Is ADHD a Risk Factor for Psychoactive Substance Use Disorders? Finding From a Four-Year Prospective Follow-Up Study

Abstract

Objective. To evaluate whether attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders (PSUD), attending to issues of psychiatric comorbidity, family history, and adversity. Method. Using assessments from multiple domains, the authors examined 140 ADHD and 120 normal control subjects at baseline and 4 years later. Drug and alcohol abuse and dependence were operationally defined. Results. No differences were detected in the rates of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence or in the rates of abuse of individual substances between the groups; both ADHD and control probands had a 15% rate of PSUD. Conduct and bipolar disorders predicted PSUD, independently of ADHD status. Family history of substance dependence and antisocial disorders was associated with PSUD in controls but less clearly so in ADHD probands. Family history of ADHD was not associated with risk for PSUD. ADHD probands had a significantly shorter time period between the onsets of abuse and dependence compared with controls (1.2 years versus 3 years, p<.01). Conclusions. Adolescents with and without ADHD had a similar risk for PSUD that was mediated by conduct and bipolar disorder. Since the risk for PSUD has been shown to be elevated in adults with ADHD when compared with controls, a sharp increase in PSUD is to be expected in grown-up ADHD children during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Psychoactive substance use disorders (PSUD) are among the most feared outcomes for children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Yet, whether ADHD is an independent risk factor for PSUD remains a source of controversy. Although most studies report that grown-up ADHD children are at greater risk for PSUD than controls, the differences between groups are small and not statistically significant in most studies (Barkley et al., 1990; Borland and Heckman, 1976; Gittelman et al., 1985; Hechtman and Weiss, 1986; Howell et al., 1985; Klinteberg et al., 1993; Loney et al., 1981a; Mannuzza et al., 1991b, 1993; Weiss et al., 1979). In addition, interpretation of the findings is complicated by small samples in some studies and the absence of operational definitions of PSUD in others.

Moreover, the existing literature on ADHD and PSUD suggests that the ADHD child’s risk for PSUD is mediated by comorbid conduct disorder and is not a direct complication of ADHD (Babor et al., 1992; Barkley et al., 1990; Biederman et al., 1995c; Borland and Heckman, 1976; Gittelman et al., 1985; Hechtman and Weiss, 1986; Howell et al., 1985; Klinteberg et al., 1993; Loney et al., 1981b; Mannuzza et al., 1991a; Weiss et al., 1979). For example, August et al. (1983) showed that the risk for DSM-III alcohol or drug abuse in ADHD children at a 4-year follow-up assessment was entirely accounted for by comorbid conduct disorder at baseline. Similar findings were reported by Barkley et al. (1990).

However, an important issue relevant to the prediction of PSUD in children with ADHD is that psychiatric comorbidity in ADHD is not limited to conduct disorder; it extends to mood and anxiety disorders as well (Biederman et al., 1991). Since these latter disorders also increase the risk for PSUD in pediatric (Bukstein et al., 1989) and adult subjects (Regier et al., 1990; Rounsaville et al., 1991a), they could mediate the risk for PSUD in children with ADHD. Thus, the association between ADHD and PSUD needs to be reexamined in a manner that accounts for co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders.

Along with psychiatric comorbidity, family-genetic risk factors may also be important contributors to the risk for PSUD in ADHD children. Family-genetic, twin, and adoption studies provide consistent evidence suggestive of a genetic component to both ADHD (Biederman et al., 1992) and PSUD (Cloninger, 1987; Luthar et al., 1993; Merikangas et al., 1985). Other risk factors that have also been associated with the development of PSUD in youth include poor relations with parents, family disruption, and low IQ (Bry et al., 1982; Newcomb et al., 1986). Thus, family history of ADHD, PSUD, or antisocial disorders and environmental adversity may enhance the risk for PSUD in children who have ADHD.

Whether ADHD or its associated disorders are risk factors for PSUD has clear clinical and public health relevance. Considering that the emergence of PSUD is a serious complication in the course of ADHD, its early identification could allow interventions that would prevent the disorder from becoming chronic and incapacitating. A thorough understanding of the antecedents of PSUD in children with ADHD could help to develop appropriate prevention programs aimed at those children at very high risk for PSUD. Prevention programs aimed at diminishing risk factors for PSUD in children with ADHD are particularly important because ADHD is a highly prevalent disorder that is acquired in childhood many years before the onset of PSUD. In light of the enormous cost and uncertain outcome of ADHD treatment, prevention programs have significant public health relevance.

In this article, we report data from a 4-year longitudinal study of children and adolescents with DSM-III-R ADHD. Our goal was to examine prospectively the antecedents and correlates of PSUD at a 4-year follow-up, attending to issues of familiality, adversity, and comorbidity. Based on prior work, we hypothesized that psychiatric comorbidity, familiality, and adversity would be risk factors for PSUD in children with ADHD.

Method

We analyzed data from a family-genetic study of ADHD that we have presented in previous publications (Biederman et al., 1996b). The original sample included a total of 260 children (140 ADHD and 120 normal control subjects) chosen from psychiatric and nonpsychiatric settings (Biederman et al., 1992). These groups had 454 and 368 first-degree biological relatives, respectively. We obtained informed consent for all subjects prior to their enrollment in the protocol. All index children were Caucasian, non-Hispanic males between the ages of 6 and 17 years. We selected ADHD children who had been referred by psychiatrists or pediatricians and non-ADHD healthy (normal) control subjects. At the 4-year follow-up, 91% of the 140 ADHD children and 91% of the 120 normal controls seen at baseline were successfully recruited. The rates of successful follow-up at 4 years did not differ between groups. There were no significant differences between subjects successfully followed up and those lost to follow-up on any of the measures used in this study.

The index children and their siblings were assessed at baseline and then again 4 years later. Parents were examined at baseline only. All diagnostic assessments used DSM-III-R-based structured interviews. Psychiatric assessments of children relied on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E). Diagnoses were based on independent interviews with the mothers and direct interviews of children, except for those younger than 12 years of age, who were not directly interviewed. Diagnostic assessments of parents were based on direct interviews with each parent, using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. To assess childhood diagnoses in the parents, we administered unmodified modules from the K-SADS-E. At baseline and the 1-year follow-up, the structured interviews assessed lifetime history of psychopathology; at year 4, these assessments reflected the interval since the prior assessment. The assessment personnel were blind to the index child diagnosis (ADHD or control) and ascertainment site (psychiatric or pediatric). All follow-up assessments were made blind to prior assessments of the same subjects and their family members.

The interviewers had undergraduate degrees in psychology and were trained to high levels of interrater reliability. We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having three experienced, board-certified child and adult psychiatrists diagnose subjects from audio-taped interviews done by the assessment staff. Based on 173 interviews, the median kappa value was .86.

A committee of board-certified child and adult psychiatrists chaired by the senior author (J.B.) resolved all diagnostic uncertainties. The committee members were blind to the subjects’ ascertainment group, ascertainment site, all data collected from other family members, and all nondiagnostic data. Diagnoses were considered positive if, based on the interview results, DSM-III-R criteria were unequivocally met to a clinically meaningful degree. We diagnosed major depression only if the depressive episode was associated with marked impairment. Since the anxiety disorders comprise many syndromes with a wide range of severity, we used two or more anxiety disorders to indicate the presence of a clinically meaningful anxiety syndrome. For children older than 12 years, the diagnosticians combined data from direct and indirect interviews by considering a diagnostic criterion positive if it was endorsed in either interview. Alcohol or drug abuse or dependence was diagnosed according to DSM-III-R criteria.

In addition to psychiatric data, we assessed the following: (1) cognitive functioning using subtests from the Wechsler intelligence tests, the Wide Range Achievement Test Revised (WRAT-R), and the Gilmore Oral Reading test (interviewers were trained to administer these tests and supervised throughout the study by a child clinical psychologist with extensive experience in the psychological assessment of children); (2) social functioning with the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale of the DSM-III-R; and (3) socioeconomic status and family intactness (divorce or separation of parents in family of origin). School dysfunction was assessed by documenting repeated grades, placement in special classes, or need for tutoring. These assessments were identical for baseline and follow-up assessments with one exception: the Gilmore Oral Reading test assessed reading ability at baseline and the reading subtest of the WRAT-R was used at follow-up. All cognitive, school, and psychosocial assessments at follow-up were blind to baseline data collected on the same subjects.

Using the methods of Sattler (1988), we estimated Full Scale IQ from the Vocabulary and Block Design subtests and computed the Freedom From Distractibility IQ from the other subtests. All of our analyses of the Wechsler subtests used age-corrected scaled scores. The definition of learning disabilities under Public Law 94-142 requires a significant discrepancy between a child’s potential and achievement. We used the regression procedure recommended by Reynolds (1984) to define the discrepancy score.

Psychosocial adversity was assessed using the following: (1) the proportion of the child’s life exposed to maternal and paternal psychopathology, (2) socioeconomic status, (3) family intactness (divorce or separation of parents), (4) an Index of Family Conflict (Biederman et al., 1995b), and (5) Rutter’s Index of Adversity (Biederman et al., 1995a). The summary Index of Family Conflict used the Moos Family Environment Scales. Rutter’s indicators of adversity were low social class, large family size, paternal criminality, maternal mental disorder, and severe marital discord. The summary index of family conflict was used as a proxy for severe marital discord by using the median in the normal control population as the cutoff point. Our operational definitions of Rutter’s indicators were added together to create a total index of family adversity.

Because of the large number of comparisons, statistical significance was determined at the p=.01 level in order to reduce the number of type I errors.

Results

ADHD and control children were of similar age at both baseline (10.6±3.0 years versus 11.5±3.6 years, not significant [NS]) and follow-up (14.4±3.1 versus 15.2±3.7 years, NS) and had a similar history of broken homes at both assessments (34% versus 23%, NS). However, at baseline and follow-up, respectively, both ADHD + PSUD (13.7±1.5 and 17.8±4.5) and controls + PSUD (15.5±1.6 and 19.4±1.7) were significantly older than ADHD (10.0±2.9 and 13.9±2.9) and control (10.8±3.4 and 14.5±3.5) probands without PSUD (p<.01 for baseline and follow-up findings). In addition, ADHD + PSUD probands were significantly younger than control + PSUD probands at both baseline (13.7±1.5 versus 15.5±1.6, p<.01) and follow-up (17.8±4.5 versus 19.4±1.7, p<.01).

Examination of specific rates of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence failed to identify meaningful differences between ADHD subjects and controls. Thus, to minimize the number of statistical tests, the broader category of PSUD that included drug or alcohol abuse or dependence was used as the dependent variable. PSUD was identified in 14.8% of ADHD probands and 15.5% of controls (NS). Subsequently, findings were compared among four groups of probands: (1) ADHD probands with PSUD (ADHD + PSUD); (2) ADHD probands without PSUD (ADHD); (3) controls with PSUD (control + PSUD); and (4) controls without PSUD (controls).

Ages of onset of substance use in both groups were also compared. No statistically significant differences were detected in comparisons between ADHD + PSUD versus controls + PSUD in age at onset of PSUD (14.8±1.6 versus 15.3±2.2, NS) or its subtypes, alcohol abuse (15.2±2.5 versus 15.5±2.7, NS), alcohol dependence (15.2±1.6 versus 16.7±2.0, NS), drug abuse (16.2±2.1 versus 17.8±2.5, NS), and drug dependence (15.2±1.3 versus 15.0±1.6, NS). However, ADHD children had an earlier age of onset than controls in almost all categories of abuse and dependence. Similarly, there were no significant differences in the preferred drugs of abuse by ADHD + PSUD or controls + PSUD. The drug most frequently abused in both groups was marijuana (n=13, 100% versus n=8, 100%), followed by hallucinogens (n=3, 23% versus n=3, 38%, NS), stimulants (n=0, 0% versus n=1, 13%, NS), cocaine (n=1, 8% versus n=0, 0%, NS), and nitrous (n=0, 0% versus n=1, 13%, NS).

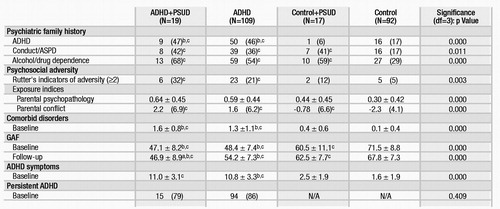

ADHD + PSUD and ADHD probands had indistinguishable rates of familial ADHD that were significantly greater than the rates in controls. In contrast, family history of antisocial disorders and substance dependence were similarly elevated in ADHD + PSUD, ADHD, and controls + PSUD probands; all three groups differed significantly from controls without PSUD in the rates of these family histories (Table 1).

Both ADHD proband groups had significantly higher exposure-to-adversity risk factors than controls. Indices of exposure to parental psychopathology and exposure to parental conflict were more severe in ADHD + PSUD, ADHD, and controls + PSUD than in controls (Table 1). ADHD + PSUD, ADHD, and controls + PSUD also had worse scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale than did controls. We did not find meaningful differences between ADHD + PSUD and ADHD probands in the mean number of ADHD symptoms, mean number of comorbid disorders, or number of ADHD probands with persistent ADHD (Table 1).

Psychiatric antecedents of PSUD

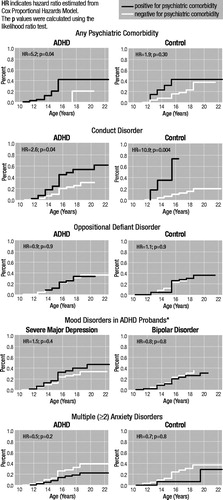

Figure 1 depicts hazard ratios examining associations between comorbid psychiatric disorders at baseline and PSUD at follow-up in ADHD probands and controls. The figure shows that conduct disorder was a significant predictor of PSUD in both ADHD and control probands. In contrast, oppositional defiant, anxiety, and mood disorders were not. (The risk associated with mood disorders could only be examined in ADHD probands since these disorders had a very low prevalence in controls).

Correlates and progression of PSUD

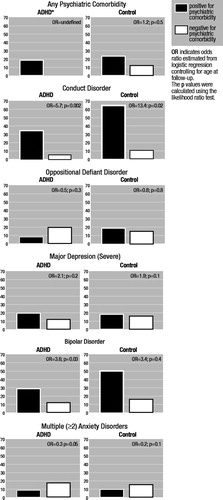

Examination of concurrent correlates of PSUD at follow-up revealed significant associations between PSUD and conduct disorder in both ADHD and control probands. Although for bipolar disorder the magnitude of the association was almost identical for ADHD and controls, statistical significance could only be documented for ADHD probands, most likely because of limited statistical power. In contrast, no meaningful associations were detected between PSUD and oppositional defiant disorder, major depression, or anxiety disorders (Figure 2).

We examined whether cognitive characteristics of probands were associated with PSUD. At both assessments, these analyses failed to identify any meaningful association between IQ, rates of learning disability, freedom from distractibility IQ, or learning disability and PSUD in either ADHD or control probands.

To evaluate whether ADHD status conferred an increased risk for rapid progression from abuse to dependence, we also examined the duration from the onset of abuse to that of dependence. We found that ADHD probands had a significantly shorter gap between abuse and dependence than did controls (1.2 years versus 3 years, p<.01).

Discussion

Using cross-sectional and 4-year longitudinal data, we reevaluated the association between ADHD and PSUD in a large sample of well-characterized ADHD and demographically matched non-ADHD comparison boys. These groups did not differ in rates of PSUD or in the rates of individual substances of abuse. Although conduct and bipolar disorders were associated with PSUD, these associations were independent of ADHD. Family history of substance dependence and antisocial disorders was associated with PSUD in controls but less clearly so in ADHD probands. Family history of ADHD was not associated with risk for PSUD in ADHD probands.

The rates of PSUD observed in our sample of referred ADHD and control probands (15% in both) are similar to those found in other studies in which PSUD had been operationally defined. For example, August et al. (1983) reported rates of 15% in 14-year-old hyperactive probands. Gittelman et al. (1985) and Mannuzza et al. (1991a,b) found rates of PSUD of 22% and 18% in two independent samples of hyperactive subjects compared with rates of 18% and 13% in matched controls. Loney (1981b) reported rates of 27% in 22-year-old hyperactive youths and in 18% of their nonhyperactive brothers. Weiss et al. (1979) reported rates of 15% in 19-year-old hyperactive subjects and in 11% of controls. In each of these reports, rates of PSUD did not significantly differ between ADHD and control subjects. The only studies that reported significant differences between ADHD and control subjects were two studies reporting on rates of substance use but not abuse or dependence (Howell et al., 1985; Klinteberg et al., 1993).

Also consistent with previous findings in the literature was the association of PSUD with conduct disorder. This association was not limited to children with ADHD, indicating that it is independent of ADHD. In the absence of conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder did not predict PSUD. This latter finding confirms prior reports that oppositional defiant disorder does not share with conduct disorder the same severe correlates and outcomes (Biederman et al., 1996d).

In addition to conduct disorder, we also found an association between PSUD and bipolar disorder in both ADHD and control subjects. Although the diagnosis of juvenile mania remains controversial, converging evidence from case reports, case series (Biederman et al., 1996a; Wozniak et al., 1995a), and family studies (Wozniak et al., 1995b) supports the validity of this diagnosis in juveniles. Notably, an association between PSUD and bipolar disorder has also been reported in clinical and epidemiological studies of drug- and alcohol-dependent adolescents and adults (Bukstein et al., 1989; DeMilio, 1989; Kaminer, 1991; Regier et al., 1990; Ross et al., 1988; Rounsaville et al., 1982, 1991b). In combination, these findings indicate that juvenile mania may be a risk factor for adolescent-onset PSUD. However, unlike the association between PSUD and conduct disorder, the association between PSUD and bipolar disorder was only observed at follow-up. If confirmed, this finding would indicate that bipolar disorder may be more proximally associated with the onset of PSUD than is conduct disorder.

In contrast to the associations between conduct and bipolar disorders with PSUD, we found no meaningful link between PSUD and nonbipolar major depression or anxiety disorders. Such associations have been reported in clinical and epidemiological studies of drug- and alcohol-dependent adolescents and adults (Bukstein et al., 1989; DeMilio, 1989; Kaminer, 1991; Regier et al., 1990; Ross et al., 1988; Rounsaville et al., 1982, 1991b). The reasons for these seemingly discrepant findings are unclear. However, our subjects are still passing through the age of risk for mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders, and it is possible that the disorders will develop at a later age.

The current prospective results are strikingly consistent with our previously reported retrospective findings from a sample of adults with childhood-onset ADHD (Biederman et al., 1995c). That study found that childhood-onset conduct disorder and juvenile bipolar disorder conferred a significantly increased risk for PSUD; anxiety and depression were weak predictors of PSUD. However, in contrast to the 15% rate of PSUD observed in our adolescent sample, the adult study documented a much higher rate (52% versus 27% for ADHD and controls, respectively). Thus, although at a mean age of 15 years, our adolescent ADHD sample shows no elevated risk for PSUD, the data from our adult sample suggest that differences should emerge in late adolescence and early adulthood. Based on retrospective reports, at the age of 15, the rate of PSUD in the adult sample was only 13% (Wilens et al., unpublished). This finding is consistent with the 15% rate found in our prospective study of children.

In our adult sample, there was a marked increase in the rates of PSUD during the late adolescent and young adult years. Our analyses showed that these onsets could be attributed to ADHD independently of conduct or bipolar disorders. These results suggest that over time, an acceleration in the rates of PSUD can be expected in both ADHD and control subjects, with a greater acceleration in those with ADHD. A key finding in adults with ADHD was that conduct and bipolar disorders were associated with a risk for adolescent-onset PSUD, whereas ADHD without comorbidity was associated with onset in young adulthood. These retrospective results will require confirmation in the present prospective study with a longer follow-up period.

We found no differences between ADHD subjects and non-ADHD comparison children in the preferred drugs of abuse. In both ADHD and comparison children with a drug use disorder, marijuana was the most common drug of abuse, followed distantly by stimulants and cocaine. This finding is consistent with work by Gittelman et al. (1985) in which elevated rates of marijuana abuse were found with persistent ADHD symptoms. Reciprocally, the addiction literature shows no preferential use of stimulants in individuals with PSUD and comorbid ADHD (Carroll and Rounsaville, 1993; Eyre et al., 1982; Weiss et al., 1988; Wilens et al., 1994). Taken together, these results are inconsistent with the commonly held view that individuals with ADHD abuse stimulants preferentially.

Although drug experimentation is ubiquitous among youth, the majority of youth who engage in drug or alcohol use do not escalate their involvement to abuse or dependence (Glantz and Pickens, 1992b). This implies that there are important differences between those who make the transition from use to abuse and those who do not. In this regard, it is notable that we found adolescents with ADHD to have a significantly shorter transition time from abuse to dependence; it is possible that children with ADHD represent a group at high risk for rapid escalation to PSUD. Since ADHD is present prior to the child’s involvement with drugs, this implies that effective drug abuse prevention is possible through early identification and appropriate intervention in high-risk ADHD children (Glantz and Pickens, 1992a).

Despite heavy documentation that psychosocial adversity factors put youth at risk for PSUD (Brook et al., 1992), we did not find compelling evidence in this regard. It remains to be seen whether clearer associations between psychosocial adversity and PSUD will emerge over time as the sample matures and the rates of PSUD rise.

Although previous research suggests associations between low IQ and PSUD (Clayton, 1992), we failed to observe that trend in our sample of ADHD and control children. Despite the absence of associations between cognitive deficits and PSUD in our sample, a recent report documented that heavy marijuana use is associated with cognitive deficits in college-age youth (Pope and Todd-Yurgelun, 1996). Considering that marijuana seems to be the preferred drug of abuse in ADHD subjects (Biederman et al., 1995c), longer follow-up with careful cognitive monitoring is warranted.

Our work has several clinical implications. Parents of ADHD children frequently seek to know the long-term prognosis of their child’s condition. Our data and the other studies we cited suggest that ADHD children with conduct disorder are at risk for adolescent-onset PSUD and should be closely monitored for drug use. Close monitoring of ADHD children without conduct disorder may not be warranted in early adolescence, but more data are needed to be certain about their risks in late adolescence and adulthood.

Naturally, our results must be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations. The lack of direct psychiatric interviews with children younger than 12 may have decreased the sensitivity of some diagnoses, especially “internalizing” disorders such as anxiety and depression. However, we did find high rates of both of these disorders in our study. Also, children younger than 12 have limited expressive and receptive language abilities; they cannot easily sequence events in time, and they have difficulties with abstraction. Although our results are likely to generalize to many of the ADHD children seen in pediatric and psychiatric settings, we do not know whether our results will generalize to ADHD children in the wider population.

Another limitation of our design is that we did not control for treatment. Since ours was a clinical sample, many of our subjects were receiving some form of treatment during the follow-up period. However, it is unlikely that treatment effects accounted for our results. Elsewhere, we reported no significant associations between persistence or remission of ADHD and intensity of treatment (Biederman et al., 1996c). Moreover, rates of counseling and use of psychotropics were highly prevalent in ADHD children with and without conduct disorder. Thus, differential therapeutic attention to children with conduct disorder cannot explain the observed link between conduct disorder and PSUD (Biederman et al., 1996c).

Despite these limitations, our prospective findings indicate that conduct and bipolar disorders were prominent risk factors for adolescent-onset PSUD independent of ADHD status. Although the risk for PSUD in children with ADHD was indistinguishable from the risk in controls, ADHD probands had a significantly shorter gap between abuse and dependence than did controls. This suggests that children with ADHD may be at higher risk for early-onset addictions than controls. In light of findings documenting that the risk for PSUD is significantly increased in ADHD adults compared with gender- and age-matched non-ADHD controls, a sharp increase in PSUD is to be expected in ADHD children during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

|

Table 1. Baseline and Follow-Up Onset of PSUD in ADHD and Control Probands: Characteristics of Sample

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves of Onset of Psychoactive Substance Use Disorders in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Control Probands Stratified by Psychiatric Comorbidity

*Hazard ratios could not be estimated for controls due to groups with no subjects.

Figure 2. Risk of Psychoactive Substance Use Disorders (PSUD) Associated With 4-Year Cumulative History of Psychiatric Comorbidity

*No ADHD subjects free from other psychiatric disorders were found to have PSUD. ADHD=attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

1 August GJ, Stewart MA, Holmes CS (1983), A four-year follow-up of hyperactive boys with and without conduct disorder. Br J Psychiatry 143:192–198.Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Babor TF, Hofmann M, DelBoca FK, et al. (1992), Types of alcoholics, I. Evidence for an empirically derived typology based on indicators of vulnerability and severity. Arch Gen Pychiatry 49:599.Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L (1990), The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29:546–557.Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E, et al. (1996a), Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and juvenile mania: an overlooked comorbidity? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:997–1008.Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, et al. (1996b), A prospective four-year follow-up study of attention deficit hyperactivity and related disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53:437–446.Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, et al. (1996c), Predictors of persistence and remission of ADHD into adolescence: results from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:343–351.Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, et al. (1992), Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives in psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:728–738.Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Biederman J, Faraone SV, Milberger S, et al. (1996d), Is childhood oppositional defiant disorder a precursor to adolescent conduct disorder? Findings from a four-year follow-up study of children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:1193–1204.Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone S, et al. (1995a), Family-environment risk factors for ADHD: a test of Rutter’s indicators of adversity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:464–470.Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone S, et al. (1995b), Impact of adversity on functioning and comorbidity in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:1495–1504.Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S (1991), Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. Am J Psychiatry 148:564–577.Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Milberger S, Spencer T, Faraone S (1995c), Psychoactive substance use disorder in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry 152:1652–1658.Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Borland BL, Heckman HK (1976), Hyperactive boys and their brothers: a 25-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 33:669–675.Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Brook J, Cohen P, Whiteman M, Gordon A (1992), Psychosocial risk factors in the transition from moderate to heavy use or abuse of drugs. In: Vulnerability to Drug Abuse, Glantz M, Pickens R. eds. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp 359–388.Google Scholar

15 Bry B, McKeon P, Pandina R (1982), Extent of drug use as a function of a number of risk factors. J Abnorm Psychol 91:273–279.Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Bukstein OG, Brent DA, Kaminer Y (1989), Comorbidity of substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 146:1131–1141.Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Carroll K, Rounsaville B (1993), History and significance of childhood attention deficit disorder in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Compr Psychiatry 34:75–82.Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Clayton R (1992), Transitions in drug use: risk and protective factors. In: Vulnerability to Drug Abuse, Glantz M, Pickens R, eds. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp 15–52.Google Scholar

19 Cloninger CR (1987), Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science 236:410–416.Crossref, Google Scholar

20 DeMilio L (1989), Psychiatric syndromes in adolescent substance abusers. Am J Psychiatry 146:1212–1214.Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Eyre S, Rounsaville B, Kleber H (1982), History of childhood hyperactivity in a clinical population of opiate addicts. J Nerv Ment Dis 170:522–529.Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Gittelman R, Mannuzza S, Shenker R, Bonagura N (1985), Hyperactive boys almost grown up: I. Psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42:937–947.Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Glantz M, Pickens R, eds (1992a), Vulnerability to Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.Google Scholar

24 Glantz M, Pickens R (1992b), Vulnerability to drug abuse: introduction and overview. In: Vulnerability to Drug Abuse, Glantz M, Pickens R, eds. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp 1–15.Google Scholar

25 Hechtman L, Weiss G (1986), Controlled prospective fifteen year follow-up of hyperactives as adults: non-medical drug and alcohol use and anti-social behaviour. Can J Psychiatry 31:557–567.Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Howell D, Huessy H, Hassuk B (1985), Fifteen-year follow-up of a behavioral history of attention deficit disorder. Pediatrics 76:185–190.Google Scholar

27 Kaminer Y (1991), The magnitude of concurrent psychiatric disorders in hospitalized substance abusing adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 22:89–95.Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Klinteberg B, Andersson T, Magnusson D, Stattin H (1993), Hyperactive behavior in childhood as related to subsequent alcohol problems and violent offending: a longitudinal study of male subjects. Person Indiv Diff 15:381–388.Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Loney J, Kramer J, Milich RS (1981a), The hyperactive child grows up: predictors of symptoms, delinquency and achievement at follow-up. In: Psychosocial Aspects of Drug Treatment for Hyperactivity, Gadow KD, Loney J, eds. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp 381–416.Google Scholar

30 Loney J, Whaley-Klahn MA, Kosier T, Conboy J (1981b), Hyperactive boys and their brothers at 21: predictions of aggressive and antisocial outcomes. Presented at the Meeting of the Society for Life History Research, Monterey, CA.Google Scholar

31 Luthar S, Ball S, Rounsaville B (1993), Psychiatric disorders among relatives of cocaine-abusing individuals. Am J Addict 2:225–231.Google Scholar

32 Mannuzza S, Gittelman-Klein R, Addalli KA (1991a), Young adult mental status of hyperactive boys and their brothers: a prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30:743–751.Google Scholar

33 Mannuzza S, Gittelman Klein R, Bonagura N, Malloy P, Giampino TL, Addalli KA (1991b), Hyperactive boys almost grown up: V. Replication of psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:77–83.Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M (1993), Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:565–576.Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Merikangas K, Weissman M, Prusoff B, Pauls D, Leckman J (1985), Depressives with secondary alcoholism: psychiatric disorders in offspring. J Stud Alcohol 46:199–204.Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Newcomb DR, Maddahian E, Bentler PM (1986), Risk factors for drug use among adolescents: concurrent and longitudinal analyses. Am J Public Health 76:525–531.Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Pope H, Todd-Yurgelun D (1996), The residual cognitive effects of heavy marijuana use in college students. JAMA 275:521–527.Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. (1990), Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 264:2511–2518.Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Reynolds CR (1984), Critical measurement issues in learning disabilities. J Spec Educ 18:451–476.Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Ross HE, Glaser FB, Germanson T (1988), The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alcohol and other drug problems. Arch Gen Psychiatry 45:1023–1032.Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Rounsaville B, Anton S, Carroll K, Budde D, Prusoff B, Gawin F (1991a), Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:43–51.Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Rounsaville B, Weissman M, Kleber H, Wilber C (1982), Heterogeneity of psychiatric diagnosis in treated opiate addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39:161–166.Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Weissman MM, et al. (1991b), Psychiatric disorders in relatives of probands with opiate addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:33–42.Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Sattler JM (1988), Assessment of Children’s Intelligence. San Diego: Jerome M Sattler.Google Scholar

45 Weiss G, Hechtman L, Perlman T, Hopkins J, Wener A (1979), Hyperactives as young adults: a controlled prospective ten-year follow-up of 75 children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 36:675–681.Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Weiss RD, Mirin SM, Griffin ML, Michael JL (1988), Psychopathology in cocaine abusers. J Nerv Ment Disord 176:719–725.Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Wilens T, Biederman J, Spencer T, Frances R (1994), Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity and psychoactive substance use disorders. Hosp Immunity Psychiatry 45:421–435.Google Scholar

48 Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K, et al. (1995a), Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:867–876.Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Wozniak J, Biederman J, Mundy E, Mennin D, Faraone SV (1995b), A pilot family study of childhood-onset mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:1577–1583.Crossref, Google Scholar