Diagnosis and Treatment of Sleep Disorders in Older Adults

Abstract

Among the most common complaints of older adults are difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep. These problems result in insufficient sleep at night, which then results in an increased risk of falls, difficulty with concentration and memory, and overall decreased quality of life. Difficulties sleeping, however, are not an inevitable part of aging. Rather, these sleep complaints are often secondary to medical and psychiatric illness, the medications used to treat these illnesses, circadian rhythm changes, or other sleep disorders. The task for the geriatric psychiatrist is to identify the causes of these complaints and then initiate appropriate treatment.

(Reprinted with permission from American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2006; 14:95–103)

Sleep complaints are common in all age groups. Older adults, however, are particularly vulnerable. In a study of over 9,000 community-dwelling adults over age 65 years, 42% of subjects reported difficulty in initiating and maintaining sleep (1). At follow up three years later, nearly 15% of the 4,956 participants without symptoms of difficulty sleeping at baseline reported chronic difficulty falling asleep or early-morning arousal, suggesting an annual incidence rate of approximately 5%. However, of the 2,000 survivors with chronic difficulties at baseline, approximately 50% no longer had symptoms. The discontinuation of insomnia symptoms was associated with improved self-perceived health (2). A recent comprehensive review by Ohayon (3) reported that in noninstitutionalized elderly respondents, difficulties initiating sleep were reported in 15% to 45%, disrupted sleep in approximately 20% to 65%, early-morning awakenings in 15% to 54%, and nonrestorative sleep in approximately 10%. In most studies, the prevalence of sleep disturbances and dissatisfaction with sleep did not significantly increase with age, but was higher in women than in men. A more complete review may be found in Ohayon (3).

Given that approximately half of older adults report difficulty sleeping, it is important to understand the causes of these complaints. First, however, it is necessary to understand normal changes in sleep that occur with age. Sleep is divided into two states, non-REM (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. NREM is further divided into four stages (stages 1, 2, 3, and 4) of sleep, with each stage getting progressively deeper. Sleep recordings of older adults, as compared with younger adults, have shown that older adults have less deep sleep (stages 3 and 4, also called slow-wave sleep) and less REM sleep. However, a recent meta-analysis looking at 65 studies, representing 3,577 subjects age five years to 102 years, suggested that these age-related sleep changes are already seen in young and middle-aged adults, with the percentage of slow-wave sleep linearly decreasing at a rate of approximately 2% per decade of age up to age 60 years. Studies that included only elderly participants did not find changes in percentage of slow-wave sleep. Rather, sleep remained relatively constant from age 60 to the mid-90s, except for sleep efficiency (defined as the amount of sleep, given the amount of time in bed), which continued to decrease. The meta-analysis also showed that as slow-wave sleep and REM sleep decreased, more of the night was spent in lighter stages of sleep, that is, stage 1 and stage 2 sleep (4).

Nevertheless, these changes in sleep architecture, on their own, do not account for most of the sleep complaints of the older adult. Rather, the sleep difficulties are, in part, a result of the older adults' decreased ability to maintain sleep. The causes of the decreased ability to maintain sleep are multifactorial and include the influence of medical and psychiatric illness and medications on sleep, changes in the timing and consolidation of sleep as a result of changes in the endogenous circadian clock, and the presence of other sleep disorders.

Sleep disturbances can have significant, serious consequences. Sleep problems are associated with increased risk of falls in the older adult, even after controlling for medication use, age, difficulty walking, difficulty seeing, and depression (5). Studies have shown that patients with difficulty sleeping reported poorer overall quality of life more frequently, as well as more symptoms of depression and anxiety, than those with no sleep difficulties. These patients were more likely to have slower reaction times, poorer balance, and worse memory than matched control subjects (6). Chronic sleep difficulties at any age can lead to deficits in attention, response times, short-term memory, and performance level (7). Also, cognitive functioning in older adults with sleep difficulties has been shown to be impaired, as compared with normal-sleeping control subjects, possibly secondary to deficits in slow-wave sleep (8). Diminished cognitive functioning may be particularly problematic in elderly persons because it may be mistaken for dementia.

Difficulty sleeping in elderly patients is also associated with morbidity. In a large epidemiologic study of older adults in the United States, difficulties with sleep were associated with poor health status (1). In the three-year follow up to this study, long-term persistence of insomnia was associated with heart disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease at baseline (2). In a second study, older adults with long sleep latencies, low sleep efficiency, and low amounts of REM sleep were at greater risk of all-cause mortality at a mean of 13-year follow up after controlling for age, gender, and baseline medical burden (9). Changes in both sleep quality and cognition may also lead to early institutionalization and loss of the ability to conduct normal daily activities (10, 11).

INSOMNIA

The common sleep complaints heard in the older adult are often diagnosed as insomnia. Insomnia is defined as difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep or having nonrestorative sleep, resulting in daytime dysfunction (12). Although insomnia may be a primary diagnosis, in the older adult, it is often co-morbid with medical and psychiatric illness, concomitant drug use, circadian rhythm changes, and other sleep disorders. These factors are described subsequently followed by sections on other sleep disorders.

MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESSES

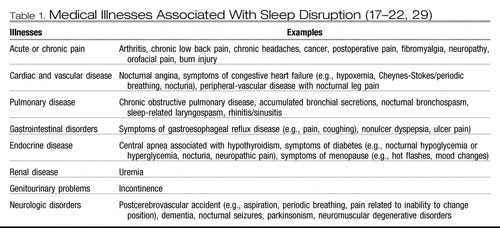

Studies have shown that insomnia is more common in patients with other comorbidities. Katz et al. (13), in a study of over 3,000 adults, found that between 30% and 50% of patients with myocardial infarctions, angina, congestive heart failure, hip replacement, diabetes, or prostate problems had insomnia. Klink et al. (14) examined the impact of comorbidities on insomnia, finding that insomnia was associated with having cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and other medical disorders. These data were recently confirmed in elderly subjects. In data on close to 5,000 older adults who were followed for up to four years, incidence of sleep disturbances (trouble falling asleep, frequent awakenings, and excessive daytime sleepiness) was related to depression, health conditions, and physical functioning. Persistence of the sleep disturbance at follow up, however, was best predicted by the presence of depression (15). In a survey of over 1,000 older adults age 65 years and over, more complaints of sleeping less than 6 hours per night, any insomnia, and excessive daytime sleepiness were associated with having heart disease, lung disease, a history of stroke, or depression. Also, having multiple conditions was related to having more sleep complaints (16). Studies examining the prevalence of sleep disturbances in chronic disease found the complaint of difficulty falling asleep in 31% of patients with arthritis and 66% of patients with chronic pain; difficulty staying asleep in 81% of patients with arthritis, 85% of patients with chronic pain, and 33% of patients with diabetes; and difficulty falling and staying asleep in 45% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease, 50% of patients with congestive heart failure, and 44% of patients with cancer (17–22). Table 1 lists some of the medical illnesses associated with sleep disruption.

Table 1. Medical Illnesses Associated With Sleep Disruption (17–22, 29)

As an example of how a medical illness can disrupt sleep, 74% to 98% of patients with Parkinson disease (PD) have sleep complaints (23). Some of the sleep problems arise from the disease process itself, that is, biochemical changes in the brain, dementia, bradykinesia and rigidity, tremor, and respiratory disturbances associated with airway and respiratory movements (24). PD causes pain in the legs and back, difficulties getting in and out of bed and turning in bed, and vivid dreams and nightmares. For a complete review of sleep problems in PD, see Abad et al. (24).

Insomnia is also related to psychiatric disorders. It is particularly common in mood disorders and may be a diagnostic symptom for major depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Using a cross-sectional telephone survey with over 24,000 adults (of all ages), Ohayon and Roth (25) found that insomnia was present in 65% of those with major depression, 61% of those with panic disorder, and 44% of those generalized anxiety disorder. Not only is insomnia common in patients with psychiatric disorders, but patients with insomnia are more likely to have a psychiatric disorder. Buysse et al. (26) found that a high proportion of patients with insomnia also have a psychiatric diagnosis. Also, insomnia at baseline significantly predicts an increased risk of depression at follow up one year to years later (27, 28).

MEDICATION USE

The same chronic conditions that cause sleep complaints often require long-term drug therapy that is also known to cause insomnia as a side effect (29). In general, sleep may be improved by adjusting the dosage of the medication or the time of day that these medications are taken. For example, alerting or stimulating drugs, when taken late in the day, may cause difficulty falling asleep at night. In particular, central nervous system stimulants (e.g., dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate), antihypertensives (e.g., beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, methyldopa, reserpine), respiratory medications (e.g., theophylline, albuterol), bronchodilators, calcium channel blockers, corticosteroids, decongestants (e.g., pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, phenylpropanolamine), stimulating antidepressants (e.g., protriptyline, bupropion, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], venlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs]), stimulating antihistamines, and hormones (e.g., corticosteroids, thyroid) are all known to contribute to insomnia. The older adult is often required to take many of these medications. On the other hand, sedating drugs such as the longer-acting sedative hypnotics, antihistamines, and sedating antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, doxepin, trimipramine, trazodone, mirtazapine) taken early in the day may lead to excessive daytime sleepiness and daytime napping behavior, which may contribute to sleep-onset insomnia or may further exacerbate and maintain existing insomnia. As an example, treatment of PD with low-to-moderate doses of dopamine agonists or antiparkinsonian agents may improve sleep by reducing rigidity and bradykinesia, but may also exacerbate or even create new sleep disturbances such as those secondary to visual hallucinations associated with L-dopa, nocturnal dystonia, and choreic movements.

CHANGES IN CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

Circadian rhythms are biologic rhythms that control many physiological functions. Examples of circadian rhythms are endogenous hormone secretions, core body temperature, and the sleep-wake cycle. Circadian rhythms are controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the anterior hypothalamus, which houses the internal circadian pacemaker; they are synchronized to the hour of the day by external zeitgeber time givers or cues such as light and other internal rhythms. For example, the sleep-wake cycle is synchronized by the internal core body temperature and endogenous melatonin cycle and by the external light-dark rhythm, which asserts its effect on the sleep-wake cycle through the retinohypothalamic visual pathway.

With age, the sleep-wake circadian rhythm becomes less synchronized, that is, it may no longer have the same response to external cues. The sleep-wake circadian rhythm becomes much weaker (less robust), resulting in less consistent periods of sleeping/waking across the 24-hour day. The sleep-wake cycle in the older adult also shifts, or advances. Changes in the sleep-wake cycle are likely the result of changes in the core body temperature cycle, decreased light exposure, and environmental factors. More recent research suggests that there may also be a genetic component (30, 31).

Patients with advanced rhythms often complain that their waking hours are no longer consistent with societal norms, causing them to be awake (or asleep) when those around them are not. They get sleepy in the early evening and wake up in the early morning hours, in part because the core body temperature is dropping earlier in the evening (perhaps at approximately 7:00 pm or 8:00 pm) and rising approximately eight hours later, at approximately 3:00 or 4:00 am. This leads to complaints of waking up in the middle of the night and being unable to return to sleep.

There are two common scenarios for those with advanced rhythms. In the first, the older adult, although tired early in the evening, tries to stay awake until a “more acceptable” bedtime, however, because of the advanced circadian rhythm, still wakes up in the early morning hours, thus not being in bed long enough to get sufficient sleep. In the second scenario, the older adult falls asleep while reading or watching TV in the early evening, and then, finally getting into bed, is unable to fall asleep because of that evening nap. Now the complaint becomes both difficulty falling asleep and difficulty staying asleep.

Advanced rhythms can be delayed by increasing light exposure later in the day, because bright light is the most influential external zeitgeber for the sleep-wake circadian rhythm (32).

TREATMENT OF INSOMNIA

Insomnia is generally treated with pharmacological therapy. The newer benzodiazepine receptor agonists (e.g., zolpidem, zaleplon, eszopiclone) have all been tested in older adults and have been shown to be effective and safe (33–36). A melatonin receptor agonist (e.g., ramelteon) has also been shown to be safe and effective in older adults (37).

A better approach to treating insomnia, however, is a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy. Behavioral therapies are used to modify maladaptive sleep habits, reduce autonomic and cognitive arousal, alter dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep, and educate patients about healthier sleep practices (38). Sleep complaints and disorders are often perpetuated, if not precipitated, by poor sleep habits (i.e., poor sleep hygiene). This could include spending too much time in bed; having an irregular sleep schedule; not getting sufficient bright-light exposure during the day; sleeping in an environment that is too bright, too noisy, or too hot or cold; and/or drinking alcohol or caffeinated beverages too close to bedtime.

The most effective approach to behavioral therapy is a type of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) that is a combination of stimulus control and/or sleep restriction plus cognitive restructuring, relaxation, and good sleep hygiene (38, 39). In a study of insomnia in older adults, CBT was compared with temazepam (7.5 mg–30 mg), a combination of both CBT and temazepam, and placebo. Results showed that immediately posttreatment (8 weeks), the three active treatments were all better than placebo in reducing wake time during the night. At 3-, 12-, and 24-month follow up, however, those treated with CBT maintained clinical gains, whereas the others did not (40).

The advantages of behavioral therapies are the durability and the lack of dependency or rebound insomnia. The disadvantages are that the clinical benefit may take two weeks or longer to appear, and the technique may require regular practice (38, 39), although, recently, an abbreviated CBT of two 25-minute sessions was successfully tested versus standard sleep hygiene and was effective in reducing wake time and normalizing insomnia symptoms (41).

The advantages of using a combination of pharmacologic and behavior therapies is that the pharmacologic therapy offers short-term respite during the period before benefits of behavior therapies appear but combined with the durability of the CBT. The disadvantage is that clinical gains may not be maintained long-term if the attribution of the sleep improvements is made to the drug alone, thus undermining the development of appropriate coping skills (38).

PERIODIC LIMB MOVEMENTS IN SLEEP AND RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME

Periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) is characterized by clusters of repeated leg jerks occurring approximately every 20–40 seconds over the course of the night with each jerk causing a brief awakening. A diagnosis is made when there are at least five kicks per hour of sleep, each causing an arousal. The prevalence of PLMS in older adults is estimated at 45%, versus 5%–6% in younger adults (42, 43). There is no gender difference. Another disorder, often comorbid with PLMS, is restless leg syndrome (RLS). RLS is characterized by dysesthesia in the legs, usually described by patients as “a creeping, crawling sensation” or as “pins and needles,” which can only be relieved with movement (44). These sensations often occur whenever the patient is in a restful, relaxed state. RLS increases significantly with age, with women being twice as often affected as men (42, 43, 45). One epidemiologic study of 19,000 adults found that age was a risk factor for RLS but not for PLMS (46). There has been considerable recent debate in the sleep literature as to whether PLMS independent of RLS indeed constitutes a diagnosable disorder. More research will need to be done to determine the significance of kicks during sleep.

The most common complaints of patients with PLMS and RLS are difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness. Patients may or may not be aware of their leg jerks. Some may report simply having difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep with no knowledge that they kick. Bed partners, however, are often aware of the leg movements and may have moved into separate beds. Those with both PLMS and RLS may also report uncomfortable sensations in their legs during the day. Patients with symptoms of RLS should be assessed for anemia, uremia, and peripheral neuropathy before treatment.

There are several pharmacologic treatments for PLMS and RLS that target the leg movements and/or the associated arousals. The only FDA approved medication for RLS is ropinirole, however, other dopamine agonists (e.g., pergolide and pramipexol) have been successfully used off-label, as they all reduce or eliminate both the limb jerks and the associated arousals (47, 48).

RAPID EYE MOVEMENT BEHAVIOR DISORDER

REM behavior disorder (RBD) is characterized by complex motoric behaviors occurring during REM sleep, most likely resulting from an intermittent lack of the skeletal muscle atonia typically present during REM sleep. RBD usually occurs during the second half of the night, when REM is more prevalent. The patient may engage in complex motoric behaviors during sleep such as vigorous and complex body movements and actions. Movements may be violent and may harm the patient and/or the patient's bed partner. Often, the person may be unable to recollect these actions in the morning. RDB spans various age groups but is more prevalent in older men (24).

The etiology of RBD is unknown. Some reports have suggested acute RBD is associated with the intake of tricyclic antidepressants, fluoxetine, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and withdrawal from alcohol or sedatives. In contrast, chronic RBD has been associated with narcolepsy and other idiopathic neurodegenerative disorders such as dementia with Lewy bodies and PD (for a complete review, see Montplasir (49).

RBD is generally treated with clonazepam, which acts by inhibiting nighttime motoric movements without directly affecting muscle tone (50). This results in partial or complete cessation of abnormal body movements during the night in 90% of patients with RBD. However, the symptoms return when treatment is discontinued.

SLEEP-DISORDERED BREATHING

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is characterized by hypopneas (partial respiration) and/or apneas (complete cessation of respiration) during sleep. The number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep is called the “apnea-hypopnea index” (AHI). Clinical diagnosis of SDB is traditionally given when a patient has an AHI ≥ 10–15. The cessations in breathing in SDB lead to repeated arousals from sleep as well as reductions in blood-oxygen levels over the course of the night, resulting in nighttime hypoxemia.

SDB is more common in older than younger adults. The prevalence of SDB is approximately 4%–9% in middle-aged men and women (age 30–60 years) versus 45%–62% in older adults (60+ years) (51, 52). The Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) has recently examined the occurrence of SDB in several thousand adults aged 40–98 years. Results from the SHHS confirm that the prevalence of having an AHI ≥15 in this nonrandom sample of adults increased with age, with approximately 20% of those aged 60 or older meeting this criterion versus approximately 10% in 45-year-old subjects (53).

There is some discussion in the literature, however, about the significance of sleep apnea in the older adult, whether it is the same phenomenon as SDB in the younger adult and whether it should be treated. In general, if an older adult has cardiac disease, hypertension, nocturia, cognitive dysfunction, or severe SDB, treatment should be considered (54).

The main symptoms of SDB are snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness, although, as age increases, the association between SDB and body mass index and reports of snoring and respiratory pauses in sleep decreases (53). The snoring is reflective of the airway collapse and is a component of the breathing cessation during an apneic event. It is often extremely loud and can be heard throughout the house. The loud snoring sometimes forces bed partners to sleep in a separate bedroom.

The excessive daytime sleepiness in SDB has been associated with both repeated nighttime awakenings, which frequently follow the apneic events, and with intermittent nighttime hypoxemia. Daytime sleepiness most often manifests as falling asleep at inappropriate times during the day. Patients with excessive daytime sleepiness secondary to SDB may fall asleep while reading, watching TV, at the movies, in conversation with a group of friends, or while driving. Daytime sleepiness can be a very debilitating symptom, causing social and occupational difficulties, reduced vigilance, and cognitive deficits, including decreased concentration, slowed response time, and memory and attention difficulties. These symptoms may be particularly relevant to older adults, who are at an increased risk of developing such symptoms with aging. SDB may unnecessarily further exacerbate these cognitive deficits. SDB is a risk factor for other health problems, including hypertension and cardiac and pulmonary problems, (55, 56), which can then lead to increased risk of mortality (57–59).

The most common treatment for SDB is positive airway pressure (60). There are several types of devices that provide positive airway pressure, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), and Auto-CPAP. CPAP provides continuous air pressure through a hose connected to a nose mask. The air pressure acts as a splint to maintain the opening of the upper airway, thereby preventing the obstruction or collapse of the airway. The degree of air pressure depends on the patient's apnea severity (traditionally 5–20 cm H2O) and is set individually for each patient at the sleep laboratory.

SLEEP PROBLEMS IN DEMENTIA

Sleep disturbances are also common in patients with dementia. Cross-sectional studies of clinicbased or community samples report that 19%–44% of patients have disruptions in their sleep (61). Increased duration and frequency of awakenings, decreased SWS and REM sleep, and daytime napping mark the sleep of patients with dementia (62). Sleep disturbances observed in patients with dementia occur more frequently and tend to be more severe than in older adults without dementia (63). In one study, the factors most strongly associated with nighttime awakenings were male gender, greater memory problems, and decreased functional status (64). Sleep disturbances in patients with dementia are a significant source of physical and psychologic stress for the caregiver and are related to patient institutionalization (11, 62, 65). A recent study found that behavioral techniques may be viable treatments of sleep problems not only in the patient, but also in caregivers of patients with dementia (66).

The sleep of patients with severe dementia living in nursing homes is known to be extremely disturbed and severely fragmented. One study determined that often there is not a single hour in a 24-hour day that is spent fully awake or asleep (67–69). Environmental factors in the nursing home may also contribute to reduction in the quality of sleep. Noise and light exposure occurs intermittently throughout the night and contributes to the sleep disruption. Institutionalized patients spend a significant amount of the 24-hour day in bed, leading to rapid cycling between sleep and waking during this time. Changes in sleep hygiene and the sleep environment of nursing home patients may greatly improve the sleep quality in this population (70, 71).

Managing sleep problems in the elderly person with dementia remains challenging. Sedative-hypnotics and antipsychotics are often used but have many associated problems as a result of exacerbation of insomnia and dementia symptoms and side effects (72). Nonpharmacologic treatment with bright-light therapy has been shown to consolidate sleep (73, 74). Other treatments such as restricting time in bed, increased physical activity, and improving the environment are all now being explored as treatment approaches for use with this population (73–76).

SUMMARY

Sleep in the older adult becomes lighter with age. However, healthy older adults rarely have sleep complaints (16). In a study of several thousand older adults, 57% had chronic insomnia, versus 12% with no insomnia, but the chronic insomnia was more prevalent among those with depressed mood, respiratory symptoms, fair-to-poor health, and physical disability (1). Foley et al. (2) concluded that aging, per se, does not cause the sleep disturbances. Rather, the sleep disruptions seen in this population are secondary to other factors, or co-morbid with medical and psychiatric illness, medication use, circadian rhythm changes, and other sleep disorders such as SDB and RBD. Healthcare professionals working with the geriatric population need to learn to differentiate the different causes of sleep disturbances in this population so that appropriate therapy can be initiated.

1 Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, et al: Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep 1995; 18: 425– 432Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Foley DJ, Monjan A, Simonsick EM, et al: Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: an epidemiologic study of 6,800 persons over 3 years. Sleep 1999; 22: S366– S372Google Scholar

3 Ohayon MM: Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev 2002; 6: 97– 111Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, et al: Metaanalysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep 2004; 27: 1255– 1273Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Brassington GS, King AC, Bliwise DL: Sleep problems as a risk factor for falls in a sample of community-dwelling adults age 64–99 years. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: 1234– 1240Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Hauri PJ: Cognitive deficits in insomnia patients. Acta Neurol Belg 1997; 97: 113– 117Google Scholar

7 Walsh JK, Benca RM, Bonnet M, et al: Insomnia: assessment and management in primary care. Am Fam Physician 1999; 59: 3029– 3037Google Scholar

8 Crenshaw MC, Edinger JD: Slow-wave sleep and waking cognitive performance among older adults with and without insomnia complaints. Physiol Behav 1999; 66: 485– 492Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Dew MA, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, et al: Healthy older adults' sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosom Med 2003; 65: 63– 73Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Tinetti ME, Williams CS: Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1270– 1284Google Scholar

11 Gaugler JE, Edwards AB, Femia EE, et al: Predictors of institutionalization of cognitively impaired elders: family help and the timing of placement. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000; 55: 247– 255Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

13 Katz DA, McHorney CA: Clinical correlates of insomnia in patients with chronic illness. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 1099– 1107Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Klink ME, Quan SF, Kaltenborn WT, et al: Risk factors associated with complaints of insomnia in a general adult population: influence of previous complaints of insomnia. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152: 1634– 1637Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Quan SF, Katz R, Olson J, et al: Factors associated with incidence and persistence of symptoms of disturbed sleep in an elderly cohort: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Med Sci 2005; 329: 163– 172Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, et al: Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res 2004; 56: 497– 502Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Wilcox S, Brenes GA, Levine D, et al: Factors related to sleep disturbance in older adults experiencing knee pain or knee pain with radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: 1241– 1251Crossref, Google Scholar

18 McCraken LM, Iverson GL: Disrupted sleep patterns and daily functioning in patients with chronic pain. Pain Res Manag 2002; 7: 75– 79Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Savard J, Morin CM: Insomnia in the context of cancer: a review of a neglected problem. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 895– 908Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J: Sleep complaints predict coronary artery disease mortality in males: a 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged Swedish population. J Intern Med 2005; 251: 207– 216Google Scholar

21 Klink M, Quan SF: Prevalence of reported sleep disturbances in a general adult population and their relationship to obstructive-airway diseases. Chest 1987; 91: 540– 546Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Sridhar GR, Madhu K: Prevalence of sleep disturbance in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1994; 23: 183– 186Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, Bravo M: Parkinson's disease and sleep. Sleep Med Rev 2003; 7: 115– 129Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Abad VC, Guilleminault C: Review of rapid eye movement behavior sleep disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2004; 4: 157– 163Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Ohayon MM, Roth T: What are the contributing factors for insomnia in the general population? J Psychosom Res 2001; 51: 745– 755Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Kupfer DJ, et al: Clinical diagnoses in 216 insomnia patients using the international classification of sleep disorders (ICSD), DSM-IV, and ICD-10 categories: a report from the APA/NIMH DSM-IV field trial. Sleep 1994; 17: 630– 637Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Riemann D, Voderholzer U: Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord 2003; 76: 255– 259Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Fava M: Daytime sleepiness and insomnia as correlates of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65: 27– 32Google Scholar

29 Ancoli-Israel S: Insomnia in the elderly: a review for the primarycare practitioner. Sleep 2000; 23: S23– S30Google Scholar

30 Ancoli-Israel S, Schnierow B, Kelsoe J, et al: A pedigree of one family with delayed sleep phase syndrome. Chronobiol Int 2001; 18: 831– 841Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Jones CR, Campbell SS, Zone SE, et al: Familial advanced sleepphase syndrome: a short-period circadian-rhythm variant in humans. Nature Med 1999; 5: 1062– 1065Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Klerman EB, Duffy JF, Dijk DJ, et al: Circadian-phase resetting in older people by ocular bright-light exposure. J Investig Med 2001; 49: 30– 40Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Ancoli-Israel S, Walsh JK, Mangano RM, et al: Zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic, effectively treats insomnia in elderly patients without causing rebound effects. Prim Care 1999; 1: 114– 120Google Scholar

34 Ancoli-Israel S, Richardson GS, Mangano R, et al: Long-term use of sedative-hypnotics in older patients with insomnia. Sleep Med 2005; 6: 107– 113Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Roger M, Attali P, Coquelin JP: Multicenter, double-blind, controlled comparison of zolpidem and triazolam in elderly patients with insomnia. Clin Ther 1993; 15: 127– 136Google Scholar

36 Scharf MB, Mayleben DW, Kaffeman M, et al: Dose-response effects of zolpidem in normal geriatric subjects. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52: 77– 83Google Scholar

37 Roth T, Stubbs C, Walsh JK: Ramelteon (TAK-375), a selective MT1/MT2-receptor agonist, reduces latency to persistent sleep in a model of transient insomnia related to a novel sleep environment. Sleep 2005; 28: 303– 307Google Scholar

38 Morin CM, Hauri PJ, Espie CA, et al: Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep 1999; 22: 1134– 1156Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Sateia MJ: Insomnia. Lancet 2004; 364: 1959– 1973Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, et al: Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia. JAMA 1999; 281: 991– 999Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Edinger JD, Sampson WS: A primary care-‘friendly’ cognitive-behavioral insomnia therapy. Sleep 2003; 26: 177– 182Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al: Periodic limb movements in sleep in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep 1991; 14: 496– 500Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Phillips BA, Young T, Finn L, et al: Epidemiology of restless legs symptoms in adults. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 2137– 2141Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Walters AS, Aldrich MS, Allen R, et al: Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 1995; 10: 634– 642Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, et al: Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 196– 202Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Ohayon MM, Roth T: Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53: 547– 554Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Littner M, Kushida C, Anderson WM, et al: Practice parameters for the dopaminergic treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep 2004; 27: 557– 559Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Hening W, Allen RP, Picchietti DL, et al: An update on the dopaminergic treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep 2004; 27: 560– 583Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Montplaisir J: Abnormal motor behavior during sleep. Sleep Med 2004; 5: S31– S34Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Schenck CH, Mahowald MW: Polysomnographic, neurologic, psychiatric, and clinical outcome report on 70 consecutive cases with the REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD): sustained clonazepam efficacy in 89.5% of 57 treated patients. Cleve Clin J Med 1990; 57: S10– S24Google Scholar

51 Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al: The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 1230– 1235Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al: Sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep 1991; 14: 486– 495Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Gozal D: Morbidity of obstructive sleep apnea in children: facts and theory. Sleep Breath 2001; 5: 35– 42Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Pack Al, Maislin G: Who should get treated for sleep apnea? Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 1065– 1067Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Nieto FJ, Young T, Lind B, et al: Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large, community-based study. JAMA 2000; 283: 1829– 1836Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Newman AB, Nieto FJ, Guidry U, et al: Relation of sleep-disordered breathing to cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 154: 50– 59Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Ancoli-Israel S, DuHamel ER, Stepnowsky C, et al: The relationship between congestive heart failure, sleep-disordered breathing, and mortality in older men. Chest 2003; 124: 1400– 1405Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al: Morbidity, mortality, and sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep 1996; 19: 277– 282Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Fell RL: Sleep-disordered breathing: preliminary natural history and mortality results, in International Perspective on Applied Psychophysiology. Edited by Seifert RA, Carlson J. New York, Plenum, 1994, pp 103– 111Google Scholar

60 Grunstein RR: Nasal continuous airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 1995; 50: 1106– 1113Crossref, Google Scholar

61 McCurry SM, Reynolds CF III, Ancoli-Israel S, et al: Treatment of sleep disturbances in Alzheimer's disease. Sleep Med Rev 2000; 4: 603– 628Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Vitiello MV, Borson S: Sleep disturbances in patients with Alzheimer's disease. CNS Drugs 2001; 15: 777– 796Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Vitiello MV, Prinz PN, Williams DE, et al: Sleep disturbances in patients with mild-stage Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1990; 45: M131– M138Crossref, Google Scholar

64 McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, et al: Characteristics of sleep disturbance in community-dwelling Alzheimer's disease patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12: 53– 59Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A: Determinants of carer stress in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 13: 248– 256Crossref, Google Scholar

66 McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Vitiello MV, et al: Successful behavioral treatment for reported sleep problems in elderly caregivers of dementia patients: a controlled study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998; 53: 122– 129Google Scholar

67 Jacobs D, Ancoli-Israel S, Parker L, et al: Twenty-four hour sleep-wake patterns in a nursing home population. Psychol Aging 1989; 4: 352– 356Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Pat-Horenczyk R, Klauber MR, Shochat T, et al: Hourly profiles of sleep and wakefulness in severely versus mild-moderately demented nursing home patients. Aging Clin Exp Res 1998; 10: 308– 315Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Ancoli-Israel S, Parker L, Sinaee R, et al: Sleep fragmentation in patients from a nursing home. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1989; 44: M18– M21Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Ancoli-Israel S, Jones DW, McGuinn P, et al: Sleep disorders, in Quality Care for the Nursing Home. Edited by Morris J, Lipshitz J, Murphy K, et al. St. Louis, MO, Mosby Lifeline, 1997, pp 64– 73Google Scholar

71 Alessi CA, Schnelle JF: Approach to sleep disorders in the nursing home setting. Sleep Med Rev 2000; 4: 45– 56Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Lenzer J: FDA warns about using antipsychotic drugs for dementia. BMJ 2005; 330: 922Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Ancoli-Israel S, Gehrman PR, Martin JL, et al: Increased light exposure consolidates sleep and strengthens circadian rhythms in severe Alzheimer's disease patients. Behav Sleep Med 2003; 1: 22– 36Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Ancoli-Israel S, Martin JL, Kripke DF, et al: Effect of light treatment on sleep and circadian rhythms in demented nursing home patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 282– 289Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Ancoli-Israel S, Poceta JS, Stepnowsky C, et al: Identification and treatment of sleep problems in the elderly. Sleep Med Rev 1997; 1: 3– 17Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Alessi CA, Yoon EJ, Schnelle JF, et al: A randomized trial of a combined physical activity and environmental intervention in nursing home residents: do sleep and agitation improve? J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47: 784– 791Crossref, Google Scholar