Psychotherapy Update for the Practicing Psychiatrist: Promoting Evidence-Based Practice

Abstract

The last three decades have witnessed significant advances in psychotherapy. Numerous scholarly articles and books have been devoted to pertinent topics in the field, making it difficult for the practicing clinician to keep up with this rapidly growing area. The purpose of this article is to provide some guidelines on how to evaluate the empirical literature in psychotherapy and then to explore three key areas: evidence-based psychotherapies for patients with psychiatric disorders, individual variables that predict differential outcome to treatment, and the therapeutic alliance. Finally, two case examples will be presented to illustrate how knowledge of the empirical literature can facilitate an evidence-based approach to the daily practice of psychotherapy in general psychiatry.

The early 1990s witnessed a significant paradigm shift in the practice of clinical medicine and medical education, with greater emphasis given to the individual scientist practitioner's critical appraisal skills and his or her ability to deliver “evidence-based” treatments. For the practicing psychiatrist this poses significant challenges as it requires maintaining a connection with advances in pharmacological and psychological treatments. For many psychiatrists keeping up with the former is much easier than the latter, given the availability of psychiatry online resources, courses, and conferences dedicated to this area. Remaining abreast of developments in psychotherapy seems to be more challenging, perhaps because of the narrow exposure to psychotherapy during training, greater emphasis on pharmacology, and unfamiliarity with resources dedicated to this area, the majority of which are located outside the discipline of psychiatry.

The purpose of this article is to assist the practicing clinician with the difficult task of keeping up with the empirical psychotherapy literature. First and foremost a discussion on how to evaluate the extensive research in this area will be presented with an emphasis on meta-analyses. Second, a brief review of the empirical psychotherapy literature will be presented with a focus on evidence-based psychotherapies for patients with psychiatric disorders. Third, individual variables that predict differential outcomes to treatment will also be discussed as this is an emerging area of research. Fourth, the therapeutic alliance will be briefly discussed as it has remained a robust variable in psychotherapy outcome. Finally, two case examples will be presented to help illustrate how knowledge of the empirical literature can guide evidence-based practice.

EVALUATING RESEARCH

The gold standard in evidence-based medicine is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). In the RCT one treatment is compared with a placebo or a waiting list or an active comparison is performed under well-controlled conditions. In psychotherapy research this involves the use of well-defined treatment manuals that operationalize specific psychotherapies and reliable and valid instruments that assess therapist adherence, therapist competence, treatment process (i.e., therapeutic alliance), and treatment outcome (i.e., depression) variables.

There is an extensive body of literature examining RCTs for many types of psychotherapies, making it challenging for the practicing psychiatrist to remain current with the field. Reading reviews that provide guidelines can be an efficient method of keeping in touch with the literature. Two types of reviews are available: narrative reviews or systematic reviews. Although narrative reviews are helpful in providing an introduction to the area, systematic reviews or meta-analyses are more rigorous in that they use explicit search strategies, have clear standards for the studies they include, and arrive at an “effect size” that provides a quantitative analysis of how beneficial a treatment is compared with no treatment or an alternate treatment. Effect sizes (ES) are described as small (0.20–0.49), moderate (0.50–0.79), or large (0.80 and larger). The larger the effect size is, the greater the indication that a specific treatment is effective. The excellent article by Lam and Kennedy (1) included in this issue describes meta-analyses in detail so that treatment decisions can be made and follow an evidence-based approach.

Although the notion of levels of evidence has been discussed for some time (2), Lam and Kennedy provide an easy-to-follow step-by-step approach so that one is able to appraise a meta-analysis. Rigorous meta-analyses and RCTs carried out in several sites provide the highest level of evidence (level 1) for a particular treatment (1). Meta-analyses have been criticized for including poorly carried out RCTs and heterogeneous samples and for being subject to interpreter bias (3). However, more recent meta-analyses, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, have taken many of these criticisms into account.

EVIDENCE-BASED THERAPIES FOR PATIENTS WITH PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

It is not the purpose of this article to present an exhaustive review of the psychotherapy outcome literature but rather to present a focused review that examines the most recent research. Several narrative reviews that appraise the empirical psychotherapy outcome literature are available (4). For the purpose of this article, PsycINFO and PubMed were searched using the MESH terms “meta-analyses,” “meta-analysis,” and “review” for the most common psychiatric disorders treated by psychiatrists (i.e., depression, anxiety disorders, and others), and the specific psychotherapies that have recently been associated with successful outcomes with these disorders (i.e., cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and so on). Only the most recent meta-analyses conducted over the past decade (2000–2009) were included as these reviews adhere to more rigorous standards, and earlier studies have been systematically reviewed elsewhere (5). In total, 67 meta-analyses were found for a variety of psychotherapies across the major psychiatric disorders. Duplicates of meta-analyses by the same author reported in several journals were not included, but rather the most recent one was selected for discussion. All meta-analytic reviews referred to in this article reviewed studies that made comparisons between various control groups such as waiting lists, no treatment groups, and other active forms of treatments. In addition, RCTs that support the use of new emerging therapies (e.g., mindfulness-based cognitive therapy), are also discussed as some of these therapies hold promise for the future if level 1 evidence can be established. Some of these therapies are discussed at length in separate articles in this issue of Focus.

Tables 1 through 6 list the meta-analyses for the common psychiatric disorders for which psychotherapies have been investigated. Each table lists the specific disorder studied, the author(s), search years, number of studies included in the meta-analyses and subjects included if this information is given, and the results reported in effect sizes : either the exact figures or described as small, moderate, or large or percentage improved. If information was missing, authors were contacted by E-mail to provide it, but not all responded. Acronyms are used in the tables, and these are explained in a footnote to the table.

Several meta-analyses have been performed for unipolar depression and other mood-related disorders. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Study set the gold standard for psychotherapy research in the late 1980s (6). Results revealed positive outcomes for medications (imipramine), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and case management for mild to moderate depression, and superior effects for medication in severe depression and for IPT in the nonfunctionally impaired severely depressed patient. Since the publication of this well-known study, numerous RCTs and several meta-analyses have continued to show positive results for several psychotherapies in the treatment of depression. In the past decade alone, at least 24 meta-analyses demonstrated moderate to large effect sizes for many psychotherapies for depression.

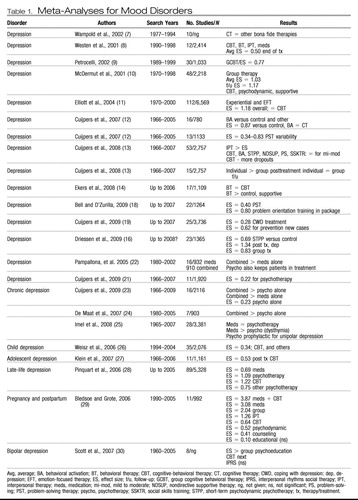

Table 1 shows a range of effect sizes for a variety of psychotherapies for the treatment of depression with large effect sizes noted for CBT whether delivered in individual or group formats (7–14). CBT is an integrated therapy in that it incorporates both cognitive and behavioral components in the conceptualization of patient problems and in the delivery of treatment. The fundamental premise of CBT is that psychological distress, whether it is manifested in mood, anxiety, or other problematic symptoms, is a result of specific maladaptive thought processes, which in turn lead to difficulties in emotions and behavior. Treatment includes challenging these distortions in the context of a collaborative relationship and a positive therapeutic alliance. Self-monitoring and behavioral techniques that incorporate specific homework exercises expose the patient to alternate interpretations of events and help change behavior in a positive direction. Helping patients to increase positive events in depression and decrease avoidance in anxiety (i.e., exposure) reduces maladaptive symptoms.

|

Table 1. Meta-Analyses for Mood Disorders

Large effect sizes have also been reported for IPT especially for patients with certain psychosocial stressors and “obsessional” personality traits (15). IPT is a brief, structured, integrative therapy originally developed for patients with depression. The fundamental assumption in IPT, is that the onset of, maintenance of, and recovery from depression is determined by four key interpersonal events: losses, role transitions, interpersonal conflicts, and interpersonal deficit. Therapy focuses on integrating a medical model of depression as well as understanding and working through these key interpersonal areas.

Newer therapies such as behavioral activation and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) also demonstrate large effect sizes (11–12, 14). Behavioral activation is based on behavior theory and involves activity scheduling and the introduction of positive reinforcing events. Behavioral activation can be integrated with medications and other psychotherapies and is an easy-to-administer treatment requiring much less therapist training than the other psychotherapies. However, given the demand for participation in activities, patient compliance is crucial. EFT is an experiential therapy that integrates client-centered and gestalt techniques and is extensively described in a separate article in this issue. This therapy has been studied in RCTS as well as in a meta-analysis (11) and has been found to be helpful in the treatment of depression, with improvements in self-esteem and interpersonal problems noted in the long term.

A recent meta-analysis also showed moderate to large effect sizes for short-term psychodynamic therapy (STPP), better known as brief psychodynamic therapy, which incorporates the active ingredients of change of long-term psychodynamic therapy but in a briefer format. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy involves a heterogeneous group of treatments that focus on transference, defenses, or other intrapsychic conflicts. Interventions in STPP can focus on either supportive or expressive dimensions, with evidence supporting both as active ingredients of change in the outcome of treatment (13, 16).

Problem-solving therapy and the coping with depression (CWD) psychoeducation package have also been investigated in the treatment of depression. Both therapies are brief and active and engage the patient in working through difficulties in a systematic manner to learn specific skills that can be used when dealing with depressive symptoms. Both treatments show small effect sizes as a treatment for depression, although CWD appears to be effective as a preventative measure for future episodes (13, 17–19). However, a component analysis has revealed that the problem orientation package of problem-solving therapy has a much higher effect size than the complete package, raising issues as to which ingredients act as mechanisms of change in this form of treatment.

Of significance is a recent comparative meta-analysis by Cuijpers et al. (13), who found that although CBT, IPT, behavioral activation, short-term psychodynamic therapy, nondirective supportive therapy, problem-solving therapy, and social skills training were all effective for mild to moderate depression, IPT had a slight advantage and problem-solving therapy showed the fewest dropouts. Cuijpers et al. (20) also found that individual treatment produced better outcomes than group treatment at the end of treatment, but no significant difference was noted at follow-up. In a recent article in which highly stringent criteria were applied to the selection of studies, resulting in only 11 RCTs, a lower effect size was found for psychotherapies for the treatment of depression (21). Although this result requires replication, it is important to note that the use of highly stringent criteria excludes many well performed RCTs that have clearly established effectiveness.

The above meta-analyses have focused primarily on unipolar mild to moderate depression and have essentially established what was concluded in the early NIMH trials: most psychotherapies seem to be generally effective in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Three meta-analyses have looked at chronic severe depression or dysthymia and have generally all found the same results: combined treatments that include medication and psychotherapy fare better than psychotherapy or medication delivered alone (22, 23, 25). This result probably comes as no surprise to the clinician who finds that these patients are more resistant to medications as well as to psychotherapy, thereby requiring an integration of both treatments. An additional meta-analysis showed superior outcomes with combined treatment than with medication alone, and patients remained in treatment longer if psychotherapy was integrated into the treatment plan (24).

Meta-analyses have also been conducted for childhood and adolescent depression, late-life depression, pregnancy and postpartum depression, and bipolar depression. In childhood depression effect sizes have been small at best, but recent studies showed moderate effect sizes in adolescent depression with greater than half of patients improving with CBT (26, 27). In the late-life period CBT and other “psychotherapies” grouped together showed high effect sizes (28). These psychotherapies included supportive, psychodynamic, and other treatments. Bledsoe and Grote (29) conducted a meta-analysis comparing several psychotherapies in the pregnancy and postpartum period and found large effect sizes for medication plus CBT, group therapy, and IPT, with moderate effect sizes for CBT and psychodynamic therapy, and small effect sizes for counseling and psychoeducation. The poorest results were found for bipolar depression for which large effect sizes have been found for psychoeducation and moderate effect sizes for CBT for enhancing medication compliance. Nonsignificant results have been found for interpersonal social rhythms therapy, a form of IPT (30).

Although many therapies have been found to be effective for depression post-treatment, many patients continue to have residual symptoms and tend to relapse. Therefore, neither psychotherapy nor medication provides a cure, but both treatments can be integrated in an evidence-based, patient-directed manner to provide the best outcome. Several psychotherapies such as CBT and IPT have focused on relapse prevention by increasing sessions, providing “booster” sessions, and focusing on prevention techniques. Because of the limitations of traditional cognitive therapy, new variants of CBT have emerged over the last two decades. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has recently been investigated for those patients with three or more episodes of depression and shows promise in four recent clinical trials (31). Mindfulness is not a specific form of therapy but an ancient Buddhist meditative technique. When practiced frequently, mindfulness produces a state of nonreactivity and detachment from disturbing thoughts and feelings that lead to depression, anxiety, and emotional dysregulation. There are many exercises that are considered “mindfulness” based. Some of these involve paying attention to the breath, attending to the moment, or focusing on an object. Mindfulness is an intriguing approach not only for chronic depression but also for other psychiatric disorders and its application in psychiatry is discussed in detail in a separate article in this issue.

Unlike for depression, there are few comparative trials of psychotherapy in the treatment of anxiety disorders. The majority of studies have compared medications, CBT, components of CBT (e.g., exposure, exposure and response prevention, and behavior therapy), relaxation, and eye movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR) with wait list controls. There is heavy emphasis on the behavioral component of CBT in the treatment of anxiety disorders as patients are encouraged to “expose” themselves to the feared situation and not engage in avoidance. In EMDR patients are asked to recall a traumatic memory, and lateral sets of eye movements are induced by the therapist who moves his or her finger across the patient's field of vision. The patient is then asked to report any feelings, thoughts, or images that arise, which then become the focus of the next set of eye movements. This process continues until the distress evoked by the memory diminishes.

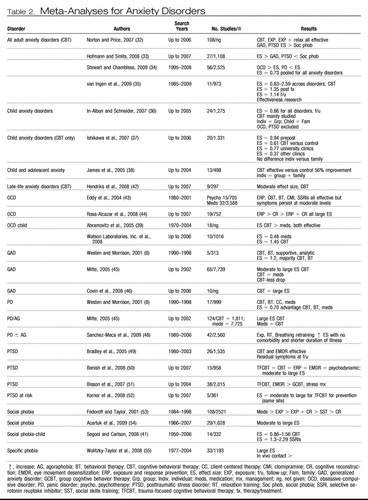

Table 2 shows 27 meta-analyses over the past decade for all anxiety disorders across the lifespan. When all anxiety disorders are combined, moderate to large effect sizes are evident for the treatment of all adult anxiety disorders with some studies showing large effect sizes for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and lower effect sizes for social phobia (32–35).

|

Table 2. Meta-Analyses for Anxiety Disorders

Large effect sizes have also been found for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders with CBT, with individual treatments equaling family treatment or group treatments, university clinics producing moderate effect sizes, and community clinics showing small effect sizes (36–38). These findings could indicate that CBT performed in the “real-world” community clinic is less effective, possibly due to several factors such as severity of illness, decreased therapist competency, or decreased therapist adherence to CBT interventions and poor patient compliance with treatment. Separate meta-analyses have been conducted for childhood OCD and social phobia, again showing large effect sizes with CBT treatments (39–41). Moderate effect sizes have also been found for CBT for late-life anxiety disorders (42).

With respect to specific adult anxiety disorders two recent meta-analyses showed very large effect sizes for exposure and response prevention and medications for OCD; however, symptoms do persist at moderate levels after treatment (43, 44). The treatment of GAD with CBT, behavior therapy, or medications also demonstrates high effect sizes, with small to moderate effect sizes for supportive and psychodynamic treatments (8, 45, 46). Moderate to large effect sizes have also been found for CBT and medications in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, but this effect seems to decrease with increasing comorbidity and longer duration of illness (8, 47, 48). Trauma-focused CBT and EMDR seem to have larger effect sizes as indicated in more recent meta-analyses, although controversy regarding EMDR as a treatment for PTSD still exists (49–52).

In social phobia moderate to large effect sizes have been found for both CBT and medications (53, 54). In addition, dismantling studies have shown that exposure alone is superior to exposure combined with cognitive reconstruction and social skills training (53). The treatment of specific phobias with in vivo exposure interventions also indicates large effect sizes (55). Therefore, at the present time CBT remains the mainstay of treatment for patients with anxiety disorders with moderate to large effect sizes demonstrated for different anxiety disorders across the lifespan. However, residual symptoms are prominent with increasing symptom severity and comorbidity, once again suggesting longer treatment and possibly combined treatment with medication for optimal response in the long term (49)

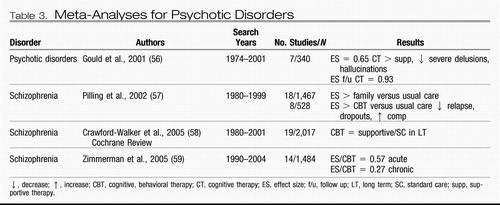

CBT has recently been investigated for psychotic disorders with two meta-analyses showing moderate to large effect sizes for decreasing patient distress associated with psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions (Table 3 Gould et al.) (56) found a moderate effect size in decreasing distress associated with psychotic symptoms after treatment with CBT compared with supportive therapy. However, a much larger effect size was found for CBT at follow-up. Pilling et al. (57) also found large effect sizes for CBT compared with usual care in decreasing relapse and dropouts, and increasing medication and treatment compliance in patients with schizophrenia. Zimmerman et al. (59) found a moderate effect size for CBT for acute psychotic symptoms and a small effect size for chronic psychosis. However, a recent Cochrane review did not find any difference between CBT and supportive therapy in the long term, indicating that more work may be needed in this area (58).

|

Table 3. Meta-Analyses for Psychotic Disorders

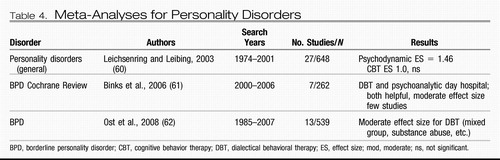

Few meta-analyses have been conducted for personality disorders, given the limited research in this area, with the exception of borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Table 4). Leichsenring and Leibing (60) found large effect sizes for both psychodynamic therapy and CBT for the treatment of a variety of personality disorders. Two meta-analyses were conducted for BPD with comparisons being made between dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and psychoanalytic day hospital treatment. DBT is an integrated treatment that incorporates techniques from CBT and mindfulness to promote emotion regulation and to decrease impulsivity leading to self-injurious behavior. Binks et al. (61) found moderate effect sizes for both DBT and psychodynamic therapy with only a few studies in their analyses. Psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization treatment was found to be helpful in patients with BPD, with an advantage noted over DBT in decreasing parasuicidal behavior and hospital admissions (61). A more recent meta-analysis found a moderate effect size for DBT; however, the sample consisted of patients from mixed diagnostic groups (i.e., substance abuse and others) (62).

|

Table 4. Meta-Analyses for Personality Disorders

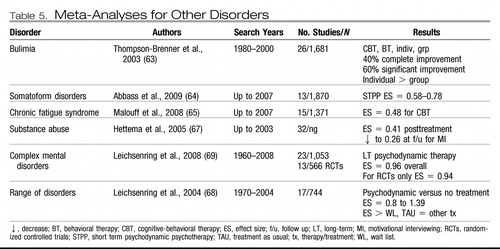

Meta-analyses have also been reported for other psychiatric conditions (Table 5). Moderate effect sizes have been reported for CBT and behavior therapy with individual and group treatment of bulimia (63). Abbass et al. (64) found a moderate effect size for short-term psychodynamic therapy for the treatment of somatoform disorders, whereas Malouff et al. (65) found a small to moderate effect size for treating chronic pain with CBT, which has been reported in other studies (66). Moderate to large effect sizes have also been reported for motivational interviewing (MI) for patients with substance abuse, although these effects seem to decrease over time (67), suggesting the need for “booster sessions,” which are essential in many chronic conditions. MI is a specific interviewing technique with the aim of assessing a patient's readiness to change and engage in treatment. MI uses an open dialogue to explore whether a patient is ready to commit to treatment. The therapist is nonjudgmental, empathic, and respectful of the patient's current status. An interesting finding is that this intervention appears to have a greater effect on certain minority populations and may be considered a suitable “match” in such cases.

|

Table 5. Meta-Analyses for Other Disorders

Leichsenring and colleagues (68, 69) reported two meta-analyses for a range of disorders and complex disorders treated with psychodynamic therapy and found large effect sizes compared with wait list or treatment as usual. When only RCTs were included, the effect size remained significant and large (69). In addition to this finding, effectiveness research supports the use of long-term psychodynamic therapies in decreasing symptomatic distress and improving interpersonal problems, social adjustment, and self-esteem (69). The last decade has witnessed an emergence of research in psychodynamic therapy, suggesting that this therapy is a viable option for interpersonal and characterological difficulties that cannot be treated by other briefer treatments focusing on symptomatic improvement. Further research may also establish brief dynamic therapies as beneficial alternative treatments in some axis I disorders when other treatments fail.

A group of treatments known as the “third-wave cognitive behavior therapies” have also been investigated for many conditions. Therapies under this umbrella include acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (which incorporates acceptance and mindfulness strategies, together with commitment and behavior change strategies to increase psychological flexibility) for the treatment of depression, anxiety, stress, and addictions; DBT for patients with BPD as discussed above; the cognitive behavior analysis system of psychotherapy (which integrates components of cognitive and psychodynamic therapy) for chronic depression; functional analytic psychotherapy (which incorporates radical behaviorism to in-session verbal behavior) for depression; and integrative behavioral couple therapy (which integrates behavioral couple therapy with emotional acceptance) for couple problems. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated moderate effect sizes for both ACT and DBT, but because of the small number of studies conclusions regarding the other therapies cannot be made at this time (62).

Although not incorporated in recent meta-analyses, two new therapies show promise in the treatment of patients with BPD: systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) and schema-focused therapy. STEPPS is a brief therapy that incorporates CBT, skills training, and systems theory and has been found to be effective in RCTs in the treatment of BPD (70). Schema-focused therapy, a form of CBT that focuses on core beliefs and schemas developed in childhood, has also been found to be helpful in treating patients with BPD (71). Meta-analyses of the future will no doubt include these new forms of treatments and it is hoped that they will offer patients with BDT a wide range of psychotherapeutic options to choose from.

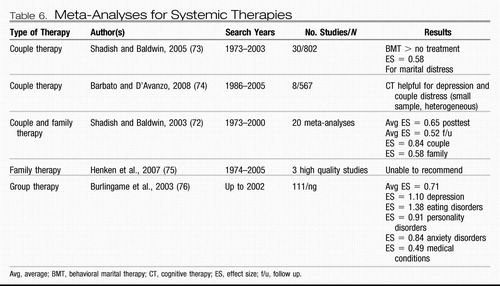

Systemic therapies have also been investigated for patients with psychiatric problems (Table 6). There is strong support for couples therapy as an intervention for couples experiencing relationship distress, with large effect sizes being reported (72). Behavioral marital therapy shows a moderate effect size in the treatment of marital distress (73). Couples therapy has always demonstrated consistently higher effect sizes than family interventions, and this has been attributed to family problems being more intractable and involving more patients. Whether this explains the lower effect sizes seen in family therapy is unclear. Moderate effect sizes have been reported for family therapy as an adjunct in child and adult disorders and in specific family problems (72, 74). However, one meta-analysis has indicated that, based on the few studies, recommendations at this time are difficult to make (75).

|

Table 6. Meta-Analyses for Systemic Therapies

Group interventions minimize the use of resources and offer patients additional benefits such as increased social support and the perception that there are others who struggle with the same illness. Moderate to large effect sizes support the use of many types of group-based interventions in the treatment of several psychiatric disorders (76).

INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES AND DIFFERENTIAL TREATMENT OUTCOME

Although psychotherapies are effective treatments for many patients with psychiatric disorders, not all patients benefit from all treatments. There are probably many reasons for this outcome. First, there is great variability among therapists in their level of skill and expertise in delivering a specific treatment. Therapist competence is an important variable in outcome as it determines the integrity of treatment delivered (77). Although most studies control for this factor, they tend to use novice therapists such as psychology graduate students or psychiatry residents who have yet to develop finely tuned skills in a particular form of therapy. Novice therapists are also known to have more difficulty with more severely ill patients, particularly those who are struggling with developing an alliance with their therapists.

Second, there may be diagnostic issues in that a patient may be receiving a treatment for an illness he or she does not have. For example, treating a patient with dysthymia with a brief course of CBT may not produce the best results (66). Such patients require longer treatment and booster sessions after therapy. Third, there could be significant comorbidity that makes it difficult to focus on a target problem. As discussed above, patients with panic disorder and significant comorbidity have a poorer outcome than those who do not present with comorbidity (48). These patients may require more careful integration of several types of treatment and longer duration of delivery of each treatment. For the practicing psychiatrist “real-world” patients present with extensive comorbidity, longer duration of illness, and prior failures to many forms of treatment. Rarely do patients present with one axis I diagnosis.

Fourth, the patient may be unable to form a therapeutic alliance with the therapist, essential for successful psychotherapy outcome regardless of treatment type. This important variable is discussed at length below. And finally there may be individual factors that are specific to the patient that make him or her unlikely to respond to one form of psychotherapy but more responsive to another. A similar analogy would be depressed patients' differential response to various antidepressants. For whatever reason, some patients may be suitable for one form of psychotherapy and not another, based on multiple factors. Some patients may be more action oriented, preferring homework and behavioral exercises, whereas others may be noncompliant in this area, preferring to talk about their issues and explore their feelings. Identifying these individual variables early may help us match the patient to the treatment and be more efficient in our outcomes.

To explore significant patient variables that predict psychotherapy outcome, PsycINFO and PubMed were searched for the past 20 years using the search terms “patient variables (factors),” “client variables (factors),” predictors,” and “psychotherapy outcome.” Thirteen articles and/or chapters discussing specific patient variables that predicted differential response to psychotherapy were identified. The earliest research identified the patient's readiness to change as a predictor of engagement and outcome in therapy. Four stages of readiness to change have been described, including precontemplative, contemplative, action, and maintenance, with the majority of patients being in the first two stages, either not ready or contemplating change (78). MI assists in identifying the patient's stage and then helps prepare him or her for treatment (79). Patients in the precontemplative and contemplative stages need time to explore the risks and benefits of choosing a course of treatment and benefit from exploratory interventions such as MI, experiential or psychodynamic therapy. Patients in the action stage are more receptive to therapy and are probably good candidates for a specific form of treatment requiring action such as CBT (which involves exposure, cognitive restructuring, and specific exercises) or IPT, which also involves some problem-solving techniques to increase social support (80). Evidence to date indicates that this is an important variable, particularly in the treatment of addictive behaviors such as substance abuse (80). Therefore, readiness to change has been found to be an important variable in determining where to start with a patient. This may also encourage a better therapeutic alliance and increase the probability that a patient will remain in treatment. Additional treatments can be considered after patients have engaged in the initial treatment.

Other individual variables have been found to predict differential response to psychotherapy. Beutler et al. (81) found that patient resistance and reactance level predicted specific responses to certain therapeutic approaches. Patients low on the resistance/reactance variable were described as accepting of interpretations, homework, direction, and authority and generally being open and nondefensive in treatment. These patients generally did well in most treatments. Patients high in resistance and reactance, however, were described as being more resistant to treatment suggestions such as interpretations and prescription of homework. These patients generally valued autonomy, were described as dominant, and had a history of poor response to previous treatment. Patients with this response style did better with nondirective, exploratory therapies, emphasizing self-change (psychodynamic and experiential) and also benefitted from paradoxical interventions if carried out by an expert therapist in a timely fashion (82).

Degree of relatedness has also been found to predict differential response to treatment. Patients found to have a sociotropic style of relating (investment in long-term relationships) did well in supportive-expressive, long-term psychodynamic, and interpersonal therapy (83), whereas those patients with an introjective/autonomous style (values independence and autonomy) did better with psychodynamic and cognitive behavior therapies (83). Likewise, McBride et al. (84) found that attachment styles predicted response to treatment with those insecurely attached responding preferentially to psychodynamic and interpersonal therapies and those avoidantly attached faring better with cognitive therapies. Similarly, personality variables have also been studied with respect to differential outcome to treatment in specific psychiatric disorders with avoidant patients responding better to CBT and obsessional patients faring better with IPT in the treatment of depression (85). Patients with cluster B personality traits show a preferential response to those therapies that are highly structured and provide very clear, rigid boundaries (86).

Other patient variables that have been explored include functional impairment, religion and spirituality, and gender matching. Research to date indicates that severely functionally impaired patients do well with medications first, followed by psychotherapy. However severity of illness does not preclude the use of psychotherapy, although one should proceed with the idea that more time and effort will be required to attain a good outcome. There is no evidence to suggest that matching the patient's religion or gender to those of the therapist is essential for a positive outcome in therapy unless this is specifically requested by the patient (87).

Finally and perhaps new to the field is the contribution of neuroscience in predicting differential outcome to treatment. Imaging studies have shown that patients with OCD who show a decrease in pretreatment orbital-frontal cortical metabolism have a better response to medications, whereas those who show an increase have a better response to CBT (88). Imaging studies have also shown that medications, CBT, and IPT, when effective, all reverse pretreatment abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, the area identified in depression (89). However, different regional effects were observed specific to each treatment. In an intriguing study, Goldapple et al. (90) found that depressed patients who responded to CBT showed a decrease in glucose metabolism in the frontal and parietal regions but an increase in glucose metabolism in the hippocampal region, whereas those depressed patients who responded to paroxetine showed the reverse pattern. Although in its infancy, these studies offer the hope of isolating a neural signature in predicting differential outcome to treatment (89), which is an exciting possibility for the future!

THERAPEUTIC ALLIANCE

Once diagnosis has been established and an evidence-based psychotherapy has been selected with the consideration of individual patient factors, it is important to consider one of the most important variables in psychotherapy outcome: the therapeutic alliance. There is general agreement among therapists of divergent orientations that the therapeutic relationship is fundamental to treatment outcome. Although Freud gave more emphasis to the aspects of the therapeutic relationship that were developmental in origin and transferred to the therapist in the transference relationship, he did describe a collaborative component in the “positive transference,” that permitted the patient to engage in treatment and participate in the work of therapy (91). Zetzel (92) and Greenson (93) further clarified this relationship, pointing to its reality-based components rather than those considered transferential in origin. The notion that the relationship was in itself therapeutic was also advocated by Frank (94). However, it was Bordin (95) who furthered the concept of the therapeutic alliance by emphasizing its importance in all therapies and offering a pantheoretical definition that could be adopted by all theoretical orientations.

Since these original reports, research on the therapeutic alliance has flourished with numerous instruments currently available for assessment. Four decades of research now demonstrate that regardless of the type of psychotherapy, reliably observable aspects of the nature of the therapeutic alliance predict outcome early in treatment (96). Ackerman and Hilsenroth (97) in a recent meta-analysis found that specific therapist attributes and techniques predict a positive therapeutic alliance. Therapists' attributes such as being empathic, warm, genuine, respectful, flexible, experienced, honest, confident, interested, and trustworthy and not authoritarian, controlling, or hostile all promote a positive alliance. Specific therapist techniques such as setting goals, being active, reflective, exploratory, supportive, empathic, and focused, as well as staying on task, are all important in maintaining a strong alliance. In addition, it is critical for the therapist to pay attention to ruptures in the alliance as this too predicts a positive outcome in psychotherapy (97). A positive alliance has also been shown to be important in maintaining medication compliance in pharmacological treatment (98).

Although the ability to form a positive therapeutic alliance is a fundamental skill, there are specific psychotherapies in which more attention is paid to alliance building factors as discussed above. These include the experiential or client-centered therapies (99), Luborsky's (100) supportive-expressive therapy and EFT (101), which integrates client-centered and gestalt techniques. Therefore, before implementing specific therapies or techniques, it is essential to ensure that sufficient attention has been given to the therapeutic alliance with the delivery of these alliance-building skills. Early dropouts or treatment failures could be due to a poor patient-therapist alliance, rather than to the intervention being delivered, whether this is an interpretation, challenging cognitive distortions, encouraging medication compliance, or other therapy-specific intervention. In summary, it is important that that therapist pay special attention to the therapeutic alliance especially early in treatment, as it is crucial to a successful outcome in any form of treatment and most importantly in psychotherapy.

CASE EXAMPLES

After this brief review of the empirical psychotherapy literature, it is prudent to consider how this information can be applied to clinical practice. To assist in this process let us consider two clinical case examples.

Case example 1

A 42-year-old married father with three young children, who is practicing as a full-time lawyer presents with symptoms of chronic social anxiety and acute moderate depression with no suicidal ideation after a recent occupational stressor. His only significant relationship is with his wife. He is very independent in his approach to his work and his life and somewhat avoidant in his relational style. He has taken a variety of medications, none of which he has tolerated well and he would prefer to look at other alternatives. He is sent to you for a psychotherapy consultation. Which psychotherapy would you consider for this man based on the empirical literature?

Answer

First, we need to look at the clinical diagnoses. He is presenting with moderate depression for which many psychotherapies have been found to be effective as discussed above. CBT is effective for social anxiety disorder. This man presents with a high degree of autonomy and an avoidant attachment style. Therefore, CBT would certainly be indicated for depression and the social phobia; however, given his autonomy it would need to be delivered in a very slow, cautious manner without the therapist presenting as highly directive. Time will be required for an alliance to develop so the patient can consider CBT. It would be important to present him with all alternatives to treatment such as IPT, short-term psychodynamic therapy, and others, as well as the possibility of reviewing medication if there is no success with psychotherapy. IPT may be helpful, given that his depression may have been precipitated by a role transition or conflict at work. However, CBT will still be needed for the social anxiety disorder.

Case example 2

A 55-year-old widow presents with unremitting depression since the loss of her husband 2 years previously. She is currently a retired school teacher with two older sons who she sees infrequently. She has friends but she is reluctant to “burden” them with her problems. She has many regrets regarding issues relating to her deceased husband and has not discussed these with anyone. She also presents with long-standing symptoms of OCD, which have also gotten worse. She has medical problems that have made it difficult for her to tolerate antidepressants. She has been sent by her family doctor for a consultation regarding other treatment options.

Answer

A diagnosis of chronic depression and OCD suggests several treatments; however, both conditions are more resistant to treatment and require combined treatments. Chronic depression does suggest the need for combination treatments such as medication and psychotherapy. Perhaps medication could be revisited once she has established a positive alliance with a therapist. Given that her depression occurred in the context of grief and possible unfinished business issues, IPT, EFT, and psychodynamic therapy are all possible treatments to consider. These treatments will help her explore her unfinished business issues with her deceased husband, her distant relationship with both her sons, and her difficulties accessing social support. CBT or specifically exposure and response prevention will be needed to treat her OCD after her depression is addressed as she may be more motivated to deal with this as she gains the necessary energy required to engage in this form of treatment. It will also be important to use a group intervention at some point to help her access social support and look at her bereavement issues in this context. Other considerations are behavioral activation, which will help with scheduling positive activities and exercise.

CONCLUSION

The last decade has witnessed an explosion of research in psychotherapy for patients with psychiatric disorders. As outlined above numerous meta-analyses (or level 1 evidence) have demonstrated moderate to large effect sizes for many forms of psychotherapy such as CBT, IPT, EFT, behavioral activation, DBT, exposure and response prevention, EMDR, STPP, and psychodynamic therapy for psychiatric patients across the lifespan, representing a significant shift in the literature from decades ago. Numerous psychotherapies have been studied for depression, whereas CBT has been studied mainly for patients suffering from anxiety disorders and other conditions. Despite these promising findings, it is well known that not all therapies help all patients. Recent efforts to identify patient variables that can be matched to specific treatments have pointed to personality variables, attachment styles, and patient reactance and resistance in treatment. Although preliminary, it is intriguing to consider various individual variables when one is making treatment decisions.

Although specific therapies for specific disorders and individual variables that predict differential response to treatment dominate the literature, the therapeutic alliance formed between the patient and the psychiatrist continues to be a robust indicator of treatment outcome, indicating yet again that without a sound therapeutic relationship one cannot engage in any form of psychotherapy or other form of treatment with any success at any time. Although this information is well known to the practicing psychiatrist, it is important to know that it is supported by at least three decades of empirical research.

In summary, as clinical psychiatrists we frequently see patients struggle through a particular form of psychotherapy, unable to move forward and unable to use the sessions as we had hoped. This failure may not always be resistance, defense, transference, or homework noncompliance. In such cases it is important to consider several factors:

| 1. | What is the patient's diagnosis or problem? | ||||

| 2. | Are you delivering an evidence-based treatment specific for that diagnosis or problem? | ||||

| 3. | Are there patient variables that might suggest an alternate treatment? | ||||

| 4. | Are there therapeutic alliance issues? | ||||

Since the last issue of Focus dedicated to psychotherapy, much has changed. There have been numerous RCTs for several different psychotherapies, with more than 60 meta-analyses in the past decade alone. Several new psychotherapies have been identified for patients with psychiatric disorders and unique patient characteristics have been investigated to help match patients to specific treatments. Neuroscience also offers exciting possibilities of predicting differential response to treatment. In addition, as already established, the therapeutic relationship continues to be a robust predictor of outcome.

I look forward to the next issue of Focus dedicated to psychotherapy. One wonders what new discoveries will be made by then. It is hoped that empirical research will continue to support new therapies for patients with psychiatric disorders, identify additional patient variables that predict differential response to treatment, and explore therapist variables important in how we deliver psychotherapy, so that we can be more competent general psychiatrists and psychotherapists. Research aimed in this direction will continue to promote the evidence-based practice of psychotherapy and benefit patients struggling with complex psychiatric problems.

PSYCHOTHERAPY LEARNING RESOURCES

| 1. | Online Resources: PsycINFO (this will yield the greater number of publications in psychotherapy research), PubMed, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (key words: meta-analysis, meta-analyses, review) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. | Journals: There are key journals that publish empirical reviews and regular scholarly articles in psychotherapy. This is not a complete list.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. | Annual Meetings: There are many professional meetings that are devoted to psychotherapy. Some of these are the following:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. | Training Institutions: There are many ways to obtain clinical supervision in a specific form of therapy. Distance supervision through webcams now offers a much convenient option. Online searches today yield an abundance of training opportunities. A few examples appear below.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1 Lam RW, Kennedy SH: Using meta-analysis to evaluate evidence: practical tips and traps. Can J Psychiatry 2005; 50:167–174 Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB: Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126:376–380 Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Streiner DL: I have the answer, now what's the question? Why meta-analyses do not provide definitive solutions. Can J Psychiatry 2005; 50:829–831 Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Nathan P, Gorman JM: A Guide to Treatments That Work, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002 Google Scholar

5 Lambert MJ: Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2004 Google Scholar

6 Elkin I, Parloff MB, Hadley SW, Autry JH: NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:305–316 Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Wampold BE, Minami T, Baskin TW, Callen Tierney S: A meta-(re)analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy versus ‘other therapies’ for depression. J Affect Disord 2002; 68:159–165 Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Westen D, Morrison K: A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001; 69:875–899 Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Petrocelli JV: Effectiveness of group cognitive-behavioral therapy for general symptomatology: a meta-analysis. J Spec Group Work 2002; 27:92–115 Crossref, Google Scholar

10 McDermut W, Miller IW, Brown RA: The efficacy of group psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis and review of the empirical research. Clin Psychol 2001; 8:98–116 Google Scholar

11 Elliott R, Greenberg L, Lietaer G: Research on experiential therapies, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th ed. Edited by Lambert MJ, ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2004, pp 493–540 Google Scholar

12 Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L: Behavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2007; 27:318–326 Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, van Oppen P: Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008; 76:909–922 Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Ekers D, Richards D, Gilbody S: A meta-analysis of randomized trials of behavioural treatment of depression. Psychol Med 2008; 38:611–623 Crossref, Google Scholar

15 de Mello MF, de Jesus Mari J, Bacaltchuk J, Verdeli H, Neugebauer R: A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 255:75–82 Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Driessen E, Cuijpers P, de Maat SC, Abbass AA, de Jonghe F, Dekker JJ: The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:25–36 Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L: Problem solving therapies for depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2007; 22:9–15 Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Bell AC, D'Zurilla TJ: Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29:348–353 Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Cuijpers P, Munoz RF, Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM: Psychoeducational treatment and prevention of depression: the “coping with depression” course thirty years later. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29:449–458 Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L: Are individual and group treatments equally effective in the treatment of depression in adults? A meta-analysis. Eur J Psychiatry 2008; 22:38–51 Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Bohlmeijer E, Hollon SD, Andersson G: The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychol Med 2009; 3:1–13 Google Scholar

22 Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C: Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological treatment for depression: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:714–719 Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, Andersson G: Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:1219–1229 Crossref, Google Scholar

24 de Maat SM, Dekker J, Schoevers RA, de Jonghe F: Relative efficacy of psychotherapy and combined therapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2007; 22:1–8 Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Imel ZE, Malterer MB, McKay KM, Wampold BE: A meta-analysis of psychotherapy and medication in unipolar depression and dysthymia. J Affect Disord 2008; 110:197–206 Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM: Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2006; 132:132–149 Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Klein JB, Jacobs RH, Reinecke MA: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: a meta-analytic investigation of changes in effect-size estimates. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46:1403–1413 Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM: Treatments for later-life depressive conditions: a meta-analytic comparison of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1493–1501 Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Bledsoe SE, Grote NK: Treating depression during pregnancy and the postpartum: a preliminary meta-analysis. Res Soc Work Pract 2006; 16:109–120. Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Scott J, Colom F, Vieta E: A meta-analysis of relapse rates with adjunctive psychological therapies compared to usual psychiatric treatment for bipolar disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 10:123–129 Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Williams JMG, Russel I, Russell D: Mindfulness based cognitive therapy: further issues in current evidence and future research. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008; 76:524–529 Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Norton PJ, Price EC: A meta-analytic review of adult cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome across the anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 2007; 195:521–531 Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Hofmann SG, Smits JA: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:621–632 Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Stewart RE, Chambless DL: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009; 77:595–606 Crossref, Google Scholar

35 van Ingen DJ, Freiheit SR, Vye CS: From the lab to the clinic: effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders. Prof Psychol 2009; 40:69–74 Crossref, Google Scholar

36 In-Albon T, Schneider S: Psychotherapy of childhood anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom 2007; 76:15–24 Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Ishikawa S, Okajima I, Matsuoka H, Sakano Y: Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2007; 12:164–172 Crossref, Google Scholar

38 James A, Soler A, Weatherall R: Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 4:CD004690 Google Scholar

39 Abramowitz JS, Whiteside SP, Deacon BJ: The effectiveness of treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther 2005; 36:55–63 Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Watson HJ, Rees CS: Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled treatment trials for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008; 49:489–498 Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Segool NK, Carlson JS: Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments for children with social anxiety. Depress Anxiety 2008; 25:620–631 Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Hendriks GJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, van Balkom AJ: Cognitive-behavioural therapy for late-life anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008; 117:403–411 Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, Westen D: A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 2004; 24:1011–1030 Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Rosa-Alcazar AI, Sanchez-Meca J, Gomez-Conesa A, Marin-Martinez F: Psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2008; 28:1310–1325 Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Mitte K: Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatments for generalized anxiety disorder: a comparison with pharmacotherapy. Psychol Bull 2005; 131:785–795 Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Covin R, Ouimet AJ, Seeds PM, Dozois DJ: A meta-analysis of CBT for pathological worry among clients with GAD. J Anxiety Disord 2008; 22:108–116 Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Mitte K: A meta-analysis of the efficacy of psycho- and pharmacotherapy in panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. J Affect Disord 2005; 88:27–45 Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Sanchez-Meca J, Rosa-Alcazar AI, Marin-Martinez F, Gomez-Conesa A: Psychological treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:37–50 Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, Dutra L, Westen D: A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:214–227 Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Benish SG, Imel ZE, Wampold BE: The relative efficacy of bona fide psychotherapies for treating post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Clin Psychol Rev 2008; 28:746–758 Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Bisson JI, Ehlers A, Matthews R, Pilling S, Richards D, Turner S: Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190:97–104 Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Kornor H, Winje D, Ekeberg Ø, Weisaeth L, Kirkehei I, Johansen K, Steiro A. Early trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy to prevent chronic post-traumatic stress disorder and related symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2008; 8:81 Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Fedoroff IC, Taylor S: Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:311–324 Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Acarturk C, Cuijpers P, van Straten A, de Graaf R: Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2009; 39:241–254 Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, Telch MJ: Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2008; 28:1021–1037 Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Gould RA, Mueser KT, Bolton E, Mays V, Goff D: Cognitive therapy for psychosis in schizophrenia: an effect size analysis. Schizophr Res 2001; 48:335–342 Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, Garety P, Geddes J, Orbach G, Morgan C. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behavior therapy. Psychol Med 2002:763–782 Google Scholar

58 Crawford-Walker CJ, King A, Chan S: Distraction techniques for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 1:CD004717 Google Scholar

59 Zimmermann G, Favrod J, Trieu VH, Pomini V: The effect of cognitive behavioral treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 2005; 77:1–9 Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Leichsenring F, Leibing E: The effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1223–1232 Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Binks CA, Fenton M, McCarthy L, Lee T, Adams CE, Duggan C: Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 1:CD005653 Google Scholar

62 Ost LG: Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther 2008; 46:296–321 Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Thompson-Brenner H, Glass S, Westen D: A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2003; 10:269–287 Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Abbass A, Kisely S, Kroenke K: Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for somatic disorders. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom 2009; 78:265–274 Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Rooke SE, Bhullar N, Schutte NS: Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2008; 28:736–745 Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT: The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev 2006; 26:17–31 Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR: Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005; 1:91–111 Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Leichsenring F, Rabung S, Leibing E: The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in specific psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:1208–1216 Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Leichsenring F, Rabung S: Effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2008; 300:1551–1565 Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Blum N, St. John D, Pfohl B, Lyle Stuart S, McCormick B, Allen J, Arndt S, Black D: Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) for outpatient with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow up. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:468–478 Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, van Tilburg W, Dirksen C, van Asselt T, Kremers I, Nadort M, Arntz A: Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs. transference-focused therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:649–658 Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Shadish WR, Baldwin SA: Meta-analysis of MFT interventions. J Marital Fam Ther 2003; 29:547–570 Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Shadish WR, Baldwin SA: Effects of behavioral marital therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005; 73:6–14 Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Barbato A, D'Avanzo B: Efficacy of couple therapy as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. Psychiatr Q 2008; 79:121–132 Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Henken HT, Huibers MJ, Churchill R, Restifo K, Roelofs JJ: Family therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 3:CD006728 Google Scholar

76 Burlingame GM, Fuhriman A, Mosier J: The differential effectiveness of group psychotherapy: a meta-analytic perspective. Group Dynamics 2003; 7:3–12 Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Watkins JT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Elkin I: Therapist competence and patient outcome in interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:496–501 Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC: The Transtheoretical Approach, in Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration, 2nd ed. Edited by Norcross JC, Goldfried MR. New York, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp 147–171 Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M: A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72:1050–1062 Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC: In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 1992; 47:1102–1114 Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Beutler LE, Engle D, Mohr D, Daldrup RJ, Bergan J, Meredith K, Merry W: Predictors of differential response to cognitive, experiential, and self-directed psychotherapeutic procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:333–340 Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Beutler LE, Harwood TM, Bertoni M, Thomann J: Systematic treatment selection and prescriptive therapy, in A Casebook of Psychotherapy Integration, 1st ed. Edited by in: Sticker G, Gold J. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2006, pp 29–41 Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Blatt SJ, Shahar G, Zuroff DC: Anaclitic (sociotropic) and introjective (autonomous) dimensions. Psychotherapy 2001; 38:449–454 Crossref, Google Scholar

84 McBride C, Atkinson L, Quilty L, Bagby RM: Attachment as moderator of treatment outcome in major depression: a randomized control trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus cognitive behavior therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006; 74:1041–1054 Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Barber JP, Muenz LR: The role of avoidance and obsessiveness in matching patients to cognitive and interpersonal psychotherapy: empirical findings from the Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:951–958 Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Smith-Benjamin L, Karpiak C: Personality disorders, in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients, 1st Ed. Edited by Norcross JC. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp 423–439 Google Scholar

87 Sue S, Lam A: Culture and demographic diversity, in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients, 1st Ed. Edited by Norcross JC. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp 401–422 Google Scholar

88 Brody AL, Saxena S, Schwartz JM, Stoessel PW, Maidment K, Phelps ME, Baxter LR Jr. FDG-PET predictors of response to behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy in obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res 1998; 84:1–6 Crossref, Google Scholar

89 Frewen PA, Dozois DJ, Lanius RA: Neuroimaging studies of psychological interventions for mood and anxiety disorders: empirical and methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev 2008; 28:228–246 Crossref, Google Scholar

90 Goldapple K, Segal Z, Garson C, Lau M, Bieling P, Kennedy S, Mayberg H: Modulation of cortical-limbic pathways in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2–4; 61:34–41 Crossref, Google Scholar

91 Freud S: On the beginning of treatment: further recommendations on the technique of psychoanalysis (1912–1913), Complete Psychological Works, standard ed, vol 12. London, Hogarth Press, 1953, pp 122–144 Google Scholar

92 Zetzel ER: Current concepts of transference. Int J Psychoanal 1956; 37:369–376 Google Scholar

93 Greenson RR: The working alliance and the transference neuroses. Psychoanal Q 1965; 34:155–181 Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Frank, JD: Persuasion and Healing. Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1961 Google Scholar

95 Bordin ES: The working alliance: basis for a general theory of psychotherapy.

96 Horvath AO: The alliance. Psychotherapy 2001; 38:365–372 Crossref, Google Scholar

97 Ackerman SJ, Hilsenroth MJ: A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clin Psychol Rev 2003; 23:1–33 Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Weiss KA, Smith TE, Hull JW, Piper AC, Huppert JD: Predictors of risk of nonadherence in outpatients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Schizophr Bull 2002; 28:341–349 Crossref, Google Scholar

99 Rogers CC: Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications, and Theory. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1965 Google Scholar

100 Luborsky L: Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy: a manual for supportive-expressive treatment. New York, Basic Books, 1984 Google Scholar

101 Greenberg LS, Watson JC: Emotion-Focused Therapy for Depression. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2006 Google Scholar