Ethics Commentary: Ethics in Psychotherapy

A 58-year-old businessman has been in therapy for 3 months for depressive symptoms and is progressing well. He requests that the next therapy session take place at a coffee shop because it is closer to his office and “more comfortable.” The patient offers an increased hourly rate in exchange for any inconvenience this might cause the therapist.

Psychiatrists routinely encounter situations in practice that require the utmost ethical consideration. Even within the field of psychiatry, the practice of psychotherapy creates unique ethical situations. The amount of time spent with patients in therapy combined with the intimate sharing on the part of the patient creates an inherent level of vulnerability. Further, people generally seek out therapy when they are in a difficult emotional state, which only serves to increase patient vulnerability (1). The imbalance of emotional exposure between a therapist and patient is part of what creates ethical dilemmas; it also is why the responsibility to uphold ethical standards and incorporate ethical principles into daily practice lies with the psychotherapist. Because of this responsibility, identifying ethical issues as they arise and understanding how one's personal values and beliefs may affect the therapeutic relationship are paramount to maintaining professionalism and ethics in psychotherapy (2).

CREATING AN ETHICAL FRAMEWORK

Ethics in psychotherapy can be thought of as a frame that defines the therapeutic relationship (3). The frame represents not just boundaries but also the form and expectations of the therapy, which should be decided by the therapist. This includes the location of the therapy, fees, documentation, limits to confidentiality, and conditions under which therapy could be terminated (3, 4). This frame is ideally set up at the initiation of therapy, so that the patient is cognizant of the therapeutic arrangement, and can then flow into obtaining informed consent for the therapeutic process, which is now thought to be a positive step in the initiation of psychotherapy by building patient autonomy, upholding patient rights, and protecting patient well-being (5).

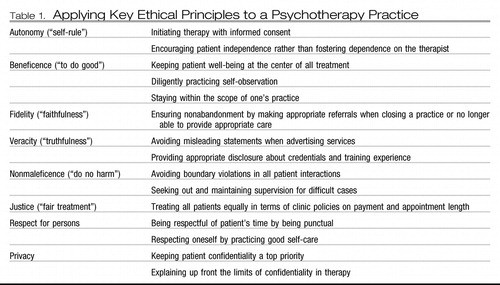

How does a psychotherapist construct an ethical frame in his or her practice? Here is where the overriding principles in medical ethics—beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, autonomy, fidelity, veracity, privacy, and respect for persons—can be used as a guide (6, 7). Table 1 breaks down the ethical principles and gives examples of how they can be incorporated into daily psychotherapy practice.

|

Table 1. Applying Key Ethical Principles to a Psychotherapy Practice

Being mindful of the ethical framework is a necessary starting point, but long-term psychotherapy often presents challenges to this framework that may not exist in other physician-patient relationships. The therapeutic “tool” in psychotherapy is the therapist; the platform for healing is the therapeutic relationship. In contrast with other medical specialties, in which the main therapeutic tool is a scalpel or a prescription for medication (1), the tool, a human, is inherently imperfect and open to vulnerabilities and temptations. Thus, professionalism and the ethical principle of beneficence, or the duty to “do good” for the patient, need to be placed at the heart of every patient interaction.

To adhere to the principle of beneficence, safeguards should be built into every psychotherapeutic practice in the form of a commitment to honest self-observation and supervision (2). Self-observation and supervision serve to support professional behavior by forcing the therapist to examine personal motives, needs, or wishes that may be challenging the frame of the ethical therapeutic relationship. Three common areas in which ethical challenges arise are boundaries, confidentiality, and termination of therapy.

BOUNDARIES

Boundaries in psychotherapy are especially important because of the deep emotional investment and attachment that develop in therapy. Maintaining appropriate boundaries begins with recognizing when boundary issues arise (1). Although some boundaries are firm, such as avoiding sexual contact with any current or former patient (8), it is now recognized that some boundaries are more fluid. This is the distinction between a boundary crossing, which can be benign or even beneficial, and a boundary violation, which is harmful (3). The distinction lies not only in the boundary itself but also in the patient and the situation. For example, having a therapy session outside of the office would usually be considered a boundary violation. However, in the case of a patient with agoraphobia with whom cognitive behavior therapy is being used in a crowded shopping center, this boundary crossing is actually therapeutic.

Contrast this with the request of the businessman in the opening example. There is no therapeutic advantage to having a session closer to a patient's place of employment. One cannot be sure about the conscious or unconscious motives for the patient's request. Does he wish to shift the asymmetry of power by designating the setting himself? Is he trying to “buy” a concession from the therapist? We cannot tell with the limited information we have, but there is reason to be concerned that this could be the beginning of a descent to boundary violations that would be detrimental to the therapy itself and to the patient.

The psychotherapist can use several strategies to safeguard against boundary violations. These include being familiar with ethical standards and opinions on boundary issues, staying within the scope of one's practice, paying attention to emotional “red flags” or feelings of uneasiness, and having access to an honest, trustworthy supervisor or consultant (2, 9). The overriding ethical principle in all of these safeguards involving boundaries is beneficence. In other words, one attempts to ensure that in all therapist actions, the commitment to “do good” for the patient is above the therapist's personal motivations and wishes. Unfortunately, one cannot always know how unconscious influences enter into one's decisions.

CONFIDENTIALITY: AN EVOLVING ETHICAL CHALLENGE

A psychiatrist has agreed to see a physician for psychotherapy who works in the same medical facility. The physician has sought out psychotherapy for a failing marriage and his worsening drinking problem. The hospital uses an electronic medical record (EMR) for all records, including psychotherapy notes. The physician requests that the details of his drinking not be documented in the EMR, because it could adversely affect his career.

Confidentiality is central to building and maintaining the therapeutic relationship. However, between third-party payers and the advancement of EMRs, the ability to maintain confidentiality is continually threatened (1). The major ethical principles involving confidentiality are privacy, nonmaleficence, and respect for persons. Privacy in medicine refers to the positive obligation to protect and not share personal information or observations about a patient without his or her express permission. Confidentiality is a privilege because there are, at times, ethical imperatives that take precedence over confidentiality, for example, in the case of suspected child or elder abuse. Similarly, there may be a positive duty, under Tarasoff, to protect a named potential victim of a homicidal patient (7). These obligations to break confidentiality are mandated by law typically. In other words, it is ethical to not protect a person's information if it would result in direct risk of harm to others. It is important to note that in any case of sharing a patient's personal information, no more than the minimum information needed to uphold the law should be given (7).

As stated earlier, some cases of breaking confidentially are clear-cut and legally mandated, such as the duty to report child and elder abuse. However, what about the example of a possibly impaired colleague? In this case, seeking supervision from a more experienced clinician, possibly one with advanced knowledge on substance abuse, would aid in further assessment of actual impairment and risk to third parties (1). Substance abuse is not synonymous with impairment.

A similar type of ethical quandary surrounding confidentiality comes up frequently in child psychiatry when a parent wants information about an adolescent's confidential therapy session. Actual laws vary by state, but in general the best approach to confidentiality with adolescent children is an upfront discussion with parents and the child regarding confidentiality expectations and limits before engaging in therapy (10). Confidentiality and ethics in general tend to be more difficult with children. However, the guiding ethical principles of nonmaleficence and beneficence, that is, acting in the best interest of the child, still apply (10).

Ethics opinions related to psychotherapy notes in the EMR are evolving, and a complete review is beyond the scope of this column. Nonetheless, in regard to this case and the request to “tailor” the chart, the therapist should always first strive for accuracy in the medical chart. However, the psychiatrist could consider advocating for secure psychotherapy records or for permission to keep a “shadow” chart in addition to the main chart for especially sensitive patients (1). Process notes kept for supervision are currently kept in files separate from the medical record in some training programs and are not discoverable. Of course, one should carefully self-monitor for nonethical motives behind any nonuniform decisions regarding documenting and record-keeping.

TERMINATION OF THERAPY

A therapist has had a difficult, emotionally challenging patient in treatment for the last 6 months. Over the last month the patient has made some small advances in therapy. The therapist begins to heavily compliment these minor achievements, secretly hoping that the patient will feel ready to terminate the relationship.

There are ethical issues in both the initiation and the termination of psychotherapy. Stating goals and expectations of care, limits to confidentiality, and informed consent were briefly discussed previously, along with creating an ethical framework, which is best initiated at the beginning of therapy. Termination of psychotherapy and its terms are also best discussed at the initiation of therapy (11, 12). This ensures an easier transition when termination does occur, no matter the reason.

Two key ethical principles that can guide the psychotherapist through termination of therapy are fidelity and nonmaleficence. Fidelity refers to the faithful dedication of the physician to the patient (6). In application, this refers to the ethical obligation of nonabandonment once a physician-patient relationship has been formed. Thus, in the case of a psychotherapy practice closure, the therapist should provide referrals to competent professionals who could take over the patient's care. Similarly, in cases that progress beyond the scope of a therapist's comfort level, supervision should be sought out and referral should be considered according to the best interests of the patient.

As this case illustrates, however, abandonment can occur subtly, in the form of burnout. When the psychotherapist no longer feels able to care for the patient due to compassion fatigue, supervision should be sought. Psychotherapists at this point may also benefit from careful self-reflection on their own wellness. If the situation continues to deteriorate, in the interest of nonmaleficence, the patient should be referred to another therapist (7).

Under better circumstances, termination of therapy occurs because a patient has met his or her stated goals of therapy. It is ethically important for the therapist to be able to recognize when a patient no longer needs therapy to prevent possible harm (nonmaleficence) with unnecessary treatment. Setting goals at the onset of therapy and regularly reviewing those goals are practical ways to achieve that aim (11, 12). Appropriately preparing a patient for termination of therapy by providing follow-up resources and community support as needed are ethically guided actions that work to benefit the patient and uphold psychiatrists' obligation of fidelity to patients.

CONCLUSION

The nature of the doctor-patient relationship in psychotherapy is complex and deeply emotional for most patients. Attention to the well-being and psychological safety of the patient must be a top priority. This necessitates utmost adherence to ethical principles. The core ethical practices of honest self-observation and supervision are the best tools to guide the therapist. Dedication to ethical standards must be a deliberate, conscientious, and continued commitment on the part of the therapist in daily practice.

1 Roberts LW, Dyer AR: Concise Guide to Ethics in Mental Health Care. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing 2004 Google Scholar

2 Roberts LW, Geppert CM, Bailey R: Ethics in psychiatric practice: essential ethics skills, informed consent, the therapeutic relationship, and confidentiality. J Psychiatr Pract 2002; 8:290–305 Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Gutheil TG, Gabbard GO: The concept of boundaries in clinical practice: theoretical and risk-management dimensions. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:188–196 Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Jain S, Roberts LW: Ethics in psychotherapy: a focus on professional boundaries and confidentiality. Psychiatr Clin N Am 2009; 32:299–314 Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Beahrs JO, Gutheil TG: Informed consent in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:4–10 Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Beauchamp TL, Childress JF: Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 5th ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001 Google Scholar

7 Roberts LW, Hoop JG, Dunn LB: Ethical aspects of psychiatry, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry, 5th ed. Edited by Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Gabbard GO. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2008, pp. 1601–1636 Google Scholar

8 American Psychiatric Association: The Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2009 Google Scholar

9 Pope KS, Keith-Spiegel P: A practical approach to boundaries in psychotherapy: making decisions, bypassing blunders, and mending fences. J Clin Psychol 2008; 54:638–652 Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Belitz J, Bailey RA: Clinical ethics for the treatment of children and adolescents: a guide for general psychiatrists. Psychiatr Clin N Am 2009; 32:243–257 Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Vasquez MJT, Bingham RP, Barnett JE: Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol 2008; 64:653–665 Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Gabbard GO: Long-Term Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: A Basic Text, 2nd ed. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2010 Google Scholar