Personality Disorders

Brief historical review

Personality types and personality disorders

Charting the history of efforts to understand personality types and differences among them would involve exploring centuries of scholarly archives, worldwide, on the varieties of human behavior. It is human behavior, in the end, that serves as the most valid measurable and observable benchmark of personality. In many important ways, we are what we do. The “what” of personality is easier to come by than the “why,” and each of us has a personality style that is unique, almost like a fingerprint. At a school reunion, recognition of classmates not seen for decades derives as much from familiar behavior as from physical appearance.

As to why we behave the way we do, we know now that a fair amount of the reason relates to our “hard wiring.” To varying degrees, heritable temperaments that vary widely from one individual to another determine the amazing range of behavior in the newborn nursery, from cranky to placid. Each individual’s temperament remains a key component of that person’s developing personality, added to by the shaping and molding influences of family, caretakers, and environmental experiences. This process is, we now know, bidirectional, so that the “inborn” behavior of the infant can elicit behavior in parents or caretakers that can in turn reinforce infant behavior: placid, happy babies may elicit warm and nurturing behaviors; irritable babies may elicit impatient and neglectful behaviors.

But even-tempered, easy-to-care-for babies can have bad luck and land in a nonsupportive or even abusive environment, which may set the stage for a personality disorder, and difficult-to-care-for babies can have good luck, protected from future personality pathology by especially talented and attentive caretakers. Once these highly individualized dynamics have had their main effects and an individual has reached late adolescence or young adulthood, his or her personality will usually have been pretty well established. We know that this is not an ironclad rule; there are “late bloomers,” and high-impact life events can derail or reroute any of us. How much we can change if we need to and want to is variable, but change is possible.

Twentieth-century concepts of personality psychopathology

Personality pathology has been recognized in most influential systems of classifying psychopathology. The well-known contributions by European pioneers of descriptive psychiatry such as Kraepelin (1), Bleuler (2), Kretschmer (3), and Schneider (4) had an important impact on early twentieth-century American psychiatry. For the most part, Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Kretschmer described personality types or temperaments, such as asthenic, autistic, schizoid, cyclothymic, or cycloid, which were thought to be precursors or less extreme forms of psychotic conditions such as schizophrenia or manic-depressive illness—systems that can clearly be seen as forerunners of the current axis I/axis II “spectrum” models. Schneider, by contrast, described a set of “psychopathic personalities” that he viewed as separate disorders co-occurring with other psychiatric disorders. Although these classical systems of descriptive psychopathology resonate strongly with the framework eventually adopted by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and published in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), they were widely overshadowed in American psychiatry during the mid-twentieth century by theory-based psychoanalytic concepts stimulated by the work of Sigmund Freud and his followers.

Freud’s emphasis on the presence of a dynamic unconscious—a realm that, by definition, is mostly unavailable to conscious thought but a powerful motivator of human behavior (key ingredients of his topographical model)—was augmented by his well-known tripartite structural theory, a conflict model serving as the bedrock of his psychosexual theory of pathology (5). Freud theorized that certain unconscious sexual wishes or impulses (id) could threaten to emerge into consciousness (ego), colliding wholesale with strict conscience-driven prohibitions (superego), producing “signal” anxiety, precipitating unconscious defense mechanisms and, when these coping strategies proved insufficient, leading to frank symptom formation. For the most part, this system was proposed as explanatory for what were called at the time the “symptom neuroses,” such as hysterical neurosis or obsessive-compulsive neurosis. During the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, these ideas became dominant in American psychiatry, to be followed later by interest in other psychoanalytic principles, such as object relations theory.

Freud’s concentration on the symptom neuroses involved the central notion of anxiety as the engine that led to defense mechanisms and to symptom formation, and as a critical factor motivating patients to work hard in psychoanalysis to face painful realizations and to tolerate stress within the treatment itself (such as that involved in the “transference neurosis”). Less prominently articulated were Freud’s notions of character pathology, but generally, character disorders were seen to represent “preoedipal” pathology. As such, patients with these conditions were judged less likely to be motivated to change. Instead of experiencing anxiety related to the potential gratification of an unacceptable sexual impulse, patients with “fixations” at the oral dependent stage, for example, experienced anxiety when not gratifying the impulse, in this case the need to be fed. Relief of anxiety, then, could be accomplished by some combination of real and symbolic feeding—attention from a parent or parent figure, or even alcohol or drug consumption. Deprivation within the psychoanalytic situation, then, inevitable by its very nature, could lead to the patient’s flight and thus interrupted treatment.

In a way, social attitudes mirrored and extended these beliefs so that although personality pathology was well known, it was often thought to reflect weakness of character or willfully offensive or socially deviant behavior produced by faulty upbringing rather than understood as “legitimate” psychopathology. A good example of this view could be seen in military psychiatry in the mid-1900s, in which discharge from active duty for mental illness with eligibility for disability and medical benefits did not include the “character disorders” (or alcoholism and substance abuse)—these conditions were seen as “bad behavior” and led to administrative, nonmedical separation from the military.

In spite of these common attitudes, clinicians recognized that many patients with significant impairment in social or occupational functioning or with significant emotional distress needed treatment for psychopathology that did not involve frank psychosis or other syndromes characterized by discrete, persistent symptom patterns such as major depressive episodes, persistent anxiety, or dementia. General clinical experience and wisdom guided treatment recommendations for these patients, at least for those who sought treatment. Patients with paranoid, schizoid, or antisocial patterns of thinking and behaving often did not seek treatment. Others, however, often resembled patients with symptom neuroses and did seek help for problems ranging from self-destructive behavior to chronic misery. The most severely and persistently disabled of these patients were often referred for intensive psychoanalytically oriented long-term inpatient treatment (an option much more available at that time than today). Other patients, able to function outside of a hospital setting and often hard to distinguish from patients with neuroses, were referred for outpatient psychoanalysis or intensive psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy. As Gunderson (6) described, the fact that many such patients in psychoanalysis regressed and seemed to get worse rather than showing improvement in treatment was one factor that contributed to the emerging concept of borderline personality disorder, thought initially to be in the border zone between the psychoses and the neuroses. Patients in this general category included some who had previously been labeled as suffering from latent schizophrenia (2), ambulatory schizophrenia (7), pseudoneurotic schizophrenia (8), psychotic character (9), or “as-if” personality (10).

These developments coincided with new approaches emerging within the psychoanalytic framework based on alternative theoretical models, such as the British object relations school. New conceptual frameworks, such as Kernberg’s model of borderline personality organization (11) and Kohut’s concept of the central importance of empathic failure in the histories of narcissistic patients (12), served as the basis for an intensive psychodynamic treatment approach for selected patients with personality disorders.

The DSM system

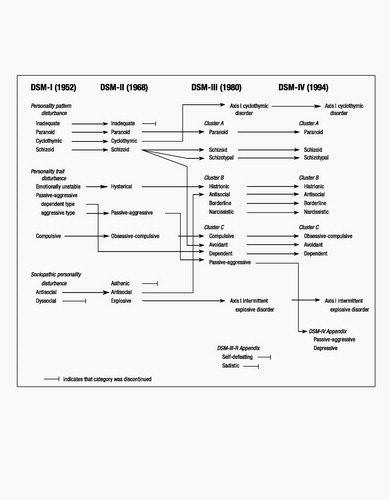

Personality disorders have been included in every edition of the DSM. In 1943, the need for standardized psychiatric diagnosis in the context of World War II drove the U.S. War Department to develop Technical Bulletin 203, describing a psychoanalytically oriented system of terminology for classifying mental illness precipitated by stress (13). APA charged its Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics to solicit expert opinion and to develop a diagnostic manual that would codify and standardize psychiatric diagnoses. This diagnostic system became the framework for the first edition of DSM (1952). DSM-I was widely used and underwent revisions over the years, leading to DSM-II (1968), DSM-III (1980), DSM-III-R (1987), DSM-IV (1994), and DSM-IV-TR (2000). Figure 1 (14) depicts the ontogeny of diagnostic terms relevant to the personality disorders from DSM-I through DSM-IV (DSM-IV-TR involved only text revisions but used the same diagnostic terms as DSM-IV).

Although not explicit in the narrative text, the first edition of DSM reflected the general view of personality disorders at the time, elements of which persist to the present. Generally, personality disorders were viewed as more or less permanent patterns of behavior and human interaction that were established by early adulthood and were unlikely to change throughout the life cycle. Thorny issues such as how to differentiate personality disorders from personality styles or traits, which remain actively debated today, were clearly identified at the time. Personality disorders were contrasted with the symptom neuroses in a number of ways; in particular, the neuroses were characterized by anxiety and distress, whereas the personality disorders were often “egosyntonic,” hence not recognized by those who had them. Even today, we hear descriptions of some personality disorders as “externalizing,” that is, disorders in which the patient disavows any problem but blames all discomfort on the real or perceived unreasonableness of others. Notions of personality psychopathology still resonate with concepts such as those of Reich (15), who described defensive “character armor” as a lifetime protective shield.

In DSM-I, personality disorders were generally viewed as deficit conditions reflecting partial developmental arrests or distortions in development secondary to inadequate or pathological early caretaking. The personality disorders were grouped primarily into “personality pattern disturbances,” “personality trait disturbances,” and “sociopathic personality disturbances.” Personality pattern disturbances were viewed as the most entrenched conditions, likely to be recalcitrant to change, even with treatment. These included inadequate personality, schizoid personality, cyclothymic personality, and paranoid personality. Personality trait disturbances were thought to be less pervasive and disabling, so that in the absence of stress these patients could function relatively well. Under significant stress, however, patients with emotionally unstable, passive-aggressive, or compulsive personalities were thought to show emotional distress and deterioration in functioning, and they were variably motivated for and amenable to treatment. The category of sociopathic personality disturbances reflected what were generally seen as types of social deviance at the time. It included antisocial reaction, dyssocial reaction, sexual deviation, and addiction (subcategorized into alcoholism and drug addiction).

The primary stimulus leading to the development of the second edition of DSM was the publication of the eighth edition of the International Classification of Diseases and the APA’s wish to reconcile its diagnostic terminology with this international system. In the revision process, an effort was made to move away from theory-derived diagnoses and to attempt to reach consensus on the main constellations of personality that were observable, measurable, enduring, and consistent over time. The earlier view that patients with personality disorders did not experience emotional distress was discarded, as were the DSM-I subcategories of personality pattern, personality trait, and sociopathic personality disturbances. One new personality disorder was added, called asthenic personality disorder, only to be deleted in the third edition.

By the mid-1970s, greater emphasis was placed on increasing the reliability of all diagnoses, and, whenever possible, diagnostic criteria that were observable and measurable were developed to define each diagnosis. A multiaxial system was introduced in DSM-III. Disorders classified on axis I included those generally seen as episodic, characterized by exacerbations and remissions, such as psychoses, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Axis II included the personality disorders as well as mental retardation; both groups were seen to comprise early-onset, persistent conditions, but mental retardation was understood to be “biological” in origin, in contrast to the personality disorders, which were generally regarded as “psychological” in origin. The stated reason for placing the personality disorders on axis II was to ensure that “consideration is given to the possible presence of disorders that are frequently overlooked when attention is directed to the usually more florid Axis I disorders” (DSM-III, p. 23). It is generally agreed that the decision to place the personality disorders on axis II has led to greater recognition of the personality disorders and has stimulated extensive research and progress in our understanding of these conditions.

As shown in Figure 1, the DSM-II diagnoses of inadequate personality disorder and asthenic personality disorder were discontinued in DSM-III. The diagnosis of explosive personality disorder was changed to intermittent explosive disorder, and cyclothymic personality disorder was renamed cyclothymic disorder; both of these diagnoses were moved to axis I. Schizoid personality disorder was thought to be too broad a category in DSM-II, and it was unpacked into three personality disorders: schizoid personality disorder, reflecting “loners” who are uninterested in close personal relationships; schizotypal personality disorder, understood to be on the schizophrenia spectrum of disorders and characterized by eccentric beliefs and nontraditional behavior; and avoidant personality disorder, typified by self-imposed interpersonal isolation driven by self-consciousness and anxiety. Two new personality disorder diagnoses were added in DSM-III: borderline personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder. In contrast to the previous notion that patients called “borderline” were on the border between the psychoses and the neuroses, the criteria defining borderline personality disorder in DSM-III emphasized emotional dysregulation, unstable interpersonal relationships, and loss of impulse control more than cognitive distortions and marginal reality testing, which were more characteristic of schizotypal personality disorder. Among the many scholars whose work greatly influenced and shaped our understanding of borderline pathology were Kernberg (11) and Gunderson (6, 16). Although concepts of narcissism had been described by Freud, Reich, and others, the essence of the current views of narcissistic personality disorder emerged from the work of Millon (17), Kohut (12), and Kernberg (11).

DSM-III-R was published in 1987 after an intensive revision process involving widely solicited input from researchers and clinicians. It was based on principles similar to those articulated in DSM-III, such as assuring reliable diagnostic categories that were clinically useful and consistent with research findings and minimizing reliance on theory. Efforts were made for diagnoses to be “descriptive” and to require a minimum of inference, although the introductory text of DSM-III-R acknowledged that for some disorders, “particularly the Personality Disorders, the criteria require much more inference on the part of the observer” (DSM-III-R, p. xxiii). No changes were made in DSM-III-R diagnostic categories of personality disorders, although some adjustments were made in certain criteria sets, for example, making them uniformly polythetic instead of defining some personality disorders with monothetic criteria sets (e.g., dependent personality disorder) and others with polythetic criteria sets (e.g., borderline personality disorder). In addition, two personality disorders were included in Appendix A, “Proposed Diagnostic Categories Needing Further Study”: self-defeating personality disorder and sadistic personality disorder, based on clinical recommendations to the DSM-III-R personality disorder subcommittee. These diagnoses were considered provisional, pending further review and research.

DSM-IV was developed after an extensive process of literature review, data analysis, field trials, and feedback from the profession. Because of the increase in research stimulated by the criteria-based multiaxial system of DSM-III, a substantial body of evidence existed to guide the DSM-IV process. As a result, the threshold for approval of revisions for DSM-IV was higher than those used for DSM-III and DSM-III-R. Diagnostic categories and dimensional organization of the personality disorders into clusters remained the same in DSM-IV as in DSM-III-R, with the exception of the relocation of passive-aggressive personality disorder from the “official” diagnostic list to Appendix B, “Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study.” Passive-aggressive personality disorder, as defined by DSM-III and DSM-III-R, was thought to be too unidimensional and generic; it was tentatively retitled “negativistic personality disorder,” and the criteria were revised. In addition, the two provisional axis II diagnoses in DSM-III-R, self-defeating personality disorder and sadistic personality disorder, were dropped, reflecting insufficient research data and clinical consensus to support their retention. One other personality disorder, depressive personality disorder, was proposed and added to Appendix B. Although substantially controversial, this provisional diagnosis was proposed as a pessimistic cognitive style; its validity and its distinction from passive-aggressive personality disorder on axis II or dysthymic disorder on axis I, however, remain to be established.

DSM-IV-TR, published in 2000, did not change the diagnostic terms or criteria of DSM-IV. The intent of DSM-IV-TR was to revise the descriptive narrative text accompanying each diagnosis, when it seemed indicated, to update the information provided. Only minimal revisions were made in the text material accompanying the personality disorders.

Basic concepts

Definition of a personality disorder

DSM-IV introduced, for the first time, a set of general diagnostic criteria for any personality disorder (Table 1), underscoring qualities such as early onset; the primary, enduring and cross-situational nature of the pathology; and the presence of emotional distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning. Although this effort to specify the generic components of all personality disorders has been helpful, the definition is relatively nonspecific and could apply to many axis I disorders as well, such as dysthymia and even schizophrenia. In fact, DSM-IV-TR states that it “may be particularly difficult (and not particularly useful) to distinguish Personality Disorders from those Axis I disorders (e.g., Dysthymic Disorder) that have an early onset and a chronic, relatively stable course. Some Personality Disorders may have a ‘spectrum’ relationship to particular Axis I conditions (e.g., Schizotypal Personality Disorder with Schizophrenia; Avoidant Personality Disorder with Social Phobia) based on phenomenological or biological similarities or familial aggregation” (p. 688).

Livesley (18) and Livesley and Jang (19) proposed that the two key ingredients of a revised definition for personality disorder might be chronic interpersonal difficulties and problems with a sense of self, notions consistent with Kernberg’s umbrella concept of borderline personality organization (11) that encompasses many of the DSM-IV personality disorder categories and also consistent with earlier concepts of personality pathology (4). Livesley (18) proposed a working definition for personality disorder as a “tripartite failure involving 3 separate but interrelated realms of functioning: self-system, familial or kinship relationships, and societal or group relationships” (p. 141). This proposed revision was suggested as one that could more readily be translated into reliable measures and that derives from an understanding of the “functions of normal personality.” While this definition conceptually links personality pathology with normal personality traits and emphasizes dimensional continuity, how readily measurable a “failure in a self-system” would be seems unclear. More important, this proposed definition could be applied to major axis I conditions such as schizophrenia, unless one added the third criterion for borderline personality organization described by Kernberg (11), namely, maintenance of reality testing.

Whether the current generic personality disorder definition is retained or a new one such as that described above were to be adopted, there would still be a need for specified types of personality disorders, either retaining or modifying the existing categories or replacing them with selected dimensions. In either case, criteria defining the types would be needed.

Dimensional versus categorical

Dimensional structure implies continuity, whereas categorical structure implies discontinuity. For example, being pregnant is a categorical concept (either a woman is pregnant or she is not, even though we speak of how “far along” she is), whereas being tall or short might better be conceptualized dimensionally, since there is no exact definition of either, notions of tallness or shortness may vary among different cultures, and all gradations of height exist along a continuum.

We know, of course, that the DSM system is referred to as categorical and is contrasted to any number of systems referred to as dimensional, such as the interpersonal circumplex (20–22), the three-factor model (23), several four-factor models (24–28), the “Big Five” (29), and the seven-factor model (30). Although the concept of discontinuity is implied by a categorical system, clinicians do not necessarily think in such dichotomous terms. Thresholds defining disease categories, including physical diseases such as hypertension, are in fact somewhat arbitrary, and this is certainly the case with the personality disorders. In addition, the polythetic criteria sets for the DSM-IV-TR personality disorders contain an element of dimensionality; one patient may just meet the threshold and another may meet all criteria, presumably reflecting a more extreme version of the disorder. Widiger (31, 32) and Widiger and Sanderson (33) suggested that this inherent dimensionality in our existing system could be usefully operationalized by stratifying each personality disorder into subcategories of “absent, traits, subthreshold, threshold, moderate, and extreme,” according to the number of criteria met. Certainly if an individual is one criterion short of being diagnosed as having a personality disorder, clinicians do not necessarily assume that there is no element of the disorder present; instead, prudent clinicians would understand that features of the disorder need to be recognized if present and may need attention (34).

Prominent among the issues regarding the use of a categorical system for the personality disorders are that many of the categorical diagnoses are quite heterogeneous, that there is no clear differentiation between normal functioning and pathology, and that there is an extensive amount of overlap of many specific criteria across different diagnoses, so that a careful systematic evaluation for all personality disorders in a given patient quite frequently results in extensive diagnostic co-occurrence on axis II.

Clinical evaluation

Any comprehensive clinical evaluation of a patient should include potential axis II personality disorder pathology. Before a systematic exploration of the possible presence of personality disorder categorical diagnoses is conducted, a general assessment should be made to determine whether the generic elements of a personality disorder are present—pervasiveness across time and circumstances, producing clinically significant impairment in social or occupational functioning, and so on, as indicated in Table 1. Clinicians should have a general familiarity with the DSM-IV-TR personality disorder cluster system, along with prototypical features of each of the personality disorder categories. Generally, clinicians zero in on predominant patterns of personality disturbance, such as cognitive eccentricity, socially isolative behavior, impulsivity, mood dysregulation, or anxiety-driven patterns of behavior. If strong evidence suggests the presence of one of the most disabling personality disorders, such as schizotypal personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, or antisocial personality disorder, it is common for the clinician to explore such possibilities more thoroughly. Often, if persuasive evidence exists for any single personality disorder, that disorder is listed as the axis II diagnosis, and systematic exploration for the presence of other, coexisting personality disorders is not carried out. Studies of clinical practice patterns reveal that clinicians generally assign only one axis II diagnosis (35), whereas systematic studies of clinical populations using semistructured interviews generally reveal multiple axis II diagnoses and significant traits in individuals who have pathology on axis II (36–39). How significantly such a clinical approximation method, which mainly identifies the most prominent “heavy hitter” personality disorder, influences treatment planning is not clear. DSM-IV-TR includes a diagnostic category, personality disorder not otherwise specified, intended to be used when the clinician believes that a patient has a personality disorder that causes significant impairment in functioning, but the patient does not meet the diagnostic threshold for any specific personality disorder. This diagnosis has been reported to be the single most frequently used diagnosis in clinical practice (40), although it is not clear whether it is being used appropriately (41).

Evaluation of axis II pathology is usually carried out by direct questioning of the patient, although, as mentioned above, at least some of these disorders are characterized by their “externalizing” nature, involving defensive denial by the patient of the pathology in question. Semistructured clinical research interviews have dealt with this in various ways, such as asking not only what the patient believes but what others have told the patient or by requiring that another informant who knows the patient well be interviewed as well. When personality pathology is suspected as a major source of the clinical symptomatology, semistructured interviews can be used in clinical work for a more standardized and comprehensive evaluation of axis II. Among the most widely used semistructured interviews are the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (42); the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SIDP-IV) (43); the Personality Disorder Examination (PDE) (44) or its successor, the International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) (45); and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) (46). A number of self-report questionnaires have also been developed, such as the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory–III (MCMI-III) (47), the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory– Personality Disorder Scales (MMPI-PD) (48), and the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4) (49), but these generally have high sensitivity and low specificity and generate significant numbers of false positives; nonetheless, they can be quite useful as initial screening instruments.

Epidemiology

Large-scale epidemiological studies of the DSM-defined personality disorders are limited in number. In earlier broad studies, such as the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (50) and the more recent prevalence study of DSM-III psychiatric disorders in the United States (51), interview methods assessed only antisocial personality disorder among the personality disorders. A large population-based study carried out in Norway by Torgersen et al. (52) using careful methodology revealed an overall prevalence of any DSM-III-R personality disorder of 13.1%, a figure remarkably close to the estimate of 10%–13% previously proposed largely on the basis of clinical populations (53). More recently, Torgersen (54) reviewed the literature and identified eight studies, including that of his own group, that used a reasonable methodology, even though most were smaller studies of subjects not necessarily representative of the general population, such as family members of identified patients. He tabulated these studies for comparison purposes, and the overall personality disorder prevalence, averaged among all eight studies, was 12.3%, with a range of 10% to 14.3%, among the studies with adequate sample sizes. Some interesting differences in prevalences of specific disorders suggest different degrees of genetic loading in different parts of the world. This factor could account, for example, for the high prevalence (5.0%) of avoidant personality disorder in the large Norwegian sample, perhaps reflecting the somewhat isolative and reserved Nordic temperament (55).

In general, in clinical populations, patients with dependent, borderline, obsessive-compulsive, avoidant, and schizotypal personality disorders are overrepresented, and patients with antisocial, schizoid, and paranoid personality disorders are underrepresented (54). Higher prevalences are generally seen in less-educated populations living in congested urban areas. Men more commonly have schizoid, antisocial, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorders, and women more commonly have dependent or histrionic personality disorders. Careful epidemiological studies are clarifying and correcting some misperceptions common in the clinical literature. For example, borderline personality disorder is relatively evenly distributed among men and women, and the personality disorders characterized by introversion or social isolation are more common than generally recognized (54). New data from wave 1 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions indicate that 28.6% of patients with current alcohol use have at least one personality disorder (56), although it is unclear how well the personality disorder assessment method used in this survey correlates with the usual semistructured axis II interviews.

Etiology and neurobiology

One of the truly exciting aspects of psychiatry today is the explosion of knowledge and technology in the neurosciences, making the former “black box” of the brain more and more transparent. Mapping the human genome paved the way for new gene-finding technologies that are being put to work to tackle the complex psychiatric disorders, including the personality disorders. New studies involving animal models are providing important hints about the genetic loci driving certain behavior types, such as attachment and bonding behavior (57). Brain imaging studies are allowing researchers to zero in on malfunctioning areas of the brain in specific personality disorders, and relevant alterations in neurotransmitter levels and functioning are being identified.

Definitive information about specific genetic defects contributing to the personality disorders is still a long way away, as it is for many complex psychiatric disorders, although the central relevance of gene-environment interaction is well accepted for the personality disorders (58). Suggested locations on specific genes that may contribute to temperament dimensions referred to as novelty seeking (59) and reward dependence (60) are being tentatively identified, which may well play a role in selected personality disorders.

Overall, personality types and disorders include many heritable dimensions embedded in complex, mutually influencing genetic and environmental systems. Schizotypal personality disorder has been studied particularly closely, and the evidence is persuasive that it represents partial penetrance of the schizophrenia phenotype (61, 62). Other personality disorders that have been shown to have familial transmission and genetic loading are antisocial personality disorder (63, 64) and borderline personality disorder (55, 65–67).

Studies of the neurobiology of temperament generally focus on dimensions of behavior, such as impulsivity or aggression, rather than on specific personality disorders themselves (68). Such an approach has, for example, clarified the role of serotonin in regulating impulsive aggressive behavior in patients with personality disorders, perhaps especially in males, such as those with borderline personality disorder or antisocial personality disorder (67, 69).

Within the cluster A personality disorders, neurobiological studies have focused largely on patients with schizotypal personality disorder, who show cognitive impairment, structural abnormalities, particularly in the temporal cortex, and subdued dopaminergic activity, clarifying the nature of this personality disorder as a “schizophrenia spectrum disorder” (70, 71).

Studies of cluster B personality disorders have focused primarily on borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. Patients with these disorders demonstrate serotonin dysfunction in connection with impulsive aggression (69). Patients with antisocial personality disorder show decreased prefrontal gray matter volume (72) and increased white matter volume in the corpus callosum (73), perhaps at least partially accounting for deficits in functioning such as affect control and decision making. Brain imaging studies of patients with borderline personality disorder have been inconsistent and difficult to replicate, although most studies suggest reduced volume in limbic structures, particularly the hippocampus and amygdala (74, 75).

Cluster C personality disorders are generally construed to be on the anxiety spectrum and to have neurobiological substrates that in some ways resemble the axis I anxiety disorders. In particular, it is unclear how distinct avoidant personality disorder is from generalized social phobia. Low levels of dopaminergic activity may characterize some cluster C personality disorders as well as axis I anxiety disorders, but more work is needed on the neurobiology of these personality disorders (69).

Treatment

As clinical populations become better defined, new and more rigorous treatment studies are being carried out, with increasingly promising results. No longer are the personality disorders automatically swept into the “hopeless cases” bin. Refining and identifying effective treatment for the personality disorders is particularly important, since they are characterized by significant levels of disability (66, 76), which may be quite persistent (77). Psychiatric treatment of patients with personality disorders involves the following basic principles (78):

| 1. | Since the personality disorders comprise a heterogeneous group of different disorders, no single treatment can be recommended for them all. | ||||

| 2. | Particularly in psychiatrically hospitalized populations, patients frequently have multiple coexisting axis II conditions as well as comorbid axis I and axis II conditions (38, 79); treatment must address all concurrent diagnoses. | ||||

| 3. | Psychotherapy (individual, group, and family) and pharmacotherapy should be considered in treatment planning for the personality disorders. | ||||

| 4. | The personality disorders differ in the degree to which they produce subjective distress as well as in the degree to which they produce significant impairment in social or occupational functioning. As a result, there are great variations in patients’ motivation for treatment. | ||||

| 5. | In general, the cluster A disorders, though they often involve significant impairment in functioning, involve either mistrust or interpersonal aversion, and patients with these disorders do not frequently present for psychiatric treatment. However, they may be persuaded to seek treatment by a concerned friend or family member. | ||||

| 6. | Cluster B disorders are extremely diverse, from highly dysfunctional patients with antisocial personality disorder who rarely seek treatment unless they are seeking relief from legal problems or are forced into treatment by the criminal justice system, to higher-functioning histrionic patients who may experience unhappiness and dissatisfaction but may not feel any need for treatment. Narcissistic patients generally do not recognize or acknowledge their pathology and usually enter treatment only at the insistence of someone else. In this group of disorders, by far the most frequently treated patients are those with borderline personality disorder, since they usually experience great distress and have severe impairment in functioning. | ||||

| 7. | Patients with disorders in cluster C not infrequently seek help. In the case of avoidant personality disorder, this need is often related to persistent social anxiety. Worry about work performance and difficulties in intimate relationships may bring someone with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder to treatment, and concern about being abandoned may motivate an individual with dependent personality disorder to seek help. | ||||

| 8. | In all cases, treatment decisions should be guided primarily by the predominant, presenting problems of the patient. When symptoms such as anxiety, depression, impulsivity, substance abuse, or cognitive and perceptual difficulties predominate, psychopharmacological approaches may be indicated in combination with ongoing psychotherapy. In other cases, where repetitive self-defeating or unfulfilling patterns of behavior are more prominent, targeted forms of time-limited psychotherapy, longer-term psychodynamic psychotherapy, or psychoanalysis may be indicated. | ||||

It has been well established that patients with personality disorders utilize multiple forms of psychosocial and psychopharmacological treatment extensively (80). Too often, the treatment histories of patients with personality disorders suggest erratic “polytherapy,” that is, overloading highly symptomatic patients with multiple treatment efforts without an evidence-based road map. Increasingly, as the personality disorders are better understood, thoughtful treatment strategies are emerging. In particular, an evidence-based practice guideline has been developed for borderline personality disorder (81), which recommends psychotherapy as the primary or core treatment, combined with symptom-targeted adjunctive pharmacotherapy. Randomized controlled trials have shown that a number of different types of psychotherapy are effective for patients with borderline personality disorder, such as dialectical behavior therapy (82) and psychodynamic psychotherapy (83, 84). In addition, new and promising treatments are being studied, such as transference-focused psychotherapy (85) and systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (86). Among other psychotherapies of interest are cognitive behavior therapy (87), interpersonal psychotherapy (88), and schema-based therapy (89). Refinement of the most effective way to combine psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy continues to be quite important (90). It is increasingly clear that careful and systematic application of many types of psychotherapy can be effective (91), and the choice of type of therapy depends on variables such as therapist training and preference, patient preference, patient motivation, and nature of the personality psychopathology in question.

Future directions

There is a general consensus, at least in the United States, that the placement of the personality disorders on axis II has stimulated research and focused clinical and educational attention on these disabling conditions. However, there is growing debate about the continued appropriateness of maintaining the personality disorders on a separate axis in future editions of the DSM and whether a dimensional or a categorical system of classification is preferable. As new knowledge about the personality disorders has rapidly accumulated, these controversies take their places among many ongoing constructive dialogues, such as the relationship of normal personality to personality disorder, the pros and cons of polythetic criteria sets, how to determine the appropriate number of criteria for the threshold required for each diagnosis, which personality disorder categories have construct validity, which dimensions best cover the scope of normal and abnormal personality, and others (92). Emerging data from the Collaborative Personality Disorders Study raise substantive questions about some of our assumptions about the personality disorders, for example, that they are enduring and stable over time and across situations (93, 94). Many of these discussions overlap with and inform each other, and steady progress in our understanding and treatment of these disabling disorders can be anticipated.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 1. Ontogeny of Personality Disorder Classification

Source:Skodol AE: Classification, assessment, and differential diagnosis of personality disorders. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 1997; 3:261–274

1 Kraepelin E: Lectures on Clinical Psychiatry (English edition). New York, Wood Press, 1904Google Scholar

2 Bleuler E: Textbook of Psychiatry. Translated by Brill AA. New York, Macmillan, 1924Google Scholar

3 Kretschmer E: Hysteria (English edition). New York, Nervous and Mental Disease Publishers, 1926Google Scholar

4 Schneider K: Die Psychopathischen Personlichkeiten. Vienna, Deuticke, 1923Google Scholar

5 Freud S: Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety (standard edition). London, Hogarth Press, 1926Google Scholar

6 Gunderson JG: Borderline Personality Disorder: A Clinical Guide. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2001Google Scholar

7 Zillborg G: Ambulatory schizophrenia. Psychiatry 1941; 4:149–155Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Hoch PH, Polatin P: Pseudoneurotic forms of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q 1949; 23:248–276Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Frosch J: The psychotic character: clinical psychiatric considerations. Psychiatr Q 1964; 38:81–96Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Deutsch H: Some forms of emotional disturbance and their relationship to schizophrenia. Psychoanal Q 1942; 11:301–321Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Kernberg O: Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. New York, Jason Aronson, 1975Google Scholar

12 Kohut H: The Analysis of the Self. New York, International Universities Press, 1971Google Scholar

13 Barton WE: The History and Influence of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987Google Scholar

14 Skodol AE: Classification, assessment, and differential diagnosis of personality disorders. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 1997; 3:261–274Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Reich W: Character Analysis. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1945Google Scholar

16 Gunderson JG: Borderline Personality Disorder. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1984Google Scholar

17 Millon T: Modern Psychopathology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1969Google Scholar

18 Livesley WJ: Suggestions for a framework for an empirically based classification of personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1998; 43:137–147Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Livesley WJ, Jang KL: Toward an empirically based classification of personality disorder. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:137–151Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Benjamin LS: Interpersonal Diagnosis and Treatment of Personality Disorders. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

21 Wiggins J: Circumplex models of interpersonal behavior in clinical psychology, in Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology. Edited by Kendall P, Butcher J. New York, Wiley, 1982Google Scholar

22 Kiesler DJ: The 1982 interpersonal circle: a taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychol Review 1983; 90:185–214Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG: Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. San Diego, Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1975Google Scholar

24 Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, Vernon PA: Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1826–1831Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Watson D, Clark LA, Harkness AR: Structures of personality and their relevance to psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:18–31Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Clark LA, Livesley WJ, Schroeder ML, Irish SL: Convergence of two systems for assessing specific traits of personality disorder. Psychol Assess 1996; 8:294–303Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA: Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:941–948Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Widiger TA: Four out of five ain’t bad. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:865–866Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Costa PT, McCrae RR: The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. J Personal Disord 1992; 6:343–359Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR: A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:975–990Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Widiger TA: Definition, diagnosis, and differentiation. J Personal Disord 1991; 5:42–51Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Widiger TA: Issues in the validation of the personality disorders. Prog Exp Pers Psychopathol Res 1993; 16:117–136Google Scholar

33 Widiger TA, Sanderson CJ: Toward a dimensional model of personality disorder, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford Press, 1995Google Scholar

34 Oldham JM, Morris LB: The New Personality Self-Portrait. New York, Bantam, 1995Google Scholar

35 Westen D: Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:895–903Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Skodol AE, Link BG, Shrout PE, Horwath E: The revision of axis V in DSM-III-R: should symptoms have been included? Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:825–829Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Widiger TA, Frances AJ, Harris M, Jacobsberg L, Fyer M, Manning D: Comorbidity among axis II disorders, in Personality Disorders: New Perspectives on Diagnostic Validity. Edited by Oldham JM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1991Google Scholar

38 Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Kellman HD, Hyler SE, Rosnick L, Davies M: Diagnosis of DSM-III-R personality disorders by two structured interviews: patterns of comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:213–220Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Shedler J, Westen D: Refining personality disorder diagnosis: integrating science and practice. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1350–1365Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Verheul R, Widiger TA: A meta-analysis of the prevalence and usage of the personality disorder not otherwise specified (PDNOS) diagnosis. J Personal Disord 2004; 18:309–319Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Skodol AE: Manifestation, clinical diagnosis, and comorbidity, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

42 First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II), User’s Guide. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

43 Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M: Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

44 Loranger AW: Personality Disorder Examination (PDE) Manual. Yonkers, NY, DV Communications, 1988Google Scholar

45 Loranger AW: International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE). Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1999Google Scholar

46 Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Yong L: The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Belmont, MA, McLean Hospital, Laboratory for the Study of Adult Development, 1996Google Scholar

47 Millon T, Millon C, Davis R: Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory–III: Manual for MCMI-III, 2nd ed. Minneapolis, National Computer Systems, 1997Google Scholar

48 Morey LC, Waugh MH, Blashfield RK: MMPI scales for DSM-III personality disorders: their derivation and correlates. J Pers Assess 1985; 49:245–251Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Hyler SE: Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire–4 (PDQ-4). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1994Google Scholar

50 Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 42:381–389Google Scholar

51 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshelman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–14Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V: The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiat 2001; 58:590–596Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Weissman MM: The epidemiology of personality disorders: a 1990 update. J Personal Disord 1993; 7(suppl 1):44–62Google Scholar

54 Torgersen S: Epidemiology, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

55 Torgersen S, Lygren S, Oien PA, Skre I, Onstad S, Edvardsen J, Tambs K, Kringlen E: A twin study of personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2000; 41:416–425Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP: Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:361–368Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Insel TR, Young LJ: The neurobiology of attachment. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001; 2:129–136Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Cloninger CR: Genetics of personality disorders, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

59 Cloninger CR, Adolfsson R, Svrakic NM: Mapping genes for human personality. Nat Genet 1996; 12:3–4Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Mitropoulou V, Trestman RL, New AS, Flory JD, Silverman JM, Siever LJ: Neurobiologic function and temperament in subjects with personality disorders. CNS Spectr 2003; 8:725–730Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Kendler KS, Gruenberg AM, Strauss JS: An independent analysis of the Copenhagen sample of the Danish adoption study of schizophrenia, II: the relationship between schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:982–984Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Siever LJ, Silverman JM, Horvath TB, Klar H, Coccaro E, Keefe RS, Pinkham L, Rinaldi P, Mohs RC, Davis KL: Increased morbid risk for schizophrenia-related disorders in relatives of schizotypal personality disordered patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:634–640Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Cadoret RJ, Troughton E, O’Gorman TW: Genetic and environmental factors in alcohol abuse and antisocial personality. J Stud Alcohol 1987; 48:1–8Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Iacono WG, McGue M, Patrick CJ: Family transmission and heritability of externalizing disorders: a twin-family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:922–928Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Siever LJ, Torgersen S, Gunderson JG, Livesley WJ, Kendler KS: The borderline diagnosis, III: identifying endophenotypes for genetic studies. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:964–968Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, Grilo CM, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Oldham JM: Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:276–283Crossref, Google Scholar

67 New AS, Siever LJ: Neurobiology and genetics of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Annals 2002; 32:329–336Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Siever LJ, Davis KL: A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1647–1658Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Coccaro E, Siever L: The neurobiology of personality disorder, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

70 Downhill JE Jr, Buchsbaum MS, Hazlett EA, Barth S, Lees Roitman S, Nunn M, Lekarev O, Wei T, Shihabuddin L, Mitropoulou V, Silverman J, Siever LJ: Temporal lobe volume determined by magnetic resonance imaging in schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2001; 48:187–199Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Siever LJ, Davis KL: The pathophysiology of schizophrenia disorders: perspectives from the spectrum. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:398–413Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Raine A, Lencz T, Bihrle S, LaCasse L, Colletti P: Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:119–127; discussion, 128–129Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Raine A, Lencz T, Taylor K, Hellige JB, Bihrle S, Lacasse L, Lee M, Ishikawa S, Colletti P: Corpus callosum abnormalities in psychopathic antisocial individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:1134–1142Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Driessen M, Herrmann J, Stahl K, Zwaan M, Meier S, Hill A, Osterheider M, Peterson D: Magnetic resonance imaging volumes of the hippocampus and the amygdala in women with borderline personality disorder and early traumatization. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:1115–1122Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Nahas Z, Molnar C, George MS: Brain imaging, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

76 Skodol AE, Pagano ME, Bender DS, Shea MT, Gunderson JG, Yen S, Stout RL, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH: Stability of functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder over two years. Psychol Med 2005; 35:443–451Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Seivewright, H, Tyrer P, Johnson T: Persistent social dysfunction in anxious and depressed patients with personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 109:104–109Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Oldham JM: Personality disorders: current perspectives. JAMA 1994; 272:1770–1776Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Kellman HD, Hyler SE, Doidge N, Rosnick LM: Comorbidity of axis I/axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:571–578Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, Dyck IR, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Oldham JM: Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:295–302Crossref, Google Scholar

81 American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158(Oct suppl)Google Scholar

82 Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

83 Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1563–1569Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Bateman A, Fonagy P: Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: an 18-month follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:36–42Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Clarkin JF, Foelsch PA, Levy KN, Delaney JC, Kernberg OF: The development of a psychodynamic treatment for borderline personality: a preliminary study of behavioral change. J Personal Disord 2001; 15:487–495Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Blum N, Pfohl B, John DS, Monahan P, Black DW: STEPPS: a cognitive-behavioral systems-based group treatment for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a preliminary report. Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:301–310Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Beck A, Freeman A, Davis D: Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford Press, 2003Google Scholar

88 Markowitz JC: Interpersonal therapy, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

89 Young J, Klosko J: Schema therapy, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

90 Soloff PH: Somatic treatments, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

91 Leichsenring F, Leibing E: The effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1223–1232Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Oldham JM, Skodol AE: Charting the future of axis II. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:17–29Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Grilo CM, McGlashan TH: Course and outcome of personality disorders, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

94 Grilo C, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Stout RL, Pagano ME, Yen S: Two-year stability and change of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72:767–775Crossref, Google Scholar

95 Widiger TA: Personality disorder dimensional models proposed for DSM-IV. J Personal Disord 1991; 5:386–398Crossref, Google Scholar