Psychiatric Assessment and Diagnosis in Older Adults

Abstract

To provide optimal care, the approach to psychiatric evaluation and diagnosis in older adults requires special attention to several issues. There are important biological, psychological, and social changes associated with either aging itself or with generational differences. In this review, we will address some of the most important aspects of assessment and diagnosis that make geriatric psychiatry a unique subspecialty, including age-related variability in the clinical presentation of common psychiatric disorders, assessment and diagnosis of cognitive disorders and medical comorbidity, and common psychosocial challenges faced by older adults. Although geriatric psychiatrists are uniquely positioned to address the complexities of psychiatric illness in older adults, the fact remains that the majority of older adults who seek psychiatric care will see general adult psychiatrists without subspecialty training. However, with continued vigilance to the issues outlined below, psychiatrists from a variety of training backgrounds can skillfully assess and diagnose psychiatric illnesses in older adults.

PSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS IN OLDER ADULTS

DIAGNOSTIC CONUNDRUMS IN THE ELDERLY

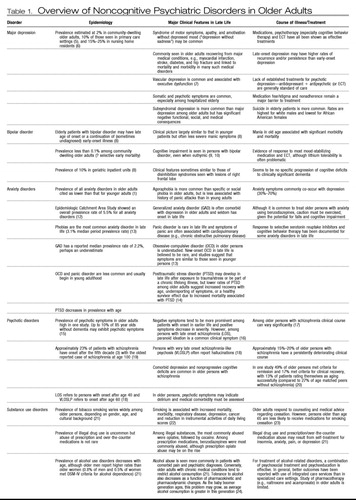

There is some confusion in the psychiatric literature regarding the incidence, prevalence, and illness course of psychiatric disorders in late life. This can be partly attributed to a paucity of studies focused on determining the epidemiology of psychiatric illnesses in older adults (2). Moreover, there is a common belief (and some empirical evidence) that psychiatric disorders (except dementia) are less prevalent in older adults than in younger populations (3). Yet, these studies have certain limitations. Behavioral and neurovegetative symptoms of psychiatric illness frequently overlap with those of general medical conditions, and increasing age is generally accompanied by increased medical comorbidity, which creates diagnostic conundrums in the evaluation of older adults. In addition, age-related changes in the body and brain, as well as cohort effects, can lead to atypical manifestations of psychiatric illness, resulting in inaccurate or overlooked psychiatric diagnosis (4). Increasingly, however, it is recognized that special care needs to be given to psychiatric assessment of the older patient. Awareness and subsequent clinical recognition of the differences in symptoms between older and younger age groups may help reduce both psychiatric and medical comorbidity. Table 1 outlines age-related differences in the clinical features of several major psychiatric illnesses. Estimates of incidence and prevalence as well as prognosis and illness course are included.

|

Table 1. Overview of Noncognitive Psychiatric Disorders in Older Adults

NEED FOR AGE-SPECIFIC DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA IN PSYCHIATRY

It is important to note that available information on psychiatric disorders in older adults is based on research conducted using diagnostic criteria from either the DSM or ICD, both of which were almost invariably developed from models of illness in mostly younger or middle-aged adults. However, it has become increasingly evident that use of these criteria may result in an underestimation of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in older persons, largely because these criteria have not been validated in older populations (25). Symptoms of psychiatric illness in older adults do not always correspond with criteria described in the standard diagnostic manuals, a phenomenon also seen and more widely recognized among children and adolescents. Ultimately, as research on age-related changes in the brain expands, we will gain a more sophisticated understanding of differences in clinical symptoms of psychiatric illness as a function of age. Creating age-specific diagnostic criteria on the basis of evolving knowledge of this process will allow clinicians to better identify symptoms, diagnose illness, and devise treatments for management of late-life psychiatric disorders. For now, awareness of variable presentations of psychiatric disorders in older adults, as reviewed in Table 1, enables the clinician to be more attuned to the psychiatric needs of older adults.

COGNITIVE AND FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT OF OLDER ADULTS

AGING AND COGNITION

Unlike the disorders described in Table 1, cognitive disorders are unequivocally more prevalent as age increases, and competency in assessing cognition is an essential skill for clinicians caring for older adults. This encompasses the use of cognitive screening assessments, early detection and education about dementias, treatment of comorbid disorders that masquerade as dementia, attention to family system and caregiver issues, referral to and collaboration with other professionals such as neurologists and neuropsychologists, and reassurance when cognitive changes are the result of normal aging.

There is a common public (and even professional) misconception that dementia is a sine qua non of aging. Although age is the most prominent risk factor for dementia, half or more of adults older than age 85 retain normal cognitive functioning (26). Cognitive impairments that meet the diagnostic criteria for dementia should never be dismissed as normal aging. Nonetheless, it is also valuable to recognize that there are some changes in cognition that are age-related and not considered pathological. Examples of such age-related cognitive changes include some decline in free recall and consistently slower processing speed. However, more crystallized abilities (vocabulary and general knowledge) tend to remain stable or even, in some circumstances, increase with age (27). When appropriate, reassurance about benign cognitive changes of aging can allay significant anxiety for older adults, who are increasingly cognizant of illnesses such as Alzheimer's disease.

COGNITIVE ASSESSMENTS

The most widely recognized standardized cognitive assessment used in clinical settings is the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (28). The MMSE is useful primarily as a screening tool, although it may also be used as a crude proxy for illness progression in persons with dementia. Cutoffs for “normal” versus “abnormal” scores vary by age and educational attainment (29), in addition to possible cultural variations (30). Criticisms of the MMSE have included a relative lack of assessment of certain cognitive domains (e.g., executive functioning) and insensitivity to early dementia, especially in older adults with high intelligence and educational attainment (31).

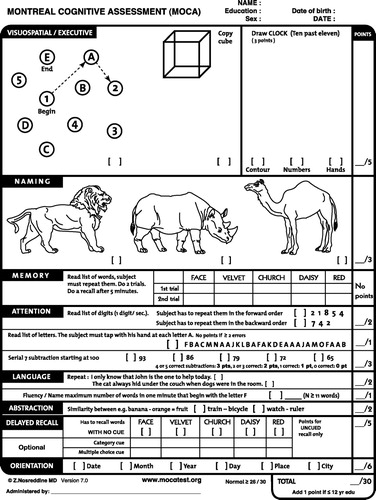

Other screening cognitive tests have been developed to address possible limitations of the MMSE. The Mini-Cog Test, which uses only three-item registration and recall separated by the Clock Drawing Test, is somewhat quicker to administer than the MMSE, and is useful in certain settings such as primary care and the emergency room, and appears to have sensitivity and specificity for dementia similar to that of the MMSE (32). Other examples include the Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (33) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (34) (Figure 1), which have more extensive memory and executive function assessment than the MMSE.

Figure 1. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

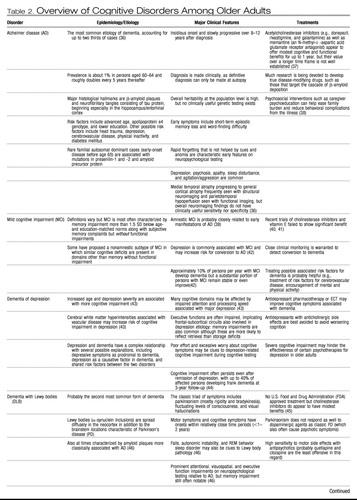

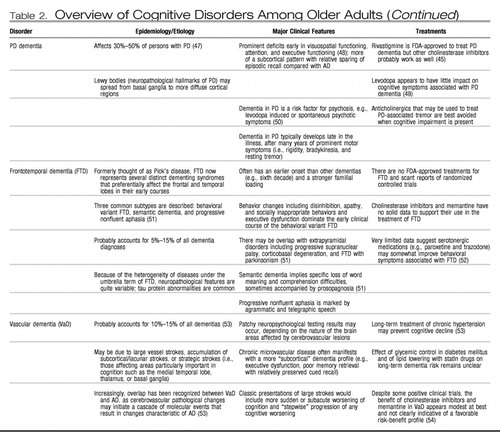

The gold standard of cognitive assessment is formal neuropsychological testing, typically performed by a specialist in neuropsychology. Referral for neuropsychological testing may be particularly useful if diagnosis is uncertain (e.g., early Alzheimer disease versus dementia of depression), as various forms of dementia exhibit somewhat distinct profiles of relative strengths and impairments early in the course of illness (35). Table 2 lists the most common variants of cognitive disorders among older adults, along with clinically distinguishing features including typical neuropsychological profiles. In moderate-to-severe stages, most forms of dementia eventually cause diffuse and nonspecific impairment across multiple cognitive domains. One must also keep in mind that the most troubling symptoms of dementia are often the accompanying psychological and behavioral changes, which affect up to 80% of persons with dementia across the illness course and which frequently increase caregiver burden and the likelihood of patient institutionalization (55). Evaluation for depressive symptoms, psychosis, sleep disturbance, and agitation is a crucial part of the evaluation of cognitive disorders in older adults, and progress is being made toward establishing reliable diagnostic categorization of such neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia (56).

|

|

Table 2. Overview of Cognitive Disorders Among Older Adults

There are several traditionally distinct (although admittedly sometimes overlapping) cognitive domains that can be assessed with neuropsychological testing, and abbreviated assessments of each domain are also possible in the clinical setting. Some of the most frequent cognitive domains as conceptualized by neuropsychology today are described below:

| 1. | Crystallized knowledge includes abilities that are relatively unaffected by aging and are related to acquired knowledge, such as the meanings of words and general facts. Example of crystallized knowledge assessments are vocabulary tests (e.g., Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test) (57), general knowledge tests (e.g., Wechsler Scales Information Subtest) (58), or regular and irregular word reading tests (e.g., Wide Range Achievement Test) (59). Office testing of general knowledge may include inquiring about current and past presidents or famous world events, although cultural differences should always be considered in such assessments. | ||||

| 2. | Processing speed decrements are among the most consistent age-related cognitive changes. Assessments include the Trail Making Test Part A (60) and Digit Symbol Coding (61). | ||||

| 3. | Attention is a very broad concept encompassing a range of skills, from keeping track of information to responding to targets over long periods of time (vigilance). This may be assessed in a variety of ways such as the Continuous Performance Test (62). Office-based cognitive screens often include an assessment of attention (e.g., repeating digits or spelling words backward). Impairment in attention could drastically alter test results for any other cognitive domain, at times rendering other tests uninterpretable. | ||||

| 4. | Receptive and expressive language refers to a person's abilities to understand what is being said and respond in an appropriate manner (either orally or written), respectively. One of the most common receptive language tasks is the Token Test (ability to follow instructions) (63), with fluency tasks (category or letter fluency) (64) or naming tasks (e.g., Boston Naming Test) (65) being commonly used expressive language tasks. | ||||

| 5. | Visuospatial and constructional skills encompass the ability to identify objects and shapes and to draw in a coherent manner. Most of these tasks require some amount of physical dexterity, whether constructing jigsaw puzzles (Wechsler's Object Assembly), making patterns from colored blocks (Wechsler's Block Design) (53), or drawing complex figures (Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test) (66). | ||||

| 6. | Memory includes many subtypes but neuropsychological testing typically assesses episodic memory, i.e., memory of events, times, or places related to unique personal experiences. This may be done in verbal or visual domains, over short or long delays, and with a variety of tasks (e.g., Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Task or California Verbal Learning Test) (67, 68). Working memory is generally regarded as a distinct concept akin to attention and referring more to the ability of a person to manipulate information in his or her short term memory (69). Some common tests of working memory are the Wechsler subscales for Digit Span and Letter-Number Sequencing (58). | ||||

| 7. | Executive function is a widely used concept that is difficult to define, because it encompasses so many different concepts (e.g., set shifting, fluency, pattern recognition, mental flexibility, and inhibition) (70). Classic tests of executive function include the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (pattern recognition and set shifting) (71), the Trail Making Test Part B (set shifting), and the Stroop Tasks (response inhibition) (72). | ||||

Cognitive testing of older adults should be conducted with several caveats in mind. For example, there is a lack of age-appropriate normative data on many tests for the oldest-old age groups and certain cultural groups. Many older people have sensory or motor impairments that may interfere with certain tasks independently from cognition per se. Subtle cognitive deficits may be very difficult to detect, especially in high-functioning or highly educated older adults. Even the best of cognitive testing may leave questions unanswered, and in these circumstances the trajectory of change in cognition over time can be very informative.

CAPACITY/COMPETENCE

Clinicians may often be asked to evaluate the decision-making capacity of older adults. Competency usually refers to an evaluation derived from legal adjudication. Decisional capacity is the preferred term when describing a clinician's evaluation of a patient's decision-making abilities. Evaluation of decisional capacity is most commonly prompted when a patient declines a recommended treatment (73). Two other common scenarios involve capacity to drive and to decide on one's living environment (74). Clinicians are required in a few and allowed in most states to report cases of dementia to motor vehicle departments. There is no clinical consensus for how to determine when a person should have his or her driver's license revoked. Although the safety of the public and patient is clearly important, this must be balanced with the possible adverse consequences of license revocation on a person's sense of independence and practical mobility. On-road driving tests may represent the best available option in questionable cases. Equally contentious at times is the dilemma of when an older adult needs to enter a structured living environment (i.e., assisted living or nursing home), also reflecting basic ethical conflicts between paternalism and respect for autonomy.

Older adults are certainly at increased risk for impaired decisional capacity. Dementia is often the most prominent illness in clinicians' minds when considering impaired decisional capacity. Psychosis and depression may also impair decisional capacity in older adults via emotional factors, such as paranoid delusions or severe hopelessness. However, psychiatric illness and dementia do not invariably impair decisional capacity (75, 76). Several qualities have been consistently described as necessary for decisional capacity. The four most commonly cited criteria are

1) consistent communication of a choice,

2) factual understanding,

3) appreciation of a situation and potential consequences of a decision, and

4) rational manipulation of information (77).

FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENTS

Psychiatry is perhaps unique among medical specialties in that it has traditionally emphasized functional impairment as part of its disease constructs, but functional assessments are especially germane in the evaluation of older adults and are an essential component of what distinguishes geriatrics as a subspecialty (78). Functional impairment increases with age and is often overlooked or marginalized in importance if one focuses too narrowly on symptomatology. All psychiatric assessments of older adults should include a basic history of functioning in both instrumental (e.g., driving, cooking, and managing finances) and basic (e.g., grooming, eating, and walking) activities of daily living. Standardized assessments are available as well, including the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale (79) and the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (80).

Given the link between the use of most psychotropic medications and increased risk for falls (81), specific assessments of mobility may also be useful for psychiatrists caring for older adults. Perhaps the simplest and most sensitive screening for fall risk is the Timed Get-Up and Go Test (82). This test entails asking the patient to rise from a chair without using his or her arms, walk about 10 feet, turn around, and sit back down (again without using his or her arms). If the patient takes more than 10 seconds to complete the examination or exhibits obvious unsteadiness, then further evaluation of gait and balance is indicated.

MEDICAL ASSESSMENT OF OLDER ADULTS WITH PSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS

Nowhere is the mind-body connection more evident than in the psychiatric assessment of older adults. Although a medical assessment is an integral part of the initial evaluation for all persons presenting with psychiatric symptoms, it is especially important for older adults. Older adults are at increased risk for delirium (83), polypharmacy (84), and many medical conditions, all of which can present primarily or even exclusively with psychiatric symptoms. As providers with both psychological and medical training, psychiatrists are uniquely positioned to provide an integrated medical and psychological evaluation of the older adult presenting with behavioral or psychological symptoms. Even when a medical disorder is not the direct physiological cause of psychiatric illness, the impact of chronic medical illness on quality of life and functional ability is often apparent in the lives of older adults and relevant to psychiatric assessment and treatment (85). For instance, medical illness is associated with increased risk for suicide among older adults (86).

As with any medical or psychiatric assessment, the best approach is to start with a thorough history. A medical history is, of course, part of any psychiatric evaluation. We will therefore highlight some special considerations to keep in mind in the initial psychiatric assessment of older adults. Always consider obtaining collateral information, particularly when patients exhibit any cognitive impairment (87). Even cognitively intact older adults may withhold or fail to recognize important historical information that family members can provide, although balancing the relative validity of contradictory perspectives requires consideration of several possible competing motivations and family dynamics.

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS

Given the prevalence of delirium and psychiatric illness due to a medical condition in late life, it is important for a clinician to keep these diagnoses at the top of the differential diagnosis when conducting psychiatric evaluations of older adults (88). Obtaining a thorough understanding of the time course of the psychiatric symptoms can be one of the best clues as to whether delirium or a medical condition is implicated in the etiology (e.g., increased suspicion for a medical etiology when symptom onset is acute or when new physical symptoms overlap chronologically with new psychiatric symptoms) (87). Some cases may be readily apparent (e.g., confusion and hallucinations accompanying 2 days of fever and cough associated with pneumonia), but many require a higher level of vigilance (e.g., depression associated with hypercalcemia due to an occult parathyroid adenoma) (89). There may also be complex reciprocal relationships between medical conditions and psychiatric symptoms (e.g., the interplay between anxiety and dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) (90).

The nature and pattern of psychiatric symptoms may also yield clues as to whether they may be due to medical illness. For example, visual, olfactory, or tactile (versus auditory) hallucinations increase suspicion for medical causes (91). Early morning awakening is a classic symptom of melancholic depression, whereas repeated nighttime awakenings often occur with nocturia due to benign prostatic hypertrophy, persistent pain, or severe gastroesophageal reflux (92). In addition, cognitive impairment accompanied by inattention and an altered level of consciousness points toward delirium, often underrecognized as a medical emergency (83).

PAST PSYCHIATRIC HISTORY

Most primary psychiatric illnesses (other than cognitive disorders) manifest well before old age, such that the first episode of an illness after age 40 significantly raises suspicion for an underlying medical problem (93). As in the history of present illness, one should assess whether prior symptoms or episodes could have been related to medical illness. If no prior link to medical illness is identified, it is, of course, important to remember—and remind our medical colleagues—that previous psychiatric illness does not preclude delirium or psychiatric illness due to a medical condition being part of the current presentation.

SUBSTANCE USE HISTORY

Although often overlooked in older adults, substance abuse, particularly alcohol and prescription drug abuse (94, 95), is an important potential contributor to medical and psychiatric problems. Thus, it is always worth evaluating whether substance intoxication, withdrawal (especially postoperatively), abuse, or dependence could be contributing to an older adult's presenting psychiatric symptoms. A lifetime of substance use may lead to multiple medical sequelae in older adults (96, 97), including various cancers, nutritional deficiencies, and organ failure, all of which may themselves cause secondary cognitive and psychological symptoms.

MEDICAL HISTORY

Some of the most relevant disorders to investigate, because of their contribution to neuropsychiatric symptoms and/or their high comorbidity with psychiatric illnesses include endocrine disorders (e.g., hypo-/hyperthyroidism, hypo-/hyperparathyroidism, and diabetes mellitus) (98), cardiovascular disorders (e.g., coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease) (99), and rheumatological disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and polymyalgia rheumatica) (100). Persistent pain disorders are quite common in older adults, are often comorbid with anxiety and depression, and may increase suicide risk (101, 102). Taking a sexual history may seem uncomfortable or unnecessary with older adults, but this reluctance reflects an ageist attitude. Sexual functioning is often an important component of the physical and emotional health of older adults, and many psychotropic medications may adversely affect sexual desire and/or performance.

MEDICATIONS

One of the best contributions a physician can make to an older adult's care is a thorough review of all his or her medications (84). Iatrogenic psychiatric symptoms can arise from medication side effects and drug-drug interactions but often go undetected (103). Medication assessments should include obtaining a full list of all medications the patient is taking including over-the-counter and herbal medications and supplements, assessing dosing schedules, determining how often patients are really taking medications (looking for over- and underuse), asking about side effects, and checking for drug-drug interactions (104). If potential problems, such as unnecessary or redundant medications or possible psychiatric side effects, are identified, working with a patient's primary care physician or team to minimize these problems can be invaluable in improving an older adult's medical and psychiatric condition. Particular attention should be given to minimizing the cumulative anticholinergic burden of medications in older adults, often the result of several concomitant medications whose anticholinergic effects are underrecognized (105). Geriatric care is often as much or more about removing iatrogenic culprits of illness as prescribing additional treatments.

EXAMINATION

Although psychiatrists typically do not do physical examinations as part of their initial medical assessment, these may be appropriate under certain circumstances. Certainly routine vital signs, including pain severity, weight, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements, may identify medical conditions that may alter one's diagnosis or treatment as well as potentially serious side effects of psychotropic drugs (e.g., anticholinergic or proadrenergic drug-induced tachycardia predisposing to cardiac complications, antiadrenergic-induced orthostasis predisposing to falls, and medication-associated weight gain or loss predisposing to a host of adverse medical consequences) (106, 107). Although vital signs may be an important clue to medical emergencies, one must also keep in mind age-associated changes in the physiology of vital signs (e.g., infection in the absence of fever or increased carotid sinus sensitivity) (108, 109).

Examinations for tardive dyskinesia and parkinsonism are particularly important when a clinician is prescribing antipsychotics for older adults, given that age increases the risk of these motor complications (110). The mental status examination of older adults consists largely of the same components included in the assessment of younger adults, with the notable exception that more extensive cognitive assessment, including evaluation for delirium, is often needed. Evaluation for suicidal ideation should be at the forefront of clinical assessments in light of the elevated rates of completed suicide among older adults, mostly accounted for by white men (111).

LABORATORY TESTING AND IMAGING

Depending on an older adult's presentation and the treatment options being considered, a variety of laboratory tests may be indicated in the medical assessment of an older adult presenting with psychiatric symptoms. Laboratory tests to consider routinely obtaining include the following: 1) thyroid function tests (e.g., thyroid-stimulating hormone), because thyroid disease may cause depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment (112); 2) electrolyte levels, because alterations of these may significantly affect the central nervous system (e.g., hyponatremia-induced delirium due to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment) (113); 3) renal function tests (blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine), because renal function is often reduced by age or age-associated illness, which may significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of medications (114); 4) hepatic function tests (e.g., alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase), because psychopathological conditions may significantly contribute to chronic liver disease via alcohol use and comorbid hepatitis C infection (115); 5) complete blood count, because anemia may explain fatigue/depression, leukocytosis may point to an undetected infection, and many psychotropic drugs have hematopoietic side effects (116); 6) lipid panel and fasting glucose, particularly if a patient is already taking or considering starting medications that could cause metabolic syndrome (117); 7) rapid plasma reagin to test for syphilis and HIV antibodies if the patient has risk factors and consents, because prejudicial views of older adults may lead clinicians to dismiss their current or past sexual activity (118); 8) urine drug screen to assess for substance use and breathalyzer or blood alcohol level, especially in emergency room settings, where, again, age may inappropriately lower clinicians' vigilance for substance use (95); 9) urinalysis, because urinary tract infection may present exclusively with mental status changes in older adults (119); 10) vitamin B12 and folate levels, because deficiencies of these increase with age and may contribute to both depression and cognitive impairment (42); and 11)drug levels of any prescription drugs patients are taking, especially those with low therapeutic indices (e.g., lithium, anticonvulsants, digoxin, and tricyclic antidepressants).

Other diagnostic tests to be considered in certain situations include the following: 1) chest radiograph for respiratory symptoms, signs of delirium, or fever; 2) neuroimaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography) to evaluate for stroke, mass lesions, or normal pressure hydrocephalus (120); 3) electrocardiogram for acute mental status change, cardiorespiratory symptoms, or consideration of psychotropic agents that may alter cardiac conduction (e.g., lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, and certain antipsychotics) (121); 4) electroencephalogram for paroxysmal symptoms that could be due to seizures, unusual or subacute dementias (e.g., Creutzfeld-Jacob disease), or diagnostic confusion between delirium versus dementia (although generalized slowing is present in both delirium and more advanced cases of dementia) (122); and 5) lumbar puncture in patients with atypical cognitive disorders, fever without a clear etiology, or suspected neurosyphilis (123).

Many invasive (e.g., lumbar puncture) or expensive (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging) tests may be unnecessary with a careful history and physical examination. Although the use of neuroimaging is clinically routine in the assessment of delirium, dementia, and late-onset psychiatric disorders, there is debate as to its cost-effectiveness and clinical yield in the absence of historical (e.g., acute onset) or physical examination findings (e.g., focal neurological symptoms) that raise suspicion for certain neurological disorders (124, 125). The explosion of research in functional neuroimaging has yet to yield significant clinical applications, although this is anticipated in upcoming years with promising techniques such as in vivo amyloid imaging (126). Currently, the only psychiatric application of functional neuroimaging approved by Medicare is the use of positron emission tomography in differentiating Alzheimer-type versus frontotemporal dementia in patients with clinically unclear illness (127).

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF OLDER ADULTS

Although medical disorders and neurobiological changes associated with aging are at the forefront of considerations in psychiatric assessments of older adults, a balanced biopsychosocial perspective remains crucial as well. The comfort level of older adults (at least the current cohort) with mental illness and psychiatric evaluation must be considered to develop the rapport needed for any other aspect of assessment (128). Older adults also tend to face somewhat unique psychosocial stressors that may have tremendous relevance for the symptoms at hand. For instance, acting as a caregiver for a disabled relative is associated with high rates of depression and is often used in research as a prototypical model of stress (129). Accumulating medical (and at times psychiatric or cognitive) illnesses often result in disability and loss of independence (including forced moves to senior living communities) that challenge the resilience and self-concepts of older adults. Other forms of loss, including deaths of friends and family, are common, and grief reactions may ensue that warrant careful attention for clinically significant depressive symptoms (130). DSM-IV-TR (131) outlines several features that are believed to help distinguish normal versus abnormal bereavement, such as suicidal ideation, persistent worthlessness, and severe, persistent functional impairment. Such losses and personal disabilities may trigger psychological struggles regarding one's own mortality that may be very relevant in psychotherapy with older adults, but clinicians often avoid this topic because of discomfort (132). Another sometimes surprising stressor for older adults is retirement, which may challenge persons whose self-identity and structured activities center around their occupation (133). Although these challenges confronting older adults may seem daunting, it is also worthwhile to note the positive coping strategies used by many older adults so that clinicians also work to facilitate the person's innate strengths. Possible psychological benefits of increased age include, on average, better emotional regulation (134) and, according to many cultural beliefs, increased wisdom (135).

For these and other reasons, social support is an important predictor of the health outcomes of older adults (136, 137). Psychiatric assessment and care of older adults thus requires careful attention to social networks and often includes family members in the assessment and treatment of the older adult in a manner akin to that used for children and adolescents (with important similarities and differences in the dynamics encountered, including struggles for autonomy and role reversals). The increasing diversity of the aging population in the United States also warrants increasing attention to culturally competent psychiatric assessments, including awareness of linguistic barriers, differing cultural concepts of both aging and illness, and possible roadblocks to health care access (138).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, psychiatric assessment of older adults is both challenging and rewarding. Therapeutic nihilism and ageism may taint the enthusiasm some clinicians have for working with older adults affected by neuropsychiatric illness, but careful attention to the issues summarized briefly in this review can help ensure that such clinical experiences are rewarding for both older patients and the clinicians who care for them. Psychiatric assessment of older adults should remind psychiatrists of why they are often called upon to set the example for biopsychosocial care in clinical medicine. Medical comorbidity requires attention to clinical issues that overlap with other fields of medicine, unique psychosocial stressors, and the stigma of mental illness associated with aging require careful attention to the human relationship between clinician and patient, and the importance of social support and extended family involvement call for a broad, systems-based approach to the psychiatric care of older adults. Integrating these various components of assessment and diagnosis will be crucial for the wide variety of psychiatrists who will be increasingly called upon to care for the rapidly expanding population of older adults.

1 Gruenberg EM: The failures of success. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc 1997; 55: 3– 24Google Scholar

2 Hybels C, Blazer D: Epidemiology and Geriatric Psychiatry in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Edited by Tsuang M, Tohen M. New York, NY, John Wiley & Sons, 2003Google Scholar

3 Jeste DV, Blazer DG, First M: Aging-related diagnostic variations: need for diagnostic criteria appropriate for elderly psychiatric patients. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58: 265– 271Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Bair BD: Frequently missed diagnosis in geriatric psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1998; 21: 941– 971, viiiCrossref, Google Scholar

5 Unutzer J: Clinical practice: late-life depression. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 2269– 2277Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Amore M, Tagariello P, Laterza C, Savoia EM: Beyond nosography of depression in elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2007; 44: 13– 22Google Scholar

7 Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakuma T, Silbersweig D, Charlson M: Clinically defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 562– 565Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Shulman KI, Hermann N: Bipolar disorder in old age. Can Fam Physician 1999; 45: 1229– 1237Google Scholar

9 Gildengers AG, Butters MA, Seligman K, McShea M, Miller MD, Mulsant BH, Kupfer DJ, Reynold CF: Cognitive functioning in late-life bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 736– 738Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Young RC, Murphy CF, Heo M, Schulberg HC, Alexopoulos GS: Cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder in old age: literature review and findings in manic patients. J Affect Disord 2006; 92: 125– 131Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Palmer BW, Jeste DV, Sheikh JI: Anxiety disorders in the elderly: DSM-IV and other barriers to diagnosis and treatment. J Affect Disord 1997; 46: 183– 190Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JDJ, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45: 977– 986Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Flint AJ: Anxiety disorders in late life. Can Fam Physician 1999; 45: 2672– 2679Google Scholar

14 Creamer M, Parslow R: Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in the elderly: a community prevalence study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 16: 853– 856Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Cucchiara S, Latiano A, Palmieri O, Canani RB, D'Inca R, Guariso G, Vieni G, De Venuto D, Riegler G, De'Angelis GL, Guagnozzi D, Bascietto C, Miele E, Valvano MR, Bossa F, Annese V: Polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor-α but not MDR1 influence response to medical therapy in pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007; 44: 171– 179Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Vahia I, Bankole AO, Reyes P, Diwan S, Palekar N, Sapra M, Ramirez P, Cohen CI: Schizophrenia in later life. Aging Health 2007; 3: 383– 396Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Cohen CI, Vahia I, Reyes P, Diwan S, Bankole AO, Palekar N, Kehn M, Ramirez P: Focus on geriatric psychiatry: schizophrenia in later life: clinical symptoms and social well-being. Psychiatr Serv 2008; 59: 232– 234Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Howard R, Rabins PV, Seeman MV, Jeste DV, International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group: Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 172– 178Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Cervantes AN, Rabins PV, Slavney PR: Onset of schizophrenia at age 100. Psychosomatics 2006; 47: 356– 359Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Cohen CI, Pathak R, Ramirez PM, Vahia I: Outcome among community dwelling older adults with schizophrenia: results using five conceptual models. Community Ment Health J (in press)Google Scholar

21 Christensen H, Low LF, Anstey KJ: Prevalence, risk factors and treatment for substance abuse in older adults. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2006; 19: 587– 592Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Simons LA, Simons J, McCallum J, Friedlander Y: Impact of smoking, diabetes and hypertension on survival time in the elderly: the Dubbo Study. Med J Aust 2005; 182: 219– 222Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Steinberg MB, Akincigil A, Delnevo CD, Crystal S, Carson JL: Gender and age disparities for smoking-cessation treatment. Am J Prev Med 2006; 30: 405– 412Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Stevenson JS: Alcohol use, misuse, abuse, and dependence in later adulthood. Annu Rev Nurs Res 2005; 23: 245– 280Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Patterson TL, Jeste DV: The potential impact of the baby-boom generation on substance abuse among elderly persons. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50: 1184– 1188Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Berlau D, Paganini-Hill A, Kawas CH: Prevalence of dementia after age 90: results from the 90+ study. Neurology 2008; 71: 337– 343Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Christensen H: What cognitive changes can be expected with normal ageing? Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2001; 35: 768– 775Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Folstein MF, Whitehouse PJ: Cognitive impairment of Alzheimer disease. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 1983; 5: 631– 634Google Scholar

29 Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF: Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA 1993; 269: 2386– 2391Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Black SA, Espino DV, Mahurin R, Lichtenstein MJ, Hazuda HP, Fabrizio D, Ray LA, Markides KS: The influence of noncognitive factors on the Mini-Mental State Examination in older Mexican-Americans: findings from the Hispanic EPESE. Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52: 1095– 1102Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Wind AW, Schellevis FG, Van Staveren G, Scholten RP, Jonker C, Van Eijk JT: Limitations of the Mini-Mental State Examination in diagnosing dementia in general practice. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12: 101– 108Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M: The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51: 1451– 1454Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH III, Morley JE: Comparison of the Saint Louis University Mental Status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14: 900– 910Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 695– 699Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Levy JA, Chelune GJ: Cognitive-behavioral profiles of neurodegenerative dementias: beyond Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2007; 20: 227– 238Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H: Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 2006; 368: 387– 403Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, Patterson C, Cowan D, Levine M, Booker L, Oremus M: Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148: 379– 397Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, Paton J, Lyketsos CG: Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1996– 2021Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Ravaglia G, Forti P, Montesi F, Lucicesare A, Pisacane N, Rietti E, Dalmonte E, Bianchin M, Mecocci P: Mild cognitive impairment: epidemiology and dementia risk in an elderly Italian population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: 51– 58Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Feldman HH, Ferris S, Winblad B, Sfikas N, Mancione L, He Y, Tekin S, Burns A, Cummings J, Del Ser T, Inzitari D, Orgogozo JM, Sauer H, Scheltens P, Scarpini E, Herrmann N, Farlow M, Potkin S, Charles HC, Fox NC, Lane R: Effect of rivastigmine on delay to diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease from mild cognitive impairment: the InDDEx study. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 501– 512Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, Bennett D, Doody R, Ferris S, Galasko D, Jin S, Kaye J, Levey A, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, van Dyck CH, Thal LJ: Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2379– 2388Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Chertkow H, Massoud F, Nasreddine Z, Belleville S, Joanette Y, Bocti C, Drolet V, Kirk J, Freedman M, Bergman H: Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 3. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment without dementia. CMAJ 2008; 178: 1273– 1285Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Thomas AJ, O'Brien JT: Depression and cognition in older adults. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008; 21: 8– 13Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Mattis S, Kakuma T: The course of geriatric depression with “reversible dementia”: a controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150: 1693– 1699Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Camicioli R, Gauthier S: Clinical trials in Parkinson's disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Can J Neurol Sci 2007; 34 ( suppl 1): S109– S117Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Troster AI: Neuropsychological characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia: differentiation, early detection, and implications for “mild cognitive impairment” and biomarkers. Neuropsychol Rev 2008; 18: 103– 119Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Vale S: Current management of the cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: how far have we come? Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008; 233: 941– 951Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Janvin CC, Larsen JP, Salmon DP, Galasko D, Hugdahl K, Aarsland D: Cognitive profiles of individual patients with Parkinson's disease and dementia: Comparison with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Mov Disord 2006; 21: 337– 342Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Molloy SA, Rowan EN, O'Brien JT, McKeith IG, Wesnes K, Burn DJ: Effect of levodopa on cognitive function in Parkinson's disease with and without dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77: 1323– 1328Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Fenelon G: Psychosis in Parkinson's disease: phenomenology, frequency, risk factors, and current understanding of pathophysiologic mechanisms. CNS Spectr 2008; 13: 18– 25Google Scholar

51 Josephs KA: Frontotemporal dementia and related disorders: deciphering the enigma. Ann Neurol 2008; 64: 4– 14Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, Pasquier F: Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004; 17: 355– 359Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Duron E, Hanon O: Vascular risk factors, cognitive decline, and dementia. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008; 4: 363– 381Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Kavirajan H, Schneider LS: Efficacy and adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in vascular dementia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 782– 792Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Assal F, Cummings JL: Neuropsychiatric symptoms in the dementias. Curr Opin Neurol 2002; 15: 445– 450Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Jeste DV, Meeks TW, Kim DS, Zubenko GS: Research agenda for DSM-V: diagnostic categories and criteria for neuropsychiatric syndromes in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2006; 19: 160– 171Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Snitz BE, Bieliauskas LA, Crossland AR, Basso MR, Roper B: PPVT-R as an estimate of premorbid intelligence in older adults. Clin Neuropsychol 2000; 14: 181– 186Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Stone BJ, Gray JW, Dean RS, Wheeler TE: An examination of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) subtests from a neuropsychological perspective. Int J Neurosci 1988; 40: 31– 39Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Ashendorf L, Jefferson AL, Green RC, Stern RA: Test-retest stability on the WRAT-3 reading subtest in geriatric cognitive evaluations. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol (in press)Google Scholar

60 Fitzhugh KB, Fitzhugh LC, Reitan RM: Relation of acuteness of organic brain dysfunction to Trail Making Test performances. Percept Mot Skills 1962; 15: 399– 403Crossref, Google Scholar

61 LeFever FF: Relationships between the Digit Symbol test and a noncoding motoric equivalent in assessments of brain-damaged patients. Percept Mot Skills 1991; 72: 65– 66Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Hsieh PC, Chu CL, Yang YK, Yang YC, Yeh TL, Lee IH, Chen PS: Norms of performance of sustained attention among a community sample: Continuous Performance Test study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 59: 170– 176Crossref, Google Scholar

63 De Renzi E, Vignolo LA: The token test: a sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain 1962; 85: 665– 678Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Cauthen NR: Verbal fluency: normative data. J Clin Psychol 1978; 34: 126– 129Crossref, Google Scholar

65 LaBarge E, Edwards D, Knesevich JW: Performance of normal elderly on the Boston Naming Test. Brain Lang 1986; 27: 380– 384Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Tombaugh TN, Faulkner P, Hubley AM: Effects of age on the Rey-Osterrieth and Taylor complex figures: test-retest data using an intentional learning paradigm. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1992; 14: 647– 661Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Savage RM, Gouvier WD: Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test: the effects of age and gender, and norms for delayed recall and story recognition trials. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 1992; 7: 407– 414Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Delis DC, Freeland J, Kramer JH, Kaplan E: Integrating clinical assessment with cognitive neuroscience: construct validation of the California Verbal Learning Test. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56: 123– 130Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Baddeley A: Working memory and language: an overview. J Commun Disord 2003; 36: 189– 208Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Hanna-Pladdy B: Dysexecutive syndromes in neurologic disease. J Neurol Phys Ther 2007; 31: 119– 127Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Haaland KY, Vranes LF, Goodwin JS, Garry PJ: Wisconsin Card Sort Test performance in a healthy elderly population. J Gerontol 1987; 42: 345– 346Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Demakis GJ: Frontal lobe damage and tests of executive processing: a meta-analysis of the category test, Stroop test, and trail-making test. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2004; 26: 441– 450Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

74 Moye J, Marson DC: Assessment of decision-making capacity in older adults: an emerging area of practice and research. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007; 62: 3– 11Google Scholar

75 Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: The MacArthur Treatment CompetenceStudy. I: Mental illness and competence to consent to treatment. Law Hum Behav 1995; 19: 105– 126Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Kim SY, Karlawish JH, Caine ED: Current state of research on decision-making competence of cognitively impaired elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10: 151– 165Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: Assessing patients' capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 1988; 319: 1635– 1638Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Ensberg M, Gerstenlauer C: Incremental geriatric assessment. Prim Care 2005; 32: 619– 643Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Lawton MP, Brody EM: Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9: 179– 186Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA: The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J Gerontol 1981; 36: 428– 434Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Landi F, Onder G, Cesari M, Barillaro C, Russo A, Bernabei R: Psychotropic medications and risk for falls among community-dwelling frail older people: an observational study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60: 622– 626Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Podsiadlo D, Richardson S: The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39: 142– 148Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Inouye SK: Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1157– 1165Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT: Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007; 5: 345– 351Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Alexopoulos GS, Vrontou C, Kakuma T, Meyers BS, Young RC, Klausner E, Clarkin J: Disability in geriatric depression. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153: 877– 885Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Hull J, Sirey JA, Kakuma T: Clinical determinants of suicidal ideation and behavior in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56: 1048– 1053Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Bostwick JM: The many faces of confusion. Timing and collateral history often hold the key to diagnosis. Postgrad Med 2000; 108: 60– 66, 71Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Borja B, Borja CS, Gade S: Psychiatric emergencies in the geriatric population. Clin Geriatr Med 2007; 23: 391– 400, viiCrossref, Google Scholar

89 Coffernils M, De Rijcke A, Herbaut C: Hyperparathyroidism and depression: a clinical case and review of the literature. Rev Med Brux 1989; 10: 29– 32Google Scholar

90 Brenes GA: Anxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Psychosom Med 2003; 65: 963– 970Crossref, Google Scholar

91 Paulson GW: Visual hallucinations in the elderly. Gerontology 1997; 43: 255– 260Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Ancoli-Israel S, Ayalon L: Diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14: 95– 103Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Blazer DG: Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58: 249– 265Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Oslin DW: Late-life alcoholism: issues relevant to the geriatric psychiatrist. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004; 12: 571– 583Crossref, Google Scholar

95 Simoni-Wastila L, Yang HK: Psychoactive drug abuse in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006; 4: 380– 394Crossref, Google Scholar

96 Devlin RJ, Henry JA: Clinical review: major consequences of illicit drug consumption. Crit Care 2008; 12: 202Crossref, Google Scholar

97 Fink A, Hays RD, Moore AA, Beck JC: Alcohol-related problems in older persons: determinants, consequences, and screening. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156: 1150– 1156Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Reus VI: Behavioral disturbances associated with endocrine disorders. Annu Rev Med 1986; 37: 205– 214Crossref, Google Scholar

99 Roose SP: Depression, anxiety, and the cardiovascular system: the psychiatrist's perspective. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 ( suppl 8): 19– 22Crossref, Google Scholar

100 Newman S, Mulligan K: The psychology of rheumatic diseases. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2000; 14: 773– 786Crossref, Google Scholar

101 Lenze EJ, Karp JF, Mulsant BH, Blank S, Shear MK, Houck PR, Reynolds CF: Somatic symptoms in late-life anxiety: treatment issues. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2005; 18: 89– 96Crossref, Google Scholar

102 Meeks TW, Dunn LB, Kim DS, Golshan S, Sewell DD, Atkinson JH, Lebowitz BD: Chronic pain and depression among geriatric psychiatry inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 23: 637– 642Crossref, Google Scholar

103 Levy RH, Collins C: Risk and predictability of drug interactions in the elderly. Int Rev Neurobiol 2007; 81: 235– 251Crossref, Google Scholar

104 Bergman-Evans B: Evidence-based guideline. Improving medication management for older adult clients. J Gerontol Nurs 2006; 32: 6– 14Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Tune LE: Anticholinergic effects of medication in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 ( suppl 21): 11– 14Google Scholar

106 Marchetti GF, Whitney SL: Older adults and balance dysfunction. Neurol Clin 2005; 23: 785– 805, viiCrossref, Google Scholar

107 Colucci VJ, Berry BD: Heart failure worsening and exacerbation after venlafaxine and duloxetine therapy. Ann Pharmacother 2008; 42: 882– 887Crossref, Google Scholar

108 Kerr SR, Pearce MS, Brayne C, Davis RJ, Kenny RA: Carotid sinus hypersensitivity in asymptomatic older persons: implications for diagnosis of syncope and falls. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 515– 520Crossref, Google Scholar

109 Norman DC, Yoshikawa TT: Fever in the elderly. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1996; 10: 93– 99Crossref, Google Scholar

110 Caligiuri MR, Jeste DV, Lacro JP: Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and treatment recommendations. Drugs Aging 2000; 17: 363– 384Crossref, Google Scholar

111 Heisel MJ: Suicide and its prevention among older adults. Can J Psychiatry 2006; 51: 143– 154Crossref, Google Scholar

112 Davis JD, Tremont G: Neuropsychiatric aspects of hypothyroidism and treatment reversibility. Minerva Endocrinol 2007; 32: 49– 65Google Scholar

113 Kirby D, Ames D: Hyponatraemia and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in elderly patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16: 484– 493Crossref, Google Scholar

114 Mangoni AA, Jackson SH: Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 57: 6– 14Google Scholar

115 Yates WR, Gleason O: Hepatitis C and depression. Depress Anxiety 1998; 7: 188– 193Crossref, Google Scholar

116 Becker M, Axelrod DJ, Oyesanmi O, Markov DD, Kunkel EJ: Hematologic problems in psychosomatic medicine. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2007; 30: 739– 759Crossref, Google Scholar

117 Sernyak MJ: Implementation of monitoring and management guidelines for second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68 ( suppl 4): 14– 18Crossref, Google Scholar

118 Wilson MM: Sexually transmitted diseases in older adults. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2006; 8: 139– 147Crossref, Google Scholar

119 Manepalli J, Grossberg GT, Mueller C: Prevalence of delirium and urinary tract infection in a psychogeriatric unit. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1990; 3: 198– 202Crossref, Google Scholar

120 Mueller C, Rufer M, Moergeli H, Bridler R: Brain imaging in psychiatry—a study of 435 psychiatric in-patients at a university clinic. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006; 114: 91– 100Crossref, Google Scholar

121 Chong SA, Mythily, Mahendran R: Cardiac effects of psychotropic drugs. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2001; 30: 625– 631Google Scholar

122 Adamis D, Sahu S, Treloar A: The utility of EEG in dementia: a clinical perspective. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20: 1038– 1045Crossref, Google Scholar

123 Raedler TJ, Wiedemann K: CSF-studies in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2006; 27: 297– 305Google Scholar

124 Sempere AP, Callejo-Dominguez JM, Garcia-Clemente C, Ruiperez-Bastida MC, Mola-Caballero DR, Garcia-Barragan N, Vela-Yebra R, Flores-Ruiz JJ: Cost effectiveness of the diagnostic study of dementia in an extra-hospital neurology service. Rev Neurol 2004; 39: 807– 810Google Scholar

125 Small GW, Leiter F: Neuroimaging for diagnosis of dementia. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59 ( suppl 11): 4– 7Google Scholar

126 Nordberg A: Amyloid plaque imaging in vivo: current achievement and future prospects. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008; 35 ( suppl 1): S46– S50Crossref, Google Scholar

127 Coleman RE: Positron emission tomography diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2005; 15: 837– 846, xCrossref, Google Scholar

128 Van Etten D: Psychotherapy with older adults: benefits and barriers. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2006; 44: 28– 33Google Scholar

129 Schumacher K, Beck CA, Marren JM: FAMILY CAREGIVERS: caring for older adults, working with their families. Am J Nurs 2006; 106: 40– 49Google Scholar

130 Zisook S, Paulus M, Shuchter SR, Judd LL: The many faces of depression following spousal bereavement. J Affect Disord 1997; 45: 85– 94Crossref, Google Scholar

131 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, Biometrics Research, N.Y. State Psychiatric Institute, 2002Google Scholar

132 Wheelock I: Psychodynamic psychotherapy with the older adult: challenges facing the patient and the therapist. Am J Psychother 1997; 51: 431– 444Crossref, Google Scholar

133 Soares JJ, Macassa G, Grossi G, Viitasara E: Psychosocial correlates of hopelessness among men. Cogn Behav Ther 2008; 37: 50– 61Crossref, Google Scholar

134 Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR: Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000; 79: 644– 655Crossref, Google Scholar

135 Le TN: Cultural values, life experiences, and wisdom. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2008; 66: 259– 281Crossref, Google Scholar

136 Mookadam F, Arthur HM: Social support and its relationship to morbidity and mortality after acute myocardial infarction: systematic overview. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 1514– 1518Crossref, Google Scholar

137 Lyness JM, Chapman BP, McGriff J, Drayer R, Duberstein PR: One-year outcomes of minor and subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients. Int Psychogeriatr 2009; 21: 60– 68Crossref, Google Scholar

138 Swanson E: Culturally competent care for older adults: we are making progress. J Gerontol Nurs 2006; 32: 4Google Scholar