Definitions and Predictors of Successful Aging: A Comprehensive Review of Larger Quantitative Studies

Abstract

Objective:

There is no consensual definition of “successful aging.” Our aim was to review the literature on proportions of subjects meeting criteria and individual components of definitions of successful aging as well as correlates of these definitions. Methods: We conducted a literature search for published English-language peer-reviewed reports of data-based studies of adults over age 60 that included an operationalized definition of successful aging. The authors categorized the components of these definitions and independent variables examined in relation to successful aging (e.g., gender, education, and social contacts). Results: The authors identified 28 studies with 29 different definitions that met our criteria. Most investigations used large samples of community-dwelling older adults. The mean reported proportion of successful agers was 35.8% (standard deviation: 19.8) but varied widely (interquartile range: 31%). Multiple components of these definitions were identified, although 26 of 29 included disability/physical functioning. The most frequent significant correlates of the various definitions of successful aging were age (young-old), nonsmoking, and absence of disability, arthritis, and diabetes. Moderate support was found for greater physical activity, more social contacts, better self-rated health, absence of depression and cognitive impairment, and fewer medical conditions. Gender, income, education, and marital status generally did not relate to successful aging. Conclusion: Despite variability among definitions, approximately one-third of elderly individuals were classified as aging successfully. The majority of these definitions were based on the absence of disability with lesser inclusion of psychosocial variables. Predictors of successful aging varied yet point to several potentially modifiable targets for increasing the likelihood of successful aging.

(Reprinted with permission from American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2006; 14:6–20)

The past century has witnessed a doubling of the human lifespan, remarkable developments in research methods, and advances in health care. The systematic study of successful aging, or the capacity of elderly people to thrive, has, however, been a more recent phenomenon (1–5). Empiric investigations of healthy aging question the popular notion that aging invariably involves a decline in functioning and quality of life, and point toward factors that can increase individuals' “health span” as they enter later life (6, 7). However, at present, there is little agreement about the optimal definition of successful aging nor its measurement (1, 3, 4, 8) despite a clear need for consensus to facilitate effective promotion of public healthy-aging agendas (8).

The World Health Organization (9), the White House Conference of Aging (10), and the National Institute of Aging (11) have stressed that healthy aging goes beyond avoidance of disease and disability. Yet, further agreement on what factors constitute successful aging is surprisingly limited. The prevailing model, advanced by Rowe and Kahn and used in the MacArthur Research Network on Successful Aging (6, 12), characterizes successful aging as involving freedom from disability along with high cognitive, physical, and social functioning. Other ways of defining successful aging involve the degree to which elderly individuals adapt to age-associated changes (13, 14), view themselves as successfully aging (15), or avoid morbidity until the latest time point before death (7). There is considerable debate as to which components are essential to the definition of successful aging and which are overly restrictive or even possibly “ageist” (16,17). Furthermore, there is no consensus about whether successful aging should be defined objectively by others or subjectively by older adults themselves or about which components are necessary and/or sufficient (1,4). There is even no agreement about the term to be used, with descriptors ranging from “healthy aging” (2), “successful aging” (6, 13), “productive aging” (18), to “aging well” (19).

Previous reviews on this subject have examined the history of the concept (1, 3, 20), the prevalence of successful aging (21), its components (4), and/or its determinants (2, 4). We restricted our search to data-based studies that examined successful aging as a dependent variable as in Peel et al. (21) and evaluated the factors that influence the reported proportion of successful agers. We also categorized and examined the frequency and measurement of the various components used in these definitions. Although Peel et al. (2) reviewed the behavioral predictors (e.g., smoking) of successful aging, no reviews to our knowledge have systematically examined the strength and consistency of the demographic, psychosocial, and biomedical correlates of successful aging as an operationally defined, dependent variable. Finally, we examined the methodological issues that contribute to variability across studies in an effort to identify potential barriers to advancing this critical field. We hope that this review will introduce geriatric psychiatrists to the empiric literature on successful aging, highlighting methodological issues, summarizing the state of the evidence, and providing recommendations for future research

METHOD

DATA SOURCES

We searched the following databases: PubMed and www.scholar.google.com using the following terms: successful aging/aging, healthy aging/aging, productive aging/aging, optimal aging/aging, aging/aging well. Next, we used the “related articles” function on the PubMed web site and examined reference lists from published articles to obtain additional papers.

SELECTIONS OF DEFINITION OF SUCCESSFUL AGING

We restricted this search to only those articles that were published in English in peer-reviewed journals that met the following criteria: 1) Reported quantitative data from adults over age 60; and 2) Used an operationalized definition of successful aging as a continuous or categorical dependent variable. We did not restrict our search to definitions that had more than one component, like in some previous reviews on this subject (2, 21); we included studies that expressed an intent to study positive outcomes in aging.

CORRELATES/PREDICTORS OF SUCCESSFUL AGING

Among studies that reported correlates of successful aging, we assessed both cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of successful aging. We determined the frequency of predictor variables that were significant in relation to the different definitions (markers) of successful aging separately examining consistency among predictors across the various definitions. When available, we reported odds ratios for associations of independent variables. We categorized variables as demonstrating an association if the 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio did not include one (22). When multiple analyses with different numbers of control variables were presented, we reported the analysis with the most complete model tested. When correlates were presented separately for men or women (23) or in different levels (e.g., levels of physical activity (24)), we reported the range of odds ratios and the lowest and highest values in the confidence intervals. We categorized the predictor variable as mixed/nonsignificant if 1 was included in this range. Finally, in longitudinal reports when separate analyses were reported comparing successful agers with survivors and all cases (25), we reported the values for the comparison to survivors (given that only a few studies included comparisons with deceased participants).

RESULTS

Our database search of English-language articles from PubMed yielded 407 articles for “successful aging,” 490 articles for “healthy aging 12 for “productive aging,” one for “aging well” or “robust aging” (We also found 51 articles for successful aging and 91 for healthy aging.). Duplicate articles from these searches were eliminated; reviews were excluded (N = 192), as were qualitative studies on successful aging (N = 9) and those that included adults younger than age 60 (N = 2). After also examining reference lists from previous reviews,(1–4, 21) using related articles functions on PubMed and www.scholar.google.com, and adding two papers in press in the The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, we found 28 articles that met our search criteria. One article provided two definitions (16) so that there were 29 total definitions. Studies were published between 1978 and 2005. Mean sample size in the studies reviewed was 1,984 (standard deviation [SD]: 2,161; median: 1,045, range: 155–8,000). Twenty-seven reports included a categorical definition of successful aging and two used a continuous measure. A number of the samples used in these reports were large longitudinal, epidemiologic cohorts of older adults that have been used in multiple other publications not necessarily related to successful aging (e.g., Alameda County Study (16, 26), Cardiovascular Health Study (24), Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (27)). These were community samples of older adults, although some samples included institutionalized persons (23, 25, 28), whereas some specifically excluded them (24, 29, 30). Some studies excluded individuals if they could not provide a proxy(31, 32).

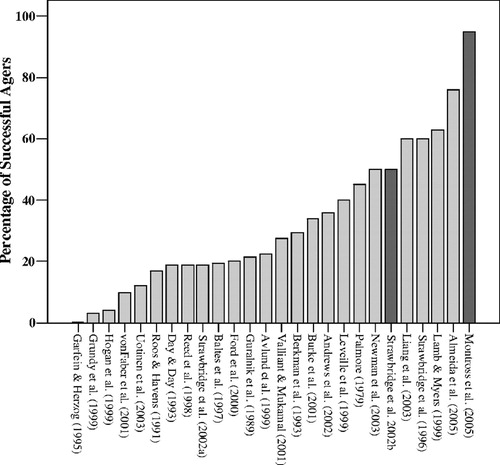

Of the 27 studies that included categoric operationalized definitions, mean sample size-weighted proportion of successful agers was 35.8% (SD: 19.8, median: 34.0) (Figure 1). The range of proportion of successful agers varied greatly, from 0.4% (33) to 95% (34). The interquartile range was 31% (19%–50%). The proportion of successful agers was inversely rated to the minimum age criterion of the study samples (ranging from age 60–85; r = −0.526, p <0.001) and the number of components in the definitions (ranging from 1–6, r = −0.726, p <0.001).

Figure 1. Reported Proportion of Successful Aging by Study

COMPONENTS OF SUCCESSFUL AGING DEFINITIONS

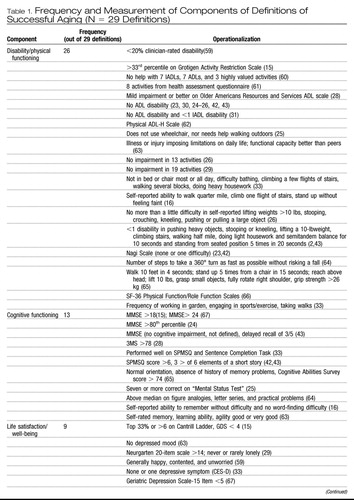

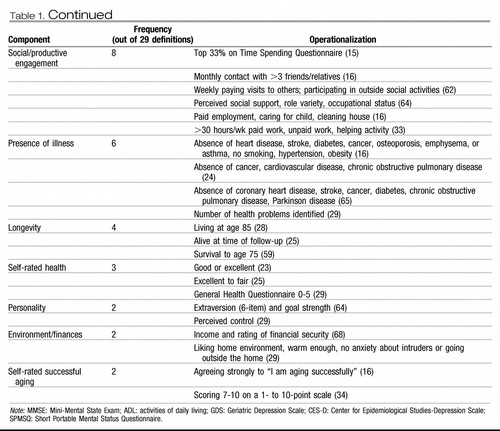

We categorized the components of these definitions into 10 different domains, each measured in varied manner from self-report to performance-based and other objective indicators (Table 1). The average number of components per definition was 2.6 (SD: 0.4, range: 1–6). The most frequently appearing component was disability and/or physical functioning (26 of 29), generally measured by self-reported activities of daily living (ADLs) and less often instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), objective performance (e.g., ability to walk a quarter mile; grip strength). The next most frequent component was cognitive functioning (13 definitions). Cognitive functioning was frequently gauged with cognitive screening tests (e.g., Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]) or self-reported memory functioning. Social and productive functioning was used in eight definitions and life satisfaction/well-being included in nine.

|

|

Table 1. Frequency and Measurement of Components of Definitions of Successful Aging (N = 29 Definitions)

Among the 22 studies that had disability/physical function in their definitions and reported a proportion of successful agers, the mean proportion was 27.2% (SD: 18.7; median: 20.8, range: 0.4–63.0) and among the four studies that did not include disability/physical function, the mean proportion was 63.8% (SD: 27.1; median: 63.0; range: 34.0–95.0). A smaller difference in proportions was observed between studies that used cognitive functioning (mean: 25.5, SD: 21.9, N = 11; median: 19.0; range: 0.40–76.0) and those that did not (mean: 38.2%, SD: 24.3, N = 15; median: 34.0; range: 3.0–95.0). The mean proportion of successful agers among studies that included both cognitive and disability/physical function was 20.4 (SD: 14.8, median: 19.0, range: 0.40–49.9); half that of those that included neither (mean: 40.5, SD: 25.3, median: 37.1, range: 3–95.0).

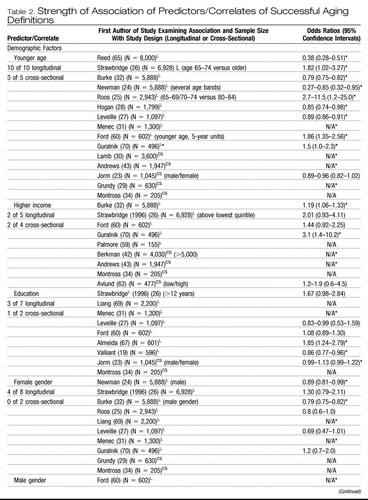

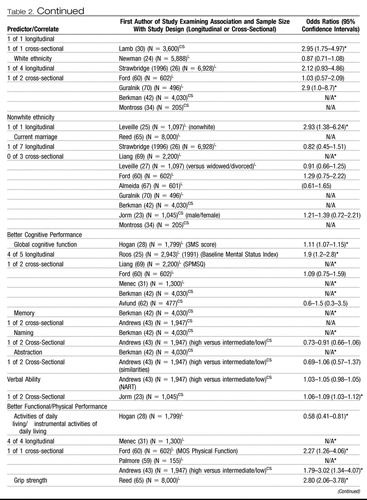

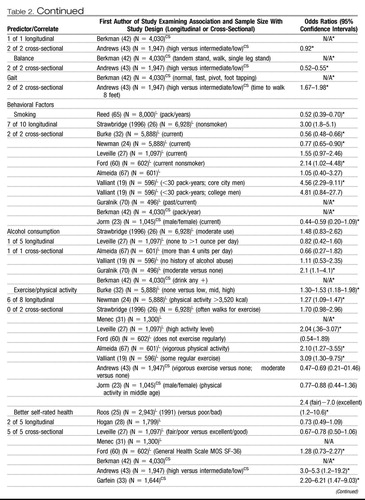

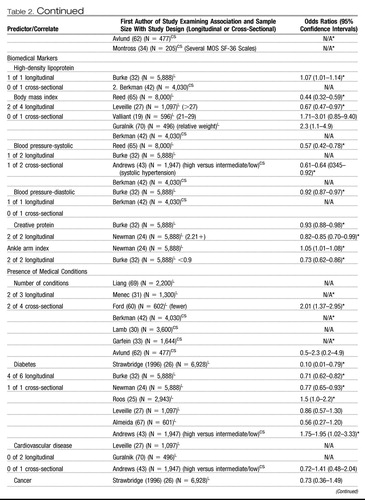

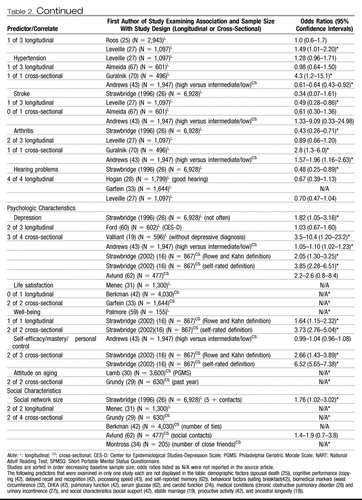

PREDICTORS OF SUCCESSFUL AGING

A number of independent variables were examined for their relationship to successful aging as the dependent variable (Table 2). Across the various definitions, the frequency of significance of predictor variables was assessed in relation to the different definitions of successful aging separately. Effect sizes (i.e., odds ratios) reported in Table 1 varied depending on: 1) the characteristics of the comparison group relative to the successfully aging group (e.g., diseased, all other subjects, both); 2) the variable definition (e.g., current smoking versus pack-years of smoking); 3) the other variables entered into the equation either simultaneously or as control variables; and 4) the time of measurement relative to the measurement of the successful aging construct, contemporaneous or longitudinal. Furthermore, studies most commonly reported odds ratios, yet some reported relative risk ratios or means and standard deviations.

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2. Strength of Association of Predictors/Correlates of Successful Aging Definitions

Despite differences in methods used, several interesting trends emerged. We defined evidence for predictors/correlates as “strong” if there were four or more studies reporting them and 75% or more found a significant association. The most consistent predictor of successful aging was younger age (i.e., closer to age 60) with 13 of 15 studies reporting a significant relationship with younger age to the probability of successful aging. Other “strong” predictors were related to health such as absence of arthritis (three of four), hearing problems (four of four), better activities of daily living (five of five), and not smoking (nine of 12).

“Moderate” support, which we defined as 50%-75% of four or more studies, was found for higher exercise/physical activity level (six of 10), better self-rated health (seven of 10), lower systolic blood pressure (two of four), fewer medical conditions (four of seven), global cognitive function (five of seven), and absence of depression (five of seven). “Limited” evidence, defined as the minority (<50%) of four or more studies, was found for higher income (four of nine), greater education (four of nine) current marriage (one of 10), and white ethnicity (two of seven). In addition, gender was inconsistent across reports. In general, other psychologic variables, biomedical markers, and social/productive activities were examined in too few studies to measure their strength.

DISCUSSION

We found considerable variability among the studies of successful aging in the proportion of subjects meeting operationally defined criteria, the domains that constituted definitions, how these domains were measured, and in the independent variables examined in relation to successful aging. Nonetheless, most investigations based their definitions, in part, on absence of physical disability/physical performance and, to a lesser extent, on absence of cognitive impairment. Approximately one-third of the elderly subjects sampled met researchers' criteria for successful aging. We found fairly consistent relationships between successful aging and younger age (i.e., being “young-old”), not smoking, physical activity, better self-rated health, and not having diabetes, arthritis, or cognitive impairment, and few relationships with demographic predictors.

The reported proportion of successful agers ranged from 0.4%–95%. Several methodological issues contribute to this variability. One source is the definitions. Similar to Phelan and Larson, (4) we identified several unique components within these definitions. Outside of disability/physical functioning and cognitive functioning, domains were varied, including subjective health and well-being, social functioning, and personality characteristics. Thus, variability in proportion of successful agers was partially attributable to differences in content (and number) of components. Not all articles reported proportions meeting criteria for individual components; however, articles that did not include disability/physical function in their definition reported higher proportions of successful agers.

Another source of variability was the sampling and measurement of successful aging. Studies differed in the “unsuccessful” group that the successful agers were compared with such as all others in the sample or an impaired group. However, most studies did not take into account the effect of mortality and, as such, only provide insight into factors that influence successful aging among survivors. Therefore, a predictor variable (e.g., gender) may not be associated with successful aging in this review, although that predictor may strongly relate to longevity. Although a majority of samples were large community cohorts, some restricted sampling to noninstitutionalized elders, and others included only those who could provide a proxy informant. In addition, studies varied as to whether successful aging was categorized based on cutoffs (e.g., no ADL disability) or percentiles of the sample (e.g., percentile on a disability scale). Thus, even comparing studies within domains (e.g., cognitive functioning) indicated by the same measure (e.g., MMSE) was difficult.

A final cause of variability may be a bias toward studying negative outcomes. A majority of the reports were designed to study the development of pathology or functional impairment in aging such as cardiovascular system (32) and not maintenance of positive or desirable states. Some measures used had ceiling effects (e.g., MMSE), and measures that assessed for positive psychologic phenomena (e.g., resilience) were often lacking. Therefore, researchers likely developed composite definitions of successful aging post hoc and based them on the absence of impaired functioning. The prominence of these kinds of definitions may arise from lower perceived clinical need to identify and attain consensus about a phenotype of successful aging as opposed to frailty in old age (35).

Despite the differences among these definitions, there were several common findings across the literature. The mean proportion of successful agers was 35.8% (SD: 19.8), which suggests that a sizable minority of older adults was characterized as successfully aging. Disability and physical functioning, in particular ADL performance, appeared in nearly every definition, which likely arises in part from the popularity of the Rowe and Kahn (12) model of successful aging. The prominence of disability contrasts with findings from qualitative studies in which older adults were asked to either rate the essential components of successful aging (15, 36) or respond to open-ended queries about the definition of successful aging (37, 38). Older adults more commonly endorse social engagement and positive outlook toward life rather than physical health status.

Several variables emerged as consistent predictors of successful aging. The most consistent predictor was being “young-old.” Furthermore, studies with older minimum ages of their samples reported lower proportion of successful agers. Given the centrality of disability/physical functioning to these definitions, it is not surprising that the proportion of successful agers declines with age (39). Other variables found in four or more studies and significantly related to successful aging in 75% or more of those studies reporting associations were health-related variables: absence of hearing problems, arthritis, and disability. In addition, not currently smoking related strongly to successful aging, supporting the belief that it is never too late to quit smoking (40). Moderately strong relationships (significant in 50%-75% of studies) included better self-rated health, further confirming the validity of elderly people's appraisal of their health as a predictor of outcome (41). Global cognitive functioning was related to successful aging, yet more fine-grained neuropsychologic measures were reported in too few studies to measure their consistency (42, 43). It will be important to ascertain which neuropsychologic domains are most related to successful aging (44). Moderate support was also found for greater physical exercise, lower systolic blood pressure, fewer medical conditions, and less severe or absence of depression. Although these identified relationships make intuitive sense, it is encouraging that potentially modifiable predictors (e.g., smoking, exercise, and depression) had bearing on whether individuals were classified as successful agers. Further encouraging was that these relationships were identified as predictors of long-term successful aging as well as concurrently. Thus, the proportion of individuals successfully aging (as defined in these studies) could be theoretically altered behaviorally, although the effectiveness of health-promotion programs so far has been limited (45).

Interestingly, demographic variables, including current marital status, female gender, and ethnicity, typically did not relate to successful aging. Investigators have reported a relationship between each of these variables and mortality (46, 47) as well as rates of disease and disability (48). In addition, income and education were not consistently related to successful aging, each of which is a resource that predicts positive health status in longitudinal studies of older adults (48). One potential reason for the lack of association with these variables and successful aging may be sampling bias; that is, older adults with lower educational and economic resources may be less likely to participate in these studies. Another more intriguing possibility may be that when composite outcomes are used (i.e., successful aging definitions), the effect of demographic and socioeconomic indicators is lessened compared with individual variables. Coupled with the observation that some variables did correlate with composite definitions suggests that researchers should investigate the differences in strength of association between individual and composite outcomes within the same study sample.

The results of this review suggest several directions for future research on successful aging:

1) The disconnect between these operational definitions, lifespan developmental theories, and older adults' definitions of successful aging indicates the need to expand these primarily biomedical definitions in the larger studies to more “biopsychosocial” definitions (49). The incorporation of lifespan developmental theories to large-scale studies of successful aging such as the selection, optimization, and compensation model (13) has been limited. Efforts to integrate developmental theories (e.g., measuring perceptions of change in social relationships), findings from qualitative research with older people (e.g., measuring optimism or well-being), and psychosocial factors identified in samples of centenarians may broaden the scope of successful aging research toward a more biopsychosocial approach.

2) The ideal definition of successful aging should be acceptable to clinicians, researchers, and older adults alike yet is likely dependent on the research question. A majority of the papers defined successful agers as older adults whose health status was similar to that of younger people or functionally ideal aging (“escapers” of physical illnesses and disability (50)). Another possible phenotype, likely representing a larger number of elderly people, is that of people who experience disability/chronic illness but maintain cognitive functioning, life satisfaction, and social engagement (e.g., “survivors” of physical illness and disability (50)). Understanding adaptive processes by which older adults preserve well-being amid physical functional losses would inform preventative interventions. Thus, determining the phenotypic characteristics of both survivors and escapers is important.

3) With regard to operationalizing successful aging, studies should report proportion meeting criteria and associations with components of successful aging as well as composite definitions, because the domains are more often agreed on than any particular combination. Researchers should note that the greater the number of domains included, the more restrictive the definition of successful aging. Each subsequent domain should increase the predictive validity of the composite definition. An alternative may be to use flexible definitions such as requiring three of five dimensions, similar to that proposed for frailty (35).

4) Some predictors of successful aging have received little attention but could greatly advance this field. Examining the effect of genetic markers such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (e.g., APOE alleles) (51) or telomere length (52), in relation to successful and unsuccessful groups could be highly fruitful, paralleling genetic research on exceptional longevity (53). There are also emerging methods for measuring cumulative risk such as allostatic load (54) that may predict substantial variance in successful aging. Understanding “access” to successful aging will also be important such as opportunities for health care (55) and good nutrition (56). Finally, there are sociologic and psychologic variables that have received less study but are identified by older adults as integral to successful aging (37, 38); among them are positive spirituality (57) and resilience (58).

In summary, there have been multiple ways in which successful aging has been operationally defined, measured, and predicted with some consistent and some variable results. Nevertheless, this literature has paved the way for future studies of successful aging. Prevention of disability and cognitive decline are of paramount interest for successful aging, and studies in this review offer evidence that health-related practices (e.g., smoking, exercise), chronic illnesses (e.g., diabetes, arthritis), and subjective health are more robust determinants of successful aging than are demographic or socioeconomic factors. Critical next steps are to attain consensus on the phenotype(s) of successful aging and to expand the scope of predictors studied to enable basic science to examine its biologic substrates and for public health initiatives to address the factors that encourage healthy aging.

1 Lupien SJ, Wan N: Successful ageing: from cell to self. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2004; 359: 1413– 1426.Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Peel NM, McClure RJ, Bartlett HP: Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. Am J Prev Med 2005; 28: 298– 304.Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Bowling A: The concepts of successful and positive ageing. Fam Pract 1993; 10: 449– 453.Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Phelan EA, Larson EB: “Successful aging'—where next? J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 1306– 1308.Google Scholar

5 Kahn RL: On “successful aging and well-being: self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn.' Gerontologist 2002; 42: 725– 726.Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Rowe JW, Kahn RL: Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997; 37: 433– 440.Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Fries JF: Successful aging—an emerging paradigm of gerontology. Clin Geriatr Med 2002; 18: 371– 382.Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Jeste DV: Feeling fine at a hundred and three secrets of successful aging. Am J Prev Med 2005; 28: 323– 324.Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Active Ageing a Policy Framework. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003Google Scholar

10 White House Commission on Aging: The Road to an Aging Policy for the 21st Century. Services UDoHaH, 1996Google Scholar

11 Action Plan for Aging Research. Aging NIo U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar

12 Rowe JW, Kahn RL: Human aging: usual and successful. Science 1987; 237: 143– 149Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Baltes PB: On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny. Am Psychol 1997; 52: 366– 380Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Schulz R, Heckhausen J: A life span model of successful aging. Am Psychol 1996; 51: 702– 714Crossref, Google Scholar

15 von Faber M, Bootsma-van der Wiel A, van Exel E, et al: Successful aging in the oldest old: who can be characterized as successfully aged? Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 2694– 2700Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Cohen RD: Successful aging and well-being: self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist 2002; 42: 727– 733Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Riley MW: Successful aging. Gerontologist 1998; 38: 151Google Scholar

18 Butler RN: What is “successful' aging? Geriatrics 1988; 43: 11, 15Google Scholar

19 Vaillant GE, Mukamal K: Successful aging. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 839– 847Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Bearon LB: Successful aging: what does the ‘good life’ look like? The Forum for Family & Consumer Issues 1996; 1: 1– 6Google Scholar

21 Peel NM, Bartlett RJ, McClure HB: Healthy ageing: how is it defined and measured? Aust J Ageing 2004; 23: 115– 119Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Bland JM, Altman DG: Statistics notes: the odds ratio. BMJ 2000; 320: 1468Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Jorm AF, Christiansen H, Henderson S, et al: Factors associated with successful ageing. Aust J Ageing 1998; 17: 33– 37.Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Newman AB, Arnold AM, Naydeck BL, et al: “Successful aging': effect of subclinical cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 2315– 2322.Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Roos NP, Havens B: Predictors of successful aging: a twelve-year study of Manitoba elderly. Am J Public Health 1991; 81: 63– 68Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, et al: Successful aging: predictors and associated activities. Am J Epidemiol 1996; 144: 135– 141.Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Leveille S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al: Aging successfully until death in old age: opportunities for increasing active life expectancy. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 149: 654– 664.Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Hogan DB, Fung TS, Ebly EM: Health, function, and survival of a cohort of very old Canadians: results from the second weave of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique 1999; 90: 338– 342.Google Scholar

29 Grundy E, Bowling A: Enhancing the quality of extended life years. Identification of the oldest old with a very good and very poor quality of life. Aging Ment Health 1999; 3: 199– 212.Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Lamb V, Myers G: A comparative study of successful aging in three Asian countries. Population Research and Policy Review 1999; 18: 433– 449.Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Menec VH: The relation between everyday activities and successful aging: a 6-year longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2003; 58: S74– 82.Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Burke GL, Arnold AM, Bild DE, et al: Factors associated with healthy aging: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 254– 262.Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Garfein AJ, Herzog A: Robust aging among the young-old, old-old, and oldest-old. J Gerontol 1995; 50B: S77– S87.Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Montross LP, Depp CA, Reichstadt J, et al: Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14: 43– 51.Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al: Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol 2001; 56A: M146– M156.Google Scholar

36 Knight T, Ricciardelli LA: Successful aging: perceptions of adults aged between 70 and 101 years. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2003; 56: 223– 245.Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Phelan EA, Anderson LA, LaCroix AZ, et al: Older adults' views of 'successful aging'—how do they compare with researchers' definitions? J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52: 211– 216Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Tate RB, Lah L, Cuddy TE: Definition of successful aging by elderly Canadian males: the Manitoba Follow-up Study. Gerontologist 2003; 43: 735– 744Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Freedman V, Aykan H, Martin L: Another look at aggregate changes in severe cognitive impairment: further investigation into the cumulative effects of three survey design issues. J Gerontol 2002; 57: 126– 131.Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Andrews GJ, Clark M, Luszcz M: Successful aging in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Aging: applying the MacArthur model crossnationally. J Soc Issues 2002; 58: 749– 765.Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Schoenfeld DE, Malmrose LC, Blazer DG, et al: Self-rated health and mortality in the high-functioning elderly—a closer look at healthy individuals: MacArthur field study of successful aging. J Gerontol 1994; 49: M109– 115.Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Berkman LF, Seeman TE, Albert M, et al: High, usual and impaired functioning in community-dwelling older men and women: findings from the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Aging. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46: 1129– 1140.Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Andrews GJ, Clark M, Luszcz M: Successful aging in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Aging: applying the MacArthur model crossnationally. J Soc Issues 2002; 4: 749– 765.Google Scholar

44 Fillit H, Butler R, O'Connell A, et al: Acheiving and maintaining cognitive vitality with aging. Mayo Clin Proc 2002; 77: 681– 696.Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Syme SL: Psychosocial interventions to improve successful aging. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 400– 402.Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Bassuk SS, Berkman LF, Amick BC: Socioeconomic status and mortality among the elderly: findings from four U.S. communities. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155: 520– 533.Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Gardner J, Oswald A: How is mortality affected by money, marriage, and stress? J Health Econ 2004; 23 1181– 1207Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Adler NE, Boyce WT, Chesney MA, et al: Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am J Psychol 1994; 49: 15– 24.Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Inui TS: The need for an integrated biopsychosocial approach to research on successful aging. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 391– 394.Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Evert J, Lawler E, Bogan H, et al: Morbidity profiles of centenarians: survivors, delayers, and escapers. J Gerontol 2001; 58: 232– 237.Google Scholar

51 Small BJ, Rosnick CB, Fratiglioni L, et al: Apolipoprotein E and cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging 2004; 19: 592– 600.Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, et al: Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101: 17312– 17315.Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Perls T, Terry D: Genetics of exceptional longevity. Exp Gerontol 2003; 38: 725– 730.Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Karlamangla AS, Singer BH, McEwen BS, et al: Allostatic load as a predictor of functional decline. MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Clin Epidemiol 2002; 55: 696– 710.Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Kane RL: The contribution of geriatric health services research to successful aging. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 460– 462.Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Miller SM: Successful aging in America, part I. Nutrition, the elderly, and the laboratory. MLO Med Lab Obs 1997; 29: 22– 25, 28–30; quiz 32–33.Google Scholar

57 Crowther MR, Parker MW, Achenbaum WA, et al: Rowe and Kahn's model of successful aging revisited: positive spirituality— the forgotten factor. Gerontologist 2002; 42: 613– 620.Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Wilcox S, Evenson K, Aragaki A, et al: The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: the Women's Health Initiative. Health Psychol 2003; 22: 513– 522.Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Palmore E: Predictors of successful aging. Gerontologist 1979; 19: 427– 431.Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Ford AB, Haug MR, Stange KC, et al: Sustained personal autonomy: a measure of successful aging. J Aging Health 2000; 12: 470– 489.Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Hubert HB, Bloch DA, Fries JF: Risk factors for physical disability in an aging cohort: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study. J Rheumatol 1993; 20: 480– 488.Google Scholar

62 Avlund K, Holstein BE, Mortensen EL, et al: Active life in old age. Combining measures of functional ability and social participation. Dan Med Bull 1999; 46: 345– 349.Google Scholar

63 Uotinen V, Suutama T, Ruoppila I: Age identification in the framework of successful aging. A study of older Finnish people. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2003; 56: 173– 195.Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Baltes MM, Lang FR: Everyday functioning and successful aging: the impact of resources. Psychol Aging 1997; 12: 433– 443.Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Reed D, Foley D, White L, et al: Predictors of healthy aging in men with high life expectancies. Am J Public Health 1998; 88: 1463– 1468.Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Michael YL, Graham AC, Coakley E, et al: Health behaviors, social networks, and healthy aging: cross-sectional evidence from the Nurses Health Study. Quality of Life Research 1999; 8: 711– 722.Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Almeida OP, Norman P, Hankey G, et al: Successful mental health aging: results from a longitudinal study of older Australian men. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14: 27– 35.Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Day AT, Day LH: Living arrangements and “successful' ageing among ever-married American white women 77–87 years of age. Aging and Society 1993; 13: 365– 387.Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Liang J, Shaw BA, Krause NM, et al: Changes in functional status among older adults in Japan: successful and usual aging. Psychol Aging 2003; 18: 684– 695.Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Guralnik JM, Kaplan GA: Predictors of healthy aging: prospective evidence from the Alameda County study. Am J Public Health 1989; 79: 703– 708Crossref, Google Scholar