Patient Management Exercise for Genetics and Genomics

Abstract

This exercise is designed to test your comprehension of material presented in this issue of FOCUS as well as your ability to evaluate, diagnose, and manage clinical problems. Answer the questions below, to the best of your ability, on the information provided, making your decisions as you would with a real-life patient.

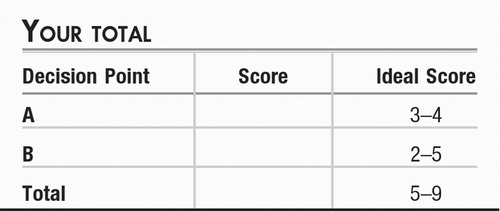

Questions are presented at “decision points” that follow sections that give information about the case. One or more choices may be correct for each question; make your choices on the basis of your clinical knowledge and the history provided. Read all of the options for each question before making any selections. You are given points on a graded scale for the best possible answer(s), and points are deducted for answers that would result in a poor outcome or delay your arriving at the right answer. Answers that have little or no impact receive zero points. At the end of the exercise, you will add up your points to obtain a total score.

CASE VIGNETTE PART 1

The possibility of using genetic data to help guide treatment decisions is an element of the paradigm of personalized medicine. In psychiatry, there is considerable evidence that genetic factors related to drug metabolism (“clinical pharmacogenomics”) may be useful in the selection of medication(s), as reviewed recently by Mrazek (1).

Alison is a 24-year-old woman who was referred to you by her primary care physician for the management of major depression. She had initially sought care there but has been referred for specialty care because she is still ill despite two trials of pharmacotherapy. The patient's chief complaint is “I'm still sad and crying all the time; why can't I feel better?”

Alison is a single woman of mixed European and Native American ancestry. She reported that she had a happy childhood and adolescence, growing up in an intact nuclear family, the eldest of three children. She reported that she had some periods of emotional turmoil while in college, usually related to the end of a romantic relationship, but these were all self-limited, and each time resolved within about 3 weeks. She is now pursuing graduate studies in political science and working part-time as a research assistant in her department. Her current episode began about 6 months ago, in the wake of a boyfriend moving out of town for work and ending their relationship; this time she was unable to “bounce back,” and she sought care with her primary care physician because she developed a large number of symptoms and started to have trouble with her academic obligations. Her present symptoms include depressed mood, insomnia, guilt-filled ruminations, loss of appetite with weight loss (about 15 pounds), low energy, difficulty concentrating on her studies and job, and dramatic curtailment of any pleasurable activities (including making up excuses not to go out with her circle of friends). She denied feeling any suicidal thoughts or impulses. Aside from these periods of distress after break-ups, she has no other history of emotional, behavioral, or other neuropsychiatric condition, including no history of substance use or of any other major axis I or axis II diagnosis. Review of systems revealed cyclic low back pain with menstrual cramping. Her family history is notable for breast cancer in an aunt and for the absence of any psychiatric diagnoses.

In the consultation request and chart notes, her primary care physician indicated that prior efforts with antidepressant medication trials have been unsuccessful. These included a trial of fluoxetine, for which she could not tolerate doses greater than 20 mg/day without profound nausea and anxiety; her maximum exposure was 20 mg/day for 4 weeks. She also tried venlafaxine but also found the dose was limited by tolerability concerns and felt “buzzy” with an uncomfortable level of agitation at 75 mg and higher; her maximum tolerable experience was 37.5 mg/day for 5 weeks. She was still taking that dose at her initial visit with you.

Decision Point A:

As you review her records and the data you gather at the initial evaluation visit, your thoughts include which of the following as likely reasons for her still being ill?

| A1._____ | Bipolar disorder instead of major depression as the diagnosis. |

| A2._____ | Inadequate therapeutic trials. |

| A3._____ | Covert substance use. |

| A4._____ | Secondary gain. |

CASE VIGNETTE PART 2

As you collected your own history and examination data, you asked about her experience with other medications. She told you that she often has to take “baby doses” of many medications and described that when she took an over-the-counter cold preparation a few years ago, she became “loopy” and it took a few days for that side effect to wear off; you asked and she clarified that it was probably one containing dextromethorphan. She also related that, in her teen years, she sprained her ankle in a sports accident and had to go back to her pediatrician for a different pain medication when “the codeine the ER [emergency room] doctor gave me didn't do a thing.”

Decision Point B:

What recommendation do you offer the patient at this point?

| B.1._____ | Offer a trial of augmenting the venlafaxine (still at 37.5 mg/day) with mirtazapine (starting with 15 mg/day). |

| B.2._____ | Draw a blood sample for genotyping. |

| B.3._____ | Refer her for psychotherapy. |

ANSWERS: SCORING, RELATIVE WEIGHTS, AND COMMENTS

Decision Point A:

| A1. | Depression as a part of bipolar disorder. (+1) Nonresponse to treatment can raise the question that the diagnosis is in error. Although clinical lore suggests that feeling a boost of energy with an selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor may increase one's suspicion that a person has bipolar disorder, this side effect is nonspecific and can be found in individuals with unipolar major depressive disorder as well. Had there been the presence of a family history of mood disorder, one's suspicion might have been somewhat sharpened, depending on the nature of the disorder in a relative, but the absence of a family history does not help with this differentiation. Common things happen commonly, and the prevalence of unipolar major depressive disorder is far greater than that of bipolar disorder. |

| A2. | Inadequate therapeutic trials. (+3) In STAR*D, it was found that half of the individuals who eventually had a remission with citalopram did so in 6 weeks or less, but that the other half took up to 12 weeks to cross the “finish line” of achieving remission (2). The Antidepressant Treatment History Form (3) is a common research tool used to assess the adequacy of past treatment trials. Intolerable side effect problems often can lead to abandoning a particular medication; here, the patient was able to persist with her maximal tolerated doses for many weeks, but dosing was limited by tolerability. |

| A3. | Covert substance use. (0) Many substances of abuse can produce depressive symptoms either during intoxication (e.g., sedative and hypnotic agents) or during withdrawal (e.g., psychostimulants). Although individuals in their 20s may be an at-risk age group for substance use, this patient's history and presentation allow you to put this far lower on the differential. |

| A4. | Secondary gain. (−1) As psychiatrists, we rely on self-report of our patients for data to make diagnoses and assess response to treatment. We also must rely on patients to be independently adherent to treatment when daily ingestion of a medication is concerned. A tactful approach is needed when one is probing patterns of adherence or psychosocial factors that might lead to persistence of symptoms to avoid disrupting the trust needed in a therapeutic relationship, whether the primary intervention is psychotherapeutic or pharmacological. We have no evidence that factors such as disability insurance, avoiding obligations by adopting the “sick role,” or other considerations are at play here. |

Decision Point B:

| B1. | Augmentation treatment. (+1) The patient has had trouble tolerating dose titration for two antidepressants but is able to take a low dose of venlafaxine. Based on findings in STAR*D (3) and other studies (4), you consider augmenting with mirtazapine, with thoughts to capitalize on their complementary putative mechanisms of action. You also hope that the effect profile of mirtazapine will help with her insomnia and weight loss. |

| B2. | Draw blood for genotyping. (+2) The history of medication intolerance for some medications and lack of efficacy for codeine makes you suspicious that the patient may carry genes that confer atypical drug metabolism. |

| B3. | Psychotherapy. (+2) Studies of cognitive behavior therapy have shown that this modality may have efficacy comparable to that of pharmacotherapy for some patients (5). Although physical side effects are not generally an issue with cognitive behavioral therapy, some individuals may find concerns that limit their ability to adhere to a treatment course, such as time demands, insurance coverage, and openness to a psychotherapeutic approach. |

|

CONCLUSIONS

Alison would have to pay out of pocket for psychotherapy, a financial stretch for a graduate student, so you and she agree that a trial of mirtazapine augmentation may help address her symptoms, including insomnia, and other aspects of her current distress. She calls after 3 days, saying that she has had to stop taking mirtazapine, because she was so sedated that she missed class.

You discuss over the phone the potential for genotyping, and your suspicion that she may not metabolize medications in a typical way. She has read a lot about the science of genetics in medical care and has a friend who sent her blood away for genotyping “out of curiosity” and is intrigued. She returns to your office for phlebotomy and formal genotyping. Phenotypically, she appears to be a “slow metabolizer” in the cytochrome P450 system 2D6 enzymatic pathway, which figures prominently in the metabolism of many medications; this would explain both her difficulty in tolerating medications that are substrates for 2D6 and the lack of efficacy of codeine, which must be converted from an inactive prodrug form by 2D6 to produce analgesia.

The results of her testing confirm that she has two inactive genes for CYP2D6. You discuss with her the option to treat her with a medication that is considerably metabolized by other hepatic enzymatic pathways. You also counsel her to tell future physicians that she is a “slow metabolizer for 2D6” and should not bother trying to use codeine for pain relief.

After a discussion of the risks, benefits, and side effects of several other treatments, she opts for sertraline and over the next few weeks you have her titrate to a dose of 150 mg/day. At that point, she finds that her symptoms are resolving, and, after 6 weeks, she reports that she is in remission, with a self-rated 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology score of 3.

1 Mrazek DA: Psychiatric pharmacogenomic testing in clinical practice. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2010; 12: 69– 76Google Scholar

2 Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M, STAR*D Study Team: Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006; 163: 28– 40Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Sackeim HA: The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62( suppl 16): 10– 7Google Scholar

3 McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Davis L, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Luther JF, Niederehe G, Warden D, Rush AJ: Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1531– 1541Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, Laberge L, Hebert C, Bergeron R: Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167: 281– 288Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT: The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev 2006; 26: 17– 31Crossref, Google Scholar