Comprehensive Analysis of Remission (COMPARE) with Venlafaxine versus SSRIs

Abstract

Background:

To compare venlafaxine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram) in the treatment of depression.

Methods and Materials:

Meta-analysis of 34 randomized, double-blind studies identified by a worldwide search of all research sponsored by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals through January 2007. Patients were treated with venlafaxine (n = 4191; mean dose 151 mg/day) or SSRIs (n = 3621); nine studies also included a placebo control group (n = 932). The primary outcome measure was intent-to-treat (ITT) remission rates (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression ≤7) at week 8.

Results:

The overall difference in ITT remission rates was 5.9% favoring venlafaxine (95% confidence interval [CI]: .038–.081; p < .001). Based on this difference, the number needed to treat (NNT) to benefit is 17 (95% CI: 12–26). In the nine placebo controlled studies, the drug-placebo differences were 6% (.02–.09) for the SSRIs and 13% (.09–.16) for venlafaxine. For the specific SSRIs, the difference versus fluoxetine (mean dose = 37 mg/day; 20 studies) was significant (6.6% [95% CI: .030–.095]); smaller differences versus paroxetine (mean dose = 25 mg/day; eight studies; 5%), sertraline (mean dose = 127 mg/day; three studies; 3%), and citalopram (mean dose = 38 mg/day; two studies; 4%) were not significant. Attrition rates due to adverse events were higher with venlafaxine than with SSRI therapy, 11% and 9% respectively (p = .0011).

Conclusions:

These results indicate that venlafaxine therapy is statistically superior to SSRIs as a class, but only to fluoxetine individually. The clinical significance of this modest advantage seems limited for the broad grouping of major depressive disorder. Nonetheless, an NNT of 17 may be of public health relevance given the large number of patients treated for depression and the significant burden of illness associated with this disorder.

(Reprinted with permission from Biological Psychiatry 2008; 63:424–434)

It has long been believed that all antidepressants approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are similarly effective (1, 2). However, because contemporary randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of antidepressants yield relatively small drug-placebo difference (3, 4), few if any individual studies of modern antidepressants have had sufficient power to discriminate between an effective treatment and a potentially more effective one (5). Moreover, the frequency of type II errors, coupled with a second problem, publication bias (i.e., the tendency for research sponsors only to publish the results of studies with favorable outcomes), has complicated critical evaluation of comparative antidepressant efficacy based solely on published studies.

When individual RCTs do not yield definitive results, statistical methods that synthesize data from a number of studies can be used to compare antidepressants (6). Meta-analyses were used to establish that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were as effective as, and better tolerated than, the previous standard, the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (7, 8). Meta-analyses also detected differences in subgroup comparisons that were not apparent in qualitative reviews. For example, significant differences favoring the tertiary amine TCAs clomipramine and amitriptyline were found in meta-analyses of studies of hospitalized or severely depressed patients (7, 9), possibly through their dual inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake (10).

Venlafaxine is a dual serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) that has been widely studied. Meta-analyses using either studies (11) or pooled individual patient data (12, 13) as the unit of observation have suggested that venlafaxine may have an efficacy advantage compared with SSRIs. These reports have been subject to criticism, however, and relatively few of the individual studies found significant differences.

The purpose of this report is to extend the findings of these meta-analyses using two approaches. Meta-analysis was performed on an all-inclusive set of Wyeth-sponsored, double-blind RCTs comparing venlafaxine and an SSRI. The meta-analysis was limited to Wyeth-sponsored studies because of the necessity for individual patient data. However, to evaluate further the differential effects of these treatments and to explore the reliability of various methods of analysis, a second meta-analysis incorporating all available data regardless of sponsor and an assessment of selection bias was conducted and displayed using a funnel plot.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Design

Individual patient data were obtained from all studies completed by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals comparing venlafaxine and an SSRI (circa January 2007). For inclusion, we required that studies employ randomization, double-blind treatment, and evaluation with a standard dependent measure, such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) (14). In addition, studies had to enroll patients meeting criteria for major depressive disorder, as determined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (edition III-R or IV) or International Disease Classification-10 criteria (15). An extensive search of the research activities of all divisions and affiliates of Wyeth Pharmaceuticals worldwide identified 34 such studies (16–43). Only 16 of the studies have been published in their entirety; 11 have been presented at scientific congresses or published as abstracts, and results of the remaining 7 studies have not been presented or published. Eight of these studies (S211, S360, S367, S372, S340, S347, S348, S349), representing less than 25% of the total patient group, were included in earlier analyses of pooled individual patient data (12, 13).

Most of the trials used standard exclusion criteria such as the presence of a primary Axis I disorder other than depression, severe Axis II pathology (by investigator's discretion), history of any significant medical disorder, and a history of drug or alcohol abuse for at least 6 months before entering the study. Most studies excluded patients with a history of nonresponse to either venlafaxine or the particular comparator SSRI being studied. With the exception of one study that enrolled patients who had not responded to two antidepressant trials in the current depressive episode (37), all of the studies required that patients be off antidepressants for at least 2 weeks before study participation.

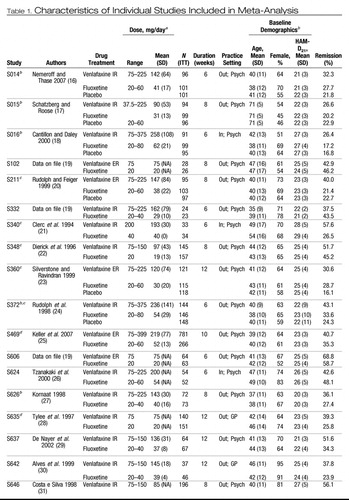

The studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, including written informed consent. Table 1 summarizes the individual design characteristics of the 34 studies (16–43). Twenty studies used venlafaxine immediate release (IR); 14 studies used venlafaxine extended release (ER). The SSRI comparators were fluoxetine (20 studies), paroxetine (8 studies), sertraline (3 studies), citalopram (2 studies), and fluvoxamine (1 study). Nine studies also included a placebo control group.

|

|

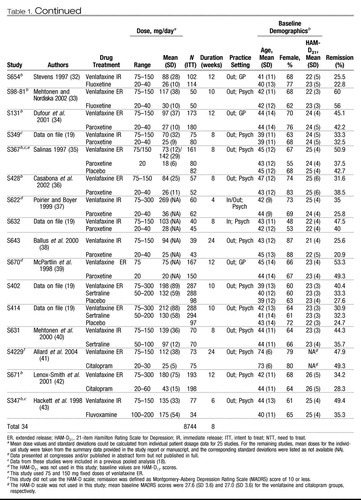

Table 1. Characteristics of Individual Studies Included in Meta-Analysis

Because the inclusion criteria we chose for our analysis necessitated that studies be double-blind randomized trials and that original patient data be available, we recognized that a number of studies could potentially be excluded as a result. As such, we conducted a funnel plot analysis to extend the primary data set by including all available (as of January 2007) studies in the public domain, regardless of sponsor, and by broadening the inclusion criteria to include studies that were open-label, provided that patients were randomized to the treatment groups. Published studies were identified via a literature search. Unpublished studies that have been presented at the scientific meetings of the American Psychiatric Association, American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, World Congress of Biological Psychiatry, Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum also were reviewed. To our knowledge, all randomized controlled trials comparing venlafaxine to an SSRI for treatment of depression were included. In addition, the first author wrote the sponsor or corresponding author of all studies not included in the Wyeth data set and, when feasible, obtained remission rates using the same uniform criteria (HAM-D17 score of 7 or less at week 8 using the last observation carried forward [LOCF] method).

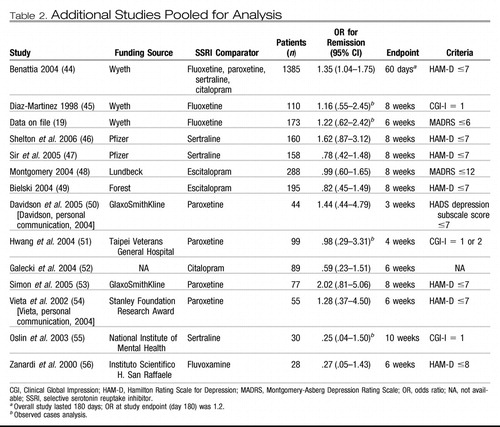

Fourteen additional studies comparing venlafaxine/venlafaxine ER to SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, or sertraline) were identified and included in this analysis: 3 Wyeth-sponsored studies previously excluded because of open-label design and 11 RCTs conducted by other organizations (Table 2) (44–56). One additional independently sponsored study was not included because neither response nor remission data were available (57).

|

Table 2. Additional Studies Pooled for Analysis

Study groups

The study groups had a mean age of 42 years (range: 17–88). The female to male ratio was approximately 2:1, and 7% of the participants were inpatients. Most patients presented with moderate to severe depression, with a mean pretreatment HAM-D21 scores of 23.6 (SD = 4.25), 23.7 (SD = 4.25), and 23.3 (SD = 3.67) for the venlafaxine, SSRI, and placebo groups, respectively (see Table 1).

Study drugs

Patients in each study were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with venlafaxine (n = 4191; IR, n = 1653; ER, n = 2538) or an SSRI (n = 3621). The SSRIs included fluoxetine (n = 1970), paroxetine (n = 692), sertraline (n = 652), citalopram (n = 273), and fluvoxamine (n = 34). Mean doses were computed at study endpoint (Table 1), with the LOCF) method used to account for dropouts. For studies longer than 8 weeks, the last observed dose at the 8-week time point was used. Weighted means with treatment group size as their weight were used to compute the overall grand mean for the data set.

Efficacy and safety assessments

In the meta-analysis, the intent to treat (ITT) study group included all patients randomly assigned to treatment who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one on-therapy efficacy assessment. The studies ranged in length from 4 to 24 weeks. Because only 14 studies extended beyond 8 weeks of therapy, week 8 was chosen a priori as the primary endpoint. For patients who did not complete 8 weeks of therapy, the LOCF method was used (i.e., the last efficacy evaluation was counted for all subsequent time points). The primary efficacy outcome was remission, defined as a HAM-D17 total score of 7 or less. For the one study that did not use the HAM-D, a Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score of 10 or less was used to define remission.

To compare results across studies by using funnel plot analysis, we used a standardized measure of efficacy, the odds ratio (OR) for remission with venlafaxine versus SSRIs, at one consistent time point. For those studies in which individual patient data were available, remission was defined as a HAM-D17 total score of 7 or less, and efficacy analyses were performed on the ITT population using the last observation carried forward method to account for missing data. Because the majority of studies did not extend beyond 8 weeks, this time point was chosen as the primary endpoint. For those studies in which individual patient data were not available, summary data from the published articles and abstracts were used to compute an OR for remission using the most stringent definition provided. If available, week 8 data were used; if not, the study endpoint was used.

For each individual study, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed, and a combined effect size was estimated using fixed- and random-effect models (with the former reported given absence of statistically significant heterogeneity) for the overall data sets and for each individual SSRI. Funnel plot analysis was used to detect the presence of selection bias using the trim and fill method (58), the linear regression test (59), and the rank correlation test (60).

Safety and tolerability in the individual studies were evaluated on the basis of adverse events recorded throughout the study period and changes in physical examination, vital signs, and clinical laboratory findings before and after acute-phase treatment. Study 469 data were included in the analysis of discontinuation rates. However, adverse event data for week 8 were not available.

Statistical methods

Validity of combining studies.

Statistical tests for heterogeneity (61) were used to assess whether it was valid to combine the effect sizes within groups of studies with similar, but not identical, designs.

Primary efficacy analyses.

Remission rate differences at week 8 were used as effect sizes, with 95% confidence intervals computed based on Mantel-Haenszel fixed- and random-effects models (61). The number needed to treat (NNT) to benefit (62), the effect size widely used in evidence-based medicine (63), also was computed.

Tolerability analyses.

For this report, descriptive statistics on discontinuation rates and treatment-emergent adverse event rates were calculated from available data sources (i.e., clinical study reports, published manuscripts or abstracts, posters, and SAS tables).

RESULTS

Tests for heterogeneity (61) revealed no statistically significant differences, indicating that the effect sizes from the individual studies could be combined. Overall, 8877 patients were randomly assigned to treatment, of which 8744 (98.5%) were included in the ITT analyses. There were 4191 patients treated with venlafaxine and 3621 treated with SSRIs. The groups did not differ in the proportion of randomized subjects not included in the ITT/LOCF analysis. Mean daily doses were as follows for the combined data set: venlafaxine 151 mg/day; fluoxetine 37 mg/ day; paroxetine 25 mg/day; sertraline 127 mg/day; citalopram 38 mg/day; and fluvoxamine 175 mg/day.

Efficacy analyses

Remission rate differences (and 95% CIs) for the individual studies and the combined data sets are presented in Figure 1. Remission rate differences for the individual studies ranged from −7% to 31%; differences numerically favored venlafaxine over SSRIs in 28 studies, with 6 studies numerically favoring the SSRI over venlafaxine. Overall, venlafaxine therapy was associated with a 5.9% (95% CI: .038–.081) advantage. Remission rate differences for venlafaxine compared with each specific SSRI ranged from 3.4% to 14.1% (Figure 1). Only the results versus fluoxetine (remission rate difference = 6.6% [95% CI: .030–.095; p < .0011 based on 20 studies) were statistically significant.

Remission is defined as 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) score of 7 or less for 33 of the 34 studies. One study (4229) did not use the HAM-D scale, and remission was defined as a Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale score of 10 or less. Remission rate differences for the individual studies ranged from −7% to 31%; differences numerically favored venlafaxine in 27 studies (although only 5 reached statistical significance), with 6 studies numerically favoring the SSRIs.

Figure 2 demonstrates that the results did not differ significantly depending on the use of the IR or ER formulation of venlafaxine or whether the patient population included inpatients or outpatients. Results of the sensitivity analyses indicated that the venlafaxine-SSRI difference was not dependent on any one particular study or study characteristic (data available from authors on request). For example, a similar difference favored venlafaxine over the SSRIs in the nine placebo-controlled studies (see Figure 3). With respect to drug versus placebo differences, there was a 6% (95% CI: .02–.09) advantage favoring SSRIs versus placebo and 13% (95% CI: .09–.16) advantage favoring venlafaxine versus placebo. The magnitude of the drug versus placebo difference (i.e., 13% vs. 6%) also was significantly greater for venlafaxine compared with SSRIs (p < .001).

N = number of studies; VEN = vanlafaxine; ER = extended-release; IR = immediate-release.1) One study (4229) did not use the HAM-D scale, and remission was defined as a Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale score of 10 or less. ER, extended-release; IR, immediate-release; VEN, venlafaxine.

ER, extended-release; IR,immediate-release; VEN, venlafaxine.

Updated meta-analysis: studies by all sponsors

The funnel plot analysis was based on 48 studies, including 14 additional studies, 11 of which were not funded by Wyeth. No evidence of statistically significant selection bias was observed in the updated analysis of 48 studies, suggesting that study sponsorship did not significantly influence outcomes. The estimated difference in remission rates in this expanded set of studies was 5.3% favoring venlafaxine, which was almost identical to the results of the primary analysis (see Figure 4). This difference was again statistically significant, with an OR of 1.25 (95% CI: 1.16–1.36, p < .001).

Overall adjusted effect odds ratio was 1.26 (95% confidence interval: 1.16–1.38). The funnel plot trim and fill method identifies excess statistical outliers on either side and “fills” the opposite side with theoretical studies accordingly to balance the funnel. An adjusted weighted effect size is then calculated from the revised plot. No evidence of statistically significant selection bias was detected with the linear regression test (z = −.19, p = .42) and rank correlation test (z = .05, p = .48) (58).

Discontinuation and tolerability analyses

Overall discontinuation rates for any reason were 28% for the pooled venlafaxine and 27% for the pooled SSRI therapy groups. A higher percentage (11%) of venlafaxine-treated patients discontinued therapy because of adverse events compared with SSRIs (9%; p = .0011). Discontinuation rates because of lack of efficacy were 4% for venlafaxine and 5% for SSRIs.

The five most common treatment-emergent adverse events in both active treatment groups were nausea, headache, dry mouth, insomnia, and diarrhea (individual data available from authors on request). The incidences of nausea (33% vs. 26%) and headache (26% vs. 17%) were higher for venlafaxine, and the incidence of diarrhea was higher for the SSRIs (19% vs. 11%).

DISCUSSION

This study presents the largest and most comprehensive evaluation of the relative efficacy of a specific antidepressant ever undertaken: the outcomes of nearly 8000 patients treated in double-blind RCTs comparing venlafaxine and SSRIs were studied, using an all-inclusive set of the 34 eligible RCTs conducted by Wyeth. Although the results of this meta-analysis largely confirm earlier findings from smaller data sets, results also qualify conclusions about the relative efficacy of venlafaxine versus the SSRIs as a class. Specifically, the magnitude of the advantage favoring venlafaxine reported herein was smaller than reported in the initial meta-analysis of patient data from the first eight double-blind trials (i.e., 6% vs. 10%) (12), and statistical significance was somewhat dependent on the larger number of studies using fluoxetine as the SSRI comparator.

On the basis of the data presented here, the NNT to benefit was 17 (95% CI: 12–26) compared with the NNT = 10 calculated from earlier analyses. Furthermore, with respect to specific SSRIs, we were only able to confirm a statistically significant effect versus fluoxetine. Thus the advantage for venlafaxine was relatively small versus the SSRIs as a class and the issue of efficacy versus SSRIs other than fluoxetine remains in doubt.

To address the generalizability of the findings of the primary analysis, which was necessarily limited to the studies conducted by Wyeth (for which the data from each individual patient were available), a second more conventional meta-analysis was performed that included studies that were not by Wyeth. Importantly, this analysis helped to ascertain whether the results of the studies that were conducted by the manufacturer of venlafaxine were in some way biased or not representative of the results of more “neutral”RCTs or studies conducted by the manufacturers of various SSRIs. As illustrated by the funnel plot analysis of the full set of 48 studies, there was no evidence of study selection bias (i.e., the plot clearly conformed to the shape of an inverted funnel).

Several reasons can be proposed to explain why the significant difference in efficacy observed with venlafaxine versus fluoxetine was not seen in comparisons with other individual SSRIs. First, the number of patients involved in the 20 studies comparing venlafaxine and fluoxetine accounted for 58% of all patients receiving venlafaxine and 54% of those receiving SSRIs leading to an increased probability of detecting moderate differences between treatment groups. Another possibility is that patients involved in the trials comparing venlafaxine and fluoxetine were typically not as sick at baseline. In 8 of 20 studies with fluoxetine, the mean HAM-D21 scores were 22 or less compared with only 1 of the 14 studies involving other comparators. Although higher levels of pretreatment depressive symptoms have been found to be significantly associated with greater response to antidepressant therapy, making detection of small differences over placebo easier (64), the situation may be different in considering remission rates. Specifically, patients who are more depressed at baseline may be less likely to be in remission at the end of the study (65). To assess this possibility, various definitions of response derived from the HAM-D17, HAM-D21, Clinical Global Impression, and MADRS were com pared. Results were consistent with the primary outcome of remission as reported here, and thus probably do not explain the differences observed between venlafaxine and individual SSRIs.

Clinical significance of findings

The focus of meta-analysis is the estimation of an effect size. In a large set of studies such as this one, “statistically significant” results may reflect differences that are so small, they would not have meaningful clinical implications. For this reason, we chose remission rates, the most rigorous measure of antidepressant efficacy, as the primary efficacy outcome and focused on the comparison of remission rates across studies and study characteristics. Research conducted from epidemiologic, naturalistic, and controlled paradigms consistently document that remission of major depressive disorder is the optimal outcome of acutephase therapy, in terms of restoration of social and vocational functioning (66, 67) and reduction of longer-term risks of relapse and recurrence (68–70). As can be seen in Figure 1, the pooled effect size across all comparisons of venlafaxine versus SSRIs reflected an average difference in remission rates of 5.9%, which reflected a NNT of 17 (1/.059), that is, one would expect to treat approximately 17 patients with venlafaxine to see one more success than if all had been treated with another SSRI. Although this difference was reliable and would be important if applied to populations of depressed patients, it is also true that it is modest and might not be noticed by busy clinicians in everyday practice. Nonetheless, an NNT of 17 may be of public health relevance given the large number of patients treated for depression and the significant burden of illness associated with this disorder.

A comparison of placebo-subtracted remission rates for venlafaxine and the SSRIs is one gauge of the clinical significance of the modest difference in efficacy observed. With this approach, the magnitude of the advantage of the SSRI versus placebo can be used to define the “assay sensitivity”of the meta-analysis. Looking at the nine placebo-controlled studies, the absolute difference in remission rates between venlafaxine and placebo treatment (i.e., 13% [95% CI: .09–.16]) was significantly greater than between SSRIs and placebo (i.e., 6% [95% CI: .02–.09]) (venlafaxine vs. SSRIs: 13% vs. 6%; p < .001). To achieve one remission more than with placebo, 8 patients would need to be treated with venlafaxine (NNT = 8 [95% CI: 6–11]) compared with 18 patients who would need to be treated with an SSRI (NNT = 18 [95% CI: 11–50]). From this perspective, the magnitude of the advantage of SSRIs versus placebo in the placebo-controlled data set (NNT = 18) is similar to the advantage of venlafaxine relative to SSRIs in the combined data set (NNT = 17).

Proposed Mechanism Underlying the Observed Efficacy Advantage

The dual reuptake inhibition hypothesis posits that antidepressants that directly affect both serotonin and norepinephrine neurotransmission may have more robust efficacy than those with selective action at the serotonin transporter (SERT) (9, 12, 71–75). Greater benefit similarly may be obtained by combining norepinephrine- and serotonin-selective medications (10). However, it is important to note that this hypothesis is merely an explanatory construct, and several issues remain unclear. For example, it is not clear what dose of venlafaxine is needed to ensure that the average patient obtains a clinically meaningful level of inhibition of neuronal uptake of norepinephrine (50, 76, 77). Davidson et al. (50) found that venlafaxine ER at a dose of 225 mg per day produced more than 70% norepinephrine transporter occupancy using an ex vivo method (78), and these results have recently been confirmed (53). At the relatively low mean dose of paroxetine used in these studies, effects on norepinephrine reuptake are limited (78). It remains to be proven definitively that any efficacy advantage of venlafaxine compared with SSRIs is directly linked to its ability to inhibit the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine. It is conceivable that other neurobiological effects of venlafaxine account for these findings. However, once unfair dosing or other methodological biases are ruled out, there is no compelling alternative explanation within the models of antidepressant action as we currently understand them. It is important to determine whether the noradrenergic effects of venlafaxine are associated with the greater rate of attrition due to side effects and concerns about potential cardiovascular toxicity in overdose (50, 55, 79, 80).

Methodological considerations

One of the most important limitations of meta-analysis is the potential for bias via selective inclusion of studies. To ensure that this did not occur, the research conducted by every worldwide affiliate of Wyeth Pharmaceuticals was painstakingly searched, and no completed study of major depressive disorder was excluded if it employed random assignment and double-blind therapy. In addition, the expanded analysis that included nonWyeth-sponsored studies showed no evidence of sample bias.

Such an inclusive approach could also introduce bias; however, if the studies are too heterogenous, particularly if a large study or a particular subset of studies yields discrepant results. To this end, statistical tests for homogeneity were performed before the meta-analyses. These procedures provided some assurance that it was reasonable to combine the effect sizes from the multiple studies.

Because there is a tendency in industry-sponsored studies to use relatively low doses of comparator drugs, the possibility of bias caused by unfair or imbalanced dosing must also be considered. Because few studies permit both medications to be titrated flexibly, across the full FDA-approved dose range, it is essential to assess dose comparability. Using an approach in which the mean doses of each of the individual comparators and venlafaxine were compared with the FDA-approved range for depression, the dosages of venlafaxine and the SSRI comparators were found to be comparable overall, although we are aware that this method could be criticized on the grounds that clinicians often use doses of these antidepressants that exceed FDA guidelines and that this phenomenon may not be equal for all antidepressants.

Review of other comparative studies

With respect to studies with discrepant results, we note that the results of two small studies, one in psychotic depression (56) and the other in frail elderly nursing home residents (55), strongly favored the SSRIs (paroxetine and sertraline, respectively). In one study employing titration to maximum approved doses within 8 days (49), escitalopram (20 mg/day) therapy was much better tolerated than venlafaxine ER (225 mg/day); it was also significantly more effective among the subset of patients with higher pretreatment severity levels. In the two trials of bipolar depression to compare venlafaxine with SSRIs (54, 81), there were no significant differences in efficacy. However, patients treated with venlafaxine were more likely to experience treatment-emergent affective switches. Thus the overall advantage for venlafaxine may pertain to some specific patient groups or be evident under some conditions related to dose titration.

Limitations of this meta-analysis

Several limitations of this report warrant comment. First, because the generalizability of RCT findings to clinical practice is limited by the exclusion of patients with more complex conditions (e.g., comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders), the results of meta-analyses based on the data from RCTs are subject to the same limitation.

Second, these data come from short-term trials of antidepressant efficacy and may not extend across longer courses of therapy. Specifically, the SSRIs could “catch up”during the continuation phase of therapy.

Third, some question the validity of combining all of the SSRIs into a single group or class of antidepressants. It is commonplace to group together conceptually the SSRIs as the leading class of “first-line”antidepressant medications, and the SSRIs were routinely combined for classwise comparisons of efficacy, tolerability, and safety compared with the TCAs. However, these drugs are not interchangeable, and they have distinct pharmacologic properties. For example, considerable evidence suggests that paroxetine exhibits dose-dependent SERT and NE uptake blocking activity, although not at the doses of paroxetine employed in these studies (50, 78, 82, 83). Although this meta-analysis provides further evidence that venlafaxine is significantly more effective than the SSRIs as a class, the differences versus paroxetine, sertraline, and citalopram were not statistically significant. Moreover, in the primary analysis, there were only three studies with sertraline, two with citalopram, one of fluvoxamine, and none of escitalopram available for inclusion. The relative efficacy of venlafaxine versus SSRIs other than fluoxetine thus remains an open question.

CONCLUSION

This meta-analysis of 34 head-to-head RCTs provides further evidence that venlafaxine is statistically superior to the SSRIs as a class, although the clinical significance of this difference is unclear. It is hoped that these data will foster renewed interest in research linking presumed mechanisms of action with therapeutic effects of antidepressants.

1 Morris JB, Beck AT (1974): The efficacy of antidepressant drugs: A review of research (1958–1972). Arch Gen Psychiatry 30:667–674Crossref, Google Scholar

2 American Psychiatric Association (2000): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry 157(4 suppl):1–45.Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Khan A, Warner HA, Brown WA (2000): Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials: An analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:311–317Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M (2002): Placebo response in studies of major depression: variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA 287:1840–1847Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Thase ME (2002): Comparing the methods used to compare antidepressants. Psychopharmacol Bull 36(suppl 1):S1–S17.Google Scholar

6 Lieberman JA, Greenhouse J, Hamer RM, Krishnan KR, Nemeroff CB, Sheehan DV, et al. (2005): Comparing the effects of antidepressants: Consensus guidelines for evaluating quantitative reviews of antidepressant efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology 30:445–460Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Anderson IM, Tomenson BM (1994): The efficacy of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in depression: A meta-analysis of studies against tricyclic antidepressants. J Psychopharmacol 8:238–249Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Anderson IM (2000): Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: A meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. J Affect Disord 58:19–36Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Anderson IM (1998): SSRIS versus tricyclic antidepressants in depressed inpatients: A meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Depress Anxiety 7(suppl 1):11–17.Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Nelson JC, Mazure CM, Jatlow PI, Bowers MB Jr, Price LH (2004): Combining norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition mechanisms for treatment of depression: A double-blind, randomized study. Biol Psychiatry 55:296–300Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Einarson TR, Arikian SR, Casciano J, Doyle JJ (1999): Comparison of extended-release venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Ther 21:296–308Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RI (2001a): Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry 178:234–241Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Stahl SM, Entsuah R, Rudolph RL (2002): Comparative efficacy between venlafaxine and SSRIs: A pooled analysis of patients with depression. Biol Psychiatry 52:1166–1174Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Hamilton M (1959): The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 32:50–55Crossref, Google Scholar

15 World Health Organization (1992): International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 1989 Revision. Geneva: WHO.Google Scholar

16 Nemeroff CB, Thase ME (2007): On behalf of the EPIC 014 Study Group: A double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of venlafaxine and fluoxetine treatment in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res 41:351–359Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Schatzberg A, Roose S (2006): A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in geriatric outpatients with depression. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry 14:361–370Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Cantillon M, Daley M. Further superiority of SNRI venlafaxine over SSRI fluoxetine in major depression and melancholia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of both response and remission (wellness).

19 Data on file. Collegeville, PA: Wyeth Research.Google Scholar

20 Rudolph R, Feiger A (1999): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of once-daily venlafaxine extended release (XR) and fluoxetine for the treatment of depression. J Affect Disord 56:171–181Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Clerc GE, Ruimy P, Verdeau PJ (1994): A double-blind comparison of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in patients hospitalised for major depression and melancholia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 9:139–143Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Dierick M, Ravizza L, Realini R, Martin A (1996): A double-blind comparison of venlafaxine and fluoxetine for treatment of major depression in outpatients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 20:57–71Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Silverstone PH, Ravindran A (1999): Once-daily venlafaxine extendedrelease (XR) compared with fluoxetine in outpatients with depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 60:22–28Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Rudolph R, Aguiar L, Entsuah R, Derivan A (1998): Early onset of antidepressant activity of venlafaxine compared with placebo and fluoxetine in outpatients in a double-blind study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 8(suppl 3): Abstract P.1.027.Google Scholar

25 Keller M, Trivedi MH, Thase ME, Shelton R, Kornstein S, Nemeroff CB, et al. (2007): The prevention of recurrent episodes of depression with venlafaxine for two years (PREVENT) study: Outcomes from the acute and continuation phases. J Clin Psychiatry 68:1246–1256Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Tzanakaki M, Guazzelli M, Nimatoudis I, Zissis NP, Smeraldi E, Rizzo F (2000): Increased remission rates with venlafaxine compared with fluoxetine in hospitalised patients with major depression and melancholia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 15:29–34Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Kornaat H (1998): Randomized, double-blind comparison of venlafaxine and fluoxetine for moderately depressed outpatients. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 3(suppl 1): Abstract PMK02021.Google Scholar

28 Tylee A, Beaumont G, Bowden MW, Reynolds A (1997): A double-blind, randomized, 2-week comparison study of the safety and efficacy of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in moderate to severe depression in general practice. Prim Care Psychiatry 3:51–58Google Scholar

29 De Nayer A, Geerts S, Ruelens L, Schittecatte M, De Bleeker E, Van Eeckhoutte I (2002): Venlafaxine compared with fluoxetine in outpatients with .pb10 depression and concomitant anxiety. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 5:115–120Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Alves C, Cachola I, Brandao J (1999): Efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in outpatients with major depression. Prim Care Psychiatry 5:57–63Google Scholar

31 Costa-e-Silva J (1998): Randomised, double-blind comparison of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in outpatients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 59:352–357Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Stevens I (1997): Comparison of the efficacy and safety of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in GP patients with moderate to severe depression. Biol Psychiatry 42(suppl 1):244s [abstract 90–48].Google Scholar

33 Mehtonen O, Nordiska AB (2002): A double-blind, randomized study of the efficacy and safety of venlafaxine extended release (ER) versus fluoxetine in outpatients with major depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 12(suppl 3):S253 [abstract].Google Scholar

34 Dufour A, Van Hauteghem D, Slachmuylders P, Leyman S, Mignon A (2001): Clinical acceptability of venlafaxine extended release and paroxetine in outpatients treated for depression by general practitioners. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 11(suppl 3):S224 [abstract].Google Scholar

35 Salinas E, for the Venlafaxine XR 367 Study Group (1997): Once daily extended release (XR) venlafaxine versus paroxetine in outpatients with major depression. Biol Psychiatry 42(suppl 1):244s [abstract 90–49].Google Scholar

36 Casabona GM, Silenzi V, Guazzelli M (2002): A randomized, double blind, comparison of venlafaxine ER and paroxetine in outpatients with moderate to severe major depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 12(suppl 3):S208 [abstract].Google Scholar

37 Poirier M-F, Boyer P (1999): Venlafaxine and paroxetine in treatment-resistant depression: double-blind, randomised comparison. Br J Psychiatry 175:12–16Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Ballus C, Quiros G, De Flores T, de la Torre J, Palao D, Rojo L, et al. (2000): The efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine and paroxetine in outpatients with depressive disorders or dysthymia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 15:43–48Crossref, Google Scholar

39 McPartlin GM, Reynolds A, Anderson C, Casoy J (1998): A comparison of once-daily venlafaxine XR and paroxetine in depressed outpatients treated in general practice. Prim Care Psychiatry 4:127–132Google Scholar

40 Mehtonen O, Sogaard J, Roponen P, Behnke K (2000): Randomised, double-blind comparison of venlafaxine and sertraline in outpatients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 61:95–100Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Allard P, Gram L, Timdahl K, Behnke K, Hanson M, Sogaard J (2004): Efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine in geriatric outpatients with major depression: A double-blind, randomised 6-month comparative trial with citalopram. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19:1123–1130Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Lenox-Smith AJ, Schaeffer P, Reynolds A, Willard L (2001): A double-blind trial of venlafaxine ER vs citalopram in patients with severe depression.

43 Hackett D, Salinas E, Desmet A (1998): Efficacy and safety of venlafaxine vs fluvoxamine in outpatients with major depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 8(suppl 3): abstract 1.210.Google Scholar

44 Benattia I, Musgnung J, Graepel J (2004): Using treatment algorithms to achieve remission of depression with venlafaxine XR or SSRIs. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 7(suppl 1):S167 [abstract P01.129].Google Scholar

45 Diaz-Martinez A, Benassinni O, Ontiveros A, Gonzalez S, Salin R, Basquedano G, Martinez RA (1998): A randomized, open-label comparison of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in depressed outpatients. Clin Ther 20:467–476Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Shelton RC, Haman KL, Rapaport MH, Kiev A, Smith WT, Hirschfeld RM, et al. (2006): A randomized, double-blind, active-control study of sertraline versus venlafaxine XR in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 67:1674–1681Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Sir A, D'Souza RF, Uguz S, George T, Vahip S, Hopwood M, et al. (2005): Randomized trial of sertraline versus venlafaxine XR in major depression: efficacy and discontinuation symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 66:1312–1320Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Montgomery SA, MoHuusom AK, Bothmer J (2004): A randomised study comparing escitalopram with venlafaxine XR in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychobiology 50:57–64Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Bielski RJ, Ventura D, Chang CC (2004): A double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 65:1190–1196Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Davidson J, Watkins L, Owens M, Krulewicz S, Connor K, Carpenter D, et al. (2005): Effects of paroxetine and venlafaxine XR on heart rate variability in depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 25:480–484Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Hwang JP, Yang CH, Tsai SJ (2004): Comparison study of venlafaxine and paroxetine for the treatment of depression in elderly Chinese inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19:189–190Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Galecki P, Florkowski A, Pietras T, Kolodziejska I, Nowakowski T, Pawelczyk A, et al. (2004): Efficiency and safety of citalopram and venlafaxine in treatment of depressive disorders in elderly patients [in Polish]. Pol Merkuriusz Lek 17:621–624Google Scholar

53 Simon JS, Sheehan D, Thase M, Owens M, Krulewicz MA, Carpenter D, et al. (2005): Comparison of efficacy and tolerability of paroxetine CR versus venlafaxine XR.

54 Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Goikolea JM, Torrent C, Colom F, Benabarre A, et al. (2002): A randomized trial comparing paroxetine and venlafaxine in the treatment of bipolar depressed patients taking mood stabilizers. J Clin Psychiatry 63:508–512Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Oslin DW, Ten Have TR, Streim JE, Datto CJ, Weintraub D, DiFilippo S, et al. (2003): Probing the safety of medications in the frail elderly: Evidence from a randomized clinical trial of sertraline and venlafaxine in depressed nursing home residents. J Clin Psychiatry 64:875–882Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Zanardi R, Franchini L, Serretti A, Perez J, Smeraldi E (2000): Venlafaxine versus fluvoxamine in the treatment of delusional depression: A pilot double-blind controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 61:26–29Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Dichter GS, Tomarken AJ, Freid CM, Addington S, Shelton RC (2005): Do venlafaxine XR and paroxetine equally influence negative and positive affect? J Affect Disord 85:333–339.Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Duval S, Tweedie R (2000): Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56:455–463Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997): Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315:629–634Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994): Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50:1088–1101Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Higgins J, Thompson SG (2002): Quantifying heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Statist Med 21:1539–1558Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Cook RJ, Sackett DL (1995): The number needed to treat: A clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 310:452–454Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ (2006): Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatry 59:990–996Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Khan A, Brodhead AE, Kolts RL, Brown WA (2005): Severity of depressive symptoms and response to antidepressants and placebo in antidepressant trials. J Psychiatr Res 39:145–150Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Frank E, et al. (2006): ACNP Task Force. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:1841–1853Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Mintz J, Mintz LI, Arruda MJ, Hwang SS (1992): Treatments of depression and the functional capacity to work. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:761–768Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Zeller PJ, Paulus M, Leon AC, Maser JD, Endicott J (2000): Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:375–380Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Thase ME, Simons AD, McGeary J, Cahalane JF, Hughes C, Harden T, et al. (1992): Relapse after cognitive behavior therapy of depression: Potential implications for longer courses of treatment? Am J Psychiatry 149: 1046–1052.Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Kerr J, Barocka A (1995): Residual symptoms after partial remission: An important outcome in depression. Psychol Med 25:1171–1180Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Simon GE (2000): Long-term prognosis of depression in primary care. Bull World Health Organ 78:439–445Google Scholar

71 Thase ME, Howland RH, Friedman ES (2001b): Onset of action of selective and multi-action antidepressants. In: den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, editors. Antidepressants: Selectivity or Multiplicity? Amsterdam: Benecke, 101–116.Google Scholar

72 Danish University Antidepressant Group (1986): Citalopram: Clinical effect profile in comparison with clomipramine. A controlled multicenter study. Psychopharmacology 90:131–138Google Scholar

73 Danish University Antidepressant Group (1990): Paroxetine: A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor showing better tolerance, but weaker antidepressant effect than clomipramine in a controlled multicenter study. J Affect Disord 18:289–299Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Quitkin FM, Taylor BP, Kremer C (2001): Does mirtazapine have a more rapid onset than SSRIs? J Clin Psychiatry 62:358–361.Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Nemeroff CB, Schatzberg AF, Goldstein DJ, Detke MJ, Mallinckrodt C, Lu Y, et al. (2002): Duloxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 36:106–132.Google Scholar

76 Harvey AT, Rudolph RL, Preskorn SH (2000): Evidence of the dual action of venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:503–509Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Bitsios P, Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM (1999): Comparison of the effects of venlafaxine, paroxetine and desipramine on the pupillary light reflex in man. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 143:286–292Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Gilmor ML, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB (2002): Inhibition of norepinephrine uptake in patients with major depression treated with paroxetine. Am J Psychiatry 159:1702–1710Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Buckley NA, McManus PR (2002): Fatal toxicity of serotoninergic and other antidepressant drugs: analysis of United Kingdom mortality data. BMJ 325:1332–1333Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Whyte IM, Dawson AH, Buckley NA (2003): Relative toxicity of venlafaxine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in overdose compared to tricyclic antidepressants. QJM 96:369–374Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, et al. (2006): Risk of switch in mood polarity to hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar depression during acute and continuation trials of venlafaxine, sertraline, and bupropion as adjuncts to mood stabilizers. Am J Psychiatry 163:232–239Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Owens MJ, Knight DL, Nemeroff CB (2001): Second-generation SSRIs: Human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine. Biol Psychiatry 50:345–350Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Nemeroff CB (2004): Early-life adversity, CRF dysregulation, and vulnerability to mood and anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull 38(suppl 1):14–20.Google Scholar