Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic, disabling disorder that affects 8%–9% of the population at some point in their lifetime. The disorder is associated with significant morbidity and functional impairment, affecting both patients and family members, and its costs are similar to those of other severe mental disorders. The pathophysiology of PTSD involves a complex interplay between trauma-related factors and the neurobiological and psychosocial influences that determine individual differences in resilience and vulnerability. Despite its wide prevalence, PTSD remains an underrecognized disorder, with proper diagnosis complicated by a variety of factors, including stigma, comorbidity and symptom overlap, and high diagnostic thresholds. Through careful assessment of trauma and PTSD in all patients, health care providers may more readily identify individuals at risk of PTSD and in need of interventions early on, thereby improving outcome and potentially limiting the chronic and disabling course of the illness. Recent research demonstrates efficacy for both pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions in treating PTSD. First-line pharmacotherapeutic options are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Among the most effective psychosocial interventions are cognitive behavioral approaches that use exposure and cognitive restructuring techniques.

Over the past century and a half, posttraumatic syndromes have been reported in the medical literature under a variety of names, including railway spine, war neurosis, shell shock, soldier’s heart, combat fatigue, and rape-trauma syndrome. It was not until 1980, however, with the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (1), that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) first appeared among the anxiety disorders in the DSM classification. Today we recognize that PTSD is a common disorder, ranking as the second most prevalent anxiety condition in the United States, after social anxiety disorder (2). PTSD tends to be a chronic, disabling disorder and is associated with high rates of comorbidity, social and occupational impairment, and health care costs, comparable to those of other severe mental illnesses. Estimates suggest that with the increasing rates of trauma worldwide, PTSD is on track to become a major global public health problem.

In this article, we review the current knowledge about PTSD, beginning with a definition and discussion of the epidemiology and illness course. An examination of the neurobiological, psychological, and social factors that affect the development of PTSD follows. We then discuss the assessment of trauma and PTSD and review treatment outcome data, focusing on developments reported in the past 5 years. We conclude with a brief discussion of the limitations of our current understanding of PTSD and possible directions for future research.

Definition

PTSD is distinct from other psychiatric disorders in its requirement for exposure to an external, traumatic stressor. As defined in DSM-IV, this is an event that involves life endangerment, death, or serious injury or threat and is accompanied by feelings of intense fear, horror, or helplessness. Individuals who experience a trauma of this nature may develop symptoms that fall into three distinct clusters: reexperiencing phenomenon; avoidance and numbing; and autonomic hyperarousal. The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Table 1) require that a minimum number of symptoms from each cluster be present (one or more reexperiencing symptoms; three or more avoidance/numbing symptoms; two or more hyperarousal symptoms) and that they coexist for at least 1 month after the trauma and are associated with significant distress or functional impairment (3). Symptoms that have been present for 1 to 3 months are termed acute, whereas those that persist beyond 3 months are considered chronic. The development of symptoms 6 months or more after the trauma is termed delayed onset. Similar criteria have been set forth by the World Health Organization (4), although the WHO criteria place less emphasis on emotional numbing and require evidence that symptoms arose within 6 months of the trauma.

Epidemiology and natural history

Prevalence of trauma and PTSD

Epidemiologic studies reveal that traumatic events are common. The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) reported a lifetime history of at least one traumatic event for 61% of men and 51% of women, with many individuals (25%–50%) experiencing two or more traumas (5). Similar figures have been reported in other community-based samples (43%–92% for men; 37%–87% for women) (5–8). The most common types of trauma reported are witnessing someone being injured or killed, being involved in a natural disaster, and being involved in a life-threatening accident. Beyond these events, men and women tend to experience different types of traumatic exposure, with men more likely to experience being threatened with a weapon, being held captive or kidnapped, physical assault, and combat. In contrast, women more commonly experience rape and sexual molestation (9).

Prevalence estimates vary with the diagnostic criteria applied, the sample studied, and the assessment procedures used. Early estimates derived from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey, using DSM-III criteria, revealed a lifetime prevalence of 1.0%–1.3% (10, 11). More recent U.S. population-based estimates, using DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria, reveal a lifetime prevalence of 8%–9% (6, 9). Although community prevalence estimates in developing nations are lacking, we can expect PTSD to be more prevalent in countries where exposure to trauma, particularly in the form of interpersonal violence, is more likely.

The prevalence of PTSD in treatment-seeking populations can be considerable. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among primary care patients has been estimated at 12%–39% (12, 13), and rates are higher among individuals who have been exposed to mass trauma, such as U.S. citizens 2 months after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks (17%) (14), the Oklahoma City community after the terrorist bombing in 1995 (34%) (15), Bosnian refugees (65%) (16), and Palestinian children exposed to war trauma (73%) (17).

Rates of PTSD are consistently higher among women, as reported both in the general community (5% among men and 10% among women) and in trauma-exposed groups (8% among men and 20% among women) (8, 9). Potential explanations for this gender difference include the higher prevalence of violent sexual trauma among women as well as their greater vulnerability to depression (18) and lower rates of serotonin synthesis (19).

Posttraumatic symptoms that do not meet the threshold for a diagnosis of PTSD may be accompanied by significant impairment, a condition referred to as partial or subthreshold PTSD. The 1-month prevalence of partial PTSD has been estimated at 3.4% for women and 0.3% for men (5), with higher rates reported for psychiatric outpatients and trauma cohorts (20–22). The occupational and social impairment observed in partial PTSD rival those reported with full PTSD (5, 20, 21), yet most individuals with partial PTSD remain untreated.

Acute stress disorder may occur among individuals who experience severe reactions to traumatic events, placing them at risk of developing PTSD in the following month. The symptom criteria for acute stress disorder include one or more dissociative symptoms, one or more intrusive symptoms, marked avoidance, and hyperarousal. These symptoms are associated with clinically significant distress and impairment and last from 2 days to 1 month. Symptoms usually appear within the first 24 hours after the trauma, although they may develop at any time during the month following the trauma (3). When acute stress disorder was introduced into the DSM nosology in 1994, some considered the diagnosis controversial (23); however, subsequent research has strengthened its validity (24, 25). The presence of acute stress symptoms is a strong predictor of PTSD up to 2 years after experience of a trauma (26, 27).

The course of PTSD

The course of PTSD varies among individuals after different traumatic events. Initial symptoms following a traumatic stressor may include anxiety, depression, agitation, shock, conversion, and dissociation. Within days, these responses are usually replaced by symptoms resembling PTSD and depression. The longitudinal course of PTSD has been prospectively evaluated in survivors of rape trauma and nonsexual criminal assault (28). One week after the trauma, 94% of rape victims met symptom criteria for PTSD, compared with 65% with full PTSD 1 month afterward and 47% 3 months afterward; the latter figure remained essentially unchanged over the next 6 months. In contrast, among assault victims, 65% had PTSD symptoms 2 weeks after the trauma, and 37% had full PTSD 1 month afterward. PTSD continued in 15% at 3 months, and in all of these cases it resolved over the next 6 months. These findings are consistent with those of other studies indicating that when the condition persisted 6–12 months after the trauma, PTSD tended to become chronic (29–31). Factors that are associated with chronicity include the presence of a greater number of PTSD symptoms, higher rates of numbing and reactivity, presence of anxiety or affective disorders, coexisting medical disorders, female gender, a family history of antisocial behavior, presence of alcohol abuse, and a history of childhood trauma (32, 33).

Epidemiologic studies have also provided evidence of PTSD’s chronicity. The NCS found that most improvement in PTSD symptoms occurred within the first year after the trauma, independent of treatment. After 1 year, treatment for any mental problem was associated with a significantly better outcome. After 6 years, however, about one-third of those with PTSD did not remit, regardless of treatment (9). On average, individuals with PTSD experience 3.3 episodes—periods during which the individual is symptomatic and meets criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD—during their lifetime, with each episode lasting about 7 years, suggesting that active symptoms are typically present for more than 20 years overall (8, 34).

In the most severe instances, a complex clinical picture with overlapping symptoms of PTSD and borderline personality disorder may develop. This condition, known as complex PTSD (or, in DSM-IV, disorder of extreme stress, not otherwise specified) is associated with prolonged exposure to overwhelming interpersonal stress (e.g., childhood sexual or physical abuse) and integrates symptoms of affective dysregulation, dissociation, somatization, and altered perceptions of self and others (35, 36). A recent study found that among adult women, those who experienced early childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse and paternal incest, were more likely to have diagnoses of complex PTSD and borderline personality disorder than those for whom abuse began after age 12 (37). Although some suggest that the construct of complex PTSD oversimplifies the intricacies of borderline personality dynamics (38), complex PTSD encompasses the mixture of axis I “state” and axis II “trait” symptoms and provides a way to classify individuals under a single diagnosis.

Health and psychosocial consequences

High rates of psychiatric and medical comorbidity occur with PTSD and can complicate diagnosis. It is estimated that 88% of men and 79% of women with PTSD have a lifetime history of another psychiatric disorder (9), particularly major depression (about 50%), dysthymia (<20%), and an anxiety disorder (25%), especially simple phobia and social phobia. Comorbid substance use disorders and conduct disorder are also common, with higher rates observed in men (alcohol, 52% in men and 29% in women; other substances, 35% and 27%; conduct disorder, 43% and 15%) (9). Psychotic symptoms may occur in 30%–40% of individuals with PTSD and may approach the severity observed in schizophrenia (39, 40). Suicide risk is high among individuals with PTSD, with suicide attempts occurring as much as six times more often than they do in the general population. The association between suicidality and PTSD is stronger than it is with other anxiety disorders, but less than it is with major depression (41).

Other adverse health effects observed in PTSD are demonstrated through high lifetime rates of circulatory, respiratory, digestive, dermatologic, musculoskeletal, neurologic, ophthalmologic, endocrinologic, and gynecologic disorders, nonsexually transmitted infectious diseases, medically explained and unexplained somatic symptoms, pain, risky sexual behavior, and eating disorders (42–47). These findings suggest that trauma and PTSD may have systemic effects over time, with PTSD mediating a relationship between trauma and physical health. This hypothesis is supported by the various neurobiological abnormalities (e.g., immunologic and endocrinologic) and psychological factors (e.g., hostility, depression, and negative health behaviors) that are seen in patients with PTSD.

Trauma and PTSD are major public health issues that have personal and societal impacts on a par with those of major depression. The disabling consequences of PTSD are evident in the related personal, social, and occupational impairment of those with the disorder (48–50). PTSD accounts for much of the $42 billion (1997) cost of anxiety disorders annually, owing to both the direct costs of medical care and the indirect costs of lost productivity (51), including an average work loss of 3.6 days per month (34). International health trends suggest that over the next 20 years, trauma-related conditions (e.g., road traffic accidents, war injuries, and depression) will have a significant impact on the global burden of illness and will be among the leading causes of disease burden worldwide (52).

Biopsychosocial underpinnings of PTSD

PTSD is the only psychiatric disorder for which an external stressor is a diagnostic criterion. This point illustrates the complex interplay between external factors inherent in the trauma itself and the biological, psychological, and social factors related to the development of PTSD.

Psychological models of PTSD

Psychological models propose that the mechanisms observed in fear conditioning, extinction, and sensitization are all relevant in PTSD (53). Animal models of stress exposure liken PTSD to a conditioned fear response (54). An animal exposed to a neutral stimulus (e.g., a buzzer) paired with a shock will demonstrate, over time, heightened physiologic reactivity when exposed to the buzzer alone. The buzzer then becomes a conditioned stimulus and the response a conditioned fear response. In people with PTSD, a trauma-related stimulus is a trigger that evokes fear-conditioned PTSD symptoms. For example, if a woman is assaulted in her car, the car can become a conditioned stimulus or trigger that evokes a conditioned fear response. Similarly, sights, sounds, or smells experienced during the assault may become conditioned triggers of reexperiencing symptoms. This paradigm is central to current cognitive behavioral treatments that target the conditioned fear response.

Psychosocial influences

The type and intensity of the trauma (i.e., duration, degree of exposure, extent of injury or threat to life) affect the development of PTSD. Assaultive violence is associated with the highest rates of PTSD (21%), and the sudden death of a loved one is the experience most often reported as the precipitating event among persons with PTSD (31% of PTSD cases, with a risk of 14%) (8). Among former prisoners of war, the severity of trauma during captivity was the best predictor of current PTSD symptoms (55). Trauma-related factors, such as proximity to the trauma, loss of possessions, and involvement in rescue efforts, were found to be risk factors for PTSD after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack in New York City (56). Trauma-related symptoms, such as peritraumatic dissociation and early symptoms of heightened arousal and coping with disengagement, may also be predictors of PTSD and illness severity (57, 58).

Several demographic and personal characteristics are linked to either a heightened risk of PTSD or a resilience to PTSD. Recent research findings highlight the association between female gender and risk of PTSD, independent of trauma severity and perceived threat to life (59, 60). Other personal characteristics that are associated with a heightened risk of PTSD include low income, poor education, minority status, high life stress, history of childhood abuse (particularly sexual assault before age 16), history of psychiatric illness, family history of anxiety and antisocial personality disorder, history of childhood adversity (e.g., early separation from parents, parental separation or divorce, and poverty), sense of lack of personal control, feelings of insecurity, and alienation from others (10, 14, 61–63).

The transgenerational effects of PTSD in families are also noted in the literature. Parental PTSD is a risk factor for PTSD in adult children of Holocaust survivors, reflecting the effects of both psychosocial and familial influences (64). Among Vietnam veterans, having experienced negative parenting is more predictive of PTSD than the level of combat trauma exposure (65). PTSD can also affect parenting, with high lifetime rates of PTSD reported in the mothers of severely maltreated children (66), and is linked to child behavior problems and marital discord (67).

Severe loss, particularly parental loss, and the absence of care (e.g., parental or caregiver absence and neglect) may be as predictive of psychological distress in children as are events that are more frequently studied, such as sexual and physical abuse (68). Unresolved loss may lead to a failure to integrate representations of self and the world (69).

The presence of social support after trauma is a protective factor against PTSD (70, 71). Among women who experienced interpersonal violence, higher social support was associated with a lower risk of poor mental health (71). Among rape trauma survivors, those who experienced supportive social reactions to the trauma had fewer emotional and physical health problems than did those who perceived social reactions to be hurtful (72). In contrast, poor social support is a risk factor for PTSD in studies of medically ill persons (e.g., after myocardial infarction or bone marrow transplantation) (73, 74).

Neurobiology of PTSD

The stress response is dysregulated in PTSD and influenced by neurochemical and neuroanatomic abnormalities and genetic vulnerabilities. Persistent alterations have been observed in physiologic reactivity and levels of specific stress-responsive neurochemicals. Neuroanatomic changes have also been reported. Findings from family and twin studies suggest a genetic vulnerability to PTSD. Recent findings in these areas are reviewed below.

The HPA axis.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis appears to be dysregulated in individuals with PTSD (75), although the direction of the abnormality is unclear. Some studies report elevated cortisol levels, whereas others note low or normal levels (76, 77). Methodological and population differences across studies may account for these discrepancies. There have been reports of low cortisol levels (78) and heightened responsiveness to corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) (76, 79), raising the possibility that low cortisol levels prior to traumatic stress exposure elevate the risk of PTSD. There may also be gender differences in HPA axis activity in PTSD (80), with heightened ACTH activity and adrenal cortisol response to CRF reported in women with PTSD compared with controls (79). These results differ from earlier reports of low cortisol levels and blunted ACTH responses to CRF in men with PTSD (81).

Catecholamines.

Catecholaminergic activity increases during stress, and research findings suggest that catecholaminergic dysfunction, especially in norepinephrine, may play a role in the development of specific PTSD symptoms. On exposure to stress, norepinephrine is rapidly released from the locus ceruleus, leading to elevations in heart rate and blood pressure and symptoms of increased arousal. Stress paradigms demonstrate increased noradrenergic and sympathetic activity in PTSD (82, 83), and this hyperactivity may contribute to the core autonomic hyperarousal and reexperiencing symptoms. There may also be a relationship between increased norepinephrine activity and enhanced long-term memory for traumatic events and PTSD reexperiencing symptoms (84, 85).

Serotonin.

Converging evidence supports a role for serotonergic dysregulation in PTSD. Platelet paroxetine binding (a peripheral marker of serotonergic function) is lower in individuals with PTSD and may be a predictor of response to treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (86–88). d-Fenfluramine, a serotonin-releasing agent and reuptake inhibitor, was used to assess the integrity of the serotonergic system in PTSD through prompting of serotonin-mediated prolactin release. A low prolactin response to D-fenfluramine was observed in veterans with PTSD, and this response was inversely correlated with severity of PTSD symptoms and aggression (89). Serotonin dysregulation is linked to specific PTSD symptoms, including aggression, impulsivity, depression, and suicidality (90). The clinical efficacy of the SSRIs in the treatment of PTSD lends additional support to a role for serotonin in PTSD (91, 92).

Dopamine.

Dopamine is involved in control of locomotion, cognition, affect, and neuroendocrine secretion. Preclinical studies demonstrate that the mesocortical/mesoprefrontal and mesolimbic systems appear to be the dopaminergic neuronal systems most vulnerable to the influences of stress (93, 94). Clinical findings that support a role for dopamine in the stress response and in PTSD include the high rates of psychotic symptoms observed among individuals with PTSD (39) and the abnormally high concentrations of urinary dopamine (in addition to cortisol and norepinephrine) in children with PTSD after years of severe maltreatment (95). Genetically determined changes in dopaminergic reactivity also may contribute to the risk of PTSD (96, 97).

Central amino acids.

Excitatory glutaminergic and inhibitory GABA-ergic (γ-aminobutyric acid) pathways are implicated in encoding memory and may play a role in the pathophysiology of PTSD. Glutaminergic mechanisms are central to neuronal activation and cognitive functions, such as perception, appraisal, conditioning, extinction, and memory, all of which may be altered in PTSD (53). A role for GABA is suggested in findings of a reduction in peripheral and central benzodiazepine receptors in subjects with PTSD (98–100), which may reflect an adaptive response to an overproduction of glucocorticoids in hyperarousal states. Consistent with this hypothesis are the elevated plasma levels of the GABA(A) antagonistic neuro-steroid dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in individuals with PTSD (101).

Opioids.

Opioid system dysfunction is seen in the avoidance/numbing and hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD. Normally, stress-induced opioid activity inhibits both the HPA and norepinephrine systems, thus promoting recovery. In PTSD, abnormal levels of endogenous opioids and lower pain thresholds have been reported (102), suggesting a potential therapeutic role for opioid antagonists.

Immune system.

Exposure to trauma can result in immune dysregulation, implicating the immune system in PTSD pathophysiology. Cytokine profiles in PTSD are similar to those observed in clinical chronic psychological stress models, although differences are noted in other immune parameters (103). It remains unclear whether these changes are central or peripheral to the pathophysiology of PTSD. Investigations of the role of the immune system are also challenged by the inconsistent findings across studies.

Brain structure and function.

Persons with PTSD may have alterations in brain regions central to the neurobiological fear response, specifically, the amygdala and the hippocampus. These structures are components of the limbic system, the area of the brain involved in the regulation of emotions, memory, and fear. The amygdala plays a role in threat assessment, fear conditioning, and emotional learning, and the hippocampus is implicated in learning, memory consolidation, and contextual processing. PTSD can be likened to a conditioned fear response, whereby an extreme threat becomes paired with a constellation of situational triggers, resulting in an abnormal fear response.

Recent research has focused on the role of specific CNS regions in the development of PTSD, although findings from neuroimaging studies to date are inconclusive. Findings of reduced hippocampal volumes have been reported in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies (104–106), although this result is somewhat controversial, with conflicting findings published (107–109). Neuroimaging evidence also suggests decreased hippocampal function (110), and flashback intensity has been linked to cerebral blood flow in this region (111). The amygdala has been implicated in PTSD in findings from MRI and single photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) studies (112, 113). Functional MRI studies demonstrate alterations in other CNS regions in PTSD, including the anterior cingulate gyrus, the thalamus, and the medial frontal cortex (114–116). Discrepancies in the neuroimaging literature may be explained by methodological differences across studies.

Genetic factors.

Data from both preclinical research and family and twin studies implicate a genetic contribution to the development of PTSD (117). Animals that are genetically predisposed to learned helplessness demonstrate cognitive deficits, analgesia, and HPA axis hyporesponsiveness in ways similar to those seen in people with PTSD (118). A recent review of family and twin studies provides evidence to support a role for familial influences in the development of PTSD (119). However, it remains unclear what vulnerabilities are inherited and how these may interact with the trauma experienced. Future research may focus on trait markers such as HPA axis hypofunction, increased arousal, and increased acoustic startle response (120, 121).

Assessment

Despite its high prevalence, PTSD remains an underrecognized disorder. Proper identification of those at risk is complicated by a number of factors. Individuals may be reluctant to seek treatment because of the stigma associated with trauma and mental illness, feelings of guilt and discomfort, or fear of reprisal to self or loved ones, particularly if the trauma is recent or ongoing. Health care providers often fail to inquire about trauma, largely owing to time constraints or personal discomfort with the topic or because they do not know how to inquire about trauma. Other complicating factors include the high diagnostic threshold for the disorder and high rates of comorbidity and symptom overlap with other mental illnesses.

Screening for trauma exposure is the first step in PTSD assessment. It is important to obtain a longitudinal history, including evaluation of traumatic experiences throughout the person’s life and for each event assessing the following: age at the time of trauma; duration of trauma (single, recurrent, or ongoing); type of trauma; if interpersonal, relationship to the perpetrator; and response and perceived impact of the event. This information should be elicited at the initial evaluation and updated at periodic intervals during the course of treatment. Several brief scales have been developed to collect history related to general trauma exposure (122, 123) as well as to specific traumatic experiences, such as sexual abuse (124). A more extensive trauma history can be obtained at follow-up, ideally in a quiet, private setting where the clinician can support the patient in discussing these distressing experiences.

Evaluation for PTSD includes assessment of each symptom cluster—reexperiencing, avoidance and numbing, and hyperarousal. Several psychometrically validated scales have been developed to facilitate this process. Although not a substitute for a clinical interview, rating scales can enhance clinical practice in several ways. They can identify patients at high risk of PTSD, they can be used to confirm the diagnosis, assess illness severity, identify target symptoms, monitor treatment outcome, and provide patient education, and they can serve as a source of documentation.

A variety of self-rated and observer-based scales are used in evaluating PTSD symptoms. Several brief screening instruments have been developed and validated (125–127) to facilitate PTSD recognition. These instruments are particularly useful in primary care and mass trauma situations, where they help identify those who need a focused clinical evaluation. More detailed symptom screening instruments that assess the full range of PTSD symptoms, including symptom frequency, severity, and related distress and impairment, may be helpful in psychiatric practice. Several validated, self-rated measures include the PTSD Checklist (128, 129), Impact of Event Scale–Revised (130), and the Davidson Trauma Scale (131). Structured diagnostic interviews are used in clinical research, where they are considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of PTSD. Two of the most widely used scales in this category are the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (132) and the Structured Interview for PTSD (133). A useful tool for interval symptom assessment during treatment is the Short PTSD Rating Interview (134), which also assesses somatic malaise, work and social functioning, and global performance.

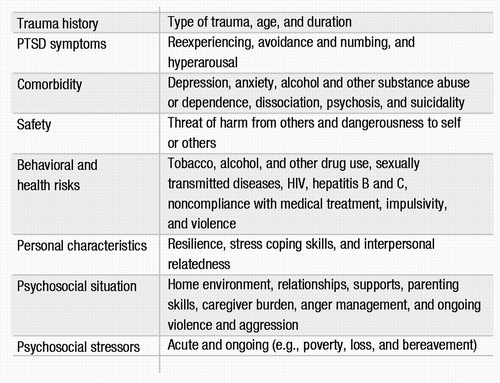

Other clinically relevant domains to be considered in a PTSD assessment are listed in Table 2. The effects of PTSD carry over to other areas of functioning, with high rates of comorbidity and symptom overlap. The presence of comorbid disorders affects both diagnosis and treatment and needs to be identified early in the assessment. Patient safety is a crucial concern. Clinicians should evaluate the threat of harm by others to the patient and family members, such as in the setting of incest or domestic violence. Dangerousness to self and others should also be evaluated, given the risk of aggression, impulsivity, and suicidal behavior in this population (41, 135). Psychosocial influences and high-risk health behaviors can have a significant impact on current and long-term functioning and also need to be considered. A thorough evaluation of social supports is extremely important, because the presence of supports is a predictor of better outcome (136, 137). It is also important to place the assessment in the context of acute and ongoing stressors in the individual’s life. Compared with other anxiety disorders, PTSD is associated with lower levels of stress coping (unpublished 2002 study by K. M. Connor and J. R. T. Davidson), which may compromise a person’s ability to handle the stresses of daily life.

Treatment

In treating patients with PTSD, five goals should be considered: reducing the severity of the core symptoms of the disorder, strengthening resilience and coping, reducing comorbidity, reducing disability, and improving quality of life. Research on treatment of PTSD has yielded promising results for both pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions. The issue of combined medication and psychosocial treatment modalities, however, remains largely unstudied.

Pharmacotherapy

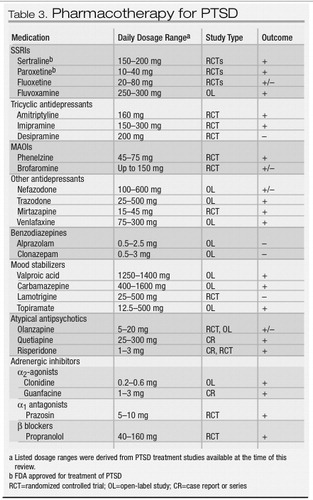

With these treatment goals in mind, a variety of pharmacologic agents can be effective for PTSD (Table 3). The SSRIs are considered first-line pharmacotherapy on the basis of data from randomized controlled trials and side effect profiles. The tricyclic antidepressants and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are also effective, although they are less well tolerated and more difficult to prescribe because of side effects, required dietary restrictions to prevent hypertensive crises, and potential lethality in overdose. Although benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, adrenergic agents, and atypical antipsychotics may have a role in treating certain symptoms, there is a lack of controlled trial data supporting their use in this capacity.

SSRIs.

Evidence from several large randomized, double-blind controlled trials indicate that SSRIs are the first line of treatment for both men and women (92, 138–143). In these trials, fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine were all shown to have efficacy in reducing the severity of the core symptoms of PTSD and improving quality of life. Study subjects were predominantly women with chronic PTSD related to assault or rape. The trials were of relatively short duration (8–12 weeks), particularly given the chronicity of the disorder. Reductions in the severity of core PTSD symptoms are usually seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment; for anger/irritability symptoms improvement may been seen as early as the first week (144). Relapse prevention trials of 6–9 months’ duration suggest that continued treatment with SSRIs can prevent relapse and provide further improvement in PTSD symptoms, comorbid depression, and quality of life (139, 145).

There may be differences in core symptom response for the various SSRIs. For example, fluoxetine rendered marked improvement in arousal and numbing symptoms and was more effective in women than in men in two of three studies (142, 143, 146). In one large, multicenter controlled trial of sertraline, improvement was found in avoidance/numbing and arousal symptoms, but not for reexperiencing, with a more robust overall response noted in women (147). Subsequent multicenter controlled trials, however, demonstrated efficacy for sertraline and paroxetine for all three symptom clusters in both genders, and both drugs received FDA approval for the treatment of PTSD.

Fluvoxamine was studied in two small open-label trials with outpatients with combat-related PTSD (148, 149). Preliminary results suggest possible efficacy for sleep-related symptoms, including nightmares.

Tricyclics and MAOIs.

Early trials of tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs were conducted primarily with male combat veterans, and results suggested efficacy for PTSD. Among the tricyclics, amitriptyline and imipramine demonstrated efficacy in reducing core PTSD symptoms (150, 151), but desipramine did not (152). To our knowledge, there have been no controlled trials of tricyclics in women with PTSD. Given the evidence for noradrenergic dysregulation in PTSD and the poor response of some patients to SSRIs, such research is warranted. Studies of MAOIs have suggested efficacy for phenelzine (150, 153) and possibly brofaromine (a reversible MAOI available in Europe) (154, 155).

Other antidepressants.

Findings from recent studies have suggested that mirtazapine, trazodone, nefazodone, and venlafaxine may have a role in PTSD treatment. Mirtazapine, a novel drug with both noradrenergic and serotonergic properties, demonstrated efficacy in an open-label study and one 8-week controlled trial (156, 157). Preliminary data from a small open-label study suggest that trazodone may be effective in reducing the core PTSD symptoms in combat veterans (158). Of more than 100 patients with chronic PTSD enrolled in six open-label trials of nefazodone, nearly half reported some improvement in symptoms (159). Two controlled trials with nefazodone were completed, although to our knowledge the results have not been published. Evidence from case reports and case series suggests that venlafaxine also may be effective in the treatment of PTSD, and multicenter controlled trials are under way (160, 161).

Benzodiazepines.

Benzodiazepines can reduce anxiety and improve sleep but may also increase the likelihood of subsequent PTSD. Their use as monotherapy in this condition should therefore be considered controversial. In an open-label study, temazepam improved insomnia and PTSD symptoms over 5 nights in four subjects with acute stress reactions (162). Another study prospectively evaluated the effect of acute administration of benzodiazepines (clonazepam or alprazolam) on the course of PTSD in 13 trauma survivors compared with pair-matched controls. Early administration of benzodiazepines was not found have a beneficial effect at 1- or 6-month follow-up assessments and was actually associated with a higher incidence of PTSD (163).

The addictive potential of the benzodiazepines may be problematic, given high rates of comorbid substance use disorders in PTSD. However, in a recent naturalistic study of over 300 veterans with PTSD and comorbid substance abuse, treatment with benzodiazepines was not associated with adverse effects on outcome (164). In contrast, a case series of combat veterans with PTSD reported that discontinuation of alprazolam resulted in severe withdrawal and worsening of PTSD symptoms, including rage reactions, nightmares, and homicidal ideation (165).

Mood stabilizers.

An interest in the therapeutic role of anticonvulsants developed from the recognition of the possible role of neuronal sensitization and kindling in the pathophysiology of PTSD, along with the high prevalence of impulsivity among those with the disorder. Findings from open-label studies of carbamazepine, divalproex, and topiramate and a controlled trial of lamotri-gine demonstrated mixed effects on the symptom clusters (166–170). The one consistent finding in these studies, however, was a beneficial effect on reexperiencing symptoms. Controlled trials are needed to investigate this observation.

Atypical antipsychotics.

Up to 40% of patients with PTSD may have psychotic symptoms, underscoring the potential therapeutic role for atypical antipsychotics (40). To date, preliminary studies suggest a potential role for olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. Olanzapine is the most widely studied drug in this class, and published reports yield mixed results, including a negative controlled trial with a predominantly female veteran cohort, which contrasted with symptom improvement in all clusters in an open-label study of male combat veterans (171, 172). In a recent controlled trial of adjunctive olanzapine therapy, improvement was noted in PTSD and insomnia symptoms (173). Quetiapine may hold promise in the treatment of PTSD, as suggested by findings from an open-label trial with veterans with PTSD (174). A small controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of chronic combat-related PTSD failed to demonstrate a treatment difference on the primary PTSD outcome measure, but results did support the efficacy of risperidone for treating reexperiencing and global psychotic symptoms (175). Additional research on atypical antipsychotics in PTSD is warranted.

Adrenergic-inhibiting agents.

The α2-adrenergic agonists decrease centrally mediated adrenergic activity and thus may alleviate PTSD symptoms. An open-label study of clonidine used in combination with imipramine showed some improvement in chronic PTSD in severely traumatized Cambodian refugees (176). Centrally acting α1-adrenergic antagonists are also thought to hold promise in treating PTSD symptoms. Treatment with prazosin is associated with a reduction in nightmares and improvement in PTSD symptoms in combat veterans with PTSD (177), and a case report suggests that guanfacine may be efficacious for nightmares in children (178).

The β-adrenergic blockers may reduce PTSD symptoms through a dampening of peripheral autonomic arousal. Despite the indication of β blockers for heightened arousal states, such as performance anxiety, no controlled trials of these agents have been conducted for PTSD. One naturalistic study of over 300 veterans with PTSD found that β blockers were the most frequently prescribed medications (179). Results from a recent pilot study suggest that propranolol in the immediate posttrauma period may have preventive effects on subsequent development of PTSD (180). Additional controlled studies are needed to explore this preliminary finding.

Psychosocial interventions

Psychodynamics of trauma.

Trauma dynamics can involve betrayal, abuse of power, and control. Individuals who survive childhood trauma may develop pathological attachments to perpetrators (181), and this dynamic can become amplified during psychiatric treatment. For example, residual attachment patterns or longings can be transferred onto the treating psychiatrist. Hence, careful attention to patient-provider boundaries is crucial in PTSD treatment. Contemporary trauma theory holds that clinicians should explore the personal meaning of the traumatic event and counter the demoralization that is so central to PTSD. An emphasis on the here and now is useful, as is educating the patient on the psychological features of the disorder itself.

Psychosocial treatments.

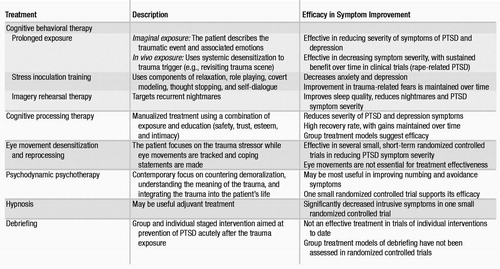

Clinicians providing psychosocial treatments should have special training in PTSD and related psychosocial interventions (Table 4). Cognitive behavioral therapies are the most extensively researched modalities, although most studies have been short-term. Exposure-based therapies and hypnosis techniques may be particularly helpful with intrusive symptoms, whereas cognitive and psychodynamically oriented treatments may be helpful with symptoms of avoidance and numbing. Psychosocial interventions should be tailored to the individual patient, with consideration given to the trauma type, the severity and type of PTSD symptoms, and the related comorbid disorders (182).

Cognitive behavioral therapies.

The purpose of cognitive behavioral therapy is to correct cognitive distortions and extinguish intrusive traumatic memories. In PTSD, cognitive behavioral therapy targets the distorted cognitions and appraisal process (183, 184), thereby desensitizing the patient to trauma-related triggers through repeated exposure. Two empirically tested modalities incorporating systematic desensitization are prolonged exposure and stress inoculation training. These treatments are effective in women with PTSD related to assaultive violence or rape. A new cognitive behavioral therapy approach, imagery rehearsal therapy, also shows promise in treating PTSD, particularly associated nightmares and insomnia (185).

Prolonged exposure was developed for rape-related PTSD in women and is an effective first-line psychosocial treatment, with sustained benefit over time in reducing PTSD symptom severity (186, 187). This treatment consists of repeated exposure to the trauma and to avoided situations, objects, and memories associated with the trauma. Exposure therapy can be imaginal or in vivo. During imaginal exposure, the patient is instructed to imagine the traumatic event and to describe it aloud with accompanying emotions. In contrast, during in vivo exposure, the patient actually revisits trauma reminders in order to achieve desensitization. Prolonged exposure is effective in decreasing PTSD symptom severity, particularly in the areas of anxiety and avoidance.

Stress inoculation training can be considered a “tool box” for managing anxiety (187). Techniques include breathing exercises, relaxation training, thought stopping, role playing, and restructuring of distorted thought patterns. Both stress inoculation training and prolonged exposure are effective, alone or in combination, in reducing chronic PTSD symptoms, although prolonged exposure may be superior (187, 188).

Imagery rehearsal therapy is a brief approach that appears to decrease chronic nightmares, improve sleep quality, and reduce overall PTSD symptom severity. In a controlled trial, rape trauma survivors showed improvement with this treatment, as have crime victims and veterans in open-label pharmacotherapy studies (185, 189).

Cognitive processing therapy.

Cognitive processing therapy was also developed for PTSD related to rape trauma (190, 191). It is designed to help correct maladaptive cognitions related to issues such as safety, with emphasis on a written narrative of the trauma. Good outcomes in a group setting format have been reported (190).

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) (192–194) is an exposure-based therapy that combines eye movements, trauma, memory recall, and verbalization. EMDR appears to be as effective as other exposure-based therapies, but the eye movement component of the treatment may be unnecessary (192, 193). Most EMDR studies have been small, with variable methodological quality and outcomes.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Psychodynamic therapy for PTSD is underresearched, but it is probably efficacious (195). Only one controlled trial has evaluated psychodynamic therapy in comparison with other psychosocial treatments (trauma desensitization or hypnotherapy) and a control group (196). In this trial, all three psychosocial treatments were significantly more effective than the control treatment in improving PTSD symptoms of intrusion and avoidance. Although psychodynamic therapy had the least total effect on these symptoms when compared with the other two active treatments, follow-up data showed that the psychodynamic treatment group had the greatest improvement after treatment.

Hypnosis.

The literature on hypnosis in PTSD consists largely of case studies. One small controlled trial found that hypnosis and desensitization significantly decreased intrusive symptoms in PTSD (196). Hypnosis may best serve in an adjuvant role with other psychosocial interventions.

Psychological debriefing.

Psychological debriefing was developed to prevent PTSD after traumatic stress exposure. However, at present there is no evidence that it is effective for this purpose (197, 198). Psychological debriefing is a staged, semistructured intervention that addresses both facts and feelings related to the trauma. It also employs psychoeducation to help normalize the patient’s reaction to the trauma and to help foster coping skills and disengagement. Some trauma survivors have reported that group debriefing modalities were helpful (199), but other reports note that psychological debriefing may be harmful (198).

Future directions

In the past decade, important advances have been made in our understanding of the epidemiology of trauma reactions, the immediate and long-term neurobiological and psychological responses to traumatic stress, and the impact of pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments in PTSD. These developments, however, represent the early stages in our understanding of the human response to traumatic stress. Among the many directions for future investigation are the topics discussed below.

Acute stress reactions and early posttrauma treatment.

Treatment for acute stress reactions aims to reduce current distress and to prevent stress disorders. Findings from several small controlled trials support the efficacy of cognitive behavioral approaches used in this way (200, 201), but data from controlled studies for pharmacologic interventions are lacking. Two recent small controlled pilot studies suggest that early posttrauma treatment with propranolol (180) or imipramine (202) may be beneficial in reducing posttraumatic symptoms, whereas acute treatment with benzodiazepines may increase the likelihood of subsequent development of PTSD (162, 163). It is possible that acute intervention may alter the putative disease process, and studies are needed to evaluate potential neurobiological changes associated with acute treatment and to establish the long-term effects of these interventions.

Diagnosis and treatment of partial PTSD.

Many traumatized persons develop subsyndromal PTSD, often meeting criteria for reexperiencing and hyperarousal but not the avoidance/numbing requirement (20, 203). Although these individuals are less impaired than those with full PTSD, their condition is associated with significant psychosocial impairment (5, 20, 204). This raises the question of the diagnostic accuracy of the current threshold for PTSD and hence whether we are failing to identify individuals with clinically significant symptoms who might benefit from treatment. Further investigation is needed to understand the place of partial PTSD in the spectrum of pathological stress reactions.

Resilience and PTSD.

Resilience is one of the determining factors in an individual’s ability to deal with stress, yet it remains a neglected aspect of clinical therapeutics. Resilience has particular relevance to PTSD, because this disorder compromises stress coping capabilities, frequently leaving those with the disorder feeling more vulnerable to the effects of daily stress (unpublished 2002 study by K. M. Connor and J. R. T. Davidson) and, in some cases, with a greater susceptibility to developing PTSD from subsequent traumas than those who have not been previously exposed (205, 206). Little is known about the multifactorial determinants of resilience and the relationship of resilience to PTSD: is impaired resilience a risk factor for PTSD or a consequence of the disorder? Recent evidence, however, indicates that resilience is modifiable with treatment, and this suggests that perhaps resilience may be viewed as another target of intervention (142).

Ethnocultural considerations.

Cultural distinctions occur in the perception and interpretation of traumatic experiences, the expression of the response to the event, the cultural context of the response by the victim and his or her community, and the path to recovery. These differences create tremendous challenges in cross-cultural research on PTSD. Other impediments to research in this field include ethnocentrism, conceptual equivalence (e.g., linguistic, metric, and functional), the chaos that accompanies mass trauma, and the economics of multinational research efforts. Studies are needed to help further our understanding of the boundaries of PTSD and trauma by exploring differences across cultures.

Disclosure of Unapproved or Investigational Use of a Product

APA policy requires disclosure of unapproved or investigational uses of products discussed in CME programs. Off-label use of medications by individual physicians is permitted and common. Decisions about off-label use can be guided by the scientific literature, and clinical experience. All drug treatments (except sertraline and paroxetine) and all psychosocial treatments are not FDA approved for treating PTSD.

| A. | Traumatic stressor |

| • An event, or events, in which an individual experiences, witnesses, or is confronted with life endangerment, death, or serious injury or threat to self or others; and | |

| • The individual responds to the experience with feelings of intense fear, horror, or helplessness | |

| B. | Reexperiencing symptoms (one or more) |

| • Intrusive recollections; distressing dreams; flashbacks; dissociative phenomenon; psychological and physical distress with reminders of the event | |

| C. | Avoidance and numbing symptoms (three or more) |

| • Avoidance of thoughts, feelings, or conversations associated with the event; avoidance of places, situations, or people that are reminiscent of the event; inability to recall important aspects of the event; diminished interest; estrangement from others; restricted range of affect; sense of a foreshortened future | |

| D. | Hyperarousal symptoms (two or more) |

| • Sleep disruption; impaired concentration; irritability or anger outbursts; hypervigilance; exaggerated startle reaction | |

| E. | Minimum symptom duration of 1 month |

| F. | Symptoms cause distress or functional impairment |

|

Table 2. Clinical Domains of Assessment in PTSD Evaluation

|

Table 3. Pharmacotherapy for PTSD

|

Table 4. Psychosocial Treatments for PTSD

1 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1980Google Scholar

2 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Google Scholar

3 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

4 World Health Organization: The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

5 Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR: Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1114–1119Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Norris FH: Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:409–418Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:626–632Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy L: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population: findings of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1630–1634Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Davidson JR, Hughes D, Blazer DG, George LK: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med 1991; 21:713–721Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000; 22:261–269Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Samson AY, Bensen S, Beck A, Price D, Nimmer C: Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. J Fam Pract 1999; 48:222–227Google Scholar

14 Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V: Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA 2002; 288:1235–1244Crossref, Google Scholar

15 North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Mallonee S, McMillen JC, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM: Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA 1999; 282:755–762Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Weine SM, Becker DF, McGlashan TH, Laub D, Lazrove S, Vojvoda D, Hyman L: Psychiatric consequences of “ethnic cleansing”: clinical assessments and trauma testimonies of newly resettled Bosnian refugees. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:536–542Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Thabet AA, Vostanis P: Post-traumatic stress reactions in children of war. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999; 40:385–391Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:979–986Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Nishizawa S, Benkelfat C, Young SN, Leyton M, Mzengeza S, de Montigny C, Blier P, Diksic M: Differences between males and females in rates of serotonin synthesis in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94:5308–5313Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Zlotnick C, Franklin CL, Zimmerman M: Does “subthreshold” posttraumatic stress disorder have any clinical relevance? Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:413–419Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Weiss DS, Marmar CR, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordon BK, Hough RL, Kulka RA: The prevalence of lifetime and partial post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam theater veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1992; 5:365–376Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Carlier IV, Gersons BP: Partial posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): the issue of psychological scars and the occurrence of PTSD symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995; 183:107–109Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Guthrie RM, Moulds ML: A prospective study of psychophysiological arousal, acute stress disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:341–344Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Marshall RD, Spitzer R, Liebowitz MR: Review and critique of the new DSM-IV diagnosis of acute stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1677–1685Google Scholar

25 Shalev AY: Acute stress reactions in adults. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:532–543Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Brewin CR, Andrews B, Rose S, Kirk M: Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of violent crime. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:360–366Google Scholar

27 Harvey AG, Bryant RA: Predictors of acute stress following mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1998; 12:147–154Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Rothbaum BO, Foa EB: Subtypes of posttraumatic stress disorder and duration of symptoms, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson JRT, Foa EB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 23–35Google Scholar

29 McFarlane AC: The longitudinal course of posttraumatic morbidity: the range of outcomes and their predictors. J Nerv Ment Dis 1988; 176:30–39Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Solomon Z: Psychological sequelae of war: a 3-year prospective study of Israeli combat stress reaction casualties. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:342–346Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Perry S, Difede J, Musngi G, Frances AJ, Jacobsberg L: Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder after burn injury. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:931–935Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Breslau N, Davis GC: Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:671–675Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Zlotnick C, Warshaw M, Shea MT, Allsworth J, Pearlstein T, Keller MB: Chronicity in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and predictors of course of comorbid PTSD in patients with anxiety disorders. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:89–100Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Kessler RC: Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 5):4–12; discussion 13–14Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Pelcovitz D, van der Kolk B, Roth S, Mandel F, Kaplan S, Resick P: Development of a criteria set and a structured interview for disorders of extreme stress (SIDES). J Trauma Stress 1997; 10:3–16Google Scholar

36 Roth S, Newman E, Pelcovitz D, van der Kolk B, Mandel FS: Complex PTSD in victims exposed to sexual and physical abuse: results from the DSM-IV Field Trial for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Trauma Stress 1997; 10:539–555Google Scholar

37 McLean LM, Gallop R: Implications of childhood sexual abuse for adult borderline personality disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:369–371Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Goodman M, Yehuda R: The relationship between psychological trauma and borderline personality disorder. Psych Annals 2002; 32:337–345Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Hamner MB, Frueh BC, Ulmer HG, Huber MG, Twomey TJ, Tyson C, Arana GW: Psychotic features in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia: comparative severity. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:217–221Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Hamner MB, Frueh BC, Ulmer HG, Arana GW: Psychotic features and illness severity in combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:846–852Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE: Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:617–626Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Koss MP, Woodruff WJ, Koss PG: Relation of criminal victimization to health perceptions among women medical patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990; 58:147–152Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Golding JM: Sexual assault history and physical health in randomly selected Los Angeles women. Health Psychol 1994; 13:130–138Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Irwin KL, Edlin BR, Wong L, Faruque S, McCoy HV, Word C, Schilling R, McCoy CB, Evans PE, Holmberg SD: Urban rape survivors: characteristics and prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted infections. Multicenter Crack Cocaine and HIV Infection Study Team. Obstet Gynecol 1995; 85:330–336Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Laws A, Golding JM: Sexual assault history and eating disorder symptoms among White, Hispanic, and African-American women and men. Am J Public Health 1996; 86:579–582Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Dansky BS, Brewerton TD, Kilpatrick DG, O’Neil PM: The National Women’s Study: relationship of victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder to bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 1997; 21:213–228Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Harlow LL, Quina K, Morokoff PJ, Rose JS, Grimley DM: HIV risk in women: a multifaceted model. Journal of Applied Behavior Research 1993; 1:3–38Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Warshaw MG, Fierman E, Pratt L, Hunt M, Yonkers KA, Massion AO, Keller MB: Quality of life and dissociation in anxiety disorder patients with histories of trauma or PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1512–1516Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Breslau N: Outcomes of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 17):55–59Google Scholar

50 Malik ML, Connor KM, Sutherland SM, Smith RD, Davison RM, Davidson JR: Quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study assessing changes in SF-36 scores before and after treatment in a placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:387–393Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, Ballenger JC, Fyer AJ: The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:427–435Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Murray CJ, Lopez AD: Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause, 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997; 349(9064):1498–1504Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Charney DS, Deutch AY, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Davis M: Psychobiologic mechanisms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:295–305Google Scholar

54 Armony JL, LeDoux JE: How the brain processes emotional information. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 821:259–270Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Gold PB, Engdahl BE, Eberly RE, Blake RJ, Page WF, Frueh BC: Trauma exposure, resilience, social support, and PTSD construct validity among former prisoners of war. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2000; 35:36–42Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Gold J, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D, Stuber J, Vlahov D: Posttraumatic stress disorder in Manhattan, New York City, after the September 11th terrorist attacks. J Urban Health 2002; 79:340–353Crossref, Google Scholar

57 van der Kolk BA, MacFarlane AC, Weisaeth L: Traumatic Stress. New York, Guilford Press, 1996Google Scholar

58 Mellman TA, David D, Bustamante V, Fins AI, Esposito K: Predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder following severe injury. Depress Anxiety 2001; 14:226–231Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Stein MB, Sieber WJ: Gender differences in long-term posttraumatic stress disorder outcomes after major trauma: women are at higher risk of adverse outcomes than men. J Trauma 2002; 53:882–888Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Zatzick DF, Kang SM, Muller HG, Russo JE, Rivara FP, Katon W, Jurkovich GJ, Roy-Byrne P: Predicting posttraumatic distress in hospitalized trauma survivors with acute injuries. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:941–946Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Bremner JD, Southwick S, Brett E, Fontana A, Rosenheck R, Charney DS: Dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:328–332Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Freedman SA, Brandes D, Peri T, Shalev A: Predictors of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. A prospective study. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:353–359Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Regehr C, Hill J, Glancy GD: Individual predictors of traumatic reactions in firefighters. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:333–339Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Yehuda R, Halligan SL, Bierer LM: Relationship of parental trauma exposure and PTSD to PTSD, depressive and anxiety disorders in offspring. J Psychiatr Res 2001; 35:261–270Crossref, Google Scholar

65 McCranie EW, Hyer LA, Boudewyns PA, Woods MG: Negative parenting behavior, combat exposure, and PTSD symptom severity: test of a person-event interaction model. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:431–438Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Famularo R, Fenton T, Kinscherff R, Ayoub C, Barnum R: Maternal and child posttraumatic stress disorder in cases of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl 1994; 18:27–36Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Caselli LT, Motta RW: The effect of PTSD and combat level on Vietnam veterans’ perceptions of child behavior and marital adjustment. J Clin Psychol 1995; 51:4–12Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Cournos F: The trauma of profound childhood loss: a personal and professional perspective. Psychiatr Q 2002; 73:145–156Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Fearon RM, Mansell W: Cognitive perspectives on unresolved loss: insights from the study of PTSD. Bull Menninger Clin 2001; 65:380–396Crossref, Google Scholar

70 King LA, King DW, Fairbank JA, Keane TM, Adams GA: Resilience-recovery factors in post-traumatic stress disorder among female and male Vietnam veterans: hardiness, postwar social support, and additional stressful life events. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998; 74:420–434Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE: Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2002; 11:465–476Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Campbell R, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Wasco SM, Barnes HE: Social reactions to rape victims: healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence Vict 2001; 16:287–302Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Jacobsen PB, Sadler IJ, Booth-Jones M, Soety E, Weitzner MA, Fields KK: Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology following bone marrow transplantation for cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70:235–240Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Pedersen SS, Middel B, Larsen ML: The role of personality variables and social support in distress and perceived health in patients following myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53:1171–1175Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Yehuda R: Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:108–114Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Yehuda R: Current status of cortisol findings in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002; 25:341–368, viiCrossref, Google Scholar

77 Baker DG, West SA, Nicholson WE, Ekhator NN, Kasckow JW, Hill KK, Bruce AB, Orth DN, Geracioti TD Jr: Serial CSF corticotropin-releasing hormone levels and adrenocortical activity in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:585–588Google Scholar

78 Resnick HS, Yehuda R, Pitman RK, Foy DW: Effect of previous trauma on acute plasma cortisol level following rape. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1675–1677Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Rasmusson AM, Lipschitz DS, Wang S, Hu S, Vojvoda D, Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Charney DS: Increased pituitary and adrenal reactivity in premenopausal women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:965–977Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Rivier C: Gender, sex steroids, corticotropin-releasing factor, nitric oxide, and the HPA response to stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1999; 64:739–751Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Smith MA, Davidson J, Ritchie JC, Kudler H, Lipper S, Chappell P, Nemeroff CB: The corticotropin-releasing hormone test in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 26:349–355Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Southwick SM, Morgan CA III, Charney DS, High JR: Yohimbine use in a natural setting: effects on posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:442–444Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Lemieux AM, Coe CL: Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for chronic neuroendocrine activation in women. Psychosom Med 1995; 57:105–115Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Southwick SM, Davis M, Horner B, Cahill L, Morgan CA III, Gold PE, Bremner JD, Charney DC: Relationship of enhanced norepinephrine activity during memory consolidation to enhanced long-term memory in humans. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1420–1422Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Pitman RK: Post-traumatic stress disorder, hormones, and memory. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 26:221–223Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Fichtner CG, Arora RC, O’Connor FL, Crayton JW: Platelet paroxetine binding and fluoxetine pharmacotherapy in posttraumatic stress disorder: preliminary observations on a possible predictor of clinical treatment response. Life Sci 1994; 54:PL39–PL44Google Scholar

87 Maguire K, Norman T, Burrows G, Hopwood M, Morris P: Platelet paroxetine binding in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 1998; 77:1–7Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Arora RC, Fichtner CG, O’Connor F, Crayton JW: Paroxetine binding in the blood platelets of post-traumatic stress disorder patients. Life Sci 1993; 53:919–928Crossref, Google Scholar

89 Davis LL, Clark DM, Kramer GL, Moeller FG, Petty F: D-fenfluramine challenge in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:928–930Crossref, Google Scholar

90 Southwick SM, Paige S, Morgan CA III, Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Charney DS: Neurotransmitter alterations in PTSD: catecholamines and serotonin. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 1999; 4:242–248Google Scholar

91 Davidson JR, Rothbaum BO, van der Kolk BA, Sikes CR, Farfel GM: Multicenter, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:485–492Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Marshall RD, Beebe KL, Oldham M, Zaninelli R: Efficacy and safety of paroxetine treatment for chronic PTSD: a fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1982–1988Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Deutch AY, Roth RH: The determinants of stress-induced activation of the prefrontal cortical dopamine system. Prog Brain Res 1990; 85:367–402; discussion 402–403Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Abercrombie ED, Keefe KA, DiFrischia DS, Zigmond MJ: Differential effect of stress on in vivo dopamine release in striatum, nucleus accumbens, and medial frontal cortex. J Neurochem 1989; 52:1655–1658Crossref, Google Scholar

95 Vanitallie TB: Stress: a risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism 2002; 51(6 suppl 1):40–45Crossref, Google Scholar

96 Segman RH, Cooper-Kazaz R, Macciardi F, Goltser T, Halfon Y, Dobroborski T, Shalev AY: Association between the dopamine transporter gene and posttraumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7:903–907Crossref, Google Scholar

97 Young RM, Lawford BR, Noble EP, Kann B, Wilkie A, Ritchie T, Arnold L, Shadforth S: Harmful drinking in military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: association with the D2 dopamine receptor A1 allele. Alcohol Alcohol 2002; 37:451–456Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Randall PK, Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Nagy LM, Heninger GR, Nicolaou AL, Charney DS: Effects of the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil in PTSD. Biol Psychiatry 1995; 38:319–324Crossref, Google Scholar

99 Gavish M, Laor N, Bidder M, Fisher D, Fonia O, Muller U, Reiss A, Wolmer L, Karp L, Weizman R: Altered platelet peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 14:181–186Crossref, Google Scholar

100 Bremner JD, Innis RB, Southwick SM, Staib L, Zoghbi S, Charney DS: Decreased benzodiazepine receptor binding in prefrontal cortex in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1120–1126Crossref, Google Scholar

101 Spivak B, Maayan R, Kotler M, Mester R, Gil-Ad I, Shtaif B, Weizman A: Elevated circulatory level of GABA(A)–antagonistic neurosteroids in patients with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med 2000; 30:1227–1231Crossref, Google Scholar

102 Friedman MJ, Southwick SM: Towards pharmacotherapy for PTSD, in Neurobiological and Clinical Consequences of Stress: From Normal Adaptation to PTSD. Edited by Friedman MJ. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1995, pp 465–481Google Scholar

103 Wong CM: Post-traumatic stress disorder: advances in psychoneuroimmunology. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002; 25:369–383, viiCrossref, Google Scholar

104 Bremner JD, Randall P, Scott TM, Bronen RA, Seibyl JP, Southwick SM, Delaney RC, McCarthy G, Charney DS, Innis RB: MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:973–981Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Gurvits TV, Shenton ME, Hokama H, Ohta H, Lasko NB, Gilbertson MW, Orr SP, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, McCarley RW, Pitman RK: Magnetic resonance imaging study of hippocampal volume in chronic, combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:1091–1099Crossref, Google Scholar

106 Villarreal G, Hamilton DA, Petropoulos H, Driscoll I, Rowland LM, Griego JA, Kodituwakku PW, Hart BL, Escalona R, Brooks WM: Reduced hippocampal volume and total white matter volume in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 52:119–125Crossref, Google Scholar

107 Bonne O, Brandes D, Gilboa A, Gomori JM, Shenton ME, Pitman RK, Shalev AY: Longitudinal MRI study of hippocampal volume in trauma survivors with PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1248–1251Crossref, Google Scholar

108 De Bellis MD, Hall J, Boring AM, Frustaci K, Moritz G: A pilot longitudinal study of hippocampal volumes in pediatric maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:305–309Crossref, Google Scholar

109 De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Clark DB, Casey BJ, Giedd JN, Boring AM, Frustaci K, Ryan ND: AE Bennett Research Award: Developmental traumatology. part II: brain development. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:1271–1284Crossref, Google Scholar

110 Schuff N, Neylan TC, Lenoci MA, Du AT, Weiss DS, Marmar CR, Weiner MW: Decreased hippocampal N-acetylaspartate in the absence of atrophy in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:952–959Crossref, Google Scholar

111 Osuch EA, Benson B, Geraci M, Podell D, Herscovitch P, McCann UD, Post RM: Regional cerebral blood flow correlated with flashback intensity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:246–253Crossref, Google Scholar

112 Rauch SL, Whalen PJ, Shin LM, McInerney SC, Macklin ML, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Exaggerated amygdala response to masked facial stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder: a functional MRI study. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:769–776Crossref, Google Scholar

113 Liberzon I, Taylor SF, Amdur R, Jung TD, Chamberlain KR, Minoshima S, Koeppe RA, Fig LM: Brain activation in PTSD in response to trauma-related stimuli. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:817–826Crossref, Google Scholar

114 Lanius RA, Williamson PC, Densmore M, Boksman K, Gupta MA, Neufeld RW, Gati JS, Menon RS: Neural correlates of traumatic memories in posttraumatic stress disorder: a functional MRI investigation. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1920–1922Crossref, Google Scholar

115 Shin LM, Whalen PJ, Pitman RK, Bush G, Macklin ML, Lasko NB, Orr SP, McInerney SC, Rauch SL: An fMRI study of anterior cingulate function in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:932–942Crossref, Google Scholar

116 Hamner MB, Lorberbaum JP, George MS: Potential role of the anterior cingulate cortex in PTSD: review and hypothesis. Depress Anxiety 1999; 9:1–14Crossref, Google Scholar

117 McLeod DS, Koenen KC, Meyer JM, Lyons MJ, Eisen S, True W, Goldberg J: Genetic and environmental influences on the relationship among combat exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and alcohol use. J Trauma Stress 2001; 14:259–275Crossref, Google Scholar

118 King JA, Abend S, Edwards E: Genetic predisposition and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder in an animal model. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:231–237Crossref, Google Scholar

119 Connor KM, Davidson JR: Familial risk factors in posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 821:35–51Crossref, Google Scholar

120 Radant A, Tsuang D, Peskind ER, McFall M, Raskind W: Biological markers and diagnostic accuracy in the genetics of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 2001; 102:203–215Crossref, Google Scholar

121 Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR: Gender differences in susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38:619–628Crossref, Google Scholar

122 Goodman LA, Corcoran C, Turner K, Yuan N, Green BL: Assessing traumatic event exposure: general issues and preliminary findings for the Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire. J Trauma Stress 1998; 11:521–542Crossref, Google Scholar

123 Escalona R, Tupler LA, Saur CD, Krishnan KR, Davidson JR: Screening for trauma history on an inpatient affective-disorders unit: a pilot study. J Trauma Stress 1997; 10:299–305Google Scholar

124 Rodriguez N, Ryan SW, Vande Kemp H, Foy DW: Posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a comparison study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:53–59Crossref, Google Scholar

125 Meltzer-Brody S, Churchill E, Davidson JR: Derivation of the SPAN, a brief diagnostic screening test for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 1999; 88:63–70Crossref, Google Scholar

126 Breslau N, Peterson EL, Kessler RC, Schultz LR: Short screening scale for DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:908–911Crossref, Google Scholar

127 Brewin CR, Rose S, Andrews B, Green J, Tata P, McEvedy C, Turner S, Foa EB: Brief screening instrument for post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 181:158–162Crossref, Google Scholar

128 Ventureyra VA, Yao SN, Cottraux J, Note I, De Mey-Guillard C: The validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Scale in posttraumatic stress disorder and nonclinical subjects. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71:47–53Crossref, Google Scholar

129 Walker EA, Newman E, Dobie DJ, Ciechanowski P, Katon W: Validation of the PTSD checklist in an HMO sample of women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002; 24:375–380Crossref, Google Scholar