Depression, Pain, and Aging

Abstract

The prevalence of persistent pain increases with age. Painful conditions such as fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, osteoarthritis, and neuropathic pain are frequently comorbid with depression. When comorbid, these conditions slow the treatment of each other, worsen physical and psychological disability, and increase caregiving burden. Anatomic, neurochemical, and psychological similarities lead to high rates of comorbidity. Anxiety, disordered sleep, fatigue, and cognitive impairment are frequent “cotravelers” with depression and pain in late life; these conditions require vigilant screening and treatment. Psychiatrists should be familiar with current analgesic prescribing patterns and be able to effectively collaborate with primary care physicians and physical therapists to optimize treatment outcomes for patients with these complex problems. In this article we provide a review of the literature, an update on some of our own research in this area, and relevant clinical perspectives.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DEPRESSION AND PAIN IN LATE LIFE

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common in older adults, with a 1-year prevalence of 6%–10% in primary care settings (1). Depressive symptoms that cause distress and interfere with day-to-day functioning occur in approximately 15% of community-dwelling older adults (1). MDD amplifies disability, hastens cognitive and functional decline, increases risk of hospitalization, diminishes quality of life, and burdens caregivers. Perhaps of gravest concern is the increase in mortality from both associated medical comorbidity and suicide (2). Partially treated MDD usually follows a relapsing, recurrent course (3). Comorbid medical conditions such as persistent pain are linked to poor treatment response and poor long-term outcomes in late-life depression (4–6).

As the population of developed countries ages, there has been an increase in the prevalence of conditions associated with persistent pain across settings of care (7). Indeed, both the incidence and the prevalence of pain that interferes with life increase sharply with age (9, 9). In the United States and Canada, 25%–50% of community-dwelling older adults and 49%–83% of nursing home residents report pain (10–13). Data from Europe echo these prevalence estimates (14–17). The prevalence of persistently painful conditions among older adults is particularly noteworthy in light of their association with functional impairment, sleep disturbance, depression and anxiety, and decreased socialization (18). As people age, living with a painful condition becomes the norm, rather than the exception.

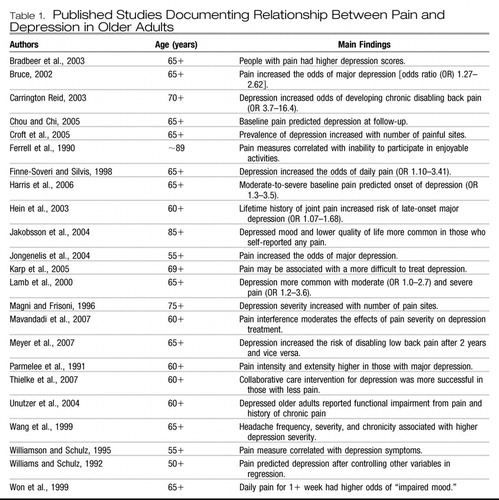

The association between depression and pain in older adults has been demonstrated consistently (19–23) (Table 1). Depression and pain are mutually exacerbating and disabling: MDD and pain are risk factors for the onset of each other and when comorbid slow treatment outcomes for each other (5, 24–28). Persistent pain increases the risk of becoming depressed, worsens the depression experience, decreases quality of life, and lengthens time to remission of depression (4, 5). The relationship between depression and pain is strongly influenced by physical disability: persistent pain conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA), low back pain, neuropathic pain, and fibromyalgia often lead to physical disability, which in turn contributes to symptoms of depression (23, 29).

|

Table 1. Published Studies Documenting Relationship Between Pain and Depression in Older Adults

We have shown that 1) in mixed age adults, the presence of pain slows depression response to antidepressant pharmacotherapy and 2) in older adults, pain may predict more difficult-to-treat depression (4, 5). Other groups have also demonstrated this relationship in older populations (27, 28). Carrington Reid reported that the presence of depressive symptoms was a strong, independent, and highly prevalent risk factor for the occurrence of disabling back pain in community-dwelling older persons (26). A large epidemiologic study of back pain in older adults also found that symptoms of depression were more common among individuals with back pain than among those without pain (30). Another recent large-scale study showed that the variables significantly associated with the development of pain interference were 1) being older, 2) having pain in more than one site, 3) depression, 4) anxiety, 5) smoking, and 6) obesity (31).

BIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL LINKS

It has been repeatedly observed that depression and persistent pain are both 1) dynamic conditions with waxing and waning symptoms, 2) exacerbated by environmental stressors, and 3) often responsive to similar pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments. Potential explanations for these similarities include 1) congruent psychological profiles between patients with mood disorders and those with persistent pain conditions (32, 33) and 2) similar brain regions involved in both depression and pain (e.g., dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, periaqueductal gray, insula cortex, and hypothalamus) (34–36).

PSYCHOLOGICAL SIMILARITIES

Self-efficacy and learned helplessness are relevant psychological theories for conceptualizing depression and persistent pain in late life: The literature suggests that diminished self-efficacy (the belief that one is capable of obtaining certain goals such as depression or pain relief) is strongly associated with both depressive illness episodes (37) and chronic pain (38, 39) in late life. Self-efficacy (40) reflects a person's belief that his or her efforts to perform certain tasks will be successful: “I can do this!” The absence of self-efficacy is reflected in learned helplessness (41), which refers to a constellation of behavioral changes that follow exposure to stressors such as depression or chronic pain that are not controllable by means of behavioral responses but that fail to occur if the stressor is controllable (42).

Many older adults who become disabled as a result of either MDD or persistent pain have a reduced sense of being able to manage these chronic stressors. For example, depression and low personal mastery (the sense of personal control over health outcomes) have been shown to be significantly associated with frequent back pain (30).

BIOLOGICAL SIMILARITIES

Pain processing in the brain occurs via the spinothalamic tracts and in multiple deep brain and cerebral areas. Thalamic relays to hypothalamic and limbic systems pass further upstream to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, insula, posterior parietal complex, somatosensory cortex, and supplementary motor cortex (43).

The emotional response to pain involves the ascending reticular activating system, which sends fibers to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, limbic system, hypothalamus, cerebellum, and dorsal horn of the spinal cord (44). Anatomically the pain-processing areas of the brain include the same areas seen in mood and anxiety disorders (43, 45).

The pathophysiology of both mild age-related changes and more severe changes associated with dementia is neuronal death and gliosis. Areas of the brain involved with pain perception, analgesia, and mood are susceptible to these pathological changes. Functionally, neuronal death and gliosis may directly interrupt the neuronal tracts involved in descending inhibition of pain and mood control, especially those involved with the periaqueductal gray, locus coeruleus, and nucleus raphe magnus, areas rich in opioid and monoamine receptors (17, 46). In addition, there is evidence that compared with normal control subjects, patients with chronic pain have a reduction in neocortical gray matter; in a study of patients with chronic back pain, the loss of prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density was equivalent to that lost in 10–20 years of normal aging (47). More recent work suggests that older adults with chronic low back pain (CLBP) have structural brain changes in the middle corpus callosum, the middle cingulate cortex, and the posterior parietal cortex (48). These brain changes may have relevance for both analgesia and mood regulation.

DISABILITY: A CRITICAL LINK BETWEEN DEPRESSION AND PAIN

“Disability” is the result of body function impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions, consistent with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (49, 50). These deficits are a critical dimension of depression (51) and are frequently encountered in patients living with chronic pain. For many older adults, these limitations may be more profound than the core symptoms of depression or anxiety (e.g., sadness, anhedonia, or nervousness) or pain intensity. Changes in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living include reports of difficulty performing 1) personal care, 2) meal preparation, 3) shopping and financial management, 4) housework, 5) familial or volunteer activities, or 6) organized social activities (52–54).

Decrements in health status associated with painful conditions such as OA, fibromyalgia, postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), low back pain, and diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain can lead to functional limitations (i.e., restrictions in basic actions such as walking, climbing stairs, dressing, reaching, and gripping). These functional limitations, in turn, may lead to disability. Thus, as described above, disability is defined as difficulty in activities, inability to perform activities, or restriction in or relinquishment of activities (55).

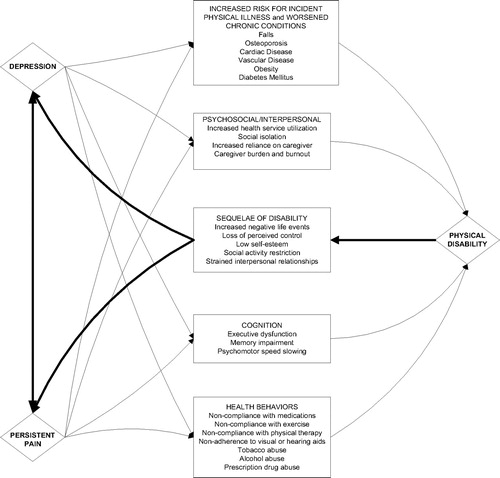

For example, in a study of older adults with knee OA, at baseline the relationships of depression with functional disability and activity limitation were wholly mediated by pain (56). One-year follow-up revealed that depressive symptoms increased with increasing health problems and with reduction in activity participation over time. Having and retaining favorite pastimes were also associated with reduced depressive symptomatology at baseline and follow-up, respectively. These data highlight the disease-specific nature of paths among depression, pain, and disability and the importance of considering discretionary as well as necessary activities in evaluating effects of pain upon quality of life and depression in particular. Readers are referred to the thorough review of Lenze et al. (57) about late-life depression and disability. In their synthesis of the literature, Lenze et al. observed that 1) depression is a risk factor for disability (58–60), 2) disability (including from pain) is a risk factor for depression (61–63), and 3) when depression and disability occur simultaneously (61, 64–66), either both worsen, both remain constant, or both improve, suggesting a “synchrony of change” between depression and disability, which has also been described in younger-aged populations (67). Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between depression, pain, and disability in older adults.

Figure 1. Relationships Among Depression, Pain, and Physical Disability in Older Adults.

DO ALL OLDER PAIN PATIENTS HAVE DEPRESSION?

Results from a comparison of patients with knee and back pain show that knee OA and CLBP are common among older adults. To help with treatment planning, we were interested in which condition had higher rates of psychological impairments. We compared the psychological profiles of older adults with CLBP versus older adults with chronic knee OA (68). The sample consisted of 200 older adults with CLBP and 88 older adults with advanced knee OA who had participated in separate randomized clinical trials. Inclusion criteria for both trials were age 65 years and older and pain of at least moderate intensity that occurred daily or almost every day for at least the previous 3 months. The psychological constructs we assessed were depression, affective distress, catastrophizing, fear avoidance, and self-efficacy. Except for the Multidimensional Pain Inventory–Affective Distress score, all of the psychological measures were significantly worse in the CLBP group. These findings suggest that clinicians should have increased vigilance for comorbid emotional distress in older adults living with CLBP.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

ASSESSING COMORBIDITY

To optimize both analgesia and mood outcomes for older adults living with both pain and depression, comorbid conditions affecting quality of life should be screened for, accurately diagnosed, and treated. The neuropsychiatric conditions we observe most frequently include nonrestorative sleep, fatigue, anxiety, and cognitive impairment.

COMORBID SLEEP DISORDERS

Sleep disorders and persistent pain mutually interact, and it is often a clinical challenge to determine whether exacerbations in pain are due to poor sleep quality or whether sleep disturbance is due to nocturnal pain. For example, sleep deprivation can trigger a decrease in pain tolerance and pain thresholds (69). Conversely, chronic pain may lead to nonrestorative sleep and sleep fragmentation (70). Similarly, depression is associated with sleep continuity disturbance, early morning awakening (both related to nonrestorative sleep), and daytime fatigue. Finally, relative to that of the young, the sleep of older adults is characterized by more frequent intrasleep arousals. This fractured sleep is more likely to be rated as poor in quality. The sleep of older adults is also structurally lighter, as is evidenced by a diminution of deeper slow wave sleep and a reciprocal increase in stages 2 (light sleep) and 1 (drowsiness). In summary, aging, pain, depression, and sleep are all linked.

COMORBID ANXIETY

Anxiety is a frequent cotraveler with depression and pain, especially among primary care patients (71). A thought process central to many anxious patients is “What if ?” Among older patients with chronic pain, these “what if” thoughts are frequently about 1) worsening pain, 2) disability, 3) death, and 4) opioid dependence. For example, abdominal pain, perhaps due to chronic opioid-induced or age-related constipation, may be perceived as indicative of a potentially serious condition such as colon cancer (“What if my belly pain means I have cancer?”) and becomes a focus of constant worry, thereby increasing the sensation of gastrointestinal distress and pain. Patients who are worried that exercise or other movement (“What if I cause more pain with activity?”) will cause damage to an already sore back or hip (perhaps despite medical advice to stay active) may become deconditioned and actually make their pain—and ultimately their anxiety—worse. Because of the increased rate of comorbid medical problems that often lead to increased focus on disease, the worry surrounding somatic preoccupation is of particular relevance for anxious older adults.

At least two studies have provided support for the pain and anxiety link in older adults. One of these is the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, a prospective multidisciplinary research study of normative aging (N = 374). These researchers found that women reporting knee pain in the absence of radiographic OA had higher anxiety scores than those without pain. Depression was not significantly related to knee pain in this population (72). In another study of nursing home residents, pain intensity and number of pain complaints were assessed. A series of path models indicated that 1) both research-based anxiety and depression share unique variance with pain and 2) only the Profile of Mood States (73) anxiety scale was uniquely related to pain (74). These studies suggest that pain and anxiety assessment should be conducted simultaneously as they frequently copresent.

COMORBID COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Alzheimer disease is the most common dementing illness among older adults, affecting an estimated 8%–15% of individuals age 65 years and older. Older adults with dementia may have exaggerated fear avoidance and catastrophize excessively when faced with pain. Impaired coping in these patients may be the primary driver of disability rather than pain severity. Even in older patients with pain who do not have dementia, we have observed associations between pain severity and impairments in memory, executive functioning, and information processing speed (75, 76). In our clinical work with this population, we have noted that some cognitively impaired older adults complain of chronic ill-defined pain that is not concordant with their affective state (i.e., they perseverate about the pain but do not appear to be distressed when describing it and actually seem to emotionally benefit from the attention). These patients may actually be communicating emotional distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, or loneliness) instead of pain severity or pain unpleasantness.

CRAFTING A TREATMENT PLAN

We use a collaborative, patient-centered approach when developing a treatment plan for older adults living with comorbid depression and chronic pain. Severity of depression and type of pain (localized versus widespread or diffuse pain) are two of the primary variables that guide treatment planning. Patients with mild depression and localized pain (e.g., knee OA) often have improvements in mood, pain, and functioning with attention to behavioral medicine recommendations (such as diet and exercise), which have effects on both 1) improving self-efficacy (77) and 2) reducing disability (78). For example, assistance with weight loss and encouragement to exercise (79, 80), delivered in a supportive/behavioral intervention such as problem-solving therapy (81, 82), has been shown to be efficacious in improving mood and disability. In our psychiatric practice, we routinely refer patients to and collaborate with colleagues in physical therapy. Physical therapy often improves depression (83). Our primary care colleagues appreciate the attention that we pay to the psychological, analgesic, and physical health of their patients.

Analgesics can improve the mild depression associated with pain and disability. Probably the mechanism of action of analgesics is not as conventional antidepressants (i.e., via the traditional monoamine hypothesis), but rather by improving mobility and independence, decreasing pain, and improving sleep. For two excellent reviews of the treatment of older adults with chronic pain, readers are referred to a report by the American Geriatrics Society, “The Management of Chronic Pain in Older Persons” (18), and an article by Weiner, “Office Management of Chronic Pain in the Elderly” (84).

Patients with depression and widespread pain often require an approach different from that for those with depression and localized pain. The most common cause of diffuse widespread pain in older adults is fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS). As with other types of musculoskeletal pain, FMS increases in prevalence with age and affects 7% of women aged 60 to 79 (85). The criteria used for FMS include a history of generalized body pain (i.e., pain in at least 3 of 4 body quadrants) for at least 3 months duration and at least 11 of 18 specific tender points on physical examination (86). Even if patients do not have at least 11 tender points, but the clinical picture suggests FMS (i.e., in addition to pain, patients report stiffness, fatigue, headache, cognitive impairment, poor sleep, irregular gastrointestinal and urinary functioning, depression, and anxiety), we generally apply either the diagnosis of FMS or the DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of “Pain Disorder Associated with Both Psychological Factors and a General Medical Condition” and initiate treatment.

Despite an increase in research on FMS, its pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recent data indicate that patients with FMS have enhanced sensitivity to multiple types of sensory stimuli (87). Most experts agree that central sensitization plays a key role in FMS symptoms. Central sensitization suggests a heightened response of the central nervous system to nonpainful stimuli (allodynia) and painful stimuli (hyperalgesia). It is common for multiple central sensitization syndromes including FMS, headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and restless leg syndrome to present as comorbid conditions. Depression is comorbid with FMS in up to 34.8% of patients (16) and frequently presents with these other central sensitization conditions. Thus, these conditions may be viewed as an affective/pain central sensitization syndrome. This makes sense, as 1) there is overlap in the brain regions implicated in these conditions and 2) the treatments for these conditions are often the same (e.g., antidepressants and cognitive behavior therapy).

When less common causes of widespread pain in older adults are ruled out (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, or polymyalgia rheumatica) and patients are also depressed, treatment with both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition is indicated. In a study comparing 20 mg/day fluoxetine and 20 mg/day amitriptyline with placebo in a randomized, double-blind, crossover study, Goldenberg et al. (88) reported that patients receiving both fluoxetine and amitriptyline had improvement in pain, global well-being, and sleep disturbance scores. The combination of fluoxetine and amitriptyline was more effective than either alone. We do not recommend the routine use of either of these medications for older adults because of the long half-life of fluoxetine and the anticholinergic and cardiac effects of amitriptyline. Another double-blind placebo-controlled study using citalopram for FMS showed no improvement in pain scores or global functioning with the active agent (89). Milnacipran is a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, available only in Europe and Asia, that reduces pain and fatigue and improves overall well-being in patients with FMS (90). Esreboxetine, a highly selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is currently being evaluated as a treatment for FMS. Given its noradrenergic properties, it will probably have antidepressant and antianxiety properties as well.

Currently, the only serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is indicated for the treatment of both MDD and FMS is duloxetine. For both MDD and FMS, the recommended dose of duloxetine is 60 mg/day. We have found that patients with comorbid FMS and MDD often require and tolerate 90–120 mg/day.

Although venlafaxine is not indicated for the treatment of any pain conditions, there are reports that it may improve pain and functioning for patients with fibromyalgia (91), painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy (92), and chronic pain with associated MDD (93). O-Desmethylvenlafaxine, the primary metabolite of venlafaxine, is present in the highest steady-state plasma levels and is the most potent inhibitor of both noradrenaline and serotonin reuptake. This finding is relevant because the reuptake of norepinephrine by venlafaxine, the neurotransmitter with documented analgesic properties (94, 95), is probably not inhibited at lower doses. For example, relating in vitro reuptake inhibitory concentrations to steady-state plasma concentrations suggests that serotonin reuptake inhibition will be maximal at low doses (<100 mg/day), whereas noradrenaline reuptake can be expected to increase over the dose range from 100 to 400 mg/day (96). Thus, to achieve noradrenergic blockade with its theoretical greater analgesic effect, venlafaxine doses of at least 100 mg/day are required. Our group has shown that older adults with major depression tolerate doses at least up to 300 mg/day (97).

Our experience has been to initiate treatment with duloxetine at 30 mg/day or venlafaxine at 37.5 mg/day to reduce the risk of treatment-emergent side effects such as gastrointestinal distress and anxiety. Patients with affective/pain central sensitization syndromes are often exquisitely sensitive to side effects and are quick to discontinue a medication before an adequate trial has been completed. Providing education about side effects so patients are not “taken by surprise” often improves compliance and reduces early medication discontinuation. Discussions with depressed or anxious patients living with chronic widespread pain such as FMS often include a variation of the following: “This medication is an antidepressant that should help your pain, mood, (and/or anxiety). Sometimes people experience an upset stomach, headaches, increased anxiety, and sweating. We'll start this medication at a low dose and increase it slowly to avoid these annoying but not dangerous side effects. If you can stick with taking the medication every day and let me help you manage any of these side effects that should go away by themselves in less than a week, there is a good chance that this medication may help you.”

PHARMACOLOGIC ALTERNATIVES TO ANTIDEPRESSANTS FOR OLDER ADULTS WITH DEPRESSION AND PAIN

Creative treatment planning is often required for older patients living with both depression and chronic pain. As stated above, many of these patients are exquisitely sensitive to medication side effects and are reluctant to try another antidepressant that they feel may have been associated with side effects such as gastrointestinal distress, diaphoresis, akathisia, anxiety, or headache. Although not indicated for the treatment of major depression, trials of anticonvulsant medications and antianxiety agents may improve both mood and pain. For example, valproate, topiramate, and carbamazepine all have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications for the treatment and/or prophylaxis of painful conditions (e.g., migraine or trigeminal neuralgia). These agents have also been observed to improve anxiety (98–100). We focus on three medications (gabapentin, pregabalin, and clonazepam) that may improve comorbid chronic pain, depression, and anxiety.

Gabapentin, a calcium channel modulator, has been shown to improve anxiety symptoms (101) associated with generalized anxiety disorder (102), panic disorder (103), and social phobia (104). In patients with epilepsy, gabapentin has been reported to improve depression (105). In our own work with older adults living with postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), fibromyalgia, myofascial pain syndromes, and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy and receiving treatment with gabapentin, we have often observed an improvement in mood, anxiety symptoms, and preoccupation with pain that occur simultaneously with analgesia. Although the only FDA-approved pain indication of gabapentin is the treatment of PHN, pregabalin, a medication with a similar molecular structure, is indicated for the treatment of PHN, fibromyalgia, and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Thus, if patients present with a predominantly anxious phenotype and are wary of trying (or trying again) an antidepressant, the use of gabapentin or pregabalin may be a rational choice. To minimize the risks of sedation, lightheadedness, and orthostasis (all of which increase the risk of falls), we increase the dose of these medications slowly in older adults. For gabapentin, we recommend starting at 100 mg/night and increasing by 100 mg/week. We try to get the dose to at least 900 mg/day (if tolerated). For pregabalin, we usually start at 25 mg/night and increase the dose by 25 mg/week to a target of 150–300 mg/day.

In addition to seizure prophylaxis, clonazepam is indicated for the treatment of panic disorder. The decision to use a benzodiazepine in older adults always must be weighed with the increased potential for 1) falls (106) 2) cognitive impairment (107), and 3) occult or diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (108, 109). In addition, potential diversion of controlled substances must be considered for patients of all ages. Although clonazepam has a relatively long half-life, it is not included on the Beer's list of potentially inappropriate medications for use in older adults (110). With these caveats, we have found that for some older patients living with chronic pain who have comorbid anxiety and depression, parsimonious use of clonazepam can greatly improve the quality of their lives. In particular, we have observed that older patients with myofascial pain syndromes and fibromyalgia, two conditions frequently comorbid with anxiety and depression (111–113), may note improvement in both pain and anxiety/depression when treated with clonazepam. We recommend use of the lowest therapeutic doses of benzodiazepines in all patients, but especially in older adults, to minimize the risks described above. For clonazepam, we often start with 0.5 mg/day and increase the dose to 1.5–2 mg/day as needed.

Although pharmacotherapy is almost always indicated for patients living with comorbid depression and widespread pain, there is evidence that disease education (114), exercise (115), multidisciplinary pain treatment programs (116), and cognitive behavior therapy (117) improve pain, depression, and quality of life.

COMMENT ABOUT OPIOID USE IN OLDER ADULTS WITH DEPRESSION AND PAIN

Depressed older adults living with chronic pain frequently have substandard pain management. For example, in a sample of 1,801 older primary care patients, Unutzer et al. (118) found that 79% reported functional impairment from pain within the previous month and 57% reported a diagnosis of or treatment for chronic pain within the past 3 years. However, almost half of the sample with functional impairment from pain did not report using analgesic medications. Opioid use varied from 5% to 34% of the sample. Predictors of analgesic use in these depressed elderly patients included a history of chronic pain or arthritis and the degree of functional impairment from chronic pain within the past month.

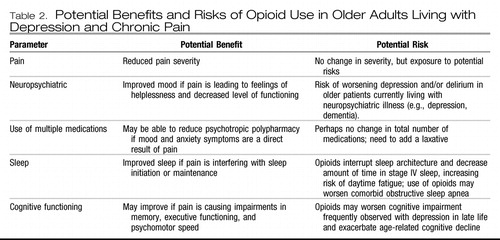

The decision to prescribe an opioid analgesic for an older adult, especially one with depression, always involves a risk-benefit analysis. Potential benefits include decreased pain, improved mobility, and improved cognition. Potential risks of opioid use in older adults, especially those with depression, are a worsening of depression, increased risk of falls, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, impaired cognition, delirium, polypharmacy, constipation, daytime fatigue, medication diversion, and changes in sleep architecture (i.e., less slow wave sleep). Table 2 lists the pros and cons that should be evaluated in the decision to prescribe an opioid analgesic for an older adult living with comorbid pain and depression.

|

Table 2. Potential Benefits and Risks of Opioid Use in Older Adults Living with Depression and Chronic Pain

If the decision is made to initiate treatment with opioids, careful monitoring is critical for both optimizing treatment and assuring safety. The accumulation of metabolites (because of age-related changes in pharmacokinetics) or a direct depressogenic effect of the opioid agent may occur. In addition to potential confusion and delirium, clinicians should monitor for change in depressive symptoms—either worsening or improvement.

Frequent assessment for an appropriate stop date and a plan to terminate therapy with the opioid when it is no longer needed should be in place from the beginning of treatment. For the opioid-naive patient, treatment should be initiated with a low-dose short-acting agent. The choice of potential opioid agents to be used in older adults living with chronic pain and depression who may benefit from treatment with an opioid analgesic is too complex to be covered in this article; readers are referred to the clinical practice guideline published by the American Geriatric Society entitled “The Management of Chronic Pain in Older Persons” (18).

CONCLUSION

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, by 2030, older adults will account for 20% of the total population—up from 13% in 2000. Within this cohort, persons 85 years and older comprise the most rapidly growing segment of the U.S. population. Nearly 20% of those who are 55 years and older experience mental disorders that are not part of normal aging. The most common conditions include depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment. Chronic pain conditions increase in prevalence with age, and 50% of older adults live with pain that interferes with daily activities. Depression and pain 1) are risk factors for each other, 2) are mutually exacerbating, and 3) interfere with effective treatment of each other.

In preparation for the wave of aging baby boomers, psychiatrists need to 1) understand the epidemiology and biology of comorbid depression and pain, 2) screen for the highly prevalent comorbidities such as disordered sleep, anxiety, and cognitive impairment, 3) know how to appropriately use analgesic medications, and 4) maintain an ongoing dialogue with our primary care and physical therapy colleagues to assure the best outcomes for these patients with complex problems.

1 Mulsant B, Ganguli M: Epidemiology and diagnosis of depression in late life. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60 ( Suppl 20): 9– 15Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Charney DS, Reynolds CF 3rd, Lewis L, Lebowitz BD, Sunderland T, Alexopoulos GS, Blazer DG, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Arean PA, Borson S, Brown C, Bruce ML, Callahan CM, Charlson ME, Conwell Y, Cuthbert BN, Devanand DP, Gibson MJ, Gottlieb GL, Krishnan KR, Laden SK, Lyketsos CG, Mulsant BH, Niederehe G, Olin JT, Oslin DW, Pearson J, Persky T, Pollock BG, Raetzman S, Reynolds M, Salzman C, Schulz R, Schwenk TL, Scolnick E, Unutzer J, Weissman MM, Young RC; Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance: Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Arch Gen Psychiatry Archives of General Psychiatry 2003; 60: 664– 672Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Zis AP, Goodwin FK: Major affective disorder as a recurrent illness: a critical review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36(8 Spec No): 835– 839Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Karp JF, Scott J, Houck P, Reynolds CF, Kupfer DJ, Frank E: Pain slows antidepressant treatment response. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 591– 597Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Karp JF, Weiner D, Seligman K, Butters M, Miller M, Frank E, Stack J, Mulsant BH, Pollock B, Dew MA, Kupfer DJ, Reynolds DF 3rd: Body pain and treatment response in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 13: 188– 194Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Reynolds CF 3rd, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Frank E, Miller MD, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Butters MA, Stack JA, Schlernitzauer MA, Whyte EM, Gildengers A, Karp J, Lenze E, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kupfer DJ: Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1130– 1138Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Desai MM, Zhang P, Hennessy CH: Surveillance for morbidity and mortality among older adults—United States, 1995–1996. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 1999; 48: 7– 25Google Scholar

8 Thomas E, Mottram S, Peat G, Wilkie R, Croft P: The effect of age on the onset of pain interference in a general population of older adults: prospective findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain 2007; 129: 21– 27Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, Wilkie R, Croft PR: The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain 2004; 110: 361– 368Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Crook J, Rideout E, Browne G: The prevalence of pain complaints in a general population. Pain 1984; 18: 299– 314Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Ferrell BA: Pain evaluation and management in the nursing home. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123: 681– 687Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Fox PL, Raina P, Jadad AR: Prevalence and treatment of pain in older adults in nursing homes and other long-term care institutions: a systematic review. CMAJ 1999; 160: 329– 333Google Scholar

13 Scudds RJ, Ostbye T: Pain and pain-related interference with function in older Canadians: the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Disabil Rehabil 2001; 23: 654– 664Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Donald IP, Foy C: A longitudinal study of joint pain in older people. Rheumatology 2004; 43: 1256– 1260Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Soldato M, Liperoti R, Landi F, Finne-Sovery H, Carpenter I, Fialova D, Bernabei R, Onder G: Non malignant daily pain and risk of disability among older adults in home care in Europe. Pain 2007; 129: 304– 310Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Thieme K, Turk DC, Flor H: Comorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychosocial variables. Psychosom Med 2004; 66: 837– 844Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Zarit SH, Griffiths PC, Berg S: Pain perceptions of the oldest old: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 2004; 44: 459– 468Crossref, Google Scholar

18 AGS Panel on Chronic Pain in Older Persons: The management of chronic pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: S205– S224Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Cook NR, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Scherr PA, Ostfeld AM, Taylor JO, Hennekens CH: Correlates of headache in a population-based cohort of elderly. Arch Neurol 1989; 46: 1338– 1344Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Moss MS, Lawton MP, Glicksman A: The role of pain in the last year of life of older persons. J Gerontol 1991; 46: P51– P57Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP: The relation of pain to depression among institutionalized aged. J Gerontol 1991; 46: P15– P21Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS: Pain and depression in the nursing home: corroborating results. J Gerontol 1993; 48: P96– P97Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Williamson GM, Schulz R: Pain, activity restriction, and symptoms of depression among community-residing elderly adults. J Gerontol 1992; 47: P367– P372Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, Stang PE, Croghan TW, Kroenke KM. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosom Med 2004; 66: 17– 22Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Reid MC, Otis J, Barry LC, Kerns RD: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain in older persons: a preliminary study. Pain Med 2003; 4: 223– 230Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Carrington Reid M, Williams CS, Concato J, Tinetti ME, Gill TM: Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for disabling back pain in community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51: 1710– 1717Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Mavandadi S, Ten Have TR, Katz IR, Durai UN, Krahn DD, Llorente MD, Kicehner JE, Olsen EJ, Van Stone WW, Cooley SL, Oslin DW: Effect of depression treatment on depressive symptoms in older adulthood: the moderating role of pain. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 202– 211Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Thielke S, Fan M, Sullivan M, Unutzer J: Pain limits the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 15: 699– 707Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Williamson GM, Schulz R: Activity restriction mediates the association between pain and depressed affect: a study of younger and older adult cancer patients. Psychol Aging 1995; 10: 369– 378Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Cecchi F, Debolini P, Lova RM, Macchi C, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Lauretani F, Benvenuti E, Hicks G, Ferrucci L: Epidemiology of back pain in a representative cohort of Italian persons 65 years of age and older: the InCHIANTI study. Spine 2006; 31: 1149– 1155Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G, Wilkie R, Croft P: Social risks for disabling pain in older people: a prospective study of individual and area characteristics. Pain 2008; 137: 652– 661Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Mayer TG, Garcy PD: Psychopathology and the rehabilitation of patients with chronic low back pain disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994; 75: 666– 670Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Gatchel R: Psychological disorders and chronic pain: cause and effect relationships, in Psychological Approaches to Pain Management: a Practitioner' S Handbook. Edited by Gatchel RJ, Turk DC. New York, Guilford, 1996Google Scholar

34 Hadjipavlou G, Dunckley P, Behrens TE, Tracey I: Determining anatomical connectivities between cortical and brainstem pain processing regions in humans: a diffusion tensor imaging study in healthy controls. Pain 2006; 123: 169– 178Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Aziz Q, Thompson DG, Ng VW, Hamdy S, Sarkar S, Brammer MJ, Bullmore ET, Hobson A, Tracey I, Gregory L, Simmons A, Williams SC: Cortical processing of human somatic and visceral sensation. J Neurosci 2000; 20: 2657– 2663Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Tracey I, Mantyh PW: The cerebral signature for pain perception and its modulation. Neuron 2007; 55: 377– 391Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Blazer DG: Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58: 249– 265Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Barry LC, Guo Z, Kerns RD, Duong BD, Reid MC: Functional self-efficacy and pain-related disability among older veterans with chronic pain in a primary care setting. Pain 2003; 104: 131– 137Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Rudy TE, Weiner DK, Lieber SJ, Slaboda J, Boston JR: The impact of chronic low back pain on older adults: a comparative study of patients and controls. Pain 2007; 131: 293– 301Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Rowe JW, Kahn RL: Successful aging. Aging (Milano) 1998; 10: 142– 144Google Scholar

41 Seligman ME: Learned helplessness. Annu Rev Med 1972; 23: 407– 412Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Maier SF, Watkins LR: Stressor controllability and learned helplessness: the roles of the dorsal raphe nucleus, serotonin, and corticotropin-releasing factor. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005; 29: 829– 841Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Moskowitz M, Fishman S: The neurobiological and therapeutic intersection of pain and affective disorders. Focus 2006; IV: 465– 471Google Scholar

44 Siegal G, Agranoff B, Albers R, Fisher S, Uhler M: Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects, 6th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999, pp 308– 309Google Scholar

45 Yaksh T. Anatomy of the pain processing system, in International Pain Management, 2nd ed. Edited by Waldman S. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2001, pp 11– 20Google Scholar

46 Zhuo M, Gebhart GF: Spinal cholinergic and monoaminergic receptors mediate descending inhibition from the nuclei reticularis gigantocellularis and gigantocellularis pars alpha in the rat. Brain Res 1990; 535: 67– 78Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Apkarian AV, Sosa Y, Sonty S, Levy RM, Harden RN, Parrish TB, Gitelman DR: Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 10410– 10415Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Buckalew N, Haut MW, Morrow L, Weiner D: Chronic pain is associated with brain volume loss in older adults: preliminary evidence. Pain Med 2008; 9: 240– 248Crossref, Google Scholar

49 World Health Organization: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2001Google Scholar

50 World Health Organization: The World Health Report: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2002Google Scholar

51 Bruce ML: Depression and disability in late life: directions for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9: 102– 112Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Chisholm D: Disability in older adults with depression (doctoral dissertation). Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Department of Occupational Therapy 2005Google Scholar

53 Rogers JC, Holm MB, Goldstein G, McCue M, Nussbaum PD: Stability and change in functional assessment of patients with geropsychiatric disorders. Am J Occup Ther 1994; 48: 914– 918Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Hays JC, Steffens DC, Flint EP, Bosworth HB, George LK: Does social support buffer functional decline in elderly patients with unipolar depression? Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1850– 1855Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Katz P (ed): Function, Disability, and Psychological Well-Being. Falls Church, VA, Karger, 2004Google Scholar

56 Parmelee PA, Harralson TL, Smith LA, Schumacher HR: Necessary and discretionary activities in knee osteoarthritis: do they mediate the pain-depression relationship? Pain Med 2007; 8: 449– 461Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, Mulsant BH, Rollman BL, Dew MA, Schulz R, Reynolds CF 3rd: The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9: 113– 135Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Bruce M, Seeman T, Merrill S, Blazer DG: The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Public Health 1994; 94: 1796– 1799Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JT, Guralnik JM: Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health 1999; 89: 1346– 1352Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT: Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence: unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes [see comment]. JAMA 1995; 273: 1348– 1353Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Kennedy GJ, Kelman HR, Thomas C: The emergence of depressive symptoms in late life: the importance of declining health and increasing disability. J Commun Health 1990; 15: 93– 104Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Roberts RE, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ, Strawbridge WJ: Does growing old increase the risk for depression? Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 1384– 1390Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Zeiss AM, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR: Relationship of physical disease and functional impairment to depression in older people. Psychol Aging 1996; 11: 572– 581Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Kempen GI, Sullivan M, van Sonderen E, Ormel J: Performance-based and self-reported physical functioning in low-functioning older persons: congruence of change and the impact of depressive symptoms. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999; 54: P380– P386Google Scholar

65 Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD, Stump TE, Nienaber NA, Hui SL, Tierney WM: Mortality, symptoms, and functional impairment in late-life depression. J Gen Intern Med 1998; 13: 746– 752Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Koenig HG, George LK: Depression and physical disability outcomes in depressed medically ill hospitalized older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 6: 230– 247Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Ormel J, Von Korff M, Van den Brink W, Katon W, Brilman E, Oldehinkel T: Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients. Am J Public Health 1993; 83: 385– 390Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Morone N, Karp J, Lynch C, Bost J, El Khoudary S, Weiner D: Impact of chronic musculoskeletal pathology on older adults: a study of differences between knee OA and low back pain. Pain Med (in press)Google Scholar

69 Onen SH, Alloui A, Gross A, Eschallier A, Dubray C: The effects of total sleep deprivation, selective sleep interruption and sleep recovery on pain tolerance thresholds in healthy subjects. J Sleep Res 2001; 10: 35– 42Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Lamberg L: Chronic pain linked with poor sleep; exploration of causes and treatment. JAMA 1999; 281: 691– 692Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Means-Christensen AJ, Roy-Byrne PP, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, Stein MB: Relationships among pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Depress Anxiety 2008; 25: 593– 600Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Costa P, Tobin JD, Herbst JH, Hochberg MC: The relationship of anxiety and depression with self-reported knee pain in the community: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Arthritis Care Res 1999; 12: 3– 7Crossref, Google Scholar

73 McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman I. Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA, Educational and Industrial Testing Services, 1971Google Scholar

74 Casten RJ, Parmelee PA, Kleban MH, Lawton MP, Katz IR: The relationships among anxiety, depression, and pain in a geriatric institutionalized sample. Pain 1995; 61: 271– 276Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Karp JF, Reynolds CF 3rd, Butters MA, Dew MA, Mazumdar S, Begley AE, Lenze E, Weiner DK: The relationship between pain and mental flexibility in older adult pain clinic patients. Pain Med 2006; 7: 444– 452Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Weiner DK, Rudy TE, Morrow L, Slaboda J, Lieber S: The relationship between pain, neuropsychological performance, and physical function in community-dwelling older adults with chronic low back pain. Pain Med 2006; 7: 60– 70Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Shin YH, Hur HK, Pender NJ, Jang HJ, Kim M-S: Exercise self-efficacy, exercise benefits and barriers, and commitment to a plan for exercise among Korean women with osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Int J Nurs Stud 2006; 43: 3– 10Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Fiatarone Singh MA: Exercise to prevent and treat functional disability. Clin Geriatr Med 2002; 18: 431– 462Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, Khatri P, Doraiswamy M, Moore K, Craighead WE, Baldewicz TT, Krishnan KR: Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med 2000; 62: 633– 638Crossref, Google Scholar

80 North TC, McCullagh P, Tran ZV: Effect of exercise on depression. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1990; 18: 379– 415Google Scholar

81 Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Arean P: Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11: 46– 52Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Noël PH, Lin EH, Areán PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C; IMPACT Investigators: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 2836– 2845Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Huge V, Schloderer U, Steinberger M, Wuenschmann B, Schöps P, Beyer A, Azad SC: Impact of a functional restoration program on pain and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain. Pain Med 2006; 7: 501– 508Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Weiner DK: Office management of chronic pain in the elderly. Am J Med 2007; 120: 306– 315Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell I, Hebert L: The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum 1995; 38: 19– 28Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Abeles M, Clark P, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990. Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33: 160– 172Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Clauw DJ, Schmidt M, Radulovic D, Singer A, Katz P, Bresette J: The relationship between fibromyalgia and interstitial cystitis. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31: 125– 131Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Goldenberg D, Mayskiy M, Mossey C, Ruthazer R, Schmid C: A randomized double-blind crossover trial of fluoxetine and amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39: 1852– 1859Crossref, Google Scholar

89 Norregaard J, Volkmann H, Danneskiold-Samsoe B: A randomized controlled trial of citalopram in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain 1995; 61: 445– 449Crossref, Google Scholar

90 Gendreau RM, Thorn MD, Gendreau JF, Kranzler JD, Ribeiro S, Gracely RH, Williams DA, Mease PJ, McLean SA, Clauw DJ. Efficacy of Milnacipran in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2005; 32: 1975– 85Google Scholar

91 Sayar K, Aksu G, Ak I, Tosun M: Venlafaxine treatment of fibromyalgia. Ann Pharmacother 2003; 37: 1561– 1565Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Lithner F: Venlafaxine in treatment of severe painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 1710– 1711Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Bradley RH, Barkin RL, Jerome J, DeYoung K, Dodge CW: Efficacy of venlafaxine for the long term treatment of chronic pain with associated major depressive disorder. Am J Ther 2003; 10: 318– 323Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Pertovaara A: Noradrenergic pain modulation. Prog Neurobiol 2006; 80: 53– 83Crossref, Google Scholar

95 Westlund KN, Zhang D, Carlton SM, Sorkin LS, Willis WD: Noradrenergic innervation of somatosensory thalamus and spinal cord. Prog Brain Res 1991; 88: 77– 88Crossref, Google Scholar

96 Sindrup SH, Bach FW, Madsen C, Gram LF, Jensen TS: Venlafaxine versus imipramine in painful polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology 2003; 60: 1284– 1289Crossref, Google Scholar

97 Whyte EM, Basinski J, Farhi P, Dew MA, Begley A, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF: Geriatric depression treatment in nonresponders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65: 1634– 1641Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA, Smith JM: Antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of panic disorder. Neuropsychobiology 1993; 27: 150– 153Crossref, Google Scholar

99 Berlant J, van Kammen DP: Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report [see comment]. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 15– 20Crossref, Google Scholar

100 Lipper S, Davidson JR, Grady TA, Edinger JD, Hammett EB, Mahorney SL, Cavenar JO Jr: Preliminary study of carbamazepine in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatics 1986; 27: 849– 854Crossref, Google Scholar

101 Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Pipe B, Bennett M: Antiepileptic drugs in the treatment of anxiety disorders: role in therapy. Drugs 2004; 64: 2199– 2220Crossref, Google Scholar

102 Chouinard G, Beauclair L, Belanger MC: Gabapentin: long-term antianxiety and hypnotic effects in psychiatric patients with comorbid anxiety-related disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1998; 43: 305Crossref, Google Scholar

103 Pande AC, Pollack MH, Crockatt J, Greiner M, Chouinard G, Lydiard RB, Taylor C, Dager SR, Shiovitz T: Placebo-controlled study of gabapentin treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20: 467– 471Crossref, Google Scholar

104 Pande AC, Feltner DE, Jefferson JW, Davidson JRT, Pollack M, Stein MB, Lydiard RB, Futterer R, Robinson P, Slomkowski M, DuBoff E, Phelps M, Janney CA, Werth JL: Efficacy of the novel anxiolytic pregabalin in social anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled, multicenter study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24: 141– 149Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Harden CL: The co-morbidity of depression and epilepsy: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment. Neurology 2002; 59 ( 6 suppl 4): S48– S55Crossref, Google Scholar

106 Pariente A, Dartigues J-F, Benichou J, Letenneur L, Moore N, Fourrier-Reglat A: Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging 2008; 25: 61– 70Crossref, Google Scholar

107 Stewart SA: The effects of benzodiazepines on cognition. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66 ( suppl 2): 9– 13Google Scholar

108 Hanly P, Powles P: Hypnotics should never be used in patients with sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res 1993; 37 ( suppl 1): 59– 65Crossref, Google Scholar

109 Lavie P: Insomnia and sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med 2007; 8 ( suppl 4): S21– S25Google Scholar

110 Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH: Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts [see comment] [erratum appears in Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:298]. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 2716– 2724Crossref, Google Scholar

111 Walker EA, Keegan D, Gardner G, Sullivan M, Katon WJ, Bernstein D: Psychosocial factors in fibromyalgia compared with rheumatoid arthritis: I. Psychiatric diagnoses and functional disability. Psychosom Med 1997; 59: 565– 571Crossref, Google Scholar

112 Esenyel M, Caglar N, Aldemir T: Treatment of myofascial pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 79: 48– 52Crossref, Google Scholar

113 Faucett JA: Depression in painful chronic disorders: the role of pain and conflict about pain. J Pain Symp Manage 1994; 9: 520– 526Crossref, Google Scholar

114 Buckelew SP, Huyser B, Hewett JE, Parker JC, Johnson JC, Conway R, e Kay DR: Self-efficacy predicting outcome among fibromyalgia subjects. Arthritis Care Res 1996; 9: 97– 104Crossref, Google Scholar

115 McCain GA, Bell DA, Mai FM, Halliday PD: A controlled study of the effects of a supervised cardiovascular fitness training program on the manifestations of primary fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31: 1135– 1141Crossref, Google Scholar

116 Burckhardt CS, Mannerkorpi K, Hedenberg L, Bjelle A: A randomized, controlled clinical trial of education and physical training for women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 1994; 21: 714– 720Google Scholar

117 Goldenberg DL: Fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and myofascial pain syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1994; 6: 223– 233Crossref, Google Scholar

118 Unutzer J, Ferrell B, Lin E, Marmon T: Pharmacotherapy of pain in depressed older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52: 1916– 1922Crossref, Google Scholar