Neurocognition as a Treatment Target in Schizophrenia

Abstract

Recent attention has focused on the limitations of current antipsychotic medications for improving community functioning in schizophrenia. The strong relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome has led to a focus on developing pharmacological agents that improve cognition. The potential of this target led to a National Institute of Mental Health initiative known as Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS). Through a series of consensus meetings that included representatives from academia, the pharmaceutical industry, and government, this initiative has developed a consensus battery of neuropsychological tests that can be used as an outcome measure in clinical trials, a pathway to drug approval that has been endorsed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, a priority list of molecular targets for new drug development, and a consensus regarding the design of clinical trials.

There is a serious concern that the current system for drug development is failing in psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia. The case can be made that the current antipsychotic medications—including both first- and second-generation agents—all work through the same mechanism and that the newer agents are merely minor improvements with similar efficacy and improved tolerability. In other words, we have been working with the same basic tools for the past 50 years. The pharmaceutical companies have invested substantial resources in developing drugs for schizophrenia, but the only method for drug development has been to focus on better drugs for decreasing dopamine activity in critical brain areas. These drugs are reasonably effective for attenuating psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia and other illnesses, but they clearly do not have robust effects on other core deficits in schizophrenia such as negative symptoms and impaired cognition (1).

In other areas of medicine—including cardiovascular and infectious diseases—new drugs working through novel mechanisms have transformed these fields. In some cases, drug development has progressed through a better understanding of the pathophysiology of the illnesses themselves. In psychiatry, drugs have usually been developed using animal models that were developed 30–40 years ago.

These concerns about drug development have also come at a time when there is increasing concern about the current medications for schizophrenia. For example, two large trials—the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (2) and the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS) trial from the United Kingdom (3)—have emphasized the fact that the newer drugs were not substantially more effective than older agents. The CATIE study showed that there was widespread dissatisfaction with all antipsychotic drugs, with the majority of patients asking to have their medications changed because of limited efficacy or adverse effects. In addition, advocates for patients and others have suggested that treatment in schizophrenia should focus more on improving functioning and quality of life and less on merely controlling psychotic symptoms. Fifty years of experience with drugs that work through D2 mechanisms suggest that new clinical and biological targets should guide drug development.

TARGETING NEUROCOGNITION

These concerns led Steven Hyman and the late Wayne Fenton from NIMH to consider strategies for advancing drug development by focusing on new targets (4). They proposed dissecting psychiatric disorders into component dimensions of psychopathology that may be more closely related to pathophysiological processes. These components rather than the illnesses themselves may be more amenable to novel pharmacological approaches to therapeutics. This strategy encourages the development of new therapeutic agents for schizophrenia that move beyond positive symptoms as clinical targets to focus on dimensions of the illness most associated with functional disability. Two dimensions stand out as being closely tied to functional disability: negative symptoms and cognitive impairments. If drugs that targeted these dimensions were developed, they would have the potential for improving the functional outcome of schizophrenia.

NIMH chose neurocognition as the target for a number of reasons. The evidence supporting a link between the severity of cognitive impairments and the functional impairments in schizophrenia was particularly convincing. The evidence supporting this relationship was reviewed in an important article by Michael Green (5), and his conclusions have since been reported by others. In addition, basic science research on the neurobiology of cognition has made extensive progress during the past decades. This area of research suggests a number of important paths for improving cognition. This research has been used to assist drug development in other illnesses that affect cognition such as Alzheimer's disease. It is logical that this research may also contribute to research in schizophrenia.

FACILITATING DRUG DISCOVERY: THE MATRICS INITIATIVE

An NIMH approach to facilitating drug development for cognition in schizophrenia was the support of the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) initiative (6). The goal of MATRICS was to address the critical barriers that stood in the way of drug development for this new indication. These barriers included the reluctance of companies to develop a drug development program when it is unclear whether the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would approve a new indication, a lack of a consensus in the field regarding the best means for measuring change in cognition in a clinical trial, a lack of consensus regarding the design of clinical trials for this indication, and a lack of consensus regarding the best molecular targets. MATRICS addressed each of these issues through a transparent consensus building process that involved individuals from industry, government, academia, and consumer groups. More than 300 individuals from these different groups actually participated in MATRICS committees or live meetings.

The issue regarding FDA acceptance of cognition in schizophrenia as an indication was resolved at the first live meeting. A representative from the FDA accepted the fact that there was a pattern of impaired cognition in schizophrenia and that a pharmacological agent addressing these impairments could be approved (7). This could be a comedication that would be added to an antipsychotic or a broad-spectrum drug that was an antipsychotic and improved cognition. For the broad-spectrum agent it would be important that the drug's effects on cognition were not secondary to its antipsychotic effects. This action could be demonstrated in a trial in which the experimental agent was compared with an antipsychotic that did not impair cognition. If both drugs demonstrated a similar antipsychotic effect and the experimental agent had a greater effect on cognition, this would be evidence supporting a claim for improving cognition.

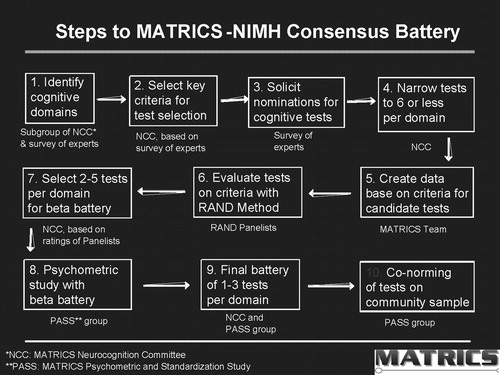

Developing a consensus regarding a battery for measuring cognition in clinical trials required a process that included a large number of individuals over a period of more than 2 years. We adapted a process developed by the RAND Corporation for developing consensus about the appropriateness of different treatments in medicine. This process assured that there was a clear and well-defined path toward consensus. As noted in Figure 1, it began with interviews of experts regarding the criteria that should be used for selecting tests and the domains of neurocognition that should be evaluated in schizophrenia. After the survey, there was an open meeting that included survey participants as well as individuals from government, industry, and consumer groups. During this meeting the results of the survey as well as the results of factor analyses were presented, and a consensus was reached on the domains of cognition. (The results of the meeting can be found at http://www.matrics.ucla.edu). At the live meeting, there was a consensus that social cognition should be included as a domain despite the lack of available data from large trials. Social cognition is usually measured by asking individuals to interpret what is occurring in social situations. These abilities can include interpreting the emotions individuals are expressing in their faces or voices or being able to understand the behaviors and intentions of others. Because these abilities appear to be an important determinant of social skills and functional outcome, they were included in the battery (8, 9).

Figure 1. Steps to MATRICS-NIMH Consensus Battery

After the meeting, candidate tests for each domain were nominated, and data were collected regarding how each met the selection criteria. A panel of experts including neuropsychologists with expertise in schizophrenia, experts in cognition, clinical trialists, psychopharmacologists, and others used these data to rate instruments against the selection criteria. The ratings were then used by a MATRICS Neuropsychology Committee to select the instruments in each domain that best met the criteria. For each domain, two or three tests were selected to “compete” in a psychometric study. This study—the MATRICS Psychometric and Standardization Study (PASS)—was carried out at five sites in the United States and included 167 patients with schizophrenia who were tested on two occasions 1 month apart and 300 community adults for conorming (10). The results of the PASS study led to the final selection of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB). The MCCB has been assembled as a package and can be purchased through a number of test publishers.

The FDA has accepted the MCCB as the gold standard for studies of cognition in schizophrenia. However, at the first MATRICS meeting a representative reported that improvement on neuropsychological tests was not sufficient to support a claim. The expectation was that there would also be improvement in the individual's experience of their cognition or that there would be improvement in a measure that had greater face validity then the test. The FDA did not require evidence that there was improvement in actual community functioning because this was not likely to occur during the time frame of a clinical trial, and factors other than cognition were also related to a patient's obtaining a job or developing social relationships. There was agreement at the meeting that an intermediate measure that documented whether a patient was able to carry out a task would be sufficient even if that person did not actual perform the task in everyday life. This agreement led MATRICS to appoint a group to select instruments that could measure both functional capacity and interview-based measures of cognition. These were included in the PASS study (11). In addition, a second process, MATRICS-CT, is currently underway to evaluate a range of functional capacity measures.

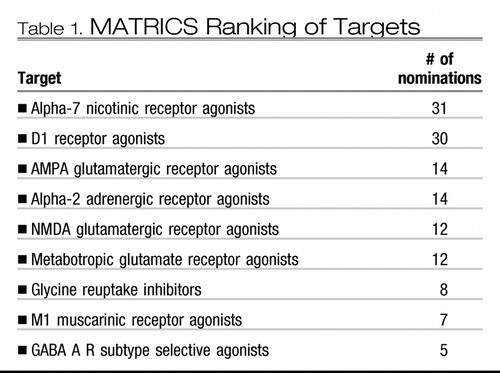

MATRICS also addressed the lack of a consensus about the best molecular targets for drugs to improve cognition in schizophrenia (12). Once again, a group of experts were interviewed to determine the criteria for selecting targets and to propose promising targets. This step was followed by a meeting on the National Institutes of Health campus in Bethesda, MD. where experts presented the data supporting each target. The group was surveyed before and after the meeting. The results are presented in Table 1. α7-Nicotinic and D1 dopamine agonists were viewed as the most promising agents. A number of other targets that would promote glutamate neurotransmission were selected as well as agents affecting GABAA, α-adrenergic, and M1 muscarinic receptors. It is important to note that drugs affecting all of these potential sites are in various stages of development. This indicates that one of the important MATRICS goals has been met.

|

Table 1.

MATRICS also organized an NIMH-FDA workshop to focus on the design of clinical trials that could support a claim for a cognition-enhancing drug (7). The consensus publication recommended that studies be carried out on patients whose conditions were stable with use of an antipsychotic medication. For comedications that would be added to an antipsychotic drug, the experimental medication would be compared with a placebo. As mentioned earlier, an antipsychotic that was being studied for cognitive enhancement would be compared to an antipsychotic that was no worse than cognitively neutral. The primary outcome would be improvement on the composite score from the MCCB and either a functional capacity measure or an interview-based measure of cognition.

THE TURNS NETWORK

NIMH also supported a network of clinical trial sites, Treatment Units for Research on Neurocognition in Schizophrenia (TURNS). This network of seven academic sites used a consensus-based method for selecting compounds that could be studied in a clinical trials network. TURNS trials on a GABAA agonist and a neuroprotective peptide are ongoing, and other studies are in the planning stages.

OTHER ACTIVITIES RELATED TO MATRICS AND TURNS

The MATRICS initiative highlighted an interest among basic neuroscientists, the pharmaceutical industry, government (including NIMH and FDA), neuropsychologists, and clinical psychopharmacologists in collaborating to facilitate drug development. This interest has spawned a number of related efforts that include a collaboration to improve the measurement of negative symptoms in clinical trials (13), an industry-supported consortium to translate the MCCB into languages currently used in large multicenter trials and to evaluate measures of functioning for clinical trials, a collaboration to align preclinical rodent and nonhuman primate models to the MATRICS domains, and a new NIMH program to improve the measurement of real-world outcomes in schizophrenia. Another large NIMH initiative led by Deanna Barch and Cameron Carter addresses one of the limitations of the MCCB. That is, more specific brain-based measures of neurocognition are currently in development. These measures have much greater specificity compared with the traditional neuropsychological tests included in the MCCB. However, these newer measures have not undergone the careful psychometric testing that was necessary to be included in the MCCB. This NIMH initiative, Cognitive Neuroscience Treatment to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (CNTRICS) (14), is developing a plan for evaluating these measures to improve their applicability for clinical trials. Taken together, these efforts demonstrate a model that it is hoped will lead to other attempts to translate discoveries in basic neuroscience into better treatments.

1 Marder SR: Initiatives to promote the discovery of drugs to improve cognitive function in severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:e03Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK, Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:1209–1223Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Jones PB, Barnes TR, Davies L, Dunn G, Lloyd H, Hayhurst KP, Murray RM, Markwick A, Lewis SW: Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:1079–1087Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Hyman SE, Fenton WS: Medicine: what are the right targets for psychopharmacology? Science 2003; 299:350–351Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Marder SR, Fenton W: Measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia: NIMH MATRICS initiative to support the development of agents for improving cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2004; 72:5–9Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Buchanan RW, Davis M, Goff D, Green MF, Keefe RS, Leon AC, Neuchterlein KH, Laughren T, Levin R, Stover E, Fenton W, Marder SR: A summary of the FDA-NIMH-MATRICS workshop on clinical trial design for neurocognitive drugs for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31:5–19Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK: Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2004; 72:29–39Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, Barch DM, Cohen J, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese F, Goldberg TE, Heaton RK, Keefe RS, Kern RS, Kraemer H, Stover E, Weinberger DR, Zalcman S, Marder SR: Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol Psychiatry, 2004; 56:301–307Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese FJ III, Gold JM, Goldberg T, Heaton RK, Keefe RSE, Kraemer H, Mesholam-Gately R, Seidman LJ, Stover E, Weinberger DR, Young AS, Zalcman S, Marder SR: The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:203–213Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Kern RS, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, Keefe RSE, Mesholam-Gately R, Seidman LJ, Stover E, Marder SR: Functional co-primary measures for clinical trials in schizophrenia: results from the MATRICS Psychometric and Standardization Study. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:221–228Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Geyer MA, Tamminga CA: Measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia: neuropharmacological aspects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004; 174:1–2Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT Jr, Marder SR: The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32:214–219Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Carter CS, Barch DM: Cognitive neuroscience-based approaches to measuring and improving treatment effects on cognition in schizophrenia: the CNTRICS initiative. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33: 1131–1137Crossref, Google Scholar