Insomnia: Prevalence, Impact, Pathogenesis, Differential Diagnosis, and Evaluation

Abstract

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder affecting millions of people as either a primary or comorbid condition. Insomnia has been defined as both a symptom and a disorder, and this distinction may affect its conceptualization from both research and clinical perspectives. Whether insomnia is viewed as a symptom or a disorder, however, it nevertheless has a profound effect on the individual and society. The burden of medical, psychiatric, interpersonal, and societal consequences that can be attributed to insomnia underscores the importance of understanding, diagnosing, and treating the disorder.

INSOMNIA PREVALENCE

The prevalence of insomnia varies depending on the specific case definition. Broadly speaking, insomnia has been viewed as a symptom and as a disorder in its own right. Insomnia has also been defined by subtypes based on frequency; duration (acute versus chronic); and etiology. This picture is further complicated by considerations of insomnia as either a comorbid condition; as a symptom of a larger sleep, medical, or psychiatric disorder; or as a secondary disorder (1). An illustration of this idea is the overlap between insomnia and depression. Do insomnia and depression coexist in an individual as separate disorders? Is insomnia only one symptom in the larger context of depression? Did insomnia secondarily developed as a distinct disorder from a primary depressive disorder?

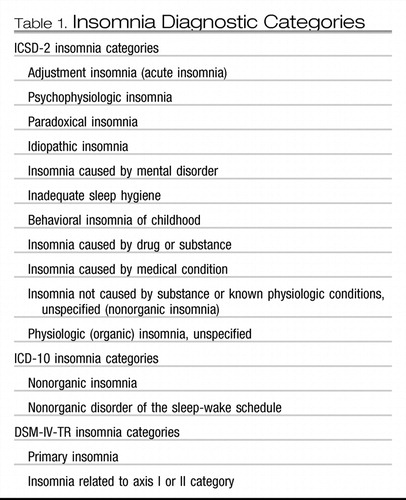

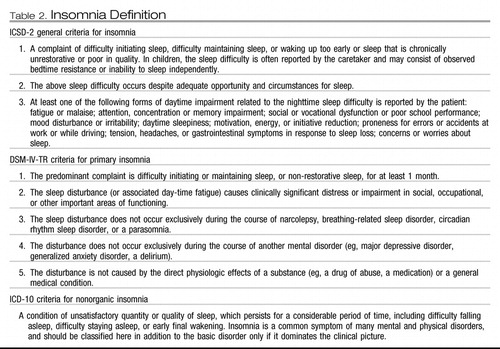

The three main diagnostic manuals, International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2) (2), Diagnostic and Statistic Manual (DSM IV-TR) (3), and International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) (4), vary in their approach to defining insomnia (Table 1). ICSD-2 subdivides insomnia into descriptive, etiologic categories. Examples include adjustment insomnia (insomnia temporally related to an identifiable stressor) and psychophysiologic insomnia (increased arousal and conditioned sleep difficulty) (Table 2) (2). These categories also contain insomnia caused by a mental disorder, substance, or medical condition. The DSM IV-TR separates out primary insomnia (insomnia symptoms associated with distress or daytime impairment) from other “dyssomnias,” such as a breathing-related sleep disorder (3). ICD-10 uses the broadest approach, categorizing insomnia based on underlying pathology: nonorganic insomnia and nonorganic disorder of the sleep-wake schedule (see Table 2) (4). Duration of insomnia (at least 1 month of symptoms) is noted in ICSD-2 and DSM IV-TR; however, frequency of symptoms is broached only in ICD-10.

|

Table 1. Insomnia Diagnostic Categories

|

Table 2. Insomnia Definition

As a result of these differences in insomnia case definitions, estimates of insomnia prevalence have varied widely, from 10% to 40% (5–12). This problem is demonstrated by the findings of a prevalence study from South Korea. When insomnia was defined by frequency (symptoms occurring at least 3 nights per week), 17% of randomly selected subjects from the population qualified for the diagnosis. If the symptom of difficulty maintaining sleep was the defining factor, 11.5% of the sample was affected. Using the more stringent criteria from DSM-IV, however, 5% of the sample qualified for the diagnosis (13). Similar disparities were shown in a prevalence study from France (14). According to a 2005 statement by the National Institutes of Health, insomnia has a prevalence of 10% if the definition necessitates daytime distress or impairment (15). Given all the information available, the prevalence of insomnia symptoms may be estimated at 30% and specific insomnia disorders at 5% to 10% (16).

Several risk factors for insomnia have been identified. Female gender, advanced age, depressed mood, snoring, low levels of physical activity, comorbid medical conditions, nocturnal micturation, regular hypnotic use, onset of menses, previous insomnia complaints, and high level of perceived stress have all been implicated as risk factors; the first three factors in particular (female gender, advanced age, and depressed mood) are consistent risk factors (7, 17–22).

Precipitants of insomnia have also been studied. Bastien and colleagues (23) examined precipitating factors of insomnia and found that family, work or school, and health events proved to be the most common precipitants (23). Another study of psychosocial stressors in Japan demonstrated that employees with greater intragroup conflict and job dissatisfaction had greater risk for insomnia (24).

Knowledge of both risk factors and possible precipitants of insomnia can help to guide the evaluation and treatment of insomnia. Questions about psychosocial stressors at home and at work in high-risk individuals, such as those experiencing depression or who are female or elderly, can help to shape and direct patient care.

INSOMNIA IMPACT

Insomnia and psychiatric conditions

An estimated 40% of individuals with insomnia have a comorbid psychiatric condition (7, 25). In a review of epidemiologic studies, Taylor and colleagues (26) found that insomnia predicted depression, anxiety, substance abuse or dependence, and suicide (26). The correlation between insomnia and later development of depression within 1 to 3 years is particularly strong (27). Johnson and colleagues (28) found that in a community sample of adolescents, in 69% of cases insomnia preceded comorbid depression, whereas an anxiety disorder preceded insomnia 73% of the time (28). In a large group of subjects aged 15 to 100 years, insomnia either appeared before (>40%) or at the same time (>22%) as mood disorders. This study also found that insomnia appeared at the same time as (>38%) or after (34%) anxiety disorders (29).

As further evidence of morbidity, individuals with insomnia complaints in the last year but without any previous psychiatric history were shown to have an increased risk of first-onset major depression, panic disorder, and alcohol abuse the following year when compared with controls (30). Furthermore, adolescents who completed suicide were found to have higher rates of insomnia in the week preceding death than community-control adolescents (31, 32).

Taken as a whole, these findings underscore the impact of insomnia on the individual while suggesting a possible relationship between insomnia and psychiatric disorders. The nature of this relationship has yet to be established. Insomnia could be an early symptom, part of a prodrome, of a depressive or anxiety disorder. Similarly, insomnia might also exist as a separate, comorbid disorder that either gave rise to or developed from a psychiatric condition. In either case the need to address insomnia and psychiatric disorders together remains important.

Insomnia and medical conditions

Associations between insomnia and a variety of medical conditions have also been established. Taylor and colleagues (33) found that in a community-based sample chronic insomniacs reported more heart disease, hypertension, chronic pain, and increased gastrointestinal, neurologic, urinary, and breathing difficulties. The converse was also shown to be true, in which subjects with hypertension, chronic pain, breathing, gastrointestinal, and urinary problems complained of insomnia more often than noninsomniacs (33). Others have also found increased odds ratios for insomnia in a variety of medical conditions, ranging from congestive heart failure to hip impairment (34).

Ancoli-Israel (35) emphasized the different ways that insomnia and chronic medical conditions may relate to each other: sleep complaints may function as a symptom of a disorder, such as congestive heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration gastroesophageal reflux disease and increased arousals. In other cases, insomnia may be a component of the etiology of a disorder, such as diabetes mellitus (35).

The connection between cardiovascular disease and insomnia bears specific attention. After adjusting for age and coronary risk factors, a risk ratio of 1.5 to 3.9 between difficulty falling asleep and coronary heart disease has been demonstrated (36). Men who experienced difficulty falling asleep were also shown to have a threefold risk of death secondary to coronary heart disease (37).

The relationship between chronic pain and insomnia is also of particular clinical relevance. In one study, more than 40% of insomniacs reported having at least one chronic painful physical condition. Moreover, chronic pain was in turn associated with shorter sleep duration and decreased ability to resume sleep following arousal (38). Tang and colleagues (39) found that 53% of chronic pain patients had scores suggestive on the Insomnia Severity Index of clinical insomnia versus 3% of subjects without pain (39).

Socioeconomic impact of insomnia

In addition to psychiatric and medical comorbidities, insomnia is associated with substantial personal and societal consequences. One study that examined the effect of insomnia on primary care patients found insomniacs had double the number of days with restricted activity because of illness (11). Another study showed that more insomniacs rated their quality of life as poor (22%) compared with subjects without any sleep complaints (3%) (32). Insomnia has also been shown to have a detrimental effect on health-related quality of life to the same degree as chronic disorders, such as depression and congestive heart failure (40). When the economic costs that encompass health care use, workplace effects of absenteeism, accidents, and increased alcohol consumption secondary to insomnia were considered, the annual cost was estimated to be between $35 to $107 billion a year (41, 42). Insomnia has not been found to be associated with increased risk of death (43).

Health care use, as defined by increased office visits and rates of hospitalization, is consistently higher in insomniacs than in subjects without sleep complaints (44, 45). The direct costs incurred through inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, and emergency room usage are greater in insomniacs regardless of age (46). An evaluation of the direct health care costs of insomnia in 1995 placed estimates at $13.9 billion in the United States and $2.1 billion in France (47, 48).

Function in the workplace is also negatively affected. Insomniacs miss work twice as often as good sleepers, with absenteeism particularly prominent in men and blue-collar workers (49). The extra cost of work absenteeism secondary to insomnia, through decreased productivity and salary replacement, is then brought to bear on employers (50).

INSOMNIA PATHOGENESIS

Insomnia is often believed to arise from a state of hyperarousal. In the physiologic hyperarousal model, an elevated level of alertness throughout the day and night makes it difficult to sleep. In support of this theory, insomniacs have been found to have an increased whole body metabolic rate when compared with normal sleepers (51, 52). They also score higher than normal sleepers on a Hyperarousal Scale, and even during the day when complaining of fatigue, insomniacs still take a longer time to fall asleep (53, 54).

On functional neuroimaging, insomniacs show increased cerebral glucose metabolism during sleep and wake states (55). On electroencephalography, insomniacs demonstrate increased beta activity and lower delta activity (56, 57). From an endocrine perspective, insomniacs, like patients with major depressive disorder, demonstrate corticotropin-releasing factor hyperactivity, suggesting a role for hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction (58).

INSOMNIA EVALUATION

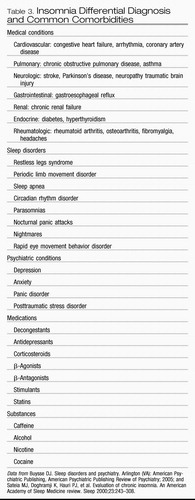

The cornerstone of the insomnia evaluation is a detailed history obtained during the patient interview. Although the approach to the interview may vary depending on the practitioner, key points should be covered to ensure a thorough evaluation. Additional assessment tools, such as the sleep-wake diary, actigraphy, and in specific cases polysomnography, can supplement the information obtained in the interview. A list of diagnoses and comorbid conditions to consider during the insomnia evaluation can be found in Table 3.

|

Table 3. Insomnia Differential Diagnosis and Common Comorbidities

Patient interview

Detailed information about the nature of the complaint is necessary, such as if insomnia is related to sleep onset, sleep maintenance, early morning awakening, nonrestorative sleep quality, or a combination of these problems. Information obtained here may help to guide the diagnosis, such as a sleep-onset complaint resulting from restless legs syndrome as opposed to an early morning awakening presenting as part of a depressive disorder. Additional information about the onset, course and duration, current presentation, frequency, severity, and precipitating or alleviating factors also helps to define the problem. In particular, a life-long course with an onset in the absence of medical and psychiatric comorbidities may suggest a primary insomnia as opposed to a secondary insomnia that develops in late adulthood in the context of chronic pain.

The sleep schedule, including bedtime, sleep latency, number and length of nighttime awakenings, sleep reinitiation time, wake time, time spent in bed, and total sleep time, should be reviewed. A patient's preferred bedtime may not coincide with actual bedtime, as in a circadian rhythm disorder. Similarly, nighttime awakenings caused by nightmares from posttraumatic stress disorder as opposed to awakenings from nocturia caused by prostate enlargement suggest different disorders.

The daytime routine with a review of work schedule, eating and exercise times, and duration and timing of naps is also important. Eating and exercise times that occur in close temporal relation to bedtimes may inhibit the patient's ability to fall asleep. Moreover, naps of long duration that occur in the late afternoon or evening may have a similar negative effect on sleep latency and continuity.

A discussion of daytime functioning and associated symptoms includes daytime sleepiness; fatigue; difficulty with memory and concentration; depression; anxiety; irritability; impairment at work, school, or home; and overall quality of life. A report of daytime impairment and patient distress may underscore the severity of symptoms, and highlight the need aggressively to treat insomnia. In this area, collateral report from family, teachers, or coworkers may prove helpful if the patient is unaware of the extent of his or her symptoms.

Safety issues, such as the negative effect on driving and work performance in potentially hazardous areas, should be broached and may provide an opportunity for patient education.

Sleep conditions and routines should be discussed, such as the conditions of the room used for sleep (eg, effect of light, temperature, and noise); use of television, computer, or radio both in the prebedtime routine and during periods of nighttime awakenings; the effect of anxiety during sleep latency and sleep reinitiation periods; and the presence of clock-watching before and during sleep times. Too much noise or light exposure in the sleeping room may inhibit sleep initiation. Similarly, clock-watching with each nighttime awakening may only further heighten an already raised level of anxiety. Specific difficulty falling asleep at home but not while out of town may suggest insomnia related to the bedroom environment.

Previous treatments tried and their effects and side effects should be discussed. Treatments may include over-the-counter, homeopathic, herbal, or prescription medications and behavioral therapies. In addition to providing information on potential treatments that may not have yet been offered to the patient, information obtained in this area may provide a sense of the kind of treatment for which the patient is looking.

Symptoms of other sleep disorders that could be affecting the complaint include such conditions as restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, sleep apnea, and sleep phase syndromes. These should be considered as possible contributors to insomnia.

One should review comorbid medical conditions that could play a role in the presentation. General categories to consider include cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurologic, gastrointestinal, renal, endocrine, and rheumatologic.

Review of underlying psychiatric conditions and psychosocial stressors should be included. Eliciting symptoms of depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, panic (including nocturnal panic attacks), and psychosis can help to clarify the diagnostic picture while emphasizing the need to obtain or continue psychiatric care.

A review of substance use, including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine, should cover amount, frequency, and time of day the substance is used because all of these substances may contribute to an insomnia complaint. Patient education about the effects of nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine on sleep should also be undertaken if it seems that substance use has a negative effect on sleep quality.

Finally, one should undertake a review of family history of sleep, medical, and psychiatric disorders.

Physical and mental status examination

The physical examination may reveal signs consistent with sleep apnea (obesity, enlarged neck circumference, crowded oropharynx) and thyroid, cardiac, respiratory, and neurologic disorders.

The mental status examination may yield information about the patient's mood, affect, level of alertness, and ability to attend.

Collateral sources interview

Interview the patient's bed partner or family members, if possible, to elicit symptoms of which the patient may be unaware. This part of the evaluation may also help to corroborate and expand on the patient's original description. Revelation about respiratory symptoms (snoring, apneas, or gasping) could suggest a sleep-disordered breathing etiology, whereas report of repeated limb movements may move the diagnosis toward restless legs syndrome or periodic limb movement disorder.

OBJECTIVE DATA

Actigraphy

Actigraphy helps to characterize rest-activity patterns and may have some use as an objective measure when used in conjunction with a sleep-wake dairy and formal interview. For insomniacs actigraphy can provide information about circadian rhythms and sleep patterns (59). Compared with polysomnography, however, actigraphy in insomniacs has had variable results: it has been found to overestimate and underestimate total sleep time (60–62). Another study found that actigraphy was well validated by polysomnography with respect to number of awakenings, wake time after sleep onset, total sleep time, and sleep efficiency (63). When using actigraphy, increasing the duration of recording to more than 7 days may improve the reliability of sleep time estimates (64).

Polysomnography

Polysomnography is not routinely used in the evaluation of insomnia; the onus of the diagnosis lies instead on the patient interview. According to 2003 practice parameters established by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, specific cases may apply when polysomnography is warranted. These cases include suspicion of sleep-related breathing disorders or periodic limb movement disorders, uncertain initial diagnosis, treatment failure, and arousals leading to violent behavior (65).

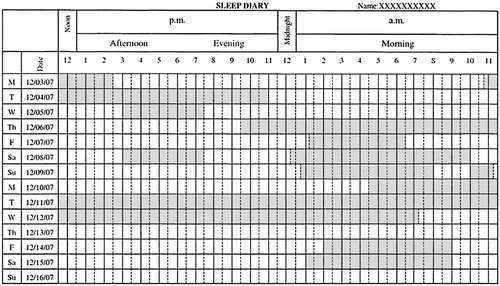

Sleep diaries

Sleep diaries recorded over 1 to 2 weeks can help track a patient's sleep-wake patterns. Information including actual sleep-wake times, duration of time in bed, and day-to-day variability in sleep-wake times can be gathered from the diaries (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Sleep Diary.

SUMMARY

Insomnia is thought to result from a state of hyperarousal. As a result of this elevated state of alertness, sleep may prove difficult. Formulating a clinical definition of insomnia has proved a challenge. Nevertheless, some enduring characteristics of insomnia include difficulty with sleep initiation or maintenance, early morning awakening, and nonrestorative sleep in the setting of daytime impairment or distress in the setting of adequate sleep opportunity. With these characteristics in mind the prevalence of insomnia is thought to be approximately 10%.

The evaluation of insomnia emphasizes the interview, during which information about the specific complaint, comorbid sleep, medical or psychiatric conditions, family histories, medication, and substance use may be gathered. Additional information from collateral sources, sleep diaries, actigraphy, and polysomnography may also prove useful.

Insomnia is a disorder that has far-reaching effects: medical, psychiatric, personal, and societal consequences have all been linked with insomnia. The cost of insomnia can be measured not just in dollars, but also in impaired quality of life from comorbid conditions and impaired interpersonal relationships.

[1] Harvey AG. Insomnia: symptom or diagnosis? Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21: 1037– 59.Google Scholar

[2] American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International classification of sleep disorders, second edition (ICSD-2): diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd edition. Westchester (IL): American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.Google Scholar

[3] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). 4th edition. Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.Google Scholar

[4] World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1992.Google Scholar

[5] Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. I. Sleep 1999; 22( Suppl 2): S347– 53.Google Scholar

[6] Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, et al. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136: 1257– 62.Crossref, Google Scholar

[7] Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: an opportunity for prevention? JAMA 1989; 262: 1479– 84.Google Scholar

[8] Kuppermann M, Lubeck DP, Mazonson PD, et al. Sleep problems and their correlates in a working population. J Gen Intern Med 1995; 10: 25– 32.Crossref, Google Scholar

[9] Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. Insomnia and its treatment: prevalence and correlates. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42: 225– 32.Crossref, Google Scholar

[10] Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev 2002; 6: 97– 111.Crossref, Google Scholar

[11] Simon GE, Von Korff M. Prevalence, burden, and treatment of insomnia in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 1417– 23.Crossref, Google Scholar

[12] Ustun TB, Privett M, Lecrubier Y, et al. Form, frequency and burden of sleep problems in general health care: a report from the WHO collaborative study on psychological problems in general health care. Eur Psychiatry 1996; 11: S5– 10.Crossref, Google Scholar

[13] Ohayon MM, Hong SC. Prevalence of insomnia and associated factors in South Korea. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53: 593– 600.Crossref, Google Scholar

[14] Leger D, Guilleminault C, Dreyfus IP, et al. Prevalence of insomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. J Sleep Res 2000; 9: 35– 42.Crossref, Google Scholar

[15] National Institutes of Health. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults. Bethesda (MD): 2005.Google Scholar

[16] Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med 2007; 3: S7– 10.Google Scholar

[17] Johnson EO, Roth T, Schultz L, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-IV insomnia in adolescence: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics 2006b; 117: E247– 56.Crossref, Google Scholar

[18] Klink ME, Quan SF, Kaltenborn WT, et al. Risk factors associated with complaints of insomnia in a general adult population. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152: 1634– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar

[19] Morgan K. Daytime activity and risk factors for late-life insomnia. J Sleep Res 2003; 12: 231– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

[20] Morgan K, Clarke D. Risk factors for late-life insomnia in a representative general practice sample. Br J Gen Pract 1997; 47: 166– 9.Google Scholar

[21] Murata C, Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi K, et al. Psychological factors and insomnia among male civil servants in Japan. Sleep Med 2007; 8: 209– 14.Crossref, Google Scholar

[22] Su TP, Huang SR, Chou P. Prevalence and risk factors of insomnia in community-dwelling Chinese elderly: a Taiwanese urban area survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2004; 38: 706– 13.Crossref, Google Scholar

[23] Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Precipitating factors of insomnia. Behav Sleep Med 2004; 2: 50– 62.Crossref, Google Scholar

[24] Nakata A, Haratani T, Takahashi M, et al. Job stress, social support, and prevalence of insomnia in a population of Japanese daytime workers. Soc Sci Med 2004; 59: 1719– 30.Crossref, Google Scholar

[25] McCall WV. A psychiatric perspective on insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62( Suppl 10): 27– 32.Google Scholar

[26] Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH. Insomnia as a health risk factor. Behav Sleep Med 2003; 1: 227– 47.Crossref, Google Scholar

[27] Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord 2003; 76: 255– 9.Google Scholar

[28] Johnson EO, Roth T, Breslau N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: exploration of the direction of risk. J Psychiatr Res 2006a; 40: 700– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

[29] Ohayon MM, Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res 2003; 37: 9– 15.Crossref, Google Scholar

[30] Weissman MM, Greenwald S, Nino-Murcia G, et al. The morbidity of insomnia uncomplicated by psychiatric disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1997; 19: 245– 50.Crossref, Google Scholar

[31] Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008; 76: 84– 91.Crossref, Google Scholar

[32] Hajak G, SINE Study Group, Study of Insomnia in Europe. Epidemiology of severe insomnia and its consequences in Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 251: 49– 56.Crossref, Google Scholar

[33] Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, et al. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep 2007; 30: 213– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

[34] Katz DA, McHorney CA. Clinical correlates of insomnia in patients with chronic illness. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 1099– 107.Crossref, Google Scholar

[35] Ancoli-Israel S. The impact and prevalence of chronic insomnia and other sleep disturbances associated with chronic illness. Am J Manag Care 2006; 12: S221– 9.Google Scholar

[36] Schwartz S, McDowell AW, Cole SR, et al. Insomnia and heart disease: a review of epidemiologic studies. J Psychosom Res 1999; 47: 313– 33.Crossref, Google Scholar

[37] Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Sleep complaints predict coronary artery disease mortality in males: a 12-year follow-up study of middle-aged Swedish population. J Intern Med 2002; 251: 207– 16.Crossref, Google Scholar

[38] Ohayon MM. Relationship between chronic painful physical condition and insomnia. J Psychiatr Res 2005; 39: 151– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

[39] Tang NK, Wright KJ, Salkovskis PM. Prevalence and correlates of clinical insomnia co-occurring with chronic back pain. J Sleep Res 2007; 16: 85– 95.Crossref, Google Scholar

[40] Katz DA, McHorney CA. The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. J Fam Pract 2002; 51: 229– 35.Google Scholar

[41] Chilcott LA, Shapiro CM. The socioeconomic impact of insomnia. Pharmacoeconomics 1996; 10: 1– 14.Crossref, Google Scholar

[42] Stoller MK. Economic effects of insomnia [review]. Clin Ther 1994; 16: 873– 97 [discussion: 854].Google Scholar

[43] Phillips B, Mannino DM. Does insomnia kill? Sleep 2005; 28: 965– 71.Google Scholar

[44] Leger D, Guilleminault C, Bader G, et al. Medical and socio-professional impact of insomnia. Sleep 2002; 25: 625– 9.Google Scholar

[45] Novak M, Mucsi I, Shapiro CM, et al. Increased utilization of health services by insomniacs: an epidemiological perspective. J Psychosom Res 2004; 56: 527– 36.Crossref, Google Scholar

[46] Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Walsh JK. The direct and indirect costs of untreated insomnia in adults in the United States. Sleep 2007; 30: 263– 73.Crossref, Google Scholar

[47] Leger D, Levy E, Paillard M. The direct costs of insomnia in France. Sleep 1999; 22: S394– 401.Google Scholar

[48] Walsh JK, Engelhardt CL. The direct economic costs of insomnia in the United States for 1995. Sleep 1999; 22: S386– 93.Google Scholar

[49] Leger D, Massuel MA, Metlaine A. Professional correlates of insomnia. Sleep 2006; 29: 171– 8.Google Scholar

[50] Godet-Cayre V, Pelletier-Fleury N, Le Vaillant M, et al. Insomnia and absenteeism at work. Who pays the cost? Sleep 2006; 29: 179– 84.Google Scholar

[51] Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Hyperarousal and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 1997; 1: 97– 108.Crossref, Google Scholar

[52] Stepanski E, Zorick F, Roehrs T, et al. Daytime alertness in patients with chronic insomnia compared with asymptomatic control subjects. Sleep 1988; 11: 54– 60.Crossref, Google Scholar

[53] Bonnet MH, Arand DL. 24-hour metabolic rate in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Sleep 1995; 18: 581– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

[54] Pavlova M, Berg O, Gleason R, et al. Self-reported hyperarousal traits among insomnia patients. J Psychosom Res 2001; 51: 435– 41.Crossref, Google Scholar

[55] Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, et al. Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 2126– 31.Crossref, Google Scholar

[56] Krystal AD, Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, et al. NREM sleep EEG frequency spectral correlates of sleep complaints in primary insomnia subtypes. Sleep 2002; 25: 630– 40.Google Scholar

[57] Perlis ML, Smith MT, Andrews PJ, et al. Beta/Gamma EEG activity in patients with primary and secondary insomnia and good sleeper controls. Sleep 2001; 24: 110– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar

[58] Roth T, Roehrs T, Pies R. Insomnia: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Sleep Med Rev 2007; 11: 71– 9.Crossref, Google Scholar

[59] Morgenthaler T, Alessi C, Friedman L, et al. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders: an update for 2007. Sleep 2007; 30: 519– 29.Crossref, Google Scholar

[60] Sadeh A, Acebo C. The role of actigraphy in sleep medicine. Sleep Med Rev 2002; 6: 113– 24.Crossref, Google Scholar

[61] Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Havik OE, et al. A comparison of actigraphy and polysomnography in older adults treated for chronic primary insomnia. Sleep 2006; 29: 1353– 8.Crossref, Google Scholar

[62] Vallieres A, Morin CM. Actigraphy in the assessment of insomnia. Sleep 2003; 26: 902– 6.Crossref, Google Scholar

[63] Lichstein KL, Stone KC, Donaldson J, et al. Actigraphy validation with insomnia. Sleep 2006; 29: 232– 9.Google Scholar

[64] Van Someren EJ. Improving actigraphic sleep estimates in insomnia and dementia: how many nights? J Sleep Res 2007; 16: 269– 75.Google Scholar

[65] Littner M, Hirshkowitz M, Kramer M, et al. Practice parameters for using polysomnography to evaluate insomnia. Sleep 2003; 26: 754– 7.Crossref, Google Scholar