Patient Management Exercise Schizophrenia

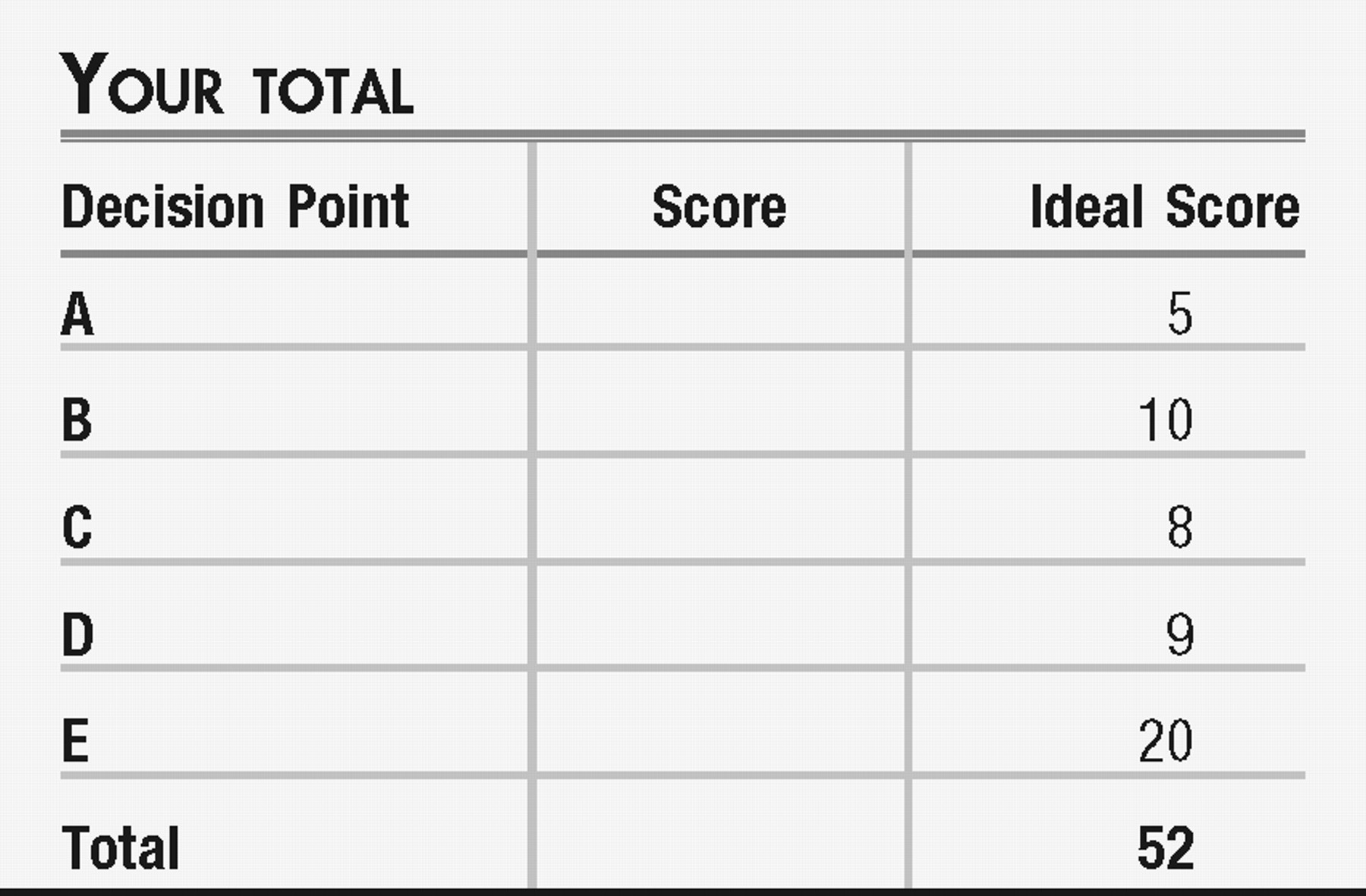

This exercise is designed to test your comprehension of material presented in this issue of FOCUS as well as your ability to evaluate, diagnose, and manage clinical problems. Answer the questions below, to the best of your ability, on the basis of the information provided, making your decisions as you would with a real-life patient. Questions are presented at “decision points” that follow a section that gives information about the case. One or more choices may be correct for each question; make your choices on the basis of your clinical knowledge and the history provided. Read all of the options for each question before making any selections. You are given points on a graded scale for the best possible answer(s), and points are deducted for answers that would result in a poor outcome or delay your arriving at the right answer. Answers that have little or no impact receive zero points. On questions that focus on differential diagnoses, bonus points are awarded if you select the most likely diagnosis as your first choice. At the end of the exercise you will add up your points to obtain a total score.

VIGNETTE PART 1

You are an emergency room psychiatrist. A young man, 18 years of age, is brought in by ambulance after he “destroyed” the trailer in which he and his mother had been living. The precipitant is not clear. The young man's mother accompanied him to the psychiatric emergency room. Two nurses and an emergency room technician help the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) team to transfer the patient from the ambulance to a hospital gurney where he is placed in four-point restraints by three hospital security officers owing to his continuing aggressive and assaultive behavior. With a great deal of difficulty you check the patient's vital signs (heart rate 120 beats per minute, blood pressure 180/85 mm Hg, respiratory rate 20, and temperature 98.4°F) and examine the patient grossly for any obvious signs of trauma or injury. He is disheveled, malodorous, and appears to have been wearing the same torn jeans and filthy T-shirt for some time. He is average height and weight for his age but appears older given his unkempt appearance. You attempt to speak with him, but he refuses to answer you, and you notice his hands and teeth are clenched tightly. For the most part, he stares at the ceiling, but occasionally his eyes dart around as if someone else is talking to him.

The EMS team reports that he was silent after an initial struggle with police to remove him from his home. His mother tells you he started behaving “strangely” approximately 3 months ago, insisting that their trailer was under surveillance and there were men following him whom he did not know, but he was sure they were from the government and meant to harm him. He stopped leaving the trailer and quit taking showers. He stayed up all night watching the TV without the sound on and slept most of the day. Two weeks ago he began removing some of the plumbing in the trailer because he said it was “bugged.” The patient's mother works at a paper mill; she said that her son started calling her cell phone up to 10 times a day to be sure she was “safe.”

While you are attempting to get history from the patient's mother he begins to yell obscenities at a nurse who is standing nearby. The mother denies his taking any medications of any sort. She tells you he has been smoking her cigarettes because “he has been running out of his more and more” and this bothers her because “smokes are so expensive now. I cannot afford to buy so many.” She is not sure if he uses street drugs, but he does not drink alcohol at home where he spends most of his time. He has no general medical problems. During this interview, the patient's agitation is escalating. You see him struggling with the leather restraints until he manages to free his right leg. He begins kicking the wall beside the gurney. Several people in the waiting room watch the proceedings anxiously.

Decision Point A

Given what you know about the patient and the behaviors you are witnessing, what is the most appropriate first step you should take in managing this patient? Points awarded for correct and incorrect answers are scaled from best (+5) to unhelpful but not harmful (0) to dangerous (−5).

| A1. ____ | Remove the remaining restraints yourself as these are obviously the cause of his worsening agitation. Triage him as the most urgent case in the emergency room and ask him to accompany you into the closest open interview room. |

| A2. ____ | Ask the security officers to remove the remaining restraints as these are obviously the cause of his worsening agitation. Triage him as the most urgent case in the emergency room and ask him to accompany you into the closest open interview room. |

| A3. ____ | Ask the security officers to restrain the patient's freed leg and then wheel him to the isolation room. Once he is safely restrained and inside the room, ask everyone to leave the patient alone and close the door. Continue your interview with the patient's mother. |

| A4. ____ | Ask the security officers to restrain the patient's freed leg and then wheel him to the isolation room. Try to calm the patient by speaking to him in a calm voice. If this is unsuccessful, ask the patient if he is willing to take an oral medication that will help him relax. Tell him if he does not take the oral medication you will have to give him an injection of medicine that will help him relax. This patient is severely agitated, so medications must be delivered promptly. |

| A5. ____ | Ask the security officers to restrain the patient's freed leg and then wheel him to the isolation room. Give him an injection of haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and benztropine 1 mg. Wait 15–20 minutes for the medications to take effect. If he is still combative, give another identical injection. |

VIGNETTE PART 2

The patient calms down considerably after he agreed to take a total of olanzapine (orally disintegrating tablet) 10 mg, given in 5-mg doses 1 hour apart. He is no longer in restraints but prefers to remain in the isolation room where he is resting on the gurney. The door to the isolation room is kept open, and a nurse is sitting in a chair just outside the doorway. He asks to speak with you. He tells you that he knows his trailer is bugged by the FBI and the CIA because, “I know too much. They have been watching me and my mother.” He expresses worry that the FBI or the CIA plans to kidnap his mother to “make me talk.” This is why he has been calling her. “But she does not get it. She does not get it. She does not get it. I have to get it.”

He denies feeling sad or hopeless but endorses feeling helpless to stop the government agencies from “harassing us.” He has thought about killing himself in the past but denies current suicidal thoughts. The last time he was suicidal was approximately 1 month ago. You decide to make a gentle assumption that he is hearing voices and ask, “What are they telling you?” He closes his eyes and says, “It is always about how I need to kill myself or kill my mother because that is what the government wants. That is how I knew I had to get rid of the pipes.” He thought about killing his mother to save her from the FBI and the CIA, but then decided against that because “Then they've got me, they've got me, they get me, they get me. It is me, it is me, it is me, it is me.” He tells you he has found “poison” in some of the food his mother has brought home for him to eat. Sometimes he only eats potato chips for days, which he asserts cannot be poisoned because they are “crispy.”

He said he lost his job at a fast-food restaurant two months ago because “They did not get it, did not get it, they did not get it. It is me.” He quit high school at the beginning of 11th grade. He does not see friends anymore because he is convinced they have been compromised by the government and are spying on him. “I do see Nick every day, though. He lives two rows over. We smoke weed together.” Then he adds, “Don't tell my mother.” He then turns away on the gurney and seems to sleep.

You speak with his mother. She tells you that he used to be a B student until the end of 10th grade when his grades started to deteriorate. He worked during that summer at a fast-food restaurant and seemed to do well, although he had a few bouts of feeling low. He was never violent or aggressive. At some point early in 11th grade he got into a physical altercation with another student and threatened to kill him. He was taken from school by ambulance to your psychiatric emergency room, evaluated, found to be upset but not a danger to anyone or to himself, and was discharged to follow-up at an outpatient child and adolescent psychiatric clinic connected to your hospital. His mother said he never went to any appointments because he insisted, “I'm not crazy. You are.” He had never taken any psychiatric medications, was never previously hospitalized for psychiatric reasons, and, although he was staying home more and more, his mother never felt the need to pressure her son into treatment. “I have to work to support us,” she tells you. “I cannot keep track of everything.”

Decision Point B

Given what you know about this patient so far, what would be your next steps in assessing the patient? Points awarded for correct and incorrect answers are scaled from best (+5) to unhelpful but not harmful (0) to dangerous (−5).

| B1. ____ | The patient is clearly schizophrenic and needs to be taking antipsychotic medications. Arrange with his mother for the patient to be seen in your outpatient department, and as soon as the patient is stable, discharge him home to his mother's care. |

| B2. ____ | The patient is clearly schizophrenic and needs to be taking antipsychotic medications. Given the good response from olanzapine, give the mother a prescription for a month's supply of olanzapine 10 mg PO at bedtime, arrange the first available appointment at your outpatient department which is in 5 days, and explain to her that she should bring him back to the psychiatric emergency room if he again decompensates. |

| B3. ____ | Order the following laboratory values and studies: rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, vitamin B12, folate, Lyme disease titer, complete blood count with differential, Chem-7, liver function tests, thyroid-stimulating hormone, urinalysis, urine toxicology screen, computed tomographic (CT) scan of the head without contrast, and an electrocardiogram (ECG). Obtain further history, especially a family history of psychiatric illness. |

| B4. ____ | If you are able to rule out a general medical cause to his psychosis, start aripiprazole 5 mg PO treatment for the patient at bedtime and discharge to the care of his mother. Schedule the first available appointment at your outpatient department which is in 5 days and explain to her that she should bring him back to the psychiatric emergency room if he again decompensates. |

| B5. ____ | Order the laboratory values and studies in answer B3 and then admit the patient to an adolescent inpatient unit for further evaluation and safety. |

Decision Point C

Given what you know about this patient, what is your differential diagnosis? Points are given for correct answers, and negative points for incorrect answers.

VIGNETTE PART 3

Once it was determined the patient did not have an underlying organic cause to his psychiatric symptoms, he was hospitalized in an adolescent inpatient unit. His urine toxicology screen was negative for substances, including cannabis. He is started on risperidone, which is quickly titrated to 3 mg BID over the course of 2 weeks with good results. The patient no longer appears agitated, is sleeping well, is eating all of his meals, and speaks freely with you. However, he is still mostly isolative on the unit, preferring to listen to music through headphones or watch TV with some peers. He tells you that he has gone without sleep for 2–3 days at a time, but feels exhausted all day when he is unable to sleep. He admits he had been hearing a voice in his head telling him what he was doing as he did it, such as “you are now walking,” or “you are touching the door.” He also heard two different voices talking to him or about him, sometimes saying “I should kill myself,” or “I have to kill my mother.” He still thinks you are recording him, but he tells you, “if that is what you gotta do, then that is what you gotta do.” He no longer believes the food in the unit is poisoned, although he does recall thinking that before. He has poor recollection of the details surrounding his admission to the hospital.

He says he does not have any hobbies other than “smoking cigarettes” and listening to music. Until recently, however, he typically would go outside and walk and visit his neighbor, and previously he spent a great deal of time doing schoolwork. He says he usually has good energy, but finds it difficult to concentrate more and more. “It did not used to be like that,” he tells you. His appetite now is strong, and he believes it is because of the medication.

Further history revealed that his mother was in treatment for depression, his biological father and paternal uncle both suffered from schizophrenia, and he had a paternal great aunt who lived in a state psychiatric hospital for many years but died before the patient was born. According to the patient's mother, she noticed that her son was “a little slow to speak,” a little clumsy, and did not socialize very well with age-appropriate peers as he grew up. Her pediatrician told her he was within the normal range of development and an evaluation of developmental delays was not pursued. He never had a girlfriend, nor did he seem particularly interested in romantic pursuits. By 11th grade, however, he began to isolate more, he seemed outwardly depressed, he stopped doing much of his homework, and his grades began to slide. Three months into the school year, 4 months before this emergency room visit, the patient quit school and refused to leave the trailer except to visit a neighbor where he allegedly smoked marijuana, and his mother noted that she often caught him talking to himself. At first, she said, he would look frightened if she found him speaking out loud to himself, as if he were in trouble. Eventually, he did not seem to care if he was talking to himself in front of her. She never understood what he was talking about, but she recalls he was anxious and nervous, looking around the trailer as if he were being watched. “Then he started telling me these crazy things about the government spying on us, that our trailer was bugged.”

They began to argue more. She tried to stop him from removing wiring, dismantling a lamp, opening up the back of the TV, and other “odd behaviors,” but he would “fly into a rage at me” and threaten to hit her “for my own good.” He would scream loudly to leave him alone. Over the past 3 weeks she often found him sobbing in his room and unable to tell her why except for repeating, “Why can't I just die?” Their fights quickly intensified both verbally and physically. The patient shoved his mother a couple of times but never hit her. She said she was now fearful he would harm her. He also began threatening to kill himself with a gun. They did not own a gun, but she thought the neighbor might own one.

Decision Point D

From what you have learned about the patient, what is the most important factor you should explore next? Points awarded for correct and incorrect answers are scaled from best (+5) to unhelpful but not harmful (0) to dangerous (−5).

| D1. ____ | Obtain as much collateral information as is possible, from the mother, other doctors, teachers, and even friends. |

| D2. ____ | Call the police to investigate the patient's neighbor who may be supplying the patient with marijuana. |

| D3. ____ | Evaluate the mother for psychiatric illness and recommend treatment. |

| D4. ____ | Evaluate the patient's suicidal and homicidal risks. Provide education to the patient's mother about how to “sterilize” her home from easy methods of self-harm or suicide, such as locking away pills, knives, and removing any firearms from the home. |

| D5. ____ | Contact the FBI and the CIA and determine whether your patient is actually the subject of an inquiry or investigation. |

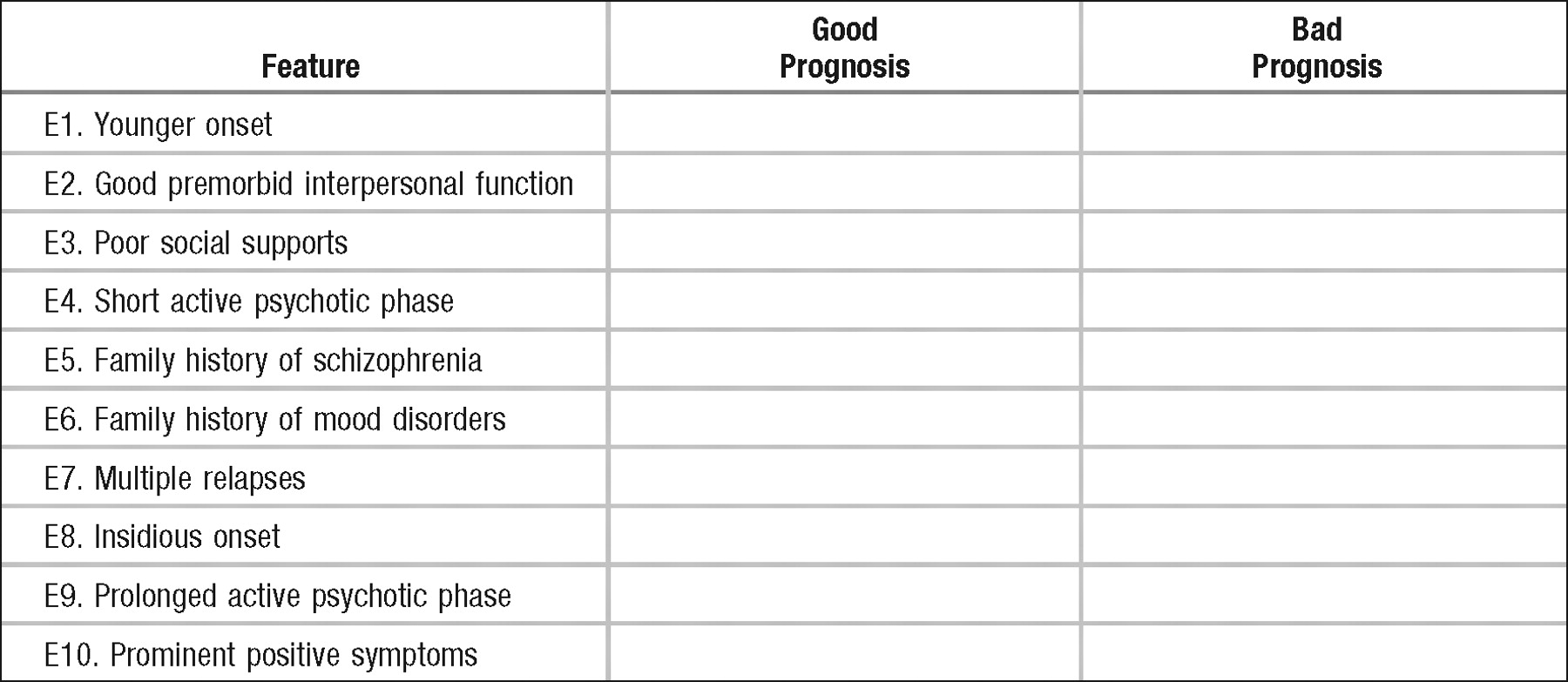

Decision Point E

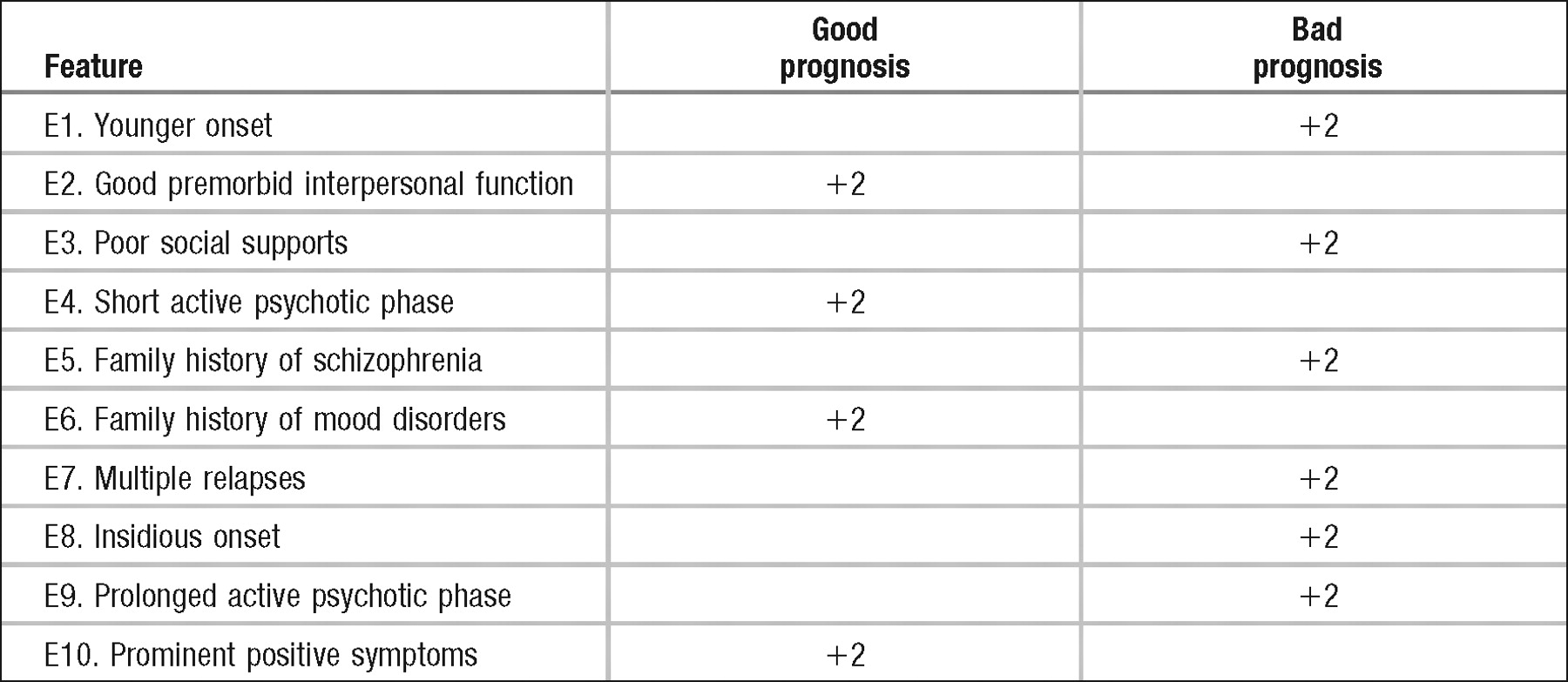

Which of the following features of schizophrenia represent good or bad prognoses? Answer by checking the correct box. +2 points are given for correct answers, −2 points for incorrect answers.

ANSWERS: SCORING, RELATIVE WEIGHTS, AND COMMENTS

Decision Point A

Generally, management of an acutely agitated patient in the emergency setting should begin with attempts to deescalate the patient using nonpharmacological methods. The clinician should begin by making sure both he or she and the patient have easy access to an escape route from this engagement. Additionally, by speaking in a nonconfrontational, soft, friendly tone, exhibiting body language that is nonthreatening, avoiding direct eye contact, and maintaining a safe distance to avoid encroachment upon the patient's personal space have been shown as preventative against provoking stress and anxiety in the patient. Immediate assessment of suicidal and/or homicidal ideation should be performed. If these measures are sufficient, the use of chemical or physical restraints may be avoided. Otherwise, attempts to use pharmacological interventions should be tried. It may become necessary to physically restrain the patient and then use medications to calm the patient. Prolonged use of physical restraints while a patient struggles can lead to unintentional self-harm, hyperkalemia, rhabdomyolysis, and cardiac arrest, and subsequently the use of medications can reduce these risks.

If a patient is physically restrained, there must be regular and frequent evaluation of the patient's cardiovascular and neurological status and examination of the patient's extremities, respiration, and hemodynamics. These assessments should be clearly documented, along with the reason for the restraint procedure(s), or continuation of the restraint procedure(s).

| A1. ____ | −5 The first step in managing an acutely agitated patient is for staff to attempt to calm the patient by talking to him or her. If this is not possible, staff who are trained in safe restraint procedures should restrain the patient in a way that minimizes risk of harm to the patient or to staff. Removing restraints for an acutely agitated patient, especially in an emergency room waiting area, is dangerous as the patient is probably frightened and confused, and there is a high likelihood of his or her causing harm to themselves or to others. You should never place yourself or anyone else in a closed room with an acutely agitated and possibly psychotic patient who is not medicated or restrained. |

| A2. ____ | −5 It is an appropriate practice to ask specially trained staff (here, the security officers) to apply restraints. Restraining the freed leg is important as this patient is using his leg in such a way that he might hurt himself or others. However, despite finding the most appropriate person to remove restraints, this particular patient is currently too dangerous in his current state and the restraints should not be removed. Removing him from the common area of the emergency room will keep others safe and not contribute to the escalation of other waiting patient's symptoms. Keeping the patient in a closed room without medications or restraints may help calm the patient, but the room should not have furniture or fixtures that can be used by the patient to harm himself or others. As soon as it is possible, medications should be used to help calm the patient so that the restraints may be removed. In addition, the patient should be monitored either by close-circuit TV if available to the emergency room or by frequent 15-minute checks by staff, which is a Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and ethical “must.” |

| A3. ____ | −5 Leaving the patient alone in restraints when he is clearly in a severely agitated state without medications is not likely to relieve his symptoms and could worsen his symptoms. Use of trained staff to manipulate restraints is appropriate, especially because this patient may hurt himself or others. Removing him from the common area of the emergency room will keep others safe and not contribute to the escalation of other, waiting patient's symptoms. First attempting to calm the patient with a soft voice can often deescalate an agitated patient and avoid the need for more aggressive measures. If this is not possible, the use of restraints should be used to help the patient safely receive a short-acting neuroleptic with or without an anxiolytic. Benztropine, an anticholinergic medication, is often used in combination with first-generation neuroleptics to reduce the risk of drug-induced extrapyramidal movements, rigidity, tremor, and gait disturbances |

| A4. ____ | +5 Because of the severity of this particular patient's agitation, his symptoms should be treated with medications as quickly as possible to avoid any potential harm he might cause himself or others, despite the restraints. It is preferable to use a second-generation neuroleptic such as risperidone or olanzapine, both of which come in rapidly dissolving tablets to minimize the potential for “cheeking” or spitting out the medication. In a young male patient, the atypical agents are preferred over first-generation neuroleptics such as haloperidol because the latter is associated with a higher risk of drug-induced extrapyramidal movements, rigidity, tremor, and gait disturbances, or the more serious and life-threatening neuroleptic malignant syndrome. If the patient is unable to take the tablet or refuses, most states allow for emergency administration of an injectable parenteral neuroleptic such as the first-generation neuroleptic haloperidol or second-generation neuroleptics such as ziprasidone and olanzapine. The choice of whether to use first- or second-generation neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, or a combination of the two should be considered on a case-to-case basis, taking into account the patient's previous or current psychiatric medications, his or her response to those medications, and his or her age, sex, general medical comorbidities, or risk factors. |

| A5. ____ | −3 In practice, especially in the emergency setting with an acutely agitated, possibly psychotic patient, there is an urgency to reduce potential for harm to the patient or to others. Waiting 15–20 minutes for the medications to take effect may or may not be enough time. Generally, the purpose of using medications is to calm the patient and reduce the symptoms but not to sedate the patient. The overarching principle is maintaining patient and staff safety. However, the use of multiple medications, including an atypical antipsychotic in a male patient is potentially dangerous. |

Decision Point B

Generally, when one evaluates a patient in an acute psychotic state, it is very important to obtain as much collateral information as possible as this patient is unlikely to give a coherent or accurate history. The possible etiologies of psychosis are numerous and the clinician should begin with a general medical and psychiatric examination, including patient and family history, level of premorbid functioning, chronology, intensity of symptoms, general medical history, substance use history.

| B1. ____ | −5 The patient may appear to be schizophrenic; however, you cannot yet make this diagnosis without first ruling out any general medical causes of his psychosis. Additionally, he has demonstrated that he is a danger to himself and to his mother. His symptoms have been worsening over 3 months, but you have been given clues that a prodrome of illness may have begun approximately 2 years ago. This patient should be hospitalized for further evaluation, stabilization, safety, and treatment. |

| B2. ____ | −3 See B1. Additionally, the patient's response to olanzapine (orally disintegrating tablet) 10 mg comprised primarily a reduction of his behavioral dyscontrol and moderate organization of his thought process. However, he is still in thought-disordered and perseverating phrases, demonstrating some looseness of associations, and delusions of surveillance, paranoia, and persecution. As stated above in B1, this patient should be hospitalized for further evaluation, stabilization, safety, and treatment. |

| B3. ____ | +5 There are many medical and neurological conditions that can present with psychosis. Medical conditions associated with psychosis include neurological, infectious, metabolic, oncological, and immunological processes, as well as alcohol and drug intoxication or withdrawal and vitamin deficiency. Among the most common presentations of such changes in mental status include neurological disorders including meningitis, encephalitis, cerebrovascular accidents, subarachnoid hemorrhages, and subdural hematoma. Other, less common neurological causes of psychosis include brain tumors, metastases to the central nervous system, seizure disorders, or a neurodegenerative disease (especially with young children). Metabolic disorders include myxedema, thyrotoxicosis, Cushing's disease, and less commonly diabetes. The anoxia from pulmonary disease can present with psychotic-like symptoms. Other considerations include porphyria or Wilson's disease, both of which may present first with psychiatric symptoms before the physical etiology becomes clear. Lupus erythematosus can cause an “organic” psychosis, or the treatment for lupus, corticosteroids, can also cause psychosis. Deficiencies in nicotinic acid or thiamine as well as lead intoxication can cause psychotic symptoms. Medications the patient may be taking, either prescription or street drugs, can also cause psychotic symptoms. Withdrawalsymptoms from some of these medications or drugs can also present as psychosis. In this latter category, urine toxicology screening is necessary as these patients are often unable or unwilling to reveal whether they ingested medications or street drugs. |

| There are no official guidelines for which laboratory values or studies to order. It has become commonplace for psychiatrists minimally to order a complete blood count with differential, liver function tests, thyroid-stimulating hormone, urinalysis, and urine toxicology screen for most psychiatric patients to help rule out organic causes of psychiatric symptoms or to check organ function if medications are to be used. Additionally, an ECG has become especially important as many of the neuroleptics (as well as other classes of psychoactive medications) affect cardiac conduction, often by widening QTc intervals. In younger, healthy patients with no known history of heart disease, obtaining an ECG is not as important as initially thought. However, there is no consensus concerning the other laboratory values and studies and many clinicians choose to err on the side of safety. Others believe that the clinical and epidemiological picture should direct which laboratory values and studies should be ordered. For example, if this patient demonstrated focal neurological signs or a history of head trauma, a CT scan of the head without contrast would be indicated. Many neurologists would prefer a magnetic resonance imaging scan to evaluate more temporally distant insults as well. Even though the yield for a positive result is quite low, most clinicians prefer to rule out a general medical cause to the symptoms no matter the cost because the results affect treatment decisions. | |

| B4. ____ | −5 Despite the reasonable approach of first eliminating organic causes to the patient's symptoms, he should not be discharged but hospitalized for the same reasons given in answers B1 and B2. |

| B5. ____ | +5 Most hospitals insist upon many of these studies before they will accept a patient to their inpatient unit. Additionally, before the patient leaves the emergency department, “organic” causes should be ruled out to avoid hospitalizing the patient in a psychiatric unit when a medical unit is necessary to further evaluate and treat medical illness with psychiatric symptoms. |

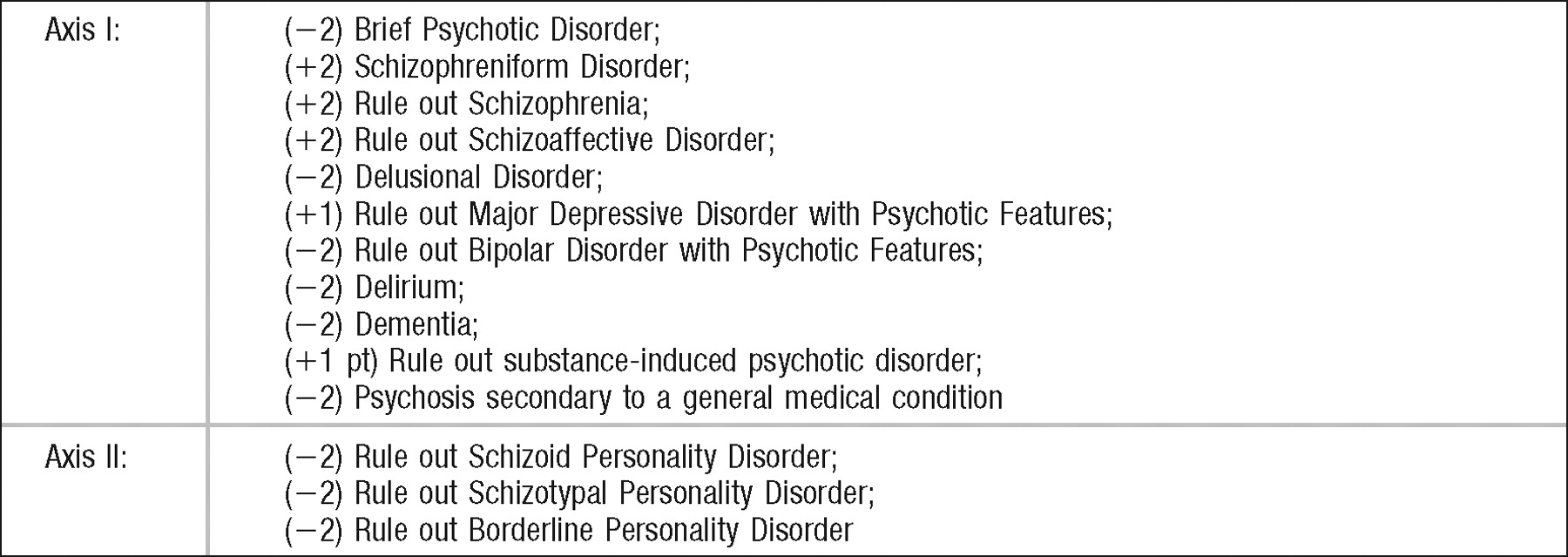

Decision Point C

Brief Psychotic Disorder: −2

This patient had symptoms greater than 1 month in duration. For this diagnosis, the symptoms must last from 1 day to 1 month.

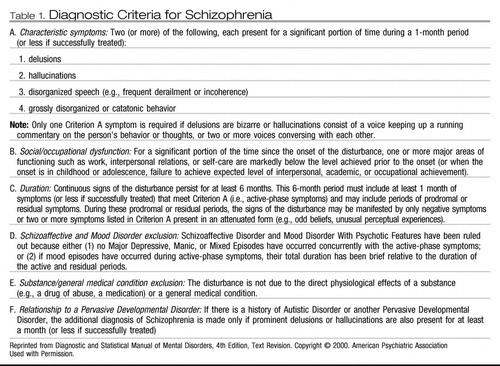

Diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia according to DSM-IV-TR are shown in Table 1.

Schizophreniform Disorder: +2

We are told the patient's symptoms worsened over the previous 3 months. There may have been prodromal symptoms lasting longer, especially given the patient's quitting school 4 months earlier. Aggressive behavior is associated with schizophrenia, although violence is not. Risk factors for aggression in schizophrenia are male gender; being poor, unskilled, uneducated, or unmarried; and having a history of prior arrests or a prior history of violence. This risk increases with comorbid alcohol or substance abuse, antisocial personality, or neurological impairment. Given the unreliability of the patient's history and mother's minimizing of previous symptoms, we cannot be certain the symptoms have been present for more than 6 months. Until we know better, or until more time has passed, the patient can safely be diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder. It should be noted, however, that approximately two-thirds of patients will proceed to schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

|

Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Schizophrenia

Rule out Schizophrenia: +2

The patient demonstrates two symptoms from Criterion A, including the voice of a running commentary and two voices conversing with each other. The caveats to this diagnosis are establishing criteria C through F. The time frame for the absolute length of his illness is difficult to determine given that the patient is a poor historian and his mother may have minimized his symptoms. The normal physical examination and normal results for laboratory values and studies make it unlikely that this patient has a general medical condition that could be causing the symptoms. The role of substance abuse (marijuana) was not ruled out, and further testing is necessary to absolutely rule out a pervasive developmental disorder. The patient did demonstrate “soft” neurological signs since he was a baby and was somewhat socially challenged, although he did manage to do very well in mainstream education until his symptoms worsened in 11th grade. Although it seems quite likely that this is the patient's primary diagnosis, clinicians should be careful when labeling a patient, especially an adolescent, with a diagnosis such as schizophrenia. If incorrect, this diagnosis could adversely affect the patient's ability to recover because of the stigma of this illness, both from the patient's perspective and from that of others who may learn of this patient's diagnosis. It will also affect future treatment considerations.

Rule out Schizoaffective Disorder: +2

This disorder occurs at approximately 10% the rate of schizophrenia and can be distinguished by the presence of a mood disorder, such as major depression and/or mania during a significant portion of the illness. However, there must be at least 2 weeks of psychotic symptoms in the absence of major mood symptoms to meet the criteria for schizoaffective disorder. This patient may have experienced major mood symptoms, or his insomnia could have been the result of not being able to sleep because of symptoms related to psychosis, such as voices, paranoid ideation, or other anxiety-provoking disturbances of thought content or form. Patients with schizophrenia often have a mood disturbance, such as depression, but it is not typically a major mood disturbance. Until a more clear history is determined, this illness remains a rule-out.

Delusional Disorder: −2

The patient's symptoms point more towards a schizophreniform disorder or schizophrenia than for a delusional disorder, which by criterion B of delusional disorder disqualifies this diagnosis. Additionally, the patient's delusions are quite bizarre. For a delusional disorder they should be non-bizarre.

Rule out Major Depressive Disorder with Psychotic Features: +1

The patient is described by his mother as appearing depressed, tearful for the past 3 weeks, voicing suicidal ideation, and isolating, with the patient endorsing difficulty concentrating. The patient's psychotic symptoms have been described in detail. He may have a major depressive disorder with psychotic features or perhaps a depressive disorder, but his primary diagnosis is more likely a psychotic disorder. The range of patients with schizophrenia who experience depressive symptoms ranges from 7% to 75%.

Rule out Bipolar Disorder with Psychotic Features: −2

The patient does not endorse classic or atypical symptoms of mania. His insomnia is more likely due to a depression or psychotic symptoms. The patient exhibits classic Schneiderian psychotic symptoms, including hearing a voice that offers a running commentary about his actions and two voices that speak either to him or to each other about him.

Delirium: −2

The patient was evaluated for general medical causes of his changed mental status and the findings were negative. He had no evidence of waxing or waning consciousness, and no evidence of sudden onset of symptoms.

Dementia: −2

Given the patient's age and normal physical findings, normal laboratory values and imaging studies, this diagnosis is highly unlikely.

Rule Out Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorder: + 1

Results of the patient's urine toxicology screen was negative, despite his assertion that he regularly smokes “weed.” Tetrahydrocannabinol has a very long half-life in the human body and can be detected up to 1 month or more after last use of the substance, especially if used regularly. Although it is highly unlikely that his symptoms are the result of current use of substances, the positive threshold of the urine toxicology screen may be too high for the amount the patient actually smoked, his illness may have begun as a result of his abuse of substances, or he may be using substances that are not readily discernible with a standard six-substance urine toxicology screen. There is also the possibility of a false-negative result. Care should be given to explore the patient's actual use of substances and alcohol, given his assertion that he does use marijuana regularly.

Psychosis Secondary to a General Medical Condition: −2

The patient has been examined and is physically healthy.

Schizoid Personality Disorder: −2

This patient probably has an axis I diagnosis, not a personality disorder. There was a prodrome to his illness and then a worsening of psychotic symptoms. His premorbid functioning was within the normal range.

Schizotypal Personality Disorder: −2

There is no pervasive pattern of social and interpersonal deficits. He does have many of the symptoms of a schizotypal personality disorder, such as odd beliefs, audio hallucinations, paranoid ideation, odd behaviors, and a lack of close friends. However, his symptoms are better accounted for by an axis I diagnosis.

Borderline Personality Disorder: −2

As above, there is no pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects. His symptoms are better accounted for by an axis I diagnosis.

Decision Point D

| D1. ____ | +3 This is a necessary step in evaluating any patient. In a patient with suspected schizophrenia, there is an assumption that the patient may be thought disordered and therefore unable to provide a cogent, accurate history. Additionally, this is a young patient who is unlikely to know his own developmental history, academic history, general medical history, or behavioral history as witnessed by the various individuals who know him. |

| D2. ____ | −5 Your job is not to be a police detective, but the patient's doctor. Although it would be informative to know more information about the patient's alleged marijuana abuse, the neighbor may have nothing to do with the situation. It is certainly not your responsibility to investigate a theoretical criminal matter. |

| D3. ____ | +1 The mother is not your patient. While speaking with her, you can ask about her own condition in terms of family psychiatric history or to provide support if she needs it. If she wants an evaluation and she does not have a psychiatrist or other clinician working with her, or if she wants a new clinician, you can certainly provide referrals. However, she has not presented to your psychiatric emergency room for herself, but brought in her son. She has not indicated to you that she is in any danger to herself or to others, so there is no need to treat her as a patient. It is good practice, however, to be empathetic to her concerns, listen carefully, and develop a good rapport as you will want her to be actively involved and appropriately educated on the treatment of her son. |

| D4. ____ | +5 This patient has expressed suicidal ideation in the past and has mentioned the use of a gun to kill himself. As many as 30% of schizophrenic patients attempt suicide and between 4 and 10% complete suicide. Suicidal behavior is prevalent in between 20 and 40% of schizophrenic patients. In this case, the patient experienced command auditory hallucinations, which have been found to increase the risk of suicide. The patient has also threatened his mother's life. It should be noted, however, that patients with schizophrenia do not generally demonstrate a higher risk for homicide than individuals within the general population. |

| D5. ____ | −5 Although it may be true that some people are being pursued by the FBI or the CIA, this is clearly not the case in this patient's presentation. This patient has paranoid ideation. |

Decision Point E

In general, a diagnosis of schizophrenia is not favorable. Only 10%–20% of schizophrenic patients were judged to have a favorable outcome 5–10 years after their first hospitalization. Interestingly, despite the development of novel antipsychotic medications and treatments and improvements in outpatient treatment, the overall prognosis of schizophrenia has changed little over the past century. It is estimated that more than 50% of schizophrenic individuals have worsening of symptoms or “downward drift” (as patients are less functional in society, their ability to care for themselves deteriorates as does their ability to earn income, resulting in a downward social and economic drift; this phenomenon is responsible for the mistaken impression that this illness is relegated to those of lower socioeconomic status), episodes of mood disorder, and, as stated above, a higher than average suicide rate. According to Kaplan and Sadock et al. 40%–60% of schizophrenics remain severely impaired throughout life. Positive symptoms, such as delusional thinking, often diminish gradually after the fifth decade of life leaving only the negative, residual symptoms.

Within the subtypes of schizophrenia, the paranoid subtype has the best overall prognosis and later age of onset. It is more common to see earlier, more insidious onset of symptoms in disorganized or undifferentiated subtypes which have much worse prognoses.

1 Alaghband-Rad J, McKenna K, Gordon CT, Albus KE, Hamburger SD, Rumsey JM, Frazier JA, Lenane MC, Rapoport JL: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: the severity of premorbid course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1273–1283Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Allen MH, Currier GW, Carpenter D, Ross RW, Docherty JP (Expert Consensus Panel for Behavioral Emergencies 2005). The expert consensus guideline series: Treatment of behavioral emergencies 2005. J Psychiatr Pract 2005; 11:(suppl 1)5–108Google Scholar

3 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

4 American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Nurses Association, National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems: Learning From Each Other: Success Stories and Ideas for Reducing Restraint/Seclusion in Behavioral Health. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2003Google Scholar

5 Bartels SJ, Drake RE. Depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: comprehensive differential diagnosis. Compr Psychiatry 1988; 29:467–483Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Caine ED. Clinical perspectives on atypical antipsychotics for treatment of agitation (review). J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67(suppl. 10):22–31Google Scholar

7 Cannon M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Taylor A, Murray RM. Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:449–456Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Collaborative Working Group on Clinical Trial Evaluations. Atypical antipsychotics for treatment of depression in schizophrenia and affective disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:(suppl 12)41–45Google Scholar

9 Dubin WR. Rapid tranquilization: antipsychotics or benzodiazepine? J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49(suppl):5–12Google Scholar

10 Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Cornblatt B, Friedman D, Marcuse Y, Rutschmann J, Simmens S, Devi F: Neurological, electrophysiological and attentional deviations in children at risk of schizophrenia, in Schizophrenia as a Brain Disease. Edited by Henn FA, Nasrallah HA. New York, Oxford University Press, 1982, pp 61–98Google Scholar

11 Gottesman II, Shields J. Schizophrenia: The Epigenetic Puzzle. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1982Google Scholar

12 Hill S, Petit J. The violent patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2000; 18:301–305Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Hughes DH, Kleespies PM. Treating aggression in the psychiatric emergency service. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:(suppl 4)1Google Scholar

14 Hyman SE. The suicidal patient, in Manual of Psychiatric Emergencies, 3rd ed. Edited by Hyman SE, Tesar GE. Boston, Little, Brown, 1994, p. 144Google Scholar

15 Koreen AR, Siris SG, Chakos M, Alvir J, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman J. Depression in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1643–1648Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Marder SR. A review of agitation in mental illness: treatment guidelines and current therapies (review). J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:(suppl 10)13–21Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Plomin R, Reiss D, Hetherington EM, How GW. Nature and nurture: genetic contributions to measures of the family environment. Dev Psychol 1994; 30:32–43Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Radomsky ED, Haas GL, Mann JJ, Sweeney JA. Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1590–1595Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Robson KS (ed). Manual of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, rev. ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, Inc, 1994Google Scholar

20 Rund DA, Ewing JD, Mitzel K, Votolato N. The use of intramuscular benzodiazepines and antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute agitation or violence in the emergency department (review). J Emerg Med 2006; 31:317–324Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 8th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2005Google Scholar

22 Salzman C, Green AI, Rodriguez-Villa F, Jaskiw GI. Benzodiazepines combined with neuroleptics for management of severe disruptive behavior. Psychosomatics 1986; 27:17–22Crossref, Google Scholar

23 San L, Arranz B, Escobar R. Pharmacological management of acutely agitated schizophrenic patients (review). Curr Pharm Des 2005; 11:2471–2477Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Sands JR, Harrow M. Depression during the longitudinal course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:157–171Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Simpson JC, Tsuang MT. Mortality among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:485–499Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Siris SG. Depression in schizophrenia: perspective in the era of “atypical” antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1379–1389Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Walker E, Lewis N, Loewy R, Palyo S. Motor dysfunction and risk for schizophrenia. Dev Psychopathol 1999; 11:509–523Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Walker EF, Savoie T, Davis D. Neuromotor precursors of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:441–451Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Watt N, Saiz C. Longitudinal studies of premorbid development of adult schizophrenics, in Schizophrenia: A Life-Course Developmental Perspective. Edited by Walker E. San Diego, Academic Press, 1991, pp 158–185Google Scholar

30 Woods SW, Millar TJ, Davidson L, Hawkins KA, Sernyak MJ, McGlashan TH. Estimated yield of early detection of prodromal or first episode patients by screening first-degree relatives of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res 2001; 52:21–27Google Scholar

31 Yildiz A, Sachs GS, Turgay A. Pharmacological management of agitation in emergency settings. Emerg Med J 2003; 20:339–346Crossref, Google Scholar