The Role of the Therapeutic Alliance in Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy Outcome: Findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program

Abstract

The relationship between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome was examined for depressed outpatients who received interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive-behavior therapy, imipramine with clinical management, or placebo with clinical management. Clinical raters scored videotapes of early, middle, and late therapy sessions for 225 cases (619 sessions). Outcome was assessed from patients’ and clinical evaluators’ perspectives and from depressive symptomatology. Therapeutic alliance was found to have a significant effect on clinical outcome for both psychotherapies and for active and placebo pharmacotherapy. Ratings of patient contribution to the alliance were significantly related to treatment outcome; ratings of therapist contribution to the alliance and outcome were not significantly linked. These results indicate that the therapeutic alliance is a common factor with significant influence on outcome.

The therapeutic alliance, defined broadly as the collaborative bond between therapist and patient, is widely considered to be an essential ingredient in the effectiveness of psychotherapy. In the ongoing debate about the relative importance of modality-specific techniques versus common factors for therapeutic success in all psychotherapies, the therapeutic alliance has been described as “the most promising of the common elements for future investigation” (Bordin, 1976) and as “the quintessential integrative variable” (Wolfe & Goldfried, 1988) in that it is believed to influence outcome across a range of psychotherapies, despite their therapeutic and technical differences.

In a meta-analysis of therapeutic alliance studies, Horvath and Symonds (1990) concluded that the therapeutic alliance had been significantly associated with outcome not only across a number of investigations but also across different types of psychotherapy. Many of the studies they reviewed, however, included therapists who described their orientations as “eclectic” or who combined treatments with different orientations. Thus, the extent to which the therapeutic alliance affects outcome for carefully defined, specific treatments has remained unclear. A substantial empirical literature attests to the fundamental role played by the alliance in psychodynamic psychotherapy (Luborsky & Auerbach, 1985), but far fewer studies have explored the relationship between alliance and outcome in interpersonal, cognitive, or behavioral treatments. Furthermore, there have been no empirical investigations examining the potential relationship between alliance and outcome in pharmacotherapy.

Recent studies comparing the strength of the alliance in different treatment modalities have produced mixed results. Salvio, Beutler, Wood, and Engle (1992) found no significant differences in alliance levels in a comparison of cognitive versus experiential group therapies for depression, whereas in single “significant” sessions of cognitive behavior and psychodynamic interpersonal therapies, Raue, Castonguay, and Goldfried (1993) found significantly higher total alliance scores for cognitive behavior sessions than for psychodynamic interpersonal sessions. In studies of the relationship between therapeutic alliance and outcome, there is support from some, but not all, studies of cognitive therapy (Castonguay et al., 1993; DeRubeis & Feeley, 1989; Safran & Wallner, 1991). In pharmacotherapy, a positive doctor-patient relationship has been viewed recently as a factor in compliance, but active medication is considered the primary agent of change (Docherty & Feister, 1985). Earlier, however, Downing and Rickels (1978) suggested that factors quite distinct from pharmacological properties, such as the doctor-patient bond, might affect the response to both active medication and placebo.

Only two studies have compared the relationship of alliance to outcome among different standardized treatments. In the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (TDCRP) of interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, and active and placebo pharmacotherapy, Krupnick et al. (1994) conducted a pilot study using a subset of the cases used for the present investigation in an extreme contrast group design. There was a significant relationship between alliance and outcome when ratings were pooled across treatments, but within treatments this relationship was significant only for interpersonal therapy. Mean alliance ratings were significantly higher for psychotherapy than for pharmacotherapy. In a study of cognitive, behavioral, and brief dynamic psychotherapies for elderly depressed patients, Marmar, Gaston, Gallagher, and Thompson (1989) found a significant relationship between alliance and outcome when ratings were pooled across treatments, but within treatments the relationship was significant only in cognitive therapy.

In the current study, we sought to elucidate further the role played by the therapeutic alliance in the outcome of the four treatments in the NIMH TDCRP. We anticipated that findings from this study might differ from our pilot results because of the different study design and much larger sample, that is, all patients who completed at least two sessions. We were interested in learning whether the specific effect of the therapeutic alliance in interpersonal therapy would be sustained and whether the alliance effect might also be demonstrable in cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy with this larger sample, and including the entire range of therapy outcomes.

To our knowledge, this investigation represents the largest study of the therapeutic alliance and outcome ever conducted (N = 225 cases). Furthermore, unlike most alliance studies in the literature, it was carried out within the context of a controlled clinical trial that had the following features: (a) a multisite common protocol design; (b) random assignment to treatment; (c) standardization of the treatments on the basis of manuals (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Fawcett, Epstein, Fiester, Elkin, & Autry, 1987; Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1984); (d) experienced psychiatrist and psychologist therapists who were trained to competency criteria in their respective modalities and monitored for the conduct of the treatment during the study; and (e) the use of a control condition, which allowed the differentiation of treatment-specific from “non-specific” factors.

On the basis of findings from our pilot study as well as other reports in the literature (e.g., Gomes-Schwartz, 1978; Marziali, Marmar, & Krupnick, 1981), we tested the following hypotheses: (a) There would be a significant relationship between the strength of the therapeutic alliance and outcome across treatment conditions; (b) levels of therapeutic alliance would be significantly higher in the psychotherapy groups than in the pharmacotherapy groups; (c) the therapeutic alliance would play a more important role in affecting outcome in psychotherapy than in pharmacotherapy; (d) the association between the strength of the therapeutic alliance and outcome would be significant either in the relationship-focused treatment (interpersonal psychotherapy; IPT) only as in the pilot results, or within all treatments (particularly cognitive behavior therapy [CBT], given the intermediate results for that treatment in the pilot study); (e) early alliance (generally measured in Session 3) would predict outcome in treatments for which alliance and outcome were significantly related; (f) in treatments for which the therapeutic alliance and outcome were significantly related, it would be patient contribution to the alliance that predicted outcome, as has been found in prior investigations of brief dynamic psychotherapy (Marziali et al., 1981).

Method

The research design and methods of the TDCRP have been described in detail elsewhere (Elkin, Parloff, Hadley, & Autry, 1985) and will only be summarized briefly. At each of three research sites, patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatment conditions: interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), imipramine plus clinical management (IMI-CM), or placebo plus clinical management (PLA-CM). The therapies were carried out at George Washington University (Washington, DC), the University of Pittsburgh, and the University of Oklahoma (Oklahoma City).

Patients

Participants in the TDCRP included male and female outpatients between the ages of 21 and 60 who met research diagnostic criteria for a current episode of definite major depressive disorder. The required symptoms had to be present for at least the previous 2 weeks, and patients also had to receive a minimum score of 14 on an amended version of the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD). These criteria had to be present at both the initial screening and the rescreening, which was conducted 1–2 weeks later. Exclusion criteria included specific additional psychiatric disorders and sociopathy (but permitted other concurrent personality disorders), concurrent treatment, specific physical illness or other medical contraindications for the use of imipramine, and imminent suicide potential or need for immediate treatment.

A total of 250 patients met study criteria and were randomly assigned to one of the four treatment modalities; 239 of these patients actually entered treatment. The 225 patients who completed at least two therapy sessions are the subject of this report. Additional description of the sample may be found elsewhere (Elkin et al., 1989).

Therapists

A different group of experienced therapists conducted treatment in each of the conditions, with the exception of the two pharmacotherapy conditions, which were carried out double-blind by the same therapists. Twenty-eight therapists (10 psychologists and 18 psychiatrists) participated in the study, 8 in CBT and 10 each in IPT and pharmacotherapy. Details regarding the selection, training, certification, and characteristics of the therapists are provided elsewhere (Elkin et al., 1985; Rounsaville, Chevron, & Weissman, 1984; Shaw, 1984; Waskow, 1984).

Treatments

All treatments in the TDCRP were carefully defined and standardized with manuals, permitting clarification of relationship versus treatment-specific effects. All treatments, by design, were 16 weeks long, with a range of 16–20 sessions. Psychotherapy sessions were 50 min long; after an initial 45- to 60-min session, all pharmacotherapy sessions were 20–30 min long. Description of the rationale and approach of each treatment may be found elsewhere (Elkin et al., 1989).

Outcome assessment

To assess outcome at termination, we used two widely employed measures of depression severity, the clinical evaluator-rated Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960), modified to include six additional items assessing cognitive symptoms and atypical vegetative function, and the patient self-report Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelsohn, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). Remission was measured by dichotomizing the original 17-item HRSD, with a score of 6 or less indicating remission (see Elkin et al., 1989, for the rationale for this definition).

Process assessment

A modified version of the Vanderbilt Therapeutic Alliance Scale (VTAS) was used to rate the strength of the therapeutic alliance for all of the treatment conditions. In its original form (Hartley & Strupp, 1983), the VTAS is a 44-item measure composed of three subscales, Therapist, Patient, and Therapist-Patient Interaction. This instrument was selected because, on the basis of a review of therapeutic alliance measures conducted for the TDCRP (Hartley, 1985), it was seen as broadly applicable to the treatments under investigation and one of the few measures with available psychometric data on its use by clinical raters. In assessing its feasibility for this study, we judged that the original VTAS was not fully applicable nor its rating manual sufficiently comprehensive to the CBT and pharmacotherapy conditions. Therefore, seven items from the original scale that applied to psychodynamic therapies were deleted, and the rating manual was revised, making the scale and manual more applicable to the different treatments in the TDCRP. Additional “decision rules” were added to the coding manual to help anchor items, providing examples for each of the treatments and aimed at increasing interrater reliability. To further ensure the applicability of the VTAS measure to the CBT and pharmacotherapy approaches, we requested that the TDCRP training investigators for each of the treatments also review the revised measure and coding manual for each of the treatment conditions, and some additional revisions were incorporated.

Procedures

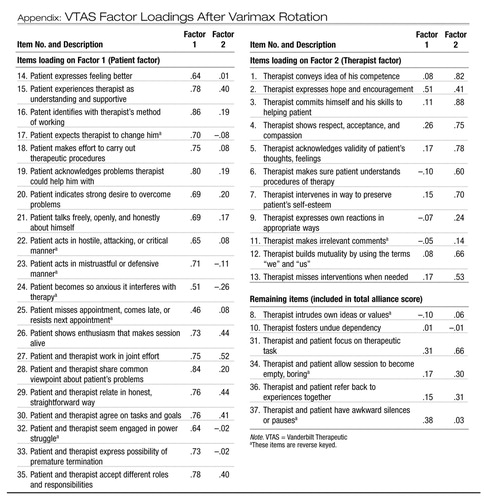

To identify dimensions of the revised VTAS, we factor analyzed the instrument, averaging alliance ratings across sessions for each patient to reduce measurement error. Iterated principal-axis factor analysis was followed by varimax rotation (N = 225 patients). Two factors, Patient factor (20 items) and Therapist factor (11 items), accounted for 50% of the variance and were used for the present analyses along with the total alliance score (see Appendix). It should be noted that the Patient factor included a number of patient and therapist interaction items, which described how the therapy dyad worked in a joint effort.

A total of 619 full-length sessions were rated, with Sessions 3, 9, and 15 rated for each completed case. (For patients who completed only two sessions, Hour 2 was substituted for Session 3.) For dropouts or patients withdrawn from treatment, between one and three tapes were rated, with the last available session substituted for either the middle or late session, depending on the time of dropout or withdrawal. Of the 225 patients, three sessions were rated for 182, two sessions were rated for 30, and one session was rated for 13. The four raters included two masters-level clinical social workers, one doctoral-level clinical social worker, and an advanced clinical psychology doctoral student. Each videotape was viewed and scored by one rater, with 10% coded by two to four raters and a criterion rater (Janice L. Krupnick).

Rater training began with an orientation session in which the theoretical rationale and general approach of each treatment were reviewed. The raters met three times weekly, twice with the trainers (Janice L. Krupnick and Stuart M. Sotsky) and once alone, for 3 months, reviewing videotapes from the training phase of the TDCRP, scoring the VTAS, and comparing and discussing their ratings and decision criteria. Videotapes from the main phase of the TDCRP were scored only after the raters achieved acceptable levels of reliability (.70) on a subset of 16 independently rated training cases. Videotapes were randomly ordered, and raters were kept unaware of session number, type of therapy, and patient outcome. (Once viewing began, it was not difficult to tell what type of treatment was being conducted, but raters were unable to anticipate what type of therapy they would be rating next.) A rater drift procedure (Butler, Rice, & Wagstaff, 1962; Rice, 1965) was used to maintain an acceptable level of interrater agreement throughout the study, with intraclass correlation coefficients assessed every 3 weeks to determine the need for VTAS retraining. Although there were no apparent rater drift problems within the first few months, we instituted bimonthly retraining “booster” sessions because of the lengthy period of time needed to complete the rating task (i.e., over 1 year).

Data analysis

The main data analysis technique was multiple regression for the two continuous-outcome measures (HRSD and BDI) and logistic regression for remission. Each regression equation was calculated in two stages: Stage 1 included the alliance measure, treatment group, and pretreatment symptom severity level (either HRSD or BDI score), whereas Stage 2 added cross-product terms representing the interaction of treatment and alliance. Marital status, which had been used as a covariate in other TDCRP analyses because of its significant relationship to outcome, was examined as a potential covariate, but the inclusion of this variable did not substantially affect the results.

Therapeutic alliance levels were measured in two ways: (a) using early (generally, Session 3) therapeutic alliance scores and (b) using the therapeutic alliance score average for all sessions rated for each patient. Session 3 alone was used because previous studies had examined the influence of initial alliance and because we were interested in learning whether an early measure of relationship could predict therapy outcome. The mean alliance score, averaged over early, middle, and late sessions, was used to improve the stability of the ratings.

Results

Reliability

Interrater reliabilities were estimated by first calculating intraclass correlations for each pair of raters, using the formula for the reliability of a single rating that is based on a random raters design (Fleiss, 1986). The resulting pairwise estimates were then weighted by sample size and averaged. Interrater reliabilities were .66 for the total score: .75 for the Patient factor and .46 for the Therapist factor. On the basis of the early rated session, coefficient alphas were .91 for the total alliance score: .92 for the Patient factor and .82 for the Therapist factor.

Alliance levels within treatment groups

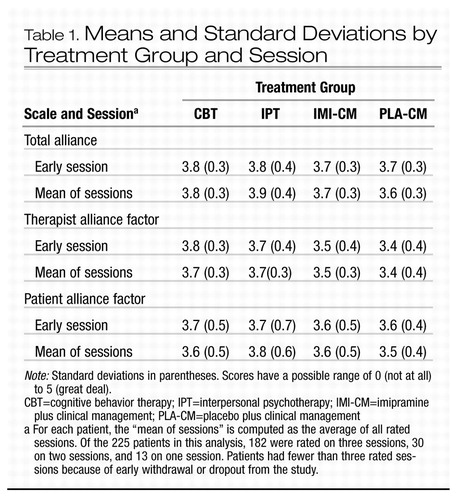

Means and standard deviations for each treatment group are presented in Table 1 for both early session ratings and mean alliance ratings across sessions. The results show that for the total alliance score, as well as for the Patient and Therapist factors, scores were very similar across treatments. There were no significant differences in mean level of the therapeutic alliance observed in interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, or pharmacotherapy with clinical management. Standard deviations were also within a very close range (usually no more than 0.1). The mean scores within and across treatment conditions on all measures of the alliance were in the average-to-good range regardless of treatment condition. Ratings remained quite stable across sessions within all treatment groups.

Alliance and outcome

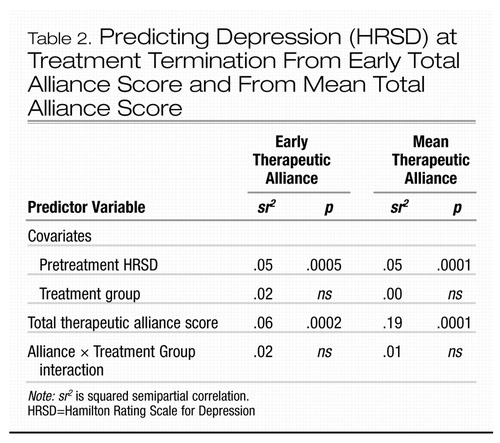

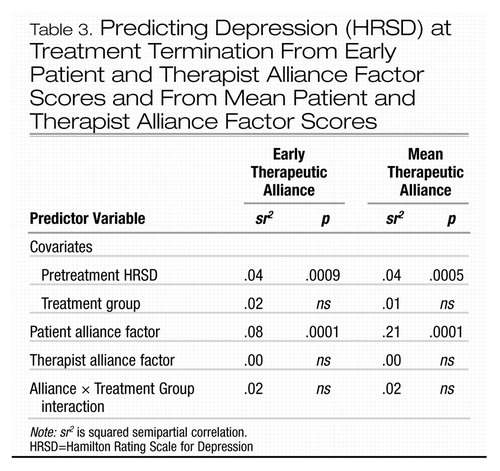

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of the multiple regression analyses associating early and mean total alliance ratings and outcome (Table 2) and early and mean Patient and Therapist Alliance factor scores and outcome (Table 3), which were based on HRSD scores.

Both early and mean therapeutic alliance scores were significantly associated with HRSD-rated outcome, using either total alliance or patient alliance factor scores. Results were very similar when outcome was assessed from the patient perspective on the BDI. Therapist contribution to the therapeutic alliance was not significantly related to outcome for any of the outcome measures, regardless of whether the early or mean therapist alliance factor score was used.

On the basis of early session ratings, patient contribution to the therapeutic alliance accounted for 8% of the variance in treatment outcome (p < .001), using either the HRSD or the BDI. Early total alliance ratings accounted for slightly less of the outcome variance, that is, 6% using the HRSD and 5% using the BDI (p < .001). The logistic regression analyses showed a significant effect of early therapeutic alliance scores on remission for total alliance and Patient factor alliance scores, with an adjusted odds ratio of 3.0 for both (p < .01 for the Patient factor score; p < .05 for total alliance scores). This means that for each unit of increased early total therapeutic alliance or patient contribution to the alliance, the estimated odds of remission increased threefold.

The only Early Alliance × Treatment Method interaction effect was for total alliance on the BDI, where the interaction between strength of the alliance and treatment method accounted for 3% of the variance, F(3, 216) = 2.7, p < .05. Examination of the individual regression coefficients for each of the four treatments indicated that the relationship between total therapeutic alliance score and outcome was relatively strong for IPT, IMI-CM, and PLA-CM, but weak for CBT.

Mean alliance ratings exerted not only a significant but also a very large effect on outcome. On the basis of mean factor scores, the patient contribution to the therapeutic alliance accounted for 21% of the outcome variance on both the HRSD and the BDI (p < .001). Mean total alliance accounted for slightly less of the variance in outcome, that is, 19% on the HRSD and 18% on the BDI (p < .001). The logistic regression analyses showed significant effects of mean Patient factor scores and mean total alliance scores on remission. The adjusted odds ratio was 13.6 for mean Patient factor score (p < .001) and 17.2 for mean total alliance score (p < .001). This indicates that for each unit of increased mean Patient factor alliance, the estimated odds of remission increased more than 13 times; for each unit of increased mean total alliance, the estimated odds of remission increased over 17 times.

There were no significant Mean Alliance × Treatment Method interaction effects in either regression analysis, indicating no evidence that the therapies have different associations between alliance and outcome. Furthermore, there was no evidence of a differential relationship between alliance and outcome for the psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy conditions.

Discussion

This study is the first empirical investigation to compare and contrast levels of therapeutic alliance and their relationship to outcome not only in distinctly different types of psychotherapy but also in pharmacotherapy. The results showed that clinical raters assessed comparable levels of alliance across all of the treatments under investigation. Also worth noting is the high level of mean alliance and small standard deviations in alliance for each therapeutic approach. These uniformly high alliance scores, with means ranging between average and good for all therapies, probably reflect the care with which therapists were selected for the TDCRP and the quality of the training the therapists received. Alliance levels in less carefully monitored studies or in community-based treatments might be lower on average or cover a wider range.

The results also showed a significant relationship between total therapeutic alliance ratings and treatment outcome across modalities, with more of the variance in outcome attributed to alliance than to treatment method. There were virtually no significant treatment group differences in the relationship between therapeutic alliance and outcome in interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, and active and placebo pharmacotherapy with clinical management. The one Early Alliance × Treatment Method interaction effect using the BDI suggested a weaker relationship between early total alliance and clinical outcome for CBT than for the other treatment methods. Because this result was not replicated with the HRSD nor the mean total alliance and outcome, however, it may represent a chance finding.

The association between alliance and outcome was significant whether ratings of alliance were based solely on a single early session or on a mean of alliance across early, middle, and late sessions. This association and the magnitude of outcome variance explained were considerably stronger, however, when mean rather than early alliance alone was used. The inclusion of later sessions, which might reflect clinical response, may partially account for the stronger relationship between mean alliance and outcome. However, Gaston, Marmar, Gallagher, and Thompson (1991) demonstrated that substantial amounts of outcome variance are uniquely accounted for by alliance scores, over and above initial symptomatology and symptomatic change in behavior, cognitive, and brief dynamic psychotherapy. It should be noted that this study, like the TDCRP on which it was based, largely defined outcome in terms of symptom reduction. In contrast, some recent literature has begun to focus on a broader set of outcome domains.

Our findings were consistent with those of Marmar et al. (1989) and Salvio et al. (1992), who reported comparable levels of therapeutic alliance in different types of psychotherapy, including a placebo or minimally supportive condition. These findings support Thurer and Hursch’s (1981) supposition that, even within different approaches, the therapeutic relationship may be established in similar ways. Our findings regarding alliance levels conflict with those of Raue et al. (1993), however, who found significantly different levels of alliance in cognitive behavior and psychodynamic interpersonal sessions; they studied nonstandard therapies in naturalistic settings, unlike our standardized treatments within the context of a research protocol.

Our findings with regard to the relationship of alliance to outcome within different treatment approaches differ not only with those of Marmar et al. (1989), who found a significant relationship only for cognitive therapy, but also with our own pilot study, in which an association was found only for interpersonal therapy. The most likely explanation lies in differences in methodologies. Marmar et al. used patient and therapist ratings to assess the strength of the alliance, whereas we relied on independent observer ratings; observer ratings and patient and therapist reports have shown different relationships of alliance to outcome across a range of studies (e.g., Marziali, 1984). The findings in this article need to be understood in the context of this variability. The TDCRP pilot study (Krupnick et al., 1994) used only a subset of extreme outcome cases, whereas this main study used the full range of participants and outcomes and a much larger number of participants (N = 225), producing a more representative sample; thus, it is a better test of the hypotheses.

An advantage of our methodology over that of earlier alliance studies is that ratings were based on observations of full-session videotapes rather than brief segments of sessions, which has been the typical method. Results are influenced by the data that are available, and full sessions represent a more accurate picture of the alliance than more limited, and hence more arbitrary, sampling. Another distinction of this study was the raters’ training to recognize the features of common relational behaviors across distinctive treatments, despite very different therapist interventions and styles. Because measures that have been developed in the context of dynamic therapy may assess constructs that reflect primarily the specific techniques of that approach rather than generic therapist-patient relational behavior, our revision of the VTAS and its rating manual may have also contributed to a clearer test of the role of the relationship variable in other approaches.

Our findings were consistent with earlier reports (Frieswyk et al., 1986; Horowitz, Marmar, Weiss, DeWitt, & Rosenbaum, 1984; Marmar et al., 1989; Marziali et al., 1981) that found patient contribution to the therapeutic alliance to be a significant predictor of outcome. It is plausible that therapist contribution is also an important factor but the low reliability of the Therapist factor limited our ability to detect a potential association. An examination of variance components (Fleiss, 1986) helps explain the low interrater reliability for the Therapist factor. Similar measurement error rates were found for the Therapist and Patient factors, but there was a more constricted range of alliance ratings for the Therapist factor (true score variance was .09 for the Therapist factor and .26 for the Patient factor). The truncated range of scores, with very few below-average ratings of therapist contribution to the alliance, would make it statistically difficult to detect an effect even if one were present. This was probably because we used only experienced therapists who had extensive training and who met competency criteria and because we monitored their conduct of treatment throughout the study. It is possible that if there had been more variability among the therapists (e.g., inclusion of less skilled or less experienced therapists), an effect on outcome of therapist contribution to the alliance might have been detected. Another possibility is that the therapist contribution to the alliance may be salient only with a particular subset of patients (e.g., those who have the least capacity to form a therapeutic relationship) and that the effect would be diluted by pooling ratings with those of other cases for whom the therapist influence on outcome might be less important.

Perhaps of most interest was the finding of a strong association between alliance and outcome in pharmacotherapy, in both the imipramine and placebo conditions. What this finding suggests is that the therapeutic alliance may strongly influence the placebo response embedded in pharmacotherapy as a nonspecific factor above and beyond the specific pharmacologic action of the drug. The therapeutic alliance may help to create a “holding” environment in which the acceptance of taking a drug may be enhanced and permit concerns to be addressed and worked through within the context of a supportive and collaborative relationship (such as fears of dependence on medication, resistance, and demoralization regarding the delayed or variable effects of medication or placebo and the difficulty tolerating the discomforts of drug side effects). The variability of the doctor-patient relationship may account for the considerable variability in placebo and active drug response rates across studies of tricyclic antidepressants (Morris & Beck, 1974; Sotsky, Barnard, & Docherty, 1983). Thus, the role that the therapeutic alliance plays in affecting outcome extends not only beyond psychodynamic psychotherapy to cognitive behavior therapy, but also beyond psychotherapy itself, with implications for the way in which pharmacotherapy is conceptualized and practiced.

Our findings regarding the relationship between therapeutic alliance and outcome in pharmacotherapy appear particularly salient in light of the recent controversy over the proper settings and providers for the treatment of depression. (Munoz, Hollon, McGrath, Rehm, & VandenBos, 1994). According to the recently published Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) guidelines focused on depression in primary care settings, primary care physicians are encouraged to initiate treatment for their patients with depression in lieu of making a referral to a mental health specialist. As Munoz and his colleagues (1994) pointed out, treatment for depression by primary care physicians is likely to be pharmacological in nature (whether or not that is an appropriate treatment decision). Furthermore, the guidelines suggest that referral to a mental health specialist need not occur until after two unsuccessful antidepressant trials have been carried out by the primary care doctor. This recommendation may be questionable given the results of the present investigation, which provides empirical support for an idea initially asserted by Rickels (1968), that there is more to pharmacotherapy than simply choosing an appropriate medication and dosage level. Munoz et al. (1994) raised doubts as to whether primary care physicians have the requisite training and experience to adequately and effectively work through medication issues with depressed patients. They also note that, given changes that are occurring in the delivery of primary care services (e.g., increased use of large group practices and health maintenance organizations [HMO’s] in which patient information may be provided to an array of personnel), patients and primary care doctors are now less likely to have a close personal relationship than may have been the case in the past. At the very least, it seems that if primary care physicians will indeed be providing a good deal of pharmacological treatment for depression, research into the quality and effect of the therapeutic alliance between patients and physicians in primary care settings is warranted.

In summary, our findings showed that the level, pattern, and effect on clinical outcome of depression of the therapeutic alliance were comparable not only across theoretically and technically different psychotherapies, but also across active and placebo pharmacotherapy conditions. These results are most consistent with the view that the therapeutic alliance is a common relational factor across modalities of treatment for depression that is distinguishable from the specific technical or pharmacological factors within the treatments.

|

Appendix: VTAS Factor Loadings After Varimax Rotation

|

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations by Treatment Group and Session

|

Table 2. Predicting Depression (HRSD) at Treatment Termination From Early Total Alliance Score and From Mean Total Alliance Score

|

Table 3. Predicting Depression (HRSD) at Treatment Termination From Early Patient and Therapist Alliance Factor Scores and From Mean Patient and Therapist Alliance Factor Scores

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. E, & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelsohn, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571.Crossref, Google Scholar

Bordin, E. (1976, September). The working alliance: Basis for a general theory of psychotherapy. Paper presented at the 84th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.Google Scholar

Butler, J. M., Rice, L. N., & Wagstaff, A. K. (1962). On the naturalistic definition of variables: An analogue of clinical analysis. In H. H. Strupp & L. Luborsky (Eds.), Research in psychotherapy (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.Google Scholar

Castonguay, L. G., Wiser, S., Raue, P., Hayes, A. M., &Goldfried, M. R. (1993, June). Predicting change in cognitive therapy for depression: The role of the client’s experiencing the therapist’s focus of intervention, and the working alliance. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Pittsburgh, PA.Google Scholar

DeRubeis, R. J., & Feeley, M. (1989, June). Determinants of change in cognitive therapy for depression. Paper presented at the First World Congress of Cognitive Therapy, Oxford, England.Google Scholar

Docherty, J. P., & Feister, S. J. (1985). The therapeutic alliance and compliance with psychopharmacology. In American Psychiatric Association (Ed.), Psychiatry update (Vol. 4, pp. 607–632). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.Google Scholar

Downing, R., & Rickets, K. (1978). Nonspecific factors and their interaction with psychological treatment in pharmacotherapy. In M. Lipton, A. Dimascio, & K. Killam (Eds.), Psychopharmacology: A generation of progress. New York: Raven Press.Google Scholar

Elkin, I., Parloff, M., Hadley, S., & Autry, J. (1985). NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: Background and research plan. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 305–316.Crossref, Google Scholar

Elkin, I., Shea, T, Watkins, J. T, Imber S. D., Sotsky, S. M., Collins, J. F, Glass, D. R., Pilkonis, P. A., Leber, W. R., Docherty, J. P., Fiester, S. J., & Parloff, M. B. (1989). National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: General effectiveness of treatments. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 971–982.Crossref, Google Scholar

Fawcett, J., Epstein, P., Fiester, S. J., Elkin, I., & Autry, J. H. (1987). Clinical management—imipramine/placebo administration manual: NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 23, 309–324.Google Scholar

Fleiss, J. L. (1986). The design and analysis of clinical experiments (pp. 26–28). New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

Frieswyk, S. H., Allen, J. G., Colson, D. B., Coyne, L., Gabbard, G. O., Horwitz, L., & Newsom, G. (1986). Therapeutic alliance: Its place as process and outcome variable in dynamic psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1, 32–39.Crossref, Google Scholar

Gaston, L., Marmar, C. R., Gallagher, D., & Thompson, L. W. (1991). Alliance prediction of outcome beyond in-treatment symptomatic change as psychotherapy processes. Psychotherapy Research, 1, 104–112.Crossref, Google Scholar

Gomes-Schwartz, B. (1978). Effective ingredients in psychotherapy: Prediction of outcome from process variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 1023–1035.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hamilton, M. A. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology and Neurosurgical Psychiatry, 23, 56–62.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hartley, D. (1985). Measuring the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. Report submitted to the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program, Rockville, MD.Google Scholar

Hartley, D. E., & Strupp, H. H. (1983). The therapeutic alliance: Its relationship to outcome in brief psychotherapy. In J. Masling (Ed.), Empirical studies of psychoanalytical theories. (Vol. 1), Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Google Scholar

Horowitz, M. J., Marmar, C. R., Weiss, D. S., DeWitt, K. N., & Rosenbaum R. (1984). Brief psychotherapy of bereavement reactions: The relationship of process to outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 438–448.Crossref, Google Scholar

Horvath, A. O., & Symonds. B. D. (1990). The relationship between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A synthesis. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Wintergreen, VA.Google Scholar

Klerman, G. L., Weissman, M. M., Rounsaville, B. J., & Chevron, E. S. (1984). Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

Krupnick, J. L., Elkin, I., Collins, J., Simmens, S., Sotsky, S. M., Pilkonis, P. A., & Watkins, J. T. (1994). Therapeutic alliance and clinical outcome in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: Preliminary findings. Psychotherapy, 31, 28–35.Crossref, Google Scholar

Luborsky, L. L., & Auerbach, A. H. (1985). The therapeutic relationship in psychodynamic psychotherapy: The research evidence and its meaning for practice. In R. E. Hales & A. J. Frances (Eds.), Annual review (Vol. 4). Washington. DC: American Psychiatric Press.Google Scholar

Marmar, C. R., Gaston, L., Gallagher. D., & Thompson, L. W. (1989). Therapeutic alliance and outcome in behavioral, cognitive, and brief dynamic psychotherapy in late-life depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177, 464–472.Crossref, Google Scholar

Marziali, E. (1984). Three viewpoints on the therapeutic alliance: Similarities, differences, and associations with psychotherapy outcome. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 172, 417–423.Crossref, Google Scholar

Marziali, E., Marmar, C., & Krupnick, J. (1981). Therapeutic alliance scales: Development and relationship to psychotherapy outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 138, 361–364.Crossref, Google Scholar

Morris, J. B., & Beck, A. T. (1974). The efficacy of anti-depressant drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry, 30, 667–674.Crossref, Google Scholar

Muñoz, R. F, Hollin, S. D., McGrath, J. E., Rehm, L. P., & VandenBos, G. R. (1994). On the AHCPR Depression in Primary Care guidelines: Further considerations for practitioners. American Psychologist, 49, 42–61.Crossref, Google Scholar

Raue, P. J., Castonguay, L. G., & Goldfried, M. R. (1993). The working alliance: A comparison of two therapies. Psychotherapy Research, 3, 197–207.Crossref, Google Scholar

Rice, L. (1965). Therapists’ styles of participation and case outcome. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29, 155–165.Crossref, Google Scholar

Rickels, K. (1968). Non-specific factors in drug therapy. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.Google Scholar

Rounsaville, B. J., Chevron, E. S., & Weissman, M. M. (1984). Specification of techniques in interpersonal psychotherapy. In J. B. W. Williams & R. L. Spitzer (Eds.), Psychotherapy research: Where are we and where should we go? New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

Safran, J. D., & Wallner, L. K. (1991). The relative predictive validity of two therapeutic alliance measures in cognitive therapy. Psychological Assessment, 3(2), 188–195.Crossref, Google Scholar

Salvio, M, Beutler, L. E., Wood, J. M., & Engle, D. (1992). The strength of the therapeutic alliance in three treatments for depression. Psychotherapy Research, 2(1), 31–36.Crossref, Google Scholar

Shaw, B. B. (1984). Specification of the training and evaluation of cognitive therapists for outcome studies. In J. B. W. Williams & R. L. Spitzer (Eds.), Psychotherapy research: Where are we and where should we go? New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

Sotsky, S. M., Barnard, N. D., & Docherty, J. (1983, July). The antidepressant efficacy of imipramine in outpatient studies. Paper presented at the meeting of the World Congress of Psychiatry, Vienna, Austria.Google Scholar

Thurer, S., & Hursch, N. C. (1981). In C. E. Walker (Ed.), Clinical practice of psychology. New York: Pergamon Press.Google Scholar

Waskow, I. E. (1984). Specification of the technique variable in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. In J. B. W. Williams & R. L. Spitzer (Eds.), Psychotherapy research: Where are we and where should we go? New York: Guilford Press.Google Scholar

Wolfe, B. E., & Goldfried, M. R. (1988). Research on psychotherapy integration: Recommendations and conclusions from an NIMH workshop. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 448–451.Crossref, Google Scholar