Psychiatric Involvement in Obesity Treatment

Abstract

Obesity is a growing concern among all areas of medicine. Psychiatric patients in particular are more likely than the general population to be overweight and suffer from obesity-related comorbidities. Psychiatrists need to be aware of the risks inherent to psychiatric patients, as well as the weight-related side effects associated with many psychiatric medications. However, awareness alone is not sufficient. Psychiatrists are being asked to take on a greater role in weight management because psychiatric patents frequently do not receive such assistance from other physicians. Another role that psychiatrists may become involved in is the evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates. There are several key areas that must be reviewed to identify patients at risk of poor surgical outcomes and sufficiently address those risk factors.

According to the World Health Organization, more than 1 billion adults are overweight and 300 million of these are obese. Results from the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate that an estimated 66% of U.S. adults are either overweight or obese. Overweight is defined using the body mass index (BMI), according to the formula BMI = (weight in kilograms) divided by (the square of height in meters). According to this calculation, those with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater are overweight, and those with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater are obese. Individuals with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater or 35 kg/m2 or greater with medical comorbidities are considered morbidly obese.

Why is obesity of concern to psychiatrists? In addition to the well-known health risks to our patients, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke, and certain forms of cancer, obesity is associated with psychiatric illness (1). Studies of obese individuals reveal high rates of psychiatric comorbidities, including eating disorders (especially binge eating disorder), depression, anxiety, and personality disorders (2). According to one study, men with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater were significantly more likely than normal-weight males to have current depression or a lifetime diagnosis of depression and anxiety. For women, being overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) or obese was associated with a higher prevalence of depression or lifetime diagnosed depression and anxiety (3). A study of personality disorders showed that extreme obesity was associated with antisocial or avoidant personality disorders (4).

Along with the association of psychiatric disorders with obesity, there is also an association of obesity with psychiatric disorders. Obesity is more prevalent in persons with severe mental illness than in the general population (5). In fact, schizophrenia is associated with a threefold increase in diabetes and twofold increase in cardiovascular disease. This association is postulated to be due to the high prevalence of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic individuals (6, 7). The metabolic syndrome is seen in patients with many different psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, and schizophrenia. This relationship between increased weight and schizophrenia is seen even in drug-naive individuals. Drug-naive schizophrenic patients have a threefold increase in central obesity, the type of obesity most strongly correlated with health risks (8). Another aspect to consider is the high rate of smoking among schizophrenic individuals. Smoking may help to manage their propensity for higher weight through an increase in metabolism and decreasing caloric intake. Weight gain is likely to occur upon smoking cessation (9).

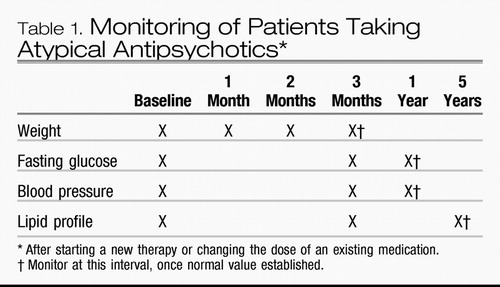

The treatment of psychiatric disorders can exacerbate this risk of obesity. Several psychotropic drugs have been associated with weight gain, including tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, lithium, antiepileptic medications, some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, phenothiazine antipsychotic medications (including thioridazine), and atypical antipsychotic medications (10–17). The atypical antipsychotic medications, in particular, are associated not only with weight gain but also with diabetes and an atherogenic lipid profile (18). The American Diabetes Association, APA, and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists consensus development statement recommend baseline screening and monitoring for patients treated with psychiatric medications, particularly atypical antipsychotic medications (19) (Table 1). If the psychiatrist will not be the one responsible for obtaining these tests, he or she should coordinate with the primary care physician and record the results in the psychiatric record. Of the antidepressants, amitriptyline, mirtazapine, and imipramine have been found to be the most likely to produce weight gain, whereas bupropion and nefazodone are considered least likely (20).

|

Table 1. Monitoring of Patients Taking Atypical Antipsychotics*

Although weight management is not generally considered within the domain of psychiatric care, it may need to be, as it might not be treated by others. In the primary care clinic, patients may not ask for help with weight management, either because they do not realize their weight is a problem or because they doubt their provider's ability to help (21). Studies have found that only 10% to 20% of patients are being counseled to lose weight or are receiving weight management services from their physicians (22, 23). For psychiatric patients, the numbers may be even lower because psychiatric patients tend to avoid medical clinics, are poorly received by medical personnel when they do seek help, and may not have the cognitive ability to navigate complicated health care systems or advocate the care they need (24).

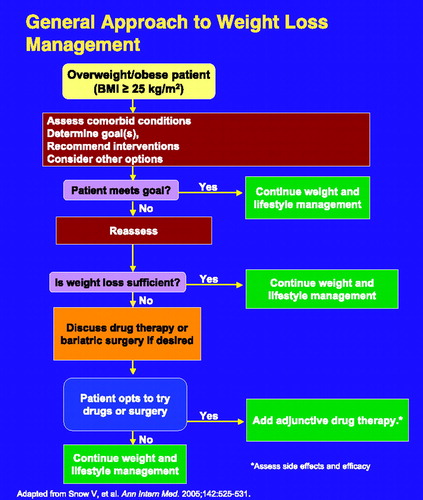

Weight management can seem like a daunting task for both the patient and provider. According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, effective weight management consists of several components including dietary therapy, physical activity, behavior therapy, pharmacotherapy, bariatric surgery, or any combination of these (25). Regardless of the specifics of the management strategy chosen, it is important to elicit the patient's goals and beliefs about weight loss and body image (26). Some patients may have unrealistic expectations about weight loss. They may fantasize about reaching an unrealistic clothing size or want to look like a particular person. Losing the amount of weight they desire thus may become overwhelming and lead them to give up too quickly. It is important for the provider to know the benefits that can be realized with a small amount of weight loss and convey these to the patient. For example, a loss of only 4%–5% can lower or eliminate the need for antihypertensive medication, 5%–7% loss is associated with a 58% reduced risk for type 2 diabetes, and 6%–7% loss can improve metabolic syndrome (27). By focusing on the health benefits associated with a small amount of weight loss, patients can set realistic goals that can be reached sooner, encouraging them to continue. In addition, patients should be encouraged to look at weight loss as a long-term process. Slower weight loss has been found to last longer than the rapid loss patients may desire (28).

TREATMENT STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

To manage the patient's diet, one might provide resources such as a diabetes educator or nutritionist. There are also several commercially available diets that have been found to yield similar results (29). Physical activity can be monitored at each visit. Patients may be more likely to engage in physical activity if they know their provider will be asking about it. Keeping track of diet and exercise patterns is the first step in behavioral treatment of overweight individuals. Keeping a food journal greatly increases one's ability to lose weight because people underestimate the actual amount they eat each day (30). By recognizing what they are eating, they are immediately able to see where changes can be made. If patients add to their food logs the situational context in which they are eating, they can identify the situations that are high risk for overeating and develop ways to avoid them. Some patients may benefit from participating in a social support network that can encourage them and help motivate them to continue their weight loss efforts.

How effective are these techniques in the severely mentally ill? Several studies have shown significant weight loss in schizophrenic patients using behavioral techniques (31–35). One study of a weight loss program in schizophrenic patients showed that even cognitive impairment did not reduce the benefit to an individual in the program (3). However, if the behavioral interventions are not producing the necessary weight loss, consideration of pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery is indicated (37).

Pharmacotherapy

Psychiatrists are in a unique position to manage pharmacotherapeutic options for weight loss, given that many of these agents act through neurochemistry. Obviously, careful attention to other psychiatric medications is important when these drugs are used. One type of medication for weight loss is an appetite suppressant. Sibutramine is a norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitor; phentermine, phendimetrazine, diethylpropion, and benzphetamine act by stimulating sympathomimetic amines. Care should always be taken when giving stimulants to patients with psychoses, anxiety, or panic disorders. In addition to the psychiatric interactions, these medications can also cause insomnia and cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects. It is important to convey to patients that these medications are not magic. Sibutramine, for example, is designed to give a 5%–10% weight loss in an obese individual, if taken in conjunction with diet and exercise. This weight loss can bring significant changes in comorbid conditions; however, it is important for patients to recognize that overall they will most likely still be overweight.

Orlistat works by a different mechanism: as a lipase inhibitor taken with meals, it decreases the body's ability to absorb the fat eaten. Deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins occur as well as gastrointestinal side effects. Orlistat is now approved for over-the-counter use, so it is important to ask whether your patient is taking it.

Despite the precautions that must be observed in using these medications in psychiatric patients, some success has been reported. Schizophrenic patients taking olanzapine and sibutramine lost weight, although those taking clozapine and sibutramine did not (38, 39). Amantadine may lead to weight loss when used with olanzapine, and topiramate (Topamax) has been reported to counter weight gain caused by psychotropic effects (40, 41). However, these medications require further study.

Bariatric surgery

For obese psychiatric patients unable to lose weight with diet, exercise, and medications, bariatric surgery may be an option. This option is reserved for the patients who are most obese and it can be highly effective. On average, patients lose between 40% and 60% of their excess body weight, depending on the type of procedure performed (42). To qualify for bariatric surgery, the patient must have a BMI of at least 40 kg/m2 or 35 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities. There are several different methods of bariatric surgery; some are designed to decrease gastric capacity and cause malabsorption (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and biliopancreatic bypass), whereas others only decrease gastric capacity (laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and vertical banded gastroplasty). Psychiatric patients must be stable and carefully monitored throughout the process, but a diagnosis of a psychiatric condition does not necessarily preclude them from having the surgery. In one study, patients with schizophrenia and morbid obesity underwent bariatric surgery and had weight loss comparable to that of nonpsychotic patients undergoing bariatric surgery (43).

THE PSYCHIATRIC CONSULTANT: BARIATRIC SURGERY

Psychiatrists, particularly those with a specialty in consultation-liaison, may be asked to evaluate a candidate for bariatric surgery. According to a survey of bariatric programs, 88% require candidates to undergo a psychological evaluation (44). These evaluations are advised because of the high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity among bariatric surgery candidates (45). Approximately two-thirds of patients presenting for surgery have a lifetime history of at least one axis I disorder, with 38% meeting the diagnostic criteria at the time of the preoperative evaluation. In addition, almost one-third will meet the criteria for one or more axis II disorders (46).

As with many activities of the consultation-liaison psychiatrist, providing effective care is best accomplished as part of a multidisciplinary team. For a program to be considered a Center of Excellence, the involvement of a mental health professional during the patient selection process is required (47). Despite the recognition of the importance of mental health evaluations, there is little consensus in the way these evaluations are performed. Depending on the center, these may be under the purview of a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or other staff member. Only about half of all programs use standardized testing, and there is no consensus about the types of tests to perform (40). An advantage to using standardized psychometric tests is the numerical value that can be obtained and then followed for changes during future visits.

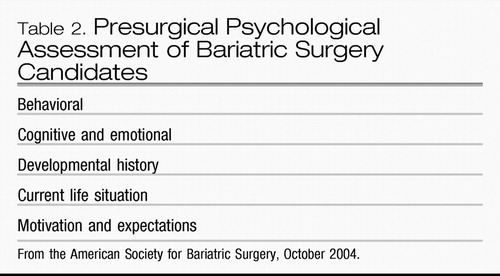

So, how should a psychiatrist approach these evaluations? These evaluations are not merely to decide “yes” or “no” to a patient receiving the surgery, but rather they are an opportunity to explore potential areas of concern and develop a treatment plan to address these. According to the American Society for Bariatric Surgery, several key areas should be addressed. These areas include behavioral, cognitive, emotional, developmental, current life situation, motivation, and expectation (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Presurgical Psychological Assessment of Bariatric Surgery Candidates

The behavioral evaluation assesses the patient's eating habits and dietary style. The patient should be asked about his or her current food intake, including screening for any maladaptive patterns such as binge eating, night eating syndrome, and purging. Binge eating, in particular, is highly associated with overweight (48). The patient's level of physical activity should be assessed, as well as reasons behind a lack of physical activity. The patient should be asked about previous attempts to manage weight, including which aspects were problematic. Did he or she lose weight on a diet but experienced relapse in the face of stressors? Or was he or she unable to follow the diet because of other factors? Other behaviors to be explored include substance abuse, legal history, and health-related risk-taking behavior.

Cognitive function screening can be cursory for most patients but may require more in-depth testing if problems are suspected. Patients need to have knowledge of obesity in general and the proposed surgical intervention. In addition, a patient needs to be able to understand the requirements of postoperative care, including being able to read nutrition labels and do mathematic calculations of the various nutrients needed.

Emotional functioning is vital. Many people use food as a coping mechanism and will need to develop other coping skills to lose weight successfully. An evaluation of psychopathology is also included in the emotional evaluation. Patients should be screened for current symptoms or a past history of psychiatric disorders. If the patient has been hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder, he or she may require 1 year or more of outpatient stability before being considered for surgery. If the patient is currently receiving psychiatric medication, this would need to be evaluated. Are the medications crushable? If not, the medication regimen may need to be changed with patient restabilization before surgery is performed.

The patient's developmental history can elicit educational issues that may cause difficulty with following postoperative requirements. It may also reveal an unstable family background or a history of abuse. Although these would not preclude a patient from receiving surgery, he or she may experience additional stress with a change in body habitus. By initiating psychotherapy before the surgery, these issues could be addressed as the changes are occurring.

Questions about the current life situation would include the patient's financial situation, social supports, living situation, and others. Patients may have significant problems if they are unable to afford the required vitamins and nutrition after surgery. If they have no social support or the people around them are not supportive, their weight loss efforts may be sabotaged.

Finally, the patient's motivations and expectations surrounding the surgery must be examined. Is the patient looking for a quick fix, or does he or she realize that surgery is a tool to assist in their dietary efforts? Patients have expressed the desire for bariatric surgery so they can lose weight without dieting, or they think it will lead to them finding a spouse. Expectations such as these need to be elicited and managed appropriately.

In a survey of bariatric surgery programs of those candidates not accepted for surgery, the most common reasons included substance abuse, active symptoms of schizophrenia, and lack of knowledge about the surgery (40). By revealing such issues in a psychosocial evaluation, appropriate action can be taken to correct them. In this way, the patient can participate in this highly effective treatment and be empowered to have the best outcome possible.

QUESTIONS AND CONTROVERSY

There are questions and controversies that arise when looking at psychiatry and obesity. Although several psychiatric medications are associated with weight gain, the exact mechanism responsible for weight gain is not known. In addition, it is known that psychiatric illness itself may predispose someone to being overweight.

Is weight management by a psychiatrist effective? This remains to be determined. The studies cited in this article are from patients enrolled in weight loss programs.

How predictive are bariatric surgery assessments? As long as patients are psychiatrically stable, there are few indications that psychosocial evaluations predict postoperative outcome. This is an area in need of further standardization and study to determine the effectiveness of these evaluations.

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE AUTHOR

It is important that psychiatrists recognize the interplay of mental health and weight. Because of the association of psychiatric illness and overweight, psychiatrists must consider the unique risks of weight gain and difficulty with weight management in patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatrists must also inform themselves of the metabolic risks associated with various psychotropic medications and reflect this knowledge when choosing to initiate treatment. When these medications are used, psychiatrists need to perform baseline screening and monitor regularly for metabolic complications. For those psychiatrists performing evaluations of bariatric surgery candidates, a thorough assessment can uncover areas to be addressed to have a successful outcome. This role can be an indispensable part of a multidisciplinary bariatric surgery team.

1 World Health Organization: Obesity and overweight. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/facts/obesity/enGoogle Scholar

2 Greenberg I, Perna F, Kaplan M, Sullivan MA: Behavioral and psychological factors in the assessment and treatment of obesity surgery patients. Obes Res 2005; 13: 244– 249Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Zhao G, Ford ES, Dhingra S, Li C, Strine TW, Mokdad AH: Depression and anxiety among US adults: associations with body mass index. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 257– 266Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Mather AA, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Sareen J: Associations between body weight and personality disorders in a nationally representative sample. Psychosom Med 2008; 70: 1012– 1019Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Hoffman V, Ahl J, Meyers A, Schuh L, Shults K, Collins DM, Jensen L: Wellness intervention for patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 1576– 1579Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Casey DE: Metabolic issues and cardiovascular disease in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Med 2005; 118( suppl 2): 15s– 22sGoogle Scholar

7 Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA 1999; 282: 1523– 1529Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Thakore JH, Mann JN, Vlahos I, Martin A, Reznek R: Increased visceral fat distribution in drug-naive and drug-free patients with schizophrenia. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002; 26: 137– 141Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Devlin MJ, Yanovski SZ, Wilson GT: Obesity: what mental health professionals need to know. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 854– 866Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Harvey BH, Bouwer CD: Neuropharmacology of paradoxic weight gain with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin Neuropharmacol 2000; 23: 90– 97Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Fava M: Weight gain and antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61( suppl 11): 37– 41Google Scholar

12 Vendsborg PB, Bech P, Rafaelsen OJ: Lithium treatment and weight gain. Acta Psychiatry Scand 1976; 53: 139– 147Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Biton V: Effect of antiepileptic drugs on bodyweight: overview and clinical implications for the treatment of epilepsy. CNS Drugs 2003; 17: 781– 791Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Charatan FB, Bartlett NG: The effect of chlorpromazine (Largactil) on glucose tolerance. J Ment Sci 1955; 101: 351– 353Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Allison DB, Casey DE: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62( suppl 7): 22– 31Google Scholar

16 Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, Weiden PJ: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156: 1686– 1696Google Scholar

17 Baptista T: Body weight gain induced by antipsychotic drugs: mechanisms and management. Acta Psychiatry Scand 1999; 100: 3– 16Crossref, Google Scholar

18 American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 596– 601Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001; 285: 2486– 2497Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Collazo-Clavell ML, Clark MM, McAlpine DE, Jensen MD: Assessment and preparation of patients for bariatric surgery. Mayo Clin Proc 2006; 81( 10 suppl): S11– S17Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Ruelaz A, Diefenbach P, Simon B, Lanto A, Arterburn D, Shekelle PG: Perceived barriers to weight management in primary care—perspectives of patients and providers. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22: 518– 522Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Sciamanna CN, Tate DF, Lang W, Wing RR: Who reports receiving advice to lose weight? Results from a multistate survey. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 2334– 2339Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Ruser CB, Sanders L, Brescia GR, Talbot M, Hartman K, Vivieros K, Bravata DM: Identification and management of overweight and obesity by internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20: 1139– 1141Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Wirshing DA: Schizophrenia and obesity: impact of antipsychotic medications. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65( suppl 18): 13– 26Google Scholar

25 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 1998Google Scholar

26 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Guide to Behavior Change. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/obesity/lose_wt/behavior.htmGoogle Scholar

27 Parks J, Radke A: Obesity Reduction & Prevention Strategies for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. http://www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/Obesity%2010-8-08.pdfGoogle Scholar

28 Paisey RB, Frost J, Harvey P, Paisey A, Bower L, Paisey RM, Taylor P, Belka I: Five year results of a prospective very low calorie diet or conventional weight loss programme in type 2 diabetes. J Hum Nutr Diet 2002; 15: 121– 127Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Bray GA: Lifestyle and pharmacological approaches to weight loss: efficacy and safety. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93( 11 suppl 1): S81– S88Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Hollis JF, Gullion CM, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Ard JD, Champagne CM, Dalcin A, Erlinger TP, Funk K, Laferriere D, Lin PH, Loria CM, Samuel-Hodge C, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP; Weight Loss Maintenance Trial Research Group: Weight loss during the intensive intervention phase of the weight-loss maintenance trial. Am J Prev Med 2008; 35: 118– 126Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Ball MP, Coons VB, Buchanan RW: A program for treating olanzapine-related weight gain. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52: 967– 969Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Littrell KH, Hilligoss NM, Kirshner CD, Petty RG, Johnson CG: The effects of an educational intervention on antipsychotic-induced weight gain. J Nurs Scholarsh 2003; 35: 237– 241Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Vreeland B, Minsky S, Menza M, Rigassio Radler D, Roemheld-Hamm B, Stern R: A program for managing weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54: 1155– 1157Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Menza M, Vreeland B, Minsky S, Gara M, Radler DR, Sakowitz M: Managing atypical antipsychotic-associated weight gain: 12-month data on a multimodal weight control program. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65: 471– 477Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Brar JS, Ganguli R, Pandina G, Turkoz I, Berry S, Mahmoud R: Effects of behavioral therapy on weight loss in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 205– 212Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Jean-Baptiste M, Tek C, Liskov E, Chakunta UR, Nicholls S, Hassan AQ, Brownell KD, Wexler BE: A pilot study of a weight management program with food provision in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2007; 96: 198– 205Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Snow V, Barry P, Fitterman N, Qaseem A, Weiss K, Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians: Pharmacologic and surgical management of obesity in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 525– 531Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Henderson DC, Copeland PM, Daley TB, Borba CP, Cather C, Nguyen DD, Louie PM, Evins AE, Freudenreich O, Hayden D, Goff DC. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sibutramine for olanzapine-associated weight gain. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 954– 962Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Henderson DC, Fan X, Copeland PM, Borba CP, Daley TB, Nguyen DD, Zhang H, Hayden D, Freudenreich O, Cather C, Evins AE, Goff DC. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sibutramine for clozapine-associated weight gain. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007; 115: 101– 105Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Graham KA, Gu H, Lieberman JA, Harp JB, Perkins DO: Double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of amantadine for weight loss in subjects who gained weight with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1744– 1746Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Lévy E, Agbokou C, Ferreri F, Chouinard G, Margolese HC: Topiramate-induced weight loss in schizophrenia: a retrospective case series study. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 14: e234– e239Google Scholar

42 Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Fabricatore AN: Psychosocial and behavioral aspects of bariatric surgery. Obes Res 2005; 13: 639– 648Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Hamoui N, Kingsbury S, Anthone GJ, Crookes PF: Surgical treatment of morbid obesity in schizophrenic patients. Obes Surg 2004; 14: 349– 352Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Bauchowitz AU, Gonder-Frederick LA, Olbrisch ME, Azarbad L, Ryee MY, Woodson M, Miller A, Schirmer B: Psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates: a survey of present practices. Psychosom Med 2005; 67: 825– 832Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA, Courcoulas AP: Psychiatric evaluation and follow-up of bariatric surgery patients. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166: 285– 291Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, Courcoulas AP, Pilkonis PA, Ringham RM, Soulakova JN, Weissfeld LA, Rofey DL: Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 328– 334Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Bradley DW, Sharma BK: Centers of Excellence in Bariatric Surgery: design, implementation, and one-year outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006; 2: 513– 517Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Devlin MJ: Is there a place for obesity in DSM-V? Int J Eat Disord 2007; 40: S83– S88Crossref, Google Scholar