A Model for Ethical Problem Solving in Medicine, With Practical Applications

Abstract

Despite the dramatic increase over recent years in the research and teaching of medical ethics, there exists no theoretical framework within which to conceptualize ethical problems in medicine, to say nothing of solutions to these problems. The model proposed here attempts to fill this void by developing a conceptual understanding of the nature of moral dilemmas that can be applied to both theoretical and practical problems in medicine. Practical applications are demonstrated in three areas: personal ethical problem solving, hospital ethics committees, and the teaching of medical ethics. Suggestions are offered for the extension of these and other applications of the model, a model proposed as a foundation to be built upon through further research and daily experiences in a world of conflicting values.

A difficult problem becomes a “dilemma” when we are quite sure that we will be making a big mistake regardless of whatever path we choose. It is instructive to consider moral dilemmas in this context. The anxiety we experience as we face each unpalatable alternative informs us about the nature of moral dilemmas. It seems that any decision we make will violate one or another value which we hold dear. Unfortunately, the many values that bear on any given dilemma are what philosophers call “incommensurable.” That is, it is impossible to quantify just how much one value (say, social welfare or telling the truth) is “worth” in terms of another value (say, individual liberty or relief from suffering). Yet, as we choose among possible actions, we are often forced to balance one incommensurable value against another, to balance a patient’s individual liberty against social welfare, to balance our standards of truth-telling against the relief of suffering.

Perhaps the only scale we have to carry out such a balancing act is the anxiety that our conscience dutifully provides in the process. By striving to find the path that makes us least anxious, we presumably balance a host of incommensurable values according to the scale of our conscience: our anxiety increases as we contemplate trading off too much liberty in the name of social welfare or too much of the truth in the name of relieving suffering. This still leaves us feeling as if we have made a big mistake (since we have compromised values that we hold dear), but at least it is a good strategy for “cutting losses.” We typically go through this process unconsciously, and it is quite difficult to articulate the pattern of balancing of values that we have achieved. It is, in fact, difficult just to list all of the relevant values that stand in need of balancing.

If we could articulate the various patterns of balanced values offered by our conscience, what we would have in their raw form are what we commonly refer to as our “moral principles.” While we do not usually think of them in this way, our moral principles are the “equations” we claim to use when forced to measure incommensurable values against one another.

Moral principles versus moral actions: a place for consistency

The “balancing equations” that are our moral principles are generally much more complicated than the moral actions that we take as a result of the balancing—the unplugging of a respirator, the abortion, the psychiatric commitment. This distinction is important because doctors are typically concerned with where consistency fits into all of this—and it is no small matter that the demand for consistency applies at the level of principles, not actions.

This point is illustrated by the following true case of an obstetrician-gynecologist whose confusion about this issue led her to perform an abortion that she herself thought unethical. The doctor had always been a strong supporter of the abortion rights movement, and she firmly believed in “abortion on request” as a general principle. But in the case in question, an abortion had been requested only because modern technology, in ruling out various congenital abnormalities, had also determined that the fetus was female, and the mother decided she would rather have a boy. The doctor’s own “instincts” (e.g., conscience) told her that this was not a good reason for an abortion. But, because she had always agreed to perform requested abortions in the past, she felt that “to be consistent,” she would have to agree to do this one. She could not, however, seem to get the case out of her mind.

After further reflection, the doctor realized for the first time that her personal moral principle on abortion was much more complicated than could possibly be embodied in a universal action rule like “abortion on request.” The case forced her to consider all of the values she held dear (autonomy of the mother, health and welfare of the mother and baby, social welfare, and so forth) that weighed on both sides of the abortion question. She then realized that she held the mother’s autonomy and health as a preeminent value but not the only value—that in our modern world with its multiplicity of goods, ends, and values, no single value can have infinite and universally overriding weight. Her actual moral principle concerning abortion did indeed assign very great, but not infinite, weight to the mother’s autonomy. The case was problematic for her because it was one in which that particular value was outweighed by others in the “balancing equation” that represented her moral principle. Only later did she come to understand that the demand for consistency applies at the level of principles, not actions. This was indeed one case where, to be consistent, she would not want to do an abortion when it was requested.

This case illustrates only the first step in this doctor’s struggle to bring her articulated “moral principles” into harmony with her actual moral experience (i.e., the feelings engendered by her conscience as she considers each possible moral action). She is now armed with a new moral principle to guide her decision making, and her moral experience will be different, for having worked through this case, when she faces her next moral dilemma. Thus our moral experience and our moral principles are kept in an ever-evolving equilibrium as throughout our careers we have new moral experiences and reflect on our working moral principles. Early in this process it is easy to fall into the trap of believing that moral principles take a simple, universal form with the addition of a small number of exceptions, such as “abortion on request except for sex selection” or “tell the whole truth unless the patient specifically requests otherwise.” But with more experience the exceptions build, and the addenda “unless the patient requests otherwise, or unless a life will be endangered, or unless . . .” become recognized as the balancing of a set of values that come into play in diverse and seemingly unrelated ethical problems.

A model for ethical problem solving

The earlier conceptualization of how our moral principles and moral experience evolve has the advantage of reflecting our actual experience with the process. In teaching medical ethics to first- and second-year medical students over several years, I have been struck by the simplicity of medical students’ early articulations of their principles (“never lie to a patient,” “always do everything to save your patient’s life”) and by the evolution of their more mature principles as they struggle with the classic problem cases. When I was a second-year medical student, I once wrote an article defending the position of always telling patients the whole truth—a true testimony to the process I am now describing. (That article was, mercifully, rejected for publication.) Once I was in the clinical setting, it did not take long for my conscience to inform me of the problems with my simple principle, although my other early formulations still went something like: “tell the whole truth unless it will result in X, Y, or Z,” as each successive problem case gave rise to another “exception.” It was only later that I realized how many of these exceptions were the manifestations of other values competing with the value of truth-telling in my own value-balancing process. At that point it became possible to see how the megaequation of all the relevant basic values and their relative weights can become a practical tool for keeping moral experience and principles in their dynamic equilibrium: each new dilemma exposes a novel division of values conflicting around the facts of a case and thus sharpens our own weighting system as we reflect on the problems associated with each alternative action.

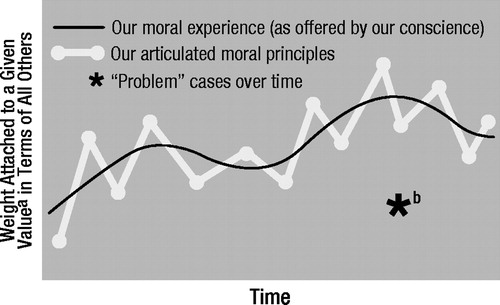

This is a variation of John Rawls’s notion (1) of a “reflective equilibrium.” As shown in figure 1, each new moral dilemma we face helps us clarify our moral principles as we reflect on the conflict between basic incommensurable values weighing on each side of a case. Armed with our new understanding of the principles on which we plan to base our future decisions, we find that our moral experience is also different when we face the next problem case. Obviously, these problem cases or dilemmas are more than simply nasty situations: they also present a new opportunity to learn about our principles and realign them with our moral experience. (It is often difficult to appreciate this opportunity in the heat of the moment, and it is usually in later reflection that equilibrium is restored—hence a “reflective” equilibrium!)

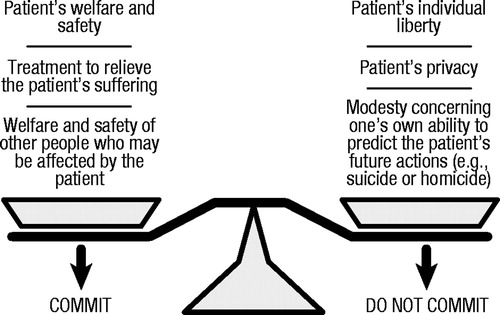

A good way to carry out this process is by actually writing lists of the conflicting values in each case. An example of a basic list for the ethical problem of psychiatric commitment is shown in figure 2. This is typical of an initial list one might devise when approaching a commitment case for the first time. With added experience, many more values are identified as weighing on each side of the scale. The best vehicle for developing one’s own moral understanding comes from saving these lists and watching how they develop over time. By observing the evolution of these lists of values in conflict, it becomes possible to watch one’s own “figure 1” develop around a given ethical dilemma.

What is meant by “medical ethics”?

By following the evolution of lists of values such as those described earlier, it also becomes possible to understand how the expression “medical ethics” can have real meaning. At first, this common expression may not appear to be at risk for lacking substantive meaning, but the weight of hundreds of years of moral philosophy is against it. If Immanuel Kant (2) left any legacy of thought at all, it is our modern notion that “moral rules” must by definition apply to every person equally. For the past decade, Americans have been quick to remember this when a suggestion is made that “Presidential ethics” can refer to something other than the ethics that apply to all of the rest of us. Thus, the notion of a separate field of “Congressmen’s ethics” would immediately raise the question of meaning in a way that medical ethics seem not to do.

One simplistic solution is that, since doctors are engaged in making certain types of decisions that others are not, medical ethics refers to the field of ethical issues that tend to be faced by doctors because of the work they do. This conceptualization is coherent, but it lacks depth, especially as increasing numbers of nonmedical professionals find themselves entwined in these same ethical issues. A second simplistic solution would be to try to abolish the expression “medical ethics,” reminding people of the dangers that lurk if doctors (or politicians) start to think that they have a different code of ethics from everyone else just because of their role in society. This solution is neither practical nor desirable, given that there is a third and useful way to conceptualize the problem of medical ethics.

The third solution focuses on the pattern that develops as doctors struggle with lists of values and their relative weights around the many ethical problems they face each day. By studying such lists across diverse moral dilemmas, it becomes possible to uncover a pattern of value balancing that is characteristic of medicine as an institution and that distinguishes medicine from other professions. Dedicated as it is to the relief and prevention of suffering, medicine is anything but value-neutral from the start. It is therefore not surprising that medicine gives relatively more weight to considerations of welfare than to considerations of justice as compared to the legal profession, for example. In law, the crucial factor in what to do now is often that of justice, which forces lawyers to painstakingly assess how people got into their current predicament. In medicine, the backward-looking issues of justice and guilt weigh less heavily than in law. In allocating resources to two patients with liver disease, doctors consider the patients’ welfare (i.e., the consequences for the patients’ health) much more than they consider whether or not one patient is more to blame for his or her condition (for example, when one case was caused by excessive ingestion of alcohol, while the other came from inadvertently eating the wrong clam). Medicine as a profession thus manifests a certain pattern of value balancing that distinguishes it from the legal profession. The suggestion here is that the pattern of value balancing that is characteristic of medicine (e.g., assigning relatively less weight to justice than to welfare as compared to the legal profession) is what gives meaning to the expression “medical ethics,” which refers to this medical pattern.

How this pattern came to be and how it is perpetuated are no small matters. Obviously, a two-way street exists, wherein young people choose medicine as a profession because they have been raised with and already hold this pattern of values while, at the same time, the established profession, through medical education, teaches this pattern to medical students and house staff, who become “socialized” into the profession, or “professionalized” (to friends of the process). Given these strong forces at work, it is not surprising that attempts to force radical changes on the values of medicine are likely to fail. Those who would like to use insurance ploys to force doctors to treat differently those two patients with liver disease underestimate the power of medical ethics. Some insurers may wish to charge higher premiums to smokers or obese people, but they should not be surprised if doctors refuse to give less care to smokers than to nonsmokers when treating their cancers.

Added levels of complexity

Before we move to applications of the model described earlier, a number of added levels of complexity should at least be mentioned. For example, a distinction is often made in moral philosophy between what J.L. Mackie (3) has called “morality in the broad sense” and “morality in the narrow sense.” Morality in the broad sense refers to the search for general action-guiding principles. As we consider the moral thing to do (in the broad sense), we might weigh aesthetic considerations, the demands of etiquette, our own selfish wishes, and so forth. In addition to these, we would also weigh what is often called the issue of “morality,” taken now in the narrow sense. Morality in this narrow sense refers to only those considerations which are founded on basic values and which seem to operate through our consciences to counteract some natural tendency we might otherwise have to be selfish (4). It thus makes sense to say “I know morality dictates X, but there are other considerations here,” only when speaking of morality in the narrow, not the broad, sense. Both of these senses of morality are commonly used (and often confused), and we all too often achieve some understanding of one only to apply that understanding inappropriately to the other.

What I have written earlier applies to morality in the narrow sense. It is possible to use the same framework to model medical morality in the broad sense, but it is much more complex. In addition to the basic value-balancing act we face with a given moral dilemma, we are also operating within a web of institutions (our culture, state and federal law, a hospital), each of which has a somewhat different characteristic pattern of balancing values. It is the conflict among these different patterns that gives rise to the deepest of conflicts of interest in medicine. Thus, in the commitment example in figure 2, it may be fine to decide that a patient’s individual liberty outweighs his or her need for treatment in a given case, but if the patient is mentally ill and at all homicidal, the law requires that he or she be committed. (The law assigns relatively more weight than does medicine to the consideration of individuals other than the one in question.) Similarly, the current debate over for-profit hospital corporations focuses on the effects that must inevitably result when doctors choose to operate within yet another institution with yet another pattern of value balancing which differs from that of the institution of medicine (5).

Examples in which doctors are forced to act as “double agents” (as when psychiatrists [6] are called on by society to protect society from dangerous mentally ill people and not just serve their patients) highlight the difference between morality in the narrow and the broad senses, but these added levels of complexity are always operating, since decisions are always being made within a web of institutions. It would be possible to add “obedience to the law” to the values in figure 2, but it would have to be placed on both sides of the scale, since it might weigh in either direction depending on the facts of the case.

In fact, legal considerations are not the only ones to weigh on both sides of the scale, and this represents another added level of complexity. It is not uncommon for a value, such as personal autonomy, to weigh on both sides of a case—especially when this value arises with regard to two different individuals. But the same value may appear on both sides of the scale even with regard to the same person, as when there are quality of life issues weighing on both sides of a case concerning artificial life support. In these cases, it becomes useful to examine how these values come to appear on both sides and in what context they do so. As will be seen later, it is the working through of such problems that usually makes the best decision clear.

Finally, as one more added level of complexity, it is worth noting that if medical ethics is meaningful as a characteristic pattern of balancing values, this may differ from the pattern that represents the personal moral principles of an individual physician. It is one thing to observe the “two-way street” of medicine inculcating medical values in young doctors and young people choosing medicine because they hold those values already, but it is another to pretend that personal codes of ethics on the part of even the most well-intentioned physicians will always coincide with those of the profession as an institution. This is particularly a problem for young doctors who have not yet had enough experience to internalize many of the values of the profession. When such conflicts arise in medical students and house staff between, as one fourth-year medical student once put it, “what I feel I should do as a doctor and what I feel I should do as a person,” it is important not to underestimate the power of that experience in the process of professionalization. Within medicine’s characteristic pattern of balancing values, there is great scope for differences of opinion between intelligent and “ethical” doctors. This is indeed what makes medical ethics such an important (and lively) field for discussion and research.

Applications to personal ethical problem solving

When we apply the model of ethical problem solving to the ethical dilemmas we face daily as physicians, the most striking quality that stands out is just how personal the process is. It is not surprising that once physicians start writing out their lists of competing values over time, they keep those lists under lock and key. The personal nature of our moral principles is hardly surprising, since these principles reveal parts of us that we often hide from ourselves, let alone from friends or colleagues. (Even in the confidence of psychoanalysis, it is often only through analyzing our resistance to facing such matters that the analyst comes to understand them!)

This emotional side of what might otherwise be considered a rigorous intellectual procedure for solving ethical problems should warn against a dangerous trap—that of using the procedure to lie to ourselves. Consider, for example, the case of a terminally ill patient in great pain from the bony metastases of her cancer, who seems unable to be weaned from her respirator. We set out to use our conscience to balance the values involved by anticipating the anxiety we feel as we contemplate our various alternatives. But maybe what we are really doing as we choose to “pull the plug” is not carrying on our reflective equilibrium at all: perhaps it is merely processing the anxiety we are feeling because our own mother or grandmother is (or was) in a similar situation in which we felt powerless to change things. This is the factor that might be called “countertransference distortion” (by analogy with the distortion arising from the analyst’s own unconscious issues in a psychoanalysis). It is a factor that is difficult to separate from the process described earlier, but one that must be considered in every case. Our personal experiences outside our professional lives must and should influence our moral experiences within our professional lives. We must, however, be on guard for “outlying points on the curve,” like the asterisk in figure 1. Notice that, as drawn, the asterisk would have been less of an outlier earlier in time, however. Indeed, it is only by having a fairly good idea of where our equilibrium is and has been (i.e., by being the “well-analyzed analysts of our dilemmas”) that we can prevent ourselves from letting such personal issues interfere with our professional moral integrity—one of the most difficult challenges of all.

When we have made the effort to work through this difficult balancing act, the personal rewards are equally great. We can, for one thing, defend our decisions against the criticism of others, as well as against our own self-doubt. A doctor may be criticized (or criticize himself or herself) for having failed to give enough weight to a patient’s individual liberty when the patient is committed into a hospital, for example. The accusation is made: “Well, I guess that person’s individual liberty did not mean much to you” (or “to me” in the case of self-doubts). Having worked through the difficult balancing of values, however, we know that the patient’s liberty meant quite a bit to us—it was, in fact, the value we attached to the patient’s liberty that made the decision so difficult. Once such trade-offs are understood within the context of the model, then, it is of the utmost importance to remember that the values which are outweighed in a given case were far from “nothing” to us. The pains we take in making decisions in the face of dilemmas testify to the priority that we did indeed attach to those values which were ultimately outweighed. It is in this way that we can understand what is meant when we say that we give honor to life not by always preserving life at any cost but by the pains we take when we make decisions that have the opposite effect.

Applications to hospital ethics committees

Many institutions, particularly hospitals, have recently developed standing ethics committees that serve functions varying from support group, to educator, to tribunal. Some of these committees merely form a forum for discussion, while others hand down actual (binding or nonbinding) recommendations for action (7). Since many of the most difficult ethical problems within an institution are now addressed by a committee, it is worth mentioning how the model described earlier might be used (or abused) in such a setting.

Each member of an ethics committee brings to it a great variety of experience with balancing values one against another in a great variety of contexts and within a great variety of institutions. A certain amount of self-selection usually occurs, and members of the committee typically have relatively strong, well-articulated moral principles. They may not put it in these words, but they each know pretty well how much safety they are willing to trade off for how much privacy, how much welfare for how much justice. The ethics committee itself, however, forms a new and unique institution that tends to polarize its members: the member who gives the most weight to justice considerations (relative to other values)—even if only marginally so—will quickly become the group’s “defender of justice” (this member will often be a lawyer if there is one on the committee, for reasons discussed earlier). As case after case is addressed by the committee, members soon come almost to expect the “defender of privacy,” the “defender of social welfare,” and the “defender of patient autonomy” each to take his or her ground. Indeed, the knowledge that the defenders of patient autonomy and privacy are at the committee meeting makes it easier for the defender of social welfare, for example, to argue for the involuntary commitment of an arguably dangerous mentally ill patient. After all, the balancing of many other values against social welfare no longer has to be carried out in the mind of any given member; it instead gets carried out among members, each of whom argues for the weight of one or two values only.

The group dynamic I am now describing is, of course, one of the most basic of group behaviors. A form of group projective identification, it is the process by which conflicts really occurring in the mind of each group member get played out within the group, as each member accepts and “holds for the group” one part of the story. In observing this process as a member of a medical-school-affiliated community hospital ethics committee, I have been impressed by how vividly the committee as a group can demonstrate the model that I have proposed for individual ethical problem solving. This is not merely an interesting group dynamic; it has important practical correlates as well. Ethics committees are often charged with making policy recommendations to the hospital’s governing body (or actually setting policy in some cases, either through precedent or more formally). In choosing among a wide spectrum of policy options, an ethics committee can use to great advantage the process by which competing values become represented by different members, as the following example will demonstrate.

Our ethics committee was asked to consider the case of a nurse who had accidentally stuck her finger with a needle that had been used to draw blood from a homosexual patient suffering from pneumocystis pneumonia. The patient had a presumptive diagnosis of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), although he refused laboratory testing for both T-cell subset ratios and human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type III (HTLV-III) antibody titers. He stated that he had no desire to know the results of such tests himself and feared that the information would be used against him, if not in the hospital, then by potential employers who might ask about such tests should he, at least temporarily, be back in the job market. The nurse said she wanted to know the patient’s HTLV-III immune status, even though she claimed to know all the data on needle stick “exposures” to AIDS and problems with HTLV-III antibody testing. She said she realized it was not like a needle stick exposure to hepatitis, in which the hepatitis immune status of the patient might lead to prophylaxis for the nurse, since her behavior in this case would be unaffected by the result of the test. (She stated that she planned to have her own HTLV-III antibody titer checked every 6 months.) She did, however, believe that she had a right to the information, and she based her claim partly on her having sustained the needle stick in the course of caring for the patient.

A deadlock ensued when the patient repeatedly refused to give consent for the tests, and the case was brought before the ethics committee. As the committee members took up their “established positions” (the “defender of privacy” speaking for the patient’s fears of discrimination, and so forth), a number of constructive new policy options were articulated as the members sought specific ways of preserving the values that seemed to conflict. If the patient’s decision to refuse the test was really based only on his fear that the information would get into the wrong hands (or even if he himself also wanted not to know), perhaps the pathology department could devise a triple-blind coding system so that only the patient and nurse (or even only the nurse) could ever find out the result. The value of privacy could then be upheld without having to trade off anything else. If the patient still refused, his autonomy stood in direct conflict with the nurse’s wishes, and privacy was not the issue. Other supports could then be put in place for the nurse, including further education about such tests and their meaning, to give what reassurance she sought without having to compromise the patient’s right to refuse the tests (which the committee felt must outweigh the nurse’s desire to know the result). And so what was in the beginning a question of “should we do the test or not” turned into a discussion of the numerous actions that might maximize all of the values that seemed to conflict, before any trade-offs must, in the end, be made.

The policies developed by an ethics committee are the analogue of an individual’s moral principles. The policies define the “balancing equations” that calculate how much of one value is to be traded off for others when such trade-offs must be made. We see in the development of such policies the same equilibrium discussed earlier: people’s moral experiences, offered by their consciences, affect the policies developed; but the policies, once photocopied and hung around the hospital, will also affect people’s moral experiences when the next problem case arises. Since their policies affect the moral experience of the entire hospital community, ethics committees must take extra care in deciding when, how, and whether or not to establish any given policy. Even a well-written and thoughtful policy, if poorly timed, can disrupt the moral environment of an institution strained by values in conflict. (It is easier to discuss how the professions of medicine and law might differ in their characteristic pattern of balancing values than to note the obvious fact that nursing, social work, hospital administration, and other related professions each also have their own pattern of balancing values which differs from that of medicine—a fact that we often find embarrassing and try to ignore.)

The main point here, however, is that an ethics committee can use the process by which it balances values among members to create new policies that alleviate the need for trading off one value for another, and the same outcome can and should be achieved by individuals balancing values within their own conscience. Once the values in conflict are understood, the original dilemma—stated as an unpalatable choice between “tell the whole truth or lie” or “commit the patient or just let him go”—may dissolve through the many options that might preserve the truth and relieve suffering, respect the patient’s liberty and preserve social welfare. This, after all, is the most desirable outcome when we are faced with a dilemma: not to have to choose after all between the “big mistakes” in question.

Applications to teaching medical ethics

I shall conclude by discussing the proposed model with regard to the teaching of medical ethics in medical schools and residency training programs. I do not mean to discuss here the practical side of how a given group of students might apply the model to learn about various specific moral issues (which could be done in a variety of ways). What I would like to address is, in essence, the relationship between theory and practice.

The dynamic equilibrium represented in figure 1 is, in a way, an equilibrium between theory and practice, between one’s intellectual understanding of one’s moral position and one’s actual moral experience. It may well be that the curve will end up in the same place eventually whether the first step in the equilibrium comes from the theory or the practice side, but early on the difference may well be dramatic. If, for example, one’s first struggle to articulate personal principles about abortion occurs after, as a third-year medical student, one has assisted with a second-trimester abortion, the practical, experience side will likely set the equilibrium in a definite direction. (This is why the antiabortion movement uses grotesque photographs to “educate” people to consider the pros and cons of abortion.) If, instead of the practice side, the theory side started off the process—if as first- or second-year students the individuals in question were forced to balance the values involved for themselves—their moral experience in the operating room would likely be somewhat different, and the equilibrium would be set in motion initially in a somewhat different direction.

The relationship between theory and practice, and which comes first in medical training, is thus no small matter. Of course, theory cannot exist in complete isolation from practice, and so cases must be used to focus the theory even in preclinical ethics courses. But this effort pays off when the students, in their clinical training, come to new moral experiences with more mature moral principles. In medical training we do not wait until people’s lives are at stake to teach anatomy and physiology. Neither should we wait until moral choices must be made to teach medical ethics. Ethics must be taught alongside every clinical decision, but solid foundations must be laid for moral as well as clinical decision making.

For the past 5 years I have been teaching medical ethics to first- and second-year medical students at Harvard Medical School. My belief that the equilibrium should start with theory goes beyond the preclinical stage of training of the students in the classroom. The course itself begins by introducing the values themselves—what is meant by welfare, justice, liberty, and so forth. If these concepts become the tools that are used to dissect ethical problems, surely they should be analyzed before their meaning might be prejudiced by weighing one against the next in a medical context. Indeed, to resist the effects of the class’s prejudices, the values in question are introduced through a historical review of their development and of the various moral theories through the ages that emphasized the primacy of each. Only then are the classically problematic moral issues in medicine addressed, week by week, by students prepared to methodically balance the many values that conflict around each case.

This application to the teaching of medical ethics thus enables each future doctor to sharpen his or her own moral position by using a rigorous problem solving method. By focusing each student’s attention on his or her own moral experience, the model I have described provides a tool for thinking about ethical problems—a tool that teaches how to think, not what to think. Teaching medical students what to think about ethical issues has no place in medical education in a free society—it is merely propagandizing of the worst kind. As a tool for conceptualizing ethical problem solving, the model I have discussed enables teachers to teach the proper subject of the medical ethics curriculum: how, not what to think.

Each of us can use the model to come to our own conclusions about how to act in any given case. By focusing our attention on the particular values in conflict, we sharpen our own moral position and evolve in the reflective equilibrium that exists between our moral principles and our moral experience. But the model does a bit more than that. It also provides a context within which we can carry out meaningful and productive moral argument. Just as I challenge my students to define their own pattern of how each value is to be weighed against all others, we must all continually challenge one another to do the same as the process of moral education continues through our lives. Only then can we understand how different points of view really conflict, and only then can we each preserve the vitality of our own morality.

Summary and conclusions

In this article I have introduced a model for ethical problem solving in medicine and discussed a few of its practical applications. It is a descriptive model in that it seeks to demonstrate certain basic principles by modeling the behavior we see around us every day. In particular, the model focuses on the conflicting values that give rise to the “dilemma” nature of ethical problems. Moral principles are conceptualized as the “equations” offered by our conscience that compute how much each value is “worth” in terms of each of the other conflicting values, and these principles are found to evolve in a dynamic “reflective equilibrium” with our moral experiences. The moral actions we take are determined by the ultimate balance of relative weights assigned to all of the competing values as they arise from the particular facts of a problematic case and so each new dilemma helps us develop our principles by introducing new patterns of conflicting values. The effort it takes to carry out such a balancing act in a problematic case reminds us that the outweighed values were not “nothing” to us in that process, and this itself can help avoid many misunderstandings and confusions.

The model dismisses the simple-minded position of those who define their moral principles in terms of adherence to a consistent action (always tell the whole truth, always preserve life at all costs) by emphasizing that consistency applies at the level of principles, not actions. If one’s principle incorporates a given trade-off among the preservation of life, individual autonomy, and relief from suffering, different cases are bound to result in different actions, but consistency is still found at the deeper and appropriate level. Medicine itself is not neutral with respect to trade-offs between values, and the pattern of value balancing characteristic of medicine as a profession gives rise to what is commonly called “medical ethics”—an ethics that may conflict with that of other institutions within which doctors must make moral decisions (and may at times conflict even with doctors’ personal codes of ethics, particularly at early stages of their training).

The practical application of the model to ethical problem solving reveals a number of advantages, not the least of which is the possibility of finding alternative solutions that avoid the “dilemma position” altogether. By considering the actual values that are in conflict, we may discover options that alleviate the need to trade one off against another—the best of all possible solutions when it can be achieved. Keeping track of our own reflective equilibrium thus not only prevents our stated moral principles from straying too far from our moral experiences, it presents a strategy for maximizing adherence to all of the values that we hold dear. It also enables us to defend our moral position against criticism, to identify where points of real conflict exist with others and thus make moral discourse more meaningful, and, crucially, it can enable us to see when personal (countertransference) issues are giving rise to feelings that lie far off the curve of our reflective equilibrium. Writing successive lists of values on pieces of paper over time may seem like a simple-minded exercise, but it is one of the only ways to avoid the dangerous trap of lying to ourselves about our own moral position when difficult personal issues confuse our rational approach to ethical problem solving.

My introduction of a few practical applications of the model (to hospital ethics committees, medical ethics teaching, and personal ethical problem solving) is intended only as a beginning. A great number of applications can be made. For example, cross-cultural ethical problems can be understood by recognizing that different lists of values are in conflict, rather than merely different weightings of the same lists (as is usually assumed but is true only in single-culture problems). Health policy issues might be analyzed in terms of the competition within the political arena of each relevant institution’s characteristic pattern of value balancing. And so on. My goal here has simply been to introduce a method of conceptualizing ethical problem solving in medicine. The examples are meant primarily to define the model better and show how it might be put to work. just as theory and practice sharpen one another in an evolving equilibrium within the model, so too will the model itself evolve as it is applied in different contexts by different people. This is how deeper understanding develops, both within the medical community and within each of us.

Figure 1. Change Over Time in Relative Weight We Attach to a Given Value as Reflected in Our Moral Experience and Articulated Moral Principles

Figure 2. Model of Conflicting Values in the Ethical Problem of Psychiatric Commitment

1 Rawls J: A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1971, pp 48–51Google Scholar

2 Kant I: Critique of Practical Reason (1788). Translated by Beck LW. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1949Google Scholar

3 Mackie JL: Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. Baltimore, Penguin Books, 1977, pp 106–107Google Scholar

4 Warnock GJ: The Object of Morality. London, Methuen, 1971Google Scholar

5 Reiman AS: The new medical-industrial complex. N Engl J Med 1980; 303:963–970Crossref, Google Scholar

6 O’Brien Steinfels M, Levine C (eds): In the Service of the State: The Psychiatrist as Double Agent. Hastings-on-Hudson, NY, Hastings Center, 1978Google Scholar

7 Fost N, Cranford RE: Hospital ethics committees. JAMA 1985; 253:2687–2692Crossref, Google Scholar