Psychotherapy Plus Antidepressant for Panic Disorder With or Without Agoraphobia: Systematic Review

Abstract

Background:

Panic disorder can be treated with psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy or a combination of both. Aims: To summarise the evidence concerning the short- and long-term benefits and adverse effects of a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant treatment. Method: Meta-analyses and meta-regressions were undertaken using data from all relevant randomised controlled trials identified by a comprehensive literature search. The primary outcome was relative risk (RR) of response. Results: We identified 23 randomised comparisons (21 trials involving a total of 1709 patients). In the acute-phase treatment, the combined therapy was superior to antidepressant pharmacotherapy (RR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.02–1.52) or psychotherapy (RR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.30). After termination of the acute-phase treatment, the combined therapy was more effective than pharmacotherapy alone (RR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.23–2.11) and was as effective as psychotherapy (RR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.79–1.16). Conclusions: Either combined therapy or psychotherapy alone may be chosen as first-line treatment for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, depending on the patient's preferences.

(Reprinted with permission from British Journal of Psychiatry 2006; 188:305–312)

Two categories of treatment have been shown to be effective in treating panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. One is psychotherapy and the other is pharmacotherapy using antidepressants and benzodiazepines (American Psychiatric Association, 1998; Nathan & Gorman, 2002). However, it is uncertain whether combining these two forms of treatment confers any additional benefit over and above either treatment alone, both in the short term and in the long term. The primary objective of this systematic review was therefore to review and synthesise evidence from randomised controlled trials that examined the short- and long-term benefits and adverse effects of a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressants compared with either therapy alone for the treatment of panic disorder. A separate review that focuses on the use of psychotherapy in combination with benzodiazepines is in preparation.

METHOD

INCLUSION CRITERIA

Randomised controlled trials that compared a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant pharmacotherapy with either treatment alone for adult patients with panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, were eligible for inclusion.

We included both individual and group formats of behaviour therapy involving some kind of exposure, cognitive therapy involving some kind of cognitive restructuring, cognitive-behavioural therapy involving elements of both cognitive and behavioural therapy, and other psychological approaches. All commonly prescribed antidepressants were eligible, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Studies in which there was irregular use of benzodiazepines or in which benzodiazepines were regularly administered at a constant dosage for long-term users were included, because it was considered that these did not undermine the comparability of the combined therapy with either monotherapy, and because such practices would reflect clinical reality more closely. The effect of this decision was examined in a sensitivity analysis. Studies in which benzodiazepines were combined with antidepressants as part of the study medication were excluded.

IDENTIFICATION OF TRIALS

We searched the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register (CCDANCTR) with the keywords ANTIDEPRESSANT and PANIC up to April 2003. The CCDANCTR is a study-based register of randomised trials that incorporates the results of group searches of Medline (from 1966), EMBASE (from 1980), CINAHL (from 1982), PsycINFO (from 1974), PSYNDEX (from 1977) and LILACS (from 1982 to 1999), and hand searches of major psychiatric and medical journals, conference proceedings and trial registers. Two additional searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Medline were also undertaken. No language restrictions were imposed on the search.

Two reviewers examined the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the electronic search, and then checked the full articles for eligibility. To identify further trials, the references cited in these studies and in other review papers were also checked, relevant studies were subjected to SciSearch, and experts in the field were contacted.

QUALITY ASSESSMENT AND DATA EXTRACTION

Two independent reviewers assessed the methodological quality of the selected studies according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2, 2 (Alderson et al., 2004), which emphasises allocation concealment (A, low risk of bias; B, moderate risk of bias; C, high risk of bias). We also rated the study as ‘blinded’ when at least one outcome measure was assessed by an independent assessor who was masked to treatment allocation, and ‘unblinded’ when the outcomes were assessed by someone who was aware of the allocated treatment.

In addition, we rated the adequacy of the psychotherapy as ‘good’ when the way in which psychotherapy was actually conducted was examined by a third reviewer by means of audiotapes, etc., and as ‘poor’ when the authors only provided a description of the therapy procedure.

Two reviewers independently extracted data from the original reports using standardised data-extraction forms. Our primary outcome was ‘response’—that is, substantial improvement from baseline, such as ‘very much or much improved’ according to the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI; Guy, 1976), a decrease of more than 40% in the Panic Disorder Severity Scale score (Shear et al., 1997), and a reduction of more than 50% in panic frequency or the Fear Questionnaire—Agoraphobia sub-scale (Marks & Mathews, 1979). Our secondary outcomes included global severity, frequency of panic attacks, phobic avoidance, general anxiety, depression, social dysfunction, patient satisfaction and cost-effectiveness. The total number of drop-outs for any reason was regarded as a proxy measure of the acceptability of treatment. Adverse effects were evaluated by examining the number of drop-outs due to adverse effects.

Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus between two or, where necessary, between all three reviewers. The decision to include in the meta-analysis studies that did not appropriately conceal allocation, that were ‘unblinded’ or that scored ‘poor’ with regard to adequacy of psychotherapy was examined in sensitivity analyses.

DATA SYNTHESIS

Data were entered into Review Manager 4.2 (Windows software provided by the Cochrane Collaboration and available at http://www.cc-ims.net/RevMan) and double-checked for accuracy. For dichotomous outcomes, relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a random-effects model, which yields superior results in terms of clinical interpretability and external generalisability compared with fixed-effects models and odds ratios or risk differences (Furukawa et al., 2002). For continuous outcomes, the standardised weighted mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a random-effects model.

For dichotomous outcomes, we used intention-to-treat analyses according to the following principle. When data on drop-outs were carried forward and included in the efficacy evaluation using the last-observation-carried-forward method, they were included as such. When drop-outs were excluded from any assessment in the primary studies (e.g. those who never returned for assessment after randomisation), they were considered to be non-responders in both active and comparison groups. The same principles were applied to outcomes after the end of continuation treatment.

SUBGROUP AND SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

To investigate clinical heterogeneity, we planned three a priori subgroup analyses: for types of psychotherapies; for classes of antidepressants; and for patients with or without agoraphobia. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was assessed with the I-squared statistic and the Q statistic. If significant heterogeneity was noted (I2 > 30% or P < 0.10) (Higgins et al., 2003), sources were investigated.

In addition, sensitivity analyses were performed, restricting the data syntheses to studies of higher quality in terms of allocation concealment, blinding, operational diagnosis, adequacy of psychotherapy and control of benzodiazepine co-intervention. Meta-regressions (Thompson & Sharp, 1999) were also performed to determine whether these variables had a significant effect on the pooled effect sizes.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTION OF STUDIES

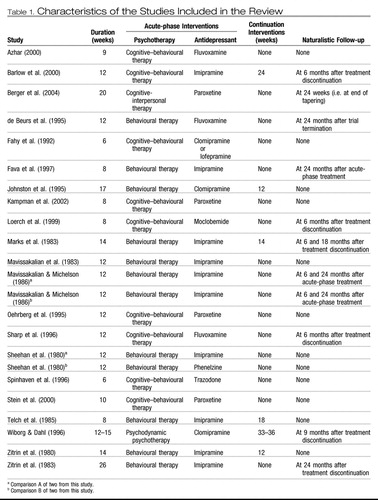

The electronic search identified 139 studies from CCDANCTR, an additional 164 studies from CENTRAL and 35 studies from Medline. By browsing their titles and abstracts, the two independent reviewers identified 135 articles as possible candidates, and full copies of these articles were obtained. Two independent reviewers then examined the strict eligibility of these papers. As a result of a further reference search, SciSearch and personal contacts, we identified 21 studies which satisfied the strict eligibility criteria. The interrater reliability of the eligibility criteria was found to be 94%. Because two trials provided two comparisons each (Sheehan et al., 1980; Mavissakalian & Michelson, 1986), there were 23 randomised comparisons involving a total of 1709 participants (Table 1) (a more detailed version of Table 1 is presented as a data supplement to the online version of this paper).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Review

The majority of the participants were women, and their average age was between 30 and 40 years. They had suffered from panic disorder for 5 to 10 years. Only one comparison focused on patients with panic disorder without agoraphobia, whereas 13 comparisons focused on patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia. The other studies were of mixed populations.

The typical length of the acute-phase active treatment was between 8 and 12 weeks. In total, 12 studies administered behaviour therapy that consisted of exposure and/or breathing retraining and/or relaxation exercises. None of the studies used narrowly defined cognitive therapy that relied only on cognitive restructuring. Nine studies administered cognitive–behavioural therapy that consisted of both behaviour and cognitive therapy elements. Two studies were categorised as ‘Other psychotherapies’. One of these used a mixture of cognitive–behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy (Berger et al., 2004) and the other used brief psychodynamic psychotherapy (Wiborg & Dahl, 1996). With regard to medications that were administered, 14 studies used TCAs (with an average dose of 146 mg/day of imipramine equivalents), 7 studies used SSRIs (average dose 32 mg/day fluoxetine equivalents) and 2 studies used monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

Response was defined in terms of the CGI scale in eight studies, in terms of the Fear Questionnaire Agoraphobia sub-scale in three studies, in terms of panic frequency in two studies, and in terms of other measures in 10 studies. In total, 13 studies reported continuous outcomes of global severity, 15 reported on panic frequency, 20 reported on agoraphobia, 18 reported on general anxiety, 18 reported on depression and 13 reported on social dysfunction. None of the studies reported on patient satisfaction or cost issues.

Six studies reported the results at the end of continuation treatment which lasted for between 3 and 9 months. Nine studies followed up the patients 6–24 months after termination of acute-phase and continuation treatments.

With regard to validity, all but four comparisons from three trials (Mavissakalian & Michelson, 1986; Wiborg & Dahl, 1996; Berger et al., 2004) scored B for allocation concealment. In total, 19 studies conducted blinded outcome assessments and four studies were unblinded (Mavissakalian et al., 1983; Spinhoven et al., 1996; Azhar, 2000; Berger et al., 2004). The interrater reliability of these two validity criteria was 94% for allocation concealment and 83% for outcome assessment.

Six studies reported that quality control of the psychotherapy was adequate (Zitrin et al., 1983; de Beurs et al., 1995; Fava et al., 1997; Loerch et al., 1999; Barlow et al., 2000; Kampman et al., 2002). Four studies acknowledged financial support from pharmaceutical companies (Fahy et al., 1992; de Beurs et al., 1995; Sharp et al., 1996; Loerch et al., 1999), and these companies marketed the drugs involved in the trials. Oehrberg et al. (1995) did not acknowledge financial support from a drug company, but three of the co-authors of that study were company employees.

PSYCHOTHERAPY PLUS ANTIDEPRESSANT V. ANTIDEPRESSANT TREATMENT

ACUTE-PHASE TREATMENT

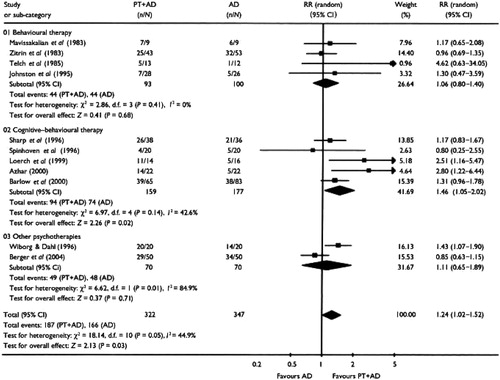

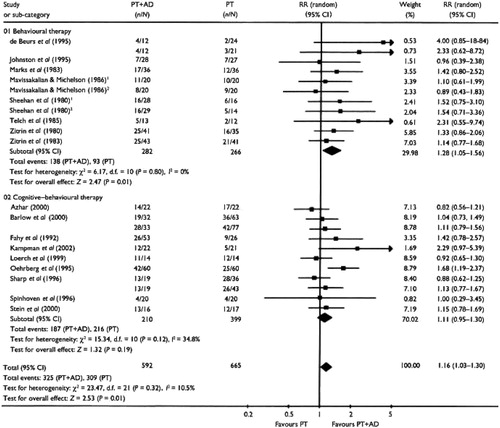

Combining data from 11 studies involving 322 patients in the psychotherapy plus antidepressant arm and 347 patients in the antidepressant arm showed that the combination was 1.24 times (95% CI 1.02–1.52) more likely to produce a response at the end of 2–4 months of acute-phase treatment compared with the antidepressant alone (Fig. 1).There was moderate but statistically significant heterogeneity (P = 0.05, I2 = 44.9%). Furthermore, the funnel plot indicated that there was some publication bias, with one small study reporting an extreme result (Telch et al., 1985). Subgroup analyses suggested that there was greater heterogeneity in the ‘other psychotherapies’ category (Wiborg & Dahl, 1996; Berge et al., 2004). When we omitted these studies, limiting the included studies to those that employed behavioural or cognitive-behavioural therapies, the RR remained the same (RR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.08–1.52) and there was no longer statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.18, I2 = 30.5%) or funnel-plot asymmetry.

Figure 1. Psychotherapy Plus Antidepressant v. Antidepressant Alone: Response at the End of Acute-phase Treatment. PT, Psychotherapy; AD, Antidepressant; RR, Relative Risk

The superiority of the combination therapy was corroborated by secondary analyses using continuous data. The combination treatment decreased the global severity of the disorder (SMD = −0.36, 95% CI −0.60 to −0.11), depression (SMD = −0.52, 95% CI −0.76 to −0.28) and social dysfunction (SMD = −0.47, 95% CI −0.89 to −0.05).

There were no differences in overall drop-outs or in drop-outs due to side-effects.

CONTINUATION TREATMENT

There was considerable statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.005, I2 = 76.8%). Limiting the studies to behaviour and cognitive-behavioural therapies removed this heterogeneity (P = 0.55, I2 = 0%) and suggested that the combination therapy was 1.63 (95% CI 1.21–2.19) times more likely to produce a response than antidepressant treatment alone.

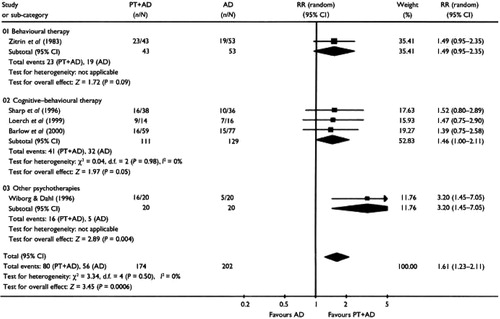

AFTER TERMINATION OF TREATMENT

Figure 2 shows the findings of five studies that reported outcomes after 6–24 months of naturalistic follow-up. Combining outcomes based on 376 participants, the combination therapy was still superior to antidepressant treatment alone (RR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.23–2.11). No heterogeneity was noted (P = 0.50, I2 = 0%).

Figure 2. Psychotherapy Plus Antidepressant v. Antidepressant Alone: Response After Termination of Treatment. PT, Psychotherapy; AD, Antidepressant; RR, Relative Risk

PSYCHOTHERAPY PLUS ANTIDEPRESSANT V. PSYCHOTHERAPY

Although the comparison of psychotherapy plus antidepressant with psychotherapy alone is theoretically different from the comparison of psychotherapy plus antidepressant with psychotherapy plus placebo (Hollon & DeRubeis, 1981), our meta-analytical summaries were remarkably similar for the acute phase and follow-up evaluations. We therefore report here the aggregated results of trials comparing psychotherapy plus antidepressant with psychotherapy alone and psychotherapy plus placebo.

ACUTE-PHASE TREATMENT

Combining data from 19 comparisons involving 592 patients in the psychotherapy plus antidepressant arm and 665 patients in the psychotherapy arm demonstrated that the combination was 1.16 times (95% CI 1.03–1.30) more likely to produce a response at the end of acute-phase treatment than psychotherapy alone (Fig. 3).The test for heterogeneity was not significant.

Figure 3. Psychotherapy Plus Antidepressant v. Psychotherapy Alone: Response at the End of Acute-phase Treatment. PT, Psychotherapy; AD, Antidepressant; RR, Relative Risk, I. Comparison A of Two From this Study;2. Comparison B of Two From This Study

The same superiority of the combined therapy was noted with regard to the global severity (SMD = −0.43, 95% CI −0.60 to −0.26). When different aspects of panic disorder were examined, the combination therapy was found to be significantly superior with regard to reduction in phobic avoidance (SMD = −0.31, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.12), general anxiety (SMD = −0.41, 95% CI −0.59 to −0.23), depression (SMD = −0.39, 95% CI −0.59 to −0.20) and social dysfunction (SMD = −0.36, 95% CI −0.61 to −0.11).

Although the two arms did not differ in terms of overall drop-out rates, drop-outs due to side-effects were much more frequent in the combined therapy arm (RR = 3.01, 95% CI 1.61–5.63).

CONTINUATION TREATMENT

For as long as the treatments were continued, the advantage of the combination therapy appeared to persist, as the response rate at the end of continuation treatment still favoured the combination therapy (RR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.00–1.51), and the global severity was significantly lower in the combination arm (SMD = −0.65, 95% CI −0.97 to −0.33).

AFTER TERMINATION OF TREATMENT

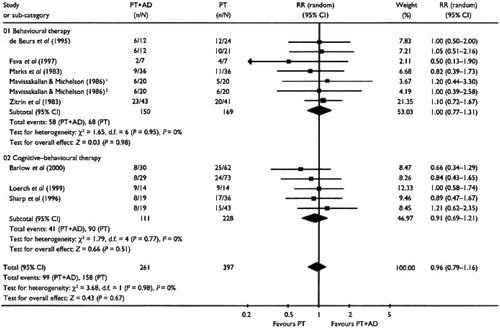

In total, 658 patients from nine studies were assessed 6 to 24 months after discontinuing treatment (Fig. 4).Neither the response rate nor the global severity measure differed significantly between the two arms, which suggests that any advantage of the combination therapy disappeared over time.

Figure 4. Psychotherapy Plus Antidepressant v. Psychotherapy Alone: Response After Termination of Treatment. PT, Psychotherapy; AD, Antidepressant; RR, Relative Risk. I, Comparison A of Two From This Study; 2. Comparison B of Two From This Study

SUBGROUP AND SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

TYPES OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

For all the outcomes during the acute-phase or continuation treatments or after termination of treatment, the confidence intervals of the pooled estimates of the effectiveness of behaviour therapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy overlapped to a significant degree (Figs 1–4). Pooling these two types of psychotherapy together seldom resulted in significant heterogeneity. The only exception was the ‘other psychotherapies’ category for the comparison of psychotherapy plus antidepressant with antidepressant treatment alone. The results of these studies were sometimes directionally different from those of the other studies in which behavioural or cognitive-behavioural therapies were administered, and combining them often resulted in significant heterogeneity.

CLASSES OF ANTIDEPRESSANTS

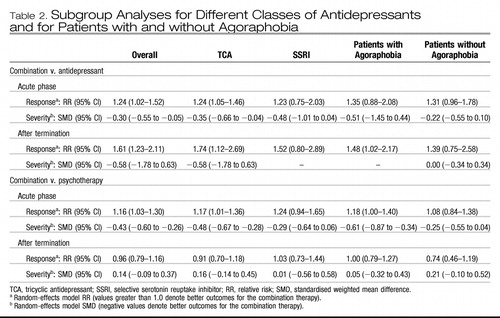

We performed a meta-analysis of 14 studies in which TCAs were used and 7 studies in which SSRIs were used. The pooled estimates of the effect size of these two meta-analyses were very similar both to each other and to the overall results in terms of response or global severity (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Subgroup Analyses for Different Classes of Antidepressants and for Patients with and without Agoraphobia

PATIENTS WITH AND WITHOUT AGORAPHOBIA

We performed a meta-analysis of 13 studies that focused on patients with agoraphobia only. The results were very similar to the overall results, and overlapped substantially with the results of the only study that focused on patients without agoraphobia (Barlow et al., 2000) (Table 2).

When only those studies that were of higher quality in terms of allocation concealment, blinding, diagnostic accuracy, adequacy of psychotherapy or control of benzodiazepine co-intervention were included, the pooled estimates that were obtained were virtually identical to the overall results. Meta-regression analysis did not reveal any significant contribution of these quality variables, either individually or in combination, which suggests that the overall findings are robust.

DISCUSSION

IMPORTANCE OF THE CLINICAL PROBLEM IN THE CONTEXT OF PREVIOUS REVIEWS

There are a number of reasons why the clinical question concerning combined psychotherapy and antidepressant treatment is important. First, combination therapy is frequently provided in clinical practice, possibly because 30–50% of patients remain unimproved at the end of acute-phase treatment by either monotherapy. Second, it is now increasingly recognised that pharmacotherapy alone tends to result in substantial relapse rates not only when discontinued (Mavissakalian & Perel, 2002), but even when maintained at adequate dosage (Simon et al., 2002), whereas psychotherapy is associated with fewer relapses in the short term, but may not always be able to prevent them in the long term (Fava et al., 2001).

Several reviews of combination therapy can be found in the literature, but their conclusions have been variable, with some favouring the combination (Mattick et al., 1990; van Balkom et al., 1997), some favouring monotherapy (Gould et al., 1995; Taylor, 2000) and others drawing mixed or cautious conclusions (American Psychiatric Association, 1998; Schmidt et al., 2001). Most of these reviews have been either unsystematic or narrative only (American Psychiatric Association, 1998; Taylor, 2000; Schmidt et al., 2001) and, where meta-analytical summary was undertaken, this did not focus on head-to-head comparisons (Mattick et al., 1990; Gould et al., 1995; van Balkom et al., 1997), a practice that is known to be misleading (Song et al., 2003).

CURRENT FINDINGS

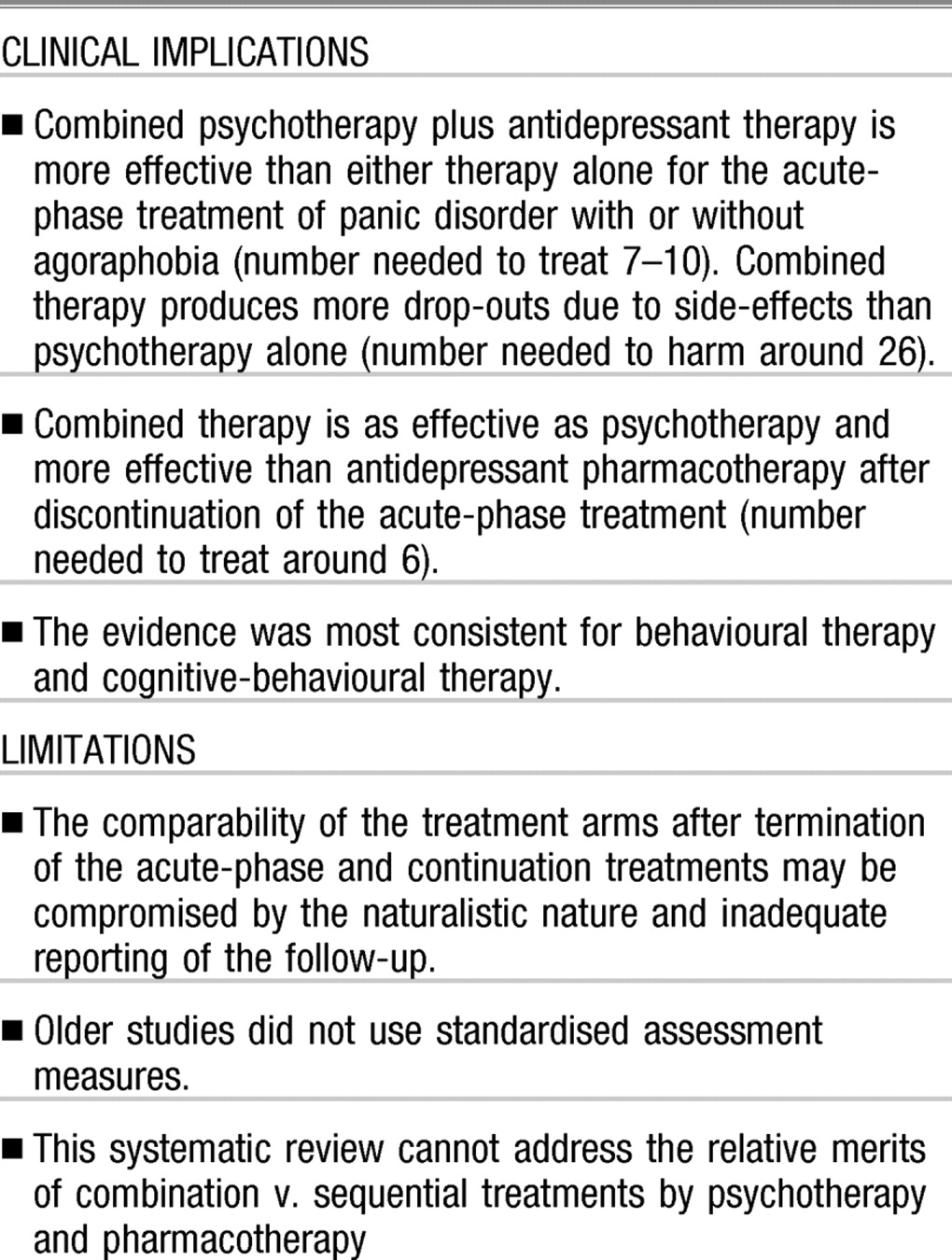

This systematic review demonstrated that combining psychotherapy and antidepressant treatment produced outcomes that were consistently superior to either treatment alone for the acute-phase treatment, in terms of both the response rates and the continuous outcomes measuring various aspects of the disorder. Taking the average response rates of 50–70% for single-modality treatments, the pooled RR of 1.2 for the combination therapy is equivalent to a value for the number needed to treat of between 7 and 10. During the acute-phase treatment, combination therapy resulted in more drop-outs due to side-effects than psychotherapy alone, and the number needed to harm was around 26.

The naturalistic follow-up of the randomised controlled trials that were included suggested that the combination therapy had a sustained advantage over antidepressant therapy. At 6–24 months after termination of treatment, the combined therapy still showed a number needed to treat of around 6 compared with antidepressant treatment alone. With regard to the comparison between the combination therapy and psychotherapy, there was no evidence of long-term benefit of the former compared with the latter. In this respect, it is interesting to note that, despite recent admonitions from several experts (Taylor, 2000; Schmidt et al., 2001; Foa et al., 2002), the combination therapy was found to have no disadvantage in the long term.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This systematic review has several major strengths. First, we performed systematic and comprehensive searches for relevant trials. We identified 23 randomised comparisons from 21 studies, whereas previous reviews included a maximum of 13 studies. Second, we applied the intention-to-treat principle when performing meta-analysis of dichotomous outcomes by counting all of the drop-outs as non-responders. This policy is especially pertinent in the context of the relative merits of the combination therapy over monotherapy in the long term, because we are interested in the number of patients doing well as a proportion of all those who started the acute-phase therapy, not just those who successfully completed it. Finally, the a priori planned heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses indicated that the results of the analyses were quite robust.

However, several potential limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, the comparability of the treatment arms after termination of acute-phase and continuation treatments may be compromised by the naturalistic nature of the follow-up. Participants were usually free to seek further treatment between the termination of treatment and the follow-up assessments, and 30–77% of them received additional therapies. Unfortunately, inadequate reporting of additional therapies precluded further examination of this issue across studies. If the published studies had reported the number of patients who did well without further treatment, the interpretation of the relative merits of the combination therapy v. monotherapies would have been more straightforward. Second, funnel-plot analyses suggested the possibility of publication bias. However, the exclusion of outliers did not affect the pooled estimates. Third, we must point out that until recently there have been no widely accepted and validated rating scales for panic disorder, and that some of the studies that were included used the authors' original scales. One study indicated that rating scales which have not been validated or standardised are more likely to report statistically significant findings (Marshall et al., 2000). Fourth, owing to this lack of accepted assessment methods for panic disorder, the definition of response (our primary outcome) had to be operationalised by a variety of measures. However, these overall results were corroborated by analyses that focused on specific aspects of the symptoms of panic disorder.

It must be noted that our review does not address the relative merits of combination therapy compared with sequential treatments. Given the present findings, some might argue for psychotherapy alone as first-line treatment, only considering combination therapy if psychotherapy fails. Although this appears to be a viable option, such a practice cannot be informed by the data available from these trials.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The current findings from the best available evidence suggest that either combined therapy or psychotherapy alone may be chosen as first-line treatment for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. Treatment decisions may depend on the patient's preferences and values. Antidepressant pharmacotherapy alone is not to be recommended as first-line treatment where appropriate resources are available. Although none of the studies included in this review examined cost issues, economic consideration of the costs of years of medication compared with ‘one-off’ psychological treatment would also favour the use of psychotherapy (Otto et al., 2000).

Several issues warrant further investigation. First, in the acute-phase treatment, if we adhere to the strict intention-to-treat principle, the response rates are only slightly above 50% for combination therapy and slightly below 50% for psychotherapy alone. Therefore additional strategies may be required to deal with partial and non-responders to these therapies. Second, there are currently only limited data available on the effects of combining antidepressants with non-cognitive-behavioural therapies, such as psychodynamic and interpersonal therapies. In this review, the only available trial that involved psychodynamic therapy showed increased benefit when combined with antidepressants. This suggests the potential value of future trials designed to investigate this type of combination in the treatment of panic disorder.

Alderson, P., Green, S. & Higgins, J. P. T. (eds) (2004) Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.2. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association (1998) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 1– 34.Crossref, Google Scholar

Azhar, M. Z. (2000) Comparison of fluvoxamine alone, fluvoxamine and cognitive psychotherapy and psychotherapy alone in the treatment of panic disorder in Kelantan - implications for management by family doctors. Medical Journal of Malaysia, 55, 402– 408.Google Scholar

Barlow, D. H., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., et al (2000) Cognitive–behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283, 2529– 2536.Crossref, Google Scholar

Berger, P., Sachs, G., Amering, M., et al (2004) Personality disorder and social anxiety predict delayed response in drug and behavioral treatment of panic disorder, Journal of Affective Disorders, 80, 75– 78.Crossref, Google Scholar

de Beurs, E., van Balkom, A. J., Lange, A., et al (1995) Treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia: comparison of fluvoxamine, placebo, and psychological panic management combined with exposure and of exposure in vivo alone. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 683– 691.Crossref, Google Scholar

Fahy, T. J., O'Rourke, D., Brophy, J., et al (1992) The Galway Study of Panic Disorder I. Clomipramine and lofepramine in DSM–III–R panic disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 25, 63– 75.Crossref, Google Scholar

Fava, G. A., Savron, G., Zielezny, M., et al (1997) Overcoming resistance to exposure in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 95, 306– 312.Crossref, Google Scholar

Fava, G. A., Rafanelli, C., Grandi, S., et al (2001) Long-term outcome of panic disorder with agoraphobia treated by exposure. Psychological Medicine, 31, 891– 898.Crossref, Google Scholar

Foa, E. B., Franklin, M. E. & Moser, J. (2002) Context in the clinic: how well do cognitive-behavioral therapies and medications work in combination? Biological Psychiatry, 52, 987– 997.Crossref, Google Scholar

Furukawa, T. A., Guyatt, G. H. & Griffith, L. E. (2002) Can we individualize the ‘number needed to treat’? An empirical study of summary effect measures in meta-analyses. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 72– 76.Crossref, Google Scholar

Gould, R. A., Otto, M. W. & Pollack, M. H. (1995) A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 15, 819– 844.Crossref, Google Scholar

Guy, W. (1976) ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville. MD: US Department of Health and Human Services.Google Scholar

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., et al (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327, 557– 560.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hollon, S. D. & DeRubels, R. J. (1981) Placebo–psychotherapy combinations: inappropriate representations of psychotherapy in drug–psychotherapy comparative trials. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 467– 477.Crossref, Google Scholar

Johnston, D. G., Troyer, I. E., Whitsett, S. F., et al (1995) Clomipramine treatment and behaviour therapy with agoraphobic women. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 192– 199.Crossref, Google Scholar

Kampman, M., Keijsers, G. P., Hoogduin, C. A., et al (2002) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive–behavioral therapy alone. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63, 772– 777.Crossref, Google Scholar

Loerch, B., Graf-Morgenstern, M., Hautzinger, M., et al (1999) Randomised placebo-controlled trial of moclobernide, cognitive-behavioural therapy and their combination in panic disorder with agoraphobia. British Journal of Psychiatry 174, 205– 212.Crossref, Google Scholar

Marks, I. M. & Mathews, A. M. (1979) Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behavior Research and Therapy. 17, 263– 267.Crossref, Google Scholar

Marks, I. M., Gray, S., Cohen, D., et al (1983) Imipramine and brief therapists-aided exposure in agoraphobics having self-exposure homework. Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 153– 162.Crossref, Google Scholar

Marshall, M., Lockwood, A., Bradley, C., et al (2000) Unpublished rating scales: a major source of bias in randomised controlled trials of treatments for schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 249– 252.Crossref, Google Scholar

Mattick, R. P., Andrews, G., Hadzl-Pavlovlc, D., et al (1990) Treatment of panic and agoraphobia. An integrative review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 178, 567– 576.Crossref, Google Scholar

Mavissakalian, M. & Michelson, L. (1986) Agoraphobia: relative and combined effectiveness of therapist-assisted in vivo exposure and imipramine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 47, 117– 122.Google Scholar

Mavissakalian, M. R. & Perel, J. M. (2002) Duration of imipramine therapy and relapse in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22, 294– 299.Crossref, Google Scholar

Mavissakalian, M., Michelson, L. & Dealy, R. S. (1983) Pharmacological treatment of agoraphobia: imipramine versus imipramine with programmed practice. British Journal of Psychiatry. 143, 348– 355.Crossref, Google Scholar

Nathan, P. E. & Gorman, J. M. (2002) A Guide to Treatments That Work (2nd edn). New York: Oxford University Press.Google Scholar

Oehrberg, S., Christlansen, P. E., Behnke, K., et al (1995) Paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 374– 379.Crossref, Google Scholar

Otto, M. W., Pollack, M. H. & Makl, K. M. (2000) Empirically supported treatments for panic disorder: costs, benefits and stepped care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 556– 563.Crossref, Google Scholar

Schmidt, N. B., Koselka, M. & Woolaway-Bickel, K. (2001) Combined treatments for phobic anxiety disorders. In Combined Treatments for Mental Disorders (eds M. T. Sammons & N. B. Schmidt). pp. 81– 110. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.Google Scholar

Sharp, D. M., Power, K. G., Simpson, R. J., et al (1996) Fluvoxamine, placebo, and cognitive–behaviour therapy used alone and in combination in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 10, 219– 242.Crossref, Google Scholar

Shear, M. K., Brown, T. A., Barlow, D. H., et al (1997) Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1571– 1575.Crossref, Google Scholar

Sheehan, D. V., Ballenger, J. & Jacobsen, G. (1980) Treatment of endogenous anxiety with phobic, hysterical and hypochondriacal symptoms. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37, 51– 59.Crossref, Google Scholar

Simon, N. M., Safren, S. A., Otto, M. W., et al (2002) Longitudinal outcome with pharmacotherapy in a naturalistic study of panic disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 69, 201– 208.Crossref, Google Scholar

Song, F., Altman, D. G., Glenny, A. M., et al (2003) Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ, 326, 472– 476.Crossref, Google Scholar

Spinhoven, P., Onstein, E. J. Klinkhamer, R. A., et al (1996) Panic management, trazodone and a combination of both in the treatment of panic disorder: Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 3, 86– 92.Crossref, Google Scholar

Stein, M. B., Ron Norton, G., Walker, J. R., et al (2000) Do selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors enhance the efficacy of very brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder? A pilot study. Psychiatry Research, 94, 191– 200.Crossref, Google Scholar

Taylor, S. (2000) Understanding and Treating Panic Disorder. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.Google Scholar

Telch, M. J., Agras, W. S., Taylor, C. B., et al (1985) Combined pharmacological and behavioral treatment for agoraphobia. Behavior Research and Therapy, 23, 325– 335.Crossref, Google Scholar

Thompson, S. G. & Sharp, S. J. (1999) Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Statistics in Medicine, 18, 2693– 2708.Crossref, Google Scholar

van Balkom, A. J., Bakker, A., Spinhoven, P., et al (1997) A meta-analysis of the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a comparison of psychopharmacological, cognitive–behavioral and combination treatments. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185, 510– 516.Crossref, Google Scholar

Wiberg, I. M. & Dahl A. A. (1996) Does brief dynamic psychotherapy reduce the relapse rate of panic disorder? Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 689– 694.Crossref, Google Scholar

Zitrin, C. M., Klein, D. F. & Woerner, M. G. (1980) Treatment of agoraphobia with group exposure in vivo and imipramine. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37, 63– 72.Crossref, Google Scholar

Zitrin, C. M., Klein, D. F., Woerner, M. G., et al (1983) Treatment of phobias. I. Comparison of imipramine hydrochloride and placebo. Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 125– 138.Crossref, Google Scholar