Monitoring the Future: National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings

This report presents an overview of the key findings from the Monitoring the Future study’s 2001 nationwide survey of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students. A particular emphasis is placed on recent trends in the use of licit and illicit drugs. Trends in the levels of perceived risk and personal disapproval associated with each drug—which this study has shown to be particularly important in explaining trends in use—are also presented, as well as trends in perceived availability of the various drugs.

Monitoring the Future (MTF), begun in 1975, is a long-term study of American adolescents, college students, and adults through age 40. It is conducted by the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research and is supported under a series of investigator-initiated, competing research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

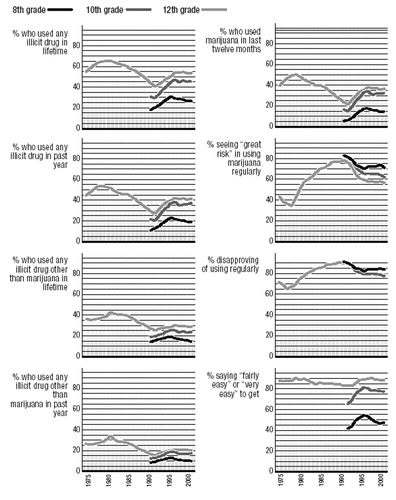

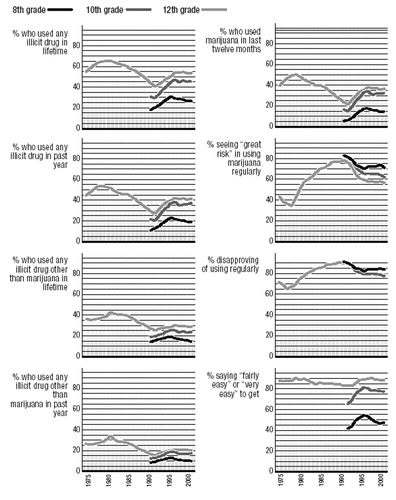

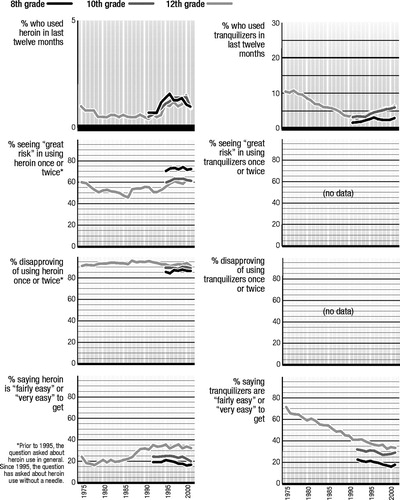

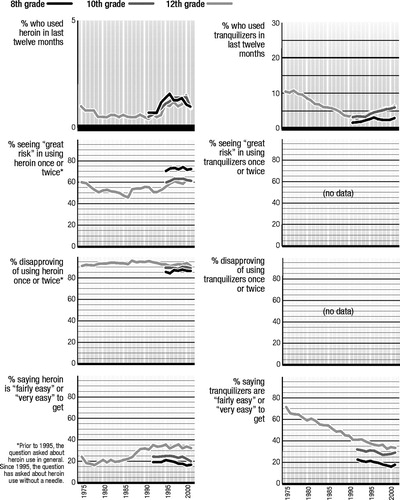

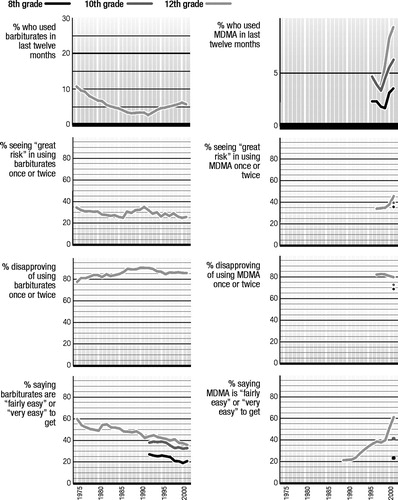

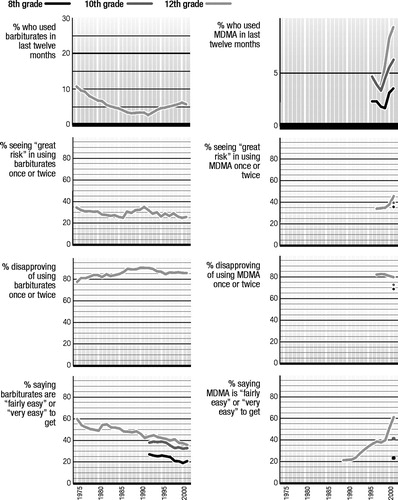

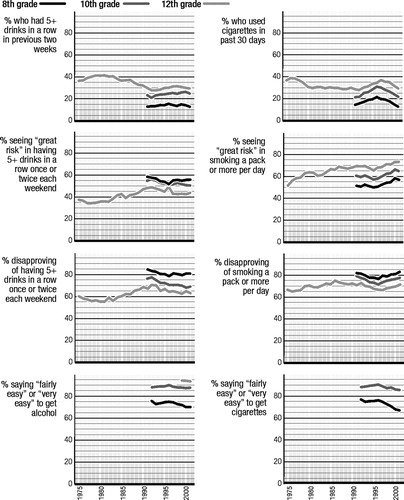

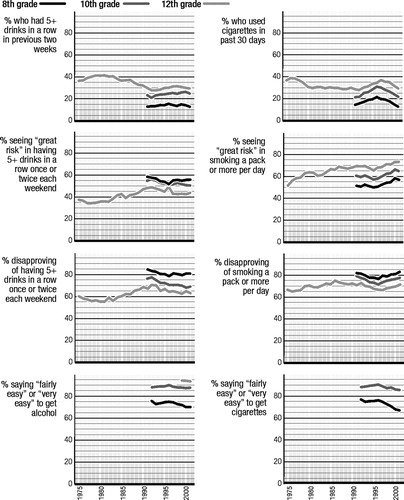

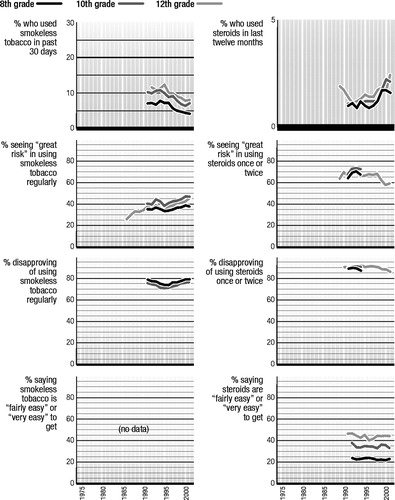

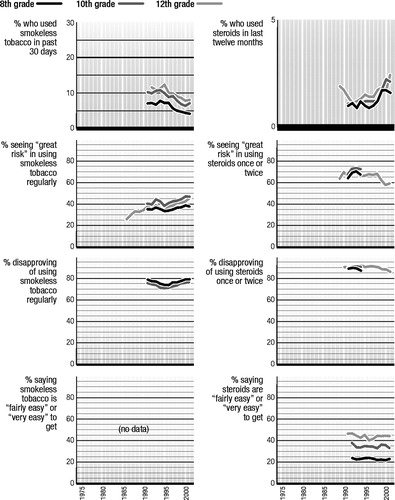

Following this introduction, there is a synopsis of methods used and an overview of the key results from the 2001 survey. This general synopsis is followed by a section for each individual drug class, providing graphs that show trends in the overall proportions of students at each grade level (a) reporting use, (b) seeing a “great risk” associated with its use, (c) disapproving its use, and finally, (d) saying that they could get the drug “fairly easily” or “very easily.” The trends are presented for the interval 1991–2001 for all grades, and for 1975–2001 for the 12th graders.

The tables at the end of [the original] report provide the statistics underlying the graphs; in addition they present data on lifetime, 30-day, and (for selected drugs) daily prevalence. [Prevalence refers to the proportion or percentage of the sample reporting use of the given substance on one or more occasions in a given time interval—e.g., lifetime, past 12 months, or past 30 days. The prevalence of daily use usually refers to use on 20 or more occasions in the past 30 days.] They present these prevalence statistics only for the 1991–2001 interval, but statistics on 12th graders are available for longer intervals in other publications from the study. The tables indicate for each prevalence period which of the one-year changes between 2000–2001 are statistically significant.

A more extensive analysis of the study’s findings on secondary school students may be found in a volume to be published later in 2002. [The most recent publication in this series is: Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG: Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2000: Volume I, Secondary school students. NIH Publication No 01-4924. Bethesda, MD, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2001.] The volumes in this series also contain a more complete description of the study’s methodology as well as an appendix on how to test the significance of differences between groups or for the same group over time. The most recent such volume is always posted on the study’s Web site.

The study’s findings on American college students and young adults are not covered in this early Overview report because the 2001 data are not available at the time of this writing. They are covered in a second series of volumes that will be updated later this year. [The most recent in this series is: Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG: Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2000: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–40. NIH Publication No 01-4925. Bethesda, MD, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2001. It may be ordered from the National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information; or it may be viewed on the study’s Web site at www.monitoringthefuture.org.] Volumes in these two annual series are available from the National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information at (800) 729-6686 or by e-mail at [email protected].

Further information on the study, including its latest press releases, a listing of all publications, and the text of many of them, may be found on the Web at www.monitoringthefuture.org.

Study design and methods

At the core of Monitoring the Future is a series of large, annual surveys of nationally representative samples of students in public and private secondary schools throughout the coterminous United States. Every year since 1975 a national sample of 12th graders has been surveyed. Beginning in 1991, the study was expanded to include comparable national samples of 8th graders and 10th graders each year.

Sample sizes

The 2001 sample sizes were 16,800, 14,300, and 13,300 in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades, respectively. In all, about 44,300 students in 424 schools participated. Because multiple questionnaire forms are administered at each grade level, and because not all questions are contained in all forms, the number of cases upon which a particular statistic is based can be less than the total sample. The tables at the end of [the original report] contain the sample sizes associated with each statistic.

Field procedures

University of Michigan staff members administer the questionnaires to students, usually in their classrooms during a regular class period. Participation is voluntary. Questionnaires are self-completed and formatted for optical scanning. In 8th and 10th grades the questionnaires are completely anonymous, and in 12th grade they are confidential (to permit the longitudinal follow-up of a random sub-sample of participants for some years after high school in a panel study).

Measures

A standard set of three questions is used to determine usage levels for the various drugs (except for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco). For example, we ask, “On how many occasions (if any) have you used LSD (‘acid’) . . . (a) . . . in your lifetime?, (b) . . . during the past 12 months?, (c) . . . during the last 30 days?” Each of the three questions is answered on the same answer scale: 0 occasions, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–39, and 40 or more occasions. For the psychotherapeutic drugs (amphetamines, barbiturates, tranquilizers, and opiates other than heroin), respondents are instructed to include only use “. . . on your own—that is, without a doctor telling you to take them.” A similar qualification is used in the question on use of anabolic steroids. For cigarettes, respondents are asked two questions about use: “Have you ever smoked cigarettes?” (the answer categories are “never,” “once or twice,” and so on) and “How frequently have you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days?” (the answer categories are “not at all,” “less than one cigarette per day,” “one to five cigarettes per day,” “about one-half pack per day,” etc.). Parallel questions are asked about smokeless tobacco.

Alcohol use is measured using the three questions illustrated above for LSD. A parallel set of three questions asks about the frequency of being drunk. Another question asks, for the prior two-week period, “How many times have you had five or more drinks in a row?” Perceived risk is measured by a question asking, “How much do you think people risk harming themselves (physically or in other ways), if they . . .” “. . . try marijuana once or twice,” for example. The answer categories are “no risk,” “slight risk,” “moderate risk,” “great risk,” and “can’t say, drug unfamiliar.” Disapproval is measured by the question, “Do YOU disapprove of people doing each of the following?” followed by “trying marijuana once or twice,” for example. Answer categories are “don’t disapprove,” “disapprove,” “strongly disapprove,” and (in 8th and 10th grades only) “can’t say, drug unfamiliar.” Perceived availability is measured by the question, “How difficult do you think it would be for you to get each of the following types of drugs, if you wanted some?” Answer categories are “probably impossible,” “very difficult,” “fairly difficult,” “fairly easy,” “very easy” and (in 8th and 10th grades only) “can’t say, drug unfamiliar.”

Overview of key findings

The surveys of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students in the United States conducted in 2001 generated mixed results, as did the 1999 and 2000 surveys.

Drugs increasing in use

The primary drug showing an increase in 2001 was ecstasy (MDMA), which had been rising sharply since 1998. (A similar increase had been documented among the 19- to 26-year-olds in the follow-up surveys in the study, at least through 2000.) While there was further increase in ecstasy use observed in 2001 among the secondary school students, the rate of increase began to fall off, quite possibly due to a sharp increase in the proportion of students seeing this drug as dangerous. [The 2000–2001 increases in use were not statistically significant for individual grades, but were significant across the three grades combined. Thirty-day prevalence showed a less consistent pattern of change this year, possibly reflecting a very recent turnaround in use in 12th grade; but another year of data is needed to clarify this.] The proportion of 12th graders (8th and 10th graders were not asked this question until 2001) saying they see a “great risk” in trying ecstasy jumped 8 percentage points between 2000 and 2001. However, special analyses indicate that the proportion of the schools in the MTF national samples having at least one respondent who has ever used ecstasy was still increasing in 2001. Thus the drug is still diffusing to new communities, which may have been more than enough to offset the effects of the increase in perceived risk. Reported availability of ecstasy continued to rise quite dramatically, perhaps in part due to this diffusion process. The use of anabolic steroids increased significantly among 12th graders this year, perhaps reflecting a cohort effect, since steroid use had risen fairly sharply among the younger students in the prior two years. However, there was no further increase in steroid use among the 8th or 10th graders in 2001.

Drugs declining in use

In contrast to the increase in ecstasy, a number of other drugs showed evidence of some decline in 2001. One of the most important such declines involved heroin, which had been at or near peak levels in recent years, due in large part to the ascent of using heroin without a needle in the early 1990s. Eighth graders showed some decline in heroin use in 2000, and the 10th and 12th graders showed their first decline in use in 2001. Virtually all of this improvement occurred in the use of heroin without a needle (i.e., in smoking or snorting it).

Of clear and particular importance, cigarette smoking by adolescents in all three grades continued to decline sharply in 2001, extending an improvement that began after 1996 (among 8th and 10th graders) or 1997 (among 12th graders). Daily smoking among 8th graders has now fallen almost by half since the recent peak rate in 1996—offsetting the sharp increase in smoking seen in this age group in the early 1990s. A specialized type of flavored cigarette called “bidis,” imported from India, threatened to make inroads into the American market. However, the use of these cigarettes, which was not very widespread in 2000—the first year on which we had prevalence estimates—actually declined appreciably in 2001. The third class of tobacco product on which we have estimates is smokeless tobacco, the use of which had declined considerably in recent years, but did not decline any further in 2001.

Some of the illicit drugs other than heroin showed continuing declines in 2001, though many of those were gradual and did not reach statistical significance for the one-year interval of 2000–2001. These included LSD, the annual prevalence of which dropped significantly in 10th grade and nonsignificantly in 8th grade in 2001. (There was no further change in 12th grade.) All three grades have annual prevalence rates of LSD use that are now 25% to 41% lower than the recent peak in 1996; these represent important cumulative declines. Somewhat surprisingly, these declines have not been accompanied by increases in perceived risk, leading us to conclude that another drug may be displacing LSD as a drug of choice. Ecstasy seems the most likely candidate, since it is also used for its hallucinogenic effects and is the only drug on the rise at present. In fact, the perceived risk of LSD use actually has been falling (as has the disapproval of its use, especially among 8th graders), and this may be setting the stage for a comeback of LSD use at some future time.

Inhalant use, which began to decline from peak levels in 1996 in all three grades, continued to decline in 2001 (though only the 12th grade one-year decline was statistically significant). The annual prevalence rates for inhalants are now down from their 1995 peaks by 29%, 31%, and 44% in grades 8, 10, and 12, respectively. Again, these are important cumulative improvements.

The use of crack and powdered cocaine are both off modestly from their peak levels in the 1990s (which were far below the peak levels reached in the mid-1980s); but only cocaine powder showed a significant decline in 2001 (only in 10th grade).

There has been some modest decrease in the 30-day prevalence of alcohol use among students at all three grades since the recent peaks reached in 1996 or 1997, though neither the increase before the peak nor the decrease thereafter has amounted to much change. The gradual decreases continued this year, though none reached statistical significance. Reports of being drunk also declined in grades 8 and 10 this year.

Drugs holding steady

The use of marijuana held steady at rates only slightly below the peak rates reached in 1997 among 10th and 12th graders. Eighth graders, who had shown a slow steady decline in marijuana use after their recent peak in 1996, also showed no further improvement this year. Because marijuana use remained unchanged, so did the index of the use of any illicit drug, which is driven mostly by marijuana—the most prevalent of the illicit drugs.

Other drugs that showed no systematic changes in 2001, in addition to marijuana, were hallucinogens other than LSD, narcotics other than heroin (reported only for 12th graders), heroin with a needle, amphetamines, methamphetamine, crystal methamphetamine, barbiturates (reported only for 12th graders), and three of the so-called “club drugs”—Rohypnol, GHB, and Ketamine.

It is noteworthy that the downturns in the 1990s started first and have been the most sustained among the 8th graders for a number of drugs.

Reasons for the diverging trends

The wide divergence in the trajectories of the different drugs in this single year helps to illustrate the point that, to a considerable degree, the determinants of use are often specific to the drugs. These determinants include both the perceived benefits and the perceived risks that young people come to associate with each drug.

Unfortunately, word of the supposed benefits of using a drug usually spreads much faster than information about the adverse consequences. The former takes only rumor and a few testimonials, the spread of which has been hastened greatly by the electronic media and the Internet. The latter—the perceived risks—usually take much longer for the evidence (e.g., of death, disease, overdose reactions, addictive potential) to cumulate and then to be disseminated. Thus, when a new drug comes onto the scene, it has a considerable “grace period” during which its benefits are alleged and its consequences are not yet known. We have argued that ecstasy has been the beneficiary of such a grace period until this year, when perceived risk for this drug finally rose sharply.

Implications for prevention

To some considerable degree, prevention must occur drug by drug, because knowledge of the adverse consequences of one drug will not necessarily generalize to the use of other drugs. Many of young people’s beliefs and attitudes are specific to the drug. A review of the charts in this [overview] on perceived risk and disapproval for the various drugs—attitudes and beliefs which we have shown to be important in explaining many drug trends over the years—will amply illustrate this contention. These attitudes and beliefs are at quite different levels for the various drugs and, more importantly, often trend differently over time.

New drugs help to keep the epidemic going

Another point well illustrated by this year’s results is the continuous flow of new drugs introduced onto the scene or of older ones being “rediscovered” by young people. Many drugs have made a comeback years after they first fell from popularity, often because young people’s knowledge of their adverse consequences faded as generational replacement took place. We call this process “generational forgetting.” Examples of this include LSD and methamphetamine, two drugs used widely in the beginning of the broad epidemic of illicit drug use, which originated in the 1960s. Heroin, cocaine, PCP, and crack are some others that made a comeback in the 1990s after their initial popularity faded.

As for newer drugs coming onto the scene, examples include the nitrite inhalants and PCP in the 1970s, crack and crystal methamphetamine in the 1980s, and Rohypnol, GHB, and ecstasy in the 1990s. The perpetual introduction of new drugs (or of new forms of taking older ones, as illustrated by crack, crystal methamphetamine, and non-injected heroin) helps to keep the country’s “drug problem” alive. Because of the lag times described previously, during which evidence of adverse consequences must cumulate and be disseminated before they begin to deter use, the forces of containment are always playing “catch up” with the forces of encouragement and exploitation.

Where are we now?

As the country begins the 21st century, clearly the problems of substance abuse remain widespread among American young people. Today over half (54%) have tried an illicit drug by the time they finish high school. Indeed, if inhalant use is included in the definition of an illicit drug, more than a third (35%) have done so as early as 8th grade—when most students are only 13 or 14 years old. Three out of ten (29%) have used some illicit drug other than marijuana by the end of 12th grade, and two of those three (20% of all 12th graders) have done so in just the 12 months prior to the survey.

Cigarettes and alcohol

The statistics for use of the licit drugs, cigarettes and alcohol, are also a basis for considerable concern. Nearly two-thirds (61%) of American young people have tried cigarettes by 12th grade, and almost a third (30%) of 12th graders are current smokers. Even as early as 8th grade, nearly four in every ten students (37%) have tried cigarettes, and one in eight (12%) already has become a current smoker. Fortunately, we have seen some real improvement in these smoking statistics over the last four or five years, following a dramatic increase in these rates earlier in the 1990s.

Cigarette use reached its recent peak in 1996 at grades 8 and 10, capping a rapid climb of some 50% from the 1991 levels (when data first were gathered on these grades). Since 1996, current smoking in these grades has fallen off considerably (by 42% and 30%, respectively), including the further decline in 2001. In 12th grade, peak use occurred a year later (1997), from which there has been a more modest decline of 19%. Overall increases in perceived risk and disapproval of smoking appear to be contributing to this downturn. (See the section on cigarettes for more detail.)

Smokeless tobacco use has also been in decline in recent years. Concentrated among males, like steroid use, it has shown fair proportional declines.

Alcohol use remains extremely widespread among today’s teenagers. Four out of every five students (80%) have consumed alcohol (more than just a few sips) by the end of high school; and about half (51%) have done so by 8th grade. In fact, nearly two-thirds (64%) of the 12th graders and nearly a quarter (23%) of the 8th graders in 2001 report having been drunk at least once in their life. To a considerable degree, alcohol trends have tended to parallel the trends in illicit drug use. These trends include some modest increase in binge drinking (defined as having five or more drinks in a row at least once in the past two weeks) in the early part of the 1990s, but a proportionally smaller increase than was seen for most of the illicit drugs. Fortunately, binge drinking rates leveled off three or four years ago, just about when the illicit drugs began to turn around.

Any illicit drug use

In the remainder of this report, separate sections are provided for each of the many classes of illicit drugs, but we begin by considering the proportions of American adolescents who use any illicit drug, regardless of type. Monitoring the Future routinely reports three different indexes of illicit drug use—an index of “any illicit drug use,” an index of the use of “any illicit drug other than marijuana,” and an index of the use of “any illicit drug including inhalants.” In this section we discuss only the first two; the statistics for the third may be found in [Table 1 in the original report; footnote 1 to Tables 1 through 3 provides the exact definition of “any illicit drug”].

In order to make comparisons over time, we have kept the definitions of these indexes constant, even though some new substances appear as time passes. The index levels would be little affected by the inclusion of these new substances, however, prim-arily because almost all users of them are also using the more prevalent drugs included in the indexes. The major exception has been inhalants, the use of which is quite prevalent in the lower grades. Thus, after the lower grades were added to the study in 1991, a special index was added that includes inhalants.

Trends in use

In the last third of the twentieth century, young Americans achieved extraordinary levels of illicit drug use, either by historical comparisons in this country or by international comparisons with other countries. The trends in lifetime use of any illicit drug are given in the first panel (Figure 1)[of the Trends in Illicit Drug Use charts]. [This is the only set of figures in this volume presenting lifetime use statistics. For other drugs, lifetime statistics may be found in the tables at the end of the original report.] By 1975, when the study began, the majority of young people (55%) had used an illicit drug by the time they left high school. This figure rose to two-thirds (66%) by 1981, before a long and gradual decline to 41% by 1992—the low point. Today, the proportion is back to 54%, after a period of considerable rise in the 1990s. The comparable trends for annual, as opposed to lifetime, prevalence appear in the second (upper right) panel. They show a gradual and continuing falloff after 1996 among 8th graders. Peak rates were reached in 1997 in the two upper grades, but there has been no further decline since 1998.

Because marijuana is so much more prevalent than any other illicit drug, trends in its use tend to drive the index of “any illicit drug use.” For this reason we have an index excluding marijuana use, showing the proportion of these populations willing to use the other, so-called “harder,” illicit drugs. The proportions using any illicit drug other than marijuana are in the third panel (lower left). In 1975 over one-third (36%) of 12th graders had tried some illicit drug other than marijuana. This figure rose to 43% by 1981, followed by a long period of decline to a low of 25% in 1992. Some increase followed in the 1990s, as the use of a number of drugs rose steadily, and it reached 30% by 1997. (In 2001 it was 29%.) The fourth panel presents the annual prevalence data for the same index, which shows a pattern of change over the past few years similar to the index of any illicit drug use.

Overall, these data reveal that, while use of individual drugs (other than marijuana) may fluctuate widely, the proportion using any of them is much less labile. In other words, the proportion of students prone to using such drugs and willing to cross the normative barriers to such use changes more gradually. The usage rate for each individual drug, on the other hand, reflects many, more rapidly changing determinants specific to that drug: how widely its psychoactive potential is recognized, how favorable the reports of its supposed benefits are, how risky the use of it is seen to be, how acceptable it is in the peer group, how accessible it is, and so on.

Marijuana

Marijuana has been the most widely used illicit drug for the 26 years of this study. Marijuana can be taken orally, mixed with food, and smoked in a concentrated form as hashish—the use of which is much more common in Europe. However, nearly all the consumption in this country involves smoking it in rolled cigarettes (“joints”), in pipes or, more recently, in hollowed-out cigars (“blunts”).

Trends in use

Annual marijuana use peaked at 51% among 12th graders in 1979, following a rise that began during the 1960s. (Figure 2) Then, use declined fairly steadily for 13 years, bottoming at 22% in 1992—a decline of more than half. The 1990s, however, saw a resurgence of use. After a considerable increase in the 1990s (one that actually began among 8th graders a year earlier than among 10th and 12th graders), annual prevalence rates peaked in 1996 at 8th grade and in 1997 at 10th and 12th grades. There has been some very modest decline since those peak levels, more so among the 8th graders, but no one-year change was significant in either 2000 or 2001.

Perceived risk

The amount of risk associated with using marijuana fell during the earlier period of increased use and again during the more recent resurgence of use in the 1990s. Indeed, at 10th and 12th grades, perceived risk began to decline a year before use began to rise in the upturn of the 1990s, making perceived risk a leading indicator of change in use. (The same may have happened at 8th grade, as well, but we do not have data starting early enough to check that possibility.) The decline in perceived risk halted in 1996 in 8th and 10th grades, and use began to decline a year or two later. Again, perceived risk was a leading indicator of change in use.

Disapproval

Personal disapproval of marijuana use slipped considerably among 8th graders between 1991 and 1996, and among 10th and 12th graders between 1992 and 1997. For example, the proportions of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, respectively, who said they disapproved of trying marijuana once or twice fell by 17, 21, and 19 percentage points over those intervals of decline. Since then there has been some modest increase in disapproval among 8th graders, but not much among 10th and 12th graders.

Availability

Since the study began in 1975, between 83% and 90% of every senior class have said that they could get marijuana fairly easily or very easily if they wanted some; therefore, it seems clear that this has remained a highly accessible drug. Since 1991, when data were also available for 8th and 10th graders, we have seen that marijuana is considerably less accessible to younger adolescents. Still, in 2001 nearly half of all 8th graders (48%) and more than three-quarters of all 10th graders (77%) reported it as being accessible. This compares to 89% for seniors.

As marijuana use rose sharply in the early and mid-1990s, reported availability increased as well, perhaps reflecting the fact that more young people had friends who were users. Availability peaked for 8th and 10th graders in 1996 and has shown some falloff since, particularly in 8th grade. Availability peaked a bit later for 12th graders. There has been no further decline in availability in the last couple of years in the upper grades, nor in 2001 in grade 8.

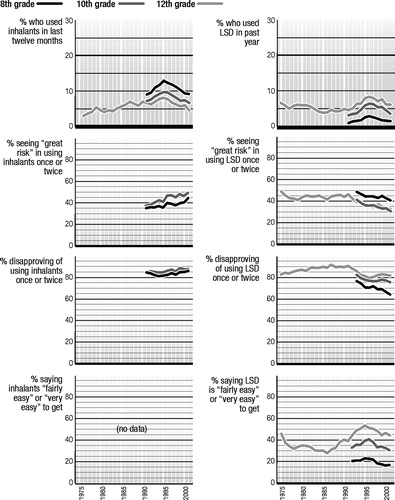

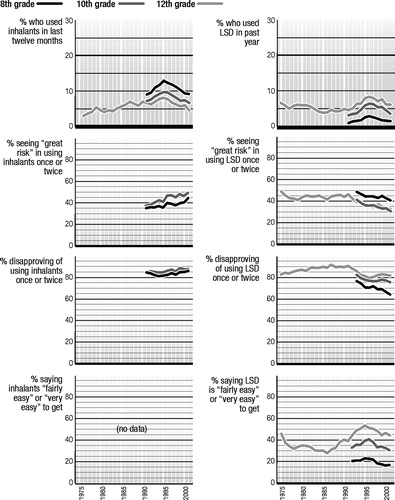

Inhalants

Inhalants are any gases or fumes that can be inhaled for the purpose of getting high. These include many household products, the sale and possession of which is perfectly legal, including such things as airplane glue, nail polish remover, gasoline, solvents, butane, and propellants used in certain commercial products, such as whipped cream dispensers. Unlike nearly all other classes of drugs, their use is most common among younger adolescents and tends to decline as youngsters grow older. The early use of inhalants may reflect the fact that many inhalants are cheap, readily available, and legal. The decline in use with age no doubt reflects their coming to be seen as “kids’ drugs.” In addition, a number of other drugs become available to older adolescents, who also are more able to afford them.

Trends in use

According to the long-term data from 12th graders, inhalant use (excluding the use of nitrite inhalants) rose gradually for some years, from 1976 to 1987. (Figure 3) This rise in use was somewhat unusual in that most other forms of illicit drug use were in decline during the 1980s. Use rose among 8th and 10th graders from the time data were first gathered on them, 1991, through 1995, and also rose among 12th graders from 1992 to 1995. All grades exhibited a steady decline in use through 1999, though it halted briefly at 10th and 12th grades in 2000, before resuming in 2001. In 2001, inhalant use dropped significantly for 12th grade.

Perceived risk

Only 8th and 10th graders have been asked questions about the degree of risk they associate with inhalant use. Relatively low proportions of them think that there is a “great risk” in using an inhalant once or twice, although there was an upward shift in this belief between 1995 and 1996, and again in 2001 when significant increases in perceived risk were seen in both 8th and 10th grades. The Partnership for a Drug-Free America launched an anti-inhalant advertising initiative in 1995, which may help to explain the increase in perceived risk, and the turnaround in use, after that point.

Disapproval

Quite high proportions of students say they would disapprove of even trying an inhalant. There has been a very gradual upward drift in this attitude since 1995.

Availability

Respondents have not been asked about the availability of inhalants. We have assumed that these substances are universally available to young people in these age ranges.

LSD

LSD is the most widely used drug within the larger class of drugs known as hallucinogens. Statistics on overall hallucinogen use, and on the use of hallucinogens other than LSD, may be found in the tables at the end of [the original] report.

Trends in use

The annual prevalence of LSD use has remained below 10% for the last 26 years. (Figure 4) Use had declined some in the first 10 years of the study, likely continuing a decline that had begun before 1975. Use had been fairly level in the latter half of the 1980s but, as was true for a number of other drugs, use rose in all three grades between 1991 and 1996. Annual prevalence at all three grades is now one-quarter to one-third below the peak level reached in 1996. Use continued to drop for the 10th grade in 2001, but leveled in the other grades.

Perceived risk

We think it likely that perceived risk for LSD use had grown in the early 1970s, before this study began, as concerns about possible neurological and genetic effects spread (most of which were never scientifically confirmed), and also as concern about “bad trips” grew. However, there was some decline in perceived risk in the late 1970s. The degree of risk associated with LSD experimentation then remained fairly level among 12th graders through most of the 1980s but began a substantial decline after 1991, dropping 12 percentage points by 1997, before leveling and then dropping slightly after 1998. From the time that perceived risk was first measured among 8th and 10th graders, in 1993, through 1998, perceived risk fell in both of these grades, as well. The fact that use has been declining in recent years, despite a fall in perceived risk, suggests that some mechanism is involved other than a change in underlying attitudes and beliefs. The possibility that another drug might be displacing LSD seems promising, and the most likely candidate would be ecstasy, since it has been rising sharply in popularity and its use is common in some of the same situations as LSD.

Disapproval

Disapproval of LSD use was quite high among 12th graders through most of the 1980s, but began to decline after 1991 along with perceived risk. All three grades exhibited a decline in disapproval through 1996, with disapproval of experimentation dropping a total of 11 percentage points between 1991 and 1996 among 12th graders. After 1996 there emerged a slight increase in disapproval among 12th graders, accompanied by a leveling among 10th graders and some further decline among 8th graders. Since 1999 disapproval of LSD use has declined some in all three grades.

Availability

Reported availability of LSD by 12th graders has varied quite a bit over the years. It fell considerably from 1975 to 1983, remained level for a few years, and then began a substantial rise after 1986, reaching a peak in 1995. LSD availability also rose among 8th and 10th graders in the early 1990s, reaching a peak in 1995 or 1996. Since those peak years, there has been some falloff in availability in all three grades, particularly 12th grade—quite possibly because fewer students have LSD-using friends through whom they could gain access.

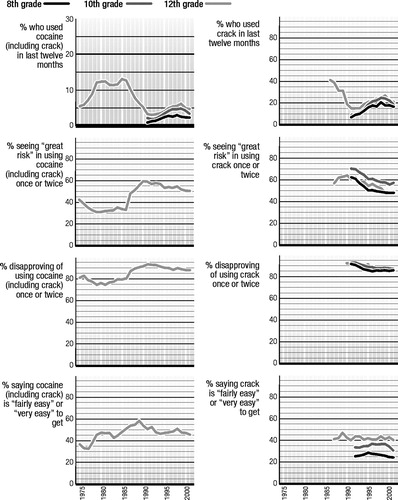

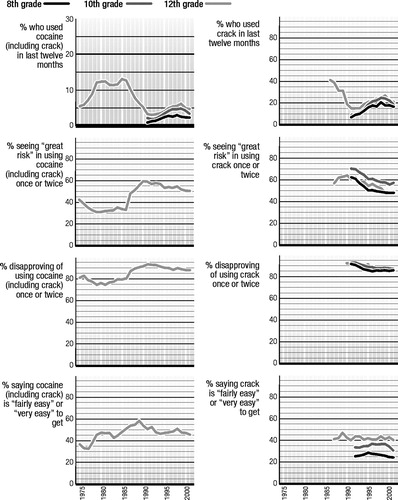

Cocaine

For some years cocaine was used almost exclusively in powder form, though “freebasing” emerged for a while. Then in the early 1980s came the advent of crack cocaine. Our original questions did not distinguish among different forms of cocaine or different modes of administration, but simply asked about using cocaine. The findings contained in this section report on the results of those more inclusive questions asked of 12th graders over the years.

In 1987 we also began to ask separate questions about the use of crack cocaine and “cocaine other than crack,” which was comprised almost entirely of powder cocaine use. Data on these two components of overall cocaine use are contained in the tables in [the original] report, and crack is discussed in the next section.

Trends in use

There have been some important changes in the levels of overall cocaine use (which includes crack) over the life of the study. (Figure 5) Use among 12th graders originally burgeoned in the late 1970s, then remained fairly stable through the first half of the 1980s, before starting a precipitous decline after 1986. Annual prevalence among 12th graders dropped by about three-quarters between 1986, when it was 12.7%, and 1992, when it reached 3.1%. Between 1992 and 1999, use reversed course again and doubled to 6.2%, before declining to 4.8% by 2001. Use also rose in 8th and 10th grades after 1992, before reaching recent peak levels in 1998 and 1999, respectively. In the past 2 to 3 years, use has dropped some in all grades.

Perceived risk

General questions about the dangers of cocaine and disapproval of cocaine have been asked only of 12th graders. The results tell a fascinating story. They show that perceived risk for experimental use fell in the late 1970s (when use was rising), stayed level in the first half of the 1980s (when use was level), and then jumped very sharply in a single year (by 14 percentage points between 1986 and 1987), just when the substantial decline in use began. The year 1986 was marked by a national media frenzy over crack cocaine, and also by the widely publicized cocaine-related death of Len Bias, a National Basketball Association first-round draft pick. Bias’ death was originally reported as resulting from his first experience with cocaine. Though that later turned out not to be the case, the message had already “taken.” We believe this event helped to persuade many young people that use of cocaine at any level, no matter how healthy the individual, was dangerous. Perceived risk continued to rise through 1990, and the fall in use continued. Perceived risk began to decline after 1991, and use began a long rise a year later. Although cocaine use has declined in recent years, perceived risk has continued to fall gradually—but leveled for crack and cocaine powder, specifically.

Disapproval

Disapproval of cocaine use by 12th graders followed a cross-time pattern similar to that for perceived risk, although its 7 percentage-point jump in 1987 was not quite so pronounced. There was some decline from 1991 to 1997, but fair stability since then, despite the decline in perceived risk.

Availability

The proportion of 12th graders saying that it would be “fairly easy” or “very easy” for them to get cocaine if they wanted some was 33% in 1977, rose to 48% by 1980, held fairly level through 1985, increased further to 59% by 1989 (in a period of rapidly declining use), and then fell back to about 49% by 1993. Since then, perceived availability has remained fairly steady. Note that the pattern of change does not map all that well onto the patterns of change in actual use, suggesting that changes in overall availability may not have been a major determinant of use—particularly of the sharp decline in use in the late 1980s. The advent of crack cocaine in the early 1980s, however, provided a lower-cost form of cocaine, thus reducing the prior social class differences in use (documented in our other publications).

Crack Cocaine

Note: The distinction between crack cocaine and other forms of cocaine (mostly powder) was not made until the middle of the life of the study. The charts on [crack use] begin their trend lines when these distinctions were introduced for the different types of measures. Charts are not presented here for the “other forms of cocaine” measures, simply because the trend curves look extremely similar to those for crack. (All the statistics are contained in the tables [at the end of the original report].) The absolute levels of use, risk, etc., are somewhat different, but the trends are very similar. Usage levels tend to be higher for cocaine powder compared to crack, the levels of perceived risk a bit lower, while disapproval and availability are quite close for the two different forms of cocaine.

Several indirect indicators in the study suggested that crack use grew rapidly in the period 1983–1986, starting before we had direct measures of crack use. (Figure 6) In 1986 we asked a single usage question in one of the five questionnaire forms given to 12th graders: those who indicated any cocaine use in the prior 12 months were asked if they had used crack. The results from that question represent the first data point in the first panel [in the charts on crack use]. After that, our usual set of three questions about use was asked about crack and was inserted into several questionnaire forms.

Trends in use

After 1986 there was a precipitous drop in crack use among 12th graders—one that continued through 1991. After 1991, all three grades showed a slow and steady increase in use through 1998. Indeed, crack was one of the few drugs still increasing in use in 1998. In 1999, crack use finally started to drop in 8th and 10th grades. The recent peak in 12th grade was reached in 1999 (2.7%), but there was a significant drop to 2.1% by 2001.

Perceived risk

By the time we added questions about the perceived risk of using crack in 1987, it was already seen as one of the most dangerous of all the illicit drugs by 12th graders: 57% saw a great risk in even trying it. This compared to 54% for heroin, for example. (See the previous section on cocaine for a discussion of changes in perceived risk in 1986.) Perceived risk for crack rose still higher through 1990, reaching 64% of 12th graders who said they thought there was a great risk in taking crack once or twice. (Use was dropping during that interval.) After 1990 some falloff in perceived risk began, well before crack use began to increase in 1994. Thus, here again perceived risk was a leading indicator. Between 1991 and 1998 there was a considerable falloff in this belief in grades 8 and 10, as use rose quite steadily. Risk leveled in 2000 in grades 8 and 12 and a year later in grade 10. We think that the declines in perceived risk for crack and cocaine during the 1990s may well reflect an example of “generational forgetting,” wherein the class cohorts that were in adolescence when the adverse consequences were most obvious are replaced by newer cohorts who heard less about the dangers of the drug when they were growing up.

Disapproval

Disapproval of crack use was not included in the study until 1990, by which time it was at a very high level, with 92% of 12th graders saying that they disapproved of even trying it. Disapproval of crack use eased steadily in all three grades from 1991 through about 1997, before stabilizing.

Availability

Crack availability remained relatively stable across the interval for which data are available, as the fourth panel [in the crack use charts] illustrates. In 1987 some 41% of 12th graders said it would be fairly easy for them to get crack if they wanted some, and there has been little change since. Eighth and 10th graders, however, did report some modest increase in availability in the early 1990s, followed by a slow, steady decrease after 1995 in 8th grade and a sharper drop after 1999 in 10th.

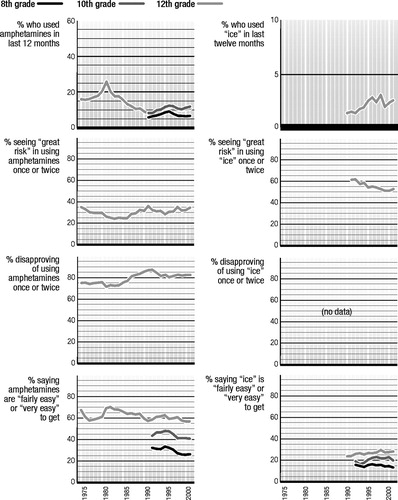

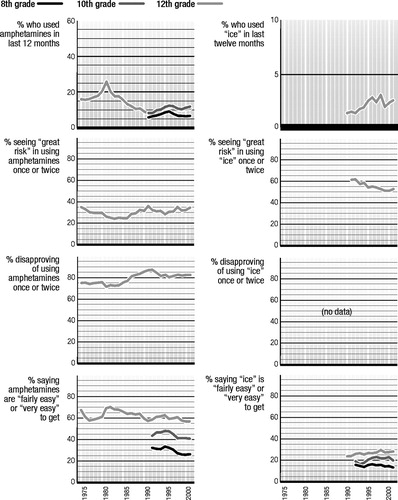

Amphetamines

Amphetamines, a class of psychotherapeutic stimulants, have had a relatively high prevalence of use in the youth population for many years. The behavior reported here is supposed to exclude any use under medical supervision. Amphetamines are controlled substances—they are not supposed to be bought or sold without a doctor’s prescription—but some are diverted from legitimate channels, and some are manufactured and/or imported illegally.

Trends in use

The use of amphetamines rose in the last half of the 1970s, reaching a peak in 1981—two years after marijuana use peaked. (Figure 7) We believe that the usage rate reached in 1981 (annual prevalence of 26%) may have been an exaggeration of true amphetamine use, because “look-alikes” were in common use at that time. After 1981 a long and steady decline in use by 12th graders began, and did not end until 1992.

As with many other illicit drugs, amphetamines made a comeback in the 1990s, with annual prevalence starting to rise by 1992 among 8th graders and by 1993 among the 10th and 12th graders. Use peaked in the lower two grades by 1996 and in 12th grade by 1997. Since those peak years, use declined by about a quarter in 8th grade, by less in 10th, and not at all in 12th. No further decline was seen in 2001.

Perceived risk

Only 12th graders are asked questions about the amount of risk they associate with amphetamine use or about their disapproval of that behavior. Overall, perceived risk has been less strongly correlated with usage levels (at the aggregate level) for this drug than for a number of others, although the expected inverse association pertained during much of the period 1975–2001. There was decrease in risk during the period 1975–1981 (when use was rising), some increase in risk in 1986–1991 (when use was falling), and some decline in perceived risk from 1991 to 1995 (in advance of use rising again). But in the interval 1981–1986, risk was quite stable even though use fell considerably. Since those are the years of peak cocaine use, it seems likely that some of the decline in amphetamine use in the 1980s was not due to a change in attitudes specific to that drug, but rather due to some displacement by another stimulant—cocaine.

Disapproval

Relatively high proportions of 12th graders have disapproved of even trying amphetamines throughout the life of the study (between 70% and 87%). Disapproval did not change in the late 1970s, despite the increase in use, though there seemed to be a one-year drop in 1981. From 1981 to 1992 disapproval rose gradually from 71% to 87% as use steadily declined. Disapproval then fell back about 6 or 7 percentage points in the next couple of years (as use rose), before stabilizing.

Availability

When the study started in 1975, amphetamines had a high level of reported availability. The level fell by about 10 percentage points by 1977, drifted up a bit through 1980, jumped sharply in 1981, and then began a long, gradual decline through 1991. There was a modest increase in availability at all three grade levels in the early 1990s, followed by some decline later, and stability after 1997.

Methamphetamine and ice

One subclass of amphetamines is called methamphetamine. This subclass (at one time called “speed”) has been around for a long time and gave rise to the phrase “speed kills” in the 1960s. Probably because of the reputation it got at that time as a particularly dangerous drug, it was not very popular for a long time. As a result, we did not even include a full set of questions about its use in the study’s questionnaires. One form of methamphetamine, crystal methamphetamine or “ice,” grew in popularity in the 1980s. It comes in crystallized form, as the name implies, and the chunks can be heated and the fumes inhaled, much like crack cocaine.

Trends in use

For most of the life of the study the only question about methamphetamine use has been contained in a single 12th grade questionnaire form. (Figure 8) Respondents who indicated using any type of amphetamines in the prior 12 months were asked in a sequel question to check on a pre-specified list which types they had used during that period. “Methamphetamine” was one type on the list, and data exist on its use since 1976. In 1976, annual prevalence was 1.9%; it then rose to 3.7% by 1981 (the peak year), before declining for a long period of time to 0.4% by 1992. It then rose again in the 1990s, reaching 1.3% by 1998, before declining to 0.9% in 1999 and then rising to 1.5% in 2001. In other words, it followed a cross-time trajectory very similar to that for amphetamines as a whole.

That questionnaire form also had “crystal meth” added in 1989 as another answer category that could be checked. It showed a level rate of use from 1989 to 1993 (at around 1.1%) followed by a period of increase to 2.5% by 1998 and then a decline to 1.9% in 2000. In 2001 it stood at 2.1%.

In 1990, in the 12th grade questionnaires only, we introduced our usual set of three questions, and 1.3% of 12th graders indicated any crystal methamphetamine (“ice”) use in the prior year, a figure which climbed to 3.0% by 1998, followed by a decline to 2.2% by 2000. It was 2.5% in 2001. (Note that these prevalence rates are quite close to those derived from the other question procedure, just described.)

Responding to the growing concern about methamphetamine use in general—not just crystal methamphetamine use—we added a full set of three questions about the use of any methamphetamine to the 1999 questionnaires for all three grade levels. These questions yield a somewhat higher annual prevalence for 12th graders: 4.3% in 2000, compared to the sum of the crystal meth and methamphetamine answers in the other question format, which totaled 2.8%. It would appear, then, that the long-term method we had been using for tracking methamphetamine use probably yielded an understatement of the absolute prevalence level, perhaps because some proportion of methamphetamine users did not correctly categorize themselves initially as amphetamine users (even though methamphetamine was given as one of the components of the amphetamines). We think it unlikely that the shape of the trend curve was distorted, however.

The newer questions show fairly high levels of methamphetamine use: annual prevalence rates in 2001 of 2.8%, 3.7%, and 3.9% for 8th, 10th, and 12th grades, respectively. Still, these levels are down some from 1999 in all three grade levels (not statistically significant).

Other measures

No questions have yet been added to the study on perceived risk, disapproval, or availability with regard to overall methamphetamine use. Data on two of these variables for crystal methamphetamine, specifically, may be found [in the charts on use of “ice”].

Heroin

Heroin is a derivative of opium. For many decades it has been taken primarily by means of injection into a vein. However, in the 1990s the purity of available heroin reached very high levels, making other modes of administration (like snorting and smoking) practical alternatives to injection. Therefore, in 1995, we introduced questions that asked separately about using heroin with and without a needle, so that we might see to what extent use without injection helped to explain the upsurge in use then occurring. The usage statistics presented [in the charts on heroin use] are based on heroin use by any method.

Trends in use

The annual prevalence of heroin use among 12th graders fell by half between 1975 and 1979, from 1.0% to 0.5%. (Figure 9) The rate then held amazingly steady for about 14 years. After about 1993, though, heroin use began to rise, and it rose substantially until 1996 (among 8th graders) or 1997 (among 10th and 12th graders). The prevalence rates roughly doubled at each grade level. Use then stabilized through 1999. In 2000 it declined significantly at 8th grade while rising significantly at 12th; but in 2001 annual prevalence declined significantly to 0.9% in both 10th and 12th grades.

The questions about use with and without a needle were not introduced until the 1995 survey, so they did not encompass much of the period of increasing use. Responses to these questions showed that by then about equal proportions of all users at 8th grade were using each of the two methods of ingestion, and some—nearly a third of the users—were using both ways. At 10th grade a somewhat higher proportion of all users took heroin by injection, and at 12th grade a higher proportion still. Much of the remaining increase in overall heroin use beyond 1995 occurred in the proportions using it without injecting, which we strongly suspect was true in the immediately preceding period of increase, as well. All of the decrease among 10th and 12th graders in 2001 was due to decreasing use without injecting.

Perceived risk

Students have long seen heroin to be one of the most dangerous drugs, which no doubt helps to account both for the consistently high level of personal disapproval of use (see next section) and the quite low prevalence of use. There have been some changes in perceived risk levels over the years, nevertheless. Between 1975 and 1986, perceived risk gradually declined, even though use dropped and then stabilized in that interval. There was then an upward shift in 1987 (the same year that perceived risk for cocaine jumped dramatically) to a new level, where it held for four years. In 1992 risk dropped to a lower plateau again, a year or two before use started to rise. Perceived risk then rose again in the latter half of the 1990s and use leveled off. Based on the short interval for which we have such data from 8th and 10th graders, it may be seen that perceived risk rose among them between 1995 and 1997, foretelling an end to the increase in use. Note that perceived risk has served as a leading indicator of use for this drug, as well as for a number of others.

Disapproval

There has been very little fluctuation in the very high disapproval levels for heroin use over the years, though what change there was in the last half of the 1990s was consistent with the concurrent changes in perceived risk and use.

Availability

The proportion of 12th grade students saying they could get heroin fairly easily, if they wanted some, remained around 20% through the mid-1980s; it then increased considerably from 1986 to 1992, before stabilizing at about 35%. At the lower grade levels, reported availability has been less, and has declined some since the mid-1990s.

Tranquilizers

Tranquilizers constitute another class of psychotherapeutic drugs that are legally sold only by prescription, like amphetamines. They are central nervous depressants and for the most part are comprised of benzodiazepines (minor tranquilizers, such as Valium). Respondents are told to exclude any medically prescribed use from their answers.

Trends in use

During the late 1970s and all of the 1980s, tranquilizers fell steadily from popularity, with use declining by three-quarters among 12th graders over the 15-year interval between 1977 and 1992. (Figure 10) Their use made a bit of a comeback during the 1990s, along with many other drugs. Annual prevalence more than doubled among 12th graders, rising steadily to 6.5% by 2001. (This rate compares to 10.8% in the peak year of 1977.) Use also has been rising steadily among 10th graders. Use peaked among 8th graders in 1996 and remains at about the same level in 2001.

Perceived risk

Data have not been collected on this variable, primarily due to questionnaire space limitations.

Disapproval

Data have not been collected on this variable, either.

Availability

As the number of 12th graders reporting non-medically prescribed tranquilizer use fell dramatically during the 1970s and 1980s, so did the proportion saying that tranquilizers would be fairly easy to get. Whether declining use caused the decline in availability, or vice versa, is unclear. Perceived availability fell from 72% in 1975 to 33% in 2001. Most of that decline occurred before the 1990s, though there was some further drop in the 1990s at all three grade levels, despite the fact that use rose some.

Barbiturates

Like tranquilizers, barbiturate sedatives are prescription-controlled psychotherapeutic drugs that are central nervous system depressants. They are used to assist sleep and relieve anxiety. Respondents are instructed to exclude from their answers any use that occurred under medical supervision. Usage data are reported only for 12th graders, because we believe that students in the lower grades tend to overreport use, perhaps including their use of nonprescription sleep aids or other over-the-counter drugs.

Trends in use

Like tranquilizers, the use of barbiturates by 12th graders fell in popularity rather steadily from the mid-1970s through the early 1990s. (Figure 11) From 1975 to 1992, use fell by three-fourths, from 10.7% annual prevalence to 2.8%. Usage rates showed some resurgence thereafter, reaching 6.2% by 2000, before finally leveling in 2001.

Another class of sedatives, methaqualone, has been included in the study from the beginning. In 1975 methaqualone use was about half the level of barbiturate use. Its use also declined steadily from 1981, when annual prevalence was 7.6%, through 1993, when annual prevalence reached the negligible level of 0.2%. Use increased some for a couple of years, reaching 1.1% in 1996, where it remained through 1999. Use then dropped to 0.8% in 2001.

Perceived risk

Trying barbiturates was never seen by most students as being very dangerous, and it is clear from the second facing panel that perceived risk cannot do much to explain the trends in use which occurred through 1986, at least. Perceived risk actually declined a bit between 1975 and 1986—an interval in which use also was declining. But then perceived risk shifted up some through 1991, consistent with the fact that use was still falling. It then dropped back some through 1995, as use was increasing.

Disapproval

Like many of the illicit drugs other than marijuana, barbiturates have received the disapproval of the great majority of all high school graduating classes over the past 25 years, though there have been some changes in level. Those changes have been consistent with the changes in actual use observed. Disapproval of using a barbiturate once or twice rose from 78% in 1975 to a high of 91% in 1990, where it held for two years. Then disapproval eroded a bit to 86% by 2000 during a period of increasing use. It remains there in 2001.

Availability

As the fourth facing panel shows, the availability of barbiturates has generally been declining during most of the life of the study, except for one shift up which occurred in 1981.

“Club drugs”—Ecstasy and rohypnol

There are a number of “club drugs,” so labeled because they are popular at night clubs and all-night dance parties called “raves.” This informal category includes LSD, MDMA (“ecstasy”), Rohypnol, methamphetamine, Ketamine (“special K”), and GHB. We will deal here primarily with ecstasy and Rohypnol. LSD and methamphetamine already have been discussed, and Ketamine and GHB were just added to the questionnaire in 2000.

The annual prevalence of GHB use in 2001 was 1.1%, 1.0%, and 1.6% in grades 8, 10, and 12. The annual prevalence of Ketamine use was 1.3%, 2.1%, and 2.5%. Both remained essentially unchanged in 2001 from their levels in 2000—the first year in which they were measured.

Rohypnol and GHB have been labeled “date rape drugs” because both can induce amnesia of events that occurred while under the influence of the drug and have been used in connection with rapes or seductions. Use is likely underreported since the user may be unaware of having used the drugs.

Questions about the use of Rohypnol were added to the survey in 1996. They revealed low levels of use that the respondent was able to report—around 1% in all three grade levels. At 8th grade, use began falling immediately after 1996 and by 1999 had fallen by half. In the upper two grades, use first rose for a year or two before beginning to fall back to its original level by 1999. There has been rather little net change in use since 1999.

Limitations on questionnaire space precluded asking about perceived risk, disapproval, or availability.

Ecstasy

Trends in use

Ecstasy is actually a form of methamphetamine but is used more for its mildly hallucinogenic properties. (Figure 12) Questions about the use of MDMA, or ecstasy, were added to the surveys of secondary school students in 1996. (We have had questions on this drug since 1991 in the questionnaires answered by college students and young adults. Their results showed ecstasy use beginning to rise above trace levels in 1995, and continuing to rise at least through 2000.) Annual prevalence in 10th and 12th grades in 1996 was 4.6%—actually considerably higher than among college students and young adults at that point—but fell in both grades over the next two years. Use then rose sharply in both grades in 1999 and 2000, bringing annual prevalence up to 5.4% among 10th graders and 8.2% among 12th graders. In 2000 use also began to rise among 8th graders, to 3.1%. In 2001, use increased again in all three grades, but by less than in the two previous years. In other words, the increase was slowing. [The 2000–2001 increases in use were not statistically significant for individual grades, but were significant across the three grades combined. Thirty-day prevalence showed a less consistent pattern of change this year, possibly reflecting a very recent turnaround in use in 12th grade; but another year of data is needed to clarify this.]

Perceived risk and disapproval

The charts on [use of MDMA] show little change in perceived risk of ecstasy until 2001, when it jumped by 8 percentage points; this sharp rise likely explains the deceleration of the increase in use. Disapproval of ecstasy use has declined slightly since 1998.

Availability

The charts also show a dramatic rise in perceived availability since 1991—particularly in the years 2000 and 2001. Special analyses show that this drug is still diffusing to communities that have not had it before, possibly explaining why use rose in 2001 despite the sharp increase in perceived risk. The increase in ecstasy use in 1999 occurred primarily in the Northeast and in large cities, whereas in 2000 the increase diffused into all of the other regions.

Alcohol

Alcoholic beverages—which include beer, wine, wine coolers, and hard liquor—have been among the most widely used substances by American young people for a very long time. In 2001 the proportions of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders who admitted drinking an alcoholic beverage in the 30- day period prior to the survey were 22%, 39%, and 50%, respectively. There are quite a number of usage measures of relevance for alcohol, all of which are contained in the tables at the end of [the original] report. Here we will focus on the pattern of alcohol consumption that probably is of the greatest public health concern—episodic heavy drinking, or what we have called “binge drinking” for short. It is measured in this study by the reported number of occasions on which the respondent had five or more drinks in a row during the prior two-week interval. We present the prevalence of such binge drinking behavior in the first panel.

Trends in use

Judging by the data from 12th graders, binge drinking reached its peak at about the time that overall illicit drug use did, in 1979. (Figure 13) It held steady for a couple of years and then declined substantially from 41% in 1983 to a low of 28% in 1992 (also the low point of any illicit drug use). This was an important improvement—a drop of almost one-third in binge drinking. Although illicit drug use rose considerably in the 1990s in proportional terms, binge drinking rose by only a small fraction—about 4 percentage points among the 12th graders—between 1992 and 1998. There was some upward drift between 1991 (13%) and 1996 (16%) among 8th graders, and between 1992 (21%) and 1997 (25%) among 10th graders. In the years since those recent peaks, there has been a slight decline in use in all three grades, but the changes have been very modest.

One point to note in these findings is that there is no evidence of any “displacement effect” in the aggregate between alcohol and marijuana—a hypothesis frequently heard. The two drugs have moved much more in parallel over the years than in opposite directions.

Perceived risk

While for most of the study the majority of 12th graders have not viewed binge drinking on weekends as carrying a great risk (see panel two), there was in fact a fair-sized increase in this measure between 1982, when it was 36%, and 1992, when it reached 49%. There then followed a modest decline to 43% by 1997, before it stabilized. These changes track fairly well the changes in actual binge drinking. We believe that the public service advertising campaigns in the 1980s against drunk driving, in general, as well as those that urged use of designated drivers when drinking, may have contributed to the increase in perceived risk of binge drinking. As we have published elsewhere, drunk driving by 12th graders declined during that period by an even larger proportion than did binge drinking.

Disapproval

Disapproval of weekend binge drinking moved fairly parallel with perceived risk, suggesting that increasingly such drinking (and very likely the drunk-driving behavior often associated with it) became unacceptable in the peer group. Note that the rates of disapproval and perceived risk for binge drinking are higher in the lower grades than in 12th grade. Both variables showed some erosion at all grade levels in the early 1990s.

Availability

Perceived availability of alcohol, which until 1999 was asked only of 8th and 10th graders, has been very high and mostly steady in the 1990s, although there has been some decline in 8th grade since 1996.

Cigarettes

Cigarette smoking has been called the greatest preventable cause of disease and mortality in the United States. At current rates of smoking, this statement surely remains true for these newer cohorts of young people.

Trends in use

We know that differences in smoking rates between different birth cohorts (or, in this case, high school class cohorts) tend to stay with those cohorts throughout the life cycle. (Figure 14) This means that it is critical to prevent smoking very early. It also means that the trends in a given historical period may differ across different grade levels.

Among 12th graders, 30-day prevalence of smoking reached a peak in 1976, at 39%. (The peak likely occurred considerably earlier for lower grade levels, as these same class cohorts passed through them in previous years.) There was about a one-quarter drop in 30-day prevalence between 1976 and 1981, when the rate reached 29%, a level at which it remained for more than a decade, until 1992 (28%).

In the 1990s, smoking began to rise sharply, starting in 1992 among 8th and 10th graders, and in 1993 among 12th graders. Over the next four to five years smoking rates increased by about one-half in the lower two grades and by almost one-third in grade 12—very substantial increases. Smoking peaked in 1996 for 8th and 10th graders and in 1997 for 12th graders, before beginning a decline that continued into 2001. Since those peak levels in the mid-1990s, the 30-day prevalence of smoking has declined by 42% in 8th grade, 30% in 10th, and 19% in 12th. (In 2000 a single question was introduced to measure the annual prevalence of “bidis,” a type of flavored cigarette imported from India. The 2001 annual rates for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders were 2.7%, 4.9%, and 7.0%. For the 8th and 10th grades this represented a significant decline in use.)

Perceived risk

Among 12th graders, the proportion seeing great risk in pack-a-day smoking rose before and during some of the time that use first declined. It leveled in 1980 (before use leveled), declined a bit in 1982, but then started to rise again gradually for five years. (It is possible that cigarette advertising effectively offset the effects of rising perceptions of risk during that five-year period.) Perceived risk fell some in the early 1990s at all three grade levels as use increased sharply; but after 1995 perceived risk began to climb in all three grades (coincident with use starting to decline in grades 8 and 10, but a year before it started to decline in 12th grade). Note the considerable disparity of the levels of perceived risk among grade levels. For some years, only around 50% of 8th graders saw great risk in pack-a-day smoking.

Disapproval

Disapproval rates for smoking have been fairly high throughout the study and, unlike perceived risk, are higher in the lower grade levels. Among 12th graders there was a gradual increase in disapproval of smoking from 1976 to 1986, a slight erosion over the following five years, then a steeper erosion from the early 1990s through 1997. Since 1997, disapproval has been increasing among 12th graders. In the two lower grades a decline in disapproval occurred between 1991 and 1996, the period of sharply increasing use. Since those low points, there has been a steady increase in disapproval. A number of other attitudes related to smoking have been becoming more negative, as well.

Availability

Availability of cigarettes is reported as very high by 8th and 10th graders. (We do not ask the question of 12th graders, for whom we assume accessibility is nearly universal.) Since 1996 availability has been declining, particularly among the 8th graders.

Smokeless tobacco

Smokeless tobacco comes in two forms: “snuff” and “chew.” Snuff is finely ground tobacco usually sold in tins, either loose or in packets. It is held in the mouth between the lip or cheek and gums. Chew is a leafy form of tobacco, usually sold in pouches. It too is held in the mouth and may, as the name suggests, be chewed. In both cases, nicotine is absorbed by the mucous membranes of the mouth. Because smokeless tobacco stimulates saliva production, it is sometimes referred to as “spit” tobacco.

Trends in use

The use of smokeless tobacco by teens has been decreasing gradually from recent peak levels in the mid-1990s, and the overall declines have been substantial. (Figure 15) Among 8th graders 30-day prevalence is down from a 1994 peak of 7.7% to 4.0% in 2001; 10th graders’ use is down from a 1994 peak of 10.5% to 6.9% in 2001; and 12th graders’ use is down from a 1995 peak of 12.2% to 7.8% in 2001. These reflect relative declines from peak levels of 48%, 34%, and 36%, respectively. One could say, more generally, that teen use of smokeless tobacco is down by about 40% from the peak levels reached in the mid-1990s.

Thirty-day prevalence of daily use of smokeless tobacco also has fallen gradually, but appreciably, in recent years. The daily usage rates in 2001 are 1.2%, 2.2%, and 2.8% in grades 8, 10, and 12. These are down by between a quarter and a half from the peak levels recorded in the early 1990s, with the greatest proportional decline in 8th grade and the least in 12th.

It should be noted that smokeless tobacco use among American young people is almost exclusively a male behavior. For example, among males the 30-day prevalence rates in 2001 are 6.9%, 12.7%, and 14.2% in grades 8, 10, and 12, respectively, versus 1.4%, 1.6%, and 1.6% among females. The respective current daily use rates for males are 2.5%, 4.5%, and 5.6% compared to 0.1%, 0.3%, and 0.3% for females. There are some other important demographic differences as well. Use tends to be much higher in the South and North Central regions of the country than in the Northeast and West. It also tends to be more concentrated in non-metropolitan areas than metropolitan ones and to be negatively correlated with the education level of the parents. Use also tends to be much higher among Whites than among African Americans or Hispanics.

Perceived risk

The recent low point in the level of perceived risk for smokeless tobacco was 1995 in all three grades. Since 1995 there has been a gradual but substantial increase in proportions saying there is a great risk in using it regularly—among 8th graders, from 34% to 38% in 2001; and among 10th graders, from 38% to 46%. Among 12th graders, perceived risk went from 33% in 1995 to 45% in 2001. It thus appears that one important reason for the appreciable declines in smokeless tobacco use during the latter half of the 1990s was the fact that an increasing proportion of young people were persuaded of the dangers of using it.

Disapproval

Only 8th and 10th graders are asked about their personal disapproval of using smokeless tobacco regularly. The recent low points for disapproval in both grades were 1995 and 1996. Since 1996, disapproval has risen from 74% to 79% among 8th graders and from 71% to 76% among 10th graders.

Availability

There are no questions in the study concerning the perceived availability of smokeless tobacco.

Steroids

Unlike all of the other drugs discussed in this volume, anabolic steroids are not usually taken for their psychoactive effects, but rather for their physical effects on the body, in particular for their effects on muscle and strength development. They are similar to the other drugs studied here, though, in that they are controlled substances for which there is an illicit market and which can have adverse consequences for the user. Questions about their use were added to the study beginning in 1989. Respondents are asked: “Steroids, or anabolic steroids, are sometimes prescribed by doctors to promote healing from certain types of injuries. Some athletes, and others, have used them to try to increase muscle development. On how many occasions (if any) have you taken steroids on your own—that is, without a doctor telling you to take them?”

Trends in use

Steroids are used predominately by males; therefore, data based on all respondents can mask the higher rates and larger fluctuations that occur among males. (Figure 16) For example, in 2001 the annual prevalence rates were two to four times as high among males as among females. Boys’ annual prevalence rates were 2.3%, 3.3%, and 3.8% in grades 8, 10, and 12, compared with 1.0%, 1.0%, and 1.1% for girls. Between 1991 and 1997 the overall annual prevalence rate was quite stable in 8th grade, ranging between 0.9% and 1.2%; and in 10th grade it was similarly stable, ranging between 1.0% and 1.2%. (See the first panel [of the charts on steroid use].) In 1999, however, use jumped from 1.2% to 1.7% in 8th and 10th grades. Almost all of that increase occurred among boys (increasing from 1.6% to 2.5% in 8th grade and from 1.9% to 2.8% in 10th). In other words, the rates among boys increased by about 50% in a single year. In 12th grade there was a different trend story. With data going back to 1989, we can see that steroid use first fell from 1.9% overall in 1989 to 1.1% in 1992—the low point. From 1992 to 1999 there was a more gradual increase in use, reaching 1.7% in 2000. In 2001 use rose significantly among 12th graders, quite possibly reflecting the effect of the younger, heavier-using cohorts getting older.

Perceived risk

Perceived risk and disapproval were asked of 8th and 10th graders only for a few years, before the space was allocated to other questions. All grades seemed to have a peak in perceived risk around 1993. The longer-term data from 12th graders, however, show a 6 percentage-point drop between 1998 and 1999, and another 4 percentage-point drop in 2000. This sharp a change is quite unusual and highly significant, suggesting that some particular event (or events) in 1998 changed beliefs about the dangers of steroids. (It seems likely that there was at least as large a drop in the lower grades, as well, where the sharp upturn in use occurred that year.)

Disapproval

Disapproval of steroid use has been quite high for some years. (Along with the high levels of perceived risk, disapproval rates no doubt help to explain the low absolute prevalence rates.) By 2000 there was only slight falloff in disapproval, despite the decline in perceived risk, but in 2001 there was a significant decrease in disapproval as well.

Availability

Perceived availability is quite high for steroids and considerably higher at the upper grades than in the lower ones. However, it should be noted that some over-the-counter substances, like androstenedione, are legally available to all age groups and are sold in health food stores, drugstores, and even supermarkets.

Subgroup differences

Space does not permit a full discussion or the documentation of the many subgroup differences on the host of drugs covered in this report. However, the much longer versions of Volume I in this same series—both the one published in 2001 and the one forthcoming in 2002—contain an extensive appendix with tables giving the subgroup prevalence levels and trends for all of the classes of drugs discussed here. Chapters 4 and 5 in those volumes also present a more in-depth discussion and interpretation of those differences. Comparisons are made by gender, college plans, region of the country, community size, socioeconomic level (as measured by the educational level of the parents), and race/ethnicity. Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper 53, available on the study’s Web site (www.monitoringthefuture.org), provides in graphic form the many subgroup trends for all drugs.

Gender

Generally, we have found males to have somewhat higher rates of illicit drug use than do females (particularly higher rates of frequent use), much higher rates of smokeless tobacco and steroid use, higher rates of heavy drinking, and roughly equivalent rates of cigarette smoking (though among 12th graders the two genders have reversed order twice during the life of the study). These gender differences appear to emerge as students grow older. Usage rates for the various substances tend to move much in parallel across time for both genders, although the absolute differences tend to be largest in the higher prevalence periods.

College plans

Those students who are not college-bound (a decreasing proportion of the total youth population) are considerably more likely to be at risk for using illicit drugs, for drinking heavily, and particularly for cigarette smoking while in high school than are the college-bound. Again, these differences are largest in periods of highest prevalence. In the lower grades, the college-bound showed a greater increase in cigarette smoking in the early to mid-1990s than did their non-college-bound peers.

Region of the country

The differences associated with region of the country are sufficiently varied and complex that we cannot do justice to them here. In general, though, the Northeast and the West have tended to have the highest proportions of students using any illicit drug, and the South the lowest (though these rankings do not apply to many of the specific drugs). In particular, the cocaine epidemic of the early 1980s was much more pronounced in the West and the Northeast than in the other two regions, though the differences decreased as the overall epidemic subsided. While the South and the West once had lower rates of drinking among students than the other two regions had, those differences have narrowed some in recent years. Cigarette smoking rates have consistently been lowest in the West. The upsurge of ecstasy use in 1999 occurred primarily in the Northeast, but that drug’s newfound popularity spread to the three other regions of the country in 2000, while stabilizing in the Northeast.

Population density

There have not been very large or consistent differences in overall illicit drug use associated with population density over the life of the study, helping to demonstrate just how ubiquitous the illicit drug phenomenon has been in this country. In the last few years, the use of a number of drugs has declined more in the urban areas than in the non-urban ones, leaving the non-urban areas with higher rates of use. The upsurge in ecstasy use in 1999 was largely concentrated in urban areas, but in 2001 there are only modest differences in ecstasy use as a function of population density. Crack and heroin use are not concentrated in urban areas, as is commonly believed, meaning that no parents should assume that their youngsters are immune to these threats simply because they do not live in a city.

Socioeconomic level

For many drugs the differences in use by socioeconomic class are very small, and the trends have been highly parallel. One very interesting difference occurred for cocaine, which was positively associated with socioeconomic level in the early 1980s. That association had nearly disappeared by 1986, however, with the advent of crack, which offered cocaine at a lower price. Cigarette smoking showed a similar narrowing of class differences, but this time it was a large negative association with socioeconomic level that diminished considerably, between roughly 1985 and 1993. In more recent years that negative association is re-emerging in the lower grades, as use declines faster among students from more educated families. Rates of binge drinking are roughly equivalent across the classes in the upper grades, and have been for some time among 12th graders.

Race/ethnicity