Medications and Sexual Function and Dysfunction

The relationship between pharmacological agents (including herbal preparations and medications) and sexual functioning has been explored since the antiquities. For centuries, the main focus was on preparations or foods that could enhance one's sexual functioning or desire—that is, on aphrodisiacs (a word derived from the name of the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite). Some of the aphrodisiacs may contain chemicals that potentially influence sexual desire or other aspects of sexual functioning. Some of them, such as rhinoceros horn or oysters, were considered to be aphrodisiacs mainly for their symbolic notion.

The human search for aphrodisiacs has continued to the present time. Chocolate has sometimes been promoted as a food that could enhance one's sexual functioning, and many so-called natural preparations have been touted the same way. Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors and testosterone are not considered aphrodisiacs in a strict sense, yet their advertisements frequently border on promoting them as aphrodisiacs. The everlasting interest in pharmacological aids for sexual functioning has been demonstrated numerous times by the huge media attention to even the smallest findings of possible improvement or enhancement of sexual functioning via pharmacological agents.

During the last several decades, the complicated relationship between pharmaceutical agents and sexual functioning has also become a focus. The impairment of sexual functioning has been associated with various pharmacological agents, both psychotropic and nonpsychotropic. Numerous medications have been reported to be associated with impaired sexual functioning, affecting either the entire sexual response cycle or (less frequently) one phase of this cycle (although the phases are interconnected and cannot be clearly and unequivocally separated). Basically, the field of sexual pharmacology has gradually developed over the last few decades (see the books on sexual pharmacology by Crenshaw and Goldberg [1996] and Segraves and Balon [2003]). Impaired sexual functioning due to medications not only can significantly impact the patient's quality of life but also can lead to nonadherence to the medication regimen.

In this chapter, I focus on impaired sexual functioning due to various medications and its possible management, with the main focus on a prototypical group of medications associated with sexual dysfunction—antidepressants. In addition, I briefly mention pharmacological agents used for the treatment of various sexual dysfunctions and disorders, most of which are discussed in more detail in other chapters, and also some substances that may not help as much as previously believed or do not help at all. Importantly, this chapter serves as an overview and offers clinically oriented guidance for the assessment and management of sexual dysfunction associated with medications, not an exhaustive review of sexual pharmacology.

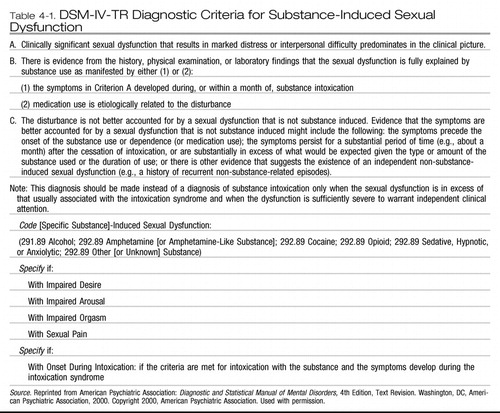

DEFINITION OF AND CRITERIA FOR SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION ASSOCIATED WITH MEDICATIONS

As noted in DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000),

A substance-induced sexual dysfunction due to a prescribed treatment for a mental disorder or general medical condition must have its onset while the person is receiving the medication (e.g., antihypertensive medication). Once the treatment is discontinued, the sexual dysfunction will remit within days to several weeks (depending on the half-life of the substance). If the sexual dysfunction persists, other causes for the dysfunction should be considered. (p. 564)

|

Table 4-1. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Substance-Induced Sexual Dysfunction

Some of the DSM-IV-TR criteria may not be perfectly clear (e.g., the etiological relationship, like many etiological relationships in psychiatry, is usually presumed) or may be a bit controversial (for recent case reports of persistent sexual dysfunction, see Bolton et al. 2006 and Csoka and Shipko 2006). However, these criteria succinctly summarize the issue in defining medication-induced sexual dysfunction.

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Depression is frequently associated with sexual dysfunction (e.g., Baldwin 1996), especially low sexual desire, but also other impairments, such as erectile dysfunction. The impairment of sexual functioning does not, however, mean that depressed and anxious patients consider sexual functioning unimportant, that they do not wish to have a good sexual life, or that they are contented to have their sexual functioning even more impaired due to medications. Therefore, the management of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressants has emerged as an important clinical area.

Antidepressants have been the most studied group of medications with regard to sexual dysfunction, at least in psychiatry. Case reports and/or case series of sexual dysfunctions associated with antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs]) appeared not very long after the introduction of these agents (e.g., Beaumont 1977). However, like many other side effects, sexual dysfunctions associated with antidepressants have not been systematically studied for decades. Paradoxically, the development of newer, better tolerated antidepressants, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and their use in treating less severe conditions probably led to an increased awareness and focus on the impairment of sexual functioning associated with antidepressants.

Since the early 1990s, numerous reports, studies, and review articles have addressed sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressants. Nobody questions the existence of sexual dysfunction associated with this group of medications. As Montgomery et al. (2002) pointed out,

Sexual dysfunction is widespread in the healthy non-depressed population and is a recognized symptom of depression and/or anxiety disorders (some would add also others, such as eating disorders). Sexual dysfunction has been reported with all classes of antidepressants (MAOIs, TCAs, SSRIs, SNRIs [serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors], and newer antidepressants) in patients with depression and various anxiety disorders. Numerous studies have been published, but only one used a validated sexual function rating scale and most lacked either a baseline or a placebo control or both. (p. 119)

The estimates of incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressants are usually between 30% and 40% (some would claim up to 70%), but the numbers vary widely, from as low as 10% to as high as 90% with some medications (Monteiro et al. 1987). As pointed out by many researchers (e.g., Segraves and Balon 2003), the character and frequency of sexual dysfunction associated with different groups of antidepressants may vary somewhat. For instance, compared with other antidepressants, predominantly serotonergic antidepressants such as SSRIs and clomipramine seem to be more frequently associated with delayed orgasm or anorgasmia, and TCAs seem to be more frequently associated with erectile dysfunction. The reasons for the wide range of estimates include the imprecise definition of sexual dysfunction, the lack of using standard instruments, and the discrepancy between estimates obtained via self-reporting and via active questioning. For instance, in a study by Landen et al. (2005), more patients (41%) reported sexual dysfunction in response to direct questioning than through spontaneous reporting (6%).

The etiology of sexual dysfunction during antidepressant therapy is complicated and not well understood. The impact of antidepressants on various neurotransmitter systems, such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin systems, certainly plays a major role. Dopamine influences motivated sexual behavior, desire, and the ability to become involved in sexual activity (Clayton and Montejo 2006); norepinephrine stimulates sexual arousal and vasocongestion; and serotonin system activation may suspend vasocongestion, turning off arousal. Serotonin may also diminish nitric oxide function and decrease genital sensation (Clayton and Montejo 2006). As suggested in the study by Safarinejad (2008), some antidepressants (SSRIs) may decrease the levels of hormones involved in the regulation of sexual functioning, such as testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and others.

The complicated interaction of psychotropic medications, neurotransmitters, and the peripheral and central nervous systems was summarized by Segraves (1989). However, as Clayton and Montejo (2006) pointed out, many more potential causes of sexual dysfunction exist during antidepressant therapy, including, besides the mentioned ones, psychiatric illness; medical illness; interpersonal conflicts; substance abuse; developmental issues; sexual trauma; concerns about sexually transmitted diseases; psychological issues (self-esteem); cultural, religious, and environmental issues; pregnancy and childbearing issues; life cycle issues; neurological insult; and partner and/or sexual-specific issues. As pointed out in Chapter 2, “Clinical Evaluation of Sexual Dysfunctions,” all these factors should be considered during the baseline evaluation of any sexual dysfunction, including sexual dysfunction associated with medications.

OTHER PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS

Antipsychotics

Sexual dysfunction has been linked to typical or traditional antipsychotics since the late 1960s (Kelly and Conley 2004). Kotin and Wilbert (1976) reported that among patients treated with thioridazine, 60% experienced sexual impairment, 44% had troubles with ejaculation, and 35% had difficulty maintaining an erection. The incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antipsychotics has been estimated to be around 50% among patients with schizophrenia treated with these medications. However, some of the more recent studies reported rates as high as 80%–90% (Kelly and Conley 2004).

Determining the incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antipsychotics is even more complicated than determining the incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressants. Although many newer antipsychotics have recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for wider indications, such as treatment of mood and anxiety disorders, most of the incidence reports are from samples of patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics. Patients with schizophrenia are typically less engaged in sexual activities in general and have lower libido. These patients are also fairly unreliable when questioned about their sexual functioning, especially during a psychotic episode. In addition, psychiatrists may not feel comfortable speaking to these patients about their sexual problems or may not feel that this is an important area to address. Another problem is the lack of a reliable and valid instrument for estimating sexual dysfunction in this population. Additionally, most of the data on sexual dysfunction associated with antipsychotics has been obtained from studies and reports involving typical antipsychotics, yet these medications have been prescribed less frequently than the atypical antipsychotics in recent years. The incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with the newer antipsychotics is usually cited as fairly low, 10%–30%, and in some cases even in the single digits.

Sexual problems described as associated with antipsychotics (mostly the typical ones) include decreased libido, impaired erection, priapism, retrograde ejaculation, painful ejaculation, delayed orgasm, amenorrhea, and other disturbances of the menstrual cycle.

The mechanism of sexual dysfunction associated with antipsychotics is complex. Prolactin elevation has frequently been mentioned as the main culprit. Knegtering et al. (2008) reported that around 40% of emerging sexual side effects in patients with schizophrenia in their study were attributable to the prolactin-raising properties of antipsychotics. However, as Kelly and Conley (2004) pointed out, other factors, such as cholinergic antagonism, alpha-adrenergic blockade, serotonin activity, extrapyramidal side effects, tardive dyskinesia, and nonspecific effects such as sedation and weight gain (histamine receptors), may also play a significant role.

Mood stabilizers

Evidence of sexual dysfunction associated with mood stabilizers is scarce. This scarcity of data has several possible explanations. First, with many antipsychotics being approved for various phases of bipolar disorder and claims of their mood-stabilizing properties, it is less clear what a “mood stabilizer” is and what drugs should be classified as mood stabilizers. Second, the incidence of sexual dysfunction with mood stabilizers seems to be low. Third, the available incidence data suffer from the fact that they were obtained mostly from case reports and series or from studies with poor methodology. Fourth, the estimate of sexual dysfunction associated with mood stabilizers is clouded by the changes of libido that typically occur during the course of bipolar disorder. During the manic phase, many patients report hypersexuality, but a few report diminished libido. As already mentioned, depression can be associated with diminished libido, erectile dysfunction, and other problems.

Unless combined with other medications, lithium appears to have limited adverse sexual side effects (Labbate 2008). Most of the data on sexual dysfunction associated with anticonvulsants that are used as mood stabilizers (e.g., carbamazepine, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, valproic acid) comes from the epilepsy literature; the data on these drugs from bipolar disorder literature are either nonexistent or very limited. Sexual dysfunction associated with lamotrigine and valproic acid is considered to be rare. Carbamazepine induces metabolism of androgen and impacts other hormones, and thus is considered more prone to be associated with sexual dysfunction. Again, however, the evidence of this association is weak.

The mechanism of sexual dysfunction associated with mood stabilizers is probably multifactorial. These medications may combine effects on various neurotransmitters in the peripheral and central nervous systems, on metabolism of various hormones, and on sex hormone-binding globulin.

Antianxiety medications

Medications usually used for treatment of anxiety and anxiety disorders include benzodiazepines, buspirone, various antidepressants, and more recently antipsychotics. All benzodiazepines have occasionally been reported as being associated with sexual dysfunction. However, the evidence is mostly anecdotal, and good studies are nonexistent. Decreased libido and impaired arousal and orgasm have been reported with benzodiazepines (Labbate 2008). Most benzodiazepines seem to have a dose-response relationship between the drug dose and sexual inhibition (Segraves and Balon 2003). Whether an association exists between benzodiazepines and sexual disinhibition is unclear. The estimate of frequency and the evaluation of sexual dysfunction associated with benzodiazepines are confounded by the association of sexual dysfunction with anxiety and anxiety disorders (Zemishlany and Weizman 2008). The mechanism of sexual dysfunction associated with benzodiazepines is not known but may involve gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors in the midbrain central gray or ventral tegmental area.

Buspirone is an anxiolytic that exerts its antianxiety effect through serotonin type 1A (5-HT1A) presynaptic and postsynaptic receptors. It does not seem to have any effect on sexual functioning and has actually been used to reverse sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs (Norden 1994).

Stimulants and other medications used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Stimulants, such as various formulas of methylphenidate or amphetamine and its salts, are usually not associated with sexual dysfunction and are occasionally used for alleviation of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressants. Treatment-emergent decreased libido and erectile dysfunction were described in one study with atomoxetine, a nonstimulant medication used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Adler et al. 2006); in this study, the incidence of both these sexual side effects was low.

Other medications used to treat mental disorders

Sexual dysfunction has not been reported to be associated with modafinil. The incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with guanfacine is low.

NONPSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS

Although the association between sexual functioning and psychotropic medications has received relatively more attention in the scientific and lay literature, nonpsychotropic medications are also frequently associated with impairment of sexual functioning. Frequently, sexual dysfunction is also associated with the physical illness treated by these medications, and the primary or secondary contributing roles of medications to sexual dysfunction are not fully appreciated. The focus in this chapter is on medications used for a longer period of time or chronically, rather than on agents used occasionally or for a brief period of time, such as antibiotics. For a full review of evidence regarding the latter medications, the interested reader is referred to books on sexual pharmacology by Crenshaw and Goldberg (1996) and Segraves and Balon (2003).

The following groups of medications are frequently mentioned as being associated with sexual dysfunction:

| •. | Cardiovascular medications (e.g., antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, lipid-lowering medications, vasodilators, combination agents): These medications are most frequently associated with erectile dysfunction. However, decreased libido in both genders, impaired lubrication in women, and ejaculatory or orgasmic delay or inhibition may also occur. | ||||

| •. | Chemotherapeutic (antineoplastic, cytotoxic) agents (e.g., antibiotics, anti-metabolites, alkylating agents, hormones, immunomodulators, plant agents): These medications are frequently very toxic, and their impact on sexual organs and sexual functioning is not fully appreciated. Decreased libido is a frequent complication of chemotherapy, but impaired arousal (frequently due to vaginal dryness), dyspareunia, and difficulties in reaching orgasm also occur. Evaluation of sexual functioning associated with chemotherapeutic agents is complicated by other factors, such as nerve damage by these agents, nerve and vascular damage by possible radiation, potential surgical damage (e.g., during prostate surgery), and associated medical symptoms (nausea) and psychological symptoms (anxiety, depression), as well as treatment of these symptoms with SSRIs. | ||||

| •. | Gastrointestinal agents (e.g., antacids, antidiarrheals, antiemetics, antispasmodics, histamine receptor agonists, proton pump inhibitors): Physicians should remember that patients with severe nausea or frequent diarrhea are probably not involved in sexual activity, and therefore their sexual dysfunction may not be due to the gastrointestinal agents. The full scope and character of sexual dysfunction associated with these medications is not well known. Some of the gastrointestinal medications (e.g., cimetidine) may impact sexual functioning in a quite complex way (i.e., their impact on hormones and hormone receptors may result not only in various types of sexual impairment, such as erectile dysfunction, but also in gynecomastia). Because some of these medications are available over-the-counter (e.g., cimetidine), they may not be mentioned in the list of “prescribed” medications provided by patients. | ||||

| •. | Hormones and other medications used in obstetrics and gynecology (antiandrogens-also used in urology, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, selective estrogen receptor modulators): Sex hormones are usually thought (not always correctly) to be associated with positive changes in sexual functioning. Nevertheless, some of these medications, such as oral contraceptives, may be associated with sexual dysfunction (decreased libido), because exogenous estrogens and progesterones may lead to decreased levels of androgens. | ||||

| •. | Medications used in neurology (antiepileptics, antiparkinsonian medications, migraine medications): As mentioned in the earlier section on mood stabilizers, medications used to treat epilepsy may be associated with sexual dysfunctions (e.g., decreased libido). However, the assessment of sexual dysfunction associated with these medications in patients with epilepsy is difficult due to known hyposexuality in these patients. Also, some of these medications (e.g., carbamazepine) affect the levels of sex hormones and sex hormone-binding globulin. Medications used to treat Parkinson's disease usually do not have a negative impact on sexual functioning and actually may be associated with hypersexuality (Klos et al. 2005). Migraine medications have not been reported to cause sexual dysfunction. | ||||

| •. | Medications used in urology (drugs used for incontinence, drugs used for benign prostatic hypertrophy and/or prostatic cancer): Finasteride, used in benign prostatic hypertrophy, may be associated with erectile dysfunction or delayed ejaculation. The TCA imipramine, used in enuresis and occasionally in incontinence, is associated with erectile dysfunction and other impairment of sexual functioning. | ||||

Other medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or even topical glaucoma medication (timolol, a beta-blocker), may occasionally be associated with various sexual dysfunctions. Some of the medications used for treatment of substance abuse have been reported to be associated with sexual dysfunction (e.g., methadone has been associated with erectile dysfunction; Hallinan et al. 2008), but others have not (e.g., buprenorphine; naltrexone, which has been actually tested for treating erectile dysfunction).

SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND TOXINS

Although the focus of this chapter is on sexual dysfunction associated with medications, sexual dysfunctions also may be associated with recreational drugs (alcohol, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, nicotine), especially when used chronically (Palha and Esteves 2008). Similarly, numerous workplace toxins (e.g., carbon disulfide, chlordecone, manganese, nitrous oxide, stilbene, trinitrotoluene) may be associated with sexual dysfunctions (Segraves and Balon 2003).

MANAGEMENT OF SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION ASSOCIATED WITH MEDICATIONS

The management of sexual dysfunction associated with medications starts with the initial evaluation of the patient. The clinician has to carefully evaluate the patient's sexual functioning at baseline, prior to starting any medication (for discussion of evaluation, see Chapter 2). Nothing can replace a thorough baseline evaluation. The clinician cannot rely on patient memory in making sure that the sexual dysfunction definitely started after the onset of treatment. Also, because the “cause” of sexual dysfunction can be quite complicated, considerations should include the presenting disorder, the possibility of one or more comorbid disorders (mental and/or physical), more than one medication, interpersonal problems, and even primary sexual dysfunction.

An important part of the baseline evaluation is proactive, pointed questioning. The clinician should ask very specific questions, not general, vague ones. Proactive and specific questioning should continue during follow-up visits and should become part of the clinician's routine, not occurring just in response to a patient's spontaneous reporting of sexual dysfunction (as mentioned earlier, spontaneous reporting and active questioning lead to differences in the numbers of reports of sexual dysfunction associated with medication; see Landen et al. 2005). Some clinicians may decide to use questionnaires completed by patients or by clinicians (see Chapter 2). Patients' self-reports should always be followed by a clinical interview, including going over the questions and possibly asking additional ones (for examples of questions about sexual functioning, see Table 2-2 in Chapter 2). Laboratory testing is almost never necessary in evaluating medication-associated sexual dysfunction (an exception may be measuring prolactin levels in antipsychotic-associated sexual dysfunction).

The clinician should also obtain information about the patient's use of over-the-counter medications, herbal preparations, and contraceptives, and about possible substance abuse (including nicotine and alcohol). The effect of a treated illness (e.g., depression, anxiety, cancer, hypertension, coronary artery disease) on sexual functioning should also be considered. Some preventable and/or treatable risks or factors, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, sleep apnea, or smoking, may be contributing to the sexual dysfunction. Addressing these risks or factors may either decrease the need for the medication that is causing sexual dysfunction or improve the patient's general physical well-being and possibly sexual functioning.

The clinician should also actively discuss the possibility of medication-associated sexual dysfunction with the patient. Patients appreciate being informed by the physician and being part of the clinical decision making, and some patients may have heard that sexual dysfunction may be associated with their medication. Inviting the partner to discuss sexual activity may also be helpful.

For patients with certain diseases, the discussion of sexual activity prior to treatment may include some practical tips (Segraves and Balon 2003). For example, for patients with cardiovascular disease, especially during the post-myocardial infarction period, these tips may include suggestions of avoiding sex after meals (wait 3 hours) or after alcohol consumption; avoiding sex in extreme temperatures; avoiding sex when tired or fatigued; avoiding sex during periods of extreme stress; and reporting to the treating physician any unusual symptoms (e.g., chest pain, long palpitations, marked fatigue, sleeplessness) that occur during or after sexual activity.

Several strategies have been used in the management of sexual dysfunction associated with medications, most of which were used originally for the management of antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction. Most of these strategies have not been properly evaluated in a gold-standard, double-blind placebo fashion and probably never will be evaluated in this fashion. As Taylor et al. (2005) pointed out in their analysis of management strategies for antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction, only the addition of sildenafil or tadalafil and possibly bupropion seem to be effective strategies, supported by relatively solid evidence. Thus, the use of management strategies remains a clinical art rather than a science. Again, a complete review of evidence is beyond the scope of this chapter, and the interested reader is referred to the book by Segraves and Balon (2003).

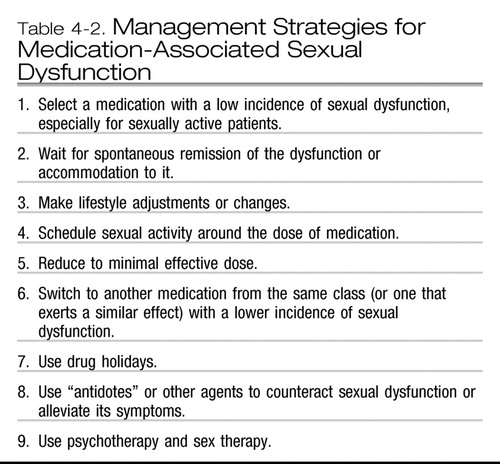

Management strategies for medication-associated sexual dysfunction are discussed below and are summarized in Table 4-2. Importantly, none of the medications mentioned in the management strategies of medication-associated sexual dysfunction has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for these indications.

| 1. | Select a medication with a low incidence of sexual dysfunction, especially for sexually active patients. This proactive strategy may be quite helpful for sexually active patients. In the case of antidepressants, one may choose bupropion, mirtazapine, moclobemide, or nefazodone as the initial treatment of depression or some of the anxiety disorders. Similarly, in the case of antipsychotics, one may choose either any of the atypical antipsychotics, or some of the older antipsychotics, such as loxapine or molindone, that are reportedly associated with a lower incidence of sexual dysfunction. Among antihypertensives, one may choose captopril, which reportedly has been associated with a lower incidence of sexual dysfunction. | ||||

| 2. | Wait for spontaneous remission of the dysfunction or accommodation to it. This strategy is rarely used because “remission” rates are quite low and the time to achieve remission could be quite long (6 months), and even waiting for that long may not work. In addition, this strategy may be acceptable only to patients with a low frequency of sexual activity. | ||||

| 3. | Make lifestyle adjustments or changes. Some lifestyle changes, such as smoking and substance abuse cessation, exercise, and weight loss, may contribute to the improvement of sexual functioning. However, no matter whether intuitively correct and recommended by some clinicians, the efficacy of lifestyle changes has not been demonstrated in the management of medication-associated sexual dysfunction. | ||||

| 4. | Schedule sexual activity around the dose of medication. The patient may be advised to get involved in sexual activity prior to taking the entire daily dose of medication suspected of causing the sexual dysfunction. Although this strategy has been suggested by some clinicians, it has not been properly tested. | ||||

| 5. | Reduce to minimal effective dose. This strategy seems logical, and evidence indicates that sexual dysfunction in some cases may be dose dependent. This strategy has been frequently suggested in the management of erectile dysfunction, and it may be helpful for patients who are bothered also by other side effects. However, this strategy may be clinically problematic, because the likelihood of relapse or medication discontinuation symptoms may increase with a decreased dose. | ||||

| 6. | Switch to another medication from the same class (or one that exerts a similar effect) with a lower incidence of sexual dysfunction. This strategy is basically the same as the first discussed strategy-selection of a medication with a lower incidence of sexual dysfunction-but after the sexual dysfunction has developed. The clinician may decide to switch to a medication within the class (the evidence is weak) or out of the class. Examples in the case of antidepressants may include switching from one MAOI to another, such as from phenelzine to moclobemide (within-class switch), or from an SSRI to either bupropion, nefazodone, or mirtazapine (out-of-class switch). Other examples include switching to antipsychotics mentioned earlier (atypical antipsychotics, loxapine, molindone) or switching from a benzodiazepine to bupropion. | ||||

| 7. | Use drug holidays. This strategy is based on one small study (Rothschild 1995) in which paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine were stopped for a few days in patients with sexual dysfunction associated with these antidepressants, and sexual activity was recommended at the end of this “holiday,” just prior to restarting the antidepressant. The strategy did not work for fluoxetine-associated sexual dysfunction, probably due to this drug's long half-life. This strategy seems to be problematic, because it may reinforce nonadherence and because discontinuation symptoms may occur when taking a break from medications with a short half-life. The strategy has not been tested in any other class of medications. | ||||

| 8. | Use “antidotes” or other agents to counteract sexual dysfunction or alleviate its symptoms. Although numerous “antidotes” or drugs that counteract sexual dysfunction associated with medications have been described in the literature, the evidence from double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, as pointed out by Taylor et al. (2005), is mostly nonexistent or weak. Most of the evidence comes from case reports, case series, or open trials. Some antidotes have been tried based on consideration of their mechanism of action (e.g., dopaminergic drugs for medication-associated low libido), and others have been tried based on an accidental finding (buspirone improving sexual functioning of anxious patients; Othmer and Othmer 1987). The antidotes used in antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction include amantadine, bethanechol, bromocriptine, bupropion, cyproheptadine, dextroamphetamine, ginkgo biloba, granisetron, loratadine, methylphenidate, mirtazapine, nefazodone, neostigmine, sildenafil, tadalafil, trazodone, vardenafil, and yohimbine. Many of these have side effects of their own (e.g., sedation with cyproheptadine, anxiety with yohimbine), and the efficacy of some (e.g., ginkgo biloba) has been questioned. As mentioned before, the best evidence (Taylor et al. 2005) exists for using sildenafil and tadalafil for antidepressant-associated erectile dysfunction and for using bupropion for antidepressant-associated low libido. A recent small study suggested the possible usefulness of sildenafil in female sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressants (Nurnberg et al. 2008). PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil) have been attempted in other medication-associated sexual dysfunctions (e.g., antipsychotic-associated ones). The use of PDE5 inhibitors requires a bit of caution: these drugs are contraindicated in patients taking nitrates, because fatal hypotension may develop, and PDE5 inhibitors should be used carefully in patients with recent (within 6 months) cardiovascular disease (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina), resting hypotension (blood pressure <90/50) or hypertension (blood pressure >170/110), or retinitis pigmentosa. PDE5 inhibitors have usually been used prior to planned sexual activity, although a recent report suggests that a low dose of tadalafil (5 mg/day) may be useful in treating erectile dysfunction (Forst et al. 2008). It may be only a matter of time before this approach will be suggested for medication-associated sexual dysfunction. Various gels and lubricants could possibly be used for impaired female arousal associated with medication, but solid evidence is lacking. | ||||

| 9. | Use psychotherapy and sex therapy. This approach has not been formally tested. The use of cognitive-behavioral therapy and other therapy modalities to decrease anxiety associated with medication use or sexual performance could theoretically be useful. Similarly, sex therapy and sex education may be helpful in general but remains untested in this indication. | ||||

|

Table 4-2. Management Strategies for Medication-Associated Sexual Dysfunction

Final remark regarding the management of medication-associated sexual dysfunction

The management of medication-associated sexual dysfunction should be tailored to the type of dysfunction (e.g., dopaminergic drugs or stimulants for decreased libido, PDE5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction), the type of medication “causing” the sexual dysfunction, the type of underlying illness (e.g., avoiding use of yohimbine in anxious patients), the patient's comfort, and the physician's expertise and skills.

MEDICATIONS USED FOR PRIMARY SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Many medications have been used for the treatment of primary sexual dysfunctions in recent years, as discussed throughout this book. These medications include hormones (e.g., testosterone) and bupropion for low libido (see Chapter 5, “Disorders of Sexual Desire and Subjective Arousal in Women,” and Chapter 6, “Male Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder”); PDE5 inhibitors, apomorphine, phentolamine, yohimbine, intraurethral or intracorporeal alprostadil, and other medications for male erectile disorder (see Chapter 8, “Male Erectile Disorder”); using these agents, arginine, and lubricants for female arousal disorder (see Chapter 7, “Female Sexual Arousal Disorders”); and SSRIs, clomipramine, and anesthetizing creams (used locally) for premature ejaculation (see Chapter 10, “Delayed and Premature Ejaculation”). On the other hand, many pharmacological agents, substances of abuse, and herbal remedies (e.g., ginkgo biloba) touted for these indications do not work or lack solid evidence beyond case reports.

Case example

A 40-year-old divorced female started taking fluoxetine 20 mg/day for depression, low energy, poor sleep, and low appetite. At the time of her initial evaluation, she confided that she was sexually active with her boyfriend and had no problems achieving orgasm. During her follow-up visit a month later, she felt a bit more depressed because “I had some arguments with my boyfriend regarding his and my kids.” When asked about her sexual functioning, she hesitantly responded that her “sex life was OK.” However, when asked specifically about her ability to reach orgasm, she reported that it “takes me much longer to come than before, and it happened that I was not able to come at all. You know, we have had some problems with kids, and I don't feel very excited about sex.” Because the sexual dysfunction 1) might have been causing some problems in her relationship with her boyfriend and 2) might have been related to fluoxetine, she agreed to the clinician's suggestion that she switch to bupropion. She reported improved mood and a return to premorbid (i.e., prefluoxetine) sexual functioning a month later.

This case illustrates several points made in this chapter: 1) the importance of baseline evaluation, 2) the importance of active questioning at baseline and during follow-up visits, and 3) the fact that patients may interpret their sexual dysfunction as a consequence of interpersonal and other problems when it could be associated with medication.

KEY POINTS

| •. | Sexual dysfunction may occur with almost any medication, may be dose dependent, and is fairly frequent with some psychotropic medications, such as antidepressants. | ||||

| •. | Physicians should not rely on a patient's spontaneous reporting of sexual dysfunction associated with medication. They should take a proactive stance and ask specifically about sexual dysfunction, the type and duration, and so forth. They should also monitor for possible sexual dysfunction during the administration of medication. | ||||

| •. | Baseline evaluation of sexual function-that is, evaluation prior to starting a medication—is absolutely necessary for detecting, assessing, and managing sexual dysfunction associated with medications. | ||||

| •. | The contribution of other factors, such as the treated illness, comorbid illness, substance abuse, and interpersonal problems, should not be underestimated in the evaluation and management of medication-associated sexual dysfunction. | ||||

| •. | Management of medication-associated sexual dysfunction should be tailored to the type of sexual dysfunction, medication used, underlying treated illness, patient comfort, and physician skills. | ||||

| •. | Several strategies are useful in managing medication-associated sexual dysfunction, as summarized in Table 4-2. Solid evidence beyond case reports or case series for using these strategies is usually weak or nonexistent. The best existing evidence supports use of PDE5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction and bupropion for low libido. | ||||

Adler L, Dietrich A, Reimherr FW, et al: Safety and tolerability of once versus twice daily atomoxetine in adults with ADHD. Ann Clin Psychiatry 18: 107–113, 2006Crossref, Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

Baldwin DS: Depression and sexual function. J Psychopharmacol 10 ( suppl 1): 30– 34, 1996Google Scholar

Beaumont G: Sexual side effects of clomipramine. J Int Med Res 51: 37–44, 1977Google Scholar

Bolton JM, Sareen J, Reiss JP: Genital anesthesia persisting six years after sertraline discontinuation. J Sex Marital Ther 32: 327–330, 2006Crossref, Google Scholar

Clayton AH, Montejo AL: Major depressive disorder, antidepressants, and sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry 67 ( suppl 6): 33– 37, 2006Google Scholar

Crenshaw TL, Goldberg JP: Sexual Pharmacology: Drugs That Affect Sexual Function. New York, WW Norton, 1996Google Scholar

Csoka AN, Shipko S: Persistent sexual side effects after SSRI discontinuation. Psychother Psychosom 75: 187–188, 2006Crossref, Google Scholar

Forst H, Rajfer J, Casabe A, et al: Long-term safety and efficacy of tadalafil 5 mg dosed once daily in men with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med 5: 2160–2169, 2008Crossref, Google Scholar

Hallinan R, Byrne A, Agho K, et al: Erectile dysfunction in men receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. J Sex Med 5: 684–692, 2008Crossref, Google Scholar

Kelly DL, Conley RR: Sexuality and schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull 30: 767–779, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

Klos KJ, Bower JH, Josephs KA, et al: Pathological hypersexuality predominantly linked to adjuvant dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 11: 381–386, 2005Crossref, Google Scholar

Knegtering H, van den Bosch R, Castelein S, et al: Are sexual side effects of prolactin-raising antipsychotics reducible to serum prolactin? Psychoneuroendocrinology 33: 711–717, 2008Crossref, Google Scholar

Kotin J, Wilbert D: Thioridazine and sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry 133: 82–85, 1976Crossref, Google Scholar

Labbate LA: Psychotropics and sexual dysfunction: the evidence and treatment. Adv Psychosom Med 29: 107–130, 2008Crossref, Google Scholar

Landen M, Hogberg P, Thase ME: Incidence of sexual side effects in refractory depression during treatment with citalopram or paroxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 66: 100–106, 2005Crossref, Google Scholar

Monteiro WO, Noshirvani HF, Marks IM, et al: Anorgasmia from clomipramine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 151: 107–112, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

Montgomery SA, Baldwin DS, Riley A: Antidepressant medications: a review of the evidence for drug-induced sexual dysfunction. J Affect Disord 69: 119–140, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Norden M: Buspirone treatment of sexual dysfunction associated with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Depression 2: 109–112, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al: Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 300: 395–404, 2008Crossref, Google Scholar

Othmer E, Othmer SC: Effect of buspirone on sexual function in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 48: 201–203, 1987Google Scholar

Palha AP, Esteves M: Drugs of abuse and sexual functioning. Adv Psychosom Med 29: 131–149, 2008Crossref, Google Scholar

Rothschild AJ: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction: efficacy of a drug holiday. Am J Psychiatry 152: 1514–1516, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

Safarinejad MR: Evaluation of endocrine profile and hypothalamic-pituitary-testis axis in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced male sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychopharmacol 28: 418–423, 2008Crossref, Google Scholar

Segraves RT: Effects of psychotropic medication on human erection and ejaculation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46: 275–284, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

Segraves RT, Balon R: Sexual Pharmacology: Fast Facts. New York, WW Norton, 2003Google Scholar

Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Hawton K: Strategies for managing antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord 88: 241–254, 2005Crossref, Google Scholar

Zemishlany Z, Weizman A: The impact of mental illness on sexual dysfunction. Adv Psychosom Med 29: 89–106, 2008Google Scholar