Bipolar Disorders: A Brief Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis

In the early 1950s, Lewis and Piotrowski emphasized the difficulty diagnosing manic-depressive psychosis and concluded that “even a trace of schizophrenia is schizophrenia” (1). Their work helped relegate bipolar disorder to relative obscurity in the United States for many years. Today, as the nosologic pendulum swings toward the other extreme, the bipolar spectrum concept promises to expand far beyond its current boundaries. Angst and Gamma recently remarked, “Our data suggest that every depressive individual manifesting signs of hyperactivity, irritability, euphoria, or mood instability could well be bipolar” (2).

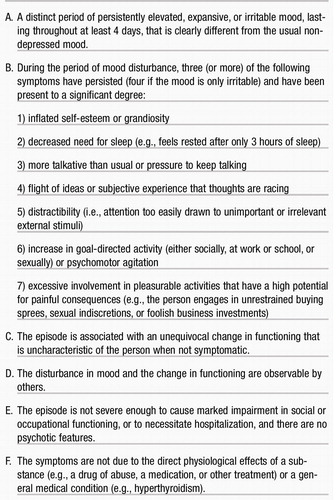

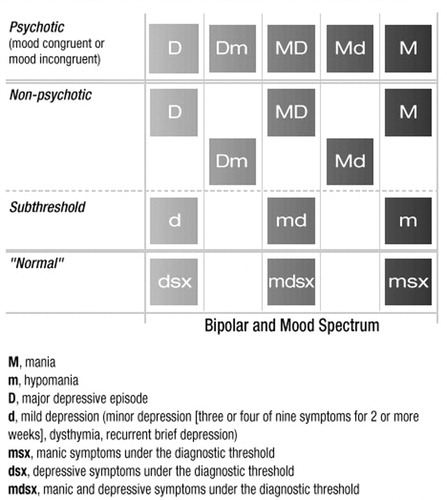

One of today’s diagnostic controversies has to do with the rather arbitrary DSM-IV-TR definition of hypomania (Table 1), in terms of symptoms as well as of duration criteria; for example, a patient with a history of at least one major depressive episode who has been hypomanic for 3 1/2 days would qualify for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder not otherwise specified but graduate the next day to bipolar II. The bipolar spectrum concept would redefine hypomania by adding hyperactivity to criterion A, require only three symptoms under criterion B, and eliminate any requirement for duration. Angst and Gamma speculate that with these changes, about half of those individuals currently diagnosed as having major depressive disorder would be reclassified as having bipolar II disorder (2). The bipolar spectrum would expand still further by incorporating subsyndromal entities such as recurrent brief hypomania and hypomania with dysthymia, minor depression, or recurrent brief depression (Figure 1). In the process of espousing the spectrum concept, Cassano et al. emphasize the widespread tendency to underdiagnose subthreshold forms of mania (3). Of course, as the line between hypomania and normality blurs further, the risk of overdiagnosing psychopathology increases considerably (tell a joke and you may be hypomanic, but tell several and you definitely are; road rage—another bipolar variant? and anyone buying a large high-definition plasma-screen television must certainly be hypomanic).

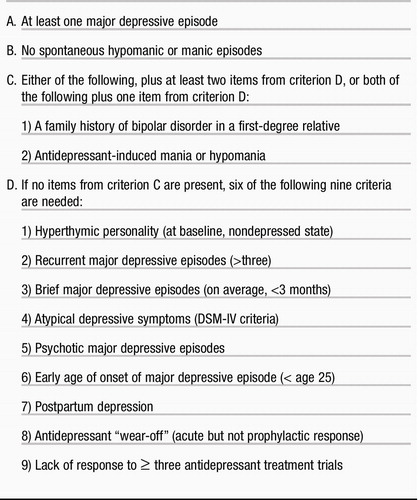

The spectrification of bipolar disorder extends well beyond redefining bipolar II disorder. Ghaemi et al. propose including patients with one or more major depressive episodes who meet certain criteria (Table 2), even if they have never had a spontaneous manic or hypomanic episode (4). Akiskal has been a strong proponent of a broader conceptualization of bipolar disorder, stating, for example, that “the depressive phase of bipolar II patients can, in a significant minority of patients, be replaced by subthreshold depressive, socially anxious, or obsessive inhibitions” (5). Today the bipolar spectrum threatens to overexpand to the extent that “even a trace of bipolar disorder is bipolar disorder.”

Proponents of the bipolar spectrum concept nevertheless agree with Baldessarini (6) that there is considerable need for further research to validate the components of their greatly expanded diagnostic chimera and to establish the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions for that wider range of conditions. After all, the assumption that what works for bipolar I disorder will also work for a spectrum condition such as “mild depression with hypomania” is just that—an assumption. In general, as conceptualizations of a disorder expand from a classic core definition (e.g., euphoric episodic mania with normal interepisode functioning) to a spectrum of related conditions and further beyond the spectrum to “fringe disorders,” the effectiveness of conventional treatments wanes.

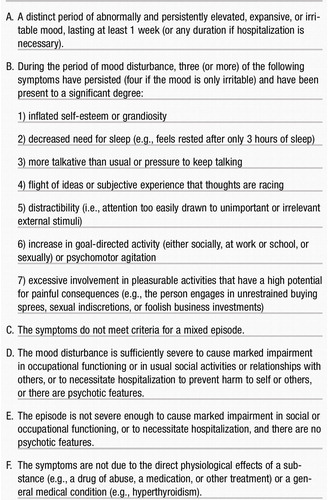

That said, where does this leave today’s clinician? As Ghaemi et al. point out, we do not do a very good job diagnostically even with well-defined bipolar I and bipolar II disorders, let alone with the more subtle nuances of the bipolar spectrum (4). They found that 40% of inpatients who had previously been diagnosed with major depressive disorder were reclassified with bipolar I disorder after a previously unrecognized manic episode came to light. Failure to recognize such an episode may be due in part to a clinician’s lack of familiarity with the diagnostic criteria for mania (Table 3) and in part to failure to extend the diagnostic process to significant others, to obtain past medical and psychiatric records, and to obtain a detailed family history. If a history of DSM-IV-TR mania often slips through the diagnostic cracks, imagine how often even fully defined DSM-IV-TR hypomania is missed. It certainly seems reasonable to recommend that a patient with a major depressive episode who is not responding well to conventional antidepressant treatment be thoroughly reevaluated, searching for that hidden history of bipolarity that would redirect treatment in a more productive direction.

Treatment

The APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision) (7) is quite well done and highly recommended reading for anyone treating patients with the disorder. At the same time, major advances are occurring in the field, and new and emerging data are continually reshaping practice. Consequently, the APA guideline should serve as the foundation for a never-ending educational process. The demands of clinical practice are such that evidence-based research (often the results of large, well-designed, double-blind, multicenter studies) carries us only so far, and beyond that, we must rely on innovation and creativity to go further. However, a balance must be struck between, on the one hand, overenthusiastic endorsement of the latest case series of a handful of patients that extols the merits of a certain drug and, on the other, thoughtfully exploring such possibilities only after more conventional, better-established treatments have failed. It would be difficult to justify exposing patients to a trial of zonisamide or levetiracetam (both currently under study for bipolar disorder) who have never been treated with lithium, whereas we should not fault Goldberg and Burdick for using levetiracetam (successfully) in a patient who had not responded adequately to lithium, divalproex, carbamazepine, neuroleptics, SSRIs, and psychostimulants (8).

Even the preliminary results of large double-blind multicenter trials presented orally or as posters at meetings should be viewed with cautious optimism rather than overzealous endorsement, reserving final judgment until the data appear in more elaborate detail in peer-reviewed journals.

Acute manic episodes

Perhaps the greatest impediment to the successful treatment of acute mania today is limitations imposed by managed care systems on the duration of hospitalization. Conventional and atypical antipsychotic drugs are widely used, effective interventions for both psychotic and severe nonpsychotic mania (the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved chlorpromazine and olanzapine for the purpose in 1973 and 2000, respectively); lithium (approved in 1970) and divalproex (1995) are first-line old standbys for mania; and carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine show merit. At the same time, neither gabapentin nor lamotrigine nor topiramate has successfully withstood the rigors of placebo-controlled acute mania trials.

More often than not, acute manic episodes are treated with combinations such as an atypical antipsychotic plus lithium or divalproex and perhaps an adjunctive benzodiazepine. After all, although Bowden et al. showed in their landmark study that both divalproex and lithium are twice as effective as placebo in reducing mania symptoms, at the end of 3 weeks the average mania rating scale scores for patients in both drug groups were still high enough to qualify them for entry into the study (9). Randomized placebo-controlled double-blind studies have found the combination of a mood stabilizer plus an antipsychotic to be more effective than a mood stabilizer alone or an antipsychotic alone for the treatment of acute mania (10, 11, 12).

Of great importance in treating acute mania is the time to onset of a clinically meaningful, not a just statistically significant, response. Adequate dosage is obviously important, as illustrated by the finding that starting with 10 mg daily of olanzapine took 3 weeks to separate from placebo, whereas starting with 15 mg daily accomplished the task in 1 week (13, 14). Oral ziprasidone bested placebo by day 2, but the absence of an active comparator does not allow the claim of “faster than” anything but placebo (15). Even loading doses of divalproex (20 or 30 mg/kg body weight per day) have not been shown clearly to hasten recovery or shorten hospitalization, although tolerability is generally good and therapeutic serum levels are reached quickly (16).

The first patient treated with lithium by John Cade in the late 1940s had been hospitalized for 5 years in a state of manic excitement. Today, manic episodes are considerably shorter, in large part because of the availability of a variety of effective pharmacological interventions. Of considerably greater concern is how to deal effectively with bipolar depression and with the long-term stabilization of bipolar disorder. Unlike the widely accepted mantra of major depressive disorder—“the drug that gets you better keeps you better,” the drug that gets the manic or depressed bipolar patient better may or may not be the drug that keeps him well.

Acute bipolar depression

The psychiatric world seems divided into those who feel that antidepressants are an anathema for bipolar patients and those who find them not particularly noxious and often quite useful. The Expert Consensus Guideline series, Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder, 2000 (17), listed lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine as preferred initial strategies for first-episode nonpsychotic bipolar depression. The inclusion of divalproex, whose antidepressive effectiveness has never been confirmed in controlled studies, suggests that even experts sometimes vote with their hearts and not their brains. The revised APA guideline, on the other hand, awarded first-line status only to lithium and lamotrigine (the latter largely on the basis of results of a large monotherapy study of bipolar I depression [N=195] in which most outcome measures favored lamotrigine over placebo [18]). A practical, but far from insurmountable, drawback to the use of this drug is the very slow titration required to minimize the risk of severe rash. Another concern with the use of lamotrigine as monotherapy is that although it does not appear to increase the risk of mania or hypomania, it does not appear to protect against these possibilities either.

In practice, either an inadequate response to lithium or lamotrigine alone or impatience while awaiting a response often results in the addition of an antidepressant. For years, the party line has been “choose your antidepressant wisely and discontinue it as soon as possible.” Despite the relative paucity of comparative studies, there seems to be a consensus that tricyclics are least preferred for bipolar depression, not because they are ineffective but rather because they appear to carry a greater risk of precipitating dysphoric, difficult-to-treat mania or hypomania. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, of course, are always held in high regard, but they are seldom used for obvious safety and tolerability reasons. That leaves all the “modern” antidepressants for consideration, with a slight edge favoring bupropion, although it is only now undergoing comparison with sertraline and venlafaxine in a double-blind study (19).

The recommendation that the duration of antidepressant use for bipolar depression be kept as short as possible has been challenged recently, on the basis of what appears to be substantial clinical experience and a retrospective record review describing patients in whom antidepressant discontinuation was equated with recurrence of depression and in whom antidepressant continuation was equated with mood stability (20, 21). On the other hand, Ghaemi concluded in a review of the literature that antidepressants have not been proven to prevent bipolar depression (22). With the emergence of lamotrigine as a bipolar antidepressant, combining it with lithium and thereby avoiding the use of conventional antidepressants has some appeal, although comparative studies have yet to be done.

In general, antidepressant monotherapy is frowned upon for bipolar depression because antidepressants provide no protection against (and may increase the risk of) manic or hypomanic episodes. However, there are circumstances in bipolar II depression when an antidepressant alone may be acceptable. Since bipolar II disorder tends to breed true, the risk of a full-blown manic episode is slim, and if the past history of hypomania has been one of easily tolerated euphoria, an antidepressant may be all that is needed. A comparative study pitting lamotrigine against a conventional antidepressant under such circumstances would be most welcome.

Much of the above also applies to dealing with breakthrough depressions. In addition, an underappreciated cause of such treatment failures is noncompliance, both partial and complete. A serum concentration of zero for a medication conveys a strong impression of noncompliance. More commonly, however, patients become careless with their regimen, missing doses here and there until the protective value of the medication is lost. In such situations, the periodic blood level monitoring used with patients taking drugs such as lithium, divalproex, and carbamazepine may allow the problem to be recognized and corrected in a way that is not possible with the newer, no-blood-tests-necessary medicines. By the way, if the breakthrough occurs in a patient on lithium, make sure you are not dealing with lithium-induced hypothyroidism.

No discussion of breakthrough depression would be complete without addressing the issue of which medication to add—a conventional antidepressant or a second mood stabilizer. Two studies thus far have sought the answer—one a 6-week double-blind comparison of lithium plus divalproex versus lithium or divalproex plus paroxetine (23) and the other an 8-week single-blind comparison of bupropion SR and topiramate as add-ons (24). Both studies found equal efficacy and no manic switches, so the issue remains unresolved, although there were differences in tolerability in both studies favoring the antidepressant.

Maintenance treatment

So what if lithium is the best-established maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder, the only drug approved by the FDA for this condition (lamotrigine is currently under consideration for the prevention of recurrent bipolar depression), and the only drug shown rather convincingly to reduce suicidality in bipolar patients? In fact, long-term lithium monotherapy is seldom fully effective (but then what is?), and this underappreciated, inexpensive, generic monovalent cation has little appeal to the marketers of proprietary products. Fortunately, the drug continues to rank among the chosen few in virtually all categories in guideline and consensus publications (7, 10, 25, 26). Not only that, but lithium is the best mixer with alternative agents in terms of tolerability and efficacy (although this statement is based more on clinical experience than on well-designed comparative studies). For example, although combinations such as divalproex and carbamazepine or divalproex and lamotrigine may prove valuable for treatment resistance, they carry greater risk and complexity than combining lithium with any of these three medications.

In addition to lithium, what other medications have documented long-term effectiveness? A wealth of clinical experience suggests the value of divalproex in this regard, although a 12-month, placebo-controlled maintenance study of bipolar I outpatients found that “the divalproex group did not differ significantly from the placebo group in time to any mood episode” (27). But then again, in this study, lithium was also no more effective than placebo, and some nonsignificant trends in secondary outcome measures did favor divalproex over lithium.

Two long-term placebo-controlled maintenance studies found both lithium and lamotrigine to be more effective than placebo. Although these data have been reported repeatedly at meetings (28, 29), peer-reviewed journal publications of the results are still pending. In brief, both studies were designed the same, with bipolar I patients entering in one after a recent manic or hypomanic episode and in the other after a recent depressive episode. After open-label stabilization with a variety of medications, patients were transferred to lamotrigine alone, and those who remained stable then underwent randomized, double-blind assignment to lamotrigine, lithium, or placebo. On the primary outcome measure of time to intervention for a mood episode, the two drugs were equally effective and considerably more effective than placebo. Perhaps of greater interest, and with implications favoring combination therapies, were the observations that lithium bested lamotrigine and placebo in time to intervention for a manic episode and lamotrigine bested both lithium and placebo in time to intervention for a depressive episode.

Lamotrigine’s apparent long-term impact on the depressive aspect of bipolar illness was further supported in a 6-month study of rapid cycling in which patients who were stabilized on open-label lamotrigine were randomized double-blind to either lamotrigine or placebo (30). Although lamotrigine was no more effective than placebo on the primary outcome measure—time to additional pharmacotherapy—a substantially greater proportion of patients were stable without relapse for 6 months on lamotrigine, and a decidedly greater difference between lamotrigine and placebo was observed in bipolar II patients, a group in which depression is the principal feature.

Most recently, preliminary results of a 12-month double-blind comparative study of olanzapine and lithium found both drugs effective in sustaining remission, but olanzapine more effective in preventing manic recurrence (31). The absence of a placebo control (which some would consider ethically justifiable) limits conclusions as to just how effective overall the two drugs were. The same can be said for a double-blind comparison of divalproex and olanzapine in which patients whose manic or mixed episodes remitted during short-term treatment were followed for an additional 44 weeks. In the preliminary report, nonsignificant trends favored olanzapine with regard to relapse rates and time to relapse (32).

Antipsychotics, both conventional and atypical, are commonly used in combination with conventional mood stabilizers for long-term treatment. Until recently, this widely accepted practice had little research support. Results—once again preliminary—of a relatively small 18-month study showed that patients randomly assigned to olanzapine plus lithium or valproate had significantly longer time to and rate of recurrence to mania but not to depression than those on placebo plus lithium or valproate (33).

Conclusions

The riddles of bipolar disorder are far from solved, but considerable progress has been made in the last decade across a broad front. The etiology remains elusive, yet advances in genetics, neuroimaging, and neurochemistry have been substantial. Without an established etiology, however, diagnosis remains descriptive and treatments based largely on the results of clinical trials and astute clinical observations. Nonetheless, today patients with bipolar disorder are much more likely to be diagnosed accurately (depending, in part, on where on the bipolar spectrum their illness falls) and treated effectively than patients were in the past.

One should not underestimate the value of education—for professionals, patients, and the laity in general—as the vehicle by which the best comprehensive evaluation and treatment are delivered. Appendix I of the APA revised guideline for bipolar disorder lists educational sources (note that the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association was renamed recently the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance). In addition, both the Lithium Information Center and the Bipolar Disorder Treatment Information Center at the Madison Institute of Medicine have enormous literature databases available to both professionals and the public (www.miminc.org).

Disclosure of Unapproved or Investigational use of a Product APA policy requires disclosure of unapproved or investigational uses of products discussed in CME programs. As of the date of publication of this CME program, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved lithium for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder; maprotiline for the treatment of bipolar disorder, depressed type; and divalproex for the treatment of bipolar disorder, manic episodes. All other uses are “off-label.” Off-label use of medications by individual physicians is permitted and common. Decisions about off-label use can be guided by the scientific literature and clinical experience.

|

Table 1. DSM-IV-TR Criteria for Hypomanic Episode

|

Table 2. A Proposed Definition of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder

|

Table 3. DSM-IV-TR Criteria for Manic Episode

Figure 1. Subgroups of the Bipolar Spectrum

Reproduced and reprinted, with permission, from Angst and Gamma (2).

1 Lewis NDC, Piotrowski ZA: Clinical diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis, in Depression. Edited by Hoch PH, Zubin J. Proceedings of the 42nd annual meeting of the American Psychopathological Association, New York City, June 1952. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1954, pp 25–38 Google Scholar

2 Angst J, Gamma A: Prevalence of bipolar disorders: traditional and novel approaches. Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorders 2002; 1:10–14 Google Scholar

3 Cassano GB, Dell’Osso L, Fran E, Miniati M, Fagiolini A, Shear K, Pini S, Maser J: The bipolar spectrum: a clinical reality in search of diagnostic criteria and an assessment methodology. J Affect Disord 1999; 54:319–328 Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Ghaemi SN, Ko JY, Goodwin FK: “Cade’s disease” and beyond: misdiagnosis, antidepressant use, and a proposed definition for bipolar spectrum disorder. Can J Psychiatry 2002; 47:125–134 Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Akiskal HS, Bourgeois ML, Angst J, Post R, Möller H-J, Hirschfeld R: Re-evaluating the prevalence of and diagnostic composition within the broad clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders. J Affect Disord 2000; 59:S5–S30 Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Baldessarini RJ: A plea for integrity of the bipolar disorder concept. Bipolar Disord 2000; 2:3–7 Crossref, Google Scholar

7 American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(Apr suppl) Google Scholar

8 Goldberg JF, Burdick KE: Levetiracetam for acute mania (letter). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:148 Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG (Depakote Mania Study Group): Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918–924 Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Sachs GS, Grossman F, Ghaemi SN, Okamoto A, Bowden CL: Combination of a mood stabilizer with risperidone or haloperidol for treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of efficacy and safety. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1146–1154 Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Retzow A, Henn FA, Giedke H, Walden J: Valproate as an adjunct to neuroleptic medication for the treatment of acute episodes of mania: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20:195–203 Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Tohen M, Chengappa KNR, Suppes T, Zarate CA Jr, Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Kupfer DJ, Baker RW, Risser RC, Keeter EL, Feldman PD, Tollefson GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine in combination with valproate or lithium in the treatment of mania in patients partially nonresponsive to valproate or lithium monotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:62–69 Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, McElroy SL, Banov MC, Janicak PG, Sanger T, Risser R, Zhang F, Toma V, Francis J, Tollefson GD, Breier A (Olanzapine HGGW Study Group): Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:841–849 Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702–709 Google Scholar

15 Keck PE Jr, Ice K: A 3-week, double-blind, randomized trial of ziprasidone in the acute treatment of mania. Presented at 40th annual meeting of the National Institute of Mental Health, New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEU), 2000, Boca Raton, FL Google Scholar

16 Hirschfeld RMA, Allen MH, McEvoy JP, Keck PE, Russell JM: Safety and tolerability of oral loading divalproex sodium in acutely manic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:815–818 Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Sachs GS, Printz DJ, Kahn DA, Carpenter D, Docherty JP: Medication treatment of bipolar disorder, 2000. The Expert Consensus Guidelines series. Postgraduate Medicine 2000; Special Issue:1–104 Google Scholar

18 Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Ascher JA, Monaghan E, Rudd GD (Lamictal 602 Study Group): A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:79–88 Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Post RM, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Rush AJ, Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, Kupka R, Nolen WA: Rate of switch in bipolar patients prospectively treated with second-generation antidepressants as augmentation to mood stabilizers. Bipolar Disord 2001; 3:259–265 Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, Goodman R, Gitlin M, Frye M, Mintz J: The impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation on 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:612–616 Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Möller HJ, Grunze H: Have some guidelines for the treatment of acute bipolar depression gone too far in the restriction of antidepressants? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 250:57–68 Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Ghaemi SN: Antidepressants and bipolar disorder: part II. do antidepressants prevent depression in bipolar disorder? International Drug Therapy Newsletter 2000; 35(5):33–37 Google Scholar

23 Young LT, Joffe RT, Robb JC, MacQueen GM, Marriott M, Patelis-Siotis I: Double-blind comparison of addition of a second mood stabilizer versus an antidepressant to an initial mood stabilizer for treatment of patients with bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:124–126 Crossref, Google Scholar

24 McIntyre RS, Mancini DA, McCann S, Srinivasan J, Sagman D, Kennedy SH: Topiramate versus bupropion SR when added to mood stabilizer therapy for the depressive phase of bipolar disorder: a preliminary single-blind study. Bipolar Disord 2002; 4:207–213 Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Bauer MS, Callahan AM, Jampala C, Petty F, Sajatovic M, Schaefer V, Wittlin B, Powell BJ: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:9–21 Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Berghöfer A, Bauer M: Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2002; 359:241–247 Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, Pope HG Jr, Chou JC, Keck PE Jr, Rhodes LJ, Swann AC, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ (Divalproex Maintenance Study Group): A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:481–489 Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Earl NL, Gyulai L, Sachs GS, Montgomery P: Lamotrigine demonstrates long-term mood stabilization in manic patients, in 2001 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2001 Google Scholar

29 Bowden CL, Ascher JA, Calabrese JR, Ginsburg A, Greene P, Montgomery P, Reimherr FW: Lamotrigine: evidence for mood stabilization in bipolar I depression, in 2001 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2001 Google Scholar

30 Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Swann AC, McElroy SL, Kusumakar V, Ascher JA, Earl NL, Greene PL, Monaghan ET (Lamictal 614 Study Group): A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:841–850 Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Tohen M, Marneros A, Bowden C, Calabrese J, Greil W, Koukopoulis A, Belmaker H, Jacobs T, Robert MAS, Baker RW, Williamson D, Evans AR, Cassano G: Olanzapine versus lithium in relapse prevention in bipolar disorder: a randomized double-blind controlled 12-month clinical trial. Bipolar Disord 2002; 4(suppl 1):135 Google Scholar

32 Baker RW, Tohen M, Altshuler L, Zarate CA, Suppes T, Ketter TA, Risser RC, Schuh L: Olanzapine versus divalproex sodium for treatment of acute mania and maintenance of remission: a 47-week study. Presented at the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 40th Annual Meeting, December 9–13, 2001, Waikoloa, HI Google Scholar

33 Tohen M, Chengappa KNR, Suppes T, Baker RW, Risser RC, Evans AR, Calabrese JR: Olanzapine combined with mood stabilizers in prevention of recurrence in bipolar disorder: an 18-month study. Presented at the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 40th Annual Meeting, December 9–13, 2001, Waikoloa, HI Google Scholar