Performance in Practice: Clinical Tools to Improve the Care of Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

To facilitate continued clinical competence, the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology are implementing multifaceted Maintenance of Certification programs, which include requirements for self-assessments of practice. Because psychiatrists may want to gain experience with self-assessment, two sample performance-in-practice tools are presented that are based on recommendations of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the US Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. One of these sample tools provides a traditional chart review approach to assessing care (Appendix A); the other sample tool presents an approach that permits a real-time evaluation of practice (Appendix B). Both tools focus on treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among adults age 18 or older, and both can be used as a foundation for subsequent performance improvement initiatives with the aim of enhancing outcomes for patients with PTSD.

In current practice, psychiatrists, like other medical professionals, are expected to maintain their specialty expertise in the face of an ever-expanding evidence base. Because a number of studies have demonstrated a gap between recommended evidence-based best practices and actual clinical practice, a variety of strategies have been developed with the aim of improving the quality of clinical care (1–10). Proactive approaches to improving quality of care such as the use of clinical reminders (11–19) and audit and feedback of practice patterns to practitioners (12–14, 19–22) have resulted in some degree of care enhancement in contrast to the limited success in changing clinician behavior via traditional didactic approaches to education (e.g., CME conferences) (11–15, 23–26). It is also likely that a combination of quality improvement strategies will be essential in promoting substantial improvements in patient care and outcomes (13, 20, 21, 26–30).

As part of this effort to bridge the quality gap between evidence-based practices and actual clinical practice, the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology are implementing multifaceted Maintenance of Certification (MOC) programs that include requirements for self-assessments of practice through reviewing the care of at least five patients (31). As with the original impetus to create specialty board certification, the MOC programs are intended to enhance quality of patient care in addition to assessing and verifying the competence of medical practitioners over time (32, 33). Although the MOC phase-in schedule will not require completion of a Performance in Practice (PIP) unit until 2014 (31), individual psychiatrists may wish to begin assessing their own practice patterns before that time. To facilitate such self-assessment related to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this article will provide sample PIP tools that are based on recommendations of two major guidelines published in the United States: APA's Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (34) and the U.S. Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress (35), supplemented by the latest evidence in the most recent APA Guideline Watch (36). Other noteworthy practice guidelines for the treatment of PTSD include the Australian guidelines for the treatment of adults with acute stress disorder and PTSD (37) and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence management of PTSD in primary and secondary care (38).

The PIP tools described here have been developed to specifically address care of PTSD among adults age 18 years and older; screening, diagnosis, and treatment of PTSD among patients younger than 18 years of age is beyond the scope of this article. A similar set of self-assessment tools for the treatment of depression among adults was published earlier (39), guided by recommendations from the APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder (40).

Evidence-based practice guidelines and quality indicators (41, 42) provide an important foundation for assessing quality of treatment. For a number of reasons, however, the realities of routine clinical practice may temper the development and assessment of a clinically appropriate treatment plan for a specific patient. First, as described previously (39), evidence-based practice guidelines and quality indicators are often derived from data based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Because patients in efficacy trials and even those in effectiveness trials must meet stringent enrollment criteria, they often differ in important ways from patients seen in routine clinical practice (43). For example, patients in RCTs are less likely to be suicidal, have co-occurring psychiatric and medical conditions that may interfere with treatment, or be as severely ill as patients in routine clinical practice. Such differences may need to be taken into account when a physician is formulating the best treatment plan for an individual patient.

In addition, when quality indicators are used to compare individual physicians' practice patterns, differences in patient characteristics and illness severity between practices may lead to false conclusions about differences in quality of care. In such circumstances, case mix adjustment is important to address confounding and permit accurate comparison of quality indicator results (44, 45). Also, inadequate attention to factors such as case mix adjustments may lead to unintended consequences such as excluding more severely ill or less adherent patients from practices in an attempt to improve performance on specific quality indicators. Finally, for patients who have complex conditions or are receiving simultaneous treatments for multiple disorders, composite measures of overall treatment quality may yield more accurate appraisals than measurement of single quality indicators (46–48).

Although the above caveats need to be taken into consideration, use of retrospective quality indicators can be beneficial for individual physicians who wish to assess their own patterns of practice. If a physician's self-assessment identifies aspects of care that frequently differ from key quality indicators, further examination of practice patterns would be helpful. Through such self-assessment, the physician may determine that deviations from the quality indicators are justified, or he or she may acquire new knowledge and modify his or her practice to improve quality. It is this sort of self-assessment and performance improvement efforts that the MOC PIP program is designed to foster.

INDICATORS FOR THE EVIDENCE-BASED RECOGNITION AND TREATMENT OF PTSD

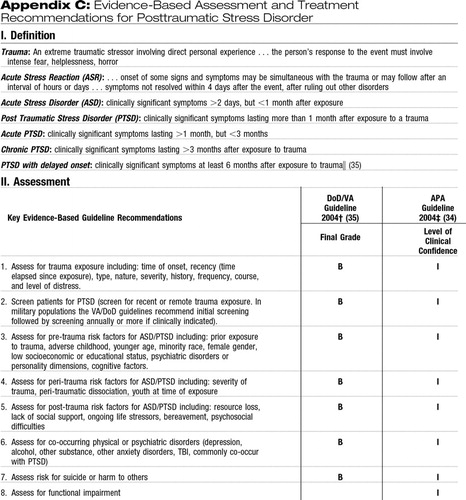

The evidence underlying the development of indicators for quality assessment/improvement is generally derived from three sources: 1) experimental studies (e.g., RCTs); 2) epidemiologic or observational studies; and 3) expert consensus. For ASD and PTSD, recent clinical practice guidelines have examined these sources of evidence and have been published in the United States by APA (APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder) (34) and the VA/DoD (Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress) (35). The clinical indicators in Appendixes A and B are largely derived from these guidelines supplemented with information from a recent Guideline Watch that updates APA practice guidelines (36) and focuses on recent evidence for pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment for PTSD. Appendix C highlights key assessment and treatment recommendations derived from the aforementioned guidelines (34–36)

INDICATORS FOR SCREENING, ASSESSMENT, AND EVALUATION OF PTSD

The need for screening and diagnosis of PTSD in psychiatric practice is underscored by the substantial prevalence of PTSD in both the general population and in high-risk populations, especially after exposure to specific traumatic events. For example, recent epidemiologic studies using DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria have found the lifetime prevalence of PTSD to range from 6.4% to 9.2% (49–51). In addition, women generally have a higher risk of PTSD than men, controlling for type of trauma (51). These findings support the importance of quality indicators focused on screening for PTSD in the general population using structured instruments such as the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C) (52). In recent studies of military service members deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, PTSD prevalence rates of 5.0%–19.9% have been found, varying based on strict or broad definition of PTSD using the PCL, deployment location, and pre-post deployment status (53). In addition, several reports have suggested that routine screening for PTSD can identify subsyndromal PTSD with significant disability at least as frequently as PTSD that meets the full diagnostic criteria (48, 54, 55).

In addition to routine screening for PTSD in general civilian and military populations, evidence has suggested the need for intensive screening and diagnostic efforts intended for populations with a history of exposure to trauma. For example, elevated rates of lifetime and current prevalence of PTSD have been reported for populations exposed to terrorist attacks [e.g., 12.6% PTSD prevalence among residents of lower Manhattan after the 9/11 attacks (56) and 31% PTSD prevalence among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing 1 year later (57)], natural disasters such as hurricanes [22.5% PTSD prevalence after Hurricane Katrina (58)] and earthquakes [24.2% PTSD prevalence 9 months after an earthquake in China (59)], and medically traumatic events such as burns [28.6% PTSD prevalence at 1 year (60)], cancer surgery [11.2%–16.3% 6-month PTSD prevalence after surgery (61)], acute coronary syndrome [12.2% PTSD prevalence at 1 year (62)], and hospitalization for traumatic injury [20.7% PTSD prevalence at 1 year (63)]. An additional consideration is the need for longitudinal screening of trauma survivors because the onset of PTSD symptoms may be delayed for 6 months or more in a substantial number of individuals. More specifically, a systematic review found that “studies consistently showed that delayed-onset PTSD in the absence of any prior symptoms was rare, whereas delayed onsets that represented exacerbations or reactivations of prior symptoms on average accounted for 38.2% and 15.3%, respectively, of military and civilian cases of PTSD” (64).

Finally, ongoing screening is essential in identifying PTSD in patients being evaluated or seeking treatment for other psychiatric conditions such as psychosis (65–67). Also, a substantial proportion of patients with mood and other anxiety disorders also have PTSD. For example, it has been estimated that 7%–40% of patients with bipolar disorder also meet the criteria for PTSD (68). In addition, the National Comorbidity Survey found the rate of affective disorders to be 4 times higher among respondents with PTSD than among those without PTSD (e.g., 47.9%–48.5% for major depressive episode in subjects with PTSD versus 11.7%–18.8% for those without PTSD) (49). Similarly, rates of anxiety disorders other than PTSD were twice as high or more among those with PTSD (e.g., 7.3%–31.4% for a variety of specific anxiety disorders) than among those without PTSD (e.g., 1.9%–14.5% for the same range of disorders) (68). Finally the same study reported alcohol abuse/dependence to be up to twice as high among those with PTSD (e.g., 51.9% for men and 27.9% for women) compared to individuals without PTSD (e.g., 34.4% for men and 13.5% for women) (49).

TREATMENT INDICATORS

Indicators for assessing the quality of treatment should ideally be derived from experimental treatment trials, preferably RCTs. However, in the absence of such trials, clinicians must rely on clinical experience augmented by data from observational and retrospective studies and expert consensus. Evidence-based practice guidelines provide clinicians with a valuable clinical resource by compiling and processing the most recent scientific knowledge and expert consensus for the treatment and management of selected disorders. Well-established practice guidelines such as those developed by APA and the VA/DoD, that have been referenced here, use a rigorous standardized process for searching the literature, data extraction, and synthesis (35, 69). For ease of use, recommendations are then graded based on the level of supporting evidence. For example, Appendix C includes the level of clinical confidence/grade for each of the recommendations based on the VA/DoD and APA practice guidelines, and the definition associated with each level/grade.

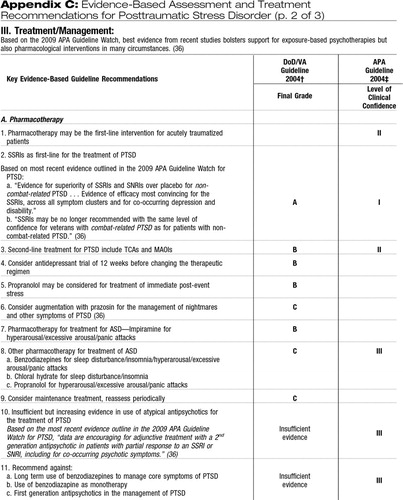

PHARMACOTHERAPY

The APA and VA/DoD guidelines uniformly recommend the initiation of serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (SSRIs) as first-line treatment for PTSD (34, 35). However, the recent Guideline Watch (36) and Institute of Medicine report (70), although still supporting use of SSRIs for PTSD among civilians, have found less RCT evidence to support these medications for the treatment of combat-related trauma. There is also less RCT evidence supporting the use of other antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and non-SSRI second-generation antidepressants) (36). Expert consensus plus observational studies suggest consideration of an antidepressant trial of at least 12 weeks at adequate doses before the therapeutic regimen is changed and consideration of long-term antidepressant maintenance treatment as clinically indicated. In terms of other potential treatment strategies, there is growing evidence to support the use of prazosin specifically for treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares (71). In addition, recent data suggest that adjunctive treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic agent may be helpful in patients with a partial response to an SSRI or other second-generation antidepressant. However, first-generation antipsychotics should not be used in the management of PTSD. Current evidence also recommends against long-term use of benzodiazepines to manage core PTSD symptoms or as monotherapy, especially given the potential for misuse/abuse and the lack of strong evidence of efficacy. There is, as yet, insufficient evidence to recommend the use of anticonvulsants or primary pharmacotherapeutic prophylaxis of PTSD.

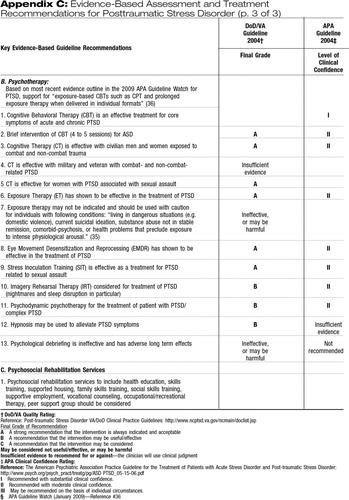

PSYCHOTHERAPY

There is strong RCT evidence supporting the use of exposure-based therapies including exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure therapy, and brief exposure therapy for civilians with PTSD exposed to trauma (both civilian and wartime) and for women with PTSD associated with sexual assault (34–36). Current recommendations suggest use of trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy as a first-line treatment for PTSD (36), which is typically delivered on an individual basis for 8–12 sessions of 90 minutes each (38). Exposure-based therapies, however, are not indicated and should be used with caution for “patients living in dangerous situations (e.g., domestic violence) or for patients with current suicidal ideation, substance abuse not in stable remission, comorbid psychosis, or health problems that preclude exposure to intense physiological arousal” (35).

RCT evidence has suggested that eye movement desensitization and reprocessing treatment may be efficacious for PTSD (36). There is also some RCT evidence supporting the use of stress inoculation therapy for PTSD related to sexual assault (36). Imagery Rehearsal Therapy may be considered for treating nightmares and sleep disruption associated with PTSD. There is strong evidence against the use of psychological debriefing as it may have long-term adverse consequences and has not shown any apparent benefit.

APPENDIX

APPENDICES A AND B: PERFORMANCE IN PRACTICE SAMPLE TOOLS

Appendices A and B provide sample PIP tools, each of which is designed to be relevant across clinical settings (e.g., inpatient, outpatient), straightforward to complete, and usable in a pen-and-paper format to aid adoption. Although the MOC program requires review of at least 5 patients as part of each PIP unit, it is important to note that larger samples will provide more accurate estimates of quality within a practice.

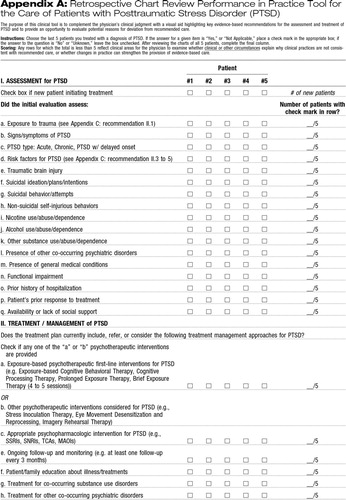

Appendix A provides a retrospective chart review PIP tool that assesses the care given to patients with PTSD. Although Appendix A is designed as a self-assessment tool, these forms could also be used for retrospective peer-review initiatives. As with other retrospective chart review tools, some questions on the form relate to the initial assessment and treatment of the patients whereas others relate to subsequent care. In general, treatment options for newly diagnosed patients who are being treated for the first time should judiciously follow the first-line evidence-based treatment recommendations. On occasion, however, there may be appropriate clinical reasons for deviation from recommended care including: patient's prior response or reaction to a similar class of pharmacologic agents, differential diagnoses, psychiatric or medical co-occurring conditions, and patient preferences.

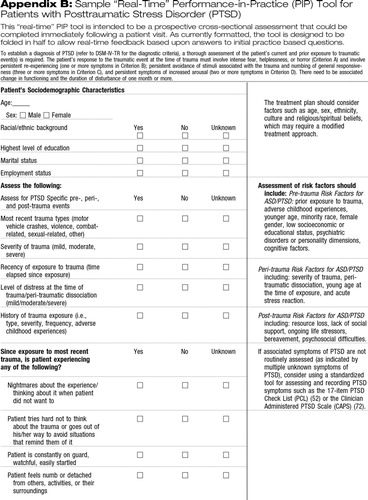

Appendix B provides a prospective review form. It is intended to provide a cross-sectional assessment that could be completed immediately following a patient's visit. As currently formatted, Appendix B is designed to be folded in half to allow real-time feedback based upon answers to the initial practice-based questions. This approach is more typical of clinical decision support systems that provide real-time feedback on the concordance between guideline recommendations and the individual patient's care. Such feedback provides the opportunity to adjust the treatment plan of an individual patient to improve patient-specific outcomes. In the future, the same data recording and feedback steps could be implemented via a web-based or electronic record system enhancing integration into clinical workflow. Data from this form could also be used in aggregate to plan and implement broader quality improvement initiatives. For example, if self-assessment using the sample tools suggests that signs and symptoms of PTSD are inconsistently assessed, consistent use of more formal rating scales such as the PTSD Checklist (PCL) (35, 52) could be considered.

Each of the sample tools attempts to highlight aspects of care that have significant public health implications (e.g., suicide, substance use disorders) or for which gaps in guideline adherence are common. Appendix C includes evidence-based recommendations derived from the APA (34, 36) and the VA/DoD (35) practice guidelines and summarizes specific aspects of care that are measured by these sample PIP tools. Quality improvement suggestions that arise from completion of these sample tools are intended to be within the control of individual psychiatrists rather than dependent upon other health care system resources.

After using one of the sample PIP tools to assess the pattern of care given to a group of 5 or more patients with PTSD, the psychiatrist should determine whether specific aspects of care need to be improved. For example, if the presence or absence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders has not been assessed or if these disorders are present but not addressed in the treatment plan, then a possible area for improvement would involve greater consideration of co-occurring psychiatric disorders, which are common in patients with PTSD.

These sample PIP tools can also serve as a foundation for more elaborate approaches to improving psychiatric practice as part of the MOC program. If systems are developed so that practice-related data can be entered electronically (either as part of an electronic health record or as an independent web-based application), algorithms can suggest areas for possible improvement using specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-limited objectives. Such electronic systems could also provide links to journal or textbook materials, clinical practice guidelines, patient educational materials, drug-drug interaction checking, evidence-based tool kits or other clinical materials. In addition, future work will focus on developing more standardized approaches to integrating patient and peer feedback with personal performance review, developing and implementing programs of performance improvements and reassessment of performance and patient outcomes.

|

Appendix A: Retrospective Chart Review Performance in Practice Tool for the Care of Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The purpose of this clinical tool is to complement the physician's clinical judgment with a visual aid highlighting key evidence-based recommendations for the assessment and treatment of PTSD and to provide an opportunity to evaluate potential reasons for deviation from recommended care.

Instructions: Choose the last 5 patients you treated with a diagnosis of PTSD. If the answer for a given item is “Yes,” or “Not Applicable,” place a check mark in the appropriate box; if the answer to the question is “No” or “Unknown,” leave the box unchecked. After reviewing the charts of all 5 patients, complete the final column.

Scoring: Any rows for which the total is less than 5 reflect clinical areas for the physician to examine whether clinical or other circumstances explain why clinical practices are not consistent with recommended care, or whether changes in practice can strengthen the provision of evidence-based care.

|

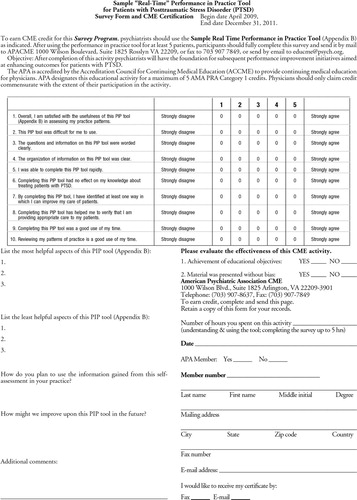

Appendix B: Sample “Real-Time” Performance-in-Practice (PIP) Tool for Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

This “real-time” PIP tool is intended to be a prospective cross-sectional assessment that could be completed immediately following a patient visit. As currently formatted, the tool is designed to be folded in half to allow real-time feedback based upon answers to initial practice based questions.

To establish a diagnosis of PTSD (refer to DSM-IV-TR for the diagnostic criteria), a thorough assessment of the patient's current and prior exposure to traumatic event(s) is required. The patient's response to the traumatic event at the time of trauma must involve intense fear, helplessness, or horror (Criterion A) and involve persistent re-experiencing (one or more symptoms in Criterion B); persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness (three or more symptoms in Criterion C), and persistent symptoms of increased arousal (two or more symptoms in Criterion D). There need to be associated change in functioning and the duration of disturbance of one month or more.

|

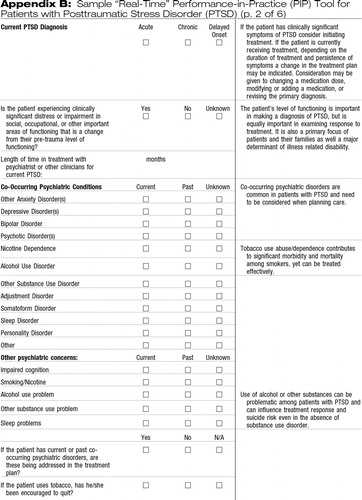

Appendix B: Sample “Real-Time” Performance-in-Practice (PIP) Tool for Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (p. 2 of 6)

|

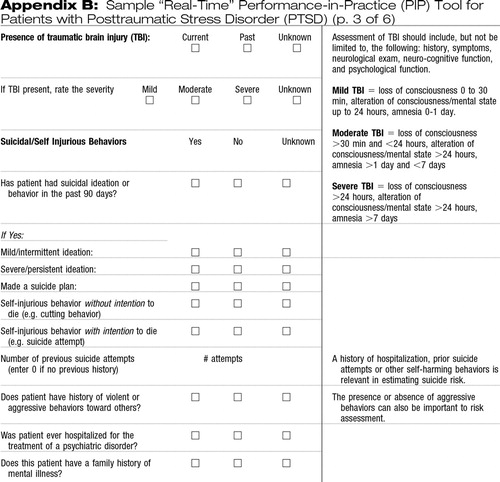

Appendix B: Sample “Real-Time” Performance-in-Practice (PIP) Tool for Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (p. 3 of 6)

|

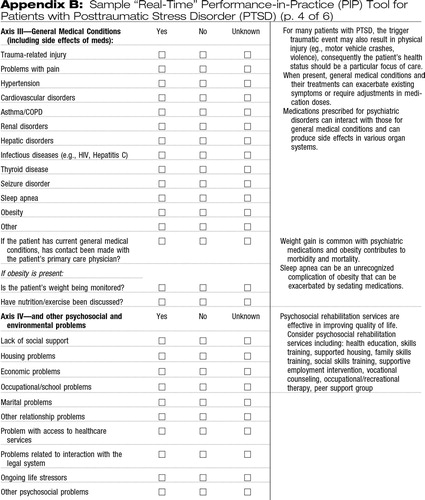

Appendix B: Sample “Real-Time” Performance-in-Practice (PIP) Tool for Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (p. 4 of 6)

|

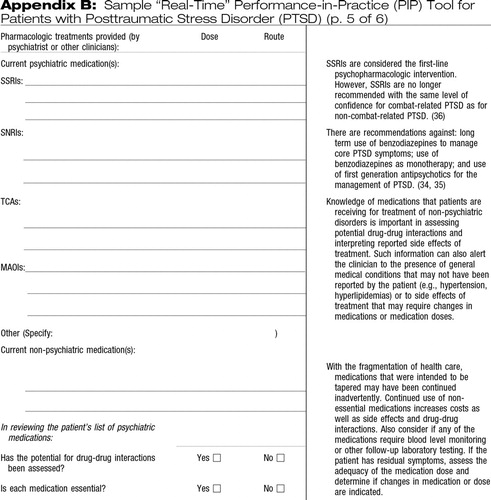

Appendix B: Sample “Real-Time” Performance-in-Practice (PIP) Tool for Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (p. 5 of 6)

|

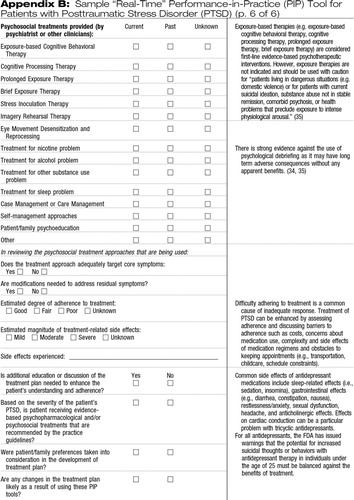

Appendix B: Sample “Real-Time” Performance-in-Practice (PIP) Tool for Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (p. 6 of 6)

|

Appendix C: Evidence-Based Assessment and Treatment Recommendations for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

|

Appendix C: Evidence-Based Assessment and Treatment Recommendations for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (p. 2 of 3)

|

Appendix C: Evidence-Based Assessment and Treatment Recommendations for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (p. 3 of 3)

|

Evaluation of the PIP Tool and CME Credit Form

DISCLOSURE OF OFF-LABEL USE OF MEDICATION

Medications discussed in this manuscript derived from the APA and the VA/DOD practice guidelines may not have an indication from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PTSD. To date sertraline and paroxetine are the only medications approved by the FDA to treat PTSD. Decisions about off-label use should be guided by the evidence provided in the APA or the Va/DoD practice guidelines, other scientific literature, and clinical experience. Medications which have not received FDA approval for any indication are not included in this manuscript.

1 Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001Google Scholar

2 Institute of Medicine: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2006Google Scholar

3 Colenda CC, Wagenaar DB, Mickus M, Marcus SC, Tanielian T, Pincus HA: Comparing clinical practice with guideline recommendations for the treatment of depression in geriatric patients: findings from the APA practice research network. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11: 448– 457Crossref, Google Scholar

4 West JC, Duffy FF, Wilk JE, Rae DS, Narrow WE, Pincus HA, Regier DA: Patterns and quality of treatment for patients with major depressive disorder in routine psychiatric practice. Focus 2005; 3: 43– 50Link, Google Scholar

5 Wilk JE, West JC, Narrow WE, Marcus S, Rubio-Stipec M, Rae DS, Pincus HA, Regier DA: Comorbidity patterns in routine psychiatric practice: is there evidence of under-detection and under-diagnosis? Compr Psychiatry 2006; 47: 258– 264Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Pincus HA, Page AE, Druss B, Appelbaum PS, Gottlieb G, England MJ: Can psychiatry cross the quality chasm? Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance use conditions. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 712– 719Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Rost K, Dickinson LM, Fortney J, Westfall J, Hermann RC: Clinical improvement associated with conformance to HEDIS-based depression care. Ment Health Serv Res 2005; 7: 103– 112Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Cochrane LJ, Olson CA, Murray S, Dupuis M, Tooman T, Hayes S: Gaps between knowing and doing: understanding and assessing the barriers to optimal health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007; 27: 94– 102Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Chen RS, Rosenheck R: Using a computerized patient database to evaluate guideline adherence and measure patterns of care for major depression. J Behav Health Serv Res 2001; 28: 466– 474Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Cabana MD, Rushton JL, Rush AJ: Implementing practice guidelines for depression: applying a new framework to an old problem. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002; 24: 35– 42Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Davis D: Does CME work? An analysis of the effect of educational activities on physician performance or health care outcomes. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998; 28: 21– 39Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Bloom BS: Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005; 21: 380– 385Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Chaillet N, Dubé E, Dugas M, Audibert F, Tourigny C, Fraser WD, Dumont A: Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108: 1234– 1245Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Ramsay C, Fraser C, Vale L: Toward evidence-based quality improvement: evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21( suppl 2): S14– S20Google Scholar

15 Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, Grilli R, Harvey E, Oxman A, O'Brien MA: Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care 2001; 39 8( suppl 2): II2– II45Google Scholar

16 Balas EA, Weingarten S, Garb CT, Blumenthal D, Boren SA, Brown GD: Improving preventive care by prompting physicians. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 301– 308Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Feldstein AC, Smith DH, Perrin N, Yang X, Rix M, Raebel MA, Magid DJ, Simon SR, Soumerai SB: Improved therapeutic monitoring with several interventions: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1848– 1854Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, Cooper JM, Paterno MD, Soukonnikov B, Goldhaber SZ: Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 969– 77Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Weingarten SR, Henning JM, Badamgarav E, Knight K, Hasselblad V, Gano A, Jr, Ofman JJ: Interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with chronic illness-which ones work? Meta-analysis of published reports. BMJ 2002; 325: 925Google Scholar

20 Arnold SR, Straus SE: Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 4: CD003539Google Scholar

21 Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM: Data feedback efforts in quality improvement: lessons learned from US hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care 2004; 13: 26– 31Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Paukert JL, Chumley-Jones HS, Littlefield JH: Do peer chart audits improve residents' performance in providing preventive care? Acad Med 2003; 78( 10 suppl): S39– S41Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Sohn W, Ismail AI, Tellez M: Efficacy of educational interventions targeting primary care providers' behaviors: an overview of published systematic reviews. J Public Health Dent 2004; 64: 164– 172Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Grol R: Changing physicians' competence and performance: finding the balance between the individual and the organization. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2002; 22: 244– 251Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Oxman TE: Effective educational techniques for primary care providers: application to the management of psychiatric disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998; 28: 3– 9Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Green LA, Wyszewianski L, Lowery JC, Kowalski CP, Krein SL: An observational study of the effectiveness of practice guideline implementation strategies examined according to physicians' cognitive styles. Implement Sci 2007; 2: 41Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Roumie CL, Elasy TA, Greevy R, Griffin MR, Liu X, Stone WJ, Wallston KA, Dittus RS, Alvarez V, Cobb J, Speroff T: Improving blood pressure control through provider education, provider alerts, and patient education: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 145: 165– 175Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Hysong SJ, Best RG, Pugh JA: Clinical practice guideline implementation strategy patterns in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Health Serv Res 2007; 42: 84– 103Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Dykes PC, Acevedo K, Boldrighini J, Boucher C, Frumento K, Gray P, Hall D, Smith L, Swallow A, Yarkoni A, Bakken S: Clinical practice guideline adherence before and after implementation of the HEARTFELT (HEART Failure Effectiveness & Leadership Team) intervention. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 20: 306– 314Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Greene RA, Beckman H, Chamberlain J, Partridge G, Miller M, Burden D, Kerr J:. Increasing adherence to a community-based guideline for acute sinusitis through education, physician profiling, and financial incentives. Am J Manag Care 2004; 10: 670– 678Google Scholar

31 American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology: Maintenance of certification for psychiatry. 2007. http://www.abpn.com/moc_psychiatry.htmGoogle Scholar

32 Institute of Medicine: Health Professions Education: a Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2003Google Scholar

33 Miller SH: American Board of Medical Specialties and repositioning for excellence in lifelong learning: maintenance of certification. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2005; 25: 151– 156Crossref, Google Scholar

34 American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideHome.aspx Google Scholar

35 Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense: VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of post-traumatic stress. 2004. http://www.pdhealth.mil/clinicians/va-dod_cpg.aspGoogle Scholar

36 Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, Ursano RJ: Guideline watch (March 2009): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://www.psychiatryonline.com/content.aspx?aID=156514Google Scholar

37 Forbes D, Creamer M, Phelps A, Bryant R, McFarlane A, Devilly GJ, Matthews L, Raphael B, Doran C, Merlin T, Newton S: Australian guidelines for the treatment of adults with acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007; 41: 637– 648Crossref, Google Scholar

38 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Clinical Guideline 26. London, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2005. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG026NICEguidelineGoogle Scholar

39 Fochtmann LJ, Duffy FF, West JC, Kunkle R, Plovnick RM: Performance in practice: sample tools for the care of patients with major depressive disorder. Focus 2008; 6: 22– 35Link, Google Scholar

40 American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157( 4 suppl): 1– 45Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Eddy D: Reflections on science, judgment, and value in evidence-based decision making: a conversation with David Eddy by Sean R. Tunis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007; 26: w500– w515Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Kobak KA, Taylor L, Katzelnick DJ, Olson N, Clagnaz P, Henk HJ: Antidepressant medication management and Health Plan Employer Data Information Set (HEDIS) criteria: reasons for non-adherence. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 727– 732Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Zarin DA, Young JL, West JC: Challenges to evidence-based medicine: a comparison of patients and treatments in randomized controlled trials with patients and treatments in a practice research network. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005; 40: 27– 35Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Hofer TP, Hayward RA, Greenfield S, Wagner EH, Kaplan SH, Manning WG: The unreliability of individual physician “report cards” for assessing the costs and quality of care of a chronic disease. JAMA 1999; 281: 2098– 2105Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Kahn R, Ninomiya J, Griffith JL: Profiling care provided by different groups of physicians: effects of patient case-mix (bias) and physician-level clustering on quality assessment results. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 111– 121Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Parkerton PH, Smith DG, Belin TR, Feldbau GA: Physician performance assessment: nonequivalence of primary care measures. Med Care 2003; 41: 1034– 1047Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Lipner RS, Weng W, Arnold GK, Duffy FD, Lynn LA, Holmboe ES: A three-part model for measuring diabetes care in physician practice. Acad Med 2007; 82( 10 suppl): S48– S52Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Nietert PJ, Wessell AM, Jenkins RG, Feifer C, Nemeth LS, Ornstein SM: Using a summary measure for multiple quality indicators in primary care: the Summary QUality InDex (SQUID). Implement Sci 2007; 2: 11Google Scholar

49 Kessler RC, Sonnega A Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52: 1048– 1060Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Elhai JD, Grubaugh AL, Kashdan TB, Frueh BC: Empirical examination of a proposed refinement to DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder symptom criteria using the National Comorbidity Survey Replication data. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69: 597– 602Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis G, Andreski P: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55: 626– 632Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Norris FH, Hamblen JL: Standardized self-assessment measures of civilian trauma and PTSD, Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner's Handbook, 2nd ed. Edited by Wilson J, Keane T. New York, Guilford, 2003. http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/ncmain/ncdocs/assmnts/ptsd_checklist_pcl.htmlGoogle Scholar

53 Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 13– 22Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C: Incidence and prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in severely injured accident victims. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 594– 599Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Silva RR, Alpert M, Munoz DM, Singh S, Matzner F, Dummit S: Stress and vulnerability to posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1229– 1235Crossref, Google Scholar

56 DiGrande L, Perrin MA, Thorpe LE, Thalji L, Murphy J, Wu D, Farfel M, Brackbill RM: Posttraumatic stress symptoms, PTSD, and risk factors among lower Manhattan residents after the Sept 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. J Trauma Stress 2008; 21: 264– 273Crossref, Google Scholar

57 North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Tivis L, Kawasaki A, Reddy C, Spitznagel EL: The course of posttraumatic stress disorder in a follow-up study of survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2004; 16: 209– 215Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Galea S, Tracy M, Norris F, Coffey SF: Financial and social circumstances and the incidence and course of PTSD in Mississippi during the first two years after Hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress 2008; 21: 357– 368Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Wang X, Gao L, Shinfuku N, Zhang H, Zhao C, Shen Y: Longitudinal study of earthquake-related PTSD in a randomly selected community sample in North China. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1260– 1266Crossref, Google Scholar

60 McKibben JB, Bresnick MG, Wiechman Askay SA, Fauerbach JA: Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a prospective study of prevalence, course, and predictors in a sample with major burn injuries. J Burn Care Res 2008; 29: 22– 35Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Mehnert A, Koch U: Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary care: a prospective study. Psychooncology 2007; 16: 181– 188Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Wikman A, Bhattacharyya M, Perkins-Porras L, Steptoe A: Persistence of posttraumatic stress symptoms 12 and 36 months after acute coronary syndrome. Psychosom Med 2008; 70: 764– 772Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Zatzick D, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Wang J, Fan MY, Joesch J, Mackenzie E: A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Ann Surg 2008; 248: 429– 437Google Scholar

64 Andrews B, Brewin C, Philpott R, Stewart L: Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1319– 1326Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Neria Y, Bromet EJ, Sievers S, Lavelle J, Fochtmann LJ: Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in psychosis: findings from a first admission cohort. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70: 246– 251Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Spitzer C, Barnow S, Volzke H, John U, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the elderly: findings from a German community study. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69: 693– 700Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Mellman TA, Randolph CA, Brawman-Mintzer O, Flores LP Milanes FJ: Phenomenology and course of psychiatric disorders associated with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149: 1568– 1574Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Thatcher JW, Marchand WR, Thatcher GW, Jacobs A, Jensen C: Clinical characteristics and health service use of veterans with comorbid bipolar disorder and PTSD. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58: 703– 707Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Zarin DA, McIntyre JS, Pincus HA, Seigle, L: Practice guidelines in psychiatry and a psychiatric practice research network, in Textbook of Psychiatry. Edited by Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1999Google Scholar

70 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Diagnosis and Assessment. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2006Google Scholar

71 Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, Hart KL, Warren D, Shofer J, O'Connell J, Taylor F, Gross C, Rohde K, McFall ME: A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61: 928– 934Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LN, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TN: Clinician-administered PTSD scale, in Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, 2nd Edition. Edited by Rush AJ, First MD, Blacker D. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 2008. http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/ncmain/ncdocs/assmnts/clinicianadministered_ptsd_scale_caps.htmlGoogle Scholar