Patient Predictors of Response to Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy: Findings in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program

Abstract

Objective: The authors investigated patient characteristics predictive of treatment response in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Method: Two hundred thirty-nine outpatients with major depressive disorder according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria entered a 16-week multicenter clinical trial and were randomly assigned to interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive-behavior therapy, imipramine with clinical management, or placebo with clinical management. Pretreatment sociodemographic features, diagnosis, course of illness, function, personality, and symptoms were studied to identify patient predictors of depression severity (measured with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) and complete response (measured with the Hamilton scale and the Beck Depression Inventory). Results: One hundred sixty-two patients completed the entire 16-week trial. Six patient characteristics, in addition to depression severity previously reported, predicted outcome across all treatments: social dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, expectation of improvement, endogenous depression, double depression, and duration of current episode. Significant patient predictors of differential treatment outcome were identified. 1) Low social dysfunction predicted superior response to interpersonal psychotherapy. 2) Low cognitive dysfunction predicted superior response to cognitive-behavior therapy and to imipramine. 3) High work dysfunction predicted superior response to imipramine. 4) High depression severity and impairment of function predicted superior response to imipramine and to interpersonal psychotherapy. Conclusions: The results demonstrate the relevance of patient characteristics, including social, cognitive, and work function, for prediction of the outcome of major depressive disorder. They provide indirect evidence of treatment specificity by identifying characteristics responsive to different modalities, which may be of value in the selection of patients for alternative treatments.

In the effort to understand the variability of response to treatments for depression, the relevance of patient characteristics has received much attention. Nevertheless, relatively little systematic research has examined the predictive value of these characteristics in studies comparing different forms of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Certain characteristics of the patient and the nature of the depression may be general indicators of prognosis irrespective of treatment, while others may be indicators of response to individual treatments alone or of differential treatment outcome, that is, preferential response to one or more treatments compared to others. The elucidation of predictors of response addresses an important aspect of treatment specificity by characterizing the type of patients for whom a treatment is most or least effective; it could also have direct clinical applicability in the selection of patients for the most appropriate treatment modality. In addition, some predictors of response to treatment may provide indirect evidence about the putative specific mechanism of a particular modality by indicating patient characteristics that are especially responsive to it, such as functional and relational capacities or type of depression. This may be especially important because only limited evidence about differential treatment effects on measures of outcome hypothesized to be specific to each modality has emerged from this study (1, 2). Although we chose to consider patient characteristics initially, since there is some indication from the literature (3, 4) that they have greater influence on outcome, we plan to address therapist, relationship, and process variables in future analyses.

Comprehensive reviews of general predictors of response to psychotherapy (5, 6) and to tricyclic antidepressants (7–9) reveal that the literature is characterized by lack of consensus about or replication of many findings. The general predictors of response to psychotherapy that have emerged have been derived from many studies based on various psychotherapies, often in small and heterogeneous samples of patients with diverse disorders. Other major reasons for the inconsistent findings among studies include lack of specification of the treatment, variability of inclusion and diagnostic criteria, lack of standardization of outcome measures, variability of criteria for improvement, and differences in selection of patient variables and measures investigated.

The purpose of this article is to report the patient characteristics that predicted treatment response in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (10), which was the first multicenter, comparative clinical treatment trial in the field of psychotherapy research initiated by NIMH. This study compared the efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive-behavior therapy, imipramine with clinical management (as a standard reference condition), and placebo with clinical management (as a control condition) for outpatients with nonbipolar, nonpsychotic major depressive disorder.

Several features of the Collaborative Research Program clinical trial design were considered advantageous for the study of the relation of patient predictors to treatment outcome. First, the multisite, common protocol design permitted study of a larger sample than do most single-site studies, but with uniformity of diagnosis and severity of depression across sites. Second, the extraordinary standardization of the therapies—with treatment manuals, therapist training, and monitoring of the quality of performance—would enhance the prediction of response to specific treatments by reducing the variability of the treatments themselves. Third, the use of a control condition, placebo with clinical management, would help differentiate predictors of response to specific treatments from predictors of general response or response to nonspecific treatment. Fourth, the use of standard outcome measures and response criteria would permit better comparison with the results of other studies. We examined predictors in two groups of patients: 1) those who completed the course of treatment, in order to search for predictors of outcome when there was full exposure to the specific ingredients of the therapies, and 2) all of those who entered the treatment trial, including those who withdrew before completion, in order to search for predictors of the full range of outcomes.

In previous single-site comparative treatment studies of interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy whose results would be most comparable to those of the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, some patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and tricyclic antidepressants were reported. Among the six studies that reported patient predictors of response to cognitive-behavior therapy, one (11) found that pretreatment symptom severity was significantly associated with negative outcome at termination, while another (12) reported an association with positive outcome. Inconsistent findings were reported for endogenous depression (13, 14). Learned resourcefulness, assessed by the Self-Control Schedule, was found to be related to positive outcome (11, 15). Cognitive dysfunction, as measured by the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale, predicted poor response at termination for group cognitive-behavior therapy (16) and negative outcome at 1-year follow-up, though not at termination, for individual cognitive-behavior therapy (17).

Among studies of patient predictors of outcome in interpersonal psychotherapy, initial social adjustment on the Social Adjustment Scale and an index of emotional freedom, education, and occupation predicted positive outcome in social adjustment but not depression severity (4). Endogenous depression was associated with poorer outcome for interpersonal psychotherapy than for tricyclic or combination treatment (18). Situational depression was associated with favorable response to either interpersonal psychotherapy or a tricyclic antidepressant (19).

Among these studies, there were several patient characteristics that predicted response to tricyclic antidepressants. Endogenous depression was associated with favorable outcome with an antidepressant alone or in combination with interpersonal psychotherapy (18), as well as good outcome for patients who completed treatment, but poor outcome for those who dropped out (14). Depression severity was related to negative outcome (11), and learned resourcefulness was related to poor response (15).

Method

A common protocol was conducted at three clinical research sites with a prospective, random-assignment, placebo-controlled design, double-blind for pharmacotherapy and with independent, blind clinical evaluation. A detailed description of the background and design of the main treatment study and the pilot training study has been previously published (10).

The subjects were male and female outpatients between the ages of 21 and 60 years who met the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a current, definite episode of major depressive disorder on the basis of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (20) structured interview and who had a score of 14 or more on the 17-item modified version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (21) for at least 2 weeks before initial screening and again at rescreening after a 1- to 2-week wait or drug washout period. Exclusion criteria consisted of other specific psychiatric disorders, medical contraindications for the use of imipramine, concurrent psychiatric treatment, current active suicide potential, and need for immediate treatment. Patients were clinically referred, voluntary research subjects who gave written informed consent to participate.

All 28 therapists were experienced psychiatrists and psychologists who had received further clinical training by independent expert trainers and had met competence criteria in order to participate. Their performance was monitored throughout the study (10, 22–24). Treatments were conducted in accord with detailed manuals that specified the theoretical rationale, strategies, techniques, and boundaries of each modality (25–27). All treatments were planned to be 16 weeks in duration and to consist of 16–20 sessions. The pharmacotherapy dosage schedule was flexible, with a goal of 200 mg and a maximum of 300 mg. The clinical management component for the pharmacotherapy conditions provided not only guidelines for medication monitoring and management but also support, encouragement, and advice as necessary, although specific psychotherapy interventions were proscribed.

The total sample (N=239) comprised all patients who actually entered treatment from among the 250 patients who met inclusion criteria and were randomly assigned. The completer sample comprised only the patients who completed at least 12 sessions and 15 weeks of treatment and had clinical evaluations at termination. Clinical evaluations were available for 155 patients on the Hamilton depression scale for analyses of depression severity and for 156 patients for analyses of complete response (because of the inclusion of an additional patient for whom the Beck inventory score only was available). There were no statistically significant differences between treatments in overall attrition, treatment-related attrition, or symptomatic failure. Seven patients did not have termination evaluations (1). The findings on comparative treatment efficacy with regard to depressive symptoms and general functioning, modality-specific measures of change, and the temporal course of treatment effect have been reported elsewhere (1, 2, and manuscript by J.T. Watkins et al., submitted for publication).

A comprehensive review of the literature was undertaken to identify patient predictors of response to cognitive-behavior therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and psychotherapy in general, as well as to tricyclic antidepressants and imipramine in particular. Among the predictor variables for which there was evidence of stability and replication, a limited set of independent variables for the multivariate analyses was selected on the basis of the distribution, intercorrelation, reliability, and face validity of the relevant measures. Personality disorders were added on the basis of experience in the pilot study. Because of the potential importance of a cognitive function predictor for cognitive-behavior therapy, the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale total score was selected on an exploratory basis. Two subsequent reports suggesting its relationship to outcome (see the beginning of this article) confirmed that decision.

The 26 independent variables were grouped within three domains: 1) sociodemographic variables-age, sex, marital status, social class; 2) diagnostic and course variables-endogenous, recurrent, primary, situational, and double depression, melancholia, family history of affective disorder, age at onset of first episode, duration of current episode, acuteness of onset of current episode, and number of previous episodes; and 3) function, personality, and symptom variables-social dysfunction, work dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, social satisfaction, expectation of improvement, number of personality disorders, dramatic personality disorder, odd personality disorder, anxiety, somatization/hypochondriasis, and interpersonal sensitivity.

The dependent measures of depression outcome at termination were 1) complete response, a stringent categorical measure based on the combination of a 17-item Hamilton depression scale score less than or equal to 6 and a Beck Depression Inventory (28) score less than or equal to 9, and 2) depression severity, a continuous measure based on the 23-item Hamilton depression scale score, which included cognitive and atypical vegetative symptom items. Two dependent variables were selected to examine predictors of complete response or remission and change in the severity of depression, which would reflect partial response as well. One measure was based solely on clinical evaluator ratings, while the other also incorporated patient self-reports. Scores were based on ratings at termination of treatment for completers and on the last rating obtained for patients who were withdrawn or dropped out (generally, at either interim or early termination evaluation, but for 20 early dropouts, at rescreening evaluation). The interrater reliability, as assessed by intraclass correlation coefficients, for the Hamilton 17-item scale score ranged from 0.92 to 0.96 across sites and from 0.90 to 0.98 within sites; for the Hamilton 23-item scale score it ranged from 0.93 to 0.96 across sites and from 0.89 to 0.98 within sites. The Beck inventory total score showed good internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient equal to 0.78. The percentages of patients achieving complete response were 43.6% (N=68) and 31.4% (N=75) in the completer and total samples, respectively. The mean±SD depression severity scores at termination were 9.43±7.33 and 13.92±10.19 in the completer and total samples, respectively.

Data Analysis

To reduce further the number of independent patient variables from the initial set of 26 for the main predictor analyses across treatments, preliminary multiple regression analyses were conducted within each individual treatment condition, and only the most consistent predictors of outcome within individual treatments were selected for the main analyses. In both the total sample and the completer sample, initial analyses were conducted for independent variables in each of the three single domains, and then the “best” subsets of predictor variables within each domain were combined, with the pretreatment Hamilton depression score included, in final analyses conducted for each outcome measure. For these preliminary analyses we used the method of all possible subsets regression (29), which examines all possible models containing the independent variables and selects the “best” subsets on the basis of an algorithm that uses the criterion of minimal Mallow’s Cp (30) to select the regression model which minimizes the total mean squared error and bias. Each variable in the model contributed a minimum of 2% of the variance to the adjusted R2 value and had a regression coefficient significant at p<0.10.

The subsets of predictor variables that emerged from these multiple regression analyses together constitute a model which best predicts outcome and are indicators of the relative likelihood of favorable or unfavorable outcome for each individual treatment. It should be emphasized, however, that the results do not identify the relative importance of any single variable, since the effect of each variable on outcome variance takes into account the partial effects of all of the other variables in the model. We recognize that, given the number of initial patient variables and the size of the groups in the individual treatment conditions, there is an increased risk of chance findings because of the inherent limitations of the regression analytic approach. We therefore consider these analyses exploratory in nature. While certain predictor relationships replicated earlier findings, other predictors will require further attempts to replicate.

The main data analyses examined the evidence for possible predictors of outcome across all treatments and of differential outcome among treatments. Only 13 variables were selected for these analyses, which were the most consistent predictors of outcome in the final regression analyses within individual treatments, having been predictors in at least two of the four analyses and at a level of significance of p<0.05 in at least one. For depression severity as a continuous measure of outcome, analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were performed, with treatment (four levels) and predictors (two or more levels) as factors in the design and with pretreatment depression severity and marital status as covariates. Marital status was included because it was significantly related to outcome and unevenly distributed among treatment conditions. For continuous predictor variables, patients were divided into two groups by using a median split in score. Significant main effects identified patient variables that predicted outcome across treatments. Significant Predictor by Treatment interactions identified differential treatment effects of patient variables on outcome. For complete response as a categorical measure of outcome, log linear analyses (Treatment by Predictor by Response) were performed, and the “best fit” models were examined for predictor main effects as well as Predictor by Treatment interactions. A significance level of p<0.10 was chosen for the overall difference among treatments. The Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used, so for any individual treatment comparison the obtained probability level had to be <0.017 to be considered significant at an adjusted alpha level of <0.10.

Results

Preliminary predictors within individual treatments

Cognitive-behavior therapy.

The most consistent predictor findings indicated that patients were relatively more responsive to cognitive-behavior therapy if there was lower initial cognitive dysfunction, briefer duration of the current episode of depression, absence of a family history of affective disorder, later age at onset, and a history of more previous episodes of depression. Furthermore, among completers, married patients were relatively more responsive to this therapy.

Interpersonal psychotherapy.

Less social dysfunction was associated with complete response in both samples, accounting for 12%–13% of the outcome variance, and was also associated with good outcome on depression severity in the total sample. The most consistent predictor findings demonstrated that patients, particularly males, who had a lower pretreatment level of social dysfunction, who were separated or divorced, and who had higher interpersonal sensitivity and overall higher satisfaction with social relationships were more responsive to interpersonal psychotherapy. In addition, there was some evidence that patients with more acute onset and endogenous depressive episodes but not double depression responded more favorably to this psychotherapy.

Imipramine with clinical management (imipramine-CM).

Higher work dysfunction was the most robust predictor of good outcome with imipramine-CM in the completer sample for both complete response and depression severity. The most consistent predictor findings indicated that, overall, the patients who showed the most work dysfunction responded best to the effects of imipramine-CM, as did those with highest depression severity and endogenous or primary depression, but those with dramatic personality disorder responded poorly. In the total sample, patients who were not married, had a high level of cognitive dysfunction, or had a low expectation of improvement with treatment responded more poorly.

Placebo with clinical management (placebo-CM).

Among the more consistent predictors, patients of younger age and with higher expectation of improvement appeared to respond more favorably to placebo-CM. Patients with higher levels of initial anxiety and depression severity responded less favorably, as did patients with double depression, who had a lower likelihood of complete response. Low cognitive dysfunction and dramatic personality disorder were associated with worse outcome on depression severity in the total sample only, suggesting a possible relation to attrition in this condition.

Main predictors of response across treatments

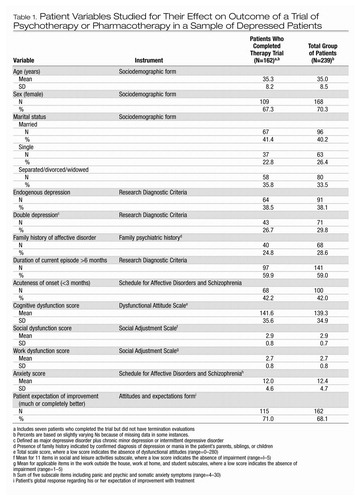

The 13 variables most consistently predictive of outcome within treatments, which were selected for examination of potential prediction of outcome across all treatments or of differential outcome among treatments, were age, sex, marital status, endogenous depression, double depression, family history of affective disorder, duration of current episode, acuteness of onset, cognitive dysfunction, social dysfunction, work dysfunction, anxiety, and patient expectation of improvement. Table 1 shows their distribution in both samples, the instruments with which they were assessed, and notes on their content and scoring.

Overall predictor effects.

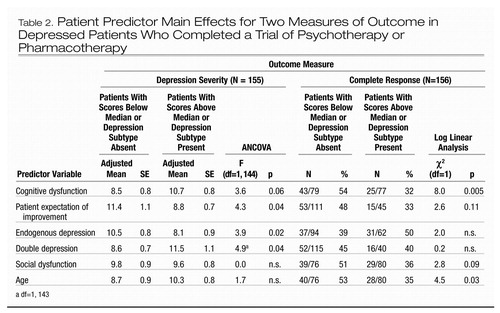

Six patient predictors of outcome of the episode of depression across all treatment conditions were identified from the main effects in the ANCOVAs and log linear analyses in the completer sample (table 2), and another predictor was identified in the total sample only. Lower cognitive dysfunction and higher patient expectation of improvement were significantly associated with both a greater likelihood of complete response and a lower level of depression severity at termination. Significant main effects for expectation of improvement were also present in the total sample for both measures, and a trend effect was present for cognitive dysfunction on complete response. Although not evident in the completer sample, shorter duration of the current episode was significantly associated with both complete response (χ2=2.9, df=1, p=0.09) and lower depression severity (F=5.43, df=1, 228, p=0.02) in the total sample, suggesting that the influence of length of episode on recovery was more notable among patients who discontinued treatment, particularly in the placebo condition.

Endogenous depression was significantly associated with lower depression severity, whereas double depression was associated with higher depression severity, in both the completer and total samples. However, neither variable predicted complete response, suggesting a relation to residual depressive symptoms but not remission per se across all conditions. Lower social dysfunction was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of complete response in both samples but was not related to level of residual depressive symptoms. There was one significant main effect of age on complete response in the completer sample only, with older patients less responsive, particularly in the pharmacotherapy conditions.

Differential predictor effects.

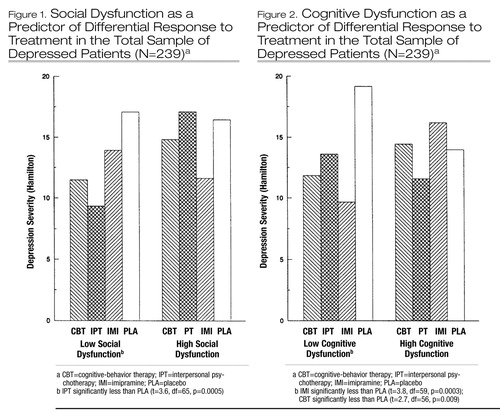

In the ANCOVAs, two of the variables, social dysfunction and cognitive dysfunction, demonstrated significant differential treatment effects on depression severity as outcome in the total sample. Because of considerable heterogeneity of regression with regard to pre-treatment depression Severity, these analyses included only marital status as a covariate. For social dysfunction (figure 1), as measured by the score on the social and leisure activities subscale of the Social Adjustment Scale, there was a significant overall Treatment by Predictor interaction (F=2.84, df=3, 229, p=0.04). When the sample was divided at the median score into high and low social dysfunction, the significant treatment effect appeared only in the group with low social dysfunction (F=4.37, df=3, 116, p=0.006), such that interpersonal psychotherapy patients had the lowest mean depression severity scores at termination, significantly superior to scores in the placebo-CM group. Although there were no significant differences among treatments in the group with high social dysfunction (F=1.44, df=3, 111, n.s.), it should be noted that interpersonal psychotherapy patients had the highest mean severity in that group and the lowest severity in the low social dysfunction group. Thus, level of social functioning most differentiated treatment response among patients who received interpersonal psychotherapy.

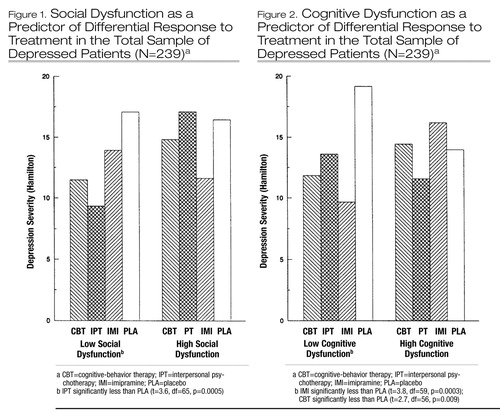

For cognitive dysfunction (figure 2), as measured by the total score on the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale, there was a significant overall Treatment by Predictor interaction (F=4.27, df=3, 229, p=0.006) in the total sample. When separate ANCOVAs were performed for the high and low cognitive dysfunction groups divided at the median, the significant treatment effect appeared only in the low cognitive dysfunction group (F=4.97, df=3, 112, p=0.003), such that patients who received imipramine-CM and patients who received cognitive-behavior therapy had significantly lower depression severity scores at termination than patients who received placebo-CM. Treatment with imipramine-CM yielded the lowest mean depression severity score. Among the high cognitive dysfunction group, there were no significant differences between any of the active treatments and placebo-CM treatment (F=1.56, df=3, 115, n.s.). It is important to note that neither predictor directly distinguished differential response among the three active treatments, but only between the active treatments and the placebo-CM condition. For the patients who completed treatment, there were no significant Treatment by Predictor interactions at the p<0.10 level in the ANCOVAs, although the order of treatment effects was the same.

Log linear analyses also demonstrated significant Treatment by Predictor by Outcome interactions, indicating prediction of differential treatment effects for complete response (Hamilton depression score less than or equal to 6 and Beck inventory score less than or equal to 9) by three predictor variables: social dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and work dysfunction. For social dysfunction there was a significant interaction (χ2=7.0, df=3, p=0.07), and the significant treatment effect was for interpersonal psychotherapy, indicating that patients with low social dysfunction in the total sample treated with interpersonal psychotherapy had a significantly greater chance of complete response than those with high social dysfunction (odds ratio=5.2; χ2=7.4, df=1, p<0.01). For cognitive dysfunction there was also a significant interaction (χ2=6.9, df=3, p=0.08), and the significant treatment effect was for imipramine-CM, demonstrating that patients with low cognitive dysfunction in the total sample had a significantly greater chance of complete response if they were treated with imipramine-CM than did those with high cognitive dysfunction (odds ratio=4.6; χ2=5.8, df=1, p<0.05).

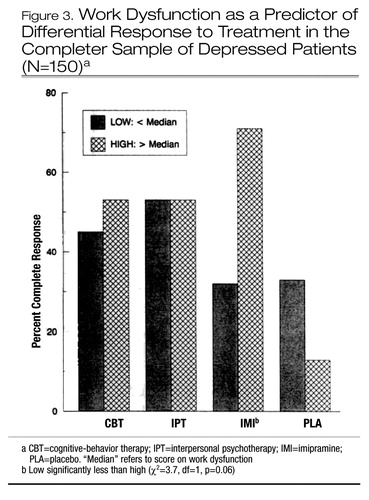

There was a further significant interaction for work dysfunction (χ2=6.7, df=3, p=0.08) (figure 3), and the significant treatment effect was again for imipramine-CM, indicating that patients with high work dysfunction in the completer sample who were treated with imipramine-CM had a significantly greater chance of complete response than those with low work dysfunction (odds ratio=5.0; χ2=3.7, df=1, p=0.06).

Discussion

The results of this collaborative clinical treatment trial comparing the efficacy of two specific forms of psychotherapy with active and placebo pharmacotherapy demonstrate the relevance of patient characteristics for the prediction of outcome from an episode of major depressive disorder. Several characteristics of the depressive episode and patient functioning and cognition were indicators of overall prognosis without regard to the specific treatment received. These six patient predictors of depression severity or complete response were social dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, patient expectation of improvement, endogenous depression, double depression, and duration of current episode.

The results of these analyses also provide evidence for a limited number of characteristics of patient function that significantly predicted differential response to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy with imipramine compared to placebo. There were no significant predictors of differential response among the three active treatments. Among patients with better initial social adjustment (e.g., low social dysfunction), those who received interpersonal psychotherapy became significantly less depressed than those who received placebo-CM and had a higher rate of complete response than those with high social dysfunction. Among patients with less perfectionistic and socially dependent attitudes (e.g., low cognitive dysfunction), those who received treatment with imipramine-CM or cognitive-behavior therapy became significantly less depressed than those who received placebo-CM, and those treated with imipramine-CM also had a higher rate of complete response than those with high cognitive dysfunction. Among patients with more impairment of function at work, school, or home (e.g., high work dysfunction), those who received imipramine-CM had a higher rate of complete response than those with low work dysfunction. The differential predictor effects of social and cognitive dysfunction were observed in the total sample only, which may have been because of 1) the larger size of the total sample, 2) the comparison with all placebo-treated patients rather than placebo completers only, or 3) the inclusion of the full range of outcomes, including attrition, thereby reflecting differential acceptability of the treatments, an important aspect of effectiveness. These differential patient predictors may also provide indirect evidence of the specificity of the treatments by identifying characteristics most responsive to those modalities.

We consider the findings that emerged from both the main analyses across treatments and the preliminary multiple regression analyses within individual treatment conditions exploratory in nature and in need of further replication. The main data analyses (ANCOVAs and log linear analyses) were based on 13 independent variables and 52 analyses (two dependent variables and two samples); with an alpha level of 0.10, approximately one predictor and five analyses would be expected to be significant by chance alone. Although eight variables were identified as significant predictors and there were 16 significant main effects and five interactions among the analyses, some findings (i.e., for age) may have been chance effects and may not be replicable. With the number of initial patient variables and the size of the samples within the preliminary individual treatment analyses, there is a greater risk of chance findings, considering the inherent limitations of the multiple regression analytic approach. Nevertheless, where the interesting patterns of predictors of response within individual treatment conditions are consistent with the results of the main analyses, we include them, with appropriate statistical caution, in the discussion. Given the historical difficulty of replicating predictors across studies, we have emphasized in our interpretation the consistent pattern of findings across samples and measures of outcome. We believe that the main results may be of both theoretical and clinical interest, particularly because of the uncommon effort to compare predictors of differential outcome with a placebo control.

Our finding that social dysfunction was a significant predictor of differential response to interpersonal psychotherapy is consistent with the finding from the individual treatment analyses that greater impairment in social function was associated with poorer response to interpersonal psychotherapy on measures of severity and recovery from depression. One previous study of interpersonal psychotherapy (4) reported that good initial social adjustment predicted good outcome at termination for depressed patients, but only on measures of social function, not depression. Another psychotherapy study (31) also reported that pretreatment social function predicted social function at termination. The finding that favorable response to interpersonal psychotherapy is associated not only with good social adjustment but with previous attainment of a marital relationship, higher satisfaction with social relationships in general, and heightened interpersonal sensitivity seems consistent with reports in the general psychotherapy literature that various indicators of social competence or achievement are associated with good psychotherapy response, whereas social impairment is not. Poor social skills and poor interpersonal relationships have been reported to be related to poor outcome of psychotherapy (32, 33), while perceived social support, social satisfaction, and the ability to develop a good relationship have been associated with favorable response to psychotherapy (31, 34–38). However, this specific relation with pretreatment social adjustment was neither observed nor previously reported for patients treated with cognitive-behavior therapy, the other psychotherapy in our study. Thus, while the study shows that low social dysfunction predicts favorable general prognosis for outcome from depression, it also provides evidence of a specific responsiveness to interpersonal psychotherapy among those patients.

Less impairment in cognitive function as measured by the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale appears to be a general predictor of good prognosis as well as a specific predictor of good response to cognitive-behavior therapy (on depression severity) and imipramine-CM (on both outcome measures). In the two previous studies that examined the relation of dysfunctional attitudes to treatment response, high cognitive dysfunction was also associated with poor outcome at the termination of group cognitive-behavior therapy (16) and poor outcome at 1-year follow-up after individual cognitive-behavior therapy (17). Although in our study cognitive-behavior therapy appeared specifically to improve dysfunctional attitudes concerning the need for social approval (2), there was a less favorable anti-depressant response to cognitive-behavior therapy in patients with greater cognitive dysfunction. This pattern of findings suggests that there may be an important distinction between the empirical effects of cognitive techniques in changing dysfunctional attitudes and a theory that links the presence of dysfunctional attitudes in depression to a preferential response to cognitive therapy.

To our knowledge, the relation of dysfunctional attitudes to outcome with other psychotherapies or pharmacotherapy has not been reported. The finding that in the total sample, low cognitive dysfunction predicted greater likelihood of complete response and greater improvement in depression severity for patients treated with imipramine-CM than for patients treated with placebo-CM was unanticipated. The better outcome of patients who expressed less socially dependent and perfectionistic attitudes may be consistent with the early reports that patients with neurotic (particularly, histrionic and labile) traits and with personality disorders respond poorly to tricyclic antidepressants (7, 39–42). Conversely, the differential predictor and individual treatment results suggest that patients with more socially dependent, dysfunctional attitudes may be more responsive to placebo treatment (3). The possible relation of these attitudes to drug therapy compliance, tolerance of side effects, and acceptance of pharmacotherapy remains to be understood.

Cognitive dysfunction did not predict poor response to interpersonal psychotherapy in this study. Indeed, it appears that the least cognitively impaired patients responded more favorably to cognitive therapy, and the least socially impaired patients responded most favorably to interpersonal psychotherapy. One possible explanation for these results is that each psychotherapy relies on specific and different learning techniques to alleviate depression, and thus each may depend on an adequate capacity in the corresponding sphere of patient function to produce recovery with the use of that approach. Therefore, patients with good social function may be better able to take advantage of interpersonal strategies to recover from depression, while patients without severe dysfunctional attitudes may better utilize cognitive techniques to restore mood and behavior. Patients with more impairment in social or cognitive function might be further overwhelmed and demoralized by a treatment approach that requires reliance on those capacities to achieve improvement. Such patients might respond better to an alternative psychotherapy or combination treatment or require longer-term psychotherapeutic intervention.

Work dysfunction is a major aspect of overall social adjustment in depression, measuring impaired performance, subjective distress, and interpersonal function. Among patients who completed treatment with imipramine-CM, impairment of work function was a significant differential predictor of recovery, and the results on both outcome measures within the individual treatment analyses were consistent. On the contrary, in the few previous studies, social impairment, work disability, and poor employment history have been related to poor outcome with antidepressant medication (39, 43). However, in our study imipramine-CM was previously reported (1) to show consistent, significant superiority over placebo-CM on measures of recovery and symptomatic improvement among the more severely impaired and depressed patients, as defined by the Global Assessment Scale. Furthermore, we observed (manuscript by J.T. Watkins et al., submitted for publication) that imipramine-CM had a significant early advantage for improvement in global social adjustment at 4 weeks and 12 weeks of treatment among the more severely depressed patients. To the extent that impaired work function in depression may result from diminished interest, energy, initiative, and concentration, psychomotor retardation, and social withdrawal, preferential improvement with imipramine would be consistent with the recognized clinical effects of tricyclic antidepressants on these symptoms. This pattern of findings suggests that more severe depression, impairment, and work dysfunction are patient characteristics which are especially responsive to pharmacotherapy with imipramine and which may be of value in the selection of patients for this modality.

In this study endogenous depression was an overall predictor of lower depression severity at termination across all conditions. Previous studies, though, have reported that endogenous depression is a negative indicator of response to psychotherapy, both interpersonal psychotherapy (18) and cognitive-behavior therapy (13). However, Kovacs et al. (14) found endogenous depression to be a positive predictor of outcome for patients who completed treatment with either a tricyclic antidepressant or cognitive-behavior therapy, while Blackburn et al. (44) found no effect of endogenous features on response to either treatment. In our individual treatment analyses for interpersonal psychotherapy, endogenous depression predicted reduction of depression severity. This relationship was not observed for cognitive-behavior therapy. In the individual treatment analyses for imipramine-CM, our finding that endogenous depression was associated with complete response and depression severity corroborates the many previous reports that the endogenous subtype of depression is a major indicator of response to tricyclic antidepressants (7, 14, 18, 19, 45). The lack of differential predictive effect for endogenous depression may be a result of measuring outcome after 4 months, since the differential effect of imipramine-CM on endogenous symptoms was most manifest at 8 and 12 weeks of treatment (manuscript by J.T. Watkins et al., submitted for publication). The reports of situational depression as a predictor of negative outcome for tricyclics and positive outcome for psychotherapy were not replicated, however.

The presence of double depression and the duration of the depressive episode are important aspects of the course of illness that appear to influence response to treatment. In a large naturalistic study uncontrolled for treatment, double depression was associated with favorable outcome from the major depressive episode only, but with poor outcome if outcome was defined as full recovery from the underlying chronic minor depression as well (46–48). In our controlled treatment trial, double depression was predictive of higher depression severity at termination but not of complete response, suggesting a relation to degree of improvement but not remission per se across all treatment conditions. Within the individual treatment analyses, double depression predicted lack of complete response from the episode among patients treated with placebo-CM but not among those who received one of the three active treatments. This may suggest that with active treatment, recovery from the major depressive episode is achieved as readily by patients with double depression as by those without chronic illness, but that more residual depressive symptoms persist among those with double depression. However, patients with double depression treated only by placebo-CM do not recover as readily. Results at follow-up should be most interesting, since previous studies have noted the greatest impact of double depression on subsequent course after recovery from the initial episode (38, 48).

Longer duration of the current episode predicted higher depression severity and a lower rate of complete response in the total sample but not the completer sample, suggesting that the influence of chronicity on recovery was greater among patients who did not complete treatment, most notably in the placebo-CM condition. This finding is consistent with many previous studies that have reported a negative relation between duration of illness and clinical outcome of psychotherapy (49–52), imipramine and other tricyclic antidepressants (34, 39, 53–55), and placebo (34, 56). Previous reports have indicated that acute onset of depression is a positive indicator of response to both tricyclic antidepressant treatment (7, 9, 45) and psychotherapy (33). In our study acute onset was associated with complete response among patients who completed imipramine treatment, and it predicted reduction in depression severity among patients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy, but only in the preliminary analyses within individual treatment conditions. Acute onset did not emerge as a significant predictor of differential treatment outcome in the main analyses. We therefore consider this to be only limited evidence supporting earlier findings.

Last, patients with higher expectation of improvement had a higher likelihood of recovery and lower level of depression severity across treatment conditions in both samples. Within individual treatment analyses, the negative influence of lower expectation of improvement appeared to occur among patients who received only placebo-CM or an incomplete course of imipramine (in the total sample only, not among completers of imipramine treatment). Low expectation of response to pharmacotherapy has been previously reported to predict attrition but not clinical outcome (57). In the psychotherapy literature, the relation of patient expectations to outcome has been generally positive (5, 6), consistent with these results. Other components of patient expectations and attitudes regarding treatment and depression remain to be explored. Since the pattern of findings for several patient predictors suggested a relation to outcome among patients who did not complete treatment, analyses of predictors of attrition are planned. Furthermore, the identification of potential patient predictors of long-term prognosis after initial treatment response will be of considerable clinical interest.

|

Table 1. Patient Variables Studied for Their Effect on Outcome of a Trial of Psychotherapy or Pharmacotherapy in a Sample of Depressed Patients

|

Table 2. Patient Predictor Main Effects for Two Measures of Outcome in Depressed Patients Who Completed a Trial of Psychotherapy or Pharmacotherapy

Figure 1. Social Dysfunction as a Predictor of Differential Response to Treatment in the Total Sample of Depressed Patients (N=239)a

Figure 2. Cognitive Dysfunction as a Predictor of Differential Response to Treatment in the Total Sample of Depressed Patients (N=239)a

Figure 3. Work Dysfunction as a Predictor of Differential Response to Treatment in the Completer Sample of Depressed Patients (N=150)a

1 Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:971–983Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Imber SD, Pilkonis PA, Sotsky SM, et al: Mode-specific effects among three treatments for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990; 58:352–359Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Frank JD: Therapeutic components of psychotherapy: a 25-year progress report of research. J Nerv Ment Dis 1974; 159:325–342Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA: Psychotherapy with depressed outpatients: patient and progress variables as predictors of outcome. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:67–74Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Luborsky L, Auerbach AH, Chandler M, et al: Factors influencing the outcome of psychotherapy: a review of quantitative research. Psychol Bull 1971; 75:145–185Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Garfield SL: Research on client variables in psychotherapy, in Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: An Empirical Analysis, 2nd ed. Edited by Garfield SL, Bergin AE. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1978Google Scholar

7 Bielski RJ, Friedel RO: Depressive subtypes defined by response to pharmacotherapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1979; 2:483–497Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Klein DF, Davis JM: Review of mood-stabilizing drug literature, in Diagnosis and Drug Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. Edited by Klein DF, Davis JM. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1969Google Scholar

9 Joyce PR, Paykel ES: Predictors of drug response in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:89–99Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Elkin I, Parloff MB, Hadley SW, et al: NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: background and research plan. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:305–316Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Simons AD, Lustman PJ, Wetzel RD, et al: Predicting responses to cognitive therapy of depression: the role of learned resourcefulness. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1985; 9:79–89Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Woody GE, McLellan AT, Luborsky L, et al: Severity of psychiatric symptoms as a predictor of benefits from psychotherapy: the Veterans Administration-Penn study. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:1172–1177Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Gallagher DE, Thompson LW: Effectiveness of psychotherapy for both endogenous and nonendogenous depression in older adult outpatients. J Gerontol 1983; 38:707–712Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Kovacs M, Rush AJ, Beck AT, et al: Depressed outpatients treated with cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy: a one-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:33–39Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Murphy GE, Simons AD, Wetzel RD, et al: Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy: singly and together in the treatment of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:33–41Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Keller KE: Dysfunctional attitudes and cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1983; 7:437–444Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Simons AD, Murphy GE, Levine JL, et al: Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: sustained improvement over one year. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:43–48Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Prusoff BA, Weissman MM, Klerman GL, et al: Research Diagnostic Criteria subtypes of depression: their role as predictors of differential response to psychotherapy and drug treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:796–803Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA: RDC endogenous depression as a predictor of response to antidepressant drugs and psychotherapy. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol 1982; 32:165–174Google Scholar

20 Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 38:837–844Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Hamilton MA: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Waskow IE: Specification of the technique variable in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, in Psychotherapy Research: Where Are We and Where Should We Go? Edited by Williams JBW, Spitzer RL. New York, Guilford Press, 1984Google Scholar

23 Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES, Weissman MM: Specification of techniques in interpersonal psychotherapy. IbidGoogle Scholar

24 Shaw BB: Specification of the training and evaluation of cognitive therapists for outcome studies. IbidGoogle Scholar

25 Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, et al (eds): Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

26 Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al (eds): Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, Guilford Press, 1979Google Scholar

27 Fawcett J, Epstein P, Fiester SJ, et al: Clinical management—imipramine/placebo administration manual: NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:309–324Google Scholar

28 Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelsohn M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Frane J: All possible subsets regression, in BMDP Statistical Software. Edited by Dixon WJ. Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1985Google Scholar

30 Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH (eds): Applied Linear Statistical Models, 2nd ed. Homewood, Ill, Irwin, 1985Google Scholar

31 Billings AG, Moos RH: Life stressors and social resources affect posttreatment outcomes among depressed patients. J Abnorm Psychol 1985; 94:140–153Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Luborsky L: The patient’s personality and psychotherapeutic change, in Research in Psychotherapy, vol 2. Edited by Strupp H, Luborsky L. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1962Google Scholar

33 Auerbach AH, Luborsky L, Johnson M: Clinicians’ predictions of outcome of psychotherapy: a trial of a prognostic index. Am J Psychiatry 1972; 128:830–835Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Rosenbaum M, Friedlander J, Kaplan S: Evaluation of results of psychotherapy. Psychosom Med 1956; 8:113–132Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Billings AG, Moos RH: Psychosocial processes of remission in unipolar depression: comparing depressed patients with matched community controls. J Consult Clin Psychol 1985; 53:314–325Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Steinmetz JL, Lewinsohn PM, Antonuccio DO: Prediction of individual outcome in a group intervention for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51:1–7Crossref, Google Scholar

37 McLean PD, Hakstian AR: Clinical depression: comparative efficacy of outpatient treatments. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978; 47:818–836Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Gonzales LR, Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN: Longitudinal follow-up of unipolar depressives: an investigation of predictors of relapse. J Consult Clin Psychol 1985; 53:461–469Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Banki CM: Some clinical and biochemical predictors of outcome in depression. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol 1984; 39: 147–151Google Scholar

40 Klein DF: Diagnosis and pattern of reaction to drug treatment: clinically derived formulations, in The Role and Methodology of Classification in Psychiatry and Psychopathology: Public Health Service Publication 1584. Edited by Katz MM, Cole JO, Barton WE. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1968Google Scholar

41 Nelson JC, Charney DS, Quinlan DM: Characteristics of autonomous depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980; 163:637–643Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Charney DS, Nelson JC, Quinlan DM: Personality traits and disorder in depression. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:1601–1604Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Covi L, Lipman RS, Alarcon RD, et al: Drug and psychotherapy interactions in depression. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:502–508Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Blackburn IM, Bishop S, Glen AIM, et al: The efficacy of cognitive therapy in depression: a treatment trial using cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy, each alone and in combination. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 139:181–189Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Downing RW, Rickels K: Predictors of amitriptyline response in outpatient depressives. J Nerv Ment Dis 1972; 154:248–263Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Keller MB, Shapiro RW: “Double depression”: superimposition of acute depressive episodes on chronic depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:438–442Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Keller MB, Shapiro RW, Lavori PE, et al: Relapse in major depressive disorder: analysis with the life table. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:911–915Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Keller MB, Lavori PW, Endicott J, et al: “Double depression”: two-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:689–694Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Pilkonis P, Imber S, Lewis P, et al: A comparative outcome study of individual, group, and conjoint psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:431–437Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Shapiro AK, Struening E, Shapiro E, et al: Prognostic correlates of psychotherapy in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:802–808Link, Google Scholar

51 Fairweather GW, Simon R, Gebhard ME, et al: Relative Effectiveness of Psychotherapeutic Programs: A Multicriteria Comparison of Four Programs for Three Different Patient Groups. Psychol Monographs 1960; 74(5, Whole Number 492)Google Scholar

52 Fulkerson SC, Barry JR: Methodology and research on the prognostic use of psychological tests. Psychol Bull 1961; 58:177–204Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Raskin A, Boothe H, Reatig N, et al: Initial response to drugs in depressive illness and psychiatric and community adjustment a year later. Psychol Med 1978; 8:71–79Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Kiloh LG, Ball JRB, Garside RD: Prognostic factors in treatment of depressive states with imipramine. Br Med J 1962; 1:1225–1227Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Finnerty RJ, Goldberg HL: Specific response to imipramine and doxepin in psychoneurotic depressed patients with sleep disturbance. J Clin Psychiatry 1981; 42:275–279Google Scholar

56 Raskin A, Boothe H, Schulterbrandt JG, et al: A model for drug use with depressed patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1973; 156:130–142Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Rickels K, Raab E, DeSilvenio R, et al: Drug treatment in depression: antidepressant or tranquilizer? JAMA 1967; 201:675–681Google Scholar