Taking A Sexual History: The Adult Psychiatric Patient

THE INITIAL INTERVIEW MUST BE SENSITIVE TO CLINICAL CONTEXT

Psychiatrists meet their patients for the first time in different types of situations, and interviewing must always be appropriate to the clinical context. For example, the first assessment interview may occur during an emergency or a situation of considerable urgency.

Although a sexual history is not always relevant in emergency situations, emergency room encounters may include patients who have experienced sexual abuse, been the targets of sexual violence, or who have become depressed or anxious after discovering that they are HIV-positive or have other sexually transmitted diseases. Psychiatric emergencies are often provoked by reactions to stressful reproductive events such as unwanted pregnancy or pregnancy loss. Commonly occurring events leading to emergency psychiatric evaluation include discovery of infidelity by a previously trusted partner, spousal abuse (a major public health problem throughout the world), traumatic reactions to sexual violence and incest, psychosexual and dysphoric reactions to medical and surgical illnesses, familial conflicts about sexual orientation, psychosexual reactions to divorce, and many other situations.

We suggest that the sexual history routinely be included in assessments carried out on an elective basis as well. We emphasize that the situations we have noted above, which may be brought to the outpatient clinician's office as well as to the emergency room, for the most part do not include the sexual disorders listed in DSM-IV-TR. Although of obvious importance, the sexual disorders in the DSM occur much less frequently in psychiatric practice than do the myriad psychosexual difficulties that psychiatric patients routinely experience and must cope with and that influence and are influenced by their primary psychiatric disorders.

THE PSYCHIATRIC HISTORY SHOULD BE DEVELOPMENTAL

The sexual history provides anchoring points and guidelines for a biopsychosocial developmental perspective. There are many reasons for our belief that the psychiatric history should be informed by a perspective that includes but goes beyond the framework of the DSM. This viewpoint is at variance with that of some descriptive psychiatrists who argue that if clusters of behavior do not meet the criteria described in the DSM, then they should not be of interest to psychiatrists who engage in the treatment of patients. In our necessarily very brief summary of developmental issues, we place particular emphasis on the first one-quarter to one-third of life when mental scenarios influencing motivation, including sexual motivation, are initially constructed.

CHILDHOOD SEXUALITY AND ATTACHMENT RELATIONSHIPS

The development of a cohesive sense of self is a task of childhood. Similarly, the capacity to tolerate frustration and adaptively regulate affects is acquired (or not) during childhood. Early childhood is a sensitive phase for the development of adequate patterns of attachment (1). These may influence interpersonal relationships throughout life. The vicissitudes of these relationships, both sexual and nonsexual in turn, may influence the etiology of many psychiatric disorders (major depressive disorder, for example) and also the capacity to cope with them.

One of the most subtle and most complex, yet important, conceptual integrations that clinicians must make is to formulate the relationship between three domains of behavior—childhood attachments; the onset of painful/negative emotions including anxiety, depression, and anger; and the experience and expression of sexuality. Connecting the past to the present may seem counterintuitive to clinicians, particularly if the patient does not do so. Also counterintuitive is the conceptual connection between emotions that may seem completely unrelated to each other. Sexual desire, for example, is associated with sexual feelings that are qualitatively different from other feelings. The notion that these may be condensed with feelings of depression, anxiety, and anger, for example, in such a way as to motivate a person to engage in certain types of sexual activities may seem improbable to some practitioners. Our clinical experience, however, and that of others suggests that mental scenarios that are influenced by disordered attachment patterns and fueled by mixed emotions may be constructed during childhood. These may repetitively motivate sexual activities (particularly problematic activities) throughout life and influence the manifestations of many psychiatric disorders.

PSYCHOSEXUALITY IS NOT RESTRICTED TO EROTIC BEHAVIOR BUT INCLUDES GENDER IDENTITY, GENDER ROLE BEHAVIOR, AND FEELINGS ABOUT GENDER ADEQUACY

Gender identity emerges during childhood and remains stable in most people, including most psychiatric patients, throughout life. Only a minute percentage of the population is transgendered. This term refers to people who do not fall into the most common categories, male or female, and it has no inherent pathological connotation. The diagnostic term “gender identity disorder” presently in the DSM-IV-TR is a subject of debate within the mental health professions.

The term “gender role behavior” refers to behaviors that stereotypically are more common among one sex than the other. The term describes behaviors that occur more commonly in large groups of males and females. There is much overlap in gender role behavior when individuals are considered. Gender role behavior is influenced by prenatal sex steroid hormones and also by the reactions of people in the environment in which children grow up. Prenatal hormones appear to influence children's play patterns, beginning in early childhood, such that boys tend to prefer to play with trains, cars, and weapons and girls with dolls. Boys go on to participate more frequently than girls in rough and tumble play, although many girls and women enjoy vigorous athletic pursuits (2).

LATE CHILDHOOD: GENDER-VALUED SELF ESTEEM, SEXUAL ORIENTATION

During early and mid childhood, most interactions occur within the family. By late childhood most social activities are occurring between peers, although intrafamilial interactions continue, of course. Late childhood is also the only phase of the life cycle when peer activities tend to be gender-segregated. This simple fact has important consequences for the development of gender-valued self-esteem (3).

Gender-valued self-esteem, the sense of pride or shame at how masculine or feminine a person feels, is frequently sensitive to the reactions of same-gendered peers. Thus, throughout life men and boys may assess how masculine they feel in relation to their (imagined) assessment by other males. Girls and women may assess how feminine they feel in relation to their (imagined) assessment by other females. These same gender judgments, made internally, supplement and modify those made by the opposite sex. Failure to live up to an imagined standard for masculinity or femininity provokes shame and guilt.

The development of boys and girls, men and women, is asymmetric in many respects, and this is particularly evident in same-sexed peer behavior. Boys tend to form groups that are larger than girls' groups and more hierarchically structured. Boys of low status are often ostracized and scapegoated and become targets of bullying. Boys tend to label low-status behaviors as feminine, and also to devalue behaviors that other boys might enjoy but that are perceived as prototypically girl-like. Girls do not tend to negatively label undesirable behaviors in girls as “masculine.” The term “tomboy,” for example, does not have the negative connotation that “sissy” does.

Girls may be as cruel as boys but they are not likely to be as menacing and violent. This is an important sex difference in behavior that persists throughout the life cycle (4).

LATE CHILDHOOD AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION

Another asymmetric area of development is that of sexual orientation. Among boys, erotic imagery tends to have its onset prior to puberty. By early adolescence, most boys experience imagery that will shape their erotic desires throughout life. Girls and women are much more diverse in this respect. For example, young women may experience themselves as lesbian (this may be partly for political reasons) during college but then go on to become heterosexual after graduation. If this behavior occurs among men, it is extremely rare. In addition, women are much more likely than men to develop sexual relationships with same-sex partners in the context of intensely meaningful relationships later in life (5).

ADOLESCENCE

Many axis I disorders have their onset during adolescence (6). The experience of puberty is radically different between the two sexes and one likely reason for this is that testosterone, on the one hand, and estrogen and progesterone, on the other, have different effects. Postpubertal males have about 10 times as much testosterone in their blood as females do. Because testosterone influences sexual desire, it is likely that this hormonal difference influences different patterns of sexual behavior. Most pubertal males experience intense erotic desire, masturbate frequently and are interested in pornography. The hormonal changes of the menstrual cycle are associated with diverse psychological effects in adolescent girls. Among a subgroup, worsening of psychiatric disorders may be timed to the cycle, and others experience premenstrual dysphoria (7). Unlike males who experience peak sexual desire postpubertally, women tend to experience their most intense sexual desire later during adulthood.

Another important sex difference that is manifested during early adolescence is in the prevalence of depression, which affects twice as many females as males. There are many possible biopsychosocial reasons for this, and each has to be considered in formulating a treatment plan (8, 9).

LATE ADOLESCENCE

Late adolescence is a time of identity synthesis. The distinction between erotic behavior and self-labeling is particularly important with respect to sexual orientation. Here, the onset of sexual desire and fantasy, which often occurs during childhood, must be distinguished from the synthesis of the sense of identity. Although people may be erotically attracted to males, females, or both, society tends to provide niches for only two sexual orientations—heterosexuality and homosexuality. Because there is no social niche for someone who is bisexual, it is quite common to find an individual who is erotically attracted to and involved sexually with partners of both sexes, but labels himself or herself as “heterosexual” or “homosexual.”

The self-labeling process has particular diagnostic significance in the instance of patients with identity weakness, such as that occurring in borderline personality disorder or during adolescence when the sense of identity has not yet solidified. Although patients with identity weakness may feel confused about their sexual desires, there is no evidence that bisexuality itself produces or is associated with any type of psychiatric disorder.

ADULTHOOD

Because of space limitations we direct attention to only a few topics. By adulthood, many patients already have major psychiatric disorders, and others develop then. The temporal overlap between the adaptive tasks of the life cycle—finding a career, marriage, and childbearing—with serious psychopathology requires no explication here. Patients who have major psychiatric disorders and are parents frequently experience impairment in parenting performance. This may be signaled by aberrant sexual behavior of children. Sexual abuse is common during childhood and adolescence and tends to be more so among disorganized families whose caretakers have serous psychopathology (10). Even when difficulties such as sexual abuse or abnormal sexual behavior in children are not present, however, many parents who are psychiatric patients have questions about their children's psychosexual development and can profit from the clinician's interest and educational efforts in this area.

LATE ADULTHOOD

As men age, they experience gradual diminution of sexual desire. However men have no experience equivalent to menopause in women. Although most women negotiate the psychohormonal changes of this life phase adaptively, perimenopause is a time when depressive symptoms in particular tend to increase. Some perimenopausal women do become depressed and require psychiatric assistance at this time (11).

Although sexuality tends to be somewhat influenced by the aging process, as are most other psychological functions, it tends to be a core part of the quality of life for most people well into the geriatric phase of development (12). This sometimes astonishes young physicians who struggle to accept fully that patients old enough to be their parents and grandparents retain an interest in sex.

CLINICAL ILLUSTRATIONS

We illustrate the kinds of behavior we have discussed here with compressed clinical examples from our educational and clinical experience. The cases have been disguised.

Maria was abandoned by her parents at age 2 and grew up in the care of three foster families. Now 19 years old, she has chronic dysthymia and intermittently uses cocaine. She has had many sexual liaisons with men and women but has never had a sexual relationship lasting for more than a few weeks. Although she is HIV-negative, she admits that she often does not use condoms. “Why bother?”

Tom is a 23-year-old part-time college student who came out as gay to his parents when he was 17 years old. Fundamentalist Christians, the parents insisted that he participate in a church-based conversion program to make him heterosexual. When his sexual orientation did not change, his parents rejected him. Tom now has a major depressive episode and alcohol abuse.

Belle, a 35-year-old married woman, sought consultation for depression. Never having seen a mental health professional before, she did so now at the insistence of her husband who threatened to leave her because she refused to participate in sexual activity. The couple had not had sexual intercourse for 9 months. With great difficulty, Belle confided that between the ages of 10 and 15 she had a sexual relationship with an uncle, her mother's beloved older brother. She had seen him 9 months earlier at her mother's funeral. She had never discussed the incest with anyone before.

Mrs. L is an 85-year-old widow, living in a nursing home. She has Alzheimer's disease, but her cognitive impairment is mild. Recently Mrs. L and a male resident have developed a romantic relationship. They hold hands in the TV room and spend time together in her room with the door closed. Mrs. L told her daughter that she and her “boyfriend” “make out … and more.” The daughter complained to the administration that her mother was “being taken advantage of.”

A 50-year-old woman with a psychotic depression was hospitalized after she attempted to hang herself. She was found to have delusions that rats were gnawing on her uterus.

These are few of countless examples of psychosexual behavior that is an integral part of the profile of psychiatric patients. Each example illustrates the need for a developmental biopsychosocial perspective with attention to the sexual aspects of the patient's difficulties. For example, the self-destructive sexual behavior of the first patient, Maria, must be understood in the context of an attachment disorder whose roots are in childhood. The second patient's depression cannot be treated with medication alone, although the immediate depressive symptoms may respond favorably to it. The origins of this man's loneliness and his need for a positive self-image should be part of the assessment and treatment. The elderly woman's relationship with her daughter and their conflicting values about the mother's sexuality must be assessed, not only her signs of dementia. The psychosexual history of the delusional woman is of obvious importance, especially since not all severely depressed people have delusions about their reproductive organs.

PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS

We began this article by emphasizing the importance of context in interviewing people about their psychosexual experiences. Context is, of course, influenced by the age of the patient, and each life phase has its own psychosocial “shape.” A general guideline is that the patient should be interviewed alone (in addition to interviews of significant others when indicated). The sexual knowledge of adolescents is often shaky, and the clinician should never assume sexual knowledge without confirming it. For example, many people, not only teenagers, do not clearly understand the definition of “risky sex.” It is helpful for the clinician to consider that psychoeducation in the area of sexuality may be necessary for many people throughout the course of treatment.

Context also informs where to start in taking the sexual history. This depends on the patient's complaint, because it always preferable to take the history beginning with the cues the patient offers (e.g., the patient who comes to the emergency room after a fight with her boyfriend can be asked about how long they have been together and what the relationship is like). In situations in which significant history has already been taken and nothing sexual has come up, the clinician may say, “In order to understand you better, it would help to know something about your sexual experiences….” If the patient is not in crisis and the chief complaint does not seem to be sexual in nature, the clinician who has more time may find that the patient speaks more easily if remote (childhood) experiences are discussed first.

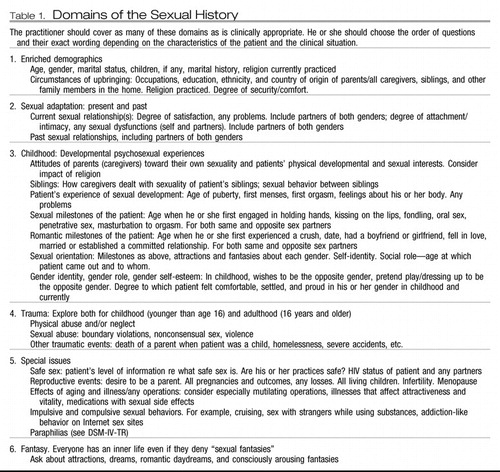

Domains of psychosexual experience that can be useful to explore with patients may be found in Table 1.

|

Table 1.

CONCLUSION

Sexuality is an important part of nearly everyone's life. Even people who have excluded conscious feelings of sexual interest and excitement from their lives usually have family members or partners who are dissatisfied with them because of it. Individuals sworn to celibacy often have vivid sexual fantasy lives and sometimes remarkably active interpersonal sexual lives as well.

The sexual history—because it encompasses development and intersects at so many points with the patient's psychiatric symptoms and illnesses—provides a time line that the clinician and patient can refer to again and again. In our view, learning to take a sexual history is like learning how to do a complete mental status examination or a physical examination and produces vital knowledge that all psychiatrists need to have in their repertoire.

1 Kobak R, Madsen SD: Disruption, in Attachment Bonds: Implications for Theory, Research and Clinical Intervention, 2nd ed. Edited by Cassidy J, Shaver PR, Guilford, NY, 2008, pp 23– 48Google Scholar

2 Diamond M: Clinical implications of the organizational and activational effects of hormones. Horm Behav 2009; 55: 621– 632Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Friedman RC, Downey JI: Psychobiology of late childhood, in Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Columbia University Press, 2008, pp 118– 136Google Scholar

4 Friedman RC, Downey JI: Sexual differentiation of behavior: the foundation of a developmental model of psychosexuality. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2008; 56: 147– 177Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Friedman, RC, Downey, JI: Female homosexuality, in Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Columbia University Press, 2008, pp 136– 160Google Scholar

6 Brownlie EB, Vida R, Beitchman JH, Adlaf EM, Atkinson L, Escobar M, Johnson CJ, Jiang H, Koyama E, Bender D: Emerging adult outcomes of adolescent psychiatric and substance use disorders. Addict Behav 2009; 34: 800– 805Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Cunningham J, Yonkers KA, O'Brien S, Ericksson E: Update on research and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2009; 17: 120– 137Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Rao LI, Chen, LA: Characteristics, correlates and outcomes of childhood and adolescent depressive disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009; 11: 45– 62Google Scholar

9 Kercher AJ, Rapee RM, Schniering CA: Neuroticism, life events and negative thoughts in the development of depression in adolescent girls. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2009; 37: 903– 915Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Pereda N, Guilera G, Froms M, Gomez-Benito J: The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29: 328– 383Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Avis NE, Brockwell W, Randof JF Jr, Shen S, Cain VS, Ory M, Greendale GA: Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause 2009; 16: 442– 452Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Wallace MA: Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nurs 2008; 108: 52– 60Crossref, Google Scholar