A Cautionary Tale About Boundary Violations in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis

Boundary violations are perhaps the most damaging of events to our profession and to our patients. Although the term is generally used to refer to major violations of a sexual nature, there is a broad range of lesser transgressions, which happen frequently in therapy and may even help catalyze the therapeutic work (1, 2). Some use the term “boundary crossings” to characterize these minor events. These events are not the focus of this article; however, there is a lively debate in the current analytic literature on the subject.

A striking phenomenon, discussed in this article, is that boundary violations are not limited to marginal practitioners (3). Some of our most revered pioneers as well as eminent current luminaries are among the violators (4). Although these are complex phenomena, I suggest that at least some of these violations are the result of therapists believing that they know what is best for certain patients and then acting on this “knowledge.” This is the way in which I see this report as a “cautionary tale.” I suggest as well that many of our most eminent predecessors may have been powerful role models for such misguided beliefs and actions, which in some cases have come to very unfortunate conclusions.

It is important that we understand the prevalence of boundary violations. There is not a great deal of hard data about this issue. Most research has involved self-report surveys of mental health professionals and has demonstrated a prevalence of 0.9–12% with a median figure of about 6% (5–14). Generally, male therapists are more involved in these violations than are female therapists with a ratio of about 3:1. There are repeat violators and, in some cases, high recidivism rates. Unfortunately, therapist sexual misconduct with child patients also occurs, but there are only a very few reported estimates of the incidence (15) although there are occasional reports in the popular press such as a recent one involving a prominent child psychotherapist.

A PROGRESSION: BOUNDARY CROSSINGS TO BOUNDARY VIOLATIONS

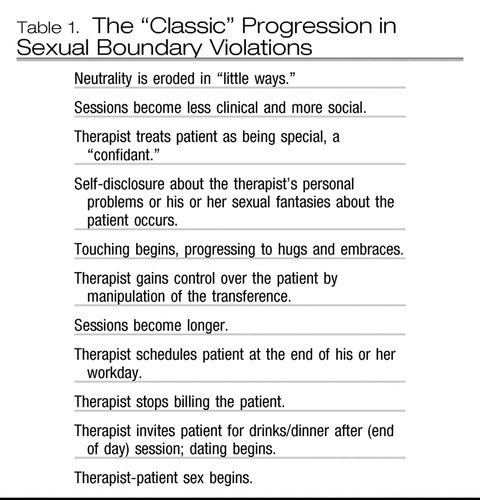

In some cases, there may be a “classic” progression, which might serve as a warning signal (Table 1) (16). The first steps involve erosion of neutrality in “little ways,” such as sessions becoming more social with the therapist treating the patient more as a “confidant.” A major warning signal should occur whenever touching begins. Transference manipulations may enable the therapist to gain greater control over the patient. Another serious warning is when the therapist stops billing the patient. The final steps include getting together for drinks/dinner outside of formal sessions, followed by therapist-patient sex.

|

Table 1. The “Classic” Progression in Sexual Boundary Violations

As we try to make sense of these horrendous situations, we can appreciate the fact that there are a number of risk factors inherent in the therapeutic relationship. Patients see us because they are at vulnerable points in their lives. These relationships with us are powerfully asymmetrical. Therapists are often able to rationalize their behaviors and assert that the patient has provided “consent.” They may adopt a “rhetoric of justification,” insisting that the abuse was in the patient's best interest, citing the “illusion of improvement” by pointing out that the patient “felt better.” Unfortunately, for some patients, there is a reciprocal endeavor to “help” the therapist.

Needless to say, therapists who commit boundary violations usually have serious personal problems and may have psychiatric diagnoses. Commonly found are major mood disorders, substance abuse disorders, sexual disorders, and a variety of personality disorders including narcissistic, borderline, or psychopathic. Boundary violations may occur at times of increased personal vulnerability for therapists such as bereavement, separation, mental disorders, job stress, and financial problems.

TWO GENERAL “TYPES”

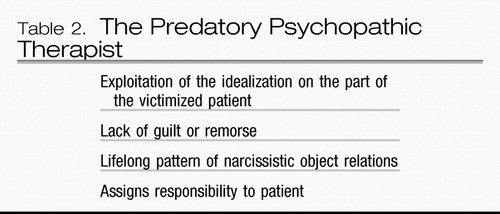

Although each case is unique, a number of general “types” of violators have been described (17). I will focus on two. The first is the predatory psychopathic violator (Table 2). These individuals are characterized by their exploitation of the idealization inherent in intensive psychotherapy, with a complete lack of any guilt or remorse, and a propensity to glibly assign responsibility to the abused patient.

|

Table 2. The Predatory Psychopathic Therapist

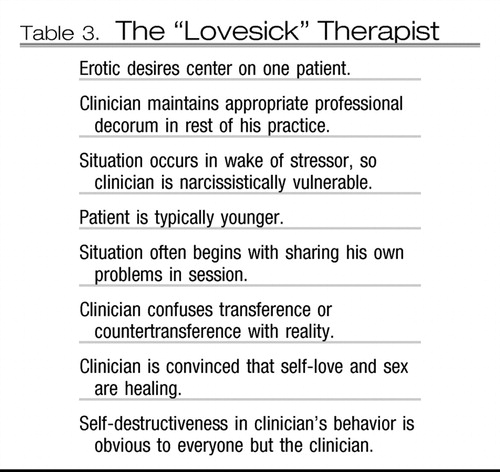

The second general type described is the “lovesick” therapist (Table 3). Unlike the predatory violator, with these therapists erotic desire centers on one patient only. The violations generally occur in the wake of major stressors, often marital disruptions, so the therapist is narcissistically vulnerable. These therapists convince themselves that they are truly and deeply “in love” and that these feelings are not a result of transference. The self-destructiveness is obvious to everyone except the therapist.

|

Table 3. The “Lovesick” Therapist

OUR LEGACY FROM THE PIONEERS

Gabbard (4) pointed out that the concept of appropriate professional boundaries is relatively recent and still evolving. Freud and his early disciples indulged in a good deal of trial and error as they evolved psychoanalytic technique, and some committed what would be seen today as serious violations. These early boundary violations may contribute to our current difficulties. What was not acknowledged but was ignored or rationalized by the pioneering generation of analysts may have become scotomatized in their professional progeny.

Sigmund Freud, Sandor Ferenczi, and C. G. Jung are arguably the three “biggest” pioneers of psychoanalysis, and Donald W. Winnicott is one of the most prominent of recent contributors. Despite their preeminence, each of these may have contributed to this legacy. I will outline a number of incidents involving these four monumental contributors demonstrating problematic behaviors regarding boundaries. I wish to make it clear at the outset that these vignettes all derive from documented, published sources. However, please keep in mind that there may also be alternate accounts.

JUNG, SPIELREIN, AND FREUD

C. G. Jung had an intense affair with Sabrina Spielrein, his first psychoanalytic “control” case (18). Unwilling to divorce his wealthy wife, Jung attempted to break off the affair. Spielrein was furious and is said to have physically attacked Jung. Spielrein remained enraged with Jung. She contacted Freud and visited him in 1909. She revealed to Freud her involvement with Jung, presumably knowing that this would give Freud “ammunition” in his skirmishes with Jung, with whom he was in a serious power struggle. Jung, a most formidable adversary, may have countered with charges of Freud's alleged affair with his sister-in-law, Minna Bernays.

FERENCZI, ELMA AND GIZELLA PALOS, AND FREUD

Sandor Ferenczi had sexual involvements with both members of a mother/daughter patient pair, Gizella and Elma Palos, respectively (4). Ferenczi persuaded Freud to treat Elma, and Freud provided reports to Ferenczi about Elma. Freud also wrote to Gizella about Ferenczi. Ferenczi did eventually take Elma back into analysis and then married Gizella in 1919. Freud had also been the analyst of Ferenczi, and he made clear his feeling to Ferenczi that Gizella was his preferred choice for marriage. It is interesting to note that in their correspondence Freud at times addressed Ferenczi as “Dear Son.”

FREUD, LOE KAHN, AND ERNST JONES

Loe Kahn, the common-law wife of Ernest Jones, later Freud's biographer, was Freud's analysand (4, 19). Freud reported to Jones regarding his treatment of Loe. Freud viewed Jones as sexually impulsive, perhaps even exploitative. He had actively discouraged a relationship between Jones and his daughter, Anna. Freud subsequently steered Kahn away from Ernest Jones and toward Herbert Jones (no relation). Sandor Ferenczi was the analyst of Ernest Jones and Freud and Ferenczi discussed Jones.

FREUD, FRINK, AND BIJUR

A particularly problematic set of boundary violations apparently occurred during Sigmund Freud's treatment of the American psychiatrist, Horace Frink (4, 20). Freud apparently made interpretations of Frink's alleged latent homosexuality a focus of the analysis. Frink also discussed with Freud his treatment of Angelika Bijur, a wealthy heiress and the wife of a wealthy man. Freud suggested that Frink should divorce his wife and marry Bijur, in part to assure himself and Freud that he was not a latent homosexual. Freud apparently thought that Bijur might contribute to certain psychoanalytic causes. Bijur's husband was so outraged by Frink's behavior that he wrote to Freud, threatening to take out a full-page ad in the New York Times denouncing Frink and psychoanalysis. Frink did marry Bijur, but the marriage was an abysmal failure, and Frink subsequently made several suicide attempts.

In at least some of these instances one can appreciate the possibility that these pioneers considered themselves to be acting in accordance with a sense of knowing what was best for the patient or for some other greater cause. This sense of entitlement to act on someone else's behalf, for their best interest, may well be part of these pioneers' legacy.

MASUD KHAN, WAYNE GODLEY, AND DONALD W. WINNICOTT

A relatively recent, well-publicized case involved the high profile London psychoanalyst, Masud Khan (21, 22). The case was further complicated by Khan's involvement with his training analyst, Donald W. Winnicott, arguably one of a handful of the most creative analysts of more recent times (23). Wayne Godley was referred to Khan by Winnicott. There were major intrusions into the analysis by Khan from the first session. Khan secretly invited Godley's wife for a consultation and also set up meetings a trois with him, Godley, and a female patient of his. Khan stated they were “handmade for one another.” Godley was apparently invited on a number of occasions to Khan's home where he witnessed Khan and his wife getting drunk and often engaging in spectacular fights. Khan, Godley, and their wives at times attended social functions together where Khan demonstrated to Godley his acquaintance with major celebrities. Godley, in a moving description of his travails with Khan, delineated how he reenacted a compulsion to “save” a “drunken, collapsing” father (24). Some observers considered that a significant element here was the failure of Winnicott to deal with Khan's problematic anger because Winnicott needed Khan to oversee and edit his writings (23). Khan apparently served as Winnicott's personal editor throughout the years of his analysis of Godley. Khan reportedly was involved in numerous other boundary violations (25).

ADDITIONAL RECENT EXAMPLES

One recent case, which received a great deal of press coverage, involved Margaret Bean-Bayog, a former Harvard psychiatrist, and a university medical student (26). This case involved an intense transference relationship and the use of regressive techniques. However, Bean-Bayog stopped seeing the student when she was in the process of adopting a child and the patient, who could not handle the separation, committed suicide.

Sexual boundaries are not the only ones crossed in damaging ways. Two other cases with significant publicity included financial matters and personal power. George Pollock, a former leader in organized psychiatry treated a patient, who then left the bulk of her $5M estate to a research organization administered by Dr. Pollack (27). She also established large personal trusts for Pollack and his family. Her son, unhappy with these arrangements, charged that Pollock had “brainwashed” his mother. That case was settled out-of-court. Another variation on the allure of finances occurred with the case of Robert Willis, a psychiatrist who treated the wife of a major financial executive (27). The patient had mentioned in treatment two financial moves being readied by her husband. Upon hearing this, Willis quickly bought stock in the companies in “play.” Willis' trading on insider information came to light, and he was fined and then sued.

Another very special group of “boundary challenges” are those associated with “celebrity” patients for whom therapists may suddenly acquire a willingness to bend or cross boundaries (27). As with the “lovesick” therapist, the violation may be limited to these patients only. Celebrity patients can give the therapist a powerful perception of enhanced stature. There are also seductive gratifications associated with accepting the idealization of a well-known individual. In addition, there may be potential monetary benefits, both to the individual practitioner and to the profession. It can be very tempting both to charge these individuals higher fees and to seek their contributions to various psychoanalytically related causes.

WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT BOUNDARY VIOLATIONS?

I suspect that a certain number of boundary violations are inherent in our profession and perhaps in all other “helping” professions as well. If so, we need to focus our efforts on dealing with the consequences and on preventing any further damage from occurring.

Our profession, both individually and institutionally, has an inconsistent record of responding (or not responding) to boundary violations (28–30). This situation may be related in part to our “legacy” from our forebears. Local ethics committees, often because of some very “real” relationships involving colleagues and the accused and because of confidentiality, may genuinely be ill equipped to deal with at least some errant practitioners. Professional organizations also fear retaliation from accused practitioners. External consultation involving both individuals and organizations may have some potential to balance the needs of the clinician, the local organization, and the victimized patient.

One obvious question is what is the role of supervision in preventing or at least decreasing violations? Although their track record is modest at best, supervisors can help their supervisees understand the reasons for maintaining firm boundaries even when a therapist is under pressure to be “more human.” A supervisor can also help in defining for a trainee the nature of the therapeutic alliance, and, importantly, the limits of a therapeutic relationship. A supervisor can also help a trainee think through just whose interest is best served by various interventions during therapy. A supervisor can also focus on the importance of maintaining the therapist's neutrality and on the different styles of interaction with the patient. Nearly every trainee at some time must confront the issue of how to deal with relatively minor boundary crossings such as gifts and other materials brought to therapy sessions. In today's psychotherapeutic world supervision is probably utilized considerably less than in the past. It is probably more useful to think in terms of consultation, whether for one or for multiple sessions. Consultation should be considered when one notes any evidence of the progression identified earlier or when one's colleagues might point out any manifestations of such changes in behavior. Obviously many vulnerable practitioners will have difficulty listening to and accepting such input. Certainly if one is in a position with some administrative authority over an apparently vulnerable practitioner, consultation can be recommended.

There are widely differing reactions to and sanctions against therapists who become involved in serious boundary violations, from an empathic approach based on understanding with an effort for rehabilitation (30, 31) to an approach more generally used with sex offenders (32). A controversial area is the willingness to provide rehabilitation for victims and for certain of the colleagues. One prominent practitioner attempts reparative work by consulting with both the abuser and the abused patient (30). Although it is doubtful that we can provide primary intervention, we should be willing to work vigorously to enforce our ethical standards. Another much neglected area is the need to assure that the victims of boundary violations receive appropriate aid.

In conclusion, with the interventions currently available to us, we have, at best, a modest record. Courts, licensing boards, and national professional societies are very important means of intervention, particularly with the more serious violations of a predatory nature. Another focus is on education, from the beginning of our professional training and extending throughout our careers. Most important, I believe, is the willingness to be involved by as many frontline members of our profession as possible. This involvement sends a clear message that we take this issue seriously but also includes unglamorous work such as serving on committees, hearing ethics cases, serving on impairment committees, and being available to serve on task forces to refine and enforce ethical standards. Admittedly, our efforts have not shown particularly promising results, nor have we been especially effective in identifying potential violators and excluding them before they become therapists. We must also be firm in maintaining a professional posture that ethical standards exist for sound reasons and that those standards override the personal conviction of knowing what is best for a patient.

1 Davies JM: Love in the afternoon: a relational reconstruction of desire and dread in the countertransference. Psychonal Dial, 1994; 4: 153– 170Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Davies JM: Whose bad object are we anyway? Repetition and our elusive love affairs with evil. Psychonal Dial, 2004; 14: 711– 732Google Scholar

3 Gabbard GO, Pelz ML: Speaking the unspeakable: institutional reactions to boundary violations by training analysts. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2001; 49: 659– 673Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Gabbard GO: The early history of boundary violations in psychoanalysis. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2001; 43: 1115– 1136Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Akamatsu TJ: Intimate relationships with former clients: national survey of attitudes and behavior among practitioners. Prof Psychol Res Pract 1988; 19: 454– 458Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Borys DS, Pope KS: Dual relationships between therapist and client: a national study of psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers. Prof Psychol Res Pract 1989; 20: 283– 293Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Garrett T: Sexual contact between clinical psychologists and their patients: qualitative data. Clin Psychol Psychother 1986; 1999; 6: 54– 62Google Scholar

8 Gartrell N, Herman J, Olarte S, Feldstein M, Localio R: Psychiatrist-patient sexual contact: results of a national survey. 1: prevalence. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143: 1126– 1131Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Gechtman L: Sexual contact between social workers and their clients, in Sexual Exploitation in Professional Relationships. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1989, pp 27– 38Google Scholar

10 Holroyd JC, Brodsky AM: Psychologists' attitudes and practices regarding erotic and nonerotic physical contact with patients. Am Psychologist 1977; 32: 843– 849Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Margison F: Boundary violations and psychotherapy. Curr Opin Psychiatry 1996; 9: 204– 208Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Pope KS, Levenson FI: Schover, LR. Sexual intimacy in psychology training: results and implications of a national survey. Am Psychologist 1979; 34: 682– 689Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Pope KS, Kerth-Spiegel P, Tabachnick BG: Sexual attraction to clients: the human therapist and the (sometimes) inhuman training system. Am Psychologist 1986; 41: 147– 158Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Pope KS, Tabachnick BG, Keith-Spiegel P: Ethics of practice: the beliefs and behaviors of psychologists as therapists. Am Psychologist 1987; 42: 993– 1006Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Bajit TR, Pope KS: Therapist-patient sexual intimacy involving children and adolescents. Am Psychologist 1989; 44: 45 5Google Scholar

16 Simon RI: Therapist patient sex: from boundary violations to sexual misconduct. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22: 31– 47Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Gabbard GO: Sexual misconduct, in Review of Psychiatry, vol 13. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 433– 456Google Scholar

18 Kerr J: A Most Dangerous Method: the Story of Jung, Freud, and Sabina Spielrein. New York, Vintage Books, 1993Google Scholar

19 Maddox B: Freud's Wizard: Ernest Jones and The Transformation of Psychoanalysis. Cambridge, MA, Da Capo Press, 2007Google Scholar

20 Warner S: Freud's analysis of Horace Frink, M.D. a previously unexplained therapeutic disaster. J Am Acad Psychoanal 1994; 22: 137– 152Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Boynton RS: The return of the repressed: the strange case of Masud Khan. Boston Rev Dec 2002/Jan 2003Google Scholar

22 Hopkins LB: How Masud Khan fell into psychoanalysis. Am Imago 2005; 61: 483– 494Crossref, Google Scholar

23 McCarthy JB: Disillusionment and devaluation in Winnicott's analysis of Masud Khan. Am J Psychol 2003; 63: 81– 92Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Godley W: Saving Masud Khan. London Rev Books 2001; 23: 4Google Scholar

25 Limentani AM: M. Masud R. Khan (1924–1989). Int J Psychoanal 1992; 73: 155– 159Google Scholar

26 McNamara E: Breakdown: Sex, Suicide and the Harvard Psychiatrist. New York, Pocket Books, 1994Google Scholar

27 Farber S, Green M: Hollywood on the Couch: a Candid Look at the Love Affair between Psychiatrists and Moviemakers. New York, Morrow, 1993Google Scholar

28 Celenza A, Gabbard GO: Analysts who commit sexual boundary violations: a lost cause? J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2003; 51: 817– 836Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Margolis M: Analyst-patient sexual involvement, clinical experiences and institutional response. Psychoanal Inquiry 1977; 17: 349– 370Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Margolis M: Incest, erotic countertransference and analyst—analysand boundary violations. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1994; 42: 985– 989Google Scholar

31 Gabbard GO, Lester EP: Boundaries and Boundary Violations in Psychoanalysis, New York, Basic Books, 1995Google Scholar

32 Pilgrim D, Guinan P: From mitigation to culpability: rethinking the evidence about therapist sexual abuse. Eur J Psychother Couns Health 1999; 2: 153– 168Crossref, Google Scholar