Optimizing Outcomes in Psychopharmacology Continuing Medical Education (CME): Measuring Learning and Attitudes That May Predict Knowledge Translation into Clinical Practice

Abstract

Because continuing medical education (CME) activities in psychopharmacology have traditionally documented only that participants have been exposed to a great deal of new information, it has been difficult to gauge to what extent CME leads to the acquisition of new knowledge or to the translation of this knowledge into clinical practice. The goal of modern CME is not only to facilitate learning and knowledge translation, but to evaluate whether these outcomes have occurred. Although further research will be required to develop practical, affordable, and proven methods that are capable of measuring the extent to which a CME activity facilitates sustained knowledge translation into clinical practice, it is already possible to incorporate participant-focused educational designs, measurements of learning with pre-and posttesting, and case-based exercises to assess whether the translation of knowledge into proxies of clinical practice is now beginning to occur.

Clinical context: How well does continuing medical education “work”?

An ongoing debate in psychopharmacology as well as in many fields of medicine is whether continuing medical education (CME) “works” and if so, what that means and whether that is a good thing. On the one hand, numerous academic studies suggest that it does not work. That is, live meetings, written materials, and other ways of presenting new information to practitioners may not make any notable or sustained difference in how medical or psychiatric conditions are diagnosed or monitored or whether evidence-based treatments or consensus treatment guidelines are applied in actual clinical practice (1–8). On the other hand, many critics simultaneously suggest that CME works all too well. Namely, there is a hue and cry that CME is too heavily influenced by the pharmaceutical industry and you get all the CME that they pay for. Thus, CME may lead participants to increase their use of sponsors’ drugs but not necessarily to improve their best practice standards (9–13).

How can these apparently conflicting points of view about whether CME can change participants’ behavior be reconciled? Perhaps the real question is not whether CME works, but rather, how can CME be designed, implemented, and evaluated to best facilitate learning, lead to transfer of knowledge into clinical practice, improve the skills of practitioners, and enhance the mental health outcomes of their patients?

Outcomes: If you do not know where you are going, any road will take you there

Documenting whether or not CME changes practitioner behavior in psychopharmacology or in other areas of medicine may be difficult because CME activities are usually designed to deliver a different outcome: namely to expose a large number of practitioners to a flood of new information that is constantly entering clinical medicine and to do this by having practitioners log in a certain number of hours of exposure every year. This outcome has been achieved.

However, only recently has a consensus emerged that modern CME should be going somewhere else and achieving something more ambitious. That is, where CME is now going is toward a much more ambitious outcome than just having participants log in their exposure to content. CME is now being asked to make better practitioners by providing activities that change their behaviors and improve their skills in clinical practice (14, 15, 16). Furthermore, modern CME is also being asked to document that this outcome has been achieved after the completion of specific educational activities (14, 15).

It should be no surprise that educational activities designed only to expose practitioners to massive amounts of information may fail to change behavior. Furthermore, outcome methods designed only to document attendance and whether participants agree that educational objectives are met do not measure whether clinical practice behaviors have changed or whether skills have improved in a clinical practice setting.

The truth of the matter is that there are no currently available methods that are practical, affordable, and capable of measuring with a high degree of confidence whether clinical practice and patient outcomes have improved as a consequence of participation in specific CME activities. Thus, new outcome measures must be developed to document whether or not that outcome has resulted. In the meantime, however, it is certainly possible to evaluate outcomes at higher levels than are currently being done by most ongoing CME activities.

Educational strategies and evidence for how to measure psychopharmacology CME outcomes: Be careful what you ask for (you might get it)

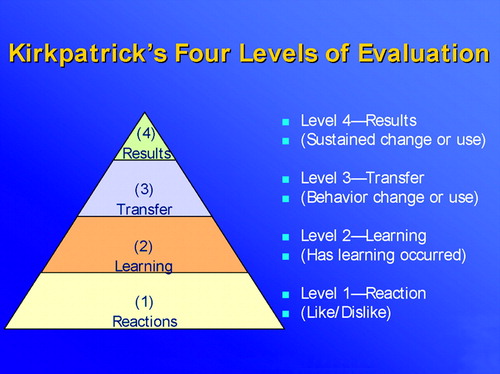

Kirkpatrick (17) has defined four levels of evaluation for educational activities (Figure 1). Although these can be applied to measurement of outcomes of CME activities, this is rarely done beyond the lowest level (i.e., logging attendance and asking whether participants liked the activity). The ultimate goal of modern CME is sustained changes in clinical practice that improve patient outcomes, but it does not yet seem to be possible to attain these high-level evaluations of outcome from CME activities because of the lack of practical, affordable, and validated measures for this outcome.

If evaluations at the highest level are currently out of reach, is it possible to do better than just the lowest level of evaluation that is typical of CME activities? Affordable and reliable methods to attain level 2 evaluations (whether learning occurs) and possibly level 3 evaluations (whether knowledge is beginning to be transferred into use) of outcome are available (Figure 1) (17) but are rarely implemented in CME activities. Is it time to upgrade the evaluations of CME activities to include level 2 and level 3 outcomes (Figure 1) (17)? Here we will discuss not only methods that can document whether learning has occurred but also several new ideas about how to measure the possibility that this learning might transfer into behavioral changes that will be implemented in clinical practice.

Level 1: Psychopharmacology CME evaluations merely measure reactions: A “smile sheet” is no longer an adequate measure of outcome in psychopharmacology CME

For many years, the principal outcome measure of CME has been the level 1 evaluation: who attended?; for how long did they attend?; did they like the speakers?; did they like the handout?; did they like the facility?; did they like the topic?; did they think that the program met the objectives?, and so on. Such evaluations or “smile sheets” have many problems, including the facts that many participants do not complete them or turn them in and that those who do may represent a skewed populations of participants who had the strongest reactions—not necessarily the typical reactions—to the activity. Level 1 evaluations (Figure 1) (17) are often conducted by anecdotal methods that are hard to quantify, such as “positive buzz,” verbal comments, follow-up voicemail messages, and the number of “butts in seats,” with the assumption that events with high degrees of attendance are necessarily successful.

Level 2: Measures learning: Easy to do but rarely done

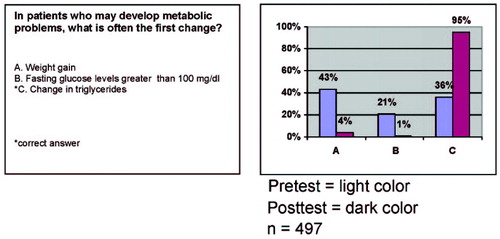

Kirkpatrick’s (17) level 2 evaluation is to assess acquisition of new knowledge (Figure 1). Because planning for a CME activity begins with a needs analysis that identifies gaps in knowledge of the targeted participants, questions for the participant to answer that will document the lack of knowledge found in the needs analysis before beginning the CME activity can be readily developed. For example, Figure 2 shows a question written for a psychopharmacology CME activity designed to address the unmet need of psychiatrists to better understand metabolic issues affecting their patients who receive treatment with atypical antipsychotics. This question was asked of 497 psychiatrists and other mental health participants attending a recent Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharmacology Academy, a live CME activity in New York City in 2006, utilizing audience response keypads (e.g., 17) both to document the number of participants who answered the question and to tally the specific numbers of correct and incorrect responses to this question. The question was first posed as a pretest, and the responses before the lecture document that only about one-third of participants answered this question correctly. However, immediately following the lecture, the posttest showed that 95% of participants answered this question correctly. The audience received this feedback immediately as a pretest-to-posttest comparison. Thus, learning on this key point was documented to the audience, to the speaker, and to the CME program organizers for evaluation of Kirkpatrick (17) level 2 outcomes (Figure 1), namely that learning had occurred.

Documenting learning has many important applications that can be used to modify and evaluate the CME activity. According to Kirkpatrick (17) and others (18–21), learning, mastery, and confidence in new information (level 2) is a precursor to transferring this information into new skills or behavioral change (level 3). Thus, at a minimum, learning should be documented in CME activities as a necessary but not sufficient outcome for improving clinical practice. Although not everyone who learns will change their behavior or improve their practice, it is difficult to conceive how anyone would make changes in their clinical practice if they have not learned anything.

Making use of documentation of what is learned

Measuring learning by evaluating correct responses to factual questions has many uses in the evaluation, design, and revision of psychopharmacology CME activities (18–21). For example, if participants do not answer correctly after a lecture, the speaker can immediately go over this point and reinforce the correct answer. Sometimes, a speaker is not aware of having confused the audience, and the number of correct responses can even go down after the lecture. Seeing this result in the posttest allows the speaker to immediately adjust the presentation to quickly correct the audience misperception or his or her inadvertent misstatement, before going on to other matters and leaving the audience confused or misinformed. Later, the content can be reevaluated to determine whether the answer was clear from the presentation. This is a type of formative test strategy that can be used not only to query the audience but also to revise the content over time.

Second, it is possible that most of the participants already know the answer to the pretest question (a not infrequent finding from pretest questioning). When this occurs, the speaker can go through the material rapidly during the lecture, and, subsequently, the needs analysis can be updated if the answers demonstrate that there is no longer an un-met need on this topic. Because writing questions is a definite art, if participants already know the answer before the lecture or if the number of correct responses does not improve after the lecture, the problem could be that the question needs to be rephrased.

Third, results from pre- and posttesting of learning can be used to evaluate speakers. This is especially true for courses in which the same materials are presented by different speakers to similar audiences. At the beginning of a lecture, the speaker is aware from the pretest how much potential learning there is for a given audience. In the example of Figure 2, only 36% indicated the correct answer. Thus, there was a potential learning on this point of at least 64%. After the lecture, 95% answered the question correctly, so most of the potential learning was fulfilled. This should be the goal of each CME activity. If some speakers are able to get better fulfillment of the potential learning than others, this is one way to evaluate and provide feedback on effectiveness to a faculty of presenters. The goal is to write questions that document the expected knowledge gap before the lecture, then to present materials that effectively teach the information to fill this gap, and finally to document that this potential learning has been largely fulfilled by each presenter.

Much can be done with skilled question writing, integrated with targeted content development and speaker preparation and combined with automated audience response keypad systems to document learning in CME activities. The standard for CME outcomes at this point should be at a minimum to move from level 1 to level 2 outcomes (Figure 1) (17), namely, to document that learning has occurred.

Questions and controversies

Level 3: Transfer from knowledge to practice: The current frontier

Kirkpatrick’s (17) level 3 (Figure 1) is to assess whether knowledge is passing into action or being applied in clinical practice, and this is a very hot topic in CME today (15). Psychopharmacology CME is not about knowledge for knowledge’s sake but about learning that leads to improvement in clinical practice. It is quite difficult to show when or whether learning something about treatment, diagnosis, and laboratory testing leads to transfer of this information into use in clinical practice (1–8). Methods for measuring whether such transfer has occurred have many problems and limitations. Thus, surveys (small number returned), focus groups (nonrandom and probably not representative samples), prescription audits (extremely expensive and structured for commercial applications, not best practices analyses), and chart audits (expensive and confidentiality issues) are all examples of flawed methods in the attempt to show that learning in CME can transfer into behavioral changes in practice (1–8, 22, 23). It is not surprising that there is currently significant questioning as to whether transfer can be measured. This leads in turn to the controversy over whether CME activities are even capable of facilitating such a transfer because it has arguably never been adequately demonstrated.

A more realistic goal than to attempt to measure actual transfer of knowledge into clinical practice may be to show that the information presented and learned in a CME activity is actually applied later in that same CME activity through an exercise emulating clinical practice or as reflected in answers to questions about attitudes, levels of confidence, or intention to change clinical practice (23, 24). At best, such outcomes are merely proxies for what really happens in a clinical practice setting, yet these proxies can be measured as part of any CME activity, and, thus, a determination can be made as to whether the knowledge is being transferred at least to model cases by using exercises in which participants “practice by doing” (21, 25) Rarely, however, are such proxies developed, measured, or evaluated. More research is clearly needed to determine whether clinical case exercises and monitoring of attitudes and intentions are genuinely predictive of changes in clinical practice, but, for now, transfer of knowledge to case exercises and documentation of attitude changes are measurable, attainable, and intuitively attractive outcomes that can begin to address Kirkpatrick’s (17) level 3 evaluations of transfer of knowledge to use in clinical practice.

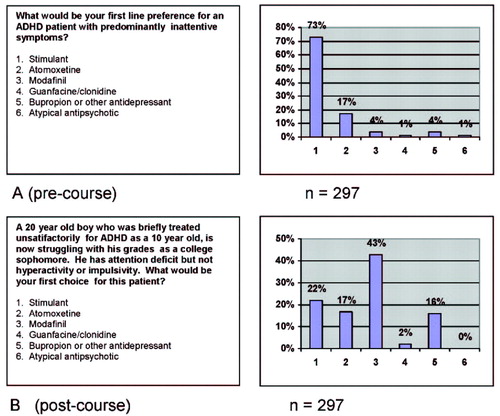

For example, an audience of 297 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals attending the Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharmacology Academy in San Francisco in 2006 was asked before the course about their preferred treatment for patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) who have predominantly inattentive symptoms. Their responses are shown in Figure 3A. Although there is no completely correct or incorrect answer here, the results agree with previous needs analyses (Neuroscience Education Institute, unpublished data) showing that most practitioners feel that stimulants are greatly preferred for such patients. However, many psychiatrists treating adults are not willing to treat anyone with stimulants and thus decline to treat ADHD in adults at all. To encourage more treatment of ADHD in adults, a CME activity was developed to outline alternatives to treating inattentive symptoms with stimulants only, and participants were asked after this activity to again indicate what their preference was for a patient with ADHD with predominantly inattentive symptoms (Figure 3B). The posttest in Figure 3B utilizes a very short and simple case vignette (24, 26) to capture treatment preferences for this patient type and documents a shift away from stimulants to other alternatives.

Another technique to begin the process of measuring Kirkpatrick (17) level 3 transfer of knowledge into action (Figure 1) is to ask about intent to change. Such shifts in attitudes may precede actual behavioral changes (27, 28), and questioning participants about their attitudes could potentially show whether there is at least an intent to transfer knowledge into practice. Although research is still clarifying to what extent intent to change actually presages actual behavior changes (27, 28), it seems highly unlikely that any behavior changes will occur if a CME participant does not even intend to change behavior.

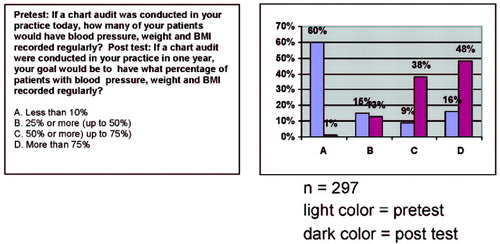

An example of documentation of intent to change is shown in Figure 4. Before hearing lectures on monitoring metabolic changes in psychiatry, the 297 participants at the Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharmacology Academy in San Francisco in 2006 were asked how many of their patients currently have their blood pressures, weights, and body mass indices measured and recorded regularly. A very low number was indicated. After the lectures on monitoring metabolic status in psychiatry, the audience was asked how many patients they think should have these items measured and recorded regularly, and the results showed a huge shift upward. Whether these participants will actually attain these goals is unknown, but this attitude shift would seem to be a necessary precursor to any actual behavior change.

Level 4: sustained transfer of new knowledge to clinical practice leading to positive results in patients: the hope for the future

The highest level of assessment of Kirkpatrick (17) is level 4, namely, to determine whether any knowledge translation has been sustained, and if so, whether it has been effective in improving clinical practice and ultimately in enhancing patient outcomes (Figure 1). It is one thing to learn something (level 2) and another thing to transfer learning into use (level 3), but it is quite an ambitious undertaking to consider transferring the type of knowledge that really changes clinical outcomes in patients into practice and to sustain that transfer rather than reverting to prior practices or to bad habits. The goal of modern CME is to get to level 4 outcomes with its educational activities, but achieving this goal will probably require not only the implementation of level 2 and 3 evaluations, but also the development of new educational methods that measure or accurately predict level 4 behaviors, as such methods are currently not widely accepted, practical, or affordable. In the meantime, there is much that can be done to improve the current state of the art and to design programs to achieve higher levels of outcome than simple exposure to information.

Recommendations from the authors: can you get there from here?

Facilitating learning that leads to behavioral changes and skills development via educational programs for adults is an emerging science often applied best in the corporate world and only now beginning to be applied as well in the design of CME activities (15, 18–21, 23, 25, 29–32). Targeting learning as well as behavioral changes as the desired outcomes of psychopharmacology CME activities requires the utilization of modern principles of adult education with an emphasis on the design of the program as much as upon the actual content of the program (20, 21, 25, 29, 30). This also requires building in assessments of learning and of changes in attitude and exercises that have the potential to predict new behaviors in the real-world setting, especially case-based exercises (25, 26).

Educational programs in medicine have traditionally had a content focus: new or changed data, procedures, tests, and treatments. When content is king, educational programs are designed by choosing the best content and then packing this into an educational activity. In addition, when content is king, then presenters are the nobility. Given CME programs for which the highest priority is to provide good content and a lot of it, the second priority generally is to have the content organized and designed by the best names in the field and in a manner that is best for the presenter (i.e., convenient for the presenter, familiar to the presenter, designed for how the presenter best likes to teach, representative of how the presenter learns best, and so on) with the assumption that the goal is for the presenter to understand the content. In this traditional scenario, the participant is thus the pawn and has the lowest priority focus. In other words, great content delivered by a high-profile expert should be sufficient for any medical audience, and the members of the audience should be able to figure out for themselves how to take the recommendations of the expert and follow the logic of the data.

Changing the focus to the participant

Modern principles of educational design suggest that a palace coup is in order to change the focus of traditional medical education from the content and the expert to the participant. Instead of asking only what content is the most important to include, who is the presenter, and what design is best for the presenter, the idea now is to focus on the participant and to do this by beginning with the end in mind. If the end goal is to change a specific behavior of the participant, to shift a specific attitude of the participant, or to impart a certain set of facts that must be mastered by the participant, then the content is chosen and the delivery of that content is designed with these participant-focused outcomes as the priority (18–21, 25, 29–32).

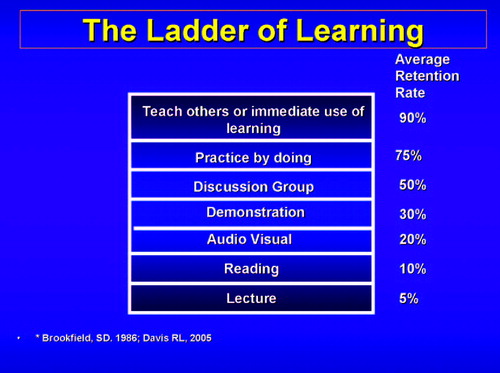

For example, participants may learn in a manner that may be entirely different from the manner in which speakers like to deliver content. The “ladder of learning” (Figure 5) (21, 25) suggests that retention of new material 72 hours after exposure is very low for lectures. Yet the lecture format is the most frequently used teaching vehicle, perhaps because it fits the traditional education model of content focus, allowing the most content exposure in the shortest period of time, as well as speaker focus, using an educational vehicle that is most convenient for the speaker.

However, if the outcome is retention of information rather than exposure to information, a shift in paradigm is in order. Therefore, if 100 facts are delivered efficiently by the speaker in a lecture, which results inefficiently in only 10%–20% retention (i.e., 10 or 20 facts remembered), is this better than exposing the participant, perhaps with more preparation time by the speaker and certainly with a reduction in exposure to content, to a demonstration or discussion of half the content (50 facts) with 70% retention (or 35 facts remembered)?

Thus, it seems that the least efficient content delivery method for the participant is the most frequently used in most CME programs (Figure 5). Because learning is rarely measured in CME activities, retention of new information is not a usual outcome that is assessed and thus the negative consequences to learning of a content-focused activity rather than a participant-focused activity are not detected. Also, because CME activities are not participant-focused, the more effective methods for facilitating learning (Figure 5), such as demonstrations, discussion groups, practice by doing, and immediate use of learning, are not incorporated into the content delivery. These methods tend to take a great deal of preparation time that may be inconvenient to the presenter and require facilitation skills, which many medical presenters may lack, rather than lecturing skills. In addition, changes in the layout of rooms are required to provide space for discussions and peer-to-peer interactions, as well as a paradigm shift from traditional medical education. Such elements can present great barriers to implementation and may be why these educational techniques are so rarely used despite their enhanced ability to facilitate learning and retention of new material. Nevertheless, it may now be the time to consider these methods of presenting content if learning is a desired outcome.

Other issues of educational design involve repetition, interactivity, significant emotional events, provoking questions, stimulating the search for the answer, and the chance for both reflective and participative activities (17–21,29). Most learners are visual learners, but most activities consist of written and spoken words. Animations and case visualizations are powerful visual means of communication but take skill and resources to prepare. Personality styles are variable in any given audience, and these influence how participants learn, yet they are rarely taken into account in the design of CME activities (31, 33). The bottom line is that designers of psychopharmacology CME can and should tap into a rich array of educational design features that have the potential not only to facilitate learning, but also to create the opportunity to maximize the chances that such learning can transfer into clinical practice to improve the outcomes of patients.

Figure 1. Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Evaluation

(Used with permission, copyright Neuroscience Education Institute 2006.)

Figure 2. Documentation of Learning

Pretest = light color; posttest = dark color. N = 497. Question from Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharmacology Academy, New York, July 2006. (Used with permission, copyright Neuroscience Education Institute 2006.)

Figure 3. Use of a Case Vignette to Demonstrate a Transfer from Knowledge to a Change in Prescribing Behavior at the End of a CME Activity

A) Precourse, N = 297. B) Postcourse, N = 297. Questions from Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharmacology Academy, San Francisco, June, 2006. (Used with permission, copyright Neuroscience Education Institute 2006.)

Figure 4. Intent to Change Behavior in Clinical Practice After a CME activity

Light color = pretest; dark color = posttest. N = 297. Questions from Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharmacology Academy, San Francisco, June, 2006. (Used with permission, copyright Neuroscience Education Institute 2006.)

Figure 5. The Ladder of Learning (20, 26)

(Used with permission, copyright Neuroscience Education Institute 2006.)

CME Disclosure Stephen M. Stahl, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego. Grant/Research Support: Asahi Kasei Pharma, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Meyers, Squibb, Cephalon, Cypress Biosciences, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Shire, Sepracor, Wythe. Consultant: Asahi Kasei Pharma, AstraZenica Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Meyers, Squibb Company, Cephalon, Cyberonics, Cypress Biosciences, Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmith Kline, Janssen, NovaDel Pharma, Oragnon, Otsuka American Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Sepracor, Shire, Solvay, Wyeth. Meghan Grady, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego. No significant financial conflict of interest or affiliation to report. Gerardeen Santiago, Ph.D., Neuroscience Education Institute, Carlsbad, CA. No significant financial conflict of interest or affiliation to report. Richard L. Davis, Arbor Scientia, Carlsbad, CA. No significant financial conflict of interest or affiliation to report.

1 Tu K, Davis D: Can we alter physician behavior by educational methods? Lessons learned from studies of the management and followup of hypertension. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2002; 22:11–22Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Maynes RB: Evidence for the effectiveness of CME: a review of 50 randomized controlled trials. JAMA 1992; 268:1111–1117Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB: Changing physician performance: a systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 1995; 274:700–705Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Davis DA, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf RM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A: Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA 1999; 282: 867–874Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Fox RD, Bennett NL: Learning and change: implications for continuing medical education, BMJ 1998; 316:466–468Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB: No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ 1995; 153:1423–1431Google Scholar

7 Hodges B, Inch C, Silver I: Improving the psychiatric knowledge, skills and attitudes of primary care physicians, 1950–2000: a review. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1579–1586Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Kroenke K, Taylor-Vaisey A, Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE: Interventions to improve provider diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care: a critical review of the literature. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:39–52Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Stahl SM: It takes two to entangle: separating medical education from pharmaceutical promotion. PsychEd Up 2005; 1:6–7 issue 3Google Scholar

10 Stahl SM: Detecting and dealing with bias in psychopharmacology: bias in psychopharmacology can be easily detected and may be useful in evaluating whether to use different agents. PsychEd Up 2005; 1:6–7 issue 4Google Scholar

11 Wazana A: Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA 2000; 283:373–380Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Relman AS: Separating continuing medical education from pharmaceutical marketing. JAMA 2001; 285:2009–2012Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Relman AS: Defending professional independence: ACCME’s proposed new guidelines for commercial support of CME. JAMA 2003; 289:2418–2420Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Geertsma R, Parker RC, Whitbourne SK: How physicians view the process of change in their practice behavior. J Med Educ 1982; 57:752–761Google Scholar

15 Mazmanian PE: Reform of continuing medical education in the United States J Contin Educ Health Prof 2005; 25:132–133Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Davis D: Continuing education, guideline implementation, and the emerging transdisciplinary field of knowledge translation. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006; 26:5–12Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Kirkpatrick D: Evaluating Training Programs. San Francisco, Berrett-Koehler, 1994Google Scholar

18 Miller RG, Ashar BH, Getz KJ: Evaluation of an audience response system for the continuing education of health professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2003; 23:109–116Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Fox RD, Mazmanian PE, Putman RW: Changing and Learning in the Lives of Physicians. New York, Praeger, 1989Google Scholar

20 Prochaska JO, Velicer WF: The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997; 12:38–48Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Gagne RM: The Conditions of Learning and Theory of Instruction, 4th ed. New York, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1985Google Scholar

22 Brookfield SD: Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1986Google Scholar

23 Sharma S, Chadda RK, Rishi RK, Gulati RK, Bapna JS: Prescribing pattern and indicators for performance in a psychiatric practice. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2003; 7:231–238Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Davis N: Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes (Cochrane review). J Contin Educ Health Prof 2001; 21:187–191Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Jain S, Hansen J, Spell M, Lee M: Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: a prospective validation study. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:771–780Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M: Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 2000; 283: 1715–1722Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Davis RL: Enlightened education: preventing audience abuse. PsychEd Up 2005; 1:5Google Scholar

28 Wakefield J, Herbert CP, Maclure M, Dormuth C, Wright JM, Legare J, Brett-MacLean P, Premi J: Commitment to change statements can predict actual change in practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2003; 23:81–93Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Delcourt JL: Commitment to change: a strategy for promoting educational effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2000; 20:156–163Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Bligh DA: What’s the Use of Lectures? San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2000Google Scholar

31 Stahl SM: The 7 habits of highly effective psychopharmacologists. Part 3: Sharpen the saw with selective choices of continuing medical education programs. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:401–402Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Pratt DD, Arseneau R, Collins JB: Reconsidering “good teaching” across the continuum of medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2001; 21:70–81Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Armstrong E, Parsa-Parsi R: How can physicians’ learning styles drive educational planning. Acad Med 2005; 80:680–684Crossref, Google Scholar