Hepatitis C and Psychiatry

Abstract

Approximately 4 million Americans are chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Compared with the general U.S. population, patients with HCV have a higher prevalence of psychiatric illness, and patients with severe mental illness have four to nine times the prevalence of HCV. The use of interferon-alpha (IFN) to eradicate HCV has been associated with frequent neuropsychiatric adverse effects (e.g., affective, anxiety, cognitive, and psychotic symptoms) that compromise the management of HCV patients with and without a preexisting history of psychiatric illness. Psychiatric symptoms often result in the interruption, dose reduction, or cessation of IFN therapy, which makes treatment of patients with comorbid HCV and psychiatric illness a challenge. IFN can be safely administered to psychiatric patients with HCV but requires a comprehensive pretreatment assessment, a risk-benefit analysis, and ongoing psychiatric follow-up. This review summarizes the psychiatric implications of HCV infection and strategies for the management of IFN-induced neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection affects 170 million people around the world (1) and 2% of the U.S. population (2, 3). It is the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States; left untreated, the liver disease can progress to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and, rarely, hepatocellular carcinoma (4). In 2005 more U.S. patients will die from HCV-induced liver disease than from HIV/AIDS (5).

HCV is a neuropathic RNA-based virus from the Flaviviridae family (which includes, among others, the West Nile encephalitis virus) (6). HCV has six different genotypes; however, only genotypes 1, 2, and 3 are common in the United States (7). Up to 70% of U.S. HCV patients are infected with genotype 1, with genotypes 2 and 3 together accounting for the remainder (8).

The natural history of HCV infection is highly variable (9). Approximately 85% of persons infected with hepatitis C develop lifelong chronic infection (10). Some 5%–20% of individuals with chronic HCV infection will develop cirrhosis over a span of 10–25 years. Alcohol use may accelerate the process toward cirrhosis (4). Those who develop cirrhosis have an elevated risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (a risk of 1%–4% per year), and up to 20% will develop end-stage liver disease (11).

Well-established HCV risk factors include intravenous (IV) drug use, blood or blood product transfusions prior to 1992, and hemodialysis (5). Targeted screening for HCV infection in patients with one or more of these risk factors has been recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is clearly warranted (12). However, evidence is beginning to emerge that other patient groups may also have an elevated risk of HCV infection (13). These groups include non-IV drug users (14–16), patients with high-risk sexual practices (e.g., men having sex with men), and patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals (17). Two distinct demographic groups that have an elevated prevalence of HCV infection and receive their medical care in specialized settings include patients followed at Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals (18, 19) and incarcerated individuals (20).

Although HCV is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, having multiple sexual partners is a risk factor (5). Interestingly, sexual transmission of HCV is far less efficient than that of HIV (2). The CDC reports that only 1.5% of partners of HCV carriers test positive for the disease, and the estimated risk of vertical transmission (mother to infant) is only 5% (5). The transmission of HCV infection through tattooing and body piercing remains a controversial issue. The CDC’s view is that the data are insufficient to consider persons with tattoos and body piercings to have an elevated risk of HCV infection (5). Table 1 lists the prevalence rates of HCV infection in populations of interest to psychiatrists and the percentage these groups represent in the general U.S. population.

Hepatitis C screening

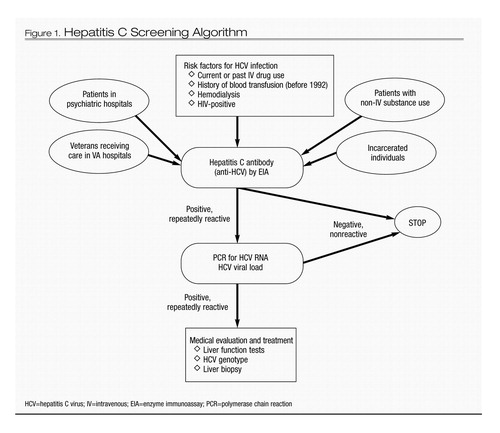

The optimal screening method for HCV infection is HCV antibody (anti-HCV) testing with a third-generation enzyme immunoassay (21). In high-risk populations, anti-HCV has a sensitivity and specificity of 94%–96% (21). Quantitative HCV RNA counts by polymerase chain reaction confirm HCV viremia and help in monitoring treatment response. HCV genotyping is used to guide the duration of treatment with therapies based on interferon-alpha (IFN) and as a prognostic indicator for response to IFN treatment (2).

A negative anti-HCV test usually excludes HCV infection. However, psychiatrists should be aware of two instances in which a patient with a negative anti-HCV test can still have HCV infection (10): immunocompromised individuals (e.g., patients with cancer or HIV/AIDS) and patients with acute HCV infection (i.e., less than 3 months) (22). In both of these circumstances, serial HCV RNA measurements can confirm or exclude viremia (23).

After confirmation of HCV infection, a liver biopsy is an important diagnostic procedure to assess the extent of HCV-induced liver disease (e.g., inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis) and to inform the need for therapy. Another liver biopsy after IFN treatment can be used to ascertain whether any HCV-induced liver disease has resolved (6). Figure 1 presents a simplified screening algorithm for HCV infection.

HCV posttest counseling

Patients who are found to be infected with HCV should be counseled on prevention of the spread of the virus to others (5, 6). Table 2 lists the recommended points to be covered in posttest counseling for HCV. HIV testing should be offered, given that 5%–10% of patients with HCV are coinfected with HIV (24). HCV can be transmitted through common household objects such as toothbrushes, shaving utensils, and other personal items. Although HCV infection has a low rate of sexual transmission (and particularly low rates of transmission among long-term monogamous partners), patients should still be advised to practice safe sex and use barrier protection to further reduce the risk of transmission of HCV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Alcohol use, even in moderation, has been shown to accelerate the progression of HCV-induced liver disease (25). Consequently, HCV patients should be advised to eliminate any alcohol use (26).

Rationale for screening and treatment of chronic HCV infection

Recent advances in the treatment of HCV and the introduction of pegylated interferons (PEG-IFNs) in combination with ribavirin have resulted in an improved sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as complete eradication of HCV with no detectable HCV viral load 6 months after IFN treatment is completed (27). Among patients with HCV genotype 1, SVR rates are 50%–60%, and among patients with HCV genotypes 2 or 3, it is 80%–90% (28). Several factors have been associated with reduced SVR rates: male gender; African American race; increased body mass index; advanced age (over 40 years); higher HCV RNA viral load; presence of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis; and HCV genotype 1 (2). In patients infected with both HCV and HIV, the progression of liver disease (e.g., fibrosis and cirrhosis) is more rapid, and SVR rates in response to treatment are lower than in patients infected with only HCV (25%–35% overall) (24).

Despite the intuitive value of HCV screening, posttest counseling, and antiviral treatment (29), it remains to be demonstrated that these interventions will result in a reduction in morbidity and mortality from HCV infection. Consequently, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recently recommended against routine HCV screening for asymptomatic high-risk individuals (30). Nonetheless, we contend that psychiatrists should continue to screen patients at risk of HCV and to provide infected patients with counseling, medical evaluation, and referral for IFN treatment (9, 31).

Psychiatric illness and hepatitis C

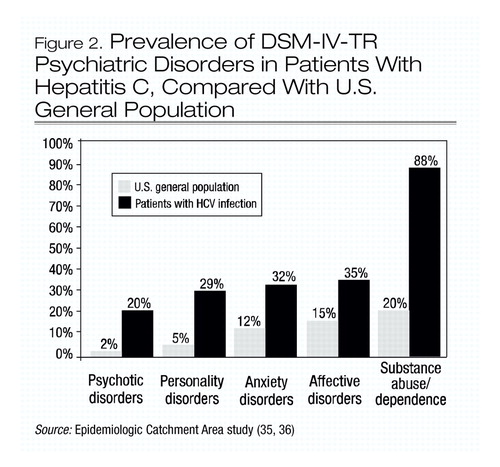

A growing body of evidence suggests that patients infected with HCV have a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders (32–34). At least 50% of patients infected with HCV suffer from one psychiatric illness, and the lifetime prevalence of psychotic, anxiety, affective, personality, and substance use disorders are all higher in the HCV-positive population (32, 33) than in the general U.S. population (35, 36) (Figure 2).

The extent to which psychiatric illness predisposes individuals to HCV infection and the extent to which HCV infection contributes to psychiatric illness are unknown. For some patients with preexisting mental illnesses such as psychotic or affective disorders, high-risk behavior (particularly the sharing of needles, syringes, or intranasal paraphernalia during drug use) clearly increases their risk of contracting HCV infection. However, for other patients, such as those with anxiety and substance use disorders, the distinction between cause and effect is less clear. In any case, for at least 20% of patients with HCV no clear, identifiable mode of transmission can be identified (23).

Hepatitis C in psychiatric populations

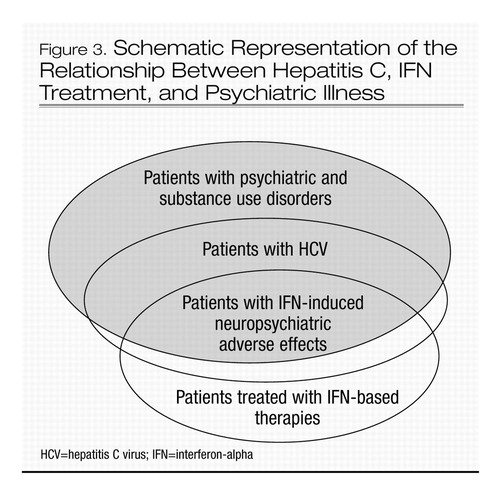

The prevalence of HCV among patients with severe mental illness is four to nine times (8%–18%) that of the general U.S. population (2%). The Five-Site Health and Risk Study found the prevalence of HCV infection among patients in psychiatric hospitals to be 18% (11). In another study the prevalence of HCV infection among patients admitted to a state psychiatric hospital was found to be 8.5% (14). Despite the association between HCV infection and psychiatric hospitalization, screening for HCV has not been routine practice in patients with psychiatric illness (31). This patient population is at risk of contracting HCV by engaging in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., multiple partners, men having sex with men) and intranasal drug use but may not be forthcoming about these activities (22). Therefore, the only reliable way to rule out HCV infection would be to use screening. For example, the CDC has recommended routine HCV screening of incarcerated individuals (37). Routine screening is also recommended for all patients who are found to be infected with HIV (22). Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the relationship between HCV infection, treatment, and psychiatric illness.

Hepatitis C treatment and neuropsychiatric adverse effects

The therapeutic use of IFN is associated with frequent neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including affective, cognitive, and neurovegetative symptoms, that may compromise the management of HCV patients with and without a history of psychiatric illness (38). HCV patients who are treated with IFN are at substantial risk of IFN-induced depression (the incidence is 20%–30%) (39, 40) and other neuropsychiatric adverse effects that can reduce treatment adherence, require a reduction of the dose of the dose of IFN or discontinuation of IFN therapy (41), and reduce the patient’s quality of life (42). Nonetheless, recent studies (39, 40) confirm that up to 30% of patients with preexisting psychiatric illness can complete their IFN treatment course without any significant worsening of their psychiatric symptoms. While one-third of patients undergoing IFN therapy experience depression (43) and one-third suffer no neuropsychiatric symptoms (39, 40, 44), the remaining 30%–40% experience of variety of neuropsychiatric adverse effects that can be managed if identified early. Such adverse effects include a wide range of somatic and neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as fatigue, amotivation, apathy, lack of concentration, irritability, anger, and perceptual, cognitive, and affective symptoms.

Several risk factors are thought to increase the probability of developing psychiatric comorbidity during IFN treatment (45): a history of psychiatric illness (40, 46); a history of substance abuse (47); a family history of psychiatric illness (48); and a history of suicidal ideation (40). Although these factors are not well validated, they were used as exclusion criteria in several large HCV treatment clinical trials (27, 49).

Although the incidence, phenomenology, psychiatric workup, and clinical management of preexisting and IFN-induced depression in HCV patients treated with IFN has been well described (40), considerably less attention has been given to the interplay between HCV, other psychiatric disorders, and IFN (40, 41). Table 3 summarizes the current knowledge about the use of psychotropic medications in patients with HCV undergoing IFN therapy.

Should psychiatric patients with HCV be treated with IFN?

Clinicians remain hesitant to initiate IFN treatment in HCV patients with psychiatric illness because of concerns about precipitating or worsening psychiatric symptoms (67). The practice of excluding patients with psychiatric illness from HCV treatment clinical trials is itself stigmatizing and can result in substantial morbidity and mortality for a vulnerable population (68).

The management of patients with HCV infection who have psychiatric illness also poses unique challenges because psychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers) are metabolized by the liver and can be hepatotoxic. The combination of HCV-induced liver disease, alcohol use, and psychotropic drugs may hasten the progression to cirrhosis. Patients with HCV and psychiatric illness who progress to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease may also be less likely to receive a liver transplant because of the perceived difficulties they might have adhering to the rigorous posttransplant regimen.

With the exception of a few recent studies on the use of IFN in patients with substance use disorders (47, 69, 70), there is relatively little information on the use of IFN in HCV patients with comorbid psychiatric illness such as affective, anxiety, and psychotic disorders (71). The published SVR rates referred to earlier (27, 49) may not be applicable to patients with HCV and psychiatric illness given the exclusion of patients with any history of psychiatric illness or substance abuse from most large HCV treatment trials. Consequently, there is a pressing need to develop improved therapeutic and management approaches to ensure that patients with HCV and comorbid psychiatric illness complete a full, uninterrupted course of IFN treatment.

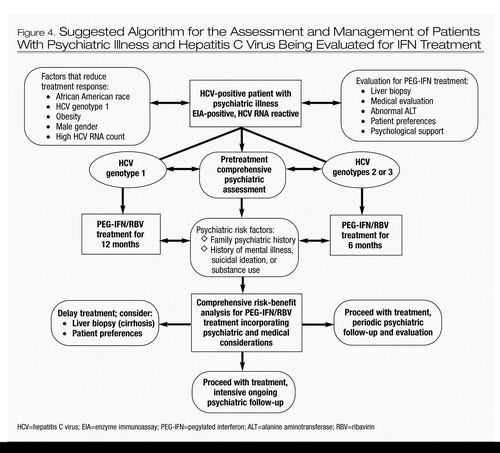

The risk-benefit analysis for an HCV patient with evidence of liver cirrhosis and psychiatric illness may justify IFN treatment. Furthermore, patients with psychiatric illness who receive IFN treatment without achieving SVR may achieve normalization of liver function tests and improvement in liver pathology. However, long-term follow-up studies are needed to determine whether this benefit for IFN nonresponders would translate into a reduction in the incidence of liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. If such a benefit is confirmed, it would strengthen the argument for treating patients with HCV and psychiatric illness with IFN. Figure 4 presents a comprehensive risk-benefit assessment process for patients with HCV and psychiatric illness.

Evidence-based patient selection is paramount when attempting to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with IFN treatment of HCV patients with comorbid psychiatric illnesses. Despite the absence of a consensus on when IFN treatment should be withheld (because of the low estimated likelihood of SVR and/or the high probability of associated psychiatric morbidity), clinicians must undertake an individualized and balanced risk-benefit analysis for each patient before offering IFN treatment, incorporating not only factors specific to HCV disease and the potential for psychiatric complications but also the patient’s preferences and the psychosocial support available.

| Demographic Group | Prevalence (%) | Range (%) | % of U.S. Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| General population | 1.8 | 1.5–2.3 | — |

| Intravenous drug users | |||

| Current drug use | 79 | 72–86 | 0.5 |

| History of drug use | 20 | 10–35 | 5 |

| Noninjection drug use (nasal, smoking) | 10 | 8–25 | 4 |

| Attending substance abuse treatment | 20 | 15–35 | 3 |

| Persons with multiple sex partners | |||

| Number of lifetime partners | |||

| >50 | 9 | 6–16 | 4 |

| 10–49 | 3 | 3–4 | 22 |

| 2–9 | 2 | 1–2 | 52 |

| Men having sex with men | 4 | 2–18 | 5 |

| Military personnel | 0.6 | 0.4–0.8 | 0.5 |

| Veterans treated in VA hospitals | 5.5 | 4–18 | 9 |

| Persons with abnormal liver function tests | 15 | 10–18 | 5 |

| Patients in psychiatric hospitals | 17 | 8–20 | 2 |

| Persons in correctional facilities | 15 | 10–25 | 1 |

| Offer HIV testing and pretest counseling for HIV |

| Avoid sharing toothbrushes, utensils, and dental or shaving equipment, and cover any bleeding wound |

| Be vaccinated against hepatitis A and hepatitis B if not already immune |

| Stop using illicit drugs and/or alcohol; those who continue intravenous drug use should avoid sharing or reusing needles or syringes |

| Do not donate blood, organs, or semen |

| Use safe sexual practices (particularly barrier protection), although the risk of transmission between long-term sexual partners is low (no recommendation to use barrier protection between long-termmonogamous partners) |

| Major depressive disorder: first-line agents are SSRIs for prophylaxis and treatment of depression |

| Prophylaxis |

| Citalopram: proven efficacy in placebo-controlled trial (39) |

| Paroxetine: proven efficacy in placebo-controlled trial (50, 51) |

| Treatment |

| Citalopram: proven efficacy in open trial (52) |

| Paroxetine: proven efficacy in open trial (53) |

| Only case reports to suggest efficacy for fluoxetine (54), sertraline (55–57), and mirtazapine (58) |

| No available evidence for other antidepressants |

| Bipolar disorder: mood stabilizers can be used |

| Lithium: no available evidence but presumed to be safe in patients with HCV because of renal clearance |

| Disodium valproate: careful monitoring of liver function (59) |

| Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine: contraindicated because of risk of agranulocytosis and bone marrow suppression with IFN use |

| Gabapentin: use adjunctively; presumed to be safe in patients with HCV because of renal clearance |

| Psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder) |

| Haloperidol: no available evidence, presumed to be safe in patients with HCV |

| Risperidone: use with caution given reports of risperidone-induced hepatotoxicity (60) |

| Olanzapine: use with caution given elevated risk of diabetes mellitus |

| Quetiapine: no available evidence, presumed to be safe in patients with HCV |

| Clozapine: contraindicated because of risk of agranulocytosis (61) |

| Substance use disorders |

| Disulfiram: use careful monitoring of liver function tests (62) |

| Naltrexone: use careful monitoring of liver function tests (63) |

| Methadone: use careful monitoring of liver function tests (47, 63) |

| Nonspecific neuropsychiatric symptoms |

| Zolpidem: presumed to be safe in patients with HCV (58) |

| Zaleplon: presumed to be safe in patients with HCV (58) |

| Trazodone: use caution given reports of trazodone-induced hepatotoxicity (64, 65). |

| Atomoxetine: use with caution; adjust dose and monitor liver function tests (66) |

| Modafinil: no available evidence, presumed to be safe in patients with HCV |

Figure 1. Hepatitis C Screening Algorithm

HCV=hepatitis C virus; IV=intravenous; EIA=enzyme immunoassay; PCR=polymerase chain reaction

Figure 2. Prevalence of DSM-IV-TR Psychiatric Disorders in Patients With Hepatitis C, Compared With U.S. General Population

Figure 3. Schematic Representation of the Relationship Between Hepatitis C, IFN Treatment, and Psychiatric Illness

HCV=hepatitis C virus; IFN=interferon-alpha

Figure 4. Suggested Algorithm for the Assessment and Management of Patients With Psychiatric Illness and Hepatitis C Virus Being Evaluated for IFN Treatment

HCV=hepatitis C virus; EIA=enzyme immunoassay; PEG-IFN=pegylated interferon; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; RBV=ribavirin

1 Williams I: Epidemiology of hepatitis C in the United States. Am J Med 1999; 107(suppl 6):2–9Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Strader D, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB: Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology 2004; 39:1147–1171Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, Kaslow RA, Margolis HS: The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:556–562Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Lauer GM, Walker BD: Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:41–52Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Alter MJ: Prevention of spread of hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36(5B):S93–S98Crossref, Google Scholar

6 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of hepatitis C: 2002. Hepatology 2002; 36(5B):S3–S20Google Scholar

7 Davis GL: Hepatitis C virus genotypes and quasispecies. Am J Med 1999; 107(suppl 6B):21–26Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Alter MJ: Epidemiology of hepatitis C. Hepatology 1997; 26(S3):62S–65SCrossref, Google Scholar

9 Seeff LB: Natural history of hepatitis C. Am J Med 1999; 107(6 suppl 2):10–15Google Scholar

10 Himelhoch S: Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1426–1427; author reply 1427–1428Google Scholar

11 el-Serag HB: Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 2001; 5:87–107, viCrossref, Google Scholar

12 Alter MJ, Seeff LB, Bacon BR, Thomas DL, Rigsby MO, Di Bisceglie AM: Testing for hepatitis C virus infection should be routine for persons at increased risk for infection. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:715–717Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Poynard T, Yuen M-F, Ratziu V, Lung Lai C: Viral hepatitis C. Lancet 2003; 362(9401):2095–2100Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Osher FC, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, Rosenberg SD; the Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee: Blood-borne infections and persons with mental illness: substance abuse and the transmission of hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:842–847Crossref, Google Scholar

15 McMahon JM, Tortu S: A potential hidden source of hepatitis C infection among noninjecting drug users. J Psychoactive Drugs 2003; 35:455–460Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Rifai MA, Moles JK, Van Der Linden BJ: Hepatitis C screening in patients with substance abuse/dependence disorders. Psychosomatics 2004; 45:159–160Google Scholar

17 Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T: Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:172–174Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Sloan KL: Hepatitis C tested prevalence and comorbidities among veterans in the US northwest. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 38:279–284Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Cheung RC: Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in American veterans. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95:740–747Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctinal settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003; 52(RR-1)Google Scholar

21 Herrine SK: Approach to the patient with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:747–757Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Alter MJ, Kuhnert WL, Finelli L: Guidelines for laboratory testing and result reporting of antibody to hepatitis C virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003; 52(RR-3):1–13, 15Google Scholar

23 Flamm SL: Chronic hepatitis C virus infection. JAMA 2003; 289:2413–2417Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL: Hepatitis C in the HIV-infected person. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:197–207Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Peters MG, Terrault NA: Alcohol use and hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36:S220–S225Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Lieber CS: Hepatitis C and alcohol. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003; 36:100–102Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL Jr, Haussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D, Craxi A, Lin A, Hoffman J, Yu J: Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:975–982Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H Jr, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M, Zeuzem S, Pockros PJ, Lin A, Ackrill AM: Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:346–355Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Chou R, Clark EC, Helfand M: Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: a review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:465–479Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Calonge N, Randhawa G: The meaning of the US Preventive Services Task Force grade I recommendation: screening for hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:718–719Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Rifai MA: Hepatitis C patients with psychiatric illness: the forgotten. Ann Intern Med 2004; electronic letter, available at http://www.annals.org/cgi/eletters/141/9/715Google Scholar

32 Yovtcheva SP, Rifai MA, Moles JK, van der Linden BJ: Psychiatric comorbidity among hepatitis C–positive patients. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:411–415Crossref, Google Scholar

33 el-Serag HB, Kunik M, Richardson P, Rabeneck L: Psychiatric disorders among veterans with hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology 2002; 123:476–482Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Lehman CL, Cheung RC: Depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and alcohol-related problems among veterans with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2640–2646Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85–94Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Norquist GS, Regier DA: The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders and the de facto mental health care system. Annu Rev Med 1996; 47:473–479Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Allen SA, Spaulding AC, Osei AM, Taylor LE, Cabral AM, Rich JD: Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in a state correctional facility. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:187–190Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Dieperink E, Willenbring M, Ho SB: Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with hepatitis C and interferon alpha: a review. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:867–876Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Hauser P, Khosla J, Aurora H, Laurin J, Kling MA, Hill J, Gulati M, Thornton AJ, Schultz RL, Valentine AD, Meyers CA, Howell CD: A prospective study of the incidence and open-label treatment of interferon-induced major depressive disorder in patients with hepatitis C. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7:942–947Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Dieperink E, Ho SB, Thuras P, Willenbring ML: A prospective study of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with interferon-alpha-2b and ribavirin therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C. Psychosomatics 2003; 44:104–112Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Kraus MR, Schafer A, Faller H, Csef H, Scheurlen M: Psychiatric symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving interferon alfa-2b therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:708–714Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Forton DM, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thomas HC: Reduced quality of life in hepatitis C: is it all in the head? J Hepatol 2002; 36:435–438Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Loftis JM, Hauser P: The phenomenology and treatment of interferon-induced depression. J Affect Disord 2004; 82:175–190Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Mulder RT, Ang M, Chapman B, Ross A, Stevens IF, Edgar C: Interferon treatment is not associated with a worsening of psychiatric symptoms in patients with hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 15:300–303Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Fried MW: Side effects of therapy of hepatitis C and their management. Hepatology 2002; 36(5 suppl 1):S237–S244Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Schaefer M, Schmidt F, Folwaczny C, Lorenz R, Martin G, Schindlbeck N, Heldwein W, Soyka M, Grunze H, Koenig A, Loeschke K: Adherence and mental side effects during hepatitis C treatment with interferon alfa and ribavirin in psychiatric risk groups. Hepatology 2003; 37:443–451Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Van Thiel DH, Anantharaju A, Creech S: Response to treatment of hepatitis C in individuals with a recent history of intravenous drug abuse. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:2281–2288Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Capuron L, Hauser P, Hinze-Selch D, Miller AH, Neveu PJ: Treatment of cytokine-induced depression. Brain Behav Immun 2002; 16:575–580Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M-H, Albrecht JK: Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon-alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001; 358(9286):958–965Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Musselman DL, Lawson DH, Gumnick JF, Manatunga AK, Penna S, Goodkin RS, Greiner K, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH: Paroxetine for the prevention of depression induced by high-dose interferon alfa. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:961–966Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Kraus MR, Schafer A, Scheurlen M: Paroxetine for the prevention of depression induced by interferon alfa. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:375–376Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Gleason OC, Yates WR, Isbell MD, Philipsen MA: An open-label trial of citalopram for major depression in patients with hepatitis C. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:194–198Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Kraus MR, Schafer A, Faller H, Csef H, Scheurlen M: Paroxetine for the treatment of interferon-alpha-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16:1091–1099Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Levenson JL, Fallon HJ: Fluoxetine treatment of depression caused by interferon-alpha. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:760–761Google Scholar

55 Dieperink E, Ho SB, Tetrick L, Thuras P, Dua K, Willenbring ML: Suicidal ideation during interferon-alpha2b and ribavirin treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004; 26:237–240Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Lang JP, Meyer N, Doffoel M: [Benefits of a preventive psychiatric accompaniment in patients hepatitis C virus seropositive (HCV): prospective study concerning 39 patients.] Encephale 2003; 29(4 pt 1):362–365 (French)Google Scholar

57 Schramm TM, Lawford BR, Macdonald GA, Cooksley WG: Sertraline treatment of interferon-alfa-induced depressive disorder. Med J Aust 2000; 173:359–361Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Schafer M, Schwaiger M: [Incidence, pathoetiology, and treatment of interferon-alpha induced neuro-psychiatric side effects.] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2003; 71:469–476 (German)Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Felker BL, Sloan KL, Dominitz JA, Barnes RF: The safety of valproic acid use for patients with hepatitis C infection. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:174–178Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Benazzi F: Risperidone-induced hepatotoxicity. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998; 31:241Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Schafer M, Schmidt F, Grunze H, Laakmann G, Loeschke K: [Interferon alpha-associated agranulocytosis during clozapine treatment. Case report and status of current knowledge.] Nervenarzt 2001; 72:872–875 (German)Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Martin B, Alfers J, Kulig C, Clapp L, Bialkowski D, Bridgeford D, Beresford TP: Disulfiram therapy in patients with hepatitis C: a 12-month, controlled follow-up study. J Stud Alcohol 2004; 65:651–657Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Lozano Polo JL, Gutierrez Mora E, Martinez Perez V, Santamaria Gutierrez J, Vada Sanchez J, Vallejo Correas JA: [Effect of methadone or naltrexone on the course of transaminases in parenteral drug users with hepatitis C virus infection.] Rev Clin Esp 1997; 197:479–483 (Spanish)Google Scholar

64 Fernandes NF, Martin RR, Schenker S: Trazodone-induced hepatotoxicity: a case report with comments on drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95:532–535Google Scholar

65 Rettman KS, McClintock C: Hepatotoxicity after short-term trazodone therapy. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35:1559–1561Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Chalon SA, Desager J-P, DeSante KA, Frye RF, Witcher J, Long AJ, Sauer J-M, Golnez J-L, Smith BP, Thomasson HR, Horsmans Y: Effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of atomoxetine and its metabolites. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003; 73:178–191Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Rifai MA, Bozorg B, Rosenstein DL: Interferon for hepatitis C patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2331–2332Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Davis GL, Rodrigue JR: Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in active drug users. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:215–217Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Van Thiel DH, Friedlander L, De Maria N, Molloy PJ, Kania RJ, Colantoni A: Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in individuals with pre-existing or confounding neuropsychiatric disease. Hepatogastroenterology 1998; 45:328–330Google Scholar

70 Van Thiel DH, Friedlander L, Molloy PJ, Fagiuoli S, Kania RJ, Caraceni P: Interferon-alpha can be used successfully in patients with hepatitis C virus–positive chronic hepatitis who have a psychiatric illness. Eur J Gastroenterol and Hepatol 1995; 7:165–168Google Scholar

71 Strader D: Understudied populations with hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36(5 suppl 1):S226–S236Crossref, Google Scholar