of consideration create a systematic but flexible framework for ethical decision making in clinical settings.

Approach to clinical ethics teaching in psychiatric supervision

We have developed a clinical ethics approach to psychiatric resident supervision that integrates direct teaching, ethical reflection, and clinical decision making. It is a six-step strategy (Table 3), which is readily assimilated into individual resident supervision already occurring in a variety of psychiatric training contexts (Table 1). In this section, we describe how faculty may employ the supervisory method in their work with residents, and in the next we provide four illustrations of its use.

1. Define clinical decisions

Ethics teaching in psychiatry supervision begins with the task of helping the resident to define the issues and decisions involved in a clinical case. Guiding the resident as he or she develops a list of clinical problems, arrives at a diagnosis, and determines the goal(s) of treatment is a traditional activity in psychiatric supervision and represents the first step in clinical ethics decision making. On the ward, for instance, when considering whether to prescribe innovative neuroleptics or to perform electroconvulsive therapy, the resident should first decide whether this is a reasonable choice given the patient’s diagnosed condition. It is unwarranted to debate broad philosophical principles, as too often happens in ethics discussions when basic medical concerns and clinical indications have not yet been clarified. By defining the clinical decisions involved in a case as the initial step of an ethics discussion, the supervisor and resident emphasize competent clinical care as the foundation of ethical action.

2. Identify clinical ethical elements and conflicts

The supervisor and the resident should next identify the ethical elements and conflicts present in a clinical situation. Clinical ethical elements may encompass those described in the original clinical ethics decision-making strategy, as depicted in Table 2: medical indications and imperatives; patient preferences, values, background, and decisional capacity; quality-of-life considerations; and other relevant factors, such as family concerns, cultural contributions, and legal and economic parameters. Other models of medical ethics such as the principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice described by Beauchamp and Childress (39) or the core aspects of the clinical encounter encompassing knowledge, ethics, and pragmatism in the context of a larger biopsychosocial approach described by Sadler and Hulgus (23) provide useful ways of articulating the ethical elements present in a patient case. Hundert’s technique (22) for developing “lists of the conflicting values” also is an excellent exercise for supervisors and trainees in this step.

This second step draws upon the knowledge and experience of both the supervisor and the resident. While supervisors may find it helpful to familiarize themselves with one or more conceptual models of medical ethics, they need not be formal experts in ethics. Past encounters with clinical, ethical, and legal dilemmas in psychiatric practice, and their outcomes, represent an excellent in situ ethics education for supervisors. Residents also may have some knowledge of ethics derived from medical school and residency curricula, readings, and personal experience. In this step, the supervisor can help the resident to apply such knowledge in very real situations.

Beyond the supervisor’s understanding of ethics is the supervisor’s understanding of residents themselves. Supervisors ideally will remain mindful of the process of professional development during psychiatry training and will be attentive to the specific concerns of supervisees when considering ethical problems. Although clinical ethics discussions should not resemble psychotherapy, some understanding of the psychological and interpersonal determinants involved in the case can be helpful in establishing how ethical dilemmas are experienced. As in supervisory sessions focused on countertransference issues, a limited exploration of the resident’s feelings about the situation may be necessary before it is possible to approach the patient’s care in a clear-sighted manner (18). Thus, the success of this step depends upon the supervisor’s sensitivity to ethical issues, cognizance of the resident’s circumstance and perceptions, and willingness to explore the interplay between ethics and emotions explicitly. By illuminating the ethical aspects of a patient’s case and by identifying points of conflict in this second step, supervisors may help their residents to better understand how clinical, personal, and ethical elements fit together to inform therapeutic decisions.

3. Gather information and consult

The supervisor and the resident next should gather information and expertise. For many ethical problems, supervisors will have developed a reasonable approach based on previous cases, and residents will already have obtained the data and knowledge needed to act in the clinical situation. In these instances, the process of gathering information may appropriately remain between supervisor and resident.

More challenging, and more instructive, is the situation in which the supervisor and the resident together must seek additional resources needed for optimal patient care. This collaboration between supervisor and trainee serves several purposes (Table 4). First, it enriches the understanding of the clinical and ethical dimensions of a patient’s case. Second, it helps supervisors and residents alike to develop their current knowledge and skills and may prevent clinical and ethical mistakes. Third, observation of a respected role model as he or she learns is a salient educational event for residents (12, 15). The supervisor’s commitment to collecting information and expertise demonstrates to residents that clinical work entails curiosity and resourcefulness throughout one’s career. Fourth, it affirms for residents that approaching clinical ethical decisions and, ultimately, making sound clinical judgments are intrinsically collaborative, process-oriented activities. They are not merely intuition, opinion, or the simple repetition of former actions. For these reasons, this third step of a supervisory approach to clinical ethical teaching is crucial.

Two kinds of resources are usually helpful at this stage: people and written documents. Patients and families often can provide additional history needed to clarify the clinical and ethical issues present. Through the process of talking with patients and their families, medical indications and patient preferences may also become more certain, simplifying clinical ethical decisions. While remaining cognizant of confidentiality boundaries, supervisors and residents may consider a variety of other “people resources,” such as patient-care staff, faculty, peers, psychologists and social workers, institutional advisers (e.g., ethics consultants, attorneys, clergy, or others), and, if needed, outside experts. In all of these discussions, supervisors and residents learn incrementally and collect knowledge useful in clinical decisions.

Written documents of four kinds also may be especially informative for supervisors and residents in this step. Searching the medical, psychiatric, and ethics literatures may yield insights about important clinical indications and standards, current research efforts, resources to improve patients’ quality of life despite illness, and others’ experiences with similar clinical ethical dilemmas (40, 41). Reviewing patient records, like gathering additional history from patients directly, is a standard practice that often is helpful. Referring to formal codes of ethics may help resolve concrete ethical dilemmas for trainees by defining the standards of physician conduct and describing the ethical aspirations of a professional field (6, 20, 42, 43). Knowledge of legal and institutional documents, such as hospital policy, may delimit or organize the options in caring for a patient (44, 45). Reading is an important, if underemphasized, part of a physician’s work (42, 43, 46). Its value becomes particularly evident when supervisors and residents must gather information about clinical ethical issues.

4. Explore possible ethical responses

Next, the supervisor and the resident should explore possible responses to the clinical and ethical issues at hand. For example, while it might arguably be “medically indicated” to use physical restraints or chemical sedation or both in treating a violent patient, these decisions have different ethical meanings in the care of a given patient in a particular setting. The ramifications of such clinical decisions are best understood through a timely, exploratory dialogue with a knowledgeable, trusted supervisor. In this step, the supervisor must anticipate the range of choices faced by the resident and have a sense of what alternatives are either permissible or unacceptable in the situation, based on clinical, ethical, legal, or other factors. Helping the resident to see the problems intrinsic to a “bad” choice may, in fact, be more important for the resident’s future practice than is helping the resident to see the advantages of a “good” choice in this step.

5. Provide guidance and support

The supervisor then provides guidance and support as the resident undertakes a course of action. As in the second step of identifying ethical dilemmas, the resident’s conflicting emotions often surface at this stage. Supervision affords an appropriate and well-defined opportunity to address the emotionally charged aspect of patient care when a tough decision must be made. While supervisors seldom should dictate resident’s choices, faculty expressions of direction and encouragement are important to the resident’s confidence at such moments. On occasion, for institutional, political, legal, or personal reasons, it may be necessary for supervisors to intervene in patient care dilemmas so that residents are adequately supported. In this step, supervisors thus can ensure that sound clinical approaches are implemented by residents who have not had to make problematic decisions alone. This approach affirms the primary role of the resident in making treatment decisions without ignoring the reality of the supervisor’s ultimate responsibility for patient care (19, 44).

6. Create a context for reflection

Finally, the supervisor should create a context for ongoing ethical reflection and clinical case review. In this step, the supervisor and resident should consider the clinical ethical decisions made in the care of individual patients with the benefit of hindsight. Supervisors may choose to discuss how they have responded to similar ethical dilemmas in their own training and practice, commenting on their successes as well as their occasional mistakes. By demonstrating their own decisional processes, revisiting past patient cases, and offering themselves as role models, supervisors may truly mentor their residents.

Case illustrations

This approach to clinical ethics teaching is a natural extension of traditional psychiatric resident supervision. It is not difficult to implement and may already occur implicitly in meetings between supervisors and residents when they focus on ethical issues. Making the process explicit and applying it to a variety of supervisory relationships occurring in residency, however, are crucial in the effort to develop a more systematic, clinically based approach to teaching ethics in psychiatry programs. The versatility and value of this supervisory strategy for teachers of psychiatry residents becomes apparent in illustrations of its use.

Case reports

Example One. A resident objected on ethical grounds to filling in federal forms that routinely declare certain psychiatric patients “decisionally incompetent.” In supervision, this issue was discussed in relation to a particular psychiatric inpatient whose decisional capacity did show some significant deficits. The resident had the impression that the patient’s financial benefits might be withheld if the form were not completed.

The first step in supervision was to clarify the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and related deficits in cognition and judgment. This served two aims: 1) to make certain that the patient’s clinical needs were not obscured in the resident’s passion to “do the right thing” by fighting institutional bureaucracy, and 2) to teach the resident about the phenomenology of the patient’s illness and about ways of assessing his decisional abilities, the basic educational goals of clinical supervision in this case. The second step was to help the resident to identify the ethical issues involved, such as the resident’s view of coercion by the institution, the resident’s perceived duty to protect a vulnerable patient whose financial benefits were apparently in jeopardy, the limited autonomy of the patient because of psychiatric illness, confidentiality, and others. The process of clarifying the ethical binds and personal frustrations experienced by the resident made it possible to approach the patient’s care with a better separation of the therapeutic goals from the complexities of training within a certain institutional setting. The supervisor talked with the resident about the distinction between decisional capacity, a clinical assessment, and competence, a legal determination. The resident was encouraged to read about decisional capacity and neuropsychological testing and to gather more complete historical information about the patient. She also sought information from faculty and administrators at the institution about the actual use of the federal form.

Possible responses to the ethical dilemma, that is, whether and how to fill out the form, were then explored by the resident and supervisor. With support and further discussion with the attending supervisor and permission from the patient and his family, the resident made a decision to write a separate report documenting the observed strengths and deficits of the patient. The patient’s benefits were not hindered. The resident worked further to change the policy requiring routine completion of the form. The resident and supervisor followed the patient case afterward and discussed the impact, both positive (special attention to clinical issues, continuation of the patient’s benefits, and a modest sense of accomplishment for the resident) and negative (additional work and some disruption of routine), of the resident’s choices in later supervision sessions.

Example Two. A resident on the consultation-liaison service worried about a discharge request made by a woman who had taken an impulsive overdose of antidepressant pills during an argument with her boyfriend. She had very nearly died and was in the intensive care unit on the medicine service. The patient was the mother of two children and homeless. Of greatest concern to the resident was that the patient’s boyfriend frequently and severely beat her. Although the patient asked to leave the hospital and denied suicidality, the resident felt that it was “unethical” to let the patient go.

The first step in supervision was to evaluate the clinical situation of the patient. She exhibited QRS widening on ECG and had elevated blood levels of a tricyclic antidepressant. On mental status examination, she was cooperative, sleepy, distractible, inaccurate by 4 days on the date, and unable to add or subtract even small numbers. It was clear that the patient’s medical indications warranted continued hospitalization. A discussion of the ethical issues encompassed topics such as patient autonomy and preferences, decisional capacity and standards of competence, informed refusal of treatment, quality-of-life factors, the duty to report child abuse, and others. It became evident that the resident needed additional information on the children (who, as it turned out, had previously been placed with the patient’s father) and on delirium, antidepressant toxicity, physical abuse, resources for battered spouses, and legal and institutional guidelines on holding patients involuntarily and on reporting domestic violence.

The resident and supervisor discussed a number of possible responses to the patient’s discharge request, including, if necessary, coerced observation and treatment. An evaluation was done by the supervising attending physician who clarified that the patient was not demanding to leave the hospital immediately. The patient stated, in fact, that she wanted treatment so that she would “be ok” before returning to “the shelter.” The patient agreed to remain in the hospital until she felt “a little bit better” and to accept the social work consultation. After careful assessment, the attending physician determined that the patient was capable of this level of consent in the acute situation. With the agreement of the attending supervisor, the resident decided to speak with the patient about remaining in the hospital and meeting with a social worker to help with her social situation. Over the next several hours, as the patient’s cardiac toxicity and delirium cleared, she decided to return to her boyfriend. Psychiatric and social work follow-up was arranged. When the resident and supervisor reviewed the case, the resident was still concerned about the patient’s refusal of inpatient psychiatric care and her decision to return to a reportedly abusive relationship. He could, however, articulate the limits of the law, the rights of patients, standards of competence necessitated by different clinical situations, and his own thoughts about each of these issues. He believed that he had handled the case well despite its unsettling facts.

Example Three. A resident miscopied an evening insulin dose when writing the orders on an elderly patient being admitted to the psychiatric unit. She discovered the error the next day when she found that the patient’s blood sugar readings were in the low 100s rather than the usual low 200s. The patient felt “fine,” and the orders were corrected. She wondered how much to tell the patient and his family about the mistake in prescribing insulin.

In the first step, the patient’s clinical status was investigated, and the issue was discussed with members of the treatment team who then were especially vigilant in their observation of the patient. The patient was considered to be stable and unharmed by the incident. The supervisor and resident discussed the ethical issues that surround medical mistakes, such as respect for persons, truth-telling, beneficence, justice, and the role of clinical outcomes in ethical analysis. They further talked about the resident’s discomfort with the mistake. The supervisor and resident explicitly acknowledged that the resident had not made such errors before, directly addressing the resident’s embarrassment. They then gathered information and read about the ethical issues surrounding medical mistakes and truth-telling and about the management of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The institution’s process for documenting mistakes, even for those with no clear harm inflicted, was also investigated and completed.

The choices before the resident (e.g., speaking with the patient and his family, or not, and talking further with the team members) were explored. The resident wished to talk about the error with the patient and treatment team immediately and with the family during their next scheduled session. The supervisor offered support to the resident as she pursued this series of discussions. Afterward, the supervisor reviewed with the resident the patient’s reaction (unconcerned), the family’s comments (critical), the teacher’s response (supportive), and the resident’s self-assessment (shaken but intact) and efforts to repair the situation (more than adequate). The supervisor and resident discussed this experience in the context of the resident’s personal and professional development as a psychiatrist.

Example Four. A psychiatric resident was told “confidentially” by a patient that he had sexually molested and physically hurt several girls though he had never been caught. The patient said that he now had his “eye on” a girl in his apartment complex. He offered no name, though he described her, and then would neither affirm nor deny any definite intention to abuse her. The patient had been admitted to the psychiatric unit to “rule out depression” after taking an overdose shortly after his wife left him.

The first step in supervision was to clarify the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and to take measures ensuring the safety of the patient and of others on the locked ward. The supervisor and resident performed separate evaluations on this patient as a matter of ward routine. They both found that the patient had had a long history of self-destructive and difficult behaviors but had no prior psychiatric admissions. He had consistently been diagnosed with character pathology and experienced no psychotic or uniquely depressive symptomatology. He understood that sexual abuse of children was “damaging” and “wrong.” He clearly stated what the consequences would be if he were caught. The patient was observed closely and behaved in a safe manner on the ward.

The next step in supervision involved discussing a number of ethical issues, including physician-patient boundaries and “secrets”; physician duty-to-warn, patient privilege, and confidentiality; culpability for deliberate, harmful actions by nonpsychotic psychiatric patients; dilemmas posed by “difficult patients”; and others. The supervisor and resident next sought expertise from the hospital’s attorneys, reviewed psychiatric and medical codes of ethics, and learned more about the patient’s past history. With direction from the institution’s legal counsel, the supervisor intervened and advised the police about the patient’s vague threat to sexually abuse an unnamed, but identifiable, girl. Her family was then notified of the threat to the child. The supervisor and resident together informed the patient of this action. The supervisor and resident discussed therapeutic options for this difficult patient and considered possible responses to the many ethical dilemmas his care presented. Ultimately, the patient was discharged and referred for treatment of pedophilia. He was informed that he was regarded as accountable for his actions and the fact that he had undergone a psychiatric hospitalization did not relieve him of responsibility for his behavior toward others. In this case, the resident appreciated the collaborative approach taken by the attending supervisor and felt that he had learned in the process of the patient’s care. The series of decisions in this extraordinarily challenging case were reviewed by the supervisor, resident, treatment team, and the legal counsel of the hospital, allowing for some sense of resolution if not satisfaction with the case. Additional follow-up information was not obtained, as the patient went to another state.

Each of these examples demonstrates how the everyday care of patients poses significant ethical challenges to psychiatry residents. Use of this six-step strategy is felt to have improved the quality of resident teaching and patient care in each case. Supervisors experience the approach as straightforward and as not extending the supervisor and resident significantly beyond the usual tasks of supervision in a way that is burdensome or contrived. The strategy thus offers an excellent method for use by supervisors in their efforts to foster residents’ decision-making skills and clinical judgment in ethically complex situations.

Conclusions

We have described why it is natural and essential to integrate ethics teaching into the individual supervision of psychiatry residents. A six-step approach to clinical ethics teaching in psychiatric supervision, with illustrations of its use, was presented. The approach builds upon the strengths and activities of supervisors, offers opportunities for self-education for both residents and supervisors, and uses the resident’s knowledge of ethics, ideally derived from a core didactic ethics curriculum during medical school and residency. The approach is presented as a method of promoting the development of sound clinical judgment in psychiatric trainees. Its ultimate aim is to improve the understanding and responses of psychiatry residents as they grapple with ethical issues that inevitably arise in the care of patients.

|

Table 1. Examples of Ethics Issues Encountered by Psychiatry Residents During Clinical Activities

|

Table 2. Elements and Relevant Issues Involved in Clinical Ethical Decision Making

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clarifying the clinical and ethical issues present in the patient’s care |

| Ensuring that specific clinical ethical decisions enacted are well-informed and reasonable, helping to prevent mistakes |

| Developing the knowledge and expertise of faculty and residents in clinical practice, medical science, and ethics |

| Demonstrating to trainees the importance of collaboration, curiosity, resourcefulness, and continuous learning in ethical decision making |

1 Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade W: Clinical Ethics: A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, Macmillan, 1993Google Scholar

2 McIlhenney TK, Pellegrino ED: The Humanities and Human Values in Medical Schools: A Ten-Year Overview. Washington DC, Society for Health and Human Values, 1982Google Scholar

3 Yager J: A survival guide for psychiatric residents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30:494–499Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Siegler M: Decision-making strategy for clinical ethical problems in medicine. Arch Intern Med 1982; 142:2178–2179Crossref, Google Scholar

5 American Medical Association: Special Requirements for Residency Training in Psychiatry. Chicago, IL, American Medical Association, Graduate Medical Education Directory 1993–1994, pp 121–126Google Scholar

6 American Psychiatric Association: The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

7 Bloch S: Teaching of psychiatric ethics. Br J Psychiatry 1980; 136:300–301Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Coverdale JH, Bayer T, Isbell P, et al: Are we teaching psychiatrists to be ethical? Academic Psychiatry 1992; 16:199–205Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Hafferty FW, Franks R: The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med 1994; 69:861–871Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Forrow L, Arnold RM, Frader J: Teaching clinical ethics in the residency years: preparing competent professionals. J Med Philos 1991; 16:93–112Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Kantor JE: Ethical issues in psychiatric research and training, in Review of Psychiatry, Vol 13. Edited by Oldham JM, Riba MB. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

12 Lane LW: Residency ethics training in the United States: special considerations and early experience, in Symposium 1990 Proceedings of the Westminster Institute for Ethics and Human Values: Medical Ethics for Medical Students. London, Ontario, Canada, 1990 pp 21–32Google Scholar

13 Lazarus JA (ed): Section 111, Ethics, in Review of Psychiatry, Vol 13. Edited by Oldham JM, Riba MB. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 319–459Google Scholar

14 Michels R: Training in psychiatric ethics, in Psychiatric Ethics. Edited by Bloch S, Chodoff P. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1981, pp 295–305Google Scholar

15 Miles SH, Lane LW, Bickel J, et al: Medical ethics education: coming of age. Acad Med 1989; 64:705–714Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Perkins HS: Teaching medical ethics during residency. Acad Med 1989; 64:262–266Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Roberts LW, McCarty T, Lyketsos C, et al: What and how psychiatry residents at ten programs wish to learn about ethics. Academic Psychiatry 1996; 20:131–143Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Sider RC, Clements C: Psychiatry’s contribution to medical ethics education. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:498–501Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Stone AA: Ethical and legal issues in psychotherapy supervision, in Clinical Perspectives on Psychotherapy Supervision. Edited by Greben SE, Ruskin R. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 11–40Google Scholar

20 Bernal Y, Del Rio V: Psychiatric ethics and confidentiality, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 4th ed. Edited by Kaplan HL, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1985Google Scholar

21 Lakin M: Coping with Ethical Dilemmas in Psychotherapy. New York, Pergamon, 1991Google Scholar

22 Hundert EM: A model for ethical problem solving in medicine, with practical applications. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:839–846Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Sadler JZ, HuIgus YF: Clinical problem solving and the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1315–1323Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Committee on Therapy, Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry: Psychotherapy in the Future (GAP Report No. 133). Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

25 Ende J: Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA 1983; 250:777–781Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Culver CM, Clouser KD, Gert B, et al: Basic curricular goals in medical ethics. N Engl J Med 1985; 312:253–256Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Pellegrino ED, Hart RJ, Henderson SR, et al: Relevance and utility of courses in medical ethics: a survey of physicians’ perceptions. JAMA 1985; 253:49–53Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Yager J: Psychiatric residency training and the changing economic scene. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1987; 38:1076–1081Google Scholar

29 Boyle PJ, Callahan D: Minds and hearts: priorities in mental health services. Report of the Hastings Center Project on Priorities in Mental Health Services. Hastings Cent Rep 1993; 23(suppl):S1–S24Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Barnard D: Residency ethics training: a critique of current trends. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:1836–1838Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Jacobson JA, Tolle SW, Stocking C, et al: Internal medicine residents’ preferences regarding medical ethics. Acad Med 1989; 64:777–781Crossref, Google Scholar

32 American Medical Association: Evaluation Survey Report on the Effectiveness of Medical Ethics Training. Washington DC, American Medical Association, Ethics Resource Center, 1985Google Scholar

33 Arnold RM, Forrow L: Assessing competence in clinical ethics: are we measuring the right behaviors? J Gen Intern Med 1993; 8:52–54Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Meisel A, Roth LH: What we do and do not know about informed consent. JAMA 1981; 246:2473–2477Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Stanley BH, Sieber JE, Melton GB: Empirical studies of ethical issues in research. Am Psychol 1987; 42:735–741Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Eichelman B, Wikler D, Hartwig A: Ethics and psychiatric research: problems and justification. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:400–405Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Stein SP: Supervision of the beginning psychiatric resident, in Clinical Perspectives on Psychotherapy Supervision. Edited by Greben SE, Ruskin R. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 73–84Google Scholar

38 Butterfield PS: The stress of residency: a review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 1985; 148:1428–1435Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Beauchamp TL, Childress JF: Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 4th ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994Google Scholar

40 Anzia DJ, LaPuma J: An annotated bibliography of psychiatric medical ethics. Academic Psychiatry 1991; 15:1–17Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Sacks MH, Sledge WH, Warren C: Core Readings in Psychiatry: An Annotated Guide to the Literature, 2nd ed. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

42 American Medical Association: Code of Medical Ethics: Current Opinions with Annotations, 1994 ed. Chicago, IL, American Medical Association, Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, 1994Google Scholar

43 Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Am Psychol 1992; 47:1597–1611Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Simon RI: Clinical Psychiatry and the Law, 2nd ed. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

45 Reid WH: Treatment of violent patients: concerns for the psychiatrist, in Review of Psychiatry, Vol 8. Edited by Tasman A, Hales RE, Frances AJ. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1989Google Scholar

46 Tiberius RG, Cleave-Hogg D: A database for curriculum design in medical ethics. Journal of Medical Education 1984; 59:512–513Google Scholar