Preventing Excessive Weight Gain in Adolescents: Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Binge Eating

Abstract

The most prevalent disordered eating pattern described in overweight youth is loss of control (LOC) eating, during which individuals experience an inability to control the type or amount of food they consume. LOC eating is associated cross-sectionally with greater adiposity in children and adolescents and seems to predispose youth to gain weight or body fat above that expected during normal growth, thus likely contributing to obesity in susceptible individuals. No prior studies have examined whether LOC eating can be decreased by interventions in children or adolescents without full-syndrome eating disorders or whether programs reducing LOC eating prevent inappropriate weight gain attributable to LOC eating. Interpersonal psychotherapy, a form of therapy that was designed to treat depression and has been adapted for the treatment of eating disorders, has shown efficacy in reducing binge eating episodes and inducing weight stabilization among adults diagnosed with binge eating disorder. In this paper, we propose a theoretical model of excessive weight gain in adolescents at high risk for adult obesity who engage in LOC eating and associated overeating patterns. A rationale is provided for interpersonal psychotherapy as an intervention to slow the trajectory of weight gain in at-risk youth, with the aim of preventing or ameliorating obesity in adulthood.

(Reprinted with permission from Obesity June 2007; 15:1345–1355)

INTRODUCTION

A number of studies have found that the risk of an overweight child or adolescent becoming an obese adult rises with both age and degree of obesity (1–6). In addition to its immediate negative effects on health, overweight in youth also increases the long-term risk of adult morbidity and mortality (7), independent of adult obesity (8, 9). Furthermore, overweight youth suffer from more social stigmatization and isolation (10) and are at increased risk for psychological problems, such as greater depressive symptoms and anxiety, compared with their non-overweight peers (11–14).

Binge eating, marked by an individual ingesting large amounts of food while experiencing loss of control (LOC) over eating (15), is the most commonly identified abnormal eating behavior among obese adults. Binge eating disorder (BED), a putative eating disorder in the DSM-IV-TR (15), is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating accompanied by dysfunctional eating attitudes and marked distress (15). Adults with BED suffer from higher levels of physical disabilities, poorer physical health, lower quality of life (16, 17), and more psychiatric disturbance (18–20) than obese adults without an eating disorder, in addition to having disordered eating psychopathology at levels similar to those with bulimia nervosa (18, 21). Moreover, BED has been associated with social impairment and poor interpersonal functioning (17, 22–24). Because individuals with BED do not regularly engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviors, BED and recurrent binge eating is often associated with excess body weight and obesity (19, 25). Repeated binge eating has also been shown to predict the development of inappropriate weight gain and obesity in a community sample of adults (26). Finally, some (27–29), but not all (30–32) studies have shown that persons with BED have poorer response to obesity treatment or more rapid regain of lost weight after treatment than those without an eating disorder.

The incidence of full-syndrome BED seems to be quite low in children. However, prevalence estimates should be considered with caution because developmentally appropriate techniques to measure binge eating among children have not yet been fully established. LOC eating episodes, which may consist of an objectively or subjectively large amount of food and occur with less frequency than required by the full DSM-IV-TR BED criteria (15), seem to be more common in overweight youth than their non-overweight peers (13, 33). Moreover, studies of non-treatment-seeking children have found that the experience of LOC during eating, regardless of the amount of food ingested, seems to be more salient in describing pathologic eating in children than classic binge episodes that require the consumption of a large amount of food (13, 33–35). This may, in part, be caused by difficulty in distinguishing what constitutes a “large amount of food” among growing children with varying nutritional needs (36). Furthermore, rigorous interview methods used to assess aberrant eating patterns require conservative coding of an eating episode size (e.g., if an amount is ambiguously large, it is considered “not large”), often minimizing the distinction between binge eating and LOC eating in the absence of an unambiguously large amount of food (36). Youth engaging in even limited numbers of LOC eating episodes suffer from increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, greater disturbed eating cognitions, more parent reported problems, and significantly higher adiposity compared with children who do not engage in LOC eating episodes (13, 33, 34, 37).

The prevalence of subthreshold binge and LOC eating among overweight adolescents seems to be substantial; in weight loss treatment-seeking samples, the estimates range from 20% (38) to ∼30% (39). Even among school and community samples, estimates of subthreshold binge eating range from 6% to 40% among adolescents (40–44). Consistent with the adult BED literature, studies have found that adolescents who report binge eating at non-diagnostic levels have increased eating-related and general psychological distress and lower self-esteem compared with non-binge eaters. In samples of overweight, treatment-seeking adolescents, binge eating severity has been positively associated with depression and anxiety (45) and negatively correlated with self-esteem and body esteem (38, 39, 46).

Although a number of studies suggest a relationship between binge eating and obesity in children, they are limited by their cross-sectional nature and are not informative regarding causation. However, longitudinal studies have found binge eating episodes to prospectively predict increased weight gain. In a large study of boys and girls (9 to 14 years), Field et al. (47) found that binge eating predicted increases in BMI in boys only, after accounting for baseline BMI. Binge eating predicted weight gain and the onset of obesity in samples of adolescent girls in two prospective studies (48, 49). In a study of 146 boys and girls (6 to 12 years at baseline), all of whom were overweight or at high risk for overweight because of a family history of obesity, binge eating at baseline predicted an additional 15% increase in body fat mass 4 years later, adjusted for the contribution of baseline fat mass (50). Given the excess energy intake associated with binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors, these data suggest a possible intervention point for preventing the development of continued inappropriate weight gain: treatment of binge and LOC eating behaviors.

OBESITY IN PREVENTION

Although family-based behavioral treatment of obesity in school-aged children has shown some long-term efficacy (51), studies of adolescent and adult weight loss and maintenance have been less successful (51–53), further emphasizing the need for early intervention. Prevention has been suggested as the most important approach to decreasing the obesity epidemic (54). However, trials of obesity prevention programs have been met with limited success. Prevention programs have targeted behaviors that have been associated with overweight (e.g., television watching, soft drink consumption), or youths who are already overweight (55, 56). However, none have targeted youths who are at high risk for increased weight gain over time based on both current weight status and disturbed eating behaviors. Behavioral factors, such as LOC eating (subjectively or objectively large binge episodes), are attractive targets because they may be amenable to change. By reducing LOC eating episodes, inappropriate weight gain attributable to LOC eating may be prevented.

The Strategic Plan for the NIH Obesity Research (57) supports the proposition that coordinating the treatment of obesity and eating disorders may serve as a promising form of intervention. The plan notes that factors underlying binge eating in children may offer effective strategies for the prevention of obesity in high-risk populations and recommends that “the impact of strategies that simultaneously address the prevention of eating disorders as well as obesity” be determined. To date, two randomized, controlled trials testing programs for the prevention of obesity in adolescents, but which did not specifically target disordered eating, have resulted in reductions in eating disorder pathology. The first program, which included dance classes and a family-based intervention to reduce television viewing for girls, reported that participants in the treatment group trended toward greater weight loss and reported less concern about weight compared with the control group (58). Results from the second study, “Planet Health” (59), a school-based intervention focused on reducing inactivity, increasing physical activity, and augmenting healthful food consumption, reported reductions in obesity among girls in the treatment group (59). They also found that the treatment group reported fewer new cases of extreme compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting and laxative use (60). These findings help to mitigate the concerns that obesity prevention programs will increase the incidence of eating disorders.

Although the impact of obesity prevention and treatment programs on eating disorders has been studied, only one research team has tested the efficacy of an eating disorder intervention in preventing obesity. Stice et al. (61) found that healthy weight adolescent girls who participated in a dissonance-based intervention designed to reduce thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms were less likely to become obese 1 year later compared with girls assigned to control conditions. However, to our knowledge, no study has specifically targeted a prospectively identified risk factor for the prevention of excessive weight gain in youth at high risk for adult obesity. Studies testing the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy alone (62–68) or augmented with behavioral weight loss (69, 70), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (64, 65), and other forms of specialized therapies (68, 71) for the treatment of BED in overweight adults have reported reductions in binge eating episodes, with abstinence rates ranging from 33% to 77% at final assessment. An unexpected finding of psychological treatment for BED has been that individuals with BED who cease to binge eat tend to maintain their body weight during and/or after treatment. In ∼50% of studies including psychotherapy, participants who remained abstinent from binge eating lost modest amounts of weight by their last assessment (64, 65, 69, 70, 72). In all but one study (63), individuals who did not remain abstinent from binge eating continued to gain weight. Despite these data, recent reviews have indicated that appreciable weight loss does not occur with psychotherapy for BED and that clinical trials are needed to obtain better measures of weight loss and maintenance (73).

Another potential limitation of targeting binge eating for weight gain prevention is cross-sectional data in children suggesting that many individuals with LOC eating report having become overweight before their first LOC episode (34, 74). Furthermore, a history of childhood obesity is often recalled by adults with BED (75). For such individuals, variables other than binge eating (e.g., genetics, family environment) are likely responsible for excessive weight gain and may be less responsive to a psychological treatment targeting binge eating. However, binge eating may serve as a maintaining factor for excess body weight in such persons. In contrast, one retrospective study of adults with BED found that most individuals reported being of normal weight before their first binge episode that generally occurred during adolescence (76). Moreover, one prospective study found that 79% of adults with BED were not obese at baseline (26), and Stice et al. (48, 49) found binge eating among adolescent girls to predict obesity onset in two longitudinal studies. As such, decreasing weight gain attributable to binge eating patterns among growing individuals who are at high risk for accelerated weight gain, but not severely overweight, may serve as a promising form of intervention.

Interpersonal theory, developed from the teachings of Sullivan and Meyer, posits that psychiatry involves the scientific study of people and their environment rather than the exclusive study of either the mind or of society in isolation (77, 78). Specifically, Sullivan speculated that individual interpersonal patterns may either foster self-esteem or result in hopelessness, anxiety, and psychopathology. Bowlby extended on Sullivan's work by acknowledging the influence of early relationships on subsequent interpersonal functioning and psychopathology (79). Thus, IPT is derived from a theory in which interpersonal functioning is recognized as a critical component of psychological adjustment and well being (80).

IPT, originally developed for the treatment of depression in adults, is a brief therapy that focuses on improving interpersonal functioning (and, in turn, depressive symptoms) by relating symptoms to interpersonal problem areas and developing strategies for dealing with these problems (81). The primary aims of IPT are to identify and treat an individual's depressive symptoms and one or more of the associated problem areas. Specifically, the problem areas frequently associated with depression include grief (complicated bereavement after death), interpersonal role disputes (conflict with a parent, sibling, close friend, classmate, etc.), role transitions (e.g., moving to a new school, parents divorcing, other family changes), and interpersonal deficits (social isolation or chronically poor relationships) (81, 82). IPT focuses on current as opposed to past relationships and, in concert with this approach, makes no assumptions about the etiology of depression.

Treatment is administered in three phases. In brief, the initial phase involves assessment of the psychiatric disturbance, psychoeducation about the nature of the illness, and an assessment of the individual's interpersonal relationships. During this phase, the “sick role” is assigned to identify patients as in need of help, to relieve them of additional social pressures, and to elicit their cooperation in the recovery process (83). The middle phase focuses on the identified interpersonal problem areas and associates the psychiatric disturbance with these problems. The termination phase involves evaluation and consolidation of therapeutic gains, acknowledgment of feelings associated with the end of treatment, and plans to maintain improvements while remaining work is outlined (83). IPT has shown efficacy in the treatment of various types of mood disorders and several non-mood disorders (82). For a complete description of IPT, see Weissman et al. (82).

Building on the work in depressed adults, IPT was modified for adolescent depression (84). Given the similarities between adolescent and adult depression and the social impairment and interpersonal difficulties associated with teen depression (84), it is not surprising that IPT for depressed adolescents has proven efficacious in randomized trials (85–87). IPT for adolescents is a 12-week, once-a-week therapy that, similar to IPT for adults, aims at reducing depressive symptoms and addresses interpersonal problems associated with the onset of depression. The problem areas remain the same across both treatments (88). Modifications from IPT for adults include the adaptation of the “limited sick role,” a discussion about the specific role transition teens experience as a result of family structural change, and inclusion of a flexible parent component. Furthermore, the treatment objectives specifically “take into account developmental tasks, including individuation, establishment of autonomy, development of interpersonal relations with members of the opposite sex and with potential romantic partners, coping with initial experiences amid death and loss, and managing peer pressure” (88). Therapeutic techniques are geared toward the developmental stage and, thus, include use of mood rating scales and work involving basic social skills, direct perspective-taking, and negotiation (88).

More recently, Young and Mufson (89, 90) have adapted IPT for depressed adolescents to a prevention program for teens at high risk for full-syndrome depression. IPT-adolescent skills training (IPT-AST) is an 8-week, once-a-week group program that emphasizes psychoeducation and skill development and focuses on interpersonal issues surrounding the types of difficulties that adolescents encounter on a day-to-day basis. IPT-AST broadly addresses conflicts and transitions that are common to teens and instructs participants to use interpersonal strategies that may be applied to a number of relationships. Preliminary findings suggest that IPT-AST is effective in reducing depressive symptoms and the likelihood of major depressive disorder development (91).

In the late 1980s, IPT was successfully modified for patients with bulimia nervosa (92) and shortly thereafter adapted into a group format for individuals with BED (65, 93). Both adaptations strictly adhered to the original IPT manual with the exception that the interpersonal context focused on the maintenance of the eating disorder as opposed to depression (65, 92). In concert with interpersonal theory, it is posited that binge eating occurs in response to difficult interpersonal interactions, feelings of loneliness, or other negative emotions (94). Indeed, individuals with binge eating often struggle with social and interpersonal deficits (24), and, thus, it is perhaps not surprising that IPT has been shown to be efficacious in reducing binge eating and its associated psychopathology among adults with BED (64, 65). Specifically, IPT for BED is a 15- to 20-week, once-a-week treatment that targets binge eating by directly addressing the social and interpersonal deficits proposed to cause and maintain binge eating (80). In all other respects, IPT for BED differs little from IPT for depression.

In adapting IPT for BED, Wilfley et al. (93) successfully modified the treatment to be delivered in a group format. IPT is particularly suitable for a group modality because it offers an ideal setting for patients to address interpersonal skills and discuss and share their social difficulties within the safe confines of the therapeutic environment (80, 95). Because the interpersonal group is a social entity, it provides members with an “interpersonal laboratory” where they can engage socially while therapists can directly observe each patient's interpersonal style (80, 95). Therapists can provide direct feedback to members while encouraging them to attend to their own behaviors and recognize communication techniques that may be similar to those of other patients (80, 95). The group also provides members with the opportunity to experiment with, and practice, newly acquired skills with peers in the group by role-playing different communication skills such as clarification of the problem, elicitation of another person's point of view, and expression of their own feelings. Ultimately, therapists and members use the group milieu to examine and correct interpersonal difficulties that perpetuate binge eating (80) and other psychiatric disturbances.

Following the group modification of Wilfley et al. (80, 93), Mufson et al. (95) successfully adapted IPT to be delivered in a group format to depressed adolescents. A randomized effectiveness study of IPT for depressed adolescents in school-based health clinics is currently underway. Presently, in their ongoing prevention trial, Young and Mufson (90) are administering IPT-AST in a group format.

Although IPT has shown efficacy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa and BED, it should be noted that, despite evidence that individuals with anorexia nervosa have impaired interpersonal relationships and dysfunctional communication patterns (96), IPT was ineffective in the treatment of the disorder in one study (97). In a study comparing IPT and cognitive behavior therapy to a control comparison (non-specific supportive clinical management), IPT was associated with either modest or no improvement, whereas the control treatment proved to be the most effective of the three psychotherapies (97). Such findings may be the result of the contrasting nature of a restricting eating disorder and those involving binge eating. However, more studies are needed to test IPT for the treatment of anorexia nervosa.

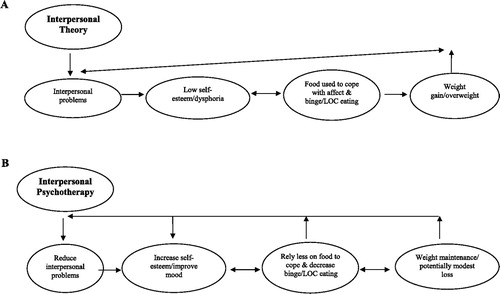

IPT for LOC eating may serve to slow the trajectory of weight gain in overweight or at-risk-for-overweight adolescents who are susceptible to accelerated weight gain because of their disturbed eating patterns. It has been suggested that treatments for BED may offer a potential mechanism in slowing the increase of already epidemic rates of obesity in the United States (98). Because many adults with BED are already obese (19), targeting adolescents who are at high risk for overweight or only slightly overweight (BMI between the 75th and 97th percentiles) and treating them with IPT may serve to reduce inappropriate weight gain in individuals who are still physically developing and whose degree and duration of obesity is more amenable to a preventative intervention. Figure 1 A and B shows the theoretical framework of the proposed intervention. In brief, interpersonal theory posits that interpersonal problems lead to low self-esteem and low mood. Food is used to cope with negative affect and LOC eating ensues. This causes excessive weight gain and overweight, which reinforces interpersonal problems (Figure 1A).

LOC, Loss of Control.

Use of food for coping (emotional eating) may have a biological basis. There are some data to support a physiological role for food (either specific macronutrients, such as carbohydrate, or types of foods such as sweet/fat “dessert” foods) in ameliorating negative affective states (99, 100). More recent studies are investigating the role of the opioid and dopaminergic systems in initiating or sustaining overeating episodes, particularly those caused by emotional eating (101–103). IPT is posited to reduce interpersonal problems, which may result in increases in self-esteem and less reliance on food to cope. As such, LOC eating decreases and the pattern of excessive weight gain is curbed (Figure 1B). There is precedent for a psychotherapeutic approach to ameliorate abnormalities in brain function. Cognitive behavior therapy has been shown to induce changes in brain blood flow similar to that seen with the use of pharmacotherapy in patients with both phobias (104, 105) and obsessive-compulsive disorders (106), suggesting a convergence of pathways through which the impact of these treatments is mediated (107). Changes in regional brain flow in patients treated for depressive disorders with both cognitive behavior therapy (108) and IPT (109, 110) have also been reported. In these cases, the findings are more complex, with drug treatment and psychotherapy activating different cerebral areas, suggesting that psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may act through differing pathways (107).

A number of factors suggest that IPT may be particularly appropriate for adolescents at high-risk for adult obesity. A primary reason is that youth frequently use peer relationships as a crucial measure of self-evaluation (111). Because overweight teens are at risk for appearance-related teasing, rejection, and social isolation (10), they are more likely to experience negative feelings about themselves, particularly regarding their body shape and weight, compared with healthy weight adolescents (112–114). Thus, the social isolation that overweight teens report may be directly targeted by IPT. Indeed, IPT has been shown to decrease negative affect and improve interpersonal and social functioning in depressed adolescents (86). Moreover, recent studies suggest that LOC eating among youth is associated with eating in response to emotions (37), including anger, anxiety, frustration, and depression (115). In studies of adolescents, emotional eating is significantly correlated with constructs of disturbed eating (116, 117) and symptoms of depression and anxiety (117). Data also suggest that emotional eating may be associated with overweight among youth (118) and predictive of overeating in cross-sectional structural models (117). IPT for BED is efficacious at reducing eating in response to negative affect and disordered eating psychopathology in adults (64, 65). Another psychotherapy targeting emotion regulation, namely dialectical behavior therapy, has also been effective in the treatment of BED (71) and might be a reasonable approach for weight gain prevention. However, unlike dialectical behavior therapy, IPT approaches negative affect through addressing social interactions. Considerable literature exists implicating interpersonal sensitivity and difficulties as a common component among individuals with bulimic tendencies (24, 119–122). Measurable findings from two studies involving interactive paradigms suggest that interpersonal distress may trigger overeating (24, 123) and potentially perpetuate binge eating. Furthermore, a number of longitudinal studies have found depressive symptoms to predict weight gain and obesity onset in children and adolescents (124–127). Thus, the proven efficacy of IPT in decreasing depression and depressive symptoms may serve to decrease an additional risk factor for inappropriate weight gain. Finally, IPT is posited to increase social support, which has been shown to increase weight loss and improve weight maintenance in overweight adults (128). Thus, IPT may be a particularly suitable prevention approach for teens at high risk for adult obesity who endorse LOC eating patterns.

IPT FOR THE PREVENTION OF INAPPROPRIATE WEIGHT GAIN

Currently, a pilot study is underway comparing IPT for the prevention of inappropriate weight gain (IPT-WG) to a standard health education program for teens at high risk for adult obesity. In our pilot test of IPT-WG, adolescent girls (12 to 17 years) have a BMI between the 75th and 97th percentile for age and sex (129). Although the current criterion for youth at-risk-for-overweight is a BMI ≥85th percentile (130), a prospective study found that, for children between the 75th and 84th percentile, 35% became overweight and 36% became obese in adulthood (2). Moreover, Field et al. (1) found that youth (8 to 15 years) between the 75th and 84th BMI percentile were 20 times more likely to become overweight 8 to 15 years later compared with those below the 50th percentile. Only adolescents up to the 97th percentile are targeted, because individuals with more severe overweight are at greater risk for obesity-related health comorbidities (131) and, thus, may need more intensive weight loss treatment. Both girls who do and do not endorse symptoms of LOC are included to determine whether IPT-WG decreases the likelihood of excessive weight gain attributable to LOC eating.

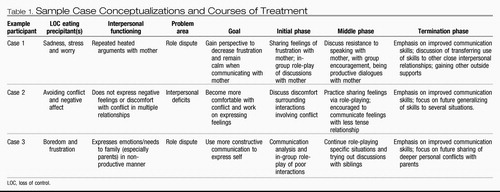

Similar to IPT for eating disorders, the focus of IPT-WG expands on IPT-AST to link negative affect to overeating, LOC eating, or other times when individuals eat in response to cues other than hunger. As such, the pretreatment session involves reviewing the participant's current body weight and eating patterns that place her at high risk for excessive weight gain and adult obesity. Psychoeducation about the relationship between adult obesity and impaired health, psychological and social functioning is discussed. During the pre-treatment meeting and throughout the group sessions, participants are encouraged to link their interpersonal interactions and mood to their eating patterns and overconcern about shape and weight. After IPT-WG or health education, girls' BMI percentile and body composition are being tracked for 1 year after the initiation of the intervention. Ultimately, by finding avenues to improve interactions with parents and peers and subsequently developing more satisfying relationships through IPT-WG, it is possible that overweight or at-risk-for-overweight teens may improve their self-esteem and mood while reducing their reliance on disturbed eating patterns to cope with negative interactions and emotions. In turn, we hypothesize that such individuals will be less likely to gain excessive weight attributable to LOC eating. Table 1 shows the conceptualization and course of treatment for sample cases.

|

Table 1. Sample Case Conceptualizations and Courses of Treatment

SUMMARY

In an effort to slow the trajectory of weight gain in adolescents who are at high risk for adult obesity and who engage in LOC eating episodes, we hypothesize that a new application of IPT, based on the work of Young and Mufson with depressed adolescents and the adaptation of Wilfley et al. to a group modality for adults with BED, may be effective in reducing inappropriate weight gain attributable to loss of control eating. IPT for the prevention of excessive weight gain focuses on increasing interpersonal skills and improving relationships with the aim of reducing binge and loss of control eating. Furthermore, because of IPT's efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms and eating and weight-related psychopathology, applying this prevention modality may serve to reduce the distress surrounding loss of control eating and potentially prevent the concurrent development of full-syndrome eating disorders.

1 Field AE, Cook NR, Gillman MW. Weight status in childhood as a predictor of becoming overweight or hypertensive in early adulthood. Obes Res. 2005; 13: 163– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Freedman DS, Khan LK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2001; 108: 712– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Inter-relationships among childhood BMI, childhood height, and adult obesity: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004; 28: 10– 6.Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, Roche AF. Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002; 76: 653– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997; 337: 869– 73.Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Williams S. Overweight at age 21: the association with body mass index in childhood and adolescence and parents' body mass index. A cohort study of New Zealanders born in 1972–1973. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001; 25: 158– 63.Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Gunnell DJ, Frankel SJ, Nanchahal K, Peters TJ, Davey Smith G. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular mortality: a 57-y follow-up study based on the Boyd Orr cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998; 67: 1111– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Must A, Strauss RS. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999; 23( Suppl 2): S2– 11.Google Scholar

9 van Dam RM, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hu FB. The relationship between overweight in adolescence and premature death in women. Ann Intern Med. 2006; 145: 91– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Social marginalization of overweight children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003; 157: 746– 52.Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Csabi G, Tenyi T, Molnar D. Depressive symptoms among obese children. Eat Weight Disord. 2000; 5: 43– 5.Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Stradmeijer M, Bosch J, Koops W, Seidell J. Family functioning and psychosocial adjustment in overweight youngsters. Int J Eat Disord. 2000; 27: 110– 4.Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004; 72: 53– 61.Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Tershakovec AM, Weller SC, Gallagher PR. Obesity, school performance and behaviour of black, urban elementary school children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994; 18: 323– 7.Google Scholar

15 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.Google Scholar

16 de Zwaan M, Mitchell J, Howell L, et al. Two measures of health-related quality of life in morbid obesity. Obes Res. 2002; 10: 1143– 51.Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychol Med. 2001; 31: 1455– 66.Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Wilfley DE, Friedman MA, Dounchis JZ, Stein RI, Welch RR, Ball SA. Comorbid psychopathology in binge eating disorder: relation to eating disorder severity at baseline and following treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000; 68: 641– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Yanovski SZ, Nelson JE, Dubbert BK, Spitzer RL. Association of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity in obese subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1993; 150: 1472– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Mussell MP, Mitchell JE, de Zwaan M, Crosby RD, Seim HC, Crow SJ. Clinical characteristics associated with binge eating in obese females: a descriptive study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996; 20: 324– 31.Google Scholar

21 Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Binge eating disorder: a need for additional diagnostic criteria. Compr Psychiatry. 2000; 41: 159– 62.Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Crow SJ, Stewart Agras W, Halmi K, Mitchell JE, Kraemer HC. Full syndromal versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder: a multi-center study. Int J Eat Disord. 2002; 32: 309– 18.Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Wilfley D, Wilson G, Agras W. The clinical significance of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2003; 34( Suppl): S96– 106.Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Steiger H, Gauvin L, Jabalpurwala S, Seguin JR, Stotland S. Hypersensitivity to social interactions in bulimic syndromes: relationship to binge eating. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999; 67: 765– 75.Crossref, Google Scholar

25 de Zwaan M. Binge eating disorder and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001; 25( Suppl l): S51– 5.Google Scholar

26 Fairburn C, Cooper Z, Doll H, Norman PM. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000; 57: 659– 65.Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, Wing RR. Binge status as a predictor of weight loss treatment outcome. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999; 23: 485– 93.Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Yanovski SZ, Sebring NG. Recorded food intake of obese women with binge eating disorder before and after weight loss. Int J Eat Disord. 1994; 15: 135– 50.Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, et al. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004; 28: 1124– 33.Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Gladis MM, Wadden TA, Vogt R, Foster G, Kuehnel RH, Bartlett SJ. Behavioral treatment of obese binge eaters: do they need different care? J Psychosom Res. 1998; 44: 375– 84.Crossref, Google Scholar

31 LaPorte DJ. Treatment response in obese binge eaters: preliminary results using a very low calorie diet (VLCD) and behavior therapy. Addict Behav. 1992; 17: 247– 57.Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA. Response of obese binge eaters to treatment by behavior therapy combined with very low calorie diet. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992; 60: 808– 11.Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Morgan CM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Jorge MR, Yanovski JA. Loss of control over eating, body fat, and psychopathology in normal weight and overweight children.

34 Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2005; 38: 112– 22.Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Morgan C, Yanovski S, Nguyen T, et al. Loss of control over eating, adiposity, and psychopathology in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2002; 31: 430– 41.Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Tanofsky-Kraff M. Binge eating among children and adolescents. In: Jelalian E, Steele R, eds. Handbook of Child and Adolescent Obesity. New York: Springer Publishing; 2007.Google Scholar

37 Goossens L, Braet C, Decaluwe V. Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behav Res Ther. 2007; 45: l– 9.Google Scholar

38 Isnard P, Michel G, Frelut ML, et al. Binge eating and psychopathology in severely obese adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2003; 34: 235– 43.Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Decaluwe V, Braet C, Fairburn CG. Binge eating in obese children and adolescents. Int J Eat Disordie. 2003; 33: 78– 84.Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Johnson WG, Rohan KJ, Kirk AA. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating in white and African American adolescents. Eat Behav. 2002; 3: 179– 89.Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicity. J Adolesc Health. 2002; 31: 166– 75.Crossref, Google Scholar

42 French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Downes B, Resnick M, Blum R. Ethnic differences in psychosocial and health behavior correlates of dieting, purging, and binge eating in a population-based sample of adolescent females. Int J Eat Disord. 1997; 22: 315– 22.Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Greenfeld D, Quinlan DM, Harding P, Glass E, Bliss A. Eating behavior in an adolescent population. Int J Eat Disord. 1987; 6: 99– 111.Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Resnick MD, Blum RW. Psychosocial concerns and weight control behaviors among overweight and nonoverweight Native American adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997; 97: 598– 604.Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, et al. Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007; 32: 95– 105. Epub 2006 Jun 25Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Berkowitz R, Stunkard AJ, Stallings VA. Binge-eating disorder in obese adolescent girls. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993; 699: 200– 6.Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003; 112: 900– 6.Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Stice E, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999; 67: 967– 74.Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: a 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychol. 2002; 21: 131– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cohen ML, Yanovski SZ, et al. A prospective study of psychological predictors of body fat gain among children at high risk for adult obesity. Pediatrics. 2006; 117: 1203– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol. 1994; 13: 373– 83.Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Epstein LH, Valoski AM, Kalarchian MA, McCurley J. Do children lose and maintain weight easier than adults: a comparison of child and parent weight changes from six months to ten years. Obes Res. 1995; 3: 411– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Jelalian E, Saelens BE. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: pediatric obesity. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999; 24: 223– 48.Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Styne DM. A plea for prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003; 78: 199– 2007.Crossref, Google Scholar

55 American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: individual-, family-, school-, and community-based interventions for pediatric overweight. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 106: 925– 45.Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: the skinny on interventions that work. Psychol Bull. 2006; 132: 667– 91.Crossref, Google Scholar

57 National Institutes of Health Obesity Research Task Force. Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.Google Scholar

58 Robinson TN, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, et al. Dance and reducing television viewing to prevent weight gain in African-American girls: the Stanford GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003; 13( l Suppl l): S65– 77.Google Scholar

59 Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999; 153: 409– 18.Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Austin SB, Field AE, Wiecha J, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. The impact of a school-based obesity prevention trial on disordered weight-control behaviors in early adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005; 159: 225– 30.Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Stice E, Shaw H, Burton E, Wade E. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: a randomized efficacy trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006; 74: 263– 75.Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005; 43: 1509– 25.Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry. 2005; 57: 301– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Wilfley D, Welch R, Stein R, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002; 59: 713– 21.Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Telch CF, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the nonpurging bulimic individual: a controlled comparison. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993; 61: 296– 305.Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Eldredge KL, Stewart Agras W, Arnow B, et al. The effects of extending cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder among initial treatment nonresponders. Int J Eat Disord. 1997; 21: 347– 52.Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, et al. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine combined with individual cognitive-behaviour therapy in binge eating disorder: a one-year follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 2001; 70: 298– 306.Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Riva G, Bacchetta M, Cesa G, Conti S, Molinari E. Six-month follow-up of in-patient experiential cognitive therapy for binge eating disorders. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003; 6: 251– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, Eldredge K, Marnell M. One-year follow-up of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obese individuals with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997; 65: 343– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine as adjuncts to group behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Obes Res. 2005; 13: 1077– 88.Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Telch CF, Agras WS, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001; 69: 1061– 5.Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, et al. Does interpersonal therapy help patients with binge eating disorder who fail to respond to cognitive-behavioral therapy? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995; 63: 356– 60.Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Evidence Based Practice Center. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Research Triangle Park, NC: Management of Eating Disorders; 2006.Google Scholar

74 Decaluwe V, Braet C. Prevalence of binge-eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003; 27: 404– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Fairburn C, Doll H, Welch S, Hay P, Davies B, O'Connor M. Risk factors for binge eating disorder: a community-based, case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998; 55: 425– 32.Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Mussell MP, Mitchell JE, Weller CL, Raymond NC, Crow SJ, Crosby RD. Onset of binge eating, dieting, obesity, and mood disorders among subjects seeking treatment for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 1995; 17: 395– 401.Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Sullivan H. The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York: W. W. Norton; 1953.Google Scholar

78 Meyer A. Psychobiology: A Science of Man. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1957.Google Scholar

79 Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books; 1982.Google Scholar

80 Wilfley D, MacKenzie KR, Welch RR, Ayres VE, Weissman MM. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Group. New York: Basic Books; 2000.Google Scholar

81 Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York: Basic Books; 1984.Google Scholar

82 Weissman MM, Markowitz J, Klerman GL. Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Behavioral Science Books; 2000.Google Scholar

83 Wilfley D, Stein R, Welch R. Interpersonal psychotherapy. In: Treasure J, Schmidt U, van Furth E, eds. Handbook of Eating Disorders. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2003, pp. 253– 70.Google Scholar

84 Moreau D, Mufson L, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescent depression: description of modification and preliminary application. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991; 30: 642– 51.Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Mufson L, Weissman MM, Moreau D, Garfinkel R. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999; 56: 573– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Weissman MM. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004; 61: 577– 84.Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Rossello J, Bernal G. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal treatments for depression in Puerto Rican adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999; 67: 734– 45.Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Mufson L, Dorta KP, Moreau D, Weissman MM. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2004.Google Scholar

89 Young J, Mufson L. Manual for Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST). New York: Columbia University; 2003.Google Scholar

90 Young JF, Mufson L. Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training: An Indicated Preventive Intervention for Depression. 2007. Unpublished manual.Google Scholar

91 Young JF, Mufson L, Davies M. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training: an indicated preventive intervention for depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006; 47: 1254– 62.Google Scholar

92 Fairburn CG, Jones R, Peveler RC, et al. Three psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa. A comparative trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991; 48: 463– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Wilfley DE, Frank MA, Welch R, Spurrell E, Rounsaville BJ. Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy to a group format (IPT-G) for binge eating disorder: toward a model for adapting empirically supported treatments. Psychotherapy Res. 1998; 8: 379– 91.Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Streigel-Moore RH. Toward an integrated model of risk for binge eating disorder. J Gender Culture Health. 1997; 2: l– 3.Google Scholar

95 Mufson L, Gallagher T, Dorta KP, Young JF. A group adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Am J Psychother. 2004; 58: 220– 37.Crossref, Google Scholar

96 Mclntosh VV, Bulik CM, McKenzie JM, Luty SE, Jordan J. Interpersonal psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2000; 27: 125– 39.Crossref, Google Scholar

97 Mclntosh VV, Jordan J, Carter FA, et al. Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162: 741– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Yanovski SZ. Binge eating disorder and obesity in 2003: could treating an eating disorder have a positive effect on the obesity epidemic? Int J Eat Disord. 2003; 34( Suppl): S117– 20.Crossref, Google Scholar

99 Yanovski SZ. Biological correlates of binge eating. Addict Behav. 1995; 20: 705– 12.Crossref, Google Scholar

100 Yanovski S. Sugar and fat: cravings and aversions. J Nutr. 2003; 133: 835S– 7S.Crossref, Google Scholar

101 Will MJ, Franzblau EB, Kelley AE. The amygdala is critical for opioid-mediated binge eating of fat. Neuroreport. 2004; 15: 1857– 60.Crossref, Google Scholar

102 Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, et al. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet. 2001; 357: 354– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar

103 Wang GJ, Yang J, Volkow ND, et al. Gastric stimulation in obese subjects activates the hippocampus and other regions involved in brain reward circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103: 15641– 5.Crossref, Google Scholar

104 Furmark T, Tillfors M, Marteinsdottir I, et al. Common changes in cerebral blood flow in patients with social phobia treated with citalopram or cognitive-behavioral therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002; 59: 425– 33.Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Paquette V, Levesque J, Mensour B, et al. “Change the mind and you change the brain”: effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the neural correlates of spider phobia. Neuroimage. 2003; 18: 401– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

106 Baxter LR Jr, Schwartz JM, Bergman KS, et al. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992; 49: 681– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

107 Linden DE. How psychotherapy changes the brain—the contribution of functional neuroimaging. Mol Psychiatry. 2006; 11: 528– 38.Crossref, Google Scholar

108 Goldapple K, Segal Z, Garson C, et al. Modulation of cortical-limbic pathways in major depression: treatment-specific effects of cognitive behavior therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004; 61: 34– 41.Crossref, Google Scholar

109 Martin SD, Martin E, Rai SS, Richardson MA, Royall R. Brain blood flow changes in depressed patients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy or venlafaxine hydrochloride: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001; 58: 641– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

110 Brody AL, Saxena S, Stoessel P, et al. Regional brain metabolic changes in patients with major depression treated with either paroxetine or interpersonal therapy: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001; 58: 631– 40.Crossref, Google Scholar

111 Mufson L, Moreau D, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.Google Scholar

112 Striegel-Moore RH, Silberstein LR, Rodin J. Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. Am Psychol. 1986; 41: 246– 63.Crossref, Google Scholar

113 Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. JAMA. 2003; 289: 1813– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

114 Fallon EM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Norman AC, et al. Health-related quality of life in overweight and nonoverweight black and white adolescents. J Pediatr. 2005; 147: 443– 50.Crossref, Google Scholar

115 Tanofsky-Kraff M, Theim KR, Yanovski SZ, et al. Validation of the emotional eating scale adapted for use in children and adolescents (EES-C). Int J Eat Disord. 2007; 40: 232– 40.Crossref, Google Scholar

116 van Strien T. On the relationship between dieting and “obese” and bulimic eating patterns. Int J Eat Disord. 1996; 19: 83– 92.Crossref, Google Scholar

117 Van Strien T, Engels RC, Van Leeuwe J, Snoek HM. The Stice model of overeating: tests in clinical and non-clinical samples. Appetite. 2005; 45: 205– 13.Crossref, Google Scholar

118 Braet C, Van Strien T. Assessment of emotional, externally induced and restrained eating behaviour in nine to twelve-year-old obese and non-obese children. Behav Res Ther. 1997; 35: 863– 73.Crossref, Google Scholar

119 Evans L, Wertheim EH. Intimacy patterns and relationship satisfaction of women with eating problems and the mediating effects of depression, trait anxiety and social anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 1998; 44: 355– 65.Crossref, Google Scholar

120 Tasca GA, Taylor D, Ritchie K, Balfour L. Attachment predicts treatment completion in an eating disorders partial hospital program among women with anorexia nervosa. J Pers Assess. 2004; 83: 201– 12.Crossref, Google Scholar

121 Troisi A, Massaroni P, Cuzzolaro M. Early separation anxiety and adult attachment style in women with eating disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005; 44: 89– 97.Crossref, Google Scholar

122 Humphrey LL. Observed family interactions among subtypes of eating disorders using structural analysis of social behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989; 57: 206– 14.Crossref, Google Scholar

123 Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Spurrell E. Impact of interpersonal and ego-related stress on restrained eaters. Int J Eat Disord. 2000; 27: 411– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

124 Pine DS, Goldstein RB, Wolk S, Weissman MM. The association between childhood depression and adulthood body mass index. Pediatrics. 2001; 107: 1049– 56.Crossref, Google Scholar

125 Goodman E, Whitaker RC. A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002; 110: 497– 504.Crossref, Google Scholar

126 Stice E, Presnell K, Shaw H, Rohde P. Psychological and behavioral risk factors for obesity onset in adolescent girls: a prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005; 73: 195– 202.Crossref, Google Scholar

127 Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Must A. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a prospective community-based study of children followed up into adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006; 160: 285– 91.Crossref, Google Scholar

128 Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Benefits of recruiting participants-with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999; 67: 132– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

129 Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002; 109: 45– 60.Crossref, Google Scholar

130 Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006; 295: 1549– 55.Crossref, Google Scholar

131 Weiss R, Dziura J, Burgert TS, et al. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350: 2362– 74.Crossref, Google Scholar